| Interdisciplinary Project at Tertiary Level: Recorded Story Read Alouds by Future English Language Teachers

Vanesa Polastri, Analía Urrutia Bustillo and Soledad Martínez |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This is a collaborative article which describes an interdisciplinary project carried out at a state-run English language teacher training college located in the suburbs of Buenos Aires. The project was carried out in a remote teaching context during the first term of 2021. The courses involved are entitled Children’s Literature and Oral Discursive Practices II; these belong to the second year in a four-year course of studies. The final product was the recording of student teachers’ read alouds of children’s literary texts, either in groups or individually, with the aid of the kamishibai paper-theatre technique, hand or finger puppets, shadow puppets or digital tools. The educational aims behind the joint project were to provide an opportunity for the development of confidence to speak in front of a camera or group; to promote the use of the target language orally for a social purpose such as engaging, narrating, describing, clarifying, surprising, and so forth; to encourage the identification, choice and employment of suitable visual aids for their read alouds and, ultimately, to model how to work in a cross-curricular way as a feasible and enriching experience.

Keywords: Children’s literature, oral discursive practices, read alouds, visual aids, student teachers, cross-curricular project

Vanesa Polastri is a teacher of English and a teacher trainer with over 14 years of experience. She is currently in charge of Children’s Literature and Written Discursive Practices II at an English language teacher training college in Buenos Aires.

Analía Urrutia Bustillo is a teacher of English and a teacher trainer with over 18 years of experience. She is currently in charge of the course Oral Discursive Practices at an English language teacher training college in Buenos Aires. She has earned a Diploma in the pedagogy of English language phonetics.

Soledad Martínez is a teacher of English and Art with over 20 years of experience working at kindergarten, primary school and in companies. She is also a professional illustrator. Martínez has worked as an actress and as a materials developer. She has delivered workshops for children, for student teachers and graduate teachers.

Introduction

This cross-curricular project was carried out at the English Language Teacher Training College 41, located in the province of Buenos Aires, during the first term of 2021. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, classes at tertiary level in Argentina were delivered in distance-learning mode throughout 2020 and 2021. A free-of-charge Learning Management System, the Instituto Nacional de Formación Docente (INFoD) platform, provided by the National Ministry of Education, was employed and Zoom encounters were also arranged. The initial idea of this project sprang from the desire to contribute to our student teachers’ learning in a comprehensive way.

First, we meant to help student teachers to interrelate contents from our two subjects, Literatura en Lengua Inglesa y Niñez (Children’s Literature), led by Vanesa Polastri, and Prácticas Discursivas de la Comunicación Oral II (Oral Discursive Practices II), led by Analía Urrutia Bustillo. We wanted the student teachers to see the potential and usefulness of applying what they know about oral language and about children’s literature within a unified product. Second, we intended to generate the conditions for developing their level of confidence in front of an audience or a camera by asking them to record their reading of literary texts aloud. As both subjects belong to the second year in a four-year course of studies, student teachers are in the process of building and strengthening their language proficiency and gaining trust in their abilities to speak in front of others, to make a presentation or to lead a segment of a lesson. Third, we wanted to demonstrate coherence between our words and actions as teacher educators since it often happens that student teachers are asked to work cooperatively and collaboratively, but they do not see this reflected in their educators’ pedagogic choices. In order to merge these three objectives into the elaboration of a product, the final task of the project was the recording, individually or in groups, of the read aloud of a children’s story selected by the student teachers, making use of visual aids.

We decided on read alouds instead of storytelling, the former being dependent on a physical book, while the latter is dependent only on body movement, voice projection and facial expression, without handling or showing the written words or illustrations. The reason for this choice was that it is much more usual for primary school teachers to read in class and, in addition, storytelling skills might take longer to be successfully acquired. However, to read aloud and engage the audience, many storytelling strategies must also be applied. If we were to go on with this joint work in the third year, with Prácticas Discursivas de la Comunicación Oral III (Oral Discursive Practices III) and Literatura en Lengua Inglesa y Juventud (Literature in English for Tweens, Teens and Adolescents), we would definitely take up the challenge of designing a storytelling project in which our student teachers would become teacher-storytellers, building upon the experience depicted in this article and on their consolidation of both linguistic and discursive skills as well as their progressive confidence development.

