| Opening Windows to the World: Developing Children’s Intercultural Understanding through Picturebooks in Japan

Alison Hasegawa, Emily MacFarlane, Martin Sedaghat and Karen Masatsugu |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This article explores intercultural learning activities created as part of a picturebook exploratory practice project in Japan. It was carried out with learners of English in three different educational settings: a preschool, a state primary school and an out-of-school picturebook read-aloud group. Learner responses to three focal picturebooks were collated through class work, artwork and informal observations, before, during and after picturebook read-alouds. Our reflections on these responses indicate that if children are given opportunities to actively discover cultural aspects through the picturebook vehicle, this could foster various positive attitudes. These include awareness of cultural differences, willingness to participate in intercultural encounters and starting to see things from different perspectives. We conclude that the use of picturebooks not only stimulates children’s initial interest in different cultural contexts but through their engagement with certain activities can lead to increased open-mindedness, and ultimately facilitate a deeper understanding of aspects of their own and other cultural identities.

Keywords: English learning in Japan, exploratory practice, intercultural understanding, picturebooks

Alison Hasegawa (previously Nemoto) has been teaching English in Japan since 1989. She has an MA in TEYL and has extensive experience of using picturebooks in ELT contexts. After teaching at Miyagi University of Education for a decade, she is currently an English teacher and teacher educator at several universities in Tokyo.

Emily MacFarlane is a teacher of English with over twelve years’ experience in primary schools. She recently completed an MA in TESOL and currently teaches at several universities in Sendai, Japan. Her research focuses on effective scaffolding techniques for picturebook read-aloud sessions.

Martin Sedaghat has been teaching English at a variety of levels in Niigata, Japan since 2003, and has been a preschool teacher since 2018. He is currently undertaking an MA in TESOL. His research interests include using picturebooks and game design.

Karen Masatsugu has been teaching English in Japan for 35 years and has an MSc in TESOL. She has been using picturebooks in language teacher education at Kwassui Women’s University since 2002 and runs an English picturebooks library on campus where student teachers hold read-aloud events.

Introduction: The Japanese Context

While many classrooms around the world are becoming increasingly multicultural and multilingual (Ellis, 2018), with children from diverse ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, Japan is often perceived as being an ethnically homogeneous country, characterized by monocultural, monolingual classrooms. In 2020, foreign residents accounted for 2.2% of the population (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2021), and a Ministry of Education survey showed only 93,474 non-Japanese children were registered as eligible to study at primary school, approximately 1.5% of the total for that age group (Japan Times, 2022). However, Japan is an important destination for immigrants from Asian countries, with growing numbers of students from various ethnic, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds entering the school system (Tokunaga, 2018). Often, children with hidden cultural diversity, including a foreign parent, grandparent, or roots in other countries are present in the classroom. While no data for the ethnicity of school students is available, 38,000 children in public primary and middle schools required assistance with Japanese in 2020, and the Ministry of Education estimates that 40,000 will need Japanese classes by 2026, suggesting a growing number of children attending Japanese schools who use languages other than Japanese at home (Kim, 2021).

Furthermore, Tsuda (2009) found that Japanese-Brazilian children whose families moved to Japan while they were young, faced strong assimilative pressures in Japanese schools and were not provided with opportunities to develop bilingual competence and a multi-ethnic or hybrid identity due to a lack of intercultural education. Several ethnographic studies (Ota, 2000; Shimizu, 2008; Tsuneyoshi, 2001) similarly found that these assimilative pressures along with the valuing of homogeneity have prevented students from adapting to Japanese schools. Tokunaga (2018) also suggests that the tendency to focus on equality, cooperation and community in Japanese schools can lead to teachers ignoring diversity. Moreover, it is rare for mainstream public schools to provide an education that affirms the culture and traditions of immigrant students (Tokunaga, 2018). Therefore, as Japanese schools are becoming more culturally diverse it is increasingly important for educators to give learners opportunities to learn about cultural diversity and engage with different cultural groups. This prompted an exploratory practice project to investigate how activities created around picturebook read-alouds, including the plot and the characters, could help develop children’s intercultural understanding.

Theoretical Framework

English in primary and pre-primary education

In Japan, ‘the ability to speak and understand English is widely regarded as essential for communication in a “globalized” world’ (Abe, 2013, p. 46). In the past decade, English education has experienced a major overhaul as the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) introduced a number of changes including lowering the starting age of mandatory English lessons by two years and doubling the amount of English for Years 5 and 6 in 2020. Currently, English is a formally assessed subject in Years 5 and 6 (70 hours a year), while ‘Foreign Language Activities’ (FLA) are taught in Years 3 and 4 (35 hours a year). In addition, according to data collected by Benesse (2019), 62.4% of private kindergartens and 66.4% of private accredited nursery schools provided some English language activity (Takizawa, 2021) although there are no guidelines or curriculum for preschool English in Japan. Also, there has been an expansion of immersion and international preschools, and many primary school children attend private English cram classes after school and English conversation clubs (Jin & Cortazzi, 2019).

