| The Page IS The Stage: From Picturebooks to Drama with Young Learners

Carol Serrurier-Zucker and Euriell Gobbé-Mévellec |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This paper shows the close link between picturebooks and theatre, and how the books can be dramatized with young learners. In this process the children can creatively draw on and manipulate the language they are acquiring while becoming increasingly autonomous in their learning. The task-based approach promoted by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), which has shown its worth for the acquisition of communicative competences in language classes at secondary level and above, is not always easily applicable in primary classes. The young learners’ often limited linguistic abilities make project work and meta-language discussion difficult in the foreign language. Teaching foreign languages through drama can provide an interesting solution.

The creativity, whole-body experience and social interactivity involved in drama teaching produce high levels of motivation and an ideal method for language practice and acquisition. Storytelling is widely accepted as a valuable vector in the foreign language classroom, and allowing the young learners to become dynamically involved in the process takes it one step further. In this article we first demonstrate the inherently theatrical nature of picturebooks. The paper then reports on a project researching the use of drama in language teaching with young learners. The project commenced with drama activities inspired by two selected picturebooks, which led on to the presentation of powerful dramatic scenarios intimately relating to the children’s lives.

Keywords: picturebook, drama, primary-school languages, foreign language learning, task-based project [End of Page 13]

Carol Serrurier-Zucker was born in South Africa. She has a PhD in South African literature and has been an English Lecturer and Teacher Trainer at the ESPE Académie de Toulouse, Université de Toulouse II, since 2002. She is a member of OCTOGONE-Lordat laboratory, researching foreign language teaching at primary level.

Euriell Gobbé-Mévellec is a Spanish Lecturer and Teacher Trainer at the ESPE Académie de Toulouse, Université de Toulouse II. She has a PhD in Spanish children’s literature. She is a member of LLA-CREATIS laboratory and coordinates youth activities for the theatre group Les Anachroniques.

Introduction

The children’s picturebook today is one of the most perfected forms within children’s literature, both aesthetically and as a reading medium. The collaboration between authors, artists, illustrators, graphic designers and publishers has created a fertile field of experimentation and innovation with a continual renewal of forms of reading and communication (Van der Linden, 2005). And it is often through seeking its inspiration in theatrical techniques that the picturebook finds new ways of interacting with its readers.

Picturebooks strive to bring language alive and move the reader, so we found it pertinent to experiment with this medium to bring the discovery of a foreign language in primary school alive and move young learners through dramatic creation. We postulated that the communicative wealth of the picturebook would represent a solid, productive basis from which to imagine drama activities aimed at initiating children into a foreign language. This article aims to explain the theoretical and practical steps of a project, still in progress, which if it proves its value, hopes to help give drama a greater place in the methodology of primary school foreign language teaching in France.

Foreign Language Teaching through Drama at Primary School

Foreign (and regional) languages have been part of primary-school curricula since 2002 in France, taught in the last four years of primary school with an initiation taking place in the first year. Fifty-four hours of language are taught per year or one and a half hours per [End of Page 14] week. The level A1 of the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001) is the objective to be reached by the end of primary school.

Progressively over the last decade, primary school teachers in France have taken on the additional task of foreign language teaching, with pitifully few hours devoted to language training (in both initial and in-service teacher training) each year. Last year almost 97 per cent of primary language teaching in the Académie of Toulouse, the region comprising eight geographical départements in which the authors work, was done by the class teachers themselves. The primary language curriculum1 mentions a choice of eight languages (English, Spanish, German, Italian, Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese and Russian), although the reality of what schools can offer, in conjunction with demand, centres mainly on English with a moderate interest in Spanish in this southwestern Académie, as shown in Table 1.

| Language | Proportion choosing this language in Toulouse Académie |

| English | 89,77% |

| Spanish | 9,19% |

| German | 0,91% |

| Portuguese | 0,10% |

| Italian | 0,02% |

Table 1. Figures for foreign languages taught in 2012-13 in the Toulouse Académie.