First of all, we must clarify that the ministerial curricular guidelines followed in our planning changed shortly before the implementation of our project. The newly introduced curriculum design challenged traditional conceptions of language teaching, moving away from decontextualized language dissection into minimal parts, and going along with current paradigms of language as a contextualized social practice, or better still, as multiple social practices. The new course Oral Discursive Practices II aims at the promotion of strategies for social interaction, the comprehension and production of oral texts, as well as the critical analysis of oral practices in general and in teaching situations in particular. The additional course entitled Children’s Literature aims at the development of a wide conception of literature within art, and the exploitation of diverse multimodal literary texts, to allow for aesthetic, socio-emotional, intercultural, cross-curricular and linguistic learning and the encouragement of imagination, creativity, play and critical thinking skills.

Children’s Literature is an annual workshop. Within the yearly plan, student teachers learn about the theoretical underpinnings that will guide their decision-making processes regarding the use of literature in the primary ELT class – in the search for a balance between theory and practice – and focus on the criteria for selecting literary texts. This involves considering students’ interests, the correspondence of conceptual and linguistic aspects with the children’s age and developmental stage, format and genre characteristics and literary devices (rhyme, cumulative expressions), as well as whether the text has an educational message and/or potential for cross-curricular work. For the project they watched some picturebook read-aloud videos, recorded by their teacher and others available on the internet, such as those of Griselda Beacon’s at The BEACON Experience (2020) YouTube channel. In this way student teachers had a reference for their selection of stories and guidance on how to actually carry out their read alouds.

Oral Discursive Practices II is also an annual subject. During the first term of the year, we worked on the oral tools necessary when reading a story aloud. First, we contrasted and compared the sounds in the student teachers’ mother tongue, Spanish, against the sounds of the target language English, in order to find similarities and differences between the speech sounds in the former and the latter. All this we did with the aim of not only making the student teachers aware of such characteristics, but also helping them to monitor their own oral performance. Second, we delved into the world of rhymes and chants in order to focus the student teachers’ attention on the stress patterns of English, which differ greatly from the syllable-timed pattern of their L1. The student teachers listened to authentic material in order to discover the stress patterns of English old-time rhymes and chants, then proceeded to listen and imitate, while some student teachers even dared to make an audio recording of themselves reading some lines. Afterwards, we listened to texts and recognized their stress patterns as well as their pauses.

Student teachers imitated those oral texts and their peers and teacher educator gave them feedback on their production, taking what had been discussed about stresses and pauses as a reference to make informed remarks. While the contents mentioned above were dealt with in that sequential order, they also overlapped when student teachers posed their queries, doubts or when their needs or curiosity emerged. Comparing and contrasting the sounds produced in the mother tongue and the target language, being exposed to rhymes and chants, which are literary texts on their own but are often present in children’s stories, and becoming conscious of stress patterns and pauses in their oral productions enabled the student teachers to concretize the final outcome of the project.

The Interdisciplinary Project

Before the project was formally introduced to our student teachers, we contacted each other via virtual encounters as the classes were held remotely. Through these messages outside our work schedule, we shared ideas, materials and information and turned them into an action plan. After such preparation, in a joint synchronous meeting, the teachers of both subjects introduced the final task the student teachers would undertake. But first, the teacher educators presented different story reading techniques for student teachers to choose from, such as the Japanese kamishibai (紙芝居) or paper theatre, and puppets in their various manifestations: hand and finger puppets made out of socks, gloves, cloth, crochet, soft cardboard, etc. and shadow puppets, playing with light and darkness. Student teachers were asked to select a story, record a story read aloud individually or in teams. They were invited to exploit visual aids either employing a home-made kamishibai or any type of puppets, interpret the story and project their voice. They were encouraged to use props, make gestures, resort to technological tools (such as Zoom backgrounds), and the like. Bland (2015, p. 190) refers to the many elements beyond the words that can make both the reading and the storytelling an event that appeals to the senses,

special clothing such as a story jacket, puppets, sound effects, props or realia can be helpfully involved. However, the art of what I will call creative teacher talk is undoubtedly the area that needs most attention. The teacher-storyteller employs a varied paralanguage involving expressive prosodic features (pitch, tempo, volume, rhythm – including dramatic pauses), exuberant intonation, gasps and, where suitable, even sighs. Some storytellers employ exaggerated gesture and facial expressions, while others have a quieter style. This will also depend on the story and the age of the young learners; the younger the child, the more the storytelling (and classroom discourse generally) should resemble repetitive child-directed speech.

