| ‘Then is the whale happy’: Student Teachers Trial Picturebooks for Differentiation Opportunities in the Primary English Language Classroom

Regula Fuchs and Kristel Ross |

Download PDF |

Abstract

The article considers the potential but also the challenges that teachers and student teachers experience when using children’s literature in the Swiss primary English language classroom. We discuss in this paper in what ways student teachers can benefit if they are supported during their teaching practice with specific models for picturebook read-aloud sequences. These models focus on one of the main challenges mentioned by in-service teachers when asked about their use of children’s literature, namely the extensive heterogeneity in their classes. It is argued that the use of the models is promising, because by transferring and applying them in primary English language classrooms, the student teachers gain new experiences. In subsequent discussions with peers, mentor teachers and English language methodology experts, the student teachers can further develop their professional expertise. The potential of the models for student teachers is evaluated based on reflection logs written by the student teachers after the experience.

Keywords: picturebook read aloud, primary English language classroom, heterogeneity, models for differentiation, teaching practice

Regula Fuchs (PhD) works as a teacher educator at the Zurich University of Teacher Education (Pädagogische Hochschule Zürich). She used to be a primary teacher and has over 25 years of experience as a teacher. Her research interests include differentiated instruction, classroom-based research and children’s literature in the primary English classroom.

Kristel Ross (PhD) works as a teacher educator at the Zurich University of Teacher Education (Pädagogische Hochschule Zürich). She is a member of the board of the Swiss Association for Foreign Language Teaching and Learning (Association en didactique des langues étrangères en Suisse / ADLES). Her research interests include immersive teaching, foreign language methodology and plurilingualism.

Introduction

Children’s literature plays an important role in English language teaching at primary level (Bland, 2019; Bland & Lütge, 2013; Cameron, 2001; Elley, 1989, 2000; Ellis & Brewster, 2002 & 2014; Ghosn, 2013; Lütge, 2018; Nation, 2013; Tomlinson, 2013). Through stories, children can enter an imaginary world and at the same time encounter authentic language; thus, a holistic approach to language learning becomes possible. Certain stories seem to be more fascinating to children than others. It is these stories which children would like to read or to be told again and again. They have content that is relevant for children and are written in a way that makes it possible for them to empathize with the characters or learn more about why characters act in a certain way in a specific situation. Nikolajeva (2014) distinguishes between ‘immersive’ and ‘empathic’ identification. ‘In the former case, the reader uncritically shares the character’s thoughts and feelings; in the latter, they understand the character’s thoughts without necessarily sharing them’ (p. 91).

The two picturebooks which were chosen for the project described in this article provide many opportunities for ‘empathic’ exploration. The Snail and the Whale by Julia Donaldson and illustrated by Axel Scheffler (2004) and Giraffes Can’t Dance by Giles Andreae and illustrated by Guy Parker-Rees (2014) concern universal human issues, such as helping each other, loneliness, getting to know one’s strengths and gaining confidence: all points being relevant for children.

The Snail and the Whale (see Figure 1) is the story of a tiny snail who travels on the tail of a humpback whale around the world. But one day the whale swims too close to the shore, gets stuck in the sand and cannot swim away anymore. The snail calls for help in the nearby village. Children and firefighters together can finally save the whale, allowing the two to continue their journey. The story is written in rhyme and the beautifully executed pictures support the children’s understanding. The content of the story invites the children to talk about their own experiences in life, for instance, a situation in which they were able to help a friend.

The second picturebook, Giraffes Can’t Dance (see Figure 2), is the story of Gerald, a giraffe who thinks that he cannot dance well. The other animals all laugh at him when he tries. Finally, Gerald finds his own music and suddenly, he dances well. This story, similar to that of The Snail and the Whale, is written in rhyme, beautifully illustrated and the pictures support understanding. Also, the content invites the children to talk about their own experiences in life, for example, how they feel when someone laughs at them and how they react.

