| Creating and Presenting Mash-up Stories in the English Language Classroom in Japan

Suzanne Kamata |

Download PDF |

Abstract

The New Japanese Course of Study set forth by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology calls for the implementation of the Active Learning methodology in English and other foreign language classes, including interactive discussions among students, debates, and presentations. While the guidelines advocate for integrated linguistic activities, they do not emphasize creativity. Storytelling, however, offers opportunities for students to develop communicative skills, increase vocabulary, and is often highly motivating. As a group activity, storytelling can help students cultivate many of the skills set forth as goals by governmental guidelines, including a familiarity with technological devices. This paper introduces an assignment in creating multimodal mash-up stories – a combination and/or adaptation of two existing stories – which was carried out at a Japanese university. Students were asked to combine a well-known Japanese story with a non-Japanese fairy or folktale, and then present it in the manner of their choosing. For example, members were allowed to act out the stories, present them as kamishibai, or PowerPoint presentations, or create videos, among other methods. I will show that although students may be unfamiliar with writing stories in English, with sufficient scaffolding, and with access to their full linguistic repertoire, they are capable of combining familiar texts in meaningful and original ways, while developing an understanding of story structure. The activity also allows students to collaborate, employ critical thinking skills, and capitalize on the individual strengths of group members. Furthermore, students are given the opportunity to make comparisons between cultures and express their creativity.

Keywords: mash-up stories, storytelling, ELT, Japan, translanguaging

Suzanne Kamata is from the USA, with an MFA from the University of British Columbia. She has been teaching English in Japan to learners of various ages since 1989. She is an associate professor at Naruto University of Education, and the author of several children’s books, as well as books for adult literacy learners.

Introduction

Storytelling is necessary in our daily lives, and is employed in various fields such as business (Barker & Gower, 2010; Denning, 2006; Monarth, 2014), medicine (Charon, 2005; Ofri, 2005), law (Massaro, 1989; Rideout, 2008), and engineering (Lloyd, 2000; Adams, et al., 2007). In addition to being essential for all speakers of English, it is also an important competence for English Language Learners (Kiernan, 2005). As Amy Shuman (2005) writes, ‘Storytelling is pervasive in ordinary conversations’ (p. 6). Furthermore:

Storytelling promises to make meaning out of raw experiences; to transcend suffering; to offer warnings, advice, and other guidance; to provide a means for travelling beyond the personal; and to provide inspiration, entertainment, and new frames of reference to both tellers and listeners (Shuman, 2005, p. 1).

In Japan, English language teaching (ELT) has traditionally been geared toward preparing students for difficult and competitive entrance exams to high schools and universities. Teachers must make their way through government-approved coursebooks and may feel that there is no extra time for indulging in encouraging students to tell and write stories, which are not tested in the exams that will determine the trajectory of their students’ lives. Nevertheless, educational guidelines put forth in the Second Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education (MEXT, 2017) call for the development of competencies for independence, collaboration, and creativity, all of which can be fostered through storytelling. Furthermore, guidelines appeal to instructors to ‘increase the number of classes with an emphasis on balancing the attainment of knowledge and skill with thinking capacity, decisiveness, and expressiveness’ (MEXT, 2011b., p. 5).

Translanguaging in Japan

In recent years, the concept of translanguaging has been widely discussed in the field of bilingualism research (see, for example, Canagarajah, 2011; Garcia & Wei, 2014; Hornberger & Link, 2012). This theory posits that “named languages” (for example, Japanese, English, Arabic, German) are comprised of linguistic features that pertain to a single, expanded linguistic system, which users can draw upon as necessary. Garcia (2009) defines translanguaging as ‘multiple discursive practices in which bilinguals engage in order to make sense of their bilingual worlds’ (p. 45). As Pacheco and Miller (2015) point out, ‘Translanguaging pedagogies encourage emergent bilinguals to use the full range of their linguistic repertoires when making meaning in the classroom’ (p. 533).

In Japan, Japanese has been the traditional language of instruction in English Language classes (Terauchi, 2017); however, Japan’s Ministry of Education, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) mandated monolingual instruction in English (L2) courses in order to maximize students’ exposure to the language (MEXT, 2011a). In actuality, however, Japanese is still used to a certain extent in ELT (Turnbull, 2018). Research on translanguaging in Japan suggests, in addition, that allowing the use of Japanese (usually L1) in class can be beneficial to student motivation (Yamauchi, 2018).

