| Social Model Thinking about Disability through Picturebooks in Primary English

Gail Ellis |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Children with disabilities remain underrepresented in children’s picturebooks, so many children find they do not have characters that they can relate to. For some authors it may not occur to them to include a disabled character; or publishers may be reluctant to publish books about disability. When characters with disabilities are portrayed, they often reinforce society’s discomfort with disability by representing this as something to be overcome and tolerated, rather than challenging the realities of a disabling society. This paper identifies two types of literature, inclusion and immersive, that provide different representations of disability, as depicted in Susan Laughs (Willis & Ross, 1999) and Amazing (Antony, 2019a). The paper also shows how children in the Primary English Language Teaching (PELT) classroom can develop social awareness of disability by introducing the concept of the social model of disability in an age-appropriate way using Winnie the Witch (Thomas & Paul, 1987). Two further picturebooks, Perfectly Norman (Percival, 2017) and Kind (Green, 2019) are briefly discussed. Criteria are provided to enable educators to critically examine, select and use picturebooks which reflect qualitative representation of disability, and encourage meaningful discussion about inclusion when mediated by the educator from a critical disability studies lens. By encouraging social model thinking through picturebooks in the PELT classroom, teachers can embrace their wider professional remit by going beyond the teaching of language alone.

Keywords: picturebooks; primary; representation; disability; inclusion and immersive literature; social model

Gail Ellis is a teacher, teacher educator and author based in Paris. Her publications include Tell it Again! (with Jean Brewster, British Council, 3rd ed. 2014), Teaching Children How to Learn (with Nayr Ibrahim, Delta Publishing, 2015) and Teaching English to Pre-Primary [end of page 61] Children (with Sandie Mourão, Delta Publishing, 2019). Gail’s interests include children’s rights, picturebooks in ELT, young learner ELT management and inclusive practices.

Introduction

At a time when the educational landscape is rapidly changing and diversity is more and more present in today’s classrooms and in the immediate environment, schools need to provide for the full diversity of learners. They are called upon to cater for learners of increasingly diverse abilities and of a broad range of family, ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Respect and equal commitment to all learners is more important than ever and inclusive school cultures and education are becoming more widespread (Mariga, McConkey & Myezwa, 2014; McConkey, 2001). This includes the right for people with disabilities to receive the education and social support they need to fully participate in society. The social model of disability (Oliver, 1990) was developed in order to reframe how society views disability and to advocate a positive approach to disability. This model shows how individuals are disabled by barriers erected in society, not by their impairment or difference, and focuses on the changes required in society in order to adapt to the needs of persons with disabilities. Using picturebooks that reflect aspects of diversity, including disability, in the Primary English Language Teaching (PELT) classroom can enable the teacher to embrace their wider professional remit by going beyond the teaching of language alone.

In this paper, I discuss the differences between inclusion and immersive literature and offer practical ideas to show how an inclusion picturebook can be reworked and used in an immersive way through appropriate pedagogy. I also show how the social model of disability can be presented to children in an age-appropriate way via the repositioning of a well-known picturebook that can be used to foster social awareness of disability.

Picturebooks and Diversity

Educators need to ensure teaching materials and resources avoid unconscious biases through stereotyping, are appropriate and sensitive to context, and are representative of the learners in their classrooms. In the PELT classroom, picturebooks can offer a flexible and motivating resource (Ellis & Brewster, 2014; Ellis, 2019). Carefully selected, they can reflect many areas of diversity and of human differences, including ability and disability. They can be [end of page 62] used as ‘mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors’ (Sims Bishop, 1990; Botelho & Rudman, 2009). They can mirror children’s reality where they see themselves represented; they can provide windows through which children can see other people’s lives in different places with different experiences; and doors which can take them into and out of different situations. They enable children to recognize who they are and play an important part in developing children’s identities by enhancing their sense of self. All children have the right to see themselves in books and have the ‘right to occupy this literary space’ (Flood, 2018). Malorie Blackman (2013), Children’s Laureate 2013 – 2015, also states on the Inclusive Minds website – a collaboration of consultants and campaigners for inclusion, diversity, equality and accessibility in children’s literature:

All our children have the right to see themselves reflected in the stories available to them. Diversity is more than just seeing yourself reflected in the world of literature, it’s about others being able to see you too. Every child should have a voice. No child should be invisible.