Figure 1. (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2004)

Figure 2. (Andreae & Parker-Rees, 2014)

The language in these well-crafted stories has a certain level of complexity. If teachers support the children’s understanding while introducing stories, and help the children to think about characters in an empathic way, feelings of self-confidence and motivation towards English language learning can evolve. This is because children realize that they can understand a story written in English without understanding every single word. Children might, thus, later be motivated to try to read a story or parts of it themselves and, with appropriate support, this can then be a next step towards what Thaler (2012) calls ‘the virtuous circle of the good reader’ (p. 191; see also Kolb, 2013).

In Swiss primary English language classrooms, there are children who find it very hard to learn English, but in the same classroom there are often children who speak English at home; children’s literature has a huge potential to cater for all these different levels. Astonishingly, many Swiss primary English teachers hardly use any children’s literature in their classrooms, or if they do use stories, they often use the ones written for much younger children (with simplified language or content not relevant for the children), as classroom visits over several years and informal surveys and interviews with in-service teachers led by the authors of this article have shown. And although observations and informal surveys cannot be considered representative, they can indicate tendencies and are often worth following up with more research. The fact that many teachers apparently do not make full use of the potential of children’s literature in their English language classrooms gave rise to the project described in this article.

The children’s literature project has the following aims:

a) to explore the reasons why in-service Swiss primary English teachers are reluctant to use children’s literature or if they do, use books for much younger children.

b) to raise pre-service teachers’ awareness of the affordances of children’s literature for primary ELT and to give them the opportunity to experience the major potential of children’s literature in terms of children’s motivation and language learning,

c) to evaluate the potential of specific models on how to tell stories in heterogeneous classrooms.

Teacher Education Children’s Literature Project

Many researchers stress the importance of collaboration in young learners’ language teacher education research (Garton, 2019, p. 275). In our project, student teachers, mentor teachers and English language methodology experts interacted in various ways. The project started in September 2019 and finished in February 2020 right before Covid-19. Twelve student teachers in their third semester at the Zurich University of Teacher Education had the opportunity to tell a picturebook story in a primary English language classroom (see section Procedure for details).

Knowledge as a cognitive tool becomes relevant if it is placed in a specific context (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 33). It is thus important for student teachers to teach in actual classrooms to be able to develop a deeper understanding of teaching approaches. From a cognitive-apprenticeship perspective, learning takes place within a modelling-coaching-scaffolding-fading-reflection framework (Brown, Collins & Duguid,1989; Helmke, 2009, pp. 207-208). In a ‘zone of proximal development’ (Vygotsky, 1978) that is with the help of models, scaffolds and collaborative social interaction with expert teachers, student teachers can develop their professional expertise, in an approach based on socio-constructivism. The cognitive-apprenticeship approach was chosen by the authors of this article because of the differences among the student teachers regarding their teaching competences and their prior knowledge concerning children’s literature and its use in the primary English language classroom. Some student teachers already had some knowledge in terms of how to read aloud picturebooks in an L1 classroom. This knowledge, however, mainly focused on the use of gestures or voice modulation in order to tell a story in a lively way. To support children by including various types of questions when telling a story, so that all children in the English language classroom can understand the story, think about the content and participate on their specific level, was new to all student teachers (for different types of questions, see Table 1).

The modelling-coaching-scaffolding-fading-reflection approach has the advantage that inexperienced student teachers can use step-by-step models on how to tell a story (with concrete questions indicated in the picturebook text) and more experienced student teachers can be supported merely with scaffolds (for example, various types of questions – see Table 1 – that they can include themselves in a picturebook text). The modelling phase of the approach took place in the first session of the university course: an oral example of how to read aloud a picturebook with a focus on differentiated questions was given. Prior to their own teaching, student teachers were also provided with coaching; this consisted in support while planning their picturebook lessons. The written instructions served as scaffolds for their planning: for example, what kinds of questions can be asked in which part of the story to support understanding and at the same time to challenge strong learners. After the picturebook lessons in the classroom, the student teachers received feedback from their mentor teachers and wrote reflection logs. Back in the course the student teachers shared their experiences and thoughts.

