| Developing Student Teachers’ Sustainability Competence through Picturebooks

Malin Lidström Brock |

Download PDF |

Abstract

To effectively utilize picturebooks as teaching resources for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in the English language classroom, teachers must possess a set of interrelated competencies. Among these is the ability to analyse and evaluate the content of picturebooks to determine their suitability for ESD in English Language Teaching (ELT). This study presents a literature module that aimed to develop the ability of student teachers for the grade levels 1 to 3 (children in the age range seven to nine in Sweden) to combine ESD with ELT using picturebooks. The activities in the module were designed to achieve a progression from simple and concrete to complex and abstract forms of learning. The study outlines the module’s practical application in a teacher education English course at a Swedish university and evaluates the outcome by assessing lists of criteria that the student teachers created to help them determine the suitability of picturebooks in English for ESD.

Keywords: early childhood education, English language teaching, sustainability, teacher education, young learners

Malin Lidström Brock is Senior Lecturer in English and Education at Luleå University of Technology. She is currently coordinator of the Primary Education Programmes for grades 1-3 and 4-6. Her research interests include contemporary literature and culture, more recently with a focus on sustainability and gender.

Introduction

The role of English as a global lingua franca suggests that ELT can play a central part in introducing learners to sustainable ways of living and acting. The implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is challenging for primary school teachers, however, since young learners are taking their first steps towards acquiring a second language and they are on a cognitive level that is likely to differ from intermediate and advanced learners (Alter, 2022). Picturebooks promise a solution to this dilemma by providing primary school teachers a means by which to introduce sustainability issues to young learners of English (Bland, 2014; Hsiao & Shi, 2015; Ibrahim, 2020; Yeh & Li, 2022).

The national steering documents for English in Swedish primary school for grade levels 1 to 6 do not specify literature as part of the subject’s core content (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2022), yet literature modules are typically included in English courses for student teachers at Swedish universities. In syllabi for English courses in teacher education for grade levels 1 to 3, literature is defined primarily as an instrument for language learning (Dodou, 2021). The literature module presented in this study is based on the belief that teachers can benefit from harnessing the opportunities of picturebooks also for teaching ESD. The intended outcome of the module presented in this study is a student teacher of grades 1 to 3 who feels confident in choosing literary material suitable for both ELT and ESD.

Approaching Picturebooks

Picturebooks have received considerable attention from literary scholars and educators, who recognize their value as multimodal forms of literature, as well as effective educational tools (Bland, 2018). The picturebook is a formally complex genre that relies on both visual and verbal means of communication (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2018; Nikolajeva & Scott, 2002; Nodelman, 1988). Indeed, Narančić Kovač (2018) observes that ‘the relationship between pictures and words is a topos of picturebook research’ (p. 411). As such, the format can ‘perplex teachers and children alike’ (Bland, 2013, p. 36) and seems to demand an advanced reader, who can identify the full potential of using picturebooks in the classroom (Narančić Kovač, 2016).

In a linguistic analysis of picturebooks, the verbal and the visual aspects of the format should ideally be understood as integral (Gressnich, 2018). In several ELT tertiary textbooks, however, the images in picturebooks are regarded primarily as non-linguistic scaffolds, which serve to improve reading comprehension or act as models for written and oral responses from young learners (see, for example, Keaveney & Lundberg, 2023; Lundberg, 2020; Lado, 2012). In comparison, a content analysis that seeks to identify how individual picturebooks address certain topics must consider both the verbal and the visual properties of a book when trying to understand how its specific characters, setting and plot contribute to the main theme. From a reader-oriented perspective, words and pictures can be understood spatially, or holistically, as well as sequentially (Narančić Kovač, 2018; Nodelman, 1988). Both elements carry meaning informed by style, subject and mood, but they might not convey the same message (Nodelman, 1988). Words and pictures can exist in ‘counterpoint,’ which means that the two properties communicate alternative information (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006, p. 17). They can also complement each other or exist in a relationship of symmetry (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006).

Picturebooks and ESD

In the 1990s, the UN put forth the need for sustainable development, defined in the Brundtland Report as a ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (United Nations, 1987). The 17 sustainable development goals that have been created since then make up a set of interlinked, action-based objectives that function as a ‘plan of action for people, planet and prosperity’ (United Nations, 2017). The implementation of the goals has become worldwide. In 2022, the Council of the European Union proposed that all educators become sustainability educators, no matter their discipline or sector of education.

Educators and researchers have established that picturebooks can be used successfully to teach environmental consciousness, address social justice issues and promote intercultural and transcultural awareness in ELT and in early childhood education in general (see, for example, Alter, 2018; Bland, 2014; Hsiao & Shih, 2015; Spearman & Eckhoff, 2012). The cultural influence of picturebooks on young learner can, in other words, be substantial if handled with competence and purpose. The literature module outlined in this study follows the advice of, among others, Bland (2014), who argues for the inclusion of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in ELT, as a vital and enriching complement to the communicative aspects of language learning emphasized in the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2024).

