| Pictures, Images and Deep Reading

Janice Bland |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This paper considers the support provided by multimodal children’s literature in the development of literacy. The focus is on reading in a second language and the negotiation of understanding due to information gaps in the narrative, and on reading pleasure due to sensory anchoring through pictures. The development of deep reading is differentiated from the acquisition of functional literacy skills. Further, the differentiation between the medium-embeddedness of pictures and the perceptual-transactional and culturally shaped nature of images is highlighted with regard to the affordances of pictures in picturebooks and graphic novels. In some children’s literature, the opportunities for meaningful booktalk are amplified by an apparently simple style of illustration. This process has been termed amplification through simplification, which, in contrast to simplifying by stereotyping, can help lead to intercultural understanding and deep reading. The affordances of pictures in supporting young adult readers to create a mental model of a storyworld is discussed with reference to two panels from Coraline (Gaiman & Russell, 2008), a graphic novel.

Key words: deep reading, pleasure of literature, mental model, storyworld, amplification through simplification, cartoon style, picturebooks, graphic novels

Janice Bland (PhD) is Deputy Chair of TEFL at the University of Münster. She is author of Children’s Literature and Learner Empowerment. Children and Teenagers in English Language Education (2013) and volume editor of Teaching English to Young Learners. Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 Year Olds (2015), both Bloomsbury Academic. Janice is co-editor of CLELEjournal: Children’s Literature in English Language Education. [End of Page 24]

Introduction

Children’s literature is frequently illustrated, and the illustrations have a deep significance – for first language (L1) and second language (L2) pre-literate children, novice readers and also confident readers. In this paper I will look at an aspect of this significance related to deep reading. It is often pointed out that pre-literate children acquire their first literacy skills by reading pictures. Clearly the sensory anchoring supplied through the pictures in children’s literature constitutes one of the most supportive features for comprehension of the text: the illustrations simplify the understanding of the verbal text both for L1 and L2 readers. This is the case for example in picturebooks, illustrated chapter books – the term used for authentic children’s books with very short chapters ‘for children who have mastered basic reading skills but still require simple, illustrated texts’ (Agnew, 2001, p. 139) and graphic novels for young adults. This supports and motivates young L1 readers of the text and listeners to the read-aloud, and supports L2 readers in ways that are parallel, but not identical.

Negotiation of understanding

The pictures can provide a narrative scaffold to help the reader follow the story even when their linguistic competence is still limited. Consequently pictures often provide a meaning-anchor effect that supports inexperienced L1 readers, young language learners as well as teenage L2 learners. Multimodal texts, which contribute to the narrative in multiple modes – such as the pictures, the words, the design and peritext of picturebooks – do not however reiterate identical messages in each mode. The messages may overlap, complement, amplify or contradict each other; they may tell different stories from differing perspectives or even from different time periods. It is therefore frequently suggested that multimodal texts such as picturebooks and graphic novels provide rich opportunities for negotiation of understanding and meaning in second and foreign language education (see recent publications: Bland, 2013, chapters 2, 3, 4 & 7; Burwitz-Melzer, 2013; Hempel 2015; Lazar, 2015; Ludwig & Pointer, 2013; Ludwig, 2015; Mourão, 2013; Mourão, 2015, as well over half the articles in the first five issues of Children’s Literature and English Language Education ejournal, 2013-2015). [End of Page 25]

Sensory-anchored response

Pictures also motivate L1 and L2 readers by inviting personal engagement and a sensory-anchored response to the narrative. Pictures may, for example, trigger an affective response of pleasure, displeasure, tension, relaxation or excitement; or the response could be an emotional one of anger, fear, jealousy, pride or even love. Such engaged responses to narrative are an important aspect of the pleasure of literature. This pleasure is, of course, available to more mature readers through the verbal text alone; fluent readers have the ability to turn verbal imagery into mental images when

- they have a sufficiently developed mental lexicon and mental grammar to linguistically comprehend the text,

- they are practised in reading literature and transforming language into mental imagery,

- they have the world or cultural knowledge (schemata) to create a mental model of the storyworld.

