| Promoting ‘Learning’ Literacy through Picturebooks: Learning How to Learn

Gail Ellis |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Picturebooks provide a rich and motivating resource to develop children’s early language learning such as basic understanding, vocabulary and phrases related to the content of a story, but they can also be used to develop multiple literacies. These include visual, emotional, cultural, nature, digital, moving image literacy and ‘learning’ literacy, which is linked to learning how to learn and learner autonomy. ‘Learning’ literacy is described as an ethos, a culture and a way of life and involves being ready to develop learning capacities and the behaviours individuals need, including being willing to learn continuously, as competencies essential to thriving in a globally connected, digitally driven world. The Important Book (Brown & Weisgard, 1949) is used as an example of how learning literacy can be integrated into primary English language pedagogy by applying the Plan, Do, Review model of reflection. Working through the three stages of the Plan Do Review cycle, children are informed of the aims of the activity; they identify success criteria, draft and refine their own paragraphs about an important object, review what they did, what they learnt and how they learnt and then assess their performance to identify next steps. This process enables the teacher to create learning environments that develop learning literacy, by providing opportunities for systematic reflection and experimentation and the development of metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies.

Keywords: Picturebooks, multiple literacies, learning how to learn, metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies, reflection, primary English language pedagogy

Gail Ellis is Adviser Young Learners and Quality for the British Council and based in Paris. Her publications include Learning to Learn English, The Primary English Teacher’s Guide, Tell it Again! and Teaching children how to learn. Her main interests are children’s literature, young learner ELT management and inclusive education. [End of Page 27]

Introduction

I began using picturebooks as my main teaching resource in state primary schools in Paris in 1989, as they provide a rich, motivating and authentic source of meaningful input to develop children’s early English language learning. However, I soon realised they can be used to develop much more than children’s basic understanding, vocabulary and phrases related to the content of a story. They can also be used to help children develop other ways of interpreting, understanding and making meaning, since picturebooks lend themselves to developing multiple literacies.

The term multiple literacies extends the traditional view of literacy, often referred to as functional literacy, which is the ability to read and write. It focuses beyond alphabetical representations and brings into the classroom multimodal resources, as well as those typical of the new, digital media. Meaning is made in ways that are increasingly multimodal in which written-linguistic modes of meaning interface with oral, visual, audio, gestural, tactile and spatial patterns of meaning, to include the interpretation and understanding of information presented via different modes.

Multiple literacies encompass many forms of literacy that require learning how to interpret and decode information conveyed through multiple modes. For example, information conveyed through visual images is an important means of communication, so helping children interpret and understand illustrations in a picturebook develops their visual literacy. Interpreting and understanding facial expressions, gestures and body language helps children develop emotional literacy. Interpreting and understanding similarities and differences between the culture depicted in a picturebook and the child’s own cultural reality helps them develop cultural literacy. Interpreting and understanding the natural world as depicted in a picturebook helps children develop nature literacy. Interpreting and understanding information conveyed through different digital modes integrated into activities to complement learning around a picturebook helps children develop digital literacy. Using animations of picturebooks helps children develop moving image literacy.

We can see that the term multiple literacies embraces the notion that there are multiple ‘modes of representation’ which are much broader than language alone (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000, p. 5). Multiple literacies pedagogy ‘encourages a broader perspective of [End of Page 28] the student as a learner and values diverse ways of knowing, thinking, doing and being’ (O’Rourke, 2005, p. 10). It is underpinned by multimodal theory, which asserts that children create meaning using a ‘multiplicity of modes, means and materials’ for self-expression’ (Kress, 1997, p. 97).

In the early years and primary language classroom, this involves acknowledging and recognising children’s drawings, constructions, arts and crafts and actions as alternative ways of communicating with the teacher about their world in a foreign language. It also invites the teacher to use multimodal input and resources. Using picturebooks allows the teacher to provide multimodal input as they offer a springboard for a range of associated activities, such as songs and chants, realia, film, actions and drama, and digital technologies. These enable children to make meaning, develop and extend language.