Along with introducing English in primary schools, developing students’ ‘global outlook’ is an important aim of the new English curriculum (Nemoto, 2018) with MEXT guidelines stating that teaching materials for Years 5 and 6 should focus on people’s lives and cultures around the world. This is to deepen learners’ understanding of and interest in diverse cultures and ways of thinking, increase their awareness of themselves and cultivate a spirit of ‘international cooperation’ (MEXT, 2020, p.10). However, these guidelines do not promote an intercultural perspective in the sense of students seeing themselves as belonging to an intercultural environment. This article will examine if increased intercultural understanding can be facilitated using picturebooks in English language classes through English as a medium, rather than focusing on language learning as a primary goal.

Picturebooks and intercultural understanding

Ibrahim (2020, p. 13) highlights the ‘manifold benefits of using picturebooks with young children in early language learning’ including the development of wider educational goals such as intercultural understanding. And according to Mourão (2015, p. 203), picturebooks bring the ‘cultures of many Englishes to our classrooms’, motivating and supporting learners ‘to look beyond their own worlds and positively experience others’. Such scholarship shows how picturebooks can be a rich resource for English language teachers who seek to nurture learners’ intercultural understanding with authentic input, unique points of view and glimpses into new cultural contexts.

In Europe, there is an established tradition of using picturebooks for intercultural learning. An early example of this is The European Picture Book Collection (EPBC; http://www.ncrcl.ac.uk/eset/index.asp), an online resource for teachers to help children from different European countries to learn more about each other, discuss differences and similarities, and to improve linguistic, literary and cultural understanding ‘through reading the visual narratives of carefully chosen picture books’ (The European Picture Book Collection, n.d.). A more recent example of picturebook use for intercultural learning in ELT is the three-year Erasmus+ teacher education project, Intercultural Citizenship Education through Picturebooks in Early English Language Learning (ICEPELL). Underpinned by Michael Byram’s intercultural citizenship model, the ICEPELL project aimed to develop the five strands of attitudes, knowledge, skills of interpreting and relating, skills of discovery and interaction, and critical cultural awareness (Mourão et al., 2022).

When compared to such European contexts, use of picturebooks specifically for intercultural learning is new in Japan. A noteworthy early exception should be mentioned however, and this is Opal Dunn’s (2016) pioneering Dan Dan Bunko (International Children’s Libraries), established in 1977 to provide English picturebooks for multilingual Japanese children, though largely concentrated in Tokyo and uncommon in state schools. And while picturebook use in the English classroom is encouraged by MEXT (2018), teachers often have limited access and insufficient pedagogical techniques beyond just ‘reading the story’ (Hasegawa, 2021, p.387). Many teachers use read-alouds as a separate activity at the end of lessons if there is extra time for enjoyment (Kaneko, 2020) rather than integrating them into the curriculum. Furthermore, picturebook scholarship in the Japanese context has focused on students’ motivation and interest in English (Kanayama, 2021), with scarce research into intercultural learning. However, a recent empirical study by Burri et al. (2022) based on an almost wordless Australian picturebook had an explicit intercultural focus. The study’s aim was to explore how six Japanese primary learners interpreted stories from cultural contexts other than their own. The findings shed light on both intercultural understanding and misunderstanding encountered by the children as they made meaning across cultural groups in English.

Research Context

Our exploratory practice project aimed to address a gap in the scholarship in the Japanese context and has been shaped by our own classroom experiences, which have made us keenly aware of the significant potential of picturebooks for ELT with children (Mourão, 2015). As the title of this article indicates, we selected picturebooks that can act as windows, and possibly sliding doors, into more diverse settings for Japanese learners, as well as mirrors for learners who do not see their realities reflected in their learning materials (Sims Bishop, 1990). When selecting an appropriate pedagogical framework for the project, we drew on Benthien’s checklist (2021) for promoting intercultural understanding in schools and L2 classes, based on its focus on the Japanese school context. We applied the framework directly to the use of our focal picturebooks, and this is a conscious departure from widely used government-approved coursebooks. We rejected heavy dependence on coursebook texts due to their focus on surface level cultural areas such as food, festivals and clothing. As Benthien maintains, lessons should extend beyond cultural knowledge and instead, should embrace the following six aspects:

- fostering awareness of how one’s own culture and other cultures operate

- encouraging willingness to seek and participate in cross-cultural encounters

- building communication and interpersonal skills

- encouraging curiosity and open-mindedness about other cultures

- developing empathy, flexibility, tolerance, and the ability to see things from different perspectives

- being mindful of cultural differences. (p. 30)

She further suggests that links to the dynamic nature of culture can be made by raising children’s awareness and encouraging booktalk in English and the learners’ languages, as well as through carefully designed tasks. We agree that picturebooks are an ideal springboard for meaningful booktalk about cultural diversity and that they can facilitate the design of a variety of engaging tasks for children learning English.