Each teacher educator would assess the video from the perspective of her discipline, adding value to the production insight. Those student teachers who were taking one of the subjects would be given feedback by only one of the teacher educators. It was highlighted that it was not just language per se that was going to be assessed but its use within a communicative purpose, to fulfil a social function. Student teachers were asked, as expressed by Stoetzel and Shedrow (2021a, p. 755), to be aware of ‘the instructional purpose for using these read-alouds or identify a new purpose you might intentionally address’. The goal was not only to teach linguistic items but to contribute to their future students’ intercultural development, to promote empathy, to address a group need or a conflict, to foster imagination and creativity, among others.

Different literacies played a role in the project. Literacy in the mother tongue was built upon since we relied on our student teachers’ knowledge and personal experiences involving reading, narrative structure and reading aloud in their L1, to encourage literacy development in the L2. Visual literacy was also fostered by means of guiding our student teachers on what to show and what not, considering audience understanding of the stories and playing with surprise, also by the choice of colours, techniques and even distance from the camera. Stafford (2011, p. 1) offers a first basic definition of visual literacy: ‘If we consider that the term literacy in its simplest form means the ability to read and write words, then it follows that visual literacy must refer to the ability to read and create images’. Further, visual literacy refers to the processes of meaning-making both when reading images and producing them.

Digital literacy was also attended to, because of the creation of a video which implies making decisions on the devices and programmes to be used in the production and recording of the read aloud. The New Media Consortium (Alexander, Adams Becker & Cummins, 2016) distinguishes three models of digital literacy in their 2016 report: ‘universal literacy’, which means being able to use basic digital tools; ‘creative literacy’, which includes universal literacy and adds more challenging technical skills such as video editing; and ‘literacy across disciplines’, in which digital considerations merge with specific content from other areas. We believe these three models were tackled partly in the asynchronous and synchronous lessons through the navigation of the INFoD platform, by posting in the forum discussion, by downloading material from the resources section, etc. and mainly in the fulfilment of the final task, which required student teachers to produce videos and to do research on other videos on YouTube to see different examples of how teachers read aloud technology-mediated children’s stories. We consider the awareness of the necessity for the development of complementary literacies is a must in ELT.

Support from a picturebook illustrator

Student teachers had around twenty days to comply with the assignment, but from the comments they made in the forum section and in virtual encounters, we realized the relevance of illustrations was not clearly grasped in its full potential. We saw there was a need in our student teachers and tried to cover it by asking Soledad ‘Afra’ Martínez to support us with this issue. Martínez, an Argentinian English language teacher, an actor, a painter and a picturebook illustrator, kindly agreed to deliver a talk for our student teachers. In her virtual session (see Figure 1), Martínez (2021) narrated her journey as an illustrator, describing the steps involved in the process of creating the illustrations for books from the outset. Reading, analysing and highlighting the most important parts of the text, doing research on the main topics of the story, journaling freely, sketching, colouring, and presenting the final illustrations for the actual publishing stage were the main areas detailed by Martínez.

As well as providing concrete examples from books she has illustrated, Martínez told of her experience in connection with negotiating modifications to the artwork with publishing houses and writers, and outlined what elements she prioritized in those cases. She also shared her experience as a teacher of English through art or, in other words, as an art teacher through English (content and language integrated learning) and emphasized the significance of interacting with images actively by means of observation, drama, and art activities. Her personal perspective, which combines two complementary facets – that of the artist and that of the teacher of English – strengthened the awareness of the student teachers regarding the value of illustrations for the creation of meaning beyond verbal text. For images are also text to be read; this proved a key factor to stimulate and develop visual literacy as well as a source of inspiration for those who attended Martínez’ session, both student teachers and teacher educators.

Figure 1. Virtual presentation delivered by Soledad Martínez (2021)

Student teachers’ videos

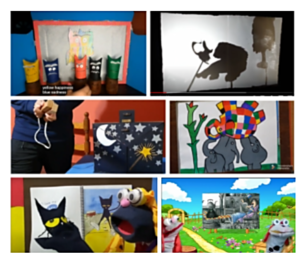

The stories our student teachers chose, the topics they covered and the way in which they tried to make their screen-based renderings accessible to Spanish-speaking children learning English all contributed to the learning process (see Figure 2). It is important to highlight that the videos we are sharing are not meant as the best read-aloud examples by professional storytellers but as the first attempts of teachers in training, and as practical and inspiring ways of scaffolding teacher talk in general, and reading aloud in particular. Student teachers were encouraged to form groups freely. Some worked on their own and others did the assignment in pairs or in larger groups, but comprising no more than three or four members each. It was for most of them the very first time they recorded themselves reading.