A lack of diversity will impact on how children see themselves and the world around them, on their motivation to read, and on their aspirations to become possible writers and illustrators of the future. As Vail (2013) writes in the Huff Post: ‘Reading is supposed to expand one’s horizons. It’s supposed to enable people to experience lives and cultures and people they would otherwise never get to – and maybe even discover that the people who live those lives aren’t so very different’. Furthermore, Sims Bishop (1997) argues that inclusive literature enables children to learn to appreciate, respect, and affirm diversity, thereby creating a world where democratic pluralism is viewed positively.

Representation of Disability in Picturebooks

Children with disabilities remain largely underrepresented in picturebooks, which means many children find they do not have characters they can relate to or see the world they live in. This situation is also reflected in other media. For example, during his acceptance speech for the 2019 Logie Award for the most popular new talent, Alcott (2019) explained that one of the reasons he used to hate having a disability was because ‘when I turned on the TV, I never saw anybody like me’. [end of page 63]

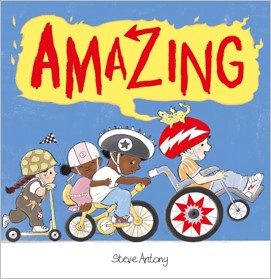

But why is there such underrepresentation? It may be that for some authors it does not occur to them to include disabled characters. Blake (2017) writes: ‘I’m the author of about 60 children’s books. I have to admit it had never occurred to me to create disabled characters but, since Jordi, our son, was diagnosed with cerebral palsy (CP) about seven years ago, I’ve written Oshie (2011) and Thimble Monkey Superstar (2016), featuring main characters with CP’. There may also be reluctance from publishers. Antony (2018), author of the recently published picturebook Amazing, explains: ‘I showed the book to a publisher at the Bologna Book Fair before it was published. She liked it but said it’s too niche and that a picturebook with a wheelchair on the front cover could be a very hard sell’.When characters with disabilities are included in picturebooks, we need to analyse how they are represented. Do they offer authentic and meaningful representations of characters with disabilities so children with and without disabilities can begin to see meaningful similarities between themselves and others? Do they offer respectful representations of disability which allow children ‘to deeply and personally connect with books?’ (Pennell, Wollak & Koppenhaver, 2018, p. 7).

Inclusion and Immersive Literature

Davison (2016), a blogger and an ambassador for Inclusive Minds, identifies two key types of literature. The first she refers to as inclusion literature. This aims to educate, raise awareness of and explain the nature of a disability, generally to non-disabled children. The inclusion of a disabled character is to teach some moral message about disability. As Davison writes:

[f]rom discussing this literature with my disabled peers (Davison is visually impaired), we would prefer to read books where our disabilities were only secondary to the plot. In other words, we do not need to read about our disability and be educated about it, as we live with it every day.

The second type of literature she refers to is immersive literature. In this type of literature, a character with a disability is included, but the disability is not the focal point of the story. The story is centred around another topic, such as an everyday event or an adventure. This type of literature is preferred by the non-disabled and disabled communities alike because [end of page 64] the story is the main focus, not the disability, although there are fewer picturebooks of this type. Table 1 highlights the features of these two types of literature and can be used as a set of criteria when analysing the suitability of a picturebook for different groups of learners.

Table 1: Inclusion and Immersive literature (adapted from Davison 2016) [end of page 65]

Research conducted by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE), Reflecting Realities (2018), was the first UK study which looked at diversity in terms of ethnic representation in children’s publishing. This involved analysing submissions of all children’s literature published in the UK in 2017 that featured black or minority ethnic (BAME) characters to determine to what extent they were represented. A similar study to determine to what extent characters with disabilities are represented in children’s literature would make a valuable contribution to the body of research on disability. It would also enable teachers, authors, illustrators, parents and librarians to more critically evaluate the picturebooks they are sharing with children and to rethink their choice and selection of books.