Multilple literacies and The Snowman

One of the first picturebooks I used with a class of 9-year-olds was Raymond Briggs’ The Snowman (1978), a wordless picturebook, as I was sure the children would be enchanted by the story and images, given their limited English. They would be able to ‘read’ the pictures and construct their own meaning and find their own words to shape the story. I found the children were more aware of their contribution in making the pictures tell a story as they entered into a partnership with the illustrator. A wordless picturebook offers an open invitation where personal interpretation counts rather than finding a right or wrong answer, and they promote a sense of power, creativity and freedom. The Snowman enabled the children to exercise their imaginations and to become personally, actively and creatively involved in the story as they identified with the characters. It also coincided with the type of weather formally typical of November and December in parts of Europe, and it provided potential for Christmas-related activities.

After the first lessons, I soon realised that children were developing much more than vocabulary and phrases related to colours, clothes, parts of the body, the weather, etc. As they interpreted the picture narrative, they were developing their visual literacy. They were developing emotional literacy as they interpreted the gestures and facial expressions in the illustrations, which enabled them to empathise with the boy in the story, especially in [End of Page 29] the final illustration where the boy is looking down on a pile of melted snow. As one child said: ‘The Snowman story makes me cry. I don’t want him to melt. I don’t want the story to end’. For children to cry at the end of The Snowman shows they have come to empathise with a distinctive and believable character. The children were aware that the Snowman was the boy’s dream or fantasy, which enabled them to explain their sorrow at the end of the story – it was not only the melting snowman but also the end of the boy’s dream.

They were also developing cultural literacy as they noticed details about the setting or how the characters greeted each other, and made comparisons with their own culture; and nature literacy, as they learnt about winter weather, snow and how snowflakes are formed. Creative Writer (Microsoft Kids, 1994) was used to develop digital literacy as children created Snowman menus, and the accompanying film of The Snowman was used to develop moving image literacy. I also realised that children were developing ‘learning’ literacy as they sought clues to meaning via the illustrations, predicted what was going to happen next, organised their learning materials and reviewed their learning.

‘Learning’ Literacy

‘Learning’ literacy is a relatively new term and is linked to learning how to learn and to learner autonomy. It involves developing awareness and understanding of one’s own learning processes, personal preferences and learning strategies. In her blog posting entitled The Global Search for Education: Learning How to Learn (20.01.2016), Rubin describes learning literacy as follows: ‘Being ready to develop our own learning capacities, being able to develop the behaviors we now need as individuals, including being willing to learn continuously, are competencies essential to thriving in a globally connected, digitally driven world’. Rubin’s interviewee, Jim Wynn, co-founder of EducationFastForward offers this definition: ‘Learning literacy is an ethos, a culture and a way of life’. Moreover, learning literary is also about developing an inquisitive mindset and using resources that ignite curiosity and enable experimentation.

Learning literacy is an important aim of most curricula throughout the world, since it underpins learning in all areas of the curriculum and life, and is one of the EU’s eight key competencies for lifelong learning (EU, 2006). It is an important aspect of a child’s overall educational development from a very early age. As Tina Bruce (2011, p. 47) states: [End of Page 30] ‘Children learn best when they are given appropriate responsibility, allowed to make errors, decisions and choices, and respected as autonomous learners’. The Early Years Foundation Stage Profile 2017 Handbook (Standards & Testing Agency, 2016, p. 13) states: ‘Practitioners should involve children fully in their own assessment by encouraging them to communicate about and review their own learning’, since even very young children do possess a considerable degree of metacognitive knowledge and ability (Nisbet & Shucksmith, 1986; Whitebread, Coltman, Anderson, Mehta & Pasternak, 2005).

Children’s ability to reflect on and talk about their learning should not be underestimated. They are competent, insightful and spontaneous commentators on their own learning experiences if they are given the opportunity to do so. So picturebooks can provide an ideal resource to develop children’s language learning as well as their learning literacy, and instil the ethos expressed by Wynn (see Rubin, 2016).

Developing ‘Learning’ Literacy with Picturebooks

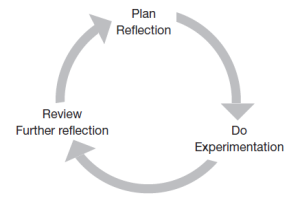

Learning literacy can be integrated into a story-based approach with children where between six and twelve hours are spent on a picturebook (Ellis & Brewster, 2014) by applying the Plan Do Review model of reflection. For a list of picturebook titles suitable for English language learning, see Wilbur’s storybook recommendations (Ellis & Ibrahim, 2015a). The Plan Do Review model originates from the HighScope approach to early childhood education (Hohmann, Epstein & Weikart, 2008), which is a child-initiated approach to learning. It provides a consistent, predictable routine that structures the learning sequence and gives children a sense of control over what happens next, and contributes to a stable and secure emotional environment within which they are free to make choices and initiate activities.