During the project, we decided to implement dialogic approaches (Ghosn, 2013) which encourage learners to interact with the picturebook, for example by pointing to pictures, making predictions and commenting during the read-aloud – supported by well scaffolded pre- and post-reading tasks. This article presents three classroom reports based on lessons targeted at developing intercultural understanding aligned with Benthien’s checklist. Each report will describe the teaching context, choice of focal picturebook and profile of the learners. This will be followed by a rationale for the lesson content and a discussion of our observations and reflections. Finally, learner responses will be considered collectively in terms of the six areas of Benthien’s checklist.

Classroom Report 1: Preschool

The first focal picturebook, This is How We Do It: One Day in the Lives of Seven Kids from Around the World (Matt Lamothe, 2017) was chosen for the themes of similarities and differences between the daily lives of children around the world and intercultural focus of fostering awareness of one’s own culture and other cultures.

Teaching context

This part of the project took place at a small private preschool in Japan. As well as twice-daily lessons, the English teacher attends school all day and so can play with the children, join their walks, eats lunch with them and shares picturebooks with them before nap time. Such regular exposure to English has been effective for developing the children’s language. The main goal of the language programme is for the class shown in Table 1 to discover language, not be afraid to make mistakes and begin to sense the world beyond school, the city and Japan.

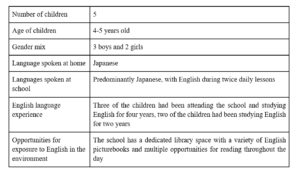

Table 1. Preschool Class Profile

Focal picturebook

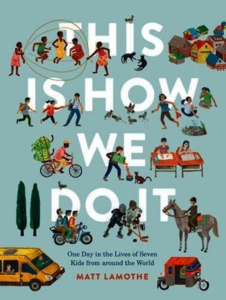

A picturebook was selected to help broaden the learners’ view of the world in an age-accessible context. There are many picturebooks that present famous aspects of countries such as landmarks, animals or cuisine, but these hold little meaning for the pre-primary learners who have an extremely limited connection to countries outside of Japan. Matt Lamothe’s (2017) This Is How We Do It: One Day in the Lives of Seven Kids from Around the World (Figure 1) was selected because of its straightforward design with uncluttered and easily recognizable illustrations, logical organization and the main topic is interesting and approachable for the target age range.

Figure 1. Front Cover of This Is How We Do It: One Day in the Lives of Seven Kids from Around the World

The picturebook depicts the daily lives of seven children in India, Iran, Italy, Japan, Peru, Russia and Uganda with colourful, clear illustrations laid out in a large format. Each opening focuses on a specific aspect of their lives, including what each child eats for breakfast, what their classroom looks like, how their names are written, how they play with their friends after school and how they help their families with chores at home. This design fosters concentration on one point at a time so that observations and questions can smoothly lead into learner-centred booktalk about each section. Though it focuses only on ‘traditional’ family structures, This Is How We Do It provides a window into the lives of different children, helping child readers to notice not only the differences but also the similarities with their own lives. Additionally, it connects well to a number of post-reading activities so learners can reflect on what they have seen to create their own visual projects.

Lesson content: 10 minutes per opening (one per week)

Pre-reading

- Learners were shown a world map, country flag flashcards and short videos to practice and learn the names of different countries and their traditional greetings.

- Pictures of classrooms and school settings in different countries were then shared with learners and their comments and observations were encouraged.

During reading

- This Is How We Do It was shared with learners over several months, one opening and topic per week. Previous pages were reviewed with short quizzes on the names and daily habits of the children in the book to check comprehension and memory. Each opening was shown first without teacher explanation, and learners were invited to predict each topic.

- The text was read aloud with questions to promote booktalk. Emphasis was on aspects that might be similar or different from the children’s own lives.

- Learners were asked to predict what the following topic might be and what else they would like to know about the children in the book.

Post-reading

- Learners were given folders to create their own books about themselves and encouraged to decorate these.

- After each weekly reading, children were given a page with a short prompt to fill in and a space for drawing a picture. These prompts were based on topics from the picturebook, such as ‘My house,’ ‘My breakfast’ and ‘My school’ (see Figure 2).

- After finishing a page, learners put it into their folder and were given time to look at their books. The books were periodically shown during lessons to let students talk about their drawings and to notice the differences and similarities between their own lives and those of their classmates (see Figure 3). When the books were complete, the children took them home to share with their families.

