Contents

| Editorial: Stereotyping versus Diversity Competence – Janice Bland | ii |

| Book Reviews – Sandie Mourão Jane Spiro |

1 6 |

| Legally Scripted Fictions: Fathers and Fatherhood in English Language Picturebooks with Children from Refugee Backgrounds – Ekaterina Strekalova-Hughes, Nora Peterman and Kylee Lewman | 10 |

| Opening a Dialogic Space: Intercultural Learning through Picturebooks – Sissil Lea Heggernes | 37 |

| Social Model Thinking about Disability through Picturebooks – Gail Ellis | 61 |

|

Teaching English to Young Learners: More Teacher Education and More Children’s Literature! – Janice Bland |

79 |

|

Recommended Reads – Luciana Fernández, Laura McWilliams, Helen Chapman, Sarah Howell |

104 |

[End of Page i]

Editorial: Stereotyping versus Diversity Competence

Janice Bland

Welcome to the November 2019 issue of Children’s Literature in English Language Education! In one way or other, all the articles in this issue try to confront stereotyping. Currently we are seeing all too clearly the destructive consequences that can follow prejudice and intolerance. Intercultural learning is central to English language learning – the idea that the ability to change perspective is key when using a lingua franca, broadening opportunities to interact sensitively with people from other cultures. However, intercultural competence demands in addition acquiring fresh and thoughtful perspectives on one’s own cultural identities. Our multiple sociocultural identities include not only national and ethnic backgrounds, but also smaller social groups, such as family and school cultures. As Dervin (2017, p. 245) argues, it is ‘increasingly important to intersect culture and other identity markers (gender, social class, language, etc.)’. Selby and Pike (2000, pp. 142-143) discuss the inner dimension of global education as ‘a voyage along two complementary learning pathways. While the journey outwards leads learners to discover and understand the world in which they live, the journey inwards heightens their understanding of themselves and of their potential’. Both understanding and criticality belong to intercultural learning, and must be highlighted in order to achieve critical thinking and overcome, to some extent, stereotyping of different cultural groups.

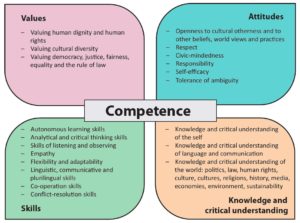

The tendency of any group to maintain unreflecting conformity of perspectives leads to what is known as ‘groupthink’, and the submerging of individual creativity and autonomy as well as critical evaluation of other points of view. Groupthink creates one-dimensionality and in-group bias, and leads to the exclusion of others who feel they do not belong. In order to overcome stereotyping and essentializing, critical understanding must be seen as an aspect of both intercultural competence and diversity competence. A competence model in the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (see Figure 1) stipulates twenty competences ‘that need to be acquired by learners if they are to become effective engaged citizens and live peacefully together with others as equals in culturally diverse democratic [end of page ii] societies’ (Council of Europe, 2018, p. 65). The focus is on valuing diversity, tolerance of ambiguity, practising empathy and critical understanding – in a nutshell diversity competence:

Figure 1: Extracted from Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (2018, p. 38) (https://www.coe.int/en/web/education/competences-for-democratic-culture)

Is the diversity we experience amongst the children and teenagers in our classrooms mirrored in our classroom materials? A difficulty that haunts ELT is that course books often try to teach about different national cultures. Yet the shapeshifting nature of cultural groups means that culture cannot be taught without resorting to stereotypes, with the insinuation that certain colourful or salient characteristics (likely to be seen as backward) belong to all members of the group. Trying to teach about different cultures can easily lead to cultural essentialism, the [end of page iii] suggestion that the essence of a cultural group is common to all members of that group at all times, thus reinforcing stereotypes rather than challenging long-established but unexamined beliefs. Articles in this issue (as in previous issues of Children’s Literature in English Language Education) reflect dynamic and open interpretations of culture: ‘There is a wide span between static and essentialist interpretations of culture on the one hand and dynamic and open interpretations on the other’ (Lenz & Nustad, 2019, p. 12).

All teaching resources must be subjected to critical evaluation by teachers, together with their students, in order to develop students’ ability to question what appears to be normal just because it is familiar, and making, as Kramsch puts it, ‘one’s own ways of thinking, speaking and behaving seem as natural as breathing, and the ways of others seem “unnatural” ’ (1996, p. 2). A study conducted by Brown and Habegger-Conti on the images of indigenous peoples in Norwegian ELT course books, found the accumulated effect of the photos was to ‘create “us” / “them” dichotomies between “whites” who are shown as active, complex and technologically advanced, and indigenous peoples who appear passive, primitive and simple’ (2017, p. 26). As the researchers show, it is just as important to learn to read visual representations critically as text representations, brought into the open in the classroom and discussed so that they are less stealthily manipulative. English learners are all too often ‘positioned to view indigenous people as belonging in the past’ (2017, p. 28).