The Plan Do Review model of reflection consists of three stages that can be applied to an overall scheme of work around a picturebook where we use the familiar pre- while- and post-storytelling activities. It can also be applied to each lesson and to each activity. This model provides opportunities for systematic reflection, experimentation and further reflection, thereby developing both metacognitive and cognitive learning strategies (O’Malley, Chamot, Stewner-Manzanares, Kupper & Russo, 1985). Metacognitive strategies are strategies that involve children in reflecting on their learning in order to plan, [End of Page 31] monitor and evaluate their learning. Cognitive strategies are task-specific and involve children in doing things or experimenting with the language and their learning material and relate to the skills areas.

Children usually get a lot of implicit practice in developing cognitive strategies as the requirement for the use of a particular strategy is embedded within the activities. Examples are sorting or classifying, listening for specific information, predicting and sequencing. But most classroom situations or materials rarely inform children explicitly about the strategies they are using and why, and they are not encouraged to reflect on their learning. In other words, the metacognitive dimension is missing. So in order to develop learning literacy the teacher needs to take on an expanded role and incorporate this missing metacognitive dimension into her lessons.

Developing ‘Learning’ Literacy with The Important Book

I discovered Margaret Wise Brown’s The Important Book (1949, illustrated Leonard Weisgard) only relatively recently (see Recommended Reads, CLELEjournal, 4/1, 2016 http://clelejournal.org/recommended-reads-may-2016/). Each double spread is illustrated alternately in black-and-white and then colour and dedicated to an everyday object. The illustrations have a slightly surreal feel to them. A poetic paragraph describes the major attributes of each object, such as a spoon, a daisy, the rain, grass, snow, an apple, the wind, the sky, and a shoe. Each paragraph begins and ends with the key attribute, adding repetition. For example: ‘The important thing about a spoon is that you eat with it. It’s like a little shovel, you hold it in your hand, you can put it in your mouth, it isn’t flat, it’s hollow, and it spoons things up. But the important thing about a spoon is that you eat with [End of Page 32] it’ (Brown & Weisgard, 1949: np). The rhythmic paragraphs assign a dream-like quality to reality, ‘the important thing about a daisy is that it is white’, ‘the important thing about the sky is that it is always there’ and ‘the important thing about glass is that you can see through it’.

The format of the book provides children with a perfect model for how to write a good paragraph, with a topic sentence and supporting sentences about an object of their own choice. The book encourages creating and thinking critically as it invites children to construct their own opinions about everyday things in their diverse social and cultural contexts. It also provokes discussion as peers may or may not agree with the key attribute assigned to an object. The Important Book is a timeless book, it encourages children to look at things in different ways, consider multiple perspectives and opinions of their classmates and value everyday things.

The Important Book can be read aloud by the teacher and understood and enjoyed by younger children because there is plenty of repetition, a predictable pattern and simple, clear sentences and visual support. Older children can read the book independently as the illustrations and text interact to create meaning. I have used the book with a group of 9-year-olds who have had three years of English. I introduced the book by showing the cover and asking children to say what they thought was important about some of the things they could see, for example, an apple, water, glass, the sky, a butterfly, a cloud, asking them to begin, ‘The important thing about an apple is ………’ I then read the picturebook aloud, showing the illustrations and encouraging prediction as appropriate. I elicited how the paragraphs were organised, for example,

- The paragraphs start with a topic sentence stating the main important thing.

- There are supporting sentences describing the object and giving details three times.

- The final sentence repeats the main important thing.

As a follow-up activity, the children wrote a paragraph about an object of their own choice.

Plan Do Review model: Plan stage. The children were informed of the learning aims: ‘We’re going to learn how to write a paragraph with a topic sentence and supporting sentences.’ I integrated an assessment for learning approach (Black and Wiliam, 1998), and [End of Page 33] negotiated the success criteria with the children. Success criteria are the parts of the learning activity that are essential in achieving the learning aims. For example,

- Identify the pattern in the paragraph

- Use the pattern to structure your own paragraph.

- Use a dictionary or ask your teacher if necessary.