Storytelling and Creative Writing in a Japanese Context

Most Japanese students have little or no experience of writing creatively in junior high school and beyond in English or Japanese (Thompson, 2021). Having mostly been engaged in memorizing grammatical rules and translating texts from English into Japanese, they tend to be wary of activities in which there is no one correct answer. English-language creative writing teachers often introduce their students to Freytag’s pyramid, a story structure which involves an inciting incident, development or rising action, climax, and denouement (Salesses, 2021, pp. 55-68). Students are encouraged to follow this model, and are often persuaded that this is the ‘correct’ way to tell a story with the implication that other structures are wrong (Chavez, 2021; Hemley & Xi, 2021; Salesses, 2021). In North America, creative writing practitioners have tended to deem showing versus telling superior to the reverse, and eschew adjectives in favour of strong verbs, and value character-driven plots (Rozakis, 2004). However, the stories with which Japanese students are likely to be most familiar may follow a different plot structure in which conflict is not important. In addition, many students are avid readers of manga, and may be most accustomed to stories that continue over several years, and many episodes. As Asian American writer Mathew Salesses (2021) writes ‘There is no universal standard of craft’ (p. 101). These days, instructors must be aware of the dangers of imposing their own values on other cultures when insisting upon universal notions of craft. Thus, although it is arguable that the grammar-translation method still commonly used in Japan is outdated and ineffective, it is important to recognize cultural differences when introducing creative writing into the Japanese ELT classroom.

That said, students who have little or no experience with storytelling or creative writing, and perhaps limited foreign language skills, often appreciate a template. Instead of imploring them to create something from nothing, students are often encouraged to play with existing texts. Folktales, for example, are a potential starting point for creative writing. Many students are probably familiar with classic folktales from their native culture. In Japan, folktales are often included in Japanese and English coursebooks for elementary and junior high school students. For example, Sunshine 2 (Kairyudo, 2020), a coursebook widely used in second-year English classes in Japan, features Gon, the Little Fox, a traditional folktale about a fox who tries to apologize for stealing eels from a fisherman by secretly bringing him chestnuts. Thanks, in part, to the international popularity of Disney movies, many Japanese students are also familiar with the basic storylines of European folk and fairy tales such as Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, or even Aladdin, which was derived from a Middle Eastern folktale and has been presented as a musical, and in cinematic form, around the world.

Both European fairy tales and Japanese folktales tend to follow a three-act structure, which basically conforms to Freytag’s Pyramid. These similarities make it relatively easy to blend stories together. With scaffolding in place, students can expand upon the plot and characters. As Debnam (2023, para. 21) points out,

many traditional fairytales rely on two-dimensional, stereotypical characters: the villain is always 100% evil with no chance of redemption; girls are compliant, don’t have much agency and need rescuing; and the male characters are always sure of themselves, and heroic.

Fractured or twisted fairy tales are retellings which often give a modern spin to well-known stories, sometimes with a surprise ending. In addition to traditional stories, modern classics such as the Harry Potter books are familiar to most students and lend themselves to further creativity (Bland, 2018).

A Mash-up Storytelling Presentation

The Mash-up Storytelling Presentation, in which groups of students combine elements of existing stories to create a new story, was introduced as an in-class activity at a small teacher’s college in Japan. The students in question are first- and second-year undergraduate students in a general education English communication course. The class is a required course, with students specializing in different areas including Early Childhood Education, Art, Special Support Education, Japanese, and Physical Education, as well as English. There are generally between 19 and 25 students in each class, which meets once a week for 90 minutes, over 15 weeks. Occasionally, foreign students from countries such as Thailand and China engaged in study abroad are enrolled in these classes. The students have varying levels of English ability.

Before introducing the Mash-up Storytelling Presentation, one classroom period is spent reading and exploring various English-language picturebooks. The intention of this class is to give students the opportunity to communicate in English, acquire new vocabulary, and expose them to other cultural contexts. As these students are aspiring educators, it is my hope that they will also gain an awareness of picturebooks that they might use in class when they become teachers. Among the books shared are Little Orange Honey Hood (Cullen, 2018), a retelling of Little Red Riding Hood set in South Carolina, in which the wolf is replaced by an alligator, and the main character is Black girl journeying through a swamp instead of a forest (see Figure 1), and Angkat: A Cambodian Cinderella (Coburn & Flotte, 1998). Students are also shown one or two YouTube videos featuring readings of fractured folk and fairy tales, such as The Three Ninja Pigs (Schwartz & Santat, 2012).