Figure 2. Page from learner-made book about themselves

Figure 3. Learners sharing and organizing the pages of their books

Reflections

The main goal of this part of the project was to show children that while there are many things that differentiate cultures, there are far more that unite us. This Is How We Do It was particularly effective in helping the learners to view themselves through the window of the daily lives and those of their classmates. In terms of Benthien’s checklist, they were able to notice numerous aspects of their own cultures and children in other countries. Additionally, learners showed increased interest and curiosity such as about how children travelled to school, helped their families and spent time with friends. Comments from the children in Tables 2 and 3 were made about the differences, such as breakfast menus and writing systems, but the majority were observations about similarities, such as games, sports and helping at home.

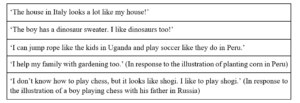

Table 2. Learner comments regarding differences [translated from Japanese]

Table 3. Learner comments regarding similarities [translated from Japanese]

The learners were particularly interested in the last two openings, which end with a double-page spread illustration of the night sky to show that no matter who or where we are, we see the same stars and moon. This is followed by an opening with photographs of each of the seven children and their families. For some learners, this was a surprise to fully realise that all the people they had been reading about for months were real. This discovery informed subsequent readings of the book as the children could make even stronger connections to the illustrations with the knowledge that these represented actual children just like them. One difficult aspect of using this picturebook was that the seven children described were all slightly older than the learners in the class, so there were unfamiliar elements of primary school life, such as coursebooks, homework and uniforms. However, the older children in the preschool are preparing to transition to this stage, and it was a useful opportunity for discussion about the challenges of growing up, no matter where you are.

Classroom Report 2: Primary School

The second focal picturebook, Alma and How She Got Her Name (Martinez-Neal, 2018) was chosen for the themes of identities, names and naming traditions and intercultural focus of fostering awareness of one’s own cultural identity and other cultural identities.

Teaching context

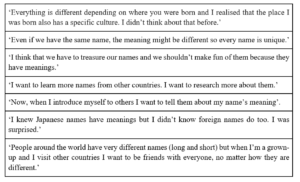

The primary school where this part of the project took place is one of the largest in the district, drawing from a sizable catchment area with over 1100 students. It serves a historically socio-culturally disadvantaged area and students tend to perform lower on national tests than other schools within the same Board of Education. Learners at this school are, at times, unmotivated with a negative attitude towards English which they often see as unconnected to their everyday lives. For Years 5 and 6, English is taught for at least two forty-five-minute classes a week using one of seven coursebooks approved by MEXT. One lesson in every eight (about once a month) focuses on exploring different nations around the world. This class was based on naming customs in multiple countries with Saudi Arabia, the USA and Vietnam mentioned specifically. It was felt that when using only the coursebook, students did not connect with the material meaningfully, as their main take-away was that traditions from other countries were ‘different’. It was proposed that a picturebook on the same topic could spark interest and encourage the children profiled in Table 4 to think more deeply.

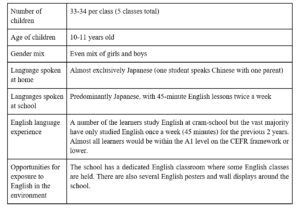

Table 4. Year Group Profile

Figure 4. Front Cover of Alma and How She Got Her Name

Focal picturebook

When brainstorming the topic of names, several picturebooks were considered such as The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi (2001) and The Change Your Name Store by Leanne Shirtliffe (2014). These stories depict characters who, unsatisfied with their name, try out many different options before finally realising the importance and uniqueness of the name they were given. However, as the aim was to encourage learners to think about aspects of their own and other cultural contexts, it was important that not only names but naming traditions and the meaning behind the name of the protagonist was explored. This led to the selection of Juana Martinez-Neal’s (2018) Alma and How She Got Her Name (see Figure 4).

In this picturebook, Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela believes that her name does not fit, not on paper or to her as a person. The child reader follows Alma as her father tells her about her name, the family member each part represents, as well as their interests and personalities. The graphite, soft pink and blue coloured pencil illustrations create the warm feeling of an old family album as we are transported into Alma’s imagination while she listens to her father’s descriptions. Each page turn brings a new relative for Alma to meet and connect with, finding similarities with each of her ancestors. Finally, she decides that her name not only tells the story of her past but also who she is now, making it the perfect fit. On the last page the reader is asked, ‘What story would you like to tell?’ This helps children think about their own name and what it means.

Lesson content: 30 minutes (within a 45-minute lesson)

Pre-reading

- Learners were shown some of Picasso’s paintings and asked if they knew his full name which contains 23 words (Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Martyr Patricio Clito Ruíz y Picasso). The class read his name together and enjoyed trying to see how much of it they could remember in one attempt.

- The learners shared their first impressions of his name (‘too long,’ ‘annoying,’ ‘strange’) before trying to guess the meaning behind his numerous names. The majority predicted that he had chosen his own name as a kind of ‘stage name’ to become more famous.

- With the learners’ curiosity piqued, the picturebook was introduced to help clarify Picasso’s full name.