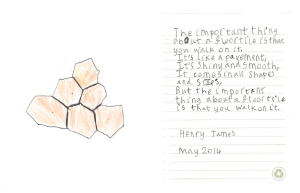

Plan Do Review model: Do stage. This stage involved children in producing their first draft of their paragraph, self- and peer-reviewing and editing until they were satisfied, and ready to produce and ‘publish’ their final version, see the example in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The important thing about a floor tile.

As a final outcome, the children collated their paragraphs into their own class ‘Important Book’, which they displayed in the story area of their classroom to return to and read during free-choice time.

Plan Do Review model: Review stage. Reviewing is an important aspect of the learning process, but this stage is often omitted from classroom practice. Reviewing can be used to work out how to improve a situation or learn from an experience. As John Dewey [End of Page 34] (1916) stressed, we do not learn from experience but from reflecting upon experience: ‘Such reflection upon experience gives rise to a distinction of what we experience (the experienced) and the experiencing – the ‘how’ (p. 196). Reviewing is important because it develops self-awareness and maximises and enhances learning time. This makes learning more efficient and effective as it improves the children’s understanding of their own learning processes so they can become better learners. The Plan Do Review model of reflection ensures that this important aspect of the learning process is not neglected.

The Review stage involved the children in reflecting on their learning in order to become aware of and understand their learning by responding to five reflection questions:

- What did you do?

- What did you learn?

- How did you learn?

- How well did you do?

- What do you need to do next?

Question one encouraged children to refer back to the success criteria and assess to what extent they followed these to complete the task. This helped them become more aware of the processes involved and what they needed to do to complete the task successfully. To make reviewing interesting and memorable, it was linked to the language and topic of the activity, which provided further consolidation and maintained the children’s interest and motivation. For example:

The important thing I did was …………………

The important thing I learnt was …………………

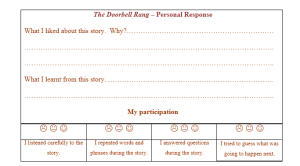

Question four encouraged children to assess their performance. Self-assessment is viewed as one of the pillars of learner autonomy (Harris, 1997). It can increase awareness of individual progress as it can help children locate their own strengths and weaknesses and get them to think about what they need to do next. Through self-assessment children understand that they each learn different things and each have their own preferences about content and learning. Children begin to look forward to this part of their learning and taking on responsibility for assessing how well they did and when what they say matters. Figure 2 shows how the self-assessment was linked to the content of the activity. Children [End of Page 35] chose a comment that best reflected how well they did and then completed the sentence in order to reflect further and personalise their self-assessment. Some chose to complete it in the style of The Important Book and wrote a paragraph. It is important that children discuss their self-assessment with their peers and their teacher to fully extend the potential for reflection, otherwise there is a risk that self-assessment may become a repetitive and mechanical task of ticking boxes, circling smiley faces or colouring traffic lights with no further reflection.

Figure 2: The Important Book – self-assessment (Ellis and Ibrahim, 2015b)

This reflection is important as it drives improvement in performance. However, it cannot be assumed that by reflecting, performance automatically improves. Children need to act upon their reflections and justify their self-assessment and discuss with their peers or their teacher. Action based upon reflection is critical, so question five involved children reflecting on what they needed to do next.

Thus learning literacy, in addition to English language learning, can be developed through picturebooks, if children are encouraged to plan and review their learning so they become aware of and understand the processes involved and of their own personal preferences and learning strategies.

Further Review Activities to Develop ‘Learning’ Literacy

There are many other ways children can reflect on their learning in a story-based approach and also give their personal response to a narrative. For example, they can complete a book mark by responding to questions about a story, drawing pictures about their favourite [End of Page 36] characters and illustrations, saying which part of the story they liked most and why, as well as evaluating their performance. Figure 3 on Pat Hutchins’ The Doorbell Rang (1986) demonstrates how children’s attention can be focussed on the learning strategies they used.

Figure 3: Personal response to a story

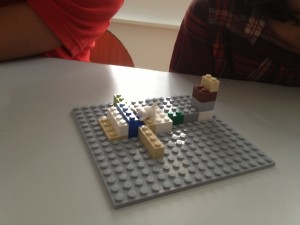

Figure 4 shows how children used Lego to construct a model of their favourite cat in Eve Sutton and Lynley Dodd’s picturebook, My Cat Likes to Hide in Boxes (1974), which involved them kinaesthetically and creatively in reflecting on their learning.

Figure 4: The cat from Spain flew an aeroplane [End of Page 37]

These techniques use a variety of modes so reviewing becomes multimodal – for example, drawing, photo and film, constructing models, movement and puppets. Reviewing is often considered a solitary activity, although it can be made interactive and collaborative by having children work in pairs or groups so they learn with and from each other. This can help develop social skills and creativity.

Conclusion

In order to develop learning literacy through picturebooks, teachers need to create a learning environment which provides opportunities for reflection, experimentation and further reflection. This can be achieved by applying the Plan Do Review model of reflection to both the overall scheme of work and to individual activities in a story-based approach. In this way, learning literacy can be systematically and explicitly developed through the combination of both metacognitive and cognitive strategy training. In addition, using multimodal resources makes learning inclusive by accommodating children’s learning differences and preferences, and enabling them to express their views and opinions about language learning in their preferred mode. Through doing so, children become more engaged in their English language learning as they gradually develop an awareness and understanding of their own learning processes. This equips children with the mindset required to learn new things in a rapidly diverse and changing world so learning literacy indeed becomes, as Wynn urges, ‘an ethos, a culture and a way of life’.

Bibliography

Briggs, R. (1978). The Snowman. Harmondsworth: Hamish Hamilton.

Brown, M.W. (1949). The Important Book. Leonard Weisgard (Illus.). New York: HarperCollins.

Hutchins, P. (1986). The Doorbell Rang. Harmondsworth: Puffin Books.

Sutton, E. (1974). My Cat Likes to Hide in Boxes. Lynley Dodd (Illus.). Harmondsworth: Puffin Books. [End of Page 38]

Black, P., Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139-148. http://weaeducation.typepad.co.uk/files/blackbox-1.pdf

Bruce, T. (2011). Early Childhood Education. 4th edition. London: Hodder Education.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2009). ‘Multiliteracies’: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal. 4, 164-195.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: The Macmillan Company. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Democracy_and_Education

Ellis, G. & Brewster, J. (2014). Tell it Again! The Storytelling Handbook for Primary English Language Teachers. London: British Council https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/D467_Storytelling_handbook_FINAL_web.pdf

Ellis, G. & Ibrahim, N. (2015a). Teachers’ toolkit. Wilbur’s storybook recommendations. Retrieved from http://www.deltapublishing.co.uk/content/uploads/2016/02/Wilburs-storybook-recommendations.pdf

Ellis, G. & Ibrahim, N. (2015b). Teaching Children How to Learn. Peaslake, Surrey: Delta Publishing.

EU. (2006). Key competences for lifelong learning – A European framework. Official Journal of the European Union, 30 December. http://www.alfa-trall.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/EU2007-keyCompetencesL3-brochure.pdf .

Harris, M. (1997). Self-assessment on language learning in formal setting. ELT Journal, 51(1), 12-14.

Hohmann, M., Epstein, A. S., & Weikart, D. (2008). Educating Young Children: Active Learning Practices for Preschool and Child Care Programs. 3rd Edition. Ypsilanti, MI: HighScope Press.

Kress, G. (1997). Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy. New York: Routledge.

Microsoft Kids. (1994). Creative Writer. Redmond, Washington: Microsoft Press.

Nisbet, J., & Shucksmith, J. (1986). Learning Strategies. Boston: Routledge.

O’Malley, J.M., Chamot, A., U., Stewner-Manzanares, G, Kupper, L. & Russo, R. P. [End of Page 39] (1985). Learning strategies used by beginning and intermediate ESLstudents. Language Learning, 35, 21-46.

O’Rourke, M. (2005). Multiliteracies for 21st Century Schools. Lindfield, NSW: The Australian National Schools Network Ltd.

Rubin, C. M. (2016, Jan 20). The global search for education: Learning how to learn. CMRubinWorld. Sustainable Solutions Through Global Discourse. Retrieved from http://www.cmrubinworld.com/the-global-search-for-education-learning-how-to-learn

Standards & Testing Agency (2016). Early Years Foundation Stage Profile 2017 Handbook. UK: Department for Education. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/564249/2017_EYFSP_handbook_v1.1.pdf

Whitebread, D., Coltman, P., Anderson, H., Mehta, S. & Pasternak, D.P. (2005). Metacognition in young children: Evidence from a naturalistic study of 3–5 year olds. Paper presented at the 5th Warwick International Early Years Conference, March 2005, and the 11th Biennial European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (EARLI) Conference, Cyprus, August 2005. https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/cindle/Cyprus%20paper%202.doc

[End of Page 40]