| Storytelling Projects on Native American Children’s Literature for Primary English Education: A Case Study

Dolores Miralles-Alberola |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This article describes the experience of a storytelling project undertaken at the University of Alicante (Spain) in a course entitled ‘Didactics of English Language’, followed as part of a BA degree in Primary Education (for students 6–12 years old). The storytelling project was designed by the author of this article and involved student teachers who developed an innovative design integrating Native American children’s and young adult literature by authors Joy Harjo, Luci Tapahonso, Simon Ortiz, Michael Caduto and Joseph Bruchac, among others. This pedagogic experiment gave student teachers the opportunity to discover unfamiliar texts and to explore such texts in the spirit of critical literacy and intercultural citizenship, and to select the necessary tools to develop course syllabi.

Keywords: Native American children’s literature, critical literacy, intercultural citizenship, compelling reading, English language education, project-work learning

Dolores Miralles-Alberola (PhD) teaches in the English Department of Language and Literature Education, University of Valencia in Spain. She received her PhD in Latin American Literature with a Designated Emphasis in Native American Studies from the University of California, Davis. She has published diverse academic articles on resistance literature, film, and English language education.

Introduction

More than ever, intercultural practices are vital to the current educational debate in Spain, following the demands of the new Education Law that came into force in January 2021. The national curriculum is currently being developed in concert with the autonomous communities (the political and administrative regions in Spain with local governments that have a limited autonomy in aspects such as the implementation of the education curriculum based on the national educational law). Although previous laws considered the importance of competences, in the LOMLOE (Organic Law Amending the Organic Law of Education), key competences rather than content are now the main focus. The new law states that children’s rights must be at the heart of the curriculum, along with gender equality, sustainability, and global citizenship. Out of the eight key competences mentioned in the law, which are based on the Council of the European Union (2018) recommendation on key competences for lifelong learning, two are intrinsically related with education in intercultural citizenship: Citizenship Competence and Cultural Awareness and Expression Competence. The first refers to the development of responsible and civic social participation, the fostering of world citizenship and the commitment to sustainability; the second aims at a critical, positive and respectful attitude towards cultural differences.

Given literature’s role in representing specific cultural identities, the use of appropriate literary texts in language education is warranted. Furthermore, the teaching of a second language through the playful and critical use of literary texts has proven to be beneficial and has made a comeback in recent years (Bland, 2013, 2018; Hall, 2015), after communicative language teaching ‘re-positioned’ literature to a secondary role (Hall, 2015, p. 19). This article analyses the results of the final projects created by pre-service student teachers in a course entitled ‘Didactics of English Language for Primary Education’ taught at the Faculty of Education of the University of Alicante, Spain, in the academic year 2020-2021. Projects were based on books under the generic label of Native American children’s and young adult literature, written by well-known Indigenous authors from Canada and the United States. The objective of the projects was not only for student teachers to develop activities that they might apply as teachers, but also to make them aware of these different traditions and the relevance of cultural contexts in the classroom.[i]

Native American literature has been an integral part of North American literary history in English since the earliest testimonial writings in English written in the 17th century. It was only after Scott Momaday was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1969, however, that it became one of the most acclaimed literary traditions in the United States and Canada (Allen, 1983; Deloria, 1994/1972; Owens, 1998/2001; Rainwater, 1999; Weaver, 1998). Native American literature aimed at children and young adult audiences is more recent. Often based on Native oral traditions, it can be found in a variety of formats including picturebooks, poetry, and memoirs, among others. Although Indigenous children’s literature in English is receiving ample critical attention in the context of the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand, it should be noted that there are not many studies on the use of Indigenous children’s literature in English language teaching. For this reason, along with other secondary sources such as American Indians in Children’s Literature, a well-established blog written since 2006 by Debbie Reese of Nambé Pueblo (https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/) and Cynsations, a website coordinated by Muscogee writer Cynthia Leitich Smith (https://cynthialeitichsmith.com/cynsations/), I assigned my own chapter entitled ‘Native American Children’s Literature in the English Language Education Classroom’ (Miralles-Alberola, 2021a) as a secondary source, as it offers a theoretical framework on Native American children’s literature and its affordances in English language education, as well as reviews of the books used in the projects.

Selection Criteria

In a study with a more ample selection of intercultural literature I am currently carrying out, student teachers answered a question – before taking any action – about the type of literature that would be appropriate to use in the English classroom. Out of 63 individuals, many responded (some in Catalan): dynamic, amena (entertaining), fun, traditional literature such as the Ghost of Christmas Past (referring to A Christmas Carol), Harry Potter, comic adaptations, literature relevant to today’s world, genres and formats children have never read, Geronimo Stilton, The Little Prince, Disney books, plays and poetry. Some talked about ‘universal literature’, which some years ago served to refer to non-Spanish literature, suggesting titles or protagonists such as Sinbad, Gulliver, William Tell, The Pied Piper of Hamelin, The Odyssey, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Jungle Book, or A Journey to the Centre of the Earth, all of them in adapted versions. However, only a few referred to world literature or children’s literature that promotes interculturality and basic social rights. It appears to be important to widen the information about more challenging books and provide a glimpse of intercultural literature, opening the current canon of the books used in English language education with student teachers in the Spanish context.