The teachers do a commendable job, given that most of them are not language specialists; nevertheless some admit to finding the task difficult and we are convinced that the integration of drama in language classes could offer some solutions. Drama does not figure in teaching curricula in France, so it is up to individual teachers to take the initiative and demonstrate the benefits it can offer.

What is interesting in drama is the process of activating a story, which activates the young learners themselves as they engage physically and emotionally with imaginary situations while communicating in a foreign language. The number of hours of language teaching in the French primary-school curriculum is insufficient to provide the linguistic [End of page 16] immersion necessary for the acquisition of a second language, but drama is a concentrated learning experience which allows for the optimisation of the limited time available.

Drama is a multi-sensorial approach to language learning, which brings the lessons to life. It implies an ‘enactment’ of language, whereby the body and not just the mind is part of the learning process (Schmidt, 2006, p. 101). The repetition inherent in and necessary to memorisation can become tiresome, whereas the objective at the end of drama work – acting – transforms repetition into the challenge of rehearsing and improving one’s performance. Linguistically, one can observe a tendency in France to teach lists of vocabulary accompanied by a specific structure that the young learners are incapable of reusing in a creative, autonomous manner (Audin, 2003, p. 13). Dramatizing a story is a complex project, in the task-based approach, which generates the need for real communication; it is an experience of linguistic immersion where one uses language in context and authentically.

The association of drama and children’s imaginary games is similar to the process of learning a foreign language in a country where the language is not spoken. To translate and paraphrase Prisca Schmidt, drama provides the appropriate framework to justify the ‘as if’ we were elsewhere, in another country where they speak a different language… it provides the pedagogical answer to the paradox of teaching a foreign language in the non-natural, closed environment of a classroom… which can become an asset if one establishes a kind of playful complicity with the pupils around playing/acting (Schmidt, 2010, p. 33).

The Use of Picturebooks

Our method uses the picturebook as a starting point for drama. Picturebooks are defined by the strong presence of the images accompanying the text, pictures which do not merely illustrate or embellish the story, but are an integral part of the narrative (Van der Linden, 2006). The global organisation of the picturebook is visual with the text being one of the components of the multimodal system.

The pictures are at once attractive, appealing to the imagination and calling for identification and empathy from the reader while providing a bridge across the text to comprehension for a pupil with limited linguistic skills. This double mode of communication – iconic (pictorial) and textual – optimizes the transmission of the [End of Page 16] message. In our current visual age, children are more and more exposed to images. It is important, as Ellis & Brewster (2002, p. 8) and Mourão (2013) put it, to help them develop their ‘visual literacy’.

We thought it interesting, therefore, to transpose the situation of children not yet able to read, to that of children in the learning phase of a foreign language, finding themselves faced with a language they do not yet master, but capable of finding clues for comprehension in the pictures. Other advantages of picturebooks explain why their use is sought after in the language classroom: the relative simplicity of the text and its brevity – often based on repetitive structures – facilitating not only understanding but memorisation. The narrative frame often allows for the construction of a coherent progression where learning is not justified by linguistic objectives alone. It also enables the articulation of a series of activities, maintaining a narrative link between them: songs, rhymes, dances, manual activities, games, and so forth. The picturebook works as an interactive support, which permits the channelling of the young learners’ physical energy and its transformation into intellectual energy (Perrot, 1999, p. 117).

As for the images, they open up avenues for the imagination to give shape to, voice and act out the story; they constitute a factor of motivation and allow for immediate reading where language might be an obstacle; their attractive colours and forms appeal to children’s emotions, contributing to the strong affective charge conveyed by picturebooks. These books are a familiar presence to many young learners, having been part of their lives from early childhood, associated with moments of pleasure. They mostly evoke themes and characters that are directly related to the young learners’ lives and preoccupations. This reassuring function can work to counterbalance any uncertainties and worries associated with learning a foreign language. Finally, and this is what interests us most, there is a certain theatrical content in the picturebook which invites its dramatization.