During reading

- The picturebook was displayed on a large screen using a document camera so that everyone could easily see the images.

- Due to limited class time, the story was read aloud once slowly with limited questions from the teacher. Even without prompting, the learners still commented frequently on the characters and how they related to them.

- Some of the English in the book was explained or simplified to fit the learners’ level, for example the double meaning of Alma’s name not ‘fitting’ was explained as ‘It’s too long. I don’t like it. It’s not me.’

- Learners were encouraged to guess the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary, such as words for family members and then, the teacher confirmed or clarified these words.

- At the end of the story, when Alma expressed that her name was her history, learners were keen to relate that concept to both Picasso and themselves.

Post-reading

- As with the pre-reading activity, the learners were asked to guess the meaning behind Picasso’s long name. This time they were able to successfully guess that his parents had named him after family members (as well as saints).

- Learners were again asked to share their impressions of his name and if it had changed (‘It’s interesting. I understand it now.’).

- To explore other naming traditions around the world, the relevant section in the coursebook was used. The learners were asked to compare names from Saudi Arabia, the USA and Vietnam to their own, considering not only differences but also similarities.

- Then, the last page in the picturebook which asked, ‘What’s your story?’ was re-read. Both the English teacher and the Japanese homeroom teacher shared the meanings behind their own names followed by learners who were willing to share.

- Finally, the learners completed reflection sheets and the children who did not already know the meaning behind their names were encouraged to ask their family members.

Reflections

During the class, the main focus had been on fostering awareness of aspects of one’s own cultural context and other contexts with a particular emphasis on naming traditions. After the class, reflections from the Japanese homeroom teachers showed that they believed the picturebook had helped the learners connect with the subject and understand more deeply than in their previous years’ classes. This was also mirrored in the learners’ reflection sheets where they discussed what they had learned about names around the world. In the past, learners often only wrote that they had learned that non-Japanese names were different or that they had noticed that in other countries the first name/surname order was reversed. While these kinds of comments were also evident this year, learners’ reflections showed that they had thought more deeply about the meaning of names as well as Japanese naming traditions, as can be seen from some of their comments in Table 5.

Table 5. Learner comments on names and naming customs [translated from Japanese]

Overall, although the set curriculum limited the amount of time available for booktalk and post-reading activities, the use of Alma provided learners with deeper connections than the coursebook. It not only increased their interest in and understanding of names and naming traditions around the world but also provided time for reflection. While finding a suitable picturebook to connect to cultural themes in set coursebooks is a challenge, the benefits of supplementing in this manner are clear. In this case, the picturebook was not only a window onto other cultural contexts but also a mirror which helped the children to reflect on their own.

Classroom Report 3: English Picturebook Read-Aloud Group

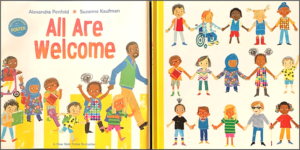

The third focal picturebook, All Are Welcome (Penfold, illust. Kaufman, 2018) was chosen for the themes of school routines and school cultures around the world and intercultural focus of encouraging curiosity and open-mindedness about other cultures.

Teaching context

The third part of the project took place at a local community centre where an informal monthly read-aloud group meets. The group profiled in Table 6 was established three years ago to provide primary learners the opportunity to enjoy picturebooks and collaboratively participate in activities through English, such as artwork or drama. The learners are from different primary schools but are quite familiar with each other and work well in pairs or small groups. Prior to this session, It’s Okay To Be Different by Todd Parr (2001) had been shared and social and emotional learning was explored by reading The Color Monster – A Story about Emotions by Anna Llenas (2018) and Glad Monster, Sad Monster by Ed Emberley and Anne Miranda (1997). Interestingly, these influences are also entwined in the artwork and comments during the session outlined below.

Table 6. Group Profile

Focal picturebook

This session was inspired by the discovery of All Are Welcome written by Alexandra Penfold and illustrated by Suzanne Kaufman (2018). This picturebook depicts a regular school-day in New York for a group of diverse children and their families and acts as a window into a different world for Japanese children, one where each person’s uniqueness is celebrated, and differences enrich the school community. The message is reflected both in the text, ‘Our strength is our diversity,’ and in the illustrations depicting children with disabilities as well as varied family structures with a range of sexual orientations and ethnicities. This picturebook was considered ideal as a vehicle to address Benthien’s emphasis on encouraging curiosity and open-mindedness about other cultural contexts.

The learning outcomes for this session were to recognize similarities and differences in school routines and school cultures around the world, to encourage informed and positive reactions to different ethnicities by the learners, and initiate conversations about physical and cultural differences, such as skin tones and head coverings. The beautiful poster included inside the dust jacket inspired the post-reading activity: to create original welcome posters and to prompt open-mindedness toward different ethnicities after reading the picturebook.