We selected the course literature based on group questionnaires. Because the pedagogical use of Native American literature has scarcely been explored in the Spanish educational context, I had to make sure that the activities created by the student teachers for this small research project remained respectful of the source culture (Slapin et al., 2000), and avoided stereotyping. On the other hand, I had to include works that were likely to create fascination in readers (Krashen & Bland, 2014). Oyate, based in Berkeley, California, is a Native organization that published the guide How to Tell the Difference: a Guide to Evaluating Children’s Books for Anti-Indian Bias. In the guide, they refer to themselves as ‘working to see that our lives and histories are portrayed honestly and so that people will know our stories belong to us,’ and provide guidance about the representation of Native peoples, appealing to truthfulness and respect. The guide revolves around the sensitization towards stereotypes, and poses the question ‘Is there anything in this book that would embarrass or hurt a Native child?’ to ensure that no child should ever be hurt when their culture is represented in any type of literary artifact. Other aspects to consider according to the guide are tokenism, loaded words, distortion of history, standards of success, role of women and elders, and background of authors and illustrators (Slapin et al., 2000).

As Indigenous scholars claim, it is important to pay attention to the background of authors, since Native Americans have been depicted by non-Natives for quite a long time, providing the audience with the fake feeling of being sufficiently informed. Yet who gets to tell the stories is a vital matter (Cook-Lynn, 1996; Deloria, 1972/1994). We must ponder whether the authors are qualified or not to write about Native peoples in an accurate and respectful manner in order to avoid ethnocentric bias (Slapin et al., 2000, p. 25), or disastrous consequences such as the incorporation of the hoax novel The Education of Little Tree in the syllabus of some educational programmes in schools, colleges and universities (Roche, 1999, pp. 269-71). Nambé Pueblo scholar Reese (2018) demands that teachers choose books written by Native writers to overcome representations of Native peoples as ‘primitive and uncivilized’ (p. 389). What is more, tribally specific books will help to inform about diverse realities regarding governance, languages, spirituality and stories as a way to avoid stereotyping Indigenousness (pp. 389-91).

Critical literacy was developed within the critical pedagogy promoted by Paulo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970/2005) as a perspective that teaches how to read critically in order to contribute to the development of curiosity and critical reflection, as well as the recognition of conformity to the dominant culture and power structures. Hilary Janks (2013) points out how ‘critical literacy is about enabling young people to read both the world and the word in relation to power, identity, difference and access to knowledge, skills, tools and resources’ (p. 227, italics in original). Literary languages and art are susceptible to bias, as every text is ideologically laden, so it makes perfect sense, when it comes to the selection of materials, to include as many experiences from different nationalities, ethnicities and social backgrounds in language teaching as possible, so that none in particular is hegemonic (Bland, 2018, p. 3). Reese (2013, 2018), on her part, expands the concept to critical Indigenous literacies, highlighting the importance of encouraging ‘children to read between the lines and ask questions when engaging within literature: Whose story is it? Who benefits from these stories? Whose voices are not being heard?’ (2018, p. 390). It should be added that this is thinking about Indigenous children reading within their own cultures, but also non-Indigenous children entering into the stories from and about Native cultures, as ‘the larger culture needs to unlearn and rethink how the identities of Indigenous peoples are represented and taught (Reese, 2018, p. 390).

Also crucial for the selection criteria is the captivation factor. The ‘compelling comprehensible input’, derived from the input hypothesis coined by Stephen Krashen (1982/2009, pp. 7-9), states that comprehension is crucial for learning a second language, as we acquire more competence the more we are exposed to comprehensible input. Based on further research, Krashen and Bland (2014) go further by expanding the term to ‘compelling comprehensible input’ to describe the engaging readings that contribute to the desire to learn a language in order to access such information, readings that, for one reason or another, captivate a certain type of reader. Fascination with reading is said to entail three phases, the first being oral, based on the stories heard (and seen, as in the case of films), whereas the second phase would consist of the self-selection of captivating texts by readers and, finally, the third would refer to academic or specialized reading (Krashen & Bland, 2014). For this reason, in order to provide critical access to the ideal of academic language, it is necessary to create readers from the first moments of access to reading, with an ample selection of genres, topics, authors from different backgrounds and stories from different contexts that provide a variety of points of view and have the ability to appeal to the widest possible audience.