Figure 1. Cover of Little Orange Honey Hood

Next, students are divided into groups of three or four students, and the instructor explains that they will be creating a mash-up story by combining a traditional or well-known Japanese story and a traditional or well-known story from another culture. As examples, students are shown a list of titles of well-known Japanese folktales such as Momotaro (Peach Boy), Urashima Taro, Omusubi Kororin (Rolling Riceball) and Saru Kani Gassen (The Crab and the Monkey) alongside titles of potentially familiar European fairy tales such as Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Little Pigs, and so on. If non-Japanese students are involved, they are encouraged to explore and incorporate stories from their own cultural backgrounds. Students are permitted to go to the library or use their devices to search online for folktales. In a recent class, one group of three male second-year students created a mash-up between Little Red Riding Hood and Momotaro in which Red girl exacts revenge on the wolf that ate her grandmother after receiving training from Momotaro, who is famous in Japanese lore for defeating a demon in battle (See Appendix 1).

Figure 2. Cover image of kamishibai created by students.

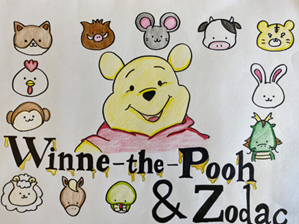

Some students choose to combine stories and characters from modern classics such as Winnie-the-Pooh (Milne & Shepard, 1926), which was mashed up with a traditional story about the animals of the Japanese zodiac, as can be seen in Figure 2. Hogwarts, the school setting of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, was employed in a story featuring the beloved doughnut-loving characters Bam and Kero from a series of Japanese picturebooks created by Yuka Shimada (see Appendix 2). Widely popular Japanese characters from television and manga such as Doraemon, a blue robot cat with time-traveling abilities, and Anpanman, a superhero with a head made from a bean jam bun, also appear in mash-up stories. Students are allowed class time to brainstorm story ideas in the language of their choice in order to take advantage of their full linguistic repertoire, and to decide how they will present their stories in English.

Multimodal Presentations

Although the instructor suggests options for presentation, the possibility for innovation remains. Some groups choose to act out their stories, while others create kamishibai, a traditional Japanese form of storytelling, illustrating the scenes on large cards which are shown one by one to the class. Others make puppets and fashion backdrops, such as the ones for a mash-up featuring Anpanman and Little Red Riding Hood as shown in Figure 3. Some have created PowerPoint presentations with recorded narration, or animated movies, sometimes with Japanese subtitles. These last two options can enable students who are anxious about speaking in front of others to share their work with the class.

Figure 3. Puppets and backdrop for mash-up of Anpanman and Little Red Riding Hood

To ensure accountability, each group is asked to report students’ individual roles. As they are working in groups, they will by necessity divide the labour. Typically, students will decide upon the story together. Then, one student will write the story – perhaps first in Japanese and then translate it into English – one or more students will create images to go with the story’s scenes, either by drawing them or using digital means, and another student will be in charge of technology, such as creating a PowerPoint presentation. For the in-class presentation, usually the students will take turns reading the text, or take on the roles of different characters. In this manner, they cover all four of the basic skills – reading, writing, speaking and listening – that they are expected to practice in class. This assignment also fulfils the incorporation of information and communications technology (ICT), which Japanese teachers are encouraged to use in their lessons.

Peer assessment

After each group presents its mash-up story, the other students are tasked with assessing their classmates’ presentations. They are given a simple assessment sheet on which they are asked to indicate what was good about the presentation, and to give their advice on how it might be improved. Responses are permitted in either English or Japanese. Students are also asked to provide a numerical rating on a scale from one to five, with one being the lowest. Alternatively, they enter their feedback into the university’s Moodle system, and the anonymous responses are gathered in an Excel file and sent by email to each student. The students are also asked to assess their own performances.

For example, in response to a presentation of a story entitled Land and Sea – Kaguya Hime and Mermaid, some students offered the following words of praise in English:

- The illustrations are cute. There are similarities between the two stories, so I thought they made good use of them.

- I’m glad the story had a happy ending. I didn’t know about Mermaid, but I enjoyed it.

- I think it was good that all of you move a lot to act so I can understand the story easily.

Judging by these comments, the students who presented this story were able to combine the Japanese fairy tale about a princess who comes from another world with Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid in an enjoyable manner. More importantly, the students were able to follow and understand the story. Apparently, at least one student was unfamiliar with the latter story, and learned more about it. The actions and illustrations helped their peers to understand the story better, thus emphasizing the importance of visual materials.

They also offered some critical comments:

- A little memorization is in order. I think they have to speak more big voice.

- If character’s faces change depending on the situation, it will be much better.

- More movements will make this play better.

- There was no change in the way they spoke.

While students may not ever again be expected to present a story in class, these comments encouraging memorization, expressions, body movements or gestures, and tone could be applied to future oral presentations and to teachers’ classroom behaviour. They may also be required to develop presentations in which they must share a narrative at conferences or meetings once they finish their education and begin working.