The children in the classes taking part in the project had been learning English for two or three years. They were 10- or 11-years-old and in either 4th or 5th grade. During the project, the 12 student teachers also interviewed their mentor teachers about their views on the use of children’s literature in the English language classroom. The mentor teachers’ responses, as well as the reflection logs written by the student teachers after their teaching experience, form the basis for this article (see section Procedure for more details).

Methodological Support for the Student Teachers

Step-by-step instructions

The student teachers were given step-by-step instructions on how to read aloud their picturebook and at the same time cater for the different levels of the children in their primary English language classes. The need for differentiated instruction in ELT to meet learners’ individual needs is mentioned by various researchers (Le Pape Racine & Brühwiler, 2020, p. 280). A study by Cabrera and Bazo Martínez (2001) also showed that children only understood the content of a story when the teacher supported them, not only with linguistic but likewise with interactional adjustments, such as comprehension checks in form of questions when telling the story. Linguistic adjustments on their own (such as simplifying vocabulary and grammar, speaking speed) did not provide enough support for the 60 ten-year- olds with two years of EFL learning who took part in the study.

Pro-actively differentiated questions were prominent in the instructions given to the student teachers because they allow catering for all levels in the classroom. The questions support the children’s understanding and at the same time encourage all children to use the English language actively. The type of question influences the complexity of the language used in the answer (for examples see Table 1). Questions with a choice of answers already included in the question (see type 2 in Table 1) can encourage insecure learners to participate. Open questions (see type 3 in Table 1) can challenge confident and strong learners. To cater for all levels in the primary English language classroom is highly complex for student teachers. Therefore, the aforementioned modelling approach was chosen to both support all student teachers at their various levels of English language teaching competence as well as guide the mentor teachers themselves who did not have much experience with selecting relevant stories for the English language classroom and reading aloud picturebooks with a differentiated approach.

| Types of questions | Examples |

| Yes/No questions (type 1) | Is the person/animal happy? |

| Questions with a choice of answers (type 2) | Is the person/animal happy or sad? |

| Open questions (type 3) | Why is the person/animal happy or sad? What do you think is going to happen next?

What would you do? What can you see in the picture? |

Table 1. Examples of differentiated questions

Procedure

The project consisted of eight steps (see Table 3). In a first step, the theoretical background (what is children’s literature, why is it important for the primary English language classroom?) was covered in the course. The student teachers were given an oral example on how the picturebooks could be read aloud. Furthermore, the student teachers received written step-by-step instructions including differentiated questions for these stories (Table 1) and instructions that showed general activities of storytelling (see Table 2). This was done in order to make a transfer to other stories possible (on step-by-step instructions with differentiated questions and general activities. see Fuchs, 2019).

| Types of activities | Examples |

| Pre-activity | Starting with a photograph or audio (e.g., sound made by whales) to guess what the story could be about

Activating prior knowledge with differentiated questions (see Table 1) |

| While-storytelling activity | Looking at the story from a character’s perspective

Catering for all levels by asking differentiated questions (see Table 1) |

| Post-activity | Having the children retell the story with the help of pictures

Making a drawing and annotating with words or sentences or writing a follow-up story |

Table 2. General activities for picturebook read-aloud sequences

Then the student teachers planned their picturebook read-aloud sequences and wrote their lesson plan (step 1 in Table 3). The picturebook read-aloud sequences were practised in the course and the student teachers gave each other peer feedback in terms of the use of differentiated questions (step 2 in Table 3). Additionally, the student teachers chose 16 nouns that covered the main content of their stories. These nouns would be tested directly after the picturebook sequence and again four weeks later to check the long-term acquisition of the words. For this a ‘discrete point testing’ approach was chosen (Hass, 2006, p. 273). This kind of test focuses on a narrow aspect of language, such as single words and not yet on chunks of language or communicative competence. For each word, there was a choice of four pictures for the children to choose from. The pictures were not part of the story. For the long-term test, new pictures were chosen, and the order of the words was changed (step 3 in Table 3). This rather narrow linguistic approach was chosen in order to alert the student teachers to how much language the children can acquire by merely listening to stories told in a differentiated way.