Books Selected for the Projects

The books used for this research were selected from the area of Native American literature for children and young adults, and have been requested through the Acquisitions Service of the University of Alicante, more specifically, the library of the Faculty of Education, over a period of about three years. Without their collaboration it would have been impossible to gather the works that are part of the study. The library also worked diligently in the distribution of the books to the students, taking into account the limitations of access due to Covid-19. As they were published by small companies overseas, many of the pieces were difficult to obtain due to small print runs or problems of distribution, despite being works written by popular authors. A curious fact to exemplify this: it was impossible to buy one of the central texts, How to Tell the Difference: a Guide to Evaluating Children’s Books for Anti-Indian Bias, even after talking directly to Oyate, the organization in Berkeley. The only way we could get hold of it was through interlibrary loan, and amazingly it was only allowed for one week, after having crossed the Atlantic. This is evidence of how important the work of librarians is in order to provide access to books that belong to literatures and traditions that otherwise would be out of reach, not only for the general public, but also for scholars and instructors.

The works, which will be approached in the paragraphs below, are the following:

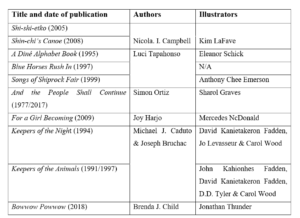

Table 1. Children’s books included in the study

Shi-shi-etko (2005) and its continuation, Shin-chi’s Canoe (2008), are picturebooks by Nicola Campbell, a Métis/Interior Salish author, of the Canada First Nations. Shi-shi-etko and her brother Shin-chi’s stories are examples of the Indigenous children that were separated from their parents and communities by the Canadian Government and placed in religious Residential Schools. There they were stripped of their languages, traditions and dignity, sometimes abused and gone missing, never returning to their families. These abhorrent practices took place also in the United States, from the beginning of the 19th century until the 1970s (Miralles-Alberola, 2021a, pp. 126-27). Shi-shi-etko narrates the last days the little girl spends with her family and her community, whereas in Shin-chi’s Canoe, which is set one year later, it is Shi-shi-etko’s brother’s turn to go to the Indian Residential School, accompanying his sister. This continuation also allows discussion of Shi-shi-etko’s grim experience during her first year. These works typically have a great impact on students, since they are tales of abduction, based on reality. However, Shi-shi-etko is told from the child’s perspective, in a non-violent gentle way, leaving the silences to the discretion of the reader to be completed. There is no rage in the way the little girl narrates the last days she spends with the members of her family right before setting off for the Government boarding school. One day, she paddles in the river with her father, the next, she bathes in the creek with her mother, and the last day before departure, while visiting the silver willow, her grandmother gives her a bag ‘made from soft, tanned deer hide and sinew’ (Campbell, 2005), in which to keep her family immaterial treasures. This bag metaphorically works as what Thomson (2002) terms a virtual school bag, serving as a place for children to keep what they know from home, from their communities (p. 1). Some children, though, are prevented from opening their school bags and sharing the contents with their peers (Bland, 2018, p. 6). This book teaches us about the pain children might go through when they are made to feel ashamed and fearful in places such as schools where they should be safe.

The works written by Luci Tapahonso, Diné writer and the inaugural Poet Laureate of the Navajo Nation (2013-2015), belong to different formats and age ranges. Navajo ABC. A Diné Alphabet Book is addressed to the first grades of Primary School (children 5–7-years-old) as a way to introduce the English alphabet and pronunciation, but can also serve to expand on concepts and items related to Navajo culture such as ‘hooghan’, ‘fry bread’, ‘loom’, etc. The picturebook Songs of Shiprock Fair describes a day in a fair with colourful pictures and musical words, and could be used as the central text for project-based learning, of which the final product or event would be to organize a fair in the classroom. Blue Horses Rush In is an excellent collection of poems and stories that are deeply connected to Native American literature and can be defined as memoir interwoven with the individual and kin, the self and the community, history and mythology (Miralles-Alberola, 2021a, p. 137). The collection merges different art manifestations such as poetry, photography, narrative, individual accounts and family memories, providing a format that can accommodate different sensitivities and different cultural backgrounds. Thus, Blue Horses Rush In can work as a mentor text for students to create their own memoirs – considering that mentor texts work as inspiration for creative writing (Bland, 2013, pp. 156-87).