Representation of Disability in Susan Laughs and Amazing

I have applied the criteria from Table 1 to two picturebooks, Susan Laughs (Willis & Ross, 1999), an example of inclusion literature, and Amazing (Antony, 2019a) an example of immersive literature. Susan Laughs is a rhyming story about a girl called Susan; we see her taking part in everyday activities and experiencing familiar emotions and playing typical games. The use of the ‘withheld image’ means that it is not until the last page that we discover that Susan uses a wheelchair.

When I introduced this picturebook to a class of nine-year-old non-disabled English learners in France, they reflected in silence for several minutes at the end of the story as they assimilated this final image and related it to what they had just heard and seen. They then began asking questions about Susan and returning to the illustrations to check their interpretations. The book emphasizes that someone with a disability can participate in everyday activities, although on closer analysis of the visual and verbal text, we notice that Susan is never unassisted. Her story is told by an unnamed narrator so Susan is voiceless and therefore denied agency. Furthermore, her wheelchair and the lived reality and experience of her disability are erased from the visual narrative, which ‘reinforces ableist norms about human worth’ (Aho & Alter, 2018, p. 307).

Susan Laughs was winner of the 2000 NASEN & TES Special Educational Needs Children’s Book Award. Twenty years ago, it challenged possible preconceptions about people with physical disabilities and presented an innovative and refreshing portrayal of disability. However, is this an accurate and authentic portrayal? Does it mirror the lived [end of page 66] reality of people with physical disabilities? Today, inclusion is more widespread – legislation has improved accessibility in many parts of the world removing barriers and allowing greater mobility and visibility of people with disabilities. Although people who use wheelchairs do not make use of them constantly, would the representation of Susan be more accurate if her wheelchair were visible in more than one illustration? As a Goodreads reviewer observes (Meltha, 2014):

It is not revealed until the final drawing that Susan uses a wheelchair. In a way, this seemed a little deceptive. […] but in many cases under normal circumstances her wheelchair probably should have been visible in several of these situations, so it feels more like they were actually hiding it.

The final sentence reads: ‘That is Susan, through and through – just like me, just like you’. If interpreted literally, it tells us that both the narrator and the implied readers/listeners are also wheelchair users. However, this is not the intended meaning, as Willis (n.d.) explains on her website: ‘Children will enjoy seeing their common feelings and experiences. They’ll be surprised by that wheelchair at the end; and they’ll accept their connection with the child who they’ve come to know is “just like me”.’ It is clear that Susan Laughs aims to teach non-disabled children about disability, so they will become more accepting of someone who has a physical disability and is seen as different from themselves.

Amazing is an example of immersive literature and is a story about the friendship between a boy and his pet dragon Zibbo. The front cover (see Figure 1) shows a diverse group of friends all on wheels – a scooter, a bicycle and a wheelchair. The boy using the wheelchair, the main character, is at the front leading the group of friends. This front cover image is expanded on the fifth double-page spread (see https://www.booktrust.org.uk/news-and-features/features/2019/february/steve-antony-why-ive-made-the-picture-book-they-said-wouldnt-sell/) where the main character is joined by another girl on a bicycle and a boy on a skateboard. The girls are wearing camouflage designs, or violet and yellow flowers and the boys have donned pink or Viking helmets. Another child is wearing a hearing aid. The boy’s wheelchair has stylish wheel covers to celebrate his individuality and to personalize his source of independence. This transforms a functional, medical device into an object of self-expression and challenges negative associations with wheelchairs. [end of page 67]

Figure 1: Amazing, front cover

Amazing is narrated by the main character in the first person, who tells the story about all the things he and Zibbo do together and how Zibbo is a little different. The wheelchair is visible in the illustrations on almost every page, including the front cover and the title page. This provides a visual parallel to the verbal text in which no reference is made to the boy’s disability, and is referred to by Antony (2019b) as ‘incidental inclusiveness’. Antony (2018), who used to work as a student support worker in an Art College with students with special needs. explains:

I did not want the child’s disability to define his AMAZING story in the same way that my students did not want to be defined by their disability. In my mind my students were defined by their hobbies, interests and aspirations. Yes, they required different levels of assistance, but they really didn’t want to be treated any differently to anyone else. I wanted the inclusion of my main character’s wheelchair to be entirely incidental. This is very important. And believe it not, it’s rare to find this sort of incidental inclusion so boldly depicted on the front cover of a UK trade picturebook, even in 2018. [end of page 68]

Amazing presents the reader with one story in text and another in illustration so the pictures and words interact with each other, either wholly or partially filling each other’s gaps or creating their own (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006). The main character’s visual marker of difference, the wheelchair, is visible throughout the story, and the boy is represented as an equal member and participant in the group of friend’s activities. Two images stand out for me in particular. First, the image of Zibbo and the boy, ‘We sail’ where his wheelchair is transformed into a boat, and second, the image where he and his friends are playing hide-and-seek. The wheelchair is visible in both images and the impracticality of hiding behind a tree in a wheelchair is not concealed.

However, the wheelchair has become synonymous with public discourses about disability and tends to be overused to represent any disability experience. Disability is broad in scope and scale and not always obvious. It includes people with sensory, cognitive (including learning disabilities), physical and mental impairments. Authors, illustrators and publishers need to think more broadly than focusing only on wheelchair users and become change agents by creating picturebooks that represent other disabilities, including non-visible disabilities. The Five of Us (Blake, 2014), for example, includes characters with cognitive, sensory and physical impairments and each has their own abilities and strengths which they combine together to overcome a problem

Language Implications and Mediation

There is a focus on content and values when using inclusion or immersive literature. However, there are also language implications for the PELT classroom, especially in relation to agency and voice, such as the shift from third person to first person narrative. This will give children practice in using the range of personal pronouns as well as learning the appropriate terms and discourse associated with different types of disability. Both types of literature, inclusion and immersive, can be used to develop empathy and engagement with a disabled character. An inclusion type story can be used in immersive ways when mediated by the educator seen through a critical disability studies lens, by using appropriate pedagogy to offer new perspectives on the range of ability and disability and on the range of similarities and differences. For example, the teacher can mediate Susan Laughs by engaging children in discussion about disability to help them see meaningful similarities between themselves [end of page 69] and Susan, and not to feel pity or to feel sorry for her. Children can be involved in conversations and discussion around the following suggested questions:

- How are you like Susan? How are you different from Susan?

- Which illustrations would you redraw to reflect the lived reality of Susan’s daily life?

- How would you retell the story from Susan’s perspective? (decentring)

- Can you imagine a different ending to the story?

- What are some of the barriers faced by people who use wheelchairs?

For Amazing, children can be invited to think about wheelchair access in their own school, town, transport systems, etc and design a wheel cover for a wheelchair. They may also like to carry out a project about wheels and how they provide a source of mobility which aids independence.

Social Model Thinking

Children will have different experiences of disability. Some may have disabilities or impairments themselves and many may have family members or friends who have a disability. Others may have had no contact at all with disabled people. Children may have encountered disabled characters in books or films who may have been portrayed as evil, in need of pity or sensationalized as extraordinary. Attitudes and responses to disability will also vary within and across different countries and cultures. There are huge differences among individuals, families, local areas and in state-level systems like education, transport and healthcare. However, Article 23 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, 2019) stipulates: ‘A child with a disability has the right to live a full and decent life with dignity and independence, and to play an active part in the community. Governments must do all they can to provide support to disabled children and their families’. Implementing this right, therefore, forms part of the teacher’s remit even though advocacy for the disabled child in some contexts may be more controversial.

Both types of literature in Table 1 can be used to introduce children to the concept of the social model of disability (Oliver, 1990). It is helpful to situate this model in relation to other models in order to understand why it was created. These include the medical, charity and traditional models. The medical model views disability as an individual ‘problem’: its [end of page 70] focus is on impairments, medical interventions and possible cures. People with disabilities are seen as passive, dependent on the expertise of medical specialists to ‘fix’ them, and, as a result, excluded from a holistic consideration of their needs as unique individuals. The charity model views disability as unfortunate and disabled people as needing pity and charitable giving, including financial contributions. Benevolence and helplessness are seen as major aspects of the charity model undermining the rights and resourcefulness of people with disabilities to make their own decisions. The traditional model stems from certain cultural and/or religious teaching and holds that disability is caused by what has gone before, typically the actions of parents, the wider community or the person themselves. Disability is often seen as a punishment and therefore something that is justified. There is no acceptance, empowerment or a desire to promote the rights of those who are disabled.

The social model was developed by persons with disabilities as a reaction to and as a positive alternative to the models above, to reveal how people are disabled and impaired by barriers constructed in society, not by their impairment or difference.

The barriers include:

- physical (for example, an inaccessible building such as a school, a shop, cinema or a train station platform);

- structural (for example, a segregated education system preventing people with certain impairments from pursuing education in a wide range of areas);

- cultural (for example, a belief that disability is a punishment and therefore brings shame, or is to be exorcised, or is an embarrassment leading to blame, cruelty and/or isolation);

- economic (for example, not acknowledging the financial implications for people requiring paid support to participate);

- attitudinal (for example, believing those with disabilities cannot do certain things and are not able to participate fully in everyday activities).

Such barriers and disabling societal structures prevent disabled people from full participation as equally valued and unique individuals in mainstream activities. Removing these barriers creates equality and offers disabled people more independence, choice and control. [end of page 71]

Introducing Children to the Social Model

Introducing the social model of disability in the PELT classroom enables the teacher to embrace their wider professional remit and contribute to the holistic development of the children in their classes. It can promote understanding of disability with both non-disabled and disabled children and introduces the terms and discourse related to disability.

Winnie the Witch (Thomas & Paul, 1987) has traditionally been used in EFL classrooms to introduce or revise colours and language related to the house, rooms and furniture. By interpreting the story from the vantage of a critical disability lens, Scope – a disability equality charity in England and Wales – shows how Winnie the Witch can be used to introduce children to the social model. The story provides clear similarities and parallels to the social model in a child-friendly and age-appropriate way. Through this lens, Winnie finds Wilbur her cat a problem because she cannot see his black fur in her black house with her black furniture and black paint work. She decides to change Wilbur, which makes him sad, rather than to adapt her house to accommodate him. Finally, Winnie comes to the realization that if she makes adjustments to her house rather than changes to Wilbur, she will remove the problems for them both and they will be able to live together harmoniously.

Table 2 offers practical ideas and a teaching sequence for the PELT classroom that can be used once children are familiar with the story. In this interpretation of the story:

- Winnie represents society;

- Winnie’s house represents the environment;

- Wilbur the cat represents people with disabilities or differences;

- The birds represent the attitudes of others in society.

The class can be divided into four groups. Each group needs a set of the jumbled-up story summary cards and social model thinking cards, copied onto cards of equal size (see Table 2). The picturebook can be read aloud as suggested and children listen, select and sequence the corresponding story summary cards and match them to the social model thinking cards. The teacher pauses after each stage, checks children’s understanding and discusses.

When finished, the children can be asked to describe some of the barriers that people with disabilities may encounter in their own school, town or country and what adjustments could be made to overcome these. [end of page 72]

[end of page 73]

Table 2: Social model thinking in the PELT classroom

(Teaching sequence for Winnie the Witch adapted from Scope

(https://www.scope.org.uk/advice-and-support/social-model-disability-for-kids/)

Celebrating Diversity

Perfectly Norman, which can also be used to encourage social model thinking, is the story about a boy, Norman, who had always been perfectly ‘normal’ until the day he grew a pair of wings. At first, although surprised, Norman is happy and tries out his wings and experiences immense joy. But he then begins to worry about what other people will think of this visual marker of difference and decides to cover up his wings with a big coat. This makes every-day routines difficult and uncomfortable and prevents him from taking part in activities with his friends.

As the story unfolds, we follow Norman through a cycle of emotions until he comes to a moment of understanding and self-realization, ‘It occurred to Norman that it was the coat that was making him miserable, not the wings’. It was Norman’s own attitudes towards his difference, his fear of other people’s attitudes towards his difference and the big coat which had become barriers preventing him from full and equal participation. Norman finally accepts his difference and takes off his coat, revealing his wings and flies into the air, where he is joined by other children who have wings. He is happy again! In an interview with the Book Trust, Percival (2017) explains:

So Norman’s story is not just about accepting our differences; it’s about celebrating and enjoying them too! Using the magical wings as a metaphor for Norman’s difference seemed perfect because they could represent anything – and I wanted the book to be as relatable as possible to all children.

Perfectly Norman is a celebration of difference, inclusivity and individuality. It can be used as a springboard for discussion about differences and similarities and about the barriers in society that people with differences face. Children can be asked what the wings may represent for each child and whether they identify with any of these children.

Kind is a book about kindness and is illustrated by 38 well-known illustrators who have donated their work to help raise money for the Three Peas charity. The illustrations feature monkeys, elephants, lions, cats, dogs, worms and people, and show the many simple [end of page 74] ways in which the world can be made a better place. It shows different types of kindness, ranging from helping, using good manners, to supporting others with language and integration and appreciating differences. Kind can be used to develop visual and emotional literacy as well as civic literacy. Children read the images and the emotions they convey, and also discover examples of an inclusive society. The fourteenth double-page spread illustrated by Steve Antony shows a child in a wheelchair using a ramp to access a tree house, and the second double-page spread illustrated by David Roberts shows an ethnically diverse group of children, two of whom are wearing glasses and one who is wearing a hearing aid.

Conclusion

Whilst the number of picturebooks that include characters with disabilities have increased, this is still an under-represented group. Furthermore, the majority of picturebooks that do feature disabled characters do so in order to convey some moral or educational message about disability. Bringing qualitative and authentic representation of disability in picturebooks into our PELT classrooms is the responsibility of everyone, as carefully selected picturebooks can play a crucial role in the way children can learn to embrace the wide-ranging nature of the term ‘diversity’. They can provide a key way that attitudes towards disability can be positively changed when educators mediate a picturebook by asking explorative questions which guide children to critically question the storyline and the characters’ agency and voice. It is hoped that Table 1 can be used in both pre and in-service professional development to help teachers identify the different types of picturebooks currently available, and to critically explore, select and use picturebooks which reflect the lived reality of disability. Such picturebooks develop social awareness of disability by encouraging social model thinking and meaningful discussion about inclusion in order to establish an inclusive culture in the PELT classroom. It is also hoped that Table 1 can be adapted and applied to other areas of difference such as age, gender, race or ethnicity and sexuality.

Bibliography

Antony, S. (2019a). Amazing. London: Hachette Children’s Books.

Blake, Q. (2014). The Five of Us. London: Tate Publishing.

Green, A. (2019). Kind. Foreword by Axel Scheffler. London: Alison Green Books. [end of page 75]

Percival, T. (2017). Perfectly Norman. London: Bloomsbury. Thomas, V. (1987). Winnie The Witch.

K. Paul (Illus.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Willis, J. (1999). Susan Laughs. T. Ross (Illus.). London: Red Fox.

References

Aho, T. & Alter, G. (2018). ‘Just like me, just like you’. Narrative erasure as disability normalization in children’s picture books. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 12 (3), 303-319.