Mentor teachers had been asked beforehand to make sure that the picturebooks and the words had not already been introduced in the classroom. But of course, some of the children might have encountered the words before. The picturebooks were read aloud in class in a twenty-minute slot (step 4 in Table 3). The tests were done immediately after the picturebook sequence and again four weeks later. And, in order to check not only receptive but also productive knowledge, the teachers chose four children with average competences, that is, neither the weakest nor the strongest learners in the classes; then these children were asked to retell the story with the help of the pictures (step 5 in Table 3). The student teachers recorded the session and later analysed the language in terms of words and chunks from the story that the children had used when trying to retell the story, and also in terms of strategies that the children applied while doing this. The tests had the aim of focusing the student teachers’ attention on the children’s language learning; though, in this small-scale setting, it was of course not possible to get valid results on the children’s language learning. However, the children’s language learning and also their thoughts about the content of the stories and learning English with picturebooks could be followed up in a different project.

| Step 1: Introduction to children’s literature in ELT and differentiated instruction, introduction of picturebooks and step-by-step instructions, planning of storytelling stages

Step 2: Read-aloud practice and peer feedback regarding the use of differentiated questions while telling the story Step 3: Introduction of test theory and writing tests Step 4: Telling the stories in the classrooms; testing words referring to pictures (short-term) Step 5: Testing words referring to pictures (long-term) and retelling of story by 4 children Step 6: Interviews with mentor teachers Step 7: Writing of reflection log Step 8: Discussion, analysis and interpretation of experiences and data in the module |

Table 3. Teacher education project procedure

The student teachers interviewed the mentor teachers (step 6 in Table 3) about their use of children’s literature with the following questions (all questions in Tables 4 and 5 are translated from German):

|

1. How often do you tell stories in your ELT classroom? 2. What kind of potential do you see? 3. What kind of challenges do you see? |

Table 4. Interview questions for mentor teachers

Questions 2 and 3 were very open in order to give the mentor teachers the opportunity to formulate their thoughts. The mentor teachers’ answers were written down by the student teachers and brought to the course to be analysed, categorized and interpreted by all student teachers together.

After their classroom experience, the student teachers wrote reflection logs (step 7 in Table 3) based on the questions in Table 5:

|

a) Describe your impression of the classroom atmosphere and the children’s motivation during the storytelling sequence? b) How did you feel? c) Describe your impression of the children’s language learning. Give examples and also consider the part in which the children tried to retell the story. d) How about your personal gain of language? e) Describe your impression of the potential of stories for less able as well as for strong learners of English based on your experiences in this project.Give examples. f) Did your attitude towards telling stories in the ELT classroom change? If so, in which way(s)? g) Evaluate the usefulness of the step-by-step instructions. |

Table 5. Follow-up questions for student teachers’ reflection log

The student teachers discussed their experiences in the course with their peers and lecturers. The data they had collected were analysed, categorized and interpreted (step 8 in Table 3). Their reflection logs were handed in and analysed, categorized and interpreted by the researchers.

Findings

Interviews with the mentor teachers

For the interviews with the mentor teachers, the student teachers had been given questions by the researchers. The collected answers were analysed and categorized, and new sub-categories were formed inductively by the student teacher group. This procedure was based on Mayring’s (2015) qualitative content analysis.

The question about the mentor teachers’ view regarding the potential of children’s literature (see Table 4) aimed to find out whether the mentor teachers were aware of its potential for differentiation in the language classroom and which other aspects they were aware of. The question about the challenges perceived by mentor teachers sought to explore in what ways the mentor teachers needed more support. The following two sub-categories and main aspects became prominent:

| Awareness of potential | · Children are highly motivated, children are motivated if the stories have a connection to their world, the message of the story is important, empathy with the main character is possible.