Acoma Pueblo author Simon Ortiz’s And the People Shall Continue was originally published in 1977 and reprinted in 2017. This picturebook tells the history of the Americas from a Native perspective since pre-contact times, and provides an account about the arrival of the Vikings, the colonization by the Spaniards and other Europeans, the Gold Rush, the Reservations, and boarding schools, and culminates with encounters with other colonized impoverished peoples, as an empathy act, ‘in a land where they are identified as equal, and in a moment when stories must be shared’ (Miralles-Alberola, 2021a, p. 139). From a critical literacy perspective, And the People Shall Continue could be a good example of how 11–14-year-old students can do research to identify the different peoples described and the historical and social circumstances, while reflecting on a fragment on the last page:

We must fight against those forces

which will take our humanity from us.

We must ensure that life continues.

We must be responsible to that life.

With that humanity and the strength

which comes from our shared responsibility

for this life, the People shall continue.

For a Girl Becoming (2009), by the first Native American Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, of the Muskogee nation, is a picturebook presenting the connection of a young woman with her past, her community and her spiritual context. It can work as a mentor text not only for girls, but also boys. Male protagonists are traditionally more common in children’s stories, and – why not? – boys should also practice empathizing with female characters. This picturebook represents the narrative force women possess within many Indigenous traditions, where women are the heart of the literary impulse, the ones that name the world into being (Allen, 1992, p. 164). Bringing the perspective of Native American woman empowerment into the classroom would greatly help deconstruct some clichés which regard feminism as only a Western philosophy.

Keepers of the Night (1994) and Keepers of the Animals (1991/1997) by Michael Caduto and Joseph Bruchac are part of a series that started with Keepers of the Earth (1988) and Keepers of Life (1994). They are compilations of authentic oral stories articulated in complete Native-centred lesson plans that relate traditional tales with astronomy, biology, science, etc. The volumes are manuals divided into sections that normally include two traditional stories connected to activities of other disciplines. In Keepers of the Animals, suggested activities revolve around traditional stories ‘How Grandmother Spider Named the Clans’ (Hopi – Southwest) and ‘How the Spider Symbol Came to the People’ (Osage – Plains), giving them a geographical as well as a specific cultural context, acknowledging tribal diversity. Both stories are grouped under the concept of ‘Creation’ and, taking the stories as a starting point, the activities radiate into discussion questions, biology explanations and also games to perform in and out of the classroom.

The picturebook Bowwow Powwow (2018) is an Ojibwe-centred story written by Ojibwe scholar and author Brenda Child, illustrated by artist Jonathan Thunder, and translated into Ojibwe by Gordon Jourdain. All of the creators are Ojibwe, and the narration focuses on a powwow tribal festival, with the depiction of traditional dances with grass dancers and jingle-dress dancers. Special attention should be paid to the nature of the illustrations and their cinematic appearance, perhaps because Thunder is an animation artist, who points out: ‘When I was given the chance to make some concept art for the book, I went with a drawing that I considered to be both magical and luring to readers to want to see more’ (Leitich Smith, 2019).

The Study

Taking into account the difficulty of inclusion of texts foreign to the corpus of the Spanish educational system, this study tries to analyse the evolution of the pre-service student teacher’s perspective, once the texts have been worked on, based on the hypothesis that critical literacy, fascinating reading and the specificity of Native American children’s literature can have transformative potential. Thus, the main objectives of this study were:

- to foster critical literacy and intercultural citizenship among students through the recognition of other literatures and their application in primary school,

- to analyse the transformation of student teachers’ perspectives through their own work and research on Native American literatures,

- to contribute to creating a taste for compelling and transformative literature,

- to determine the feasibility of using Native American children’s literature as well as other minority literatures in the language classroom through the involvement of pre-service teachers (Miralles-Alberola, 2021b, p. 389).

Procedure

This study was developed as a ‘Storytelling Project’ in which student teachers plan an innovative design using a literary work as a unifying thread. In order to promote critical literacy and intercultural citizenship, such pre-selected works of Native American literature for children and young people were assigned to the different work groups that make up the study following a protocol (see under section ‘Phases’).

Participants

The students participating in this study were pre-service teachers in their first year of the Degree in Primary Education at the University of Alicante. However, a very low percentage of student teachers physically attended classes over the whole semester because classes during the month of February (the first weeks of the semester) were exclusively online due to Covid-19 restrictions at the Valencian Region public universities, and the rest of the semester classes were bimodal in shifts of 20% students in class.

As mentioned above, this educational experience focused on carrying out the compulsory task ‘Storytelling Project’, in which students worked in thirteen groups of four people and one group of three, making a total of 55 students in Group 2, out of nine groups with a total of 402 student teachers in the First Year of the Degree in Primary Education 2020-2021. Out of the 55 students, 43 are women and 12 are men. Most of them were 18 at the time of the study, although some were a little older.