Self-assessment

Finally, these are some of the students’ self-assessments reflecting positive experiences:

- I enjoyed drawing pictures and thinking about stories. When thinking about the story, I was able to successfully combine the story of Issunboushi and the Little Mermaid, so I’m glad.

- The illustrations were hand-drawn and coloured to give the picture-story show a familiar feel. The combination of Japanese and foreign folktales, which everyone knows, made the story easier to understand and more interesting.

- We could use easy English in this puppet show.

- I was able to draw pictures of characters. (Especially a grandma’s picture was best) And l could know a story in Thailand.

- We thought of a miracle collaboration between Little Red Riding Hood and Anpanman. I tried to speak slowly.

- I was able to continue talking smoothly.

From these comments, students seem to have derived satisfaction from coming up with ideas, speaking in English, and illustrating the stories, enhancing their higher order skills. Furthermore, many students were able to critically assess their own performances and determine areas in which they could improve:

- I want to combine other stories or use visuals to tell a story.

- The world view was so different that it became a simple story, so I would like to create an elaborate story by mixing works with works with similar world view.

- There was a lot of narration, so more dialogue would make it more interesting.

- I want to be able to speak English without looking at the paper.

- If we had prepared more, we could do it more smoothly.

- The story was too simple. It could have been a little more interesting.

Students have expressed their enjoyment of this activity in end-of-the semester class surveys. Some have written that they intend to implement mash-up story presentations in their teaching practice.

Conclusion

Although students had little previous experience in creating stories, and some students had limited ability in English, through translanguaging and scaffolding the groups were able to create cohesive, entertaining narratives. Post-activity feedback revealed that they were challenged by creating mash-up stories, and were engaged in watching the presentations by their peers. As they were often at least somewhat familiar with the original stories, both Japanese and non-Japanese, they were able to easily follow the stories as they unfolded, and expressed curiosity and surprise at the variations in the mash-up versions. The activity gave them the opportunity to use English, while developing critical thinking skills and engaging their creativity. Finally, they were able to exercise and develop storytelling skills which will likely be useful in future endeavours, as well as in daily life.

Bibliography

Coburn, Jewell Reinhart, illus. Eddie Flotte. (1998). Angkat: The Cambodian Cinderella. Shen’s Books.

Cullen, Lisa Ann (2018). Little Orange Honey Hood: A Carolina Folktale. The University of South Carolina Press.

Milne, A. A., illus. Ernest H. Shepard. (1926). Winnie-the-Pooh. E. P. Dutton & Co.

Schwartz, Corey Rosen, illus. Dan Santat. (2012). The Three Ninja Pigs. G. P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers.

References

Adams, R., Allendoerfer, C., Smith, T. R., Socha, D., Williams, D., & Yasuhara, K. (2007, June). Storytelling in engineering education [Conference presentation]. 2007 American Society for Engineering Education Conference, Honolulu, HI, United States. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2–2904

Barker, R. T., & Gower, K. (2010). Strategic application of storytelling in organizations: Toward effective communication in a diverse world. The Journal of Business Communication, 47(3), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943610369782

Bland, J. (2018) Playscript and screenplay: Creativity with J. K. Rowling’s wizarding world. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in language education: Challenging reading for 8–18 year olds (pp. 41-61). Bloomsbury Academic.

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review, 2, 1–28.

Charon, R. (2005) Narrative medicine: Attention, representation, affiliation. Narrative, 13(3), 261–270.

Chavez, F. R. (2021). The anti-racist writing workshop: How to decolonize the creative classroom. Haymarket Books.

Debnam, M. (2023). Story structure – What pupils can learn from fairytales. Teachwire. https://www.teachwire.net/news/story-structure-fairytales/

Denning, S. (2006). Effective storytelling: Strategic business narrative techniques. Strategy & Leadership, 34(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570610637885

Garcia, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley & Blackwell.

Garcia, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave McMillan.

Hemley, R., Xi, X. (2021). The art and craft of Asian stories: A writer’s guide and anthology. Bloomsbury Academic

Hornberger, N. H., & Link, H. (2012). Translanguaging and transnational literacies in multilingual classrooms: A biliteracy lens. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15, 261–278.

Kairyudo. (2020). Sunshine English Course 2. Kairyudo.

Kiernan, P. (2005). Storytelling with low-level learners: Developing narrative tasks. In C. Edwards, & J. Willis (Eds.), Teachers exploring tasks in English language teaching (pp. 58–68). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230522961_6

Lloyd, P. (2000). Storytelling and the development of discourse in the engineering design process. Design Studies, 21(4), 357–373.