Figure 5. Dust jacket (left) and front cover (right) of All Are Welcome

Lesson content: 90 minutes

Pre-Reading

- Learners were shown the picturebook It’s Okay To Be Different by Todd Parr, read together in the previous session, so that they would be reminded of the message that people do not look similar or act in the same way.

- After this, the front cover of All Are Welcome was shown to the learners, without the dust jacket (see Figure 5), thus concealing the title until later. The teacher explained that it is also a book about difference and depicts a day at school for children of many different ethnicities, abilities and disabilities.

- The teacher then set a short discovery activity in groups for the children to explore a page of the picturebook by circling similarities and differences on a colour copy of one of the openings. The leader of each group, an older child, also recorded the items in Japanese.

During Reading

- Learners were shown the front cover again and asked for their observations. They quickly noticed someone who uses a wheelchair and someone with a visual impairment. When attention was drawn to the skin tones by the teacher, the learners said the children depicted were ‘foreigners’ from other countries, some with dark skin and some with lighter skin. When asked what country this could be, they immediately guessed the USA. The learners were asked to think of a title for the picturebook as they listened to the initial read-aloud.

- The second read-aloud was slower and mediated in both English and Japanese. When an opening was reached that learners had focused on in the pre-reading activity, that group excitedly joined in and shared their discoveries.

- On different pages the picturebook showed a hijab, patka or turban and a yarmulke and when the learners were asked if anyone at their school wore a head covering like this, they said no. Then, these words were introduced with photographs, so the learners could name each head covering. This gave the group the necessary support to use these new terms during the rest of the session. For example, towards the end, when they saw the girl wave goodbye to her friend, they could identify that she was wearing a hijab.

- The learners were asked to share their ideas for the title of the book and suggested, ‘We are all friends.’ ‘Let’s play together!’ and ‘Everyone is different and that’s okay.’ Finally, the teacher showed the group the dust jacket and confirmed the title, All Are Welcome and showed them the beautiful poster inside.

Post-Reading

- Next, the learners were set a task of making posters to welcome people to the community centre where their group meets. The words ‘All Are Welcome Here!’ in English and Japanese were already printed on a large piece of paper, and the children were invited to use colours, designs and images to personalize it.

- Before they started, the teacher provided packs of Crayola crayons, called ‘Colors of the World,’ which include 24 different skin tones. This resource helped learners add various skin tones to their posters and they were excited to use all of these.

- Each group worked on their posters for 30 minutes before presenting them. They also shared what they had learned.

Reflections

In this section, two of the four welcome posters produced by the learners will be considered. Although the posters were created based on the same picturebook and booktalk, each one is original and quite detailed.

Figure 6. Group 1’s poster – created after reading All Are Welcome

Group 1 did not add colour to the central message (see Figure 6), but their poster depicts a total of 22 people, of different genders with a variety of skin tones. It also has a robot, an alien and a giraffe, all holding hands. This group said that their main aim was to show many different people getting along and standing side-by-side.

Figure 7. Group 4’s poster – created after reading All Are Welcome

In Group 4’s poster, seven faces are drawn around the central message (Figure 7), also variously coloured. The faces represent different skin tones and genders, and different emotions (anger and sadness) and disabilities (two have dark glasses). The previous work with The Color Monster – A Story about Emotions and Glad Monster, Sad Monster had influenced this poster because it includes the range of emotions we focused on. This group added a message in Japanese that when translated means, ‘Don’t be nervous, there are many different people here’. This group said that their main aim was to add both happy and sad faces, because many different people will come to the community centre, but everyone is welcome. Both of these posters indicate the learners’ open-mindedness about other cultures after reading the picturebook, as communicated through their design choices. Other comments also indicate the learners’ change in attitudes, ‘We discovered that there are many different people around the world’, ‘We noticed that having friends is a precious gift’, and ‘It looks fun to have a school with so many different children’.

Discussion

In this discussion, additional learner responses from the three classroom reports will be considered in terms of Benthien’s checklist of six intercultural areas. Our goal is to show other teachers how this framework can be utilized for the initial design of classroom activities within an exploratory practice approach.

Fostering awareness of how one’s own and other cultural contexts operate. Learners from Classroom Report 1 made numerous observations of differences between their everyday traditions and those of the children in the book, but overall, their reflections on the similarities quickly outnumbered them. It was observed that the picturebook Alma and How She Got Her Name helped learners to not only become aware of naming traditions from other cultures but also to consider Japanese naming customs for the first time. Learners had not previously realised that names written in the Roman alphabet (rather than kanji which represent Japanese names and can have multiple interpretations) could have meaning behind them. The read-aloud also prompted some learners to consider the meaning behind their own name.