Phases

The phases of the project correspond with the questionnaires the students had to complete for the research. First, students were informed about the nature and requirements of the assignment ‘Storytelling Project’ which was implemented for the first time during the academic year 2020-2021. In groups, students had to elaborate a project for the primary classroom with a work of Native American children’s literature as a unifying thread, which would be assigned by the teacher on the basis of the group answers to a first questionnaire. Subsequently, the students answered a pre-questionnaire and then a post-questionnaire with similar questions, in order to provide data to assess changes if any.

First questionnaire (completed 28 April 2020). Once the groups were formed, students completed a mandatory questionnaire about their preferences, which would serve to assign the different books to the groups. At this stage it was necessary to come to agreement about their choices. Before answering the questionnaire, student teachers had read Miralles-Alberola (2021a) in order to form an idea of the different titles available and to have a first contact with the various aspects to be taken into account when designing their projects. The chapter also provides a theoretical framework on Native American children’s literature, as well as on the application of this literature in the Spanish educational context, and some possibilities for activities and projects.

Second questionnaire (released 29 April 2020). The questions include whether student teachers would actually use this literature in class in the future, and how to improve the information and guidelines for the task ‘Storytelling Project’. The questionnaire also served as an in-process assessment of the assignment and remedial evaluation.

Third questionnaire (due after 26 May 2020). The items of the post-questionnaire were slightly different from the pre-questionnaire. Most of the questions were similar to those of the pre-questionnaire, but were formulated in the present perfect in order to account for any changes. Other questions were new, such as the last question asking students whether they would like to continue learning about Native American literature, or the open-ended questions referred to the skills or knowledge acquired for the project, if any, and the use of children’s Native American literature in primary school in Spain.

Results

The data analysis took into account the results obtained from the pre-questionnaires and comparing these with the results from the post-questionnaires. Planning the research with pre- and post-surveys facilitated an analysis of changes in attitudes of the participants in the study. I also carried out a qualitative analysis from the assessment of the projects presented in the course, in which the students demonstrated the implementation of the newly acquired tools and the application of the resulting knowledge and research.

In response to the question ‘How would you improve this práctica?’, some participants said that they would have preferred to work with a more well-known book, something more readily comprehensible, while others appreciated the opportunity to work with less common literature. Several respondents spoke of having more books available and more choices. In other cases, several asked for more context. These responses helped me to attend to the groups individually during the working process, to address their doubts and to provide additional materials and/or indicate where to look for them.

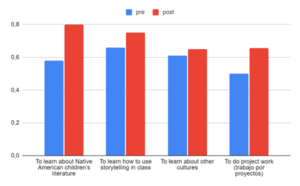

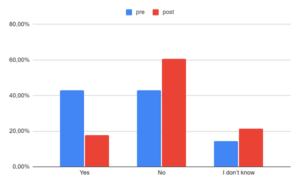

The answers to the question ‘What do you expect to acquire from this práctica?’ varied slightly from the pre- to the post-questionnaire, with a change of perspective towards willingness to learn more about Native American children’s literature (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Acquisition of knowledge/skills

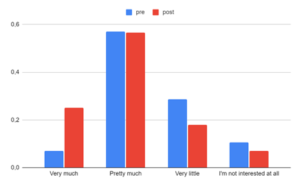

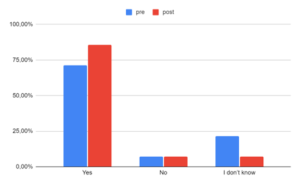

The responses to the other two questions about this topic, ‘How interested are you in Native American literature?’ (Figure 2) and ‘Do you think we should use Native American children’s literature in primary school in Spain?’ (Figure 3) also showed a positive increase regarding interest in Native American literature, so it can be inferred that both personal appreciation for this type of literature and student teachers’ opinions regarding the relevance of its use in the teaching of English in primary school in Spain have increased.

Figure 2. Interest in Native American Literature

Figure 3. Appropriateness of Native American Literature in English language education in Primary

The open-ended responses to ‘If the answer is yes, why?’ illustrate a depth that shows personal learning, reflection on one’s own experience, and empathy:

‘para que la asignatura de Inglés no se base únicamente en el lenguaje y se conozca la importancia de la cultura al igual que en otras asignaturas’ [so that English language classes would not be based entirely on language and the importance of culture is recognized, as it happens with other subjects]

‘porque así pueden aprender sobre otras culturas, sus costumbres y respetar a los demás’ [because in that way pupils can learn about other cultures, their customs and respect others]

‘because this can help the diversity in the world’

‘porque sirve para conocer otra cultura y creo que es algo que los niños y niñas les gustaría’ [because it can help to learn about another culture, and that’s something children might enjoy]

‘porque les puede ayudar a tener una visión más general de los diferentes tipos de literatura’ [because it can help pupils have a wider view about different types of literature]

‘considero que [sic] deberían de utilizar en las aulas de Primaria porque así se da visibilidad a todas aquellas culturas que fuera de Europa son desconocidas y en cambio son muy interesantes’ [I consider it should be used in the primary classrooms, that way it could give visibility to those cultures outside of Europe that are unknown but are very interesting]

‘es algo que normalmente no nos enseñan, y podría ser interesante. Yo en 5º o 6º de primaria me leí “El jefe Seattle” y me gustó mucho [it’s something we’re not normally taught and it could be interesting. I read “Chief Seattle Speech” in 5th or 6th grade and I liked it very much’]

‘because it teaches a lot of knowledge and values that it would be interesting to introduce to students in Spain’

‘it contributes to a lot of knowledge to children, specially culturally, and children’s literature books are a very fun one [sic] to learn’

‘I consider it essential to learn about different cultures and to know the literature and art of lesser known groups’

The question ‘Would you use these materials in a primary class for real?’ (Figure 4) also had an increase of ‘Yes.’ Nevertheless, despite the positive trend the results show, from a critical literacy point of view, the following question ‘Do you think you have stereotypes about Native Americans?’ (Figure 5) reflects a confidence in recognizing one’s own bias that may be misguided. Indeed, while the projects created show an overall remarkable respect for Native American culture, as well as understanding and empathy in the treatment of the stories, some of the activities created for the project reflect certain clichés such as the conception of a final event in which children ‘dress up as Indians’, or the lack of tribal context of the authors or the groups they deal with. And it is vital to bear in mind one of the main tools to dismantle prejudices is precisely the recognition of tribal specificity by bringing the cultural context of the authors’ Indigenous group into the classroom (White-Kaulaity, 2006, p. 9), as the simplification of indigenous cultural identities is at the basis of the construction of stereotypes.

Figure 4. Willingness to use children’s Native American literature in class

Figure 5. Perception of self-bias

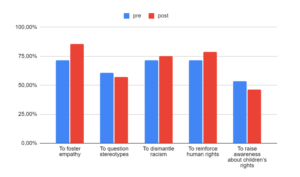

As a matter of fact, in Figure 6 (‘What may be some of the benefits of using Native American literature in primary school?) we can observe a slight decrease in the item ‘to question stereotypes’, which might reflect a lack of awareness about the importance of the detection of stereotyping. As stated before, the projects contain instances in which we cannot oversee the failure to deconstruct preconceptions. Such is the case of the project on For a Girl Becoming, where a number of student teachers state:

Women continue in this process to achieve equality in a society where there are still some signs of imbalance of power between men and women. Regarding Indigenous women, there is still much more to do. They do immense activities without receiving any payment or encouragement and despite their enormous workload. Likewise, they are not valued by their husbands or relatives. Some women think this is normal, others are told by their husbands and mothers-in-law that it is ‘their obligation and duty as a woman’.

The source students retrieved this information from is unknown, and that may be precisely the problem – insufficient research – but it sounds like a Eurocentric generalization, interpreting that any culture, apart from Euro-American, is ignorant of human rights. However, the same student teachers used For a Girl Becoming as a mentor text in their paper to encourage pupils to tell their own birth stories, not forging stories ‘about’ Native Americans, but to tell their own stories, using their perspectives from inside their communities and families.

Another group, working with Keepers of the Animals, designed activities around the circle dance, but whereas in their book Caduto and Bruchac (1991/1997) suggest this activity as a performance ‘to honor and to give praise to the animals for the many gifts we perceive from them’ (p. 46), the activity proposed by the group is not well defined and only scratches the surface. The final project is tribally specific, though, and gives creation stories the dimension of cultural history, dismantling the fallacy of labelling western creation accounts as Bible stories, whereas Indigenous creation stories are labelled as folklore, or treating a group of creation stories as fiction while the other is accepted as truth. As Reese points out, ‘critical Indigenous literacy forefronts the historically marginalized treatment of Native stories … Our creation stories are as sacred to us as Genesis is to Christians: we do not view them as folktales’ (2018, p. 390).

As we can see, the pre-service teachers in this study demonstrated a capacity to disarm their own stereotypes, despite failing to recognize them in other cases. That is why assessment is vital. Remedial critical assessment would have been pertinent in this experience, however the course schedule did not allow it.

Figure 6. Objectives of the use of children’s Native American literature

Finally, the last question of the post-questionnaire exceeded expectations, since when asked if they would like to continue learning about Native American literature, 75% answered yes, compared to 25% no, which indicates that the project has been successful in activating curiosity. The open-ended answers to the penultimate question are also worth mentioning: ‘What have you learnt about Native American literature?’