Massaro, T. M. (1989). Empathy, legal storytelling, and the rule of law: New words, old wounds? Michigan Law Review, 87(8), 2099–2197.

MEXT (2011a). Five proposals and specific measures for developing proficiency in English for international communication. Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. https://www.mext.go.jp/component/english/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2012/07/09/1319707_1.pdf

MEXT (2011b). The revisions of the courses of study for elementary and secondary schools. Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/education/elsec/title02/detail02/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2011/03/28/1303755_001.pdf

MEXT (2017). The second basic plan for the promotion of education. Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/education/lawandplan/title01/detail01/1373796.htm

Monarth, H. (2014, March 11). The irresistible power of storytelling as a strategic business tool. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/03/the-irresistible-power-of-storytelling-as-a-strategic-business-tool

Ofri, D. (2005). The passion and the peril: Storytelling in medicine. Academic Medicine, 90(8), 1005–1006. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000672

Pacheco, M. B., & Miller, M. E. (2015). Making meaning through translanguaging in the literacy classroom. The Reading Teacher, 69(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1390

Rideout, C. (2008). Storytelling, narrative rationality, and legal persuasion. The Journal of the Legal Writing Institute, 14, 53–86.

Rozakis, L. E. (2004). The complete idiot’s guide to creative writing (2nd ed.). Alpha Books.

Salesses, M. (2021). Craft in the real world: Rethinking fiction writing and workshops. Catapult.

Shuman, A. (2005). Other people’s stories: Entitlement claims and the critique of empathy. University of Illinois Press.

Terauchi, H. (2017). English education at universities in Japan: An overview and some current trends. In E. S. Park, & B. Spolsky (Eds.), English education at the tertiary level in Asia: From policy to practice (pp. 65–83). Routledge.

Thompson, H. (2021). Creative portfolios: Adapting AWP goals for EFL creative writing courses in Japan. In M. Moore, & S. Meekings (Eds.), The place and the writer: International intersections of teacher lore and creative writing pedagogy (pp.107–128). Bloomsbury Academic.

Turnbull, B. (2018). Is there a potential for a translanguaging approach to English education in Japan? Perspectives of tertiary learners and teachers. JALT Journal, 40(2), 101–134.

Yamauchi, D. (2018). Translanguaging in the Japanese tertiary context: Student perceptions and pedagogical implications. Niigata International University of Information Sciences Center Bulletin, 3, 15–27. https://cc.nuis.ac.jp/library/files/kiyou/in2018/in2018_002.pdf

Appendix 1. Mash-up of Little Red Riding Hood and Momotaro

One day, Little Red Riding Hood went to her grandmother’s house. Her grandmother’s house is deep in the mountains. When she got to her grandmother’s house, her grandmother [was] being eaten by a wolf. The wolf immediately ran into the mountains. She felt powerless because she couldn’t do anything for her grandmother. She remembered happy memories with her grandmother and she wept. So, she went to kill the wolf.

Next day, she visited Momotaro because she heard that Momotaro [had] defeated the demon. She wanted to get as much power as Momotaro. So, she became Momotaro’s apprentice. She trained under the guidance of Momotaro. She trained for three years. First, she fought Momotaro’s servants – dogs, monkeys, and pheasants. She vowed revenge on the wolf who ate [had eaten] her grandmother. Then she went to the wolf and [to] fight.

The Red girl succeeded in halving the strength of the enemy wolf, but the wolf evolved. Grandmother and the wolf united into a second form. The Red girl hesitated to kill the wolf because she could sense her grandmother’s presence.

The Red girl was able to kill the wolf after a desperate struggle.

Momotaro’s mysterious power brought her grandmother back to life. She and her grandmother were able to meet again.

Happy end.

The shadow of the wolf moved….

To be continued.

Appendix 2. Mash-up of Bam and Kero and the Philosopher’s Stone

Today is Friday. Bam found a book of magic in the attic which is Bam’s father’s and mother’s. Kai-chan, he is a duck, flies in the window. The letter is tied to his leg. The letter is an invitation from Hogwarts. Bam and Kero enter Hogwarts. They enter Hufflepuff by the sorting hat. They are having a good time in Hogwarts.

One day, they see that a teacher talks [is talking] with a suspicious person. They know that the teacher wants to steal the Philosopher’s stone.

Bam presented handmade donuts to Cerberus and they became good friends. They can protect the Philosopher’s stone.

Hufflepuff received an award for the courageous action.

When they wake, they are in the house.