These conditions are clearly more difficult to fulfil in L2 than in L1.

Deep reading

The ability to turn words into mental images distinguishes deep reading with understanding and pleasure from merely decoding words on the page, and this distinction is relevant for both L1 and L2 education. Children’s literature scholar Maria Nikolajeva (2014) highlights the chasm of understanding with regard to what constitutes ‘reading’. When educationalists (and politicians) focus on the primary school, there is usually heightened attention on acquiring basic skills, or functional literacy, but generally less attention on the learning processes of engaging insightfully with literary texts. With regard to foreign language education in the lower secondary school, attention to literary literacy and the development of deep reading is usually entirely disregarded. Nikolajeva (2014, p.1) refers to

the radical difference between reading skills and reading as an intellectual and aesthetic activity: deep reading. Being able to read is not the same as reading, [End of Page 26] which we see from numerous alarming reports from countries with high levels of literacy, but rapidly decreasing levels of reading.

This is counterproductive, for narratives are an important pedagogic medium; they support humankind’s drive to construct coherence and meaning and they can take the reader on educational journeys (Bland, 2015; Boyd, 2009). Thus children’s literature, ‘an umbrella term that is usually considered by scholars to include young adult literature, oral literature, film, digital media and visual texts for young people’ (Bland, Lütge & Mourão, 2015, p.ii), is pedagogically pivotal. Waiting until learners in the school context are old enough for adult literature must surely create a rupture in students’ literacy development that may be difficult to reverse, and short excerpts from literary texts, for example in EFL textbooks, cannot provide complex educational journeys.

One way that high quality children’s literature can afford a shortcut to the development of deep and pleasurable reading is through the scaffolding of pictures.

Pictures as a Shortcut to Deep Reading

Pictures and images

The pictures, although they carry meaning in a highly accessible way, also demand participation. Hans Belting differentiates pictures, carried by a medium such as a book or canvas, from images as follows: ‘Images are neither on the wall (or on the screen) nor in the head alone. They do not exist by themselves, but they happen; they take place whether they are moving images (where this is obvious) or not’ (Belting, 2005, p. 302, emphasis in the original). Our individual response to pictures, guided by the archive of images in our memory, which rests on personal experience, affords countless opportunities for dialogic negotiation of understanding as well as creative writing tasks in the L2 classroom. For example, many children can call up an image of a character that can fly, such as Peter Pan, a wicked witch or Harry Potter on his broomstick. These images will help them engage creatively – creating a mental model – with intertextually related pictures they encounter, and later – as practised deep readers – with purely verbal text. [End of Page 27]

Creating a full mental model of the storyworld is prohibitive when younger readers are required to read simplified adult texts, which typically allude to adult schemata, for an archive of images based on personal experience is missing. However, even in the case of adult texts, pictures will help the L2 reader fully comprehend the storyworld and its cultural connotations. For example The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini’s Bildungsroman, has been remediated as a graphic novel (Hosseini, Andolfo & Celoni, 2011), and is therefore now accessible to a mid-secondary-school readership. The accessibility is enhanced through the panels of the graphic novel not only because the pictures share in the storytelling, but also and particularly because they vividly and authentically elucidate the cultural context.

Access to cultural context through pictures

The pictures in children’s literature frequently provide easier access to cultural background in the sense that they are physically present and frozen in time, however this does not diminish their educational potential, but rather extends it. Dolan (2014, p. 92) calls picturebooks ‘windows and mirrors’ and ‘a powerful vehicle in the classroom in terms of intercultural education for all learners, including those working through the medium of a second language’. The pictures in children’s literature are windows in that the student can see into another world, and mirrors in that the different world reflects back a reality that allows the reader to see their own world in a new light. Authentic picturebooks and graphic novels reflecting cultural diversity thus move readers towards flexibility of perspective – away from rather monolithic, and in L2 textbooks, often stereotyped input on other cultures towards intercultural competence. Simplified and stereotyped pictures do not necessarily support communication but are likely to devalue it, by diminishing the transactional affordance of pictures – the negotiation of understanding and meaning – and by distorting the access to the cultural memory of another speech community.