The videos were originally planned to be handed in/uploaded within a fortnight, but we were asked to extend the deadline because several of our student teachers were so engaged in the preparation of the kamishibai, the illustrations and/or the puppets that it was taking them longer than was expected to prepare for the video. One student teacher, Agustín, even used wood as a long-lasting material instead of the suggested cardboard, and read a story that tackled the topic of different family configurations, in this case two penguin fathers who adopt a child. His inspiration was the award-winning picturebook And Tango Makes Three (Richardson, Parnell & Cole, 2005). (The student teacher’s video can be accessed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLq8RHsb_5I). Leandro, another student teacher, designed an interactive type of presentation, in which he not only moved the sheets of paper from the front to the back, as in conventional kamishibai practice, but also opened and closed flaps within the illustrations and pulled straps of paper to reveal or cover an object or to introduce a modification in the characters, in the setting or in the storyline. The topic is a Japanese traditional tale highlighting the value of gratitude and raising awareness on interculturality. (The student teacher’s video can be accessed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wiJNRKS3Cgc). This enchanting story is known as The Legend of Kasajizou (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, 2014).

Figure 2. Concrete examples of students’ productions

Sofía could not make up her mind about what visual resources to use. She dressed up as a unicorn and employed some plush puppets to read a fairy tale to her little niece with the objectives of entertaining her and sparking her imagination. She recorded the reading but noticed the result was quite overloaded with visual stimuli and not clear for an audience watching the screen. She decided to resort to kamishibai as well and then her production was much easier to follow. Malena and Candela recorded their voices separately, and afterwards, one of them edited the video by projecting their puppets, which were not the protagonists but the narrators of the story on this occasion, onto a virtual background. They added photos of the selected picturebook to make the story move forward. Melina dared to use shadow puppets, cut out of cardboard, to read a folktale on an unusual friendship between a fierce and large animal and a tiny one. She made use of digital tools, adding a virtual cover to open the video and background music too. In general, the most frequently chosen visual aid was the kamishibai, as it can be reused in future lessons regardless of the story read. Some well-known tales were selected by two or three teams simultaneously, but the immense number of stories read and shared has helped us all to get to know other literary pieces from different cultural backgrounds and to be inspired by the different ways in which we can read aloud, catch the attention of the audience and convey our message with clarity. For that, the language must be handled with an increasing level of proficiency, to which we meant to contribute.

Assessment

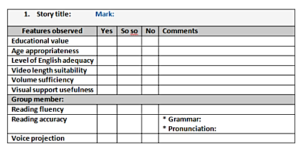

Due to the fact that we have two second-year courses, we watched and gave feedback on 60 videos. That is why we thought of a clear rubric (see Figure 3) to make the assessment process more agile and fair, commenting on set aspects we had previously discussed with our student teachers. The upper part of the chart deals with the story choice and the audio-visual product as a whole; the lower part deals with each student teacher’s performance, so that section was pasted below as many times as was needed, depending on the number of group members.

Figure 3. Rubric designed to assess the audio-visual products and student teachers’ learning

The student teachers who were taking both subjects got feedback from the two teacher educators using the chart in Figure 3. With regard to the student teachers’ feedback on our project, when they sat for the final exam of the children’s literature course, the majority of them reported they were delighted with the activity because they found that the knowledge built around both subjects had a common purpose and was put into practice in an educational situation they will face when they graduate or, even before, in the practicum.

The project also allowed the student teachers to see themselves in action, which fostered self-evaluation, and to see their peers in action too, fostering co-evaluation. They confessed it took them many shots to feel satisfied with the final video, due to either linguistic or technical mistakes and external noises. It was a collaborative work even in cases in which student teachers presented their productions individually, since it reinforced family ties when they had to ask for help, for example in handing over props or holding a frame still while they manipulated the sheets of paper or the puppets. They valued the recorded reading as a resource to use as it is with future groups or as an experiential tool, inviting them to record other read alouds. However, beyond the technological aspect, it was the act of reading itself, the expressivity they gave to it and the love involved in the selection of a story to touch the young audience that they cherished most.