· Pictures help to understand the story, listening skills and strategies can be taught, words are taught in context. · A change in the personal teaching approach becomes possible. |

| Support needed | · Difficulty to find good stories, time for preparation is high.

· No time during teaching, content of coursebook has to be covered. · Stories are too difficult for the children, they can’t understand the content, stories are too difficult for some children at that stage of English learning. |

Table 6. Sub-categories of mentor teachers’ voices

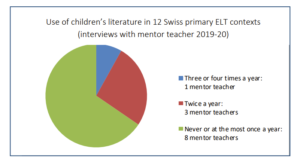

The answers collected in the interviews showed that eight out of twelve mentor teachers had never used children’s literature or, at the most, once a year in their ELT classrooms. Three mentor teachers used children’s literature twice a year and only one mentor teacher uses children’s literature regularly, that is three to four times a year (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mentor teachers’ use of children’s literature

Student teachers’ reflection logs

The student teachers’ reflection logs were written after their experience in the classrooms had taken place and were approximately two A4 pages long. The logs focused on aspects such as motivation, language learning and student teachers’ attitudes towards children’s literature in the English language classroom (see questions in Table 5). The student teachers’ logs were collected, analysed and categorized by the researchers. Again, the procedure was based on Mayring’s (1983, 2015) qualitative content analysis.

With regard to the aim of the project, the data collection and analysis was based on the following three questions: 1. How did the student teachers feel during the story sequence? 2. How did the children (strong and less able learners) react as seen from the student teacher’s perspective? 3. What was the student teachers’ attitude after the experience? The aim of the first question was to find out whether the models were helpful or whether the student teachers would have needed additional support. The second question had the aim to focus the student teachers’ attention on the children’s thinking and learning. The third question focused on the student teachers’ attitude to find out whether they recognized the potential that children’s literature has in the English language classroom and whether they would use children’s literature in their own future classrooms.

The following sub-categories and main aspects were found:

| Helpfulness of models | · Example in course was helpful, storytelling by professor was basis for planning.

· Written instructions with differentiated questions were helpful. · Written instructions provided support, written instructions as inspiration. · Written instructions were helpful as a basis to formulate one’s own questions. · Written instructions seen as helpful because they provide a focus on the most important aspects when telling a story. Instructions seen as very helpful because they showed how to tell a story professionally. |

| Children’s reaction | · High level of motivation, children laughed, were having fun.

· Children were very concentrated / no disturbances. · High level of participation. · Children empathized with main character. · Very good atmosphere. · Strong learners were very active. · Less able learners were very active. · Strong learners used whole chunks from story. · Less able learners used single words from story. · Children used language creatively. |

| Student teachers’ feelings | · Liked story.

· Felt well-prepared and looked forward to sequence. · Great atmosphere, nice to see how motivated the children are. · First nervous – reaction of children – felt relaxed. · Felt enthusiastic. |

| Student teachers’ attitude | · Want to use stories again / nice stories / developed enthusiasm for stories.

· Valued good atmosphere. · Surprised how much language the children remembered. · Developed deeper understanding of methodological approach. · Learned that differentiation is important. |

Table 7. Sub-categories of student teachers’ voices

In the sub-categories (Table 7) the following aspects became prominent:

- relaxed and motivated atmosphere in the classroom,

- step-by-step instructions were seen as helpful for inspiration and planning,

- the positive reaction of the children influenced the way the student teachers felt themselves,

- the student teachers were surprised by how much English language the children learned/used,

- less able and strong learners participated actively during the storytelling sequences.