Encouraging willingness to seek and participate in cross-cultural encounters. After reading All Are Welcome, responses to the question ‘Do you want to visit this school?’ indicated a positive impact. Some said, ‘Yes, because they all look so friendly’. and others said, ‘Yes, we want to go, because there are children from different countries around the world’. Similarly, in Classroom Report 2 learners expressed a desire to include their name’s meaning when they introduce themselves to non-Japanese people for the first time, while other learners expressed a desire to be friends with anyone, no matter what their name is.

Building communication and interpersonal skills. Learners in all three projects displayed interpersonal skills such as ‘showing respect’ and ‘understanding the feelings of others’. When they shared their mini books about themselves with classmates, the learners from Classroom Report 1 used a variety of communication skills including listening to others, asking questions and giving feedback. During the session in Classroom Report 3, learners worked together collaboratively by completing various tasks within time limits through effective communication. Learners in Classroom Report 2 also practised in this way when they shared the meaning behind their own names with their classmates.

Encouraging curiosity and open-mindedness about other cultural groups. After reading This Is How We Do It, learners became more observant of and interested in the smaller details of other cultural settings. Whereas previously they had only been shown disconnected facts about foreign countries, such as popular foods and famous landmarks, they were more able to ask questions about aspects of daily life. Similarly, learners showed interest in All Are Welcome and keenly engaged in the task to find similarities or differences. The overall outcomes for this session were encouraging, in that the learners noticed and began to be able to talk about ethnicities, visible differences and displayed positive attitudes towards the multicultural context of the picturebook, they also added children of various ethnicities to their welcome posters and said that they wanted to visit such a school in the future.

Developing empathy, flexibility, tolerance, and the ability to see things from different perspectives. When they reflected on Alma and How She Got Her Name, learners showed that while they previously might have made fun of names that were different or strange, they had realised that names should be treasured. Similarly, after reading All Are Welcome, tolerance was indicated through comments such as, ‘There are children who are different to us and that’s okay’ or ‘There are different people around the world and that’s fine’. Interestingly, these comments seem to have been influenced by their work with a previous picturebook, It’s Okay To Be Different. Work with picturebooks with similar themes as a text ensemble can therefore strengthen such messages, and this might be reflected in behaviours and attitudes of learners in the future.

Being mindful of cultural differences. When learners from Classroom Report 1 were first introduced to This Is How We Do It they made comments about the children and their homes being ‘strange’, but as they became familiar with the book and learned more about each person, their observations were positive and inclusive. While learners were originally only able to see Picasso’s name as ‘strange’ and ‘too long’, after their work with Alma they were able to understand more about naming traditions and to appreciate more nuanced meanings.

Conclusion

This exploratory practice project has shown how three different picturebooks used within an interculturally-orientated pedagogical framework deepened learners’ intercultural understanding in our pre-primary and primary English language classrooms in Japan. Our observations indicate that the interactive work with the selected picturebooks and the accompanying activities were successful during the process of ‘noticing and talking about similarities and differences to a child’s own cultural surroundings’ and helped learners take an initial step on their journeys to ‘develop cultural literacy, a first step in intercultural learning’ (Ellis, 2018, p. 85).

For the Japanese learners in the project, the focal titles acted as a window to another world, and because the view is that of children’s school and home lives, or their given name, they could start to draw comparisons and relate to familiar aspects, while at the same time wonder and discover the unfamiliar. The use of carefully selected picturebooks created opportunities for meaningful discourse about culture and these were a powerful tool in our project. We recommend that English teachers globally likewise open their classroom windows to the world.

Bibliography

Choi, Yangsook (2001). The Name Jar. Dragonfly Books.

Emberley, Ed and Anne Miranda (1997). Glad Monster, Sad Monster. Little, Brown and Company.

Lamothe, Matt (2017). This Is How We Do It: One Day in the Lives of Seven Kids from Around the World. Chronicle Books.

Llenas, Anna (2018). The Color Monster – A Story about Emotions. Little, Brown and Company.

Martinez-Neal, Juana (2018). Alma and How She Got Her Name. Candlewick Press.

Parr, Todd (2001). It’s Okay To Be Different. Little, Brown and Company.

Penfold, Alexandra, illus. Suzanne Kaufman (2018). All Are Welcome. Alfred A. Knopf.

Shirtliffe, Leanne, illus. Tina Kügler (2014). The Change Your Name Store. Sky Pony.

References

Abe, E. (2013). Communicative language teaching in Japan: Current practices and future prospects. English Today, 29(2), 46-53.

Benesse Educational Research and Development Institute (2019), 第3回幼児教育・保育についての基本調査 [Third Basic Survey on Early Childhood Education and Care]. Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://berd.benesse.jp/jisedai/research/detail1.php?id=5444

Benthien, G. (2021). Simple ideas and strategies for promoting intercultural understanding in schools and L2 classes. The Language Teacher, 45(2), 29-34.

Burri, M., Mantei, J, & Kervin, L. (2022). ‘This side is the real world and the other one is like Minecraft’: Using an almost wordless picture book to explore Japanese primary school students’ cultural awareness. Language Teaching for Young Learners, 4(2), 192-214.