‘que es muy necesario que le lean estos libros enclase ya que puede ayudar mucho a los niños a empatizar con los niños nativos y para ver cómo viven’ [it is necessary for children to read these books in class, so they can help them empathize with Native children and see how they live]

‘I have learned things that I did not know and I have found them very interesting’

‘Bailes típicos y canciones por ejemplo’ [typical dances and songs, for example]

‘I have learned about what their culture is like and how it is different from our own in some aspects’

‘It is interesting’

‘Their culture, custom, resources, clothes, language …’

‘He aprendido que la literatura Nativa Americana va más allá de una historia, y habla de una cultura’ [I have learned that Native American literature is more than a story, it talks about culture]

‘very important values such as empathy or kindness and companionship’

‘I have learned many new concepts’

‘I have learned many things, especially many cultures that enriches people a lot’

‘I have learned about Native American traditions, their way of life, and the values they hold’

As student teachers’ short answers testify, the study served to introduce Native American children’s literature as a possibility in Spanish English language classes, providing pre-service teachers with a glimpse into challenging literature, with themes that are ‘unfamiliar to the reader’ (Ommundsen et al., 2022, p. 8). In the same way, the selection of the books used in this experience not only posed a challenge to the readers unfamiliar with Native American children’s literature but also encouraged students that were already committed to intercultural practices.

Discussion and Conclusion

Bearing in mind the objectives of critical literacy, intercultural citizenship, perspective challenge, compelling literature, and feasibility, we can conclude that this educational experience has fulfilled its purposes. This is based on the results of the questionnaires, but also on the evaluation of the projects presented by the groups, in which the students have demonstrated the use of the tools acquired and the application of new knowledge.

Despite the lack of recognition of self-bias, in some cases, and the reproduction of certain stereotypes, and taking into account that even in the US university context, student teachers suffer from a notable lack of knowledge regarding tribal diversity, cosmogony and myths in Native literature (Zitzer-Comfort, 2008, p. 160), we can affirm that the participants in this study have not only learned from other literatures, but have also learned about Indigenous pedagogies to some extent, or at least to acknowledge their existence. Both the final papers and the responses to the questionnaires reflected an empathy and fascination that exceeded the expectation of this study. The participants brought their own experience to the project, they did research, read articles and information in English and developed strategies to create innovative projects. Nevertheless, although there is so much to be done, the most moving aspect of this study has been the expectation it has generated in the pre-service teachers involved in the project, as critical thinking is a lifelong learning that can only be sustained by curiosity.

In fact, I cannot help but wonder what students might have thought when the Residential School graves in Canada made international headlines in June 2021, having investigated this topic through the picturebooks Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi’s Canoe. It would also be interesting to have seen their reaction when in September, some Spanish right-wing politicians released statements such as ‘España llevó la civilización a América a través de la evangelización’ [Spain brought civilization to America through evangelization] or ‘El indigenismo es el nuevo comunismo’ [Indigenism is the new communism].[ii] I like to think the students might have activated their critical literacy learning to deconstruct those intellectual naiveties. In this profession we do not exactly know how and when the crops are going to germinate, but we do get to plant the seeds.

Bibliography

Caduto, Michael, J. & Bruchac, Joseph. (1988). Keepers of the Earth. Fulcrum Publishing.

Caduto, Michael J. & Bruchac, Joseph. (1997). Keepers of the Animals. Fulcrum Publishing.

(Original work published 1991)

Caduto, Michael J. & Bruchac, Joseph. (1994). Keepers of the Night. Fulcrum Publishing.

Caduto, Michael J. & Bruchac, Joseph. (1994). Keepers of Life. Fulcrum Publishing.

Campbell, Nicola I., illus. Kim LaFave. (2005). Shi-shi-etko. Groundwood Books.

Campbell, Nicola I., illus. Kim LaFave. (2007). Shin-chi’s Canoe. Groundwood Books.

Child, Brenda J., illus. Jonathan Thunder, trans. Gordon Jourdain. (2018). Bowwow Powwow.

Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Harjo, Joy, illus. Mercedes McDonald. (2009). For a Girl Becoming. The University of Arizona Press.

Ortiz, Simon, illus. Sharol Graves, S. (2017). And the People Shall Continue. Lee and Low Children’s Book Press. (Original work published 1977)

Tapahonso, Luci, illus. Eleanor Schick. (1995). Navajo ABC: A Diné Alphabet Book. Simon & Schuster.

Tapahonso, Luci. (1997). Blue Horses Rush In. The University of Arizona Press.

Tapahonso, Luci, illus. Anthony Chee Emerson. (1999). Songs of Shiprock Fair. Kiva Publishing.

References

Allen, P. G. (1983). Studies in American Indian literature: Critical essays and course designs. The Modern Language Association of America.

Bland, J. (2013). Children’s literature and learner empowerment. Bloomsbury.

Bland, J. (2018). Introduction: The challenge of literature. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8–18 year olds (pp. 1–22). Bloomsbury Academic.