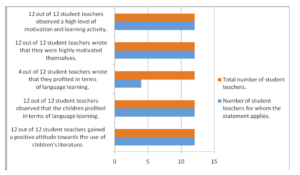

All student teachers had experienced a high level of motivation, both on the children’s part and regarding themselves. Furthermore, they noticed a gain in language on the children’s level (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Student teachers’ reflection logs

Retelling the story – the children’s language production

A few weeks after telling the story, the student teachers showed a group of four children pictures from the book and asked them to retell the story. They recorded what the children said in order to see how much language from the story the children used actively. Table 8 illustrates the connection between the original text and the kind of language the children were able to produce. To provide an opportunity for the children to speak, the student teachers (S) asked a few questions in between. The example shows that quite a number of words from the original text – such as snail, whale, sand, sea, pool and firefighters – were used by the children when they tried to retell the story. This is also what the student teachers referred to in their reflection logs (see under Discussion – student teachers’ perspectives). Not only did the children produce single word utterances, but they used whole chunks of language as well.

| Original text in the picturebook (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2004, unpaginated) | Language that the children produced |

| […]

And this is the whale lying beached in a bay. ‘Quick! Off the sand! Back to sea!’ cried the snail. ‘I can’t move on land! I’m too big!’ moaned the whale. The snail felt helpless and terribly small. Then, ‘I’ve got it!’ she cried, and started to crawl. ‘I must not fail,’ said the tiny snail. |

S: What’s happening in the story?

Child 1: The whale gets washed up on the shore. Child 2: The whale comes fast and the whale comes on the sand. Child 3: The whale is in the sand. Child 4: The snail calls help. |

| This is the bell on the school in the bay,

Ringing the children in from their play. This is the teacher […] This is the board […] And this is the snail […] ‘Look!’ say the children. ‘It’s leaving a trail.’ This is the trail of the tiny snail, A silvery trail saying…Save the whale. |

S: Where is the snail?

Child 1: In a classroom. Child 2: The snail writes something. |

| These are the children, running from school,

Fetching the firemen, digging a pool, Squirting and spraying to keep the whale cool. This is the tide coming into the bay. And these are the villagers shouting, ‘Hooray!’ As the whale and the snail travel safely away… |

Child 1: The firemen do water of the whale. Then is the whale happy. Because the whale like water and so can the whale move and go in the water, in the sea.

Child 2: The children do a hole and so make a pool for the whale and so can he move out in the sea. |

Table 8. Children’s voices; our emphasis

Discussion

Interviews with teachers

Although only 12 mentor teachers were part of the project, their answers showed a tendency similar to the observations and informal surveys conducted by the authors of this article in previous years (see Introduction). During their interview, all 12 mentor teachers mentioned the high motivation of the children when asked about the potential of children’s literature in the primary English language classroom. According to the mentor teachers, the motivation was highest when the story made a connection with the children’s world possible and when the children were able to empathize with the characters in the story.

Further positive aspects mentioned by the mentor teachers were that stories offered variety in their teaching approach because there was a change from their usual way of teaching. The support provided by the pictures when telling a story was found helpful by the mentor teachers. Additionally, the mentor teachers mentioned that various skills and competencies could be trained in story sessions.

However, the mentor teachers did not recognize the potential of stories for differentiation, as they mentioned this point under challenges. Significantly, 11 out of 12 mentor teachers mentioned the extensive heterogeneity in their classrooms and saw it as a reason not to use stories, or not to use them more often. They argued that it was difficult for them to select stories and to prepare them for their classes so that all the children could profit during a story session. Another point brought up was that they could not find children’s literature in their coursebooks. Some mentor teachers said that they thought stories were too difficult for the children at that stage in their English learning. One reason for this statement might be the conviction that children need to be able to understand almost all the language in a story before coming into contact with it. This might also be the reason why many teachers use stories with very simple language and stories that were originally intended for much younger children than the ones in their foreign language classroom. The teachers seem to lack strategies regarding how to tell a story: using questions and other means to support the children’s understanding and thus, to make a positive first experience with literature possible for the children. At the same time, they seem to lack criteria and time to select valuable stories that fascinate the children in their classrooms.