Dunn, O. (2016). Using picturebooks – Fifty pioneering years. C&TS Special Pearl Jubilee Edition, IATEFL Young Learners & Teenagers SIG, 20-23.

Ellis, G. (2018). The picturebook in elementary ELT: Multiple literacies with Bob Stake’s Bluebird. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8-18 year olds (pp. 83-104). Bloomsbury.

Ghosn, I. (2013). Humanizing teaching English to young learners with children’s literature. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 1(1), 39-57.

Hasegawa, A. (2021). Exploring the potential and the power of interactive picturebook read-alouds in the EFL classroom. Bulletin of Miyagi University of Education, 56, 385-395.

Ibrahim, N. (2020). The multilingual picturebook in English language leaching: Linguistic and cultural identity. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 8(2), 12-38.

Japan Times. (2022, March 25). Education status unknown for 10,000 eligible foreign children in Japan. The Japan Times. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2022/03/25/national/education-foreign-children-survey/

Jin, L. & Cortazzi, M. (2019). Early English language learning in East Asia. In S. Garton, & F. Copland (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of teaching English to young learners (pp. 477-492). Routledge.

Kanayama, K. (2021). 絵本の読み聞かせが小学校英語の目標達成に与える影響 : 国内研究を中心にしたレビューから[Effects of picturebook reading on the achievement of English education goals in elementary school: Literature review of previous studies in Japan]. 北海道教育大学紀要. 人文科学・社会科学編 [Journal of Hokkaido University of Education (Humanities and Social Sciences)], 71(2), 93-106.

Kaneko, T. (2020). Picture stories in Japanese elementary school English classrooms: A comparison of the use of picture stories in Japan and three English speaking countries. 学苑・英語コミュニケーション紀要 [Gakuen English Communication Journal], 954, 2-14.

Kim, C. (2021, September 15). Expat children in Japan risk falling behind in Japanese lessons. Nikkei Asia Online. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-immigration/Expat-children-in-Japan-risk-falling-behind-in-Japanese-lessons

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [MEXT]. (2018). Let’s Try! 1 Shidou-hen [Let’s Try! 1 Teacher’s Manual]. MEXT.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [MEXT] (2020). The National Curriculum Standards for Grade 5 and Grade 6 in Elementary School, Section 10 Foreign Languages. https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20201218-kyoiku01-000011246_2.pdf

Mourão, S. (2015). The potential of picturebooks with young learners. In J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to young learners: Critical issues in language teaching with 3-12 year olds (pp. 197-217). Bloomsbury Academic.

Mourão, S., Kik, N., & Matos, A. G. (2022). From culture to intercultural citizenship education. In ICEPELL Consortium (Eds.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 22-30). CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

Nemoto, A. (2018). Getting ready for 2020: Changes and challenges for English education in public primary schools in Japan. The Language Teacher, 42(4), 33-35.

Ota, H. (2000). Nyukama no kodomo to Nihon no gakko [Newcomer children and Japanese schools]. Kokusai Shoin.

Shimizu, K. (2008). Koukou wo ikiru nyukama: Osaka furitsu koukou ni miru kyoiku shien [Newcomers in high schools: Educational support in Osaka prefectural high schools]. Akashi Shoten.

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix-xi. Retrieved June 26, 2022, from https://fall15worldlitforchildren.wordpress.com/mirrors-windows-sliding-glass-doors/

Statistics Bureau of Japan (2021, December 28). News Bulletin December 28, 2021. Statistics Bureau of Japan. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/info/news/20211228.html

Takizawa, H. (2021). Youchien no nennchuu kurasu ni okeru shounichi no eigo jyugyou. [The first English class for four-year-old children at a kindergarten: How English is taught and how children acquire English]. Annual Report of the Faculty of Education, Gifu University. Teacher education and educational research, 23, 105-114. http://repository.lib.gifu-u.ac.jp/bitstream/20.500.12099/81443/1/edu_180023013.pdf?fbclid=IwAR35z2OGaG8Y3R5WE9FSye2bbGJ34z2zMK_oo2OZWkyANh8XciIGVw9w8V8

The European Picture Book Collection. (n.d.). Introduction. http://www.ncrcl.ac.uk/eset/intro.asp

Tokunaga, T. (2018). Possibilities and constraints of immigrant students in the Japanese educational system [Paper commissioned for the 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report, Migration, displacement and education: Building bridges, not walls]. UNESCO Publishing. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266211

Tsuda, T. (2009). Japanese-Brazilian ethnic return migration and the making of Japan’s newest immigrant minority. In M. Wiener (Ed.), Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity (pp. 206-227). Routledge.

Tsuneyoshi, R. (2001). The Japanese model of schooling: Comparisons with the United States. Routledge Falmer.