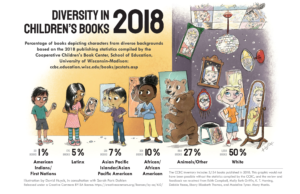

There is no suggestion that children’s literature, in contrast to course books, is always free from stereotyping, as the first article in this issue on the portrayal of fathers in picturebooks with children from refugee backgrounds indicates. Children’s literature is now widely critically scrutinized and analysed for hidden, often unintentional, ideological stances in text and images. There is indeed much still to be done, so that children can both see themselves mirrored in their stories, and mirrored in a way that allows them to recognize the reflection as valuing their cultural identity. For example, Figure 2 is an infographic that shows to what extent particular populations are depicted, and how well they are reflected, in over 3000 children’s books that appeared with US publishers in 2018: [end of page iv]

Figure 2: Diversity depicted in children’s books from US publishers (Huyck & Dahlen, 2019)

The first paper in this issue, ‘Legally Scripted Fictions: Fathers and Fatherhood in English Language Picturebooks with Children from Refugee Backgrounds’ (Strekalova-Hughes, Peterman & Lewman) examines representations of fathers and fatherhood in 43 picturebooks featuring children from refugee backgrounds. Ideology is seldom far from such representations, in that fathers are frequently entirely absent, or represented one-dimensionally as tied to their legal refugee status, at the expense, as the authors conclude, ‘of multifaceted cultural and interpersonal aspects of fatherhood’ (p. 10).

Heggernes’ paper follows, ‘Opening a Dialogic Space: Intercultural Learning through Picturebooks’, and explores classroom exchanges around Peter Sís’ graphic memoir, The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain. Based on the theoretical perspective that all interpersonal communication can potentially become intercultural communication, Heggernes shows in her [end of page v] research how a participative ethos will foster students’ intercultural learning in ELT, supporting their exploring and evaluating of visual text, and encouraging changing perspective.

Ellis’s paper, ‘Social Model Thinking about Disability through Picturebooks’ considers the lack of representation of children with disabilities in picturebooks. The article outlines ways of promoting an inclusive culture in the primary ELT classroom with picturebooks, showing respect and equal commitment to all learners. Ellis examines the social model of disability, which advocates a positive approach to disability, and ‘shows how individuals are disabled by barriers erected in society, not by their impairment or difference, and focuses on the changes required in society in order to adapt to the needs of persons with disabilities’ (p. 62).

Bland, in her paper ‘Teaching English to Young Learners: More Teacher Education and More Children’s Literature!’, reports on the worldwide stereotype that both phenomena – teaching English to young learners and children’s literary texts – are simple matters. Bland highlights the importance of high-quality input for young language learners, and attempts to outline the combined effect of this double stereotype on primary-school teachers, teacher education and teacher development, and thus, finally, on society and the children themselves.

This issue also features two book reviews: Spiro discusses Arting and Writing to Transform Education: An Integrated Approach for Culturally and Ecologically Responsive Pedagogy and Mourão examines The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks. Both books are found to be inspiring in very different ways. The issue ends with a tribute to Judith Kerr, who died this year. She is an author who certainly inspired me, with her picturebooks but above all with her account of her experiences as a child refugee, the nightmare clearly there in the distance but from a child’s perspective with more humour than doom, When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit.

Many thanks to all who have contributed to this issue.

Happy reading,

Janice Bland [end of page vi]

References

Brown, C. W. & Habegger-Conti, J. (2017). Visual representations of indigenous cultures in Norwegian EFL textbooks. Nordic Journal of Modern Language Methodology, 5(1), 16-34.

Council of Europe (2018). Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture. Volume 1. Context, Concepts and Model. Retrieved 26 November, 2019 from https://rm.coe.int/prems-008318-gbr-2508-reference-framework-of-competences-vol-1-8573-co/16807bc66c

Dervin, F. (2017). Human Rights education and intercultural education. In J. Zajda & S. Ozdowski (Eds), Globalisation, Human Rights Education and Reforms Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 239-249.

Huyck, D. & Dahlen, S. P. (2019 June 19). Diversity in Children’s Books 2018. sarahpark.com blog. Created in consultation with Edith Campbell, Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp. Retrieved 26 November, 2019 from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/.

Kramsch, C. (1996). The cultural component of language teaching. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 1(2), 1-13. Retrieved 26 November, 2019 from https://tujournals.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/index.php/zif/article/view/741/718

Lenz, C. & Nustad, P. (2019). Dembra – Theoretical and Scientific Framework. Retrieved 26 November, 2019 from https://dembra.no/en/om-dembra/

Selby, D. & Pike, G. (2000). Civil global education: Relevant learning for the twenty-first century. Convergence: An International Journal of Adult Education, 33(1-2), 138-149. [end of page vii]