Manifestations of Theatricality in Picturebooks

The theatre is very often present in picturebooks, far more often than one may think. It may appear explicitly with the book functioning like a little theatre which one opens up – or implicitly, without losing its theatricality for all that. We can define three main categories of theatricality in the picturebook, each compatible and (as shown below) often [End of Page 17] ´interacting with the others. Using the triadic typology of the sign as defined by Charles Peirce (1998, p. 289-300), index, icon and symbol, we can describe the presence of the theatre in picturebooks in the following way:

1. The theatre can first be present in the picturebook as a theme or motive. The book can show a theatre or a play. The theatrical sign works as an icon in a relationship of similitude with its referent. Numerous books act as theatres, like the pop-up version of a well-known classic: Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler’s The Gruffalo Pop-Up Theatre Book (2008), which allows the young readers to create their own theatres and versions of the story.

2. The theatre can also be present through the borrowing of certain techniques: puppets, shadow theatre, the commedia dell’arte, the theatre of objects or of images often finding their way into the pages of picturebooks. We see here an indexical relationship to the theatre, where a part of it is appropriated into use in the story.

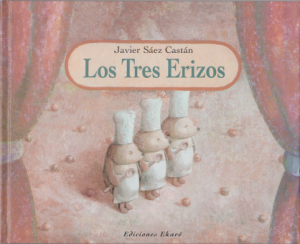

Figure 1. Front and back covers of Los Tres Erizos by Javier Sáez Castán

The book Los Tres Erizos (Javier Sáez Castán, 2003) shows red stage curtains on its front cover, and on the back cover, the three eponymous characters are raising their chef’s hats and taking a bow like actors at the end of their performance (see Figure 1). The subtitle of the book indicates that the narrative takes the form of a ‘mime show in two acts’ [End of Page 18] (‘pantomima en dos actos’). These theatrical indices convey a glossy tint to the narration, which evolves in tableaux, with the text added in caption form or inside speech bubbles.

3. Third, the theatre can function symbolically in the picturebook, echoing certain of the aspects or concerns of childhood. Make believe and role-playing are often used by characters in their attempts to understand and come to terms with the sometimes thorny task of growing up and forging an identity. This symbolic function also reflects the literary process of interacting with a character. The characters and the roles they might adopt in the story constitute questioning spaces – and the picturebook becomes an imaginary stage, which can represent a cathartic value for the young reader as well as for the protagonist, a safe space in which they can experiment by playing.

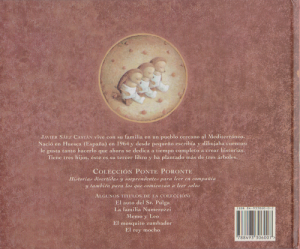

Let us mention a few other examples, which may fit into this framework of the theatrical sign. Amandina (Sergio Ruzzier, 2008) tells the story of a little dog with many talents for the stage, but who is terribly shy (see Figure 2). She decides to face her fear by renting a theatre to put on a show. Here, the theatrical process, which includes organising the hall and creating the costumes and scenery, is omnipresent and all three types of sign can be found. The theatre is present as a physical space – an icon; it is present in the indices of acting, song, dance, magic, etc. performed by Amandina, and symbolically through her inner journey through fear and rejection towards self-confidence and achievement.

Figure 2. Front cover of Amadina by Sergio Ruzzier

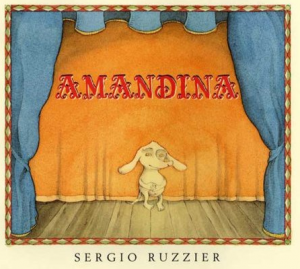

In Izzy and Skunk (Marie-Louise Fitzpatrick, 2000), the theatre is present in the indexical presence of the puppet, Skunk, the beloved toy of Izzy, a little girl who has many fears (see Figure 3). The puppet is also imbued with an obvious symbolic value. Its [End of Page 19] presence gives Izzy the courage needed to face and overcome her fears. When Skunk is stolen by a cat, Izzy surpasses herself in efforts and courage to find him (in the branches of a tree, which she climbs in order to rescue him) and henceforth interiorizes the courage that she had previously projected onto Skunk.

Figure 3. Front cover of Izzy and Skunk by Marie-Louise Fitzpatrick

Big Bad Bun (Jeanne Willis and Tony Ross, 2009) illustrates the relationship of character to actor through the epistolary narrative of a young rabbit called Fluff, a story based on pretence. Fluff explains to his parents in a note that he has left home to join a gang. The symbols of the transformation of fluffy bunny into bad rabbit are his leather jacket, his pierced ear and a tail dyed green and blue (see Figure 4). Each illustration shows the fake gangster’s bold misbehaviour. In reality, he is hiding at his grandmother’s house because he has obtained a bad school report and is afraid of being scolded by his parents. The role he adopts, imagining himself big and strong, and capable of transgressing rules, allows him to discharge his fear of parental wrath.

Figure 4. Front cover of Big Bad Bun, by Jeanne Willis and Tony Ross [End of Page 20]

The moral addressed to the reader on the last page is: ‘you can’t always believe everything you read’. The deception is total and the reader does not discover it until the end, unlike in Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak, 1963) where Max’s identity as a little boy is never in doubt, since his face shows through his wolf costume.

Orality and Picturebooks

The dramatic nature of the picturebook comes from the relationship between the images and the oral nature of the narrative. According to Isabelle Nières (1991), this orality can be seen as a modern-day version of the traditional fairy or folk-tale oral storytelling, where dramatic delivery of the story is required. The onomatopoeia, repetitions, rhythms and sonorities, the tight construction of the double-page spreads, all structure and organize the reading and subsequent dramatic adaptation.

Another element is the spectacularization of the text: the size, shape, colour and density of the font used and its distribution on the page all lend intensity and emotion to the speech (Van der Linden, 2005). For example, in Noko and the Night Monster (Fiona Moodie, 2002), the Night Monster which terrifies Takadu is never shown in image, but is immediately recognized in the bold shadowy capital letters that are used to spell out its name, just as the trembling letters used for ‘shiver’ and ‘shake’ show Takadu’s fear, and the tailing off of the word ‘asleep’ indicate that the timorous animal has finally dropped off, so we need to lower our voice to a whisper. In this way, the text supplies clues as to the intonation and emotion to communicate when reading or dramatizing the story.

In the widest possible sense of theatricality, one can say that the drama is conveyed by the visual aspect of the picturebook, which acts in a similar way to the stage directions in a play (Bernanoce, 2007). To take one example, the frequent explosion of the textual block in picturebooks and its displacement into the zone of the image plays the same role as the stage direction which indicates who is speaking. The dialogue is ‘geographically’ associated with the image of the character uttering it, in a convention close to that of speech bubbles in comics and graphic novels. In the Meg series by Helen Nicoll and Jan Pienkowski, one sees a frequent co-existence of different iconotextual systems, conveying the source of the speaker and complementing the action. In Meg’s Eggs, for example, [End of Page 21] speech bubbles are used for the onomatopoeia and the text is scattered over the page, positioned near its speaker or reinforcing the action.

In conclusion, it is not the degree of visibility of the theatre that proves the pertinence and importance of the link between it and the picturebook, but the role it plays in renewing the systems of representation, bringing the narrative to life and rendering it more interactive. Sometimes the theatre becomes a metaphor of childhood. All these arguments make the combined use of picturebook and drama appropriate for use in a language class.

From Theatricality to the Dramatization of a Picturebook

In order to test our theory that the incorporation of drama into the language classroom in primary school would motivate the class and have a positive consequence on the oral communicative performance, we developed a project in collaboration with two primary school teachers2 in Toulouse who teach English and Spanish respectively to their classes. The Spanish teacher used the same picturebooks as the English teacher, in translation. Altogether 39 young learners in the last two years of primary school (10–12 year-olds) tested the units we had created. The teachers kept reflective diaries about the classes and their thoughts and observations of the experience and at the end of the units, the pupils answered a questionnaire.

We developed two units of six lessons each dramatizing a picturebook. The first was: A Bit Lost (Haughton, 2010). The book has a repetitive structure, which lends itself particularly well to this kind of theatrical application. A baby owl falls from its nest and then looks for its mother, meeting up with a squirrel, a bear, a rabbit and a frog. The second, Crafty Chameleon (Mwenye Hadithi, illustrated by Adrienne Kennaway, 1987) is a South African picturebook with three main characters: a chameleon, a leopard, a crocodile, and as many minor characters as one needs in order to include everyone: other animals, birds and ants. It tells the story of a little Chameleon (see Figure 5) who eventually triumphs over a big Leopard and scary Crocodile, who have been bullying him and his animal friends, proving that brains are better than brawn. [End of Page 22]

Figure 5. Front cover of Crafty Chameleon.

The steps involved in dramatizing the story

- Determine how to tell the story. For Crafty Chameleon, the whole story was told at the beginning of the first class, whereas for A Bit Lost, a progressive approach was chosen to stimulate the imagination and allow the young learners to guess what would happen next. We supplied a scripted version of each text to the teachers but, obviously, more advanced groups, or those experienced in drama, could create their own dialogue.

- Determine the linguistic objectives (lexical, structural, phonological…). Consulting with the book and the teachers, we determined what language would be necessary, what was already acquired and what would be taught during the unit. We chose the vocal activities like tongue twisters, rhymes and songs, to be used during the lessons and, in Crafty Chameleon, during the staging.

- Determine the characterisation. The young learners needed to learn their names, find an attitude, a walk, a facial expression for each character using various drama techniques like mime, pair work and improvisation of the different interactions [End of Page 23]between the characters. As the lessons progressed, they found voices and styles of expression based on the animals’ sounds.

- Work on the emotions using drama techniques. The emotions were worked on through mime, frozen images, improvised interactions, first collectively, then individually in the roles of the different characters. For Crafty Chameleon, we used a spacial activity for the four main emotions of the story – feeling angry, frightened, tired and happy – each represented in a room in a fictional ‘house of emotions’. The young learners moved through the house reciting a rhyme, a transformation of ‘Five Little Monkeys’ into ‘Five Little Leopards’, adopting the movement, expression and voice of the emotion and character being mimed.

- Rehearse the actions of the story. The verbs were learnt through movement and games, associating language and action. Appropriate warm-up activities were used to start each lesson to prepare the young learners for the physicality of drama as well as to forge the climate of confidence and cooperation essential to the risk taking involved in acting. Each session started with the pupils in a circle taking deep breaths and relaxing their bodies. Activities like throwing imaginary balls around trained them to concentrate and be more aware of each other; another example is ‘mirrors’, where one learner reproduces the movements of a partner standing opposite. This improves physical coordination as well as collaborative skills (Maley & Duff, 2005; Fontichiaro, 2007). The young learners were introduced to the notion of the occupation of space: how to move in relation to others, awareness of being on stage and not turning one’s back on the audience.

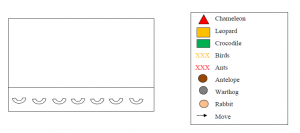

- Rehearse stage interactions with other characters. Encounters between the different characters were imagined by creating tableaux in small groups or through improvisation of the different scenes of the story. We provided a script as, for this first venture into drama, the young learners were unable to invent their dialogues. We also gave them outlines of a stage, showing the separation between stage and audience, as well as a key of the different characters so that they could work out the movements for each scene (see Figure 6). [End of Page 24]

- Consider costumes and props. No costumes were used and the only prop required was a rope for Crafty Chameleon. The class staging A Bit Lost made masks for their characters, but these turned out to be more of a distraction than an aid. The young learners had done preparation work on becoming their animals, using voice and body language, so that the audience entirely understood the characters even when they did not understand all the language.

- Design language tasks. Simple written exercises were designed to complete the language work and help consolidate language acquisition, in accordance with French curricula guidelines, which require a writing exercise (trace écrite) to complete each unit.

- Set aside time for discussion in the majority language. Time was set aside for answering questions and dealing with problems, explaining and discussing certain aspects of the language in the mother tongue. The young learners knew that these times would occur so they could immerse themselves as much as possible in the foreign language experience during the classes.

Figure 6. Layout of stage and key to characters for blocking the movements of a scene

Findings

The answers to the questionnaire completed by the pupils showed that they had greatly enjoyed the language classes (see Table 2): 74 per cent said they had ‘loved’ the drama [End of Page 25] project, 15.5 per cent had ‘liked’ it and none ticked the two choices ‘not liked’ and ‘not liked at all’. One young learner said that despite having enjoyed the classes, (s)he had not learned any new language (so wouldn’t like to do it again) and another said (s)he wasn’t sure whether (s)he would like to do drama again (see Table 3). The comments made by the 37 others were very positive, for example ‘I adored these language classes’ (‘j’ai adoré faire les langues’) and ‘I liked learning the animals’ (‘j’ai aimé quand on apprenait les animaux’). What they enjoyed was the newness of the approach and the fact that they were able to move about and act out the language. A large majority declared it easier to learn the language with this approach.

| I loved it | I liked it | I didn’t like it so much | I didn’t like it at all |

| 29 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2. Did you like doing drama in your language class?

| Yes | I don’t know | No |

| 37 | 1 | 1 |

Table 3. Would you like to do drama again?

In reply to the question about what could be changed or improved if they were to do drama again, 16 answered that they would change nothing – it was great as it was. Seven made suggestions related to the story: choose one with more humour, a longer one or one with more characters; seven said they would change something to do with the performance: start the drama classes earlier so they could do more, learn the dialogues better or improve their acting, and seven gave no response. The performance took place in in the courtyard on the last day of school, in front of all the teachers and children.

The teachers found the classes tiring, especially since they came at the end of the school year, but very productive and they would definitely do them again the following year. Having thought that it might be too linguistically challenging for the young learners to acquire all the vocabulary necessary to learn the dialogues, they were pleasantly surprised by the ability of the children to memorize their lines while embodying their characters and mastering the movements. The first few classes were slowed down by a [End of Page 26] certain difficulty to recall vocabulary which the teachers thought had already been learned during the year, but as the pupils grew accustomed to the format of the drama classes, the speed picked up and they became more autonomous in their group work and more responsible for their learning process.

The teachers were afraid that the pupils would become bored with the work on the animals, their emotions and actions, but as the children realized that the end result would be a performance, they eagerly looked forward to the sessions and wanted to rehearse more and improve. Since it was the first time these teachers had tried drama with their classes, they were understandably nervous about the overflow of energy, particularly from the older boys. With each progressive visit, we saw the young learners become more enthusiastic and expressive, happy to greet in English and reply confidently. The teachers noticed that they were speaking the foreign language more spontaneously than before the drama classes. Having been somewhat dubious to begin with and during the first couple of classes, both teachers observed a growing investment in the process and were convinced by the end results.

Conclusion

Our project allowed us to test our premise and go some way toward verifying the positive effect of drama through picturebooks in the foreign language class. The picturebooks, and particularly their illustrations, provide the impetus or ‘stage directions’ as to how the animals feel, act and speak. We confirmed the enjoyment and motivation of this approach for the young learners, and they and the teachers found the language class more dynamic. We were not able to test the children’s linguistic performance so we only have the observations of their teachers stating that the oral communication ability improved. We regret that the pupils were not able to create their own dialogues in this first exploration and in the relatively limited time available, but remain convinced that with exposure to drama over a longer period, the learners would become more creative with the foreign language.

We wish to stress the need to train and reassure teachers with regard to including drama in their classes. In the EFL with young learners context, Bland similarly argues that drama ‘must be introduced and rehearsed in teacher education in order to attain widespread [End of Page 27] application in schools’ (2014: 156). Many teachers are afraid to try drama as it entails risk taking on several levels: the teachers must venture to use an approach where the young learners must dare to act in front of others. The novelty of the drama techniques may make the initial classes difficult as young learners are so used to being told to sit still and listen. The teacher has to participate to some extent, sometimes even becoming the narrator or taking a role, so the teacher/pupil relationship is modified by this approach. The two teachers with whom we worked are going to repeat the units with their new classes, introducing the drama techniques earlier in the year, and others are interested in trying out this approach. After three years of researching and working on drama, we now find it hard to conceive of a language class where the learners are static and not embodying and living the language they are learning.

Notes

1. The French foreign language curriculum for primary school: http://www.education.gouv.fr/bo/2007/hs8/default.htm

2. We are very grateful to Carole Boussard and Annie Chourau of l’Ecole Maurice Bécanne for their valuable collaboration on this project.

Bibliography

Donaldson, J. (2008). The Gruffalo Pop-Up Theatre Book. Scheffler, A. (Illus.) London: Macmillan Children’s Books.

Fitzpatrick, M.-L. (2000). Izzy and Skunk. London: Gullane Children’s Books.

Hadithi, M. (1987). Crafty Chameleon. Kennaway, A. (Illus.) London: Hodder Children’s Books.

Haughton, C. (2010). A Bit Lost. London: Walker Children’s Books.

Moodie, F. (2002). Noko and the Night Monster. London: Frances Lincoln.

Nicoll, H. (1976). Meg’s Eggs. Pienowski, J. (Illus.) London: Puffin Books.

Ruzzier, S. (2008). Amandina. New York: Roaring Book Press.

Sáez Castán, J. (2003). Los Tres Erizos. Caracas: Ekaré. [End of Page 28]

Sendak, M. (1963) Where the Wild Things Are. New York: HarperCollins.

Willis, J. (2009). Big Bad Bun. Ross, T. (Illus.) London: Anderson Press.

References

Audin, L. (2003). L’apprentissage d’une langue étrangère à l’école primaire: quel(s) enseignement(s) en tirer? Les Langues Modernes, 3, 10-19.

Bernanoce, M. (2007). L’album-théâtre? Un genre en cours de constitution. In H. Gondrand & J-F. Massol (Eds.), Textes et images dans l’album et la bande dessinée pour enfants. Grenoble: CRDP (Les cahiers de Lire écrire à l’école), pp. 121-133.

Bland, J. (2014). Interactive theatre with student teachers and young learners: Enhancing EFL learning across institutional divisions in Germany. In S. Rich (Ed.), International Perspectives on Teaching English to Young Leaners. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 156-174.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available at: http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/source/framework_en.pdf

Ellis, G. & Brewster, J. (2002). Tell it Again! The New Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Fontichiaro, K. (2007). Active Learning Through Drama, Podcasting and Puppetry. Grades K-8. Westport: Libraries Unlimited.

Maley, A. & Duff, A. (2005). Drama Techniques. A Resource Book of Communication Activities for Language Teachers. (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mourão, S. (2013). Picturebook: Object of discovery. In J. Bland & C. Lütge (Eds.), Children’s Literature in Second Language Education. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 71-84.

Nières, I. (1991). Le théâtre est un jeu d’enfant. In J. Perrot (Ed.), Jeux graphiques dans l’album pour la jeunesse. Créteil: CRDP, Université Paris-Nord, pp. 29-38.

Peirce, C.S. (1998). The Essential Peirce, Selected Philosophical Writings, Volume 2 (1893-1913), Peirce Edition Project, (Eds.), Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [End of Page 29]

Perrot, J. (1999). Jeux et enjeux du livre d’enfance et de jeunesse. Paris: Editions du Cercle de la Librairie.

Schmidt, P. (2006). Le théâtre comme art dans l’apprentissage de la langue étrangère. Spiral – Revue de Recherches en Éducation, 38, 93-109. Available at : http://spirale-edu-revue.fr/IMG/pdf/8_Schmidt_38F.pdf

Schmidt, P. (2010). Théâtre et langues vivantes en primaire, Langues Modernes, 2, 30-38.

Available at : http://www.aplv-languesmodernes.org/IMG/pdf/2010-2_schmidt.pdf

Van der Linden, S. (2005). L’album en liberté. In I. Nières-Chevrel, (Ed.), Littérature de jeunesse : incertaines frontières (Actes du colloque de Cerisy-La-Salle, 2004). Paris: Editions Gallimard Jeunesse.

Van der Linden, S. (2006). Lire l’album. Le Puy-en-Vellay: L’Atelier du Poisson Soluble. [End of Page 30]