ESD involves taking an ideological approach to literature. The action-based nature of ESD requires that the question of what literature studies in ELT are for, beyond the communicative skills that they are meant to develop, must be addressed. From a global perspective, young learners have little actual agency and power over their own lives. As such, they have limited ability to ‘actively and critically participate in and contribute to their local and global communities’ (Alter, 2022, p. 59). The question of purpose has been brought up in relation to the ecocritical dimensions of ESD (see Bartosch & Garrard, 2013; Major & McMurry, 2012). For Bartosch and Garrard (2013), the answer to the question of purpose is that the study of literature from an ecocritical, and therefore also from a sustainability, perspective makes possible ‘the right sorts of questions’ and encourages learners in ‘their own search for answers’ (p. 7). If one considers the priority with which environmental concerns and climate change hold vis-à-vis social justice topics, such as class, gender and race (Bland, 2014), it is also worth turning to Bhagwanji and Born (2018) for a partial answer to what literature can do for young learners in an ESD context. To Bhagwanji and Born (2018), ‘environmental literacy,’ ‘joy brought on by a closeness to nature’ and, not least, a ‘sense of wonder, appreciation for beauty and mystery of the natural world,’ they argue, are some of the positive effects of thoughtfully selected children’s literature, including picturebooks, on young learners (p. 87).

Module Design and Theoretical Framework

The literature module presented in this study takes as its starting point a content analysis of a selection of picturebooks. The activities in the module were designed to correspond with a revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy of objective outcomes (Bloom et al., 1956; revised by Krathwohl, 2002). The taxonomy categorizes and classifies the cognitive domain of learning at distinct levels according to complexity and abstraction. More specifically, the different levels in the taxonomy signify a progression from simple to complex, and concrete to abstract, forms of learning. In the module presented in this study, the outcomes of the first activity aimed to correspond with the levels knowledge and comprehension in the original taxonomy, which in the revised version has been translated into verbs, such as identifying or recognizing, and classifying and explaining, respectively. The second activity progressed to application, which in the revised taxonomy is expressed through the verbs carrying out or using. The third activity intended to move the students further up the taxonomy, to the levels of analysis and synthesis, or categorizing and evaluating, while the intended outcome of the fourth activity was creation, translated into the verbs combining, choosing, and developing.

The module integrated Bloom’s taxonomy with the social constructivist theories of Vygotsky (1978). All the activities in the module were conducted in small groups, based on the assumption that intellectual growth is enhanced and accelerated through social interaction. The module was structured on the principle that the members in each group would progressively reach new heights of understanding and skill, or learning outcomes in Bloom’s taxonomy, by assisting each other. Every activity sought to hone the student teachers’ ability to assess and evaluate, even when these abilities were not primary aims.

The sections that follow outline the activities that made up the module and provide a short account of the results of each activity. Every activity was begun and completed during a 90-minute seminar, with the exception of activities four and five, which were completed outside the seminars. The first two seminars focused on three picturebooks: Dear Earth (Otter & Anganuzzi, 2021), Tree Full of Wonder (Smithers & Nejman, 2021) and Tidy (Gravett, 2016). The selection of the picturebooks was thematic, but also a choice based on convenience, since the books are in print and were therefore available to all participants. For the third activity in the module, the student teachers were given access to a broader selection of picturebooks that touch on sustainability topics such as social justice and global citizenship. Collectively, then, all picturebooks deal with topics that can be linked to at least one of the three major aspects of sustainable development (environment, society, economy) and have potential as material suitable for ESD. For a complete list of the picturebooks, see the Appendix. The fourth activity asked the student teachers to create a list of selection criteria to help them choose picturebooks suitable for both ELT and ESD, while the final activity was a written reflection, which was completed individually.

The Participants in the Study

This study relies on assignments completed by a class of student teachers at a Swedish university. The participants were already familiar with ESD as a concept, which they had been introduced to in a natural science course in their teacher training programme. They also possessed some knowledge of the UN’s 17 sustainability goals before they began the module (United Nations, 2015). At the beginning of the module, many of the participants expressed enthusiasm for using picturebooks in ELT but were doubtful whether such use could be combined with ESD.

Activity One: A Content Analysis

The first activity in the module asked the student teachers to perform a basic content analysis of the three pre-selected picturebooks, Dear Earth (2021), A Tree Full of Wonder (2021) and Tidy (2016), from an ESD perspective. The aim of the activity was to identify how nature is represented in each book and how characters, setting and plot contribute to that representation. The study does not leave room for a comprehensive presentation of the analyses performed by the student teachers who partook in the module. A short summary will therefore have to suffice.