Amplification through simplification

A cartoony or stylised artistic style, common in comics and graphic novels, is not the same as the stereotyped, fossilized pictures often encountered in graded readers and L2 textbooks. When Scott McCloud identifies ‘amplification through simplification’, he refers [End of Page 28] to an abstract and therefore potentially more universal cartoon style, which can be more focused and intense than realistic styles (McCloud, 1993, p. 30). It can also offer wide opportunities for negotiation of understanding and meaning, as the meaning is less defined. Amplification through simplification was a literary technique already before the advent of the graphic novel medium. It is used to stunning effect in George Orwell’s allegorical Animal Farm (1945), for example.

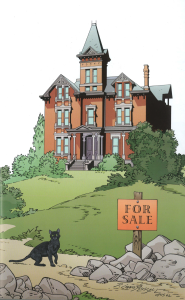

Figure 1. FOR SALE from Coraline by Neil Gaiman © (2002, 2008), illustrated by Craig Russell © (2008). Used by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. [End of Page 29]

Supporting Deep Reading with Pictures: An Example

Neil Gaiman’s graphic novel Coraline (2008) illustrated by Craig Russell, is adapted from Gaiman’s prize-winning young adult novel Coraline (2002). It is helpful for the L2 student to explore ideas for film analysis and the understanding of movie techniques initially with the still pictures of graphic novels,

while movies offer a stream of images and thus require a reconstruction of particular scenes in the discussion, the panels of comics can be analysed more easily as they are fixed on the page and it is always possible to return to earlier pictures if this should be necessary. (Vanderbeke, 2006, p. 368)

I suggest the very first illustration in Coraline (see Figure 1) is a striking example of amplification through simplification; while deceptively simple, it invites the reader to interact with the forthcoming story – helping to initiate a mental model of the storyworld from the outset. Craig Russell’s simplified outline of the lonely house, which plays a central role in the narrative, in flat pastel colours, suggests this grand old house symbolizes something beyond itself, as if it were alive. The capitalized ‘FOR SALE’ sign, set among uninviting grey rocks in the foreground, points to an ominously unknowable adventure. The new home of the protagonist Coraline, the apartment she moves into with her parents and the grand old house itself, will play a major role in the story.

The watchful black cat in the foreground is poised ready to run away, suggesting danger and possibly magic. The cat watches the reader, a gaze that constitutes a demand image (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006, pp. 116-124). The demand in this case seems to be either a warning to stay away or an enticement to the reader to dare to enter the storyworld. Teen readers are able to recognize certain conventions from their horror-narrative schema, for horror is a popular genre amongst many girls as well as boys. Typically young adult readers point to the connection between a black cat and witches, the spooky atmosphere of an old house standing isolated on a hilltop, the towering roof and chimney, the secretive and blind appearance of the tall, narrow windows and one side of the house shrouded in darkness, helping them to predict significant elements of the story. It is interesting to discuss in a class with teen readers how pictures (as well as verbal text) create meanings [End of Page 30] for readers to interpret. Images, in the perceptual-transactional, taking-place sense described above, may have belonged to the collective imagination for as long as humankind has told stories:

Images may be old even when they resurface in new media. […] The media are usually expected to be new, while images keep their life when they are old and when they return in the midst of new media. […] Images resemble nomads in the sense that they take residence in one medium after another.’ (Belting, 2005, p. 310)

However, the conventional and culturally widely shared image of ‘home’ in children’s literature, as a place of calm and safety as opposed to the excitement and danger of ‘away’ (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, p. 199), is interrogated in Coraline, as is suggested in this initial full-page panel. Welcoming details are missing: there are no flowers in the garden, no indications of human life and habitation. Readers, at approximately the age of Coraline, around 13 years old, have a great deal of experience in reading pictures, and may notice more than the teacher. Nonetheless, it is productive for L2 students to work initially in groups around pictures to negotiate understanding and meaning without the risk of losing face, just as for verbal texts: ‘Reading activities built up around motivating, challenging comprehension tasks that have to be performed in small groups create the intimacy condition required for many learners to signal their incomprehension to each other and to negotiate meaning’ (Van den Branden, 2008, p. 166).

At a later stage in the graphic novel, Coraline discovers there is a parallel world, created by an eerie ‘other mother’, hidden within and around the house. When walking through the garden of the ‘other world’ (see Figure 2), Coraline discovers that the further she walks the less real it becomes: ‘the trees becoming cruder the further you went. Pretty soon they seemed very approximate, like the idea of trees’ (Gaiman & Russell, 2008, p. 82). The original young adult novel text is only slightly longer: ‘the trees becoming cruder and less treelike the further you went. Pretty soon they seemed very approximate, like the idea of trees: a greyish-brown trunk below, a greenish splodge of something that might have been leaves above’ (Gaiman, 2002, p. 86). [End of Page 31]

Figure 2. Page 82 from Coraline by Neil Gaiman © (2002, 2008), illustrated by Craig Russell © (2008). Used by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

The pictures not only carry the meanings lost by the slight shortening of the text, they further augment the opportunities for negotiation of understanding and meaning. Creating this scene in pictures, Russell uses the layout to slow down the narrative, by spreading two large panels right across the page. He draws attention to his extremely cartoon-like style in representing the unreal other world, which becomes sketchier and sketchier. Coraline appears to walk out of each panel, almost to drop out of the world. Russell has with his art and salience on the cruder and cruder trees recreated the ‘invented’ nature of the other world, thus he draws attention to the means of creating a graphic novel – his art. In the first [End of Page 32] panel, where the trees are crudest, typographic experimentation is also employed. This suggests that not only the other mother’s world is a fiction, but also the narration (which of course it is).

This slippage between the mode of writing and the mode of pictures creates metafiction or self-reflexivity, and is a common device in postmodern fiction, picturebooks and graphic novels. Self-reflexivity helps readers consider how texts are constructed, and illustrates how pictures in some children’s literature, as well as in much modern media, are becoming more abstract and symbolic, in a parallel development to how ‘written communication necessarily has become concise and abstract over generations and across the distances between agricultural and industrial communities’ (op de Beeck, 2011, p. 118).

Conclusion

Pictures in children’s literature do much more than aid comprehension and provide easy access to literary texts, important though this is. Although a number of research publications have appeared in recent years on the use of picturebooks and graphic novels in language education (see introduction), there is still much misunderstanding as to the educational value of picturebooks and graphic novels, particularly in EFL contexts. This is surprising considering the steadily lowering of the age of language learners. In addition to the scaffolding nature of pictures, I suggest the differentiation between the medium-embeddedness of pictures and the perceptual-transactional and culturally shaped nature of images highlights the affordances of pictures for negotiation of understanding and for an all-important introduction to deep reading.

Picturebooks and graphic novels have developed in complexity and quality relatively recently, yet they overlap, gain from and intertextually refer to older media. The postmodern fluidity of literary texts has a number of precedents: ‘Old media do not necessarily disappear forever but, rather, change their meaning and role. […] Painting lived on in photography, movies did in TV, and TV does in what we call new media…’ (Belting, 2005, p. 314, emphasis in the original). Allowing award-winning picturebooks and graphic novels to introduce pleasurable reading to readers not yet ready for adult literary texts – which as I have shown is not only a matter of linguistic difficulty – can only [End of Page 33] aid the fight against decreasing levels of reading and prepare for deep reading. For as Roderick McGillis writes:

Children’s literature is not hermetically sealed from either other literature or from the field of cultural production generally. The possibilities for interpretation of this literature are as varied as they are for any literature. This is an important lesson because many books for the young are disarming in their ostensible simplicity. Theory has taught us that what appears simple does so because we have not looked closely enough at that simple thing. (McGillis, 2010, p. 14)

Bibliography

Gaiman, N., illus. McKean, D. (2002), Coraline. New York: HarperTrophy.