Student teachers’ perspective

Although only 12 student teachers participated in the project, their voices could be seen as an inspiration to conduct further projects on a larger scale. All student teachers mentioned in their reflection logs how motivated the children had been during their picturebook read-aloud sequence (see Figure 4).

Some student teachers recognized the relationship between their careful planning based on the step-by-step instructions and the children’s motivation (all student teachers’ quotes are translated from German):

I was personally very motivated during the storytelling. I thought the story was great, I had prepared myself for the storytelling and I wanted the children to like the story as well. That’s why I put a lot of effort into it and simply enjoyed the sequence… I feel this is an important competence that I would definitely like to use in my future job as a teacher. The overall impression in the module group was consistently positive. The motivation of the children was very high in all groups, they listened with interest… (C.F.)

Whereas only four student teachers wrote that they had profited themselves from telling the story in terms of language learning, they were surprised by how many words and chunks the children remembered receptively and productively and they also mentioned the creativity of the children when trying to retell the story.

It is fascinating that the results were very high for a relatively short input… However, what could not be tested exactly is what else the children learned [from] the story. (N.R. & N.T.)

I was surprised by how much was remembered by the children after 4 weeks and was incorporated into the productive vocabulary. (F.Z.)

The children still knew a lot about the story. Although they did not know all the words of a sentence in English, they discovered ways to say the words so that we could still understand what they wanted to say:

‘The firemen do water of the whale. Then is the whale happy. Because the whale like water and so can the whale move and go in the water, in the sea.’ (A.M. & O.M., our emphasis)

Whereas the teachers saw the heterogeneity in the classes as a difficulty and as a reason not to use stories, the student teachers mentioned not only how stronger, but also less able learners, participated actively during the story session:

We noticed that the stronger pupils were more active in class (asking/answering questions, joining in, etc.). However, you can see in the tests that the children who were rather inactive also achieved good results. For example, pupil H … [she] actually belongs to the weaker pupils… (J.V. & R.Ü.)

One pupil with special needs was very active during the storytelling sequence. (N.F. & C.T.)

All student teachers stated that they had gained a positive attitude toward the use of stories in the primary English classroom and explained that they would use stories in their own future classes.

Neither of us had any experience of storytelling in the foreign language classroom, either as students or as pupils. Even [in] our practice classes stories were never told during the teaching of foreign languages. We developed great joy and enthusiasm for storytelling… (J.V. & R.Ü.)

We will definitely include stories in our future foreign language lessons. (A.M. & O.M.)

Conclusion

The project described in this article took place on a very small scale. However, the multifaceted approach allowed a collaboration between student teachers, mentor teachers and language methodology experts. The data gained from the interviews with the mentor teachers and from the reflection logs written by the student teachers reflect the whole complexity of what teaching children’s literature in the primary English language classroom implies. The project showed how important it is for methodology experts to consider and value teachers’ and student teachers’ voices and may inspire projects that can be undertaken on a larger scale. Support materials can be tested by student teachers, as occurred in the project. They carry, thus, additional support into the field and if the models prove fruitful for the student teachers, and if the children’s reaction is positive, some mentor teachers may feel inspired as well and take up the new ideas/approach for their own teaching.

Children’s literature and instructions on how to use it with a differentiated approach in mixed ability classrooms could, of course, be included in coursebooks. However, publishing rights make this a very difficult undertaking, and consequently, many coursebook writers and publishers refrain from it. The project described in this article made it possible for student teachers to read aloud picturebooks in mixed-ability classrooms by using differentiated questions while starting to tap into the huge potential that children’s literature has for the primary English language classroom. The student teachers explained that they would continue to use children’s literature in their own future English lessons. One of the aims of the project has thus been reached. Consequently, more and more children will be able to benefit from the wonderful world of stories.