In Dear Earth, a young girl writes a letter to Earth, in which she envisions herself exploring different parts of the natural world. Several participants in the module highlighted the scarcity of plot development in the picturebook. Each double-page spread in the book portrays a different natural environment, such as the ocean or the steppe, and the animals that typically habitat each setting. The student teachers noticed that the girl character appears in every image, but they did not identify the correspondence between her visual presence and the first-person voice in her letter until this was pointed out to them, nor did they perceive the anthropocentric perspective of the girl’s constant presence or her explorative aspirations as problematic from a sustainability point of view. Instead, they observed that the girl’s diminutive appearance in the images highlighted the magnificence of the natural environment, which they interpreted as one of the book’s main messages. Most student teachers stated that they would include Dear Earth in their ELT if it could encourage young learners to pay attention to the beauty and the wonders of the natural world.

In contrast, none of the groups liked Tree Full of Wonder, which lacks a plot and is best described as an informational picturebook (Merveldt, 2018). Apart from the final pages, each double-page spread in the book describes how trees contribute to the protection of the environment and the aesthetic, historical and existential role that they play in the lives of humans. Merveldt (2018) argues that successful informational picturebooks need to draw on culturally specific narrative and descriptive forms to engage readers intellectually and emotionally. The student teachers found the organization of the verbal information presented in Tree Full of Wonder confusing and no one could identify any visual links between the spreads apart from the recurrence of trees and various child characters. All groups identified the message of the picturebook as tree conservation through the planting of new trees and the conservative use of paper. Lack of time stopped the class from considering the effects of such actions in a real-world context.

When Tidy was analysed none of the participants found the anthropomorphized animals in the picturebook problematic. A possible explanation for this might be the prevalence of personified animals in picturebooks (Hooykhaas et al., 2022). The plot in Tidy follows a classic structure, where the rising action results in a climactic moment that changes the trajectory of events. Pete, the badger, decides to tidy up his immediate environment but ends up destroying it instead. Once he realizes that his actions have made him homeless, he sets out to recreate the environment that his cleaning up has demolished. Several groups observed an ironic distance between the visual and the verbal properties of the picturebook. While Pete is the text’s sole focalizer, the images include additional animals, whose facial expressions reveal anxiety when observing the badger’s actions. All groups found the plot amusing, but some were uncertain about the book’s message, since the book does not provide a more environmentally friendly alternative to Pete’s destructive cleaning up. As a result, they worried that young learners, too, would find the picturebook confusing. None of the student teachers commented on the fact that the pictures present a park landscape rather than a forest, even though a forest is referred to as the setting in the verbal text. Consequently, they did not consider why an environment created entirely by humans is described ‘as it always has been’ (Gravett, 2016) after Peter has restored the landscape to its earlier condition, nor what ecological message this comment might send to young readers.

Several student teachers recognized that the language and grammar in the picturebooks might be too advanced for very young learners of English. That ESD through picturebooks in English has to take place through the medium of Swedish because of the young learners’ limited English knowledge, was not seen as a problem by the participants in the module. However, since the hours assigned to teaching English in Swedish primary school for ages seven to nine are few (a total of 60 hours divided over the course of three years) compared to the hours assigned to Swedish (680 hours divided over three years), introducing a topic through a picturebook in English and then conducting the discussion in Swedish was seen as a productive way to combine the two subjects.

Activity Two: A Digital Picturebook

In the second seminar, the student teachers were tasked with considering the topics introduced in seminar one through an aesthetic form of expression. The groups had to create their own picturebooks in the programme Storyjumper. For this assignment, the student teachers were supposed to apply the knowledge that they had presumably acquired during the content analysis in seminar one to a particular and concrete situation. The assignment instructions stated that the digital picturebook should be suitable for ELT in grades 1 to 3 and address a sustainability-related topic or goal. Participants could base their picturebook on Dear Earth, Tree Full of Wonder or Tidy by creating a sequel or parallel story, but this was not a requirement. The programme Storyjumper was chosen for two reasons. It was free of charge and relatively easy to use also for a complete beginner.

The activity resulted in thirteen picturebooks. Of these, six picturebooks took their inspiration from the picturebook Tidy, four from Dear Earth, and two from Tree of Wonder. One picturebook was not based on any of the three picturebooks from seminar one. Of the thirteen student-created picturebooks, most included writing at a language level that was suitable for children in grades 1 to 3. Minor language mistakes in the picturebooks reflected variations in the participants’ English proficiency. The collaborative nature of the assignment meant that these mistakes could not be linked to individual student teachers’ contributions, and they were not brought up when the picturebooks were presented in class.

All the picturebooks touched upon the topic of sustainability in their content. Together, the thirteen picturebooