| Azzi in Between – A Bilingual Experience in the Primary EFL Classroom

Grit Bergner |

Download PDF |

Abstract

The book Azzi in Between (Garland, 2012) provides the opportunity for presenting information on and encouraging understanding of the life of refugees and asylum seekers in the EFL classroom, despite being a challenging picturebook in linguistic terms for young foreign language learners. This paper describes how the content of the book was made accessible to a group of children aged 8 and 9 in Germany through a series of activities which relied upon the support of the classroom teacher to prepare and consolidate activities, thus using both English and German to help children understand and discuss the issues of refugee and asylum seekers.

Keywords: asylum seekers, refugees, visual literacy, vocabulary

Dr Grit Bergner is a senior lecturer in the Department of Language Learning and Language Teaching at the University of Erfurt. She worked as a primary school teacher for 25 years and is co-author of the course book Discovery (2015).

Introduction

According to the annual Global Trends report of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR, 2014, p. 2), at the end of the year 2014 nearly 60 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide. Due to conflict and persecution, about 42,500 individuals per day left their homes and sought protection elsewhere in 2014. More than half of them are children. Whether these children encounter a welcoming environment rather than reservation or isolation in the receiving country will partly depend upon the way these issues are discussed with children at local schools. Dolan (2014) suggests the book Azzi in Between (Garland, 2012) as a starting point for helping school children understand why people [End of Page 44] become asylum seekers and the difficulties they face in a new country, for the story of Azzi, an asylum seeker, is told and structured in a child-appropriate way. However, it contains more than 500 headwords and the changes between different times and places might be a challenge for beginner language learners. According to Dolan (2014), A2 language level seems to be required for the understanding of this book’s message.

Nevertheless, for a number of very good reasons, this picturebook was selected and introduced to a group of 9 and 10 year olds in their second year of learning English. The topic is extremely important in the current situation in Europe and these children had showed concern and sought information about refugees and their plight. Azzi in Between describes the life of refugees from the perspective of a girl at primary school age in an informative, indeed touching way. The main character is of the same age as the learners, which makes her easy to empathise with. Listening to or reading the story in English is likely to challenge the learners, for they will need to remember previously learned words, to predict, and to make meaning from the combination of words and illustrations. The content of the book may provoke different opinions and questions, resulting in the children applying their English in meaningful communicative situations.

Since many of the children in this class had not reached A1 level at the time Azzi in Between was introduced, a variety of manageable tasks were created to help the children understand the story and its message.

Azzi in Between

‘There was a country at war, and that is where the story begins. It is the story of Azzi…’ (Garland, 2012, unpaginated). Having lived among refugee families, deeply moved by their memories and inspired by her experience with refugee children at the local school, Sarah Garland tells Azzi’s story – a story of anxiety and loss as well as of hope and newly discovered confidence. Azzi’s home is in an unnamed country. The reader may guess from the illustrations that the family is of Middle Eastern origin. Azzi and her parents have to flee from war and their long and frightening journey leads them to another country where Azzi has to learn a new language and start a new school. Kind teachers and classmates help her to learn English and she makes friends and gradually becomes more involved in the everyday life of this new community. [End of Page 45]

Azzi’s story is linked to the stories of several people who share her experience of having to leave home: her father, her grandmother, and Sabeen, who had stayed in a refugee camp for many years and who is now a helper at Azzi’s school. Certain objects also tell their stories of the flight: beans, which were brought from the old home, Grandma’s blanket as a symbol of home and warmth and, of course, Azzi’s teddy bear, whose story can be followed by looking carefully at the illustrations.

The author decided to give the book the format of a graphic novel, in order for it ‘to appeal to as wide an age range as possible’ (Toft, 2013). Simple sentences but rich vocabulary accompany each panel. Occasionally, speech bubbles complete the picture of the situation. The illustrations are clear line drawings, coloured with artist’s felt tip pens and watercolour. While bright, warm colours represent home and happiness, war, danger and anxiety are depicted in grey and black. These help the young reader to understand the main idea of the story and the strong expressions and carefully drawn details may also contribute to the development of visual literacy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Reading time [End of Page 46]

The Classroom Situation

The book was introduced to a group of grade 4 children (aged 8 and 9 years old) in a small town in Thuringia, Germany in spring 2014. At that time, none of the children had had any experience of refugees and their knowledge of the topic was limited to isolated facts from the news or overheard opinions of adults.

All of the children, eleven girls and nine boys, were native speakers of German. They had been learning English for about one-and-a-half years, in two 45-minute lessons per week, a total of one hundred lessons. The children’s listening skills were at or below A1 level. They were able to understand classroom phrases in English as well as very simple everyday expressions in clear and slow speech. However, they were used to reading English picturebooks together with their English teacher. The topics of family, jobs, houses and homes as well as feelings had been covered before the book was presented. Yet the number of productively used English words was still limited to not more than 200-300. In their communication, the children mainly used fixed phrases and language patterns which were individualised by adding single words of personal relevance.

The topic of refugees is closely related to the topic of children’s rights, which is part of the Thuringian social studies syllabus (TMBWK, 2010a), and thus the unit of work around Azzi in Between was planned together with the class teacher. Four lessons of English were framed by two lessons of social studies before and one lesson after the book had been read. As such the story could be contextualised and related to the children’s personal experience in their mother tongue during the social studies lessons, while the English lessons focused on the picturebook and the development of certain language skills. During social studies lessons, the learners discussed the human rights of children and the situation of children in different countries around the world. The learners were asked to think about why children are displaced and what might happen to them in the new country. They completed two sentences in German: ‘Children have to leave their home because…’ and ‘Arriving in a foreign country …’. The learners’ thoughts were collected in class and supplemented by photographs from newspapers and magazines. Different opinions and attitudes concerning the topic emerged during the discussion and the following are examples: [End of Page 47]

Children have to leave their country because… ‘it’s dangerous’, ‘they are scared’, ‘their houses are destroyed because of war’.

Arriving in the foreign country… ‘they are happy to find shelter’; ‘they have to get used to everything and to learn a new language’; ‘they are offended’; ‘some people don’t want to have them there’. [Translated by author]

Aims

Dolan (2014, p. 94) points out that multicultural literature can serve the dual function of providing opportunities for language development and enabling an appreciation of social justice issues. According to the Thuringian syllabus for foreign languages in primary schools (TMBWK, 2010b), the language aims were:

- Listening: Learners are able to understand the gist of the story. They can derive the probable meaning of unknown words from the context, e.g. pictures, mime and gestures of the storyteller.

- Speaking: They can establish basic social contact by using simple forms of greetings. Based on given language patterns, they can answer questions about themselves, their homes and families and perform short dialogues. They can describe illustrations and name feelings of the main characters.

- Reading: Learners recognise familiar names, words and basic phrases. They identify keywords and link written words to details of the illustrations.

- Writing: Learners can copy single words and chunks from a wordlist and fill in gaps in a simple dialogue text.

- Mediation: The learners are able to summarise the main ideas of the story and to explain their thoughts in their mother tongue.

No given syllabus or word list is provided; instead, learners decide themselves what they would like to learn depending on what is of relevance to them.

Dealing with a picturebook slightly beyond their actual level of proficiency was going to be a challenge, but it was hoped that this would strengthen the learners’ learning [End of Page 48] skills and cognitive strategies, such as hypothesising and predicting. They were encouraged to use visual aids and dictionaries, to compare and to ask questions in order to understand the story. Besides this, the activities were designed to develop the learners’ social competence through working with partners or in groups.

Introduced in a predominantly mono-ethnic school, it was hoped that Azzi In Between might also help to develop the learners’ intercultural competence, learning about the topic of refugees as an issue of global relevance. It was intended to develop their empathy and understanding, recognising that ‘refugee children are ordinary children in extraordinary circumstances’ (Hope, 2008, p. 298).

Planning the story-based lessons

Due to its complexity, the story was divided into four parts:

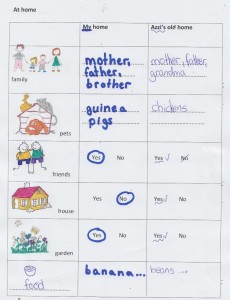

The first part of the book describes Azzi’s home, her everyday life and why her family had to flee. Many of the key words were already known to the learners, but the illustrations [End of Page 49] supported their understanding and the beginning of the verbal narrative was easily understood. Comparing Azzi’s old home to their own, the learners found that there were many similarities: living with mum and/or dad, going to school, playing with friends, having pets. When the children did not know the appropriate English word or expression to share this information, they inserted English words into German sentences, e.g. ‘Sie hat hens’. The English teacher recast into English, praising and correcting at the same time: ‘Yes, she’s got hens’. The findings were visualised in a table (Figure 2). Filling the gaps, the learners used vocabulary from the word lists in their textbooks or asked for help with words they did not know. The results were summarised in a plenary session in class. Encouraged by the teacher, the children also tried to form sentences in the target language: ‘I live with my mother, father and sister. Azzi lives with her mother, father and grandma’. ‘I like bananas. Azzi likes beans’.

Figure 2: Similarities between Azzi’s and the children’s homes [End of Page 50]

Azzi’s life changes dramatically when her father receives a warning they have to leave their home. In a hurry, Azzi grabs her teddy bear, the only toy she can take with her on the journey, and much to Azzi’s distress, her grandmother stays at home to look after the house. She knows she will badly miss her Grandma. While reading this part, the learners seemed to sympathise with Azzi. They were asked what they would take with them if they had to choose one single item for such a journey. Most of the children wanted to give an opinion, although it was a hard decision as well as a difficult task from a linguistic perspective. To encourage as many children as possible to speak, one- or two-word utterances like ‘mummy’ or ‘my dog’ were accepted.

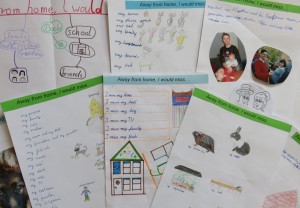

Having accompanied Azzi on her dangerous journey to a new country, the learners understood that Azzi was relieved and sad at the same time when she finally arrived at her new home. They thought about what they would miss if they were far away from their home. A paper strip which said, ‘Away from home, I would miss…’ was the starting point for the making of collages.

Figure 3: Collages made by the learners

The children collected all their ideas, drew pictures and wrote down short phrases or sentences. Many children had shared what they were doing with their families at home and parents helped with photographs or the spelling of new words. Finally, when the [End of Page 51] children presented their collages, they used words they knew from their English lessons like ‘family’, ‘friends’, ‘pet’ or ‘bedroom’, as well as recently learned words which seemed to be important within their individual contexts like ‘trampoline’, ‘fish tank’ or ‘tree house’ (Figure 4).

Part 2: A new school

As stated by Ellis and Brewster (2014, p. 14): ‘…it is very important to develop children’s visual literacy because providing information through visual images is an important means of communication in the global world’. To find out how Azzi’s story continues, the children were given single illustrations from the book together with the accompanying sentences. At first, the children were asked to make meaning from the short text and the illustrations individually. Having underlined the words they already knew, they were allowed to look up key words in a dictionary. Afterwards, the children came together in groups, based on the coloured dots on their copies. They discussed how their pictures might belong together and tried to put them into a meaningful order (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Discussing the right order of the pictures

As necessary, the children were guided by the teacher to link details of the illustration to the text. Presenting their findings in class, the children gave reasons for their decisions and compared their solutions. Children had to explain different points of view and to [End of Page 52] predict what might come next. In such a situation, use of the mother tongue is quite natural (Ellis & Brewster, 2014, p. 21). Insisting on the use of English would have discouraged the learners. Finally, that part of the story was read out from the book in order to summarise and to return to English.

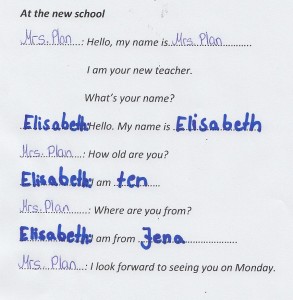

At her new school, Azzi is welcomed by her new teacher, and although the teacher is a warm-hearted person, Azzi is still very shy, because she doesn’t really understand what the teacher says. Putting themselves in Azzi’s shoes was not too difficult for the learners, since their command of the foreign language was equally limited. Based on a passage from the book, they practised short dialogues. The learners worked in pairs – one playing the teacher while the other played herself – pretending to be new in the class. The dialogue was first prepared as a gap-filling activity (see Figure 5), then read out, or, depending on the self-confidence of the children, acted out in front of the class.

Figure 5: Dialogue prepared in pair work

Part 3: Azzi’s new home

Step by step, Azzi’s and her family’s life improve. The arrival of Grandma makes them all happy and helps them to become accustomed to their new environment. At this point in the story, children were asked to summarise what had happened so far from two different points of view. First, they discussed how Azzi’s feelings had changed. Feelings are rarely named in the book but shown in the illustrations using colour, expression and body [End of Page 53] posture. Reading the sentence ‘Azzi was thinking of Grandma’ and seeing her facial expression in the picture above, the reader can conclude that Azzi is sad. So the children once again had to combine both reading and visual skills in order to be able to say whether Azzi was happy, sad, scared or excited in a specific situation. Eventually, the children agreed that after all of these emotional ups and downs, positive feelings were predominant. Then the children were guided to have a closer look at the use of colour in the book. They soon detected the visual message: grey and black stand for sadness, fear and war and brighter colours symbolise peace and happiness. Throughout the book, colours turn from dark to bright, and the final pages, which are in warm brown, green and yellow, indicate an optimistic perspective for the family in their new home.

Part 4: The story of the beans

Beans are the main ingredient in Azzi’s favourite meal, ‘spicy beans’, which is prepared by her mother in the story. While her father has given up the dream of growing beans in the new country, Azzi suggests sowing them in the school garden. Coming home in high spirits to share her idea, Azzi discovers that mother is cooking supper from the bean seeds she had hoped to plant. Listening to that part of the story, the learners seemed to share Azzi’s feelings of excitement and disappointment, and finally rejoiced together with her when she spotted the eight beans that had fallen from father’s bag. The learners discovered that the story of the beans is very similar to that of Azzi’s family: uprooted from their home, brought to a foreign country, and finally taking root in a new soil. In addition, the children were interested in a very practical question: what was actually meant by ‘spicy beans’? Having translated the phrase literally, it was supposed that the meal might be a kind of chilli con carne, a spicy dish which most of them knew and which usually contains kidney beans. So the children planted kidney beans to see if they would grow in their classroom. They planted kidney beans, bought at the local supermarket, in soil in plastic cups and watered them – and the plants grew and grew (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Follow-up activity: growing beans

A roundup: the children’s responses

In a round-up session, the children were asked what they thought to be important about the story. At that point, the teacher was more interested in what they wanted to say than what they were able to say in English. Therefore, they were allowed to give their opinions in German, anonymously. In total, 38 different statements were made. Seven children liked the story of the beans and six children seemed to be especially touched by Grandma’s story. Six children stated it had been important to discuss the topic in general and some children even wrote that it was good to learn about the difficult lives of refugees and the dangers of war. Five children liked the idea that Azzi’s family found a new home. Compared to the number of comments on the content of the story, only a few learners referred to the language learning benefit. Three children mentioned they liked that the story was written in English and that they had learned new words, and finally, one child [End of Page 55] wrote that they had felt disturbed by the interruptions ‘when we had to practise something’. This could be taken as advice for the teacher snot to spoil the magic of a story with too many additional tasks.

The children were also asked to think about questions they would like to ask Azzi. Many children asked general questions, such as ‘How does the story go on?’ One learner, possibly aware of the commercialisation of children’s literature, asked: ‘Are there more Azzi books?’ Some were interested in practical aspects of Azzi’s life, e.g. ‘Do you have more toys than just one teddy bear?’ or ‘Have you mastered the new language by now?’ or ‘Do you have a boyfriend?’ Some questions indicated that children shared Azzi’s feelings: ‘Do you still miss your old home?’, ‘Do you like the new country?’ Even philosophical questions were raised: ‘How would you describe the difference between war and peace?’ or ‘Do you think it would have been better to leave the country earlier?’ Spontaneously, the children spoke German. But with the guidance of the teacher, they found that they were able to ask some of the questions in English: ‘How old are you?’, ‘Do you like the food here?’, ‘Are you happy?’

The story had become personally relevant to the learners, and depending on their developmental stage and their knowledge of the world, different aspects were important. All of them appeared to have gained insights into the topic and seemed to have developed empathy with refugees. From the point of view of the learners, the target language was a medium of storytelling rather than an object of learning.

Figure 7: Children’s comments and questions [End of Page 56]

Summary

Azzi in Between tells the story of a refugee child in a realistic way that shows no horror, and it was made accessible to young learners of English through a variety of activities. The language focus in this project was on vocabulary sets and phrases the learners needed to understand the main ideas of the story and which would be useful for them to utilise in everyday life. Using the children’s mother tongue helped to clarify the context of the book and to summarise parts of the story – in this way the learners’ attention was maintained. English was spoken as much as possible and German used only if necessary. The picturebook format supported the development of the learners’ visual literacy and empathy, and understanding for the situation of refugees was facilitated by highlighting specific features of the book, such as the use of colour, symbols and details of the illustrations. In addition, comparing Azzi’s situation to the learners’ own lives may have helped them accept differences and realise the similarities between all children in the world. Working in collaboration with the classroom teacher enabled a deeper discussion around the topic and supported a greater variety of activities.

Bibliography

Garland, S. (2012). Azzi in Between. London: Francis Lincoln Children’s Books.

References

Brewster, J. & Ellis, G. (2014). Tell it Again! The Storytelling Handbook for Primary English Language Teachers. London: British Council. Retrieved from http://englishagenda.britishcouncil.org/sites/ec/files/D467_Storytelling_handbook_FINAL_web.pdf

Dolan, A. (2014). Intercultural education, picturebooks and refugees: Approaches for language teachers. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 2(1), 92-109.

Hope, J. (2008). ‘One day we had to run’: The development of the refugee identity in children’s literature and its function in education. Children’s Literature in Education, 39(4), 295-304. [End of Page 57]

TMBWK (2010a). Lehrplan für die Grundschule und für die Förderschule mit dem Bildungsgang der Grundschule Ethik. Erfurt: Thüringer Ministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur. Retrieved from http://www.schulportal-thueringen.de/web/guest/media/detail?tspi=1270

TMBWK (2010b). Lehrplan für die Grundschule und für die Förderschule mit dem Bildungsgang der Grundschule Fremdsprache. Erfurt: Thüringer Ministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur. Retrieved from http://www.schulportal-thueringen.de/web/guest/media/detail?tspi=1263

Toft, Z. (2013). An interview with Sarah Garland. Playing by the book, 18 June. Retrieved from http://www.playingbythebook.net/2013/06/18/an-interview-with-sarah-garland/

UNHCR (2014). World at War. UNHCR Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2014. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/556725e69.html [End of Page 58]