Bibliography

Donaldson, Julia, illus. Axel Scheffler (2004). The Snail and the Whale. Macmillan Children’s Books. (Read aloud of story see https://youtu.be/EmMnaSkeKqQ.)

Andreae, Giles, illus. Guy Parker-Rees (2014). Giraffes Can’t Dance. Hachette Children’s Group. (Rendition of story in song see https://youtu.be/Zzb5Acl-n70.)

References

Bland, J., & Lütge C. (Eds.). (2013). Children’s literature in second language education. Bloomsbury.

Bland, J. (2019). Teaching English to young learners: More teacher education and more children’s literature! Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 7(2), 79-103. https://clelejournal.org/article-4-teaching-english-young-learners/

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

Cabrera, M. P., & Bazo Martínez, P. (2001). The effects of repetition, comprehension checks, and gestures, on primary school children in an EFL situation. ELT Journal, 55(3), 281-288.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching languages to young learners. Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2002). Tell it again! The new storytelling handbook for primary teachers. Penguin.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2014). Tell it again! The storytelling handbook for primary English language teachers (3rd ed.). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/pub_D467_Storytelling_handbook_FINAL_web.pdf

Elley, W. B. (1989). Vocabulary acquisition from listening to stories. Reading Research Quarterly, 24(2), 174-187. https://doi.org/10.2307/747863

Elley, W. B. (2000). The potential of book floods for raising literacy levels. International Review of Education, 46(3-4), 233-255. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004086618679

Fuchs, R. (2019). I’m going to tell you a story: Praktische Ideen für einen motivierenden und kompetenzorientierten Englischunterricht auf der Primarstufe. hep-verlag. https://www.overdrive.com/media/4617616/im-going-to-tell-you-a-story-e-book.

Garton, S. (2019). Early language learning teacher education: Present and future. In S. Zein, & S. Garton (Eds.), Early language learning and teacher education: International research and practice. (pp. 265-267). Multilingual Matters.

Ghosn, I.-K. (2013). Storybridge to second language literacy: The theory, research and practice of teaching English with children’s literature. Information Age Publishing Inc.

Hass, F. (Ed.). (2006). Fachdidaktik Englisch: Tradition, Innovation, Praxis. Klett.

Helmke, A. (2009). Unterrichtsqualität und Lehrerprofessionalität: Diagnose, Evaluation und Verbesserung des Unterrichts. Klett/Kallmeyer.

Kolb, A. (2013). Extensive reading of picturebooks in primary EFL. In J. Bland, & C. Lütge (Eds.), Children’s literature in second language education (pp. 33-41). Bloomsbury. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472552815.ch-001

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Le Pape Racine, C., & Brühwiler, C. (2020). Gestaltung des Sprachenunterrichts Deutsch, Englisch und Französisch aus Sicht der Schüler/innen und Lehrpersonen am Stufenübergang von der Primarstufe zur Sekundarstufe I. In G. Manno, M. Egli Cuenat, C. Le Pape Racine, & C. Brühwiler (Eds.), Schulischer Mehrsprachenerwerb am Übergang zwischen Primarstufe und Sekundarstufe (pp. 257-285). Waxmann.

Lütge, C. (2018). Literature and film – Approaching fictional texts and media. In C. Surkamp, & B. Viebrock (Eds.), Teaching English as a Foreign Language: An introduction (pp. 177-194). J.B. Metzler Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-476-04480-8_10

Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken (12th ed.). Beltz.

Nation, P. (2013). Materials for teaching vocabulary. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing materials for language teaching (2nd ed., pp. 351-364). Bloomsbury Academic.

Nikolajeva, M. (2014). Reading for learning: Cognitive approaches to children’s literature. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Thaler, E. (2012). Englisch unterrichten: Grundlagen, Kompetenzen, Methoden. Cornelsen.

Tomlinson, B. (2013). Comments on part B. In B. Tomlinson. (Ed.), Developing materials for language teaching (2nd ed., pp. 224-225). Bloomsbury Academic.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.