Discussion

We believe the level of student teacher involvement required in the courses Children’s Literature, which is conducted as a workshop, and Oral Discursive Practices, which is interactive by nature, is high. Therefore, we considered it essential to engage student teachers in a final hands-on task. This was a tangible, perceivable product that implied making use of their literacy development, both in their L1 and the target language, their linguistic repertoire in English, especially their oral expression with a real communicative purpose, and the theoretical foundations they were building on in children’s literature pedagogy. Our student teachers also had to handle technological devices and applications to record themselves and edit their videos, enhancing their digital literacy as well. However, as Stoetzel and Shedrow point out (2021b, p. 4), we should not merely use technology per se but ‘push the focus from the “how” of technology integration to the “why”, emphasizing digital literacies as socially situated rather than as isolated technical skills to be mastered’.

Through this joint pedagogical project, we have promoted the construction of a basic framework with concrete suggestions on making informed decisions on the choice of stories for the primary school classroom and to actually experience the readings bodily, keeping the audience in mind and exploiting visual resources of different kinds. We are aware that the recording of a reading, in comparison to reading to primary school students in the physical classroom, provides fewer chances for interaction with the learners. According to Stoetzel and Shedrow (2021b, pp. 5-6), the recorded reading ‘undermines many of the features that characterize effective read-alouds, including providing opportunities for discussion through which children deepen and co-construct meaning’. In spite of this, it was a useful alternative considering the remote teaching scenario we were all in. For future video recordings, the read alouds could be usefully upgraded by making them more intentionally interactive, for example by addressing questions to the audience and pausing at specific moments to leave room for thoughts to occur.

Conclusion

With this report we have tried to show how we have departed from a traditionally discrete approach to language, in which loose sounds are repeated meaninglessly or isolated word lists are learned by heart. We have also departed from a discrete approach to teacher education, in which each course is a separate island and the content tackled is not interrelated in a cross-curricular way. Working together as educators from the same institution, we recognized a need in our courses and communicated with an expert in the field who generously gave her time and experience to support us. We conceive language as discourse, in Hallidayan terms (Halliday, 1979), in context and embedded in a discourse genre, in this case narrative, with the social function to connect, move, entertain, invite reflection, and so forth.

The student teachers used the target language and, as they recorded themselves, they could go back to the videos and reflect – alone and with their peers – upon their performance. As they had the possibility of carrying out the final task in groups, they learned with and from their peers throughout and, since they had to paste the link of their videos in a common Google document that became our repository, all their productions were shared. This allowed the enjoyment of watching the recordings of others but also the discovery of new stories and creative ideas on how to read them, and the use of visuals such as hand-made drawings and puppets.

Finally, we, their teacher educators, wanted to do interdisciplinary work, showing it can and must be done at college too and it is always enriching for all participants. This experience has turned into a valuable instance of learning, as student teachers learned from their educators, the educators learned from their student teachers, student teachers learned from their peers and the educators learned from their colleagues.

Bibliography

Martínez, Soledad (2021, July 10). Sole Afra 2do 1era. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WECc4u3-51A.

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan (2014). The Legend of Kasajizou. Public Relations Office, Government of Japan. https://www.gov-online.go.jp/eng/publicity/book/hlj/html/201412/201412_09_en.html

Richardson, Justin & Parnell, Peter, illus. Cole, Henry (2005). And Tango Makes Three. Simon & Schuster.

Beacon, Griselda (2020). The BEACON Experience [YouTube channel]. Retrieved May 10, 2021 from https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCX_w9ti6bt1fDYEFcITuuWw

References

Alexander, B., Adams Becker, S., & Cummins, M. (2016). Digital literacy: An NMC Horizon Project strategic brief (Volume 3.3). The New Media Consortium. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2016/6/2016stratbriefdigitalliteracy.pdf

Bland, J. (2015). Oral storytelling in the primary English classroom. In J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to young learners: Critical issues in language teaching with 3-12 year olds (pp. 183-198). Bloomsbury.

Halliday, M. (1979). El lenguaje como semiótica social. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Stafford, T. (2011). Teaching visual literacy in the primary classroom: Comic books, film, television and picture narratives. Routledge.

Stoetzel, L., & Shedrow, S. (2021a). Making the move online: Interactive read-alouds for the virtual classroom. The Reading Teacher Journal, 74(6), 747-756.

Stoetzel, L., & Shedrow, S. (2021b). Making the transition to virtual methods in the literacy classroom: Reframing teacher education practices. Leadership in Teaching and Learning, 13(2), 127-142.