Cook-Lyn, E. (1996). Why I can’t read Wallace Stegner and other essays. University of Wisconsin Press.

Council of the European Union (2018). Council Recommendations of 22 May 2018 on key competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.C_.2018.189.01.0001.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AC%3A2018%3A189%3AFULL

Deloria, V., Jr. (1994). God is red. Fulcrum Publishing. (Original work published 1972)

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogía del oprimido. Siglo XXI Editores. (Original work published 1970)

Hall, G. (2015). Recent developments in uses of literature in language teaching. In M. Teranishi, M., Y. Saito & K. Wales (Eds.), Literature and language learning in the EFL classroom. (pp. 13-25). Palgrave Macmillan.

Janks, H. (2013). Critical literacy in teaching and research. Education Inquiry, 4(2), 225-242. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i2.22071

Krashen, S. (2009). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press. (Original work published 1982) http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_practice.pdf

Krashen, S. & Bland, J. (2014). Compelling comprehensible input, academic language and school libraries. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2(2), 1-12.

Leitich Smith, C. (2019, January 4). Illustrator interview: Jonathan Thunder on Bowwow

Powwow. Cynsations: Celebrating Children’s & Young Adult Literature. https://cynthialeitichsmith.com/2018/05/illustrator-interview-jonathan-thunder/

Miralles-Alberola, D. (2021a). Native American children’s literature in the English language education classroom. In A. M. Brígido-Corachán (Ed.), Indigenizing the classroom: Engaging Native American/First Nations literature and culture in non-Native settings (pp. 127-145). Publicacions de la Universitat de València.

Miralles-Alberola, D. (2021b). Aprendizaje intercultural, lectura fascinante y alfabetización

crítica a través de la literatura infantil nativo-americana en inglés para primaria. In África Martos Martínez, Ana Belén Barragán Martín, María del Mar Molero Jurado, María del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes, María del Mar Simón Márquez & José Jesús Gázquez (Eds.), Innovación Docente e Investigación En Educación y Ciencias Sociales: Nuevos Enfoques En La Metodología Docente (pp. 387-398). Dykinson, S.L. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2gz3swq.34

Ommundsen, Å. M., Haaland, G. & Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2022). Exploring challenging books in education: International perspectives on language and literature learning. Routledge.

Owens, L. (2001). Mixed blood messages: Literature, film, family, place. University of Oklahoma Press. (Original work published 1998)

Rainwater, C. (1999). Dreams of fiery stars: The transformations of Native American fiction. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Reese, D. (2013). Critical indigenous literacies. In J. Larson & J. Marsh (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of early childhood literacy. (pp. 251-263). SAGE.

Reese, D. (2018). Critical Indigenous literacies: Selecting and using children’s books about Indigenous peoples. Language Arts, 95(6), 389-393

Roche, J. (1999). Asa/Forrest Carter and regional/political identity. In P. D. Dillard & R. L. Hall (Eds.), The southern albatross: Race and ethnicity in the American south (pp. 235-274). Mercer University Press.

Slapin, B., Seale, D. & Gonzales, R. (2000). How to tell the difference: A guide to evaluating children’s books for anti-Indian bias. Oyate.

Weaver, J. (1998). That the people might live: Native American literatures and Native American community. Oxford University Press.

White-Kaulaity, M. (2006). The voices of power and the power of voice: Teaching with Native American literature. The ALAN Review 34(1), 8-16.

Zitzer-Comfort, C. (2008). Teaching Native American literature: Inviting students to see the world through Indigenous lenses. Pedagogy, 8(1), 160-170. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-2007-031

[i] In Latin America, Indigenism was a cultural and literary movement that developed during the 19th and 20th centuries and focuses on the problems of Indigenous populations, but with a messianic white saviour perspective, since it is a characteristic that the authors were creole middle and upper classes. Nevertheless, it was a necessary movement in its context that produced intellectuals and writers such as Miguel Angel Asturias, Clorinda Matto de Turner, José Carlos Mariátegui, Rosario Castellanos or Manuel González Prada. About the Spanish right-wing politicians’ statements, some can be found in the following links https://elpais.com/espana/2021-09-29/los-desatinos-de-ayuso-sobre-el-indigenismo-y-el-legado-de-espana-en-america.html; https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x84k3cf.

[ii] The results of this small research were published in the volume Innovación docente e investigación en Educación y Ciencias Sociales: nuevos enfoques en la metodología docente, published in Spanish in December 2021. However, the current paper tries to go deeper into some aspects of the process that were left aside, including a focus on the adequation to the Spanish educational system, the selection criteria for the materials, aspects of Native views, the students’ experience with Native American children’s literature, and on presenting a detailed description of the project in order to provide suggestions and ideas for other teachers.