Gaiman, N., illus. Russell, C. (2008), Coraline Graphic Novel. New York: HarperCollins.

Hosseini, K., illus. Andolfo, M. & Celoni, F. (2011), The Kite Runner. Graphic Novel. London: Bloomsbury.

References

Agnew, K. (2001). Chapter books. In V. Watson (Ed.), The Cambridge Guide to Children’s Books in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 139.

Bland, J. (2013). Children’s Literature and Learner Empowerment. Children and Teenagers in English Language Education. London: Bloomsbury.

Bland, J. (2015). Oral storytelling in the primary English classroom. In J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners. Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 year olds. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 183-198.

Bland, J., Lütge, C. & Mourão, S. (2015). Editorial. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 3(1), ii-iii.

Boyd, B. (2009). On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [End of Page 35]

Burwitz-Melzer, E. (2013). Approaching literary and language competence: Picturebooks and graphic novels in the EFL classroom. In J. Bland & C. Lütge (Eds), Children’s Literature in Second Language Education. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 55-70.

Dolan, A. (2014). Intercultural Education, Picturebooks and Refugees: Approaches for Language Teachers. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2(1), 92-110.

Hempel, M. (2015). A picture (book) is worth a thousand words: Picture books in the EFL primary classroom. In W. Delanoy, M. Eisenmann & F. Matz (Eds), Learning with Literature in the EFL Classroom. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 69-84.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2006), Reading Images: the Grammar of Visual Design (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Lazar, G. (2015). Playing with words and pictures: Using post-modernist picture books as a resource with teenage and adult language learners. In M. Teranishi, Y. Saito & K. Wales (Eds), Literature and Language Learning in the EFL Classroom. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ludwig, C. (2015). Narrating the ‘Truth’: Using autographics in the EFL classroom. In W. Delanoy, M. Eisenmann & F. Matz (Eds), Learning with Literature in the EFL Classroom. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 299-320.

Ludwig, C. & Pointner, F. (2013). Teaching Comics in the Foreign Language Classroom. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding Comics. The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins.

McGillis, R. (2010). ‘Criticism is the Theory of Literature’: Theory is the Criticism of Literature. In D. Rudd (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Children’s Literature. London: Routledge, pp. 14-25.

Mourão, S. (2013). Picturebook: Object of discovery. In J. Bland & C. Lütge (Eds), Children’s Literature in Second Language Education. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 71-84.

Mourão, S. (2015). The potential of picturebooks with young learners. In J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners. Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 year olds. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 199-217.

Nikolajeva, M. (2014). Reading for Learning. Cognitive approaches to children’s literature. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Nodelman, P. & Reimer, M. (2003). The Pleasures of Children’s Literature (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Op de Beeck, N. (2011). Image. In P. Nel & L. Paul (Eds), Keywords for Children’s Literature. New York: New York University Press, pp. 116-120.

Van den Branden, K. (2008). Negotiation of meaning in the classroom. Does it enhance reading comprehension? In A. Mackey, R. Oliver & J. Philp (Eds), Second Language Acquisition and the Younger Learner. Child’s Play? Amsterdam: John Benjamin, pp. 149-169.

Vanderbeke, D. (2006). Comics and graphic novels in the classroom. In W. Delanoy & L. Volkmann (Eds), Cultural Studies in the EFL Classroom. Heidelberg: Winter, pp. 365-375. [End of Page 36]