Alcott, D. (2019) Logie acceptance speech. SBS News. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/sbsnews/videos/467663150685127/

Antony, S. (2018). A boy, his dragon (and a wheelchair). My new book AMAZING and why I wrote it. Blog, SteveAntony, 25 March. Retrieved from http://www.steveantony.com/blog/2018/3/25/a-boy-his-dragon-and-a-wheelchair-my-new-book-amazing-and-why-i-wrote-it

Antony, S. (2019b). The ‘AMAZING’ Blog Tour: Incidental Inclusiveness, School Libraries, Finding Ideas & More. Blog, SteveAntony, 21 March. Retrieved from http://www.steveantony.com/blog/2019/3/21/the-amazing-blog-tour

Blackman, M. (2013). Testimonial, Inclusive Minds. Retrieved from https://www.inclusiveminds.com/testimonials

Blake, J. (2017). Guest post, ‘Where are the disabled characters in children’s fiction?’ Scope, July 2017. Retrieved from https://community.scope.org.uk/discussion/30762/guest-post-where-are-the-disabled-characters-in-children-s-fiction

Botelho, M. J. & Rudman, M. K. (2009). Critical Multicultural Analysis of Children’s Literature: Mirrors, Windows and Doors. New York: Routledge.

Centre for Literacy in Primary Education. (2018). Reflecting Realities. Ethnic Diversity in UK Children’s Books. Retrieved from https://clpe.org.uk/library-and-resources/research/reflecting-realities-survey-ethnic-representation-within-uk-children

Davison, E. K. (2016). Disability in picture books. Fashion eyesta, 26 September. Retrieved from https://fashioneyesta.com/2016/09/26/disability-in-picture-books/ [end of page 76]

Ellis, G. & Brewster, J. (2014). Tell it Again! The Storytelling Handbook for Primary English Language Teachers ( 3rd ed.). British Council. Retrieved from https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/pub_D467_Storytelling_handbook_FINAL_web.pdf

Ellis, G. (2019). Using picturebooks. Teaching Times, 77, 10-11. Retrieved from https://www.tesol-france.org/en/pages/120/the-teaching-times.html

Flood, A. (2018). Ethnic diversity in UK children’s books to be examined. The Guardian, 7 February. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/07/ethnic-diversity-uk-childrens-books-arts-council-england-representation

Mariga, L.; McConkey, R. & Myezwa, H. (2014). Inclusive Education in Low-Income Countries. A Resource Book for Teacher Educators, Parent Trainers and Community Development. Cape Town: Atlas Alliance and Disability Innovations Africa.

McConkey, R. (2001). Understanding and Responding to Children’s Needs in Inclusive Classrooms: A Guide for Teachers. UNESCO. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000124394

Meltha (2014). Goodreads, customer review, posted 21 January, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/996925.Susan_Laughs

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C. (2006). How Picturebooks Work. Abingdon: Routledge.

Oliver, M. (1990). The Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pennell, A. E.; Wollak, B. & Koppenhaver, D. A. (2018). Respectful representations of disability in picture books. The Reading Teacher 71 (3), 1-9.

Percival, T. (2017). ‘It’s not just good to be yourself – it’s perfect!’ Tom Percival on celebrating uniqueness. BookTrust, 16 November. Retrieved from https://www.booktrust.org.uk/news-and-features/features/2017/november/its-not-just-good-to-be-yourself—its-perfect-tom-percival-on-celebrating-uniqueness/

Scope (n.d.). Social model of disability for kids. Retrieved from https://www.scope.org.uk/advice-and-support/social-model-disability-for-kids

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 1(3), ix-xi.

Sims Bishop, R. (1997). Selecting literature for a multicultural curriculum. In V. J. Harris (Ed.), Using Multiethnic Literature in the K-8 Classroom. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon, pp. 1-20. [end of page 77]

UNICEF (2019). A Summary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved from https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/UNCRC_summary-1_1.pdf

Vail, E. (2013). The legacy of Katniss, or, why we should stop ‘protecting’ manhood and teach boys to embrace the heroine. Huff Post, 2 February.

Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/young-adult-novels_b_2199812

Willis, J. (n.d.) Jeanne Willis, My books. Retrieved from http://jeannewillis.com/Book%20Pages/SusanLaughs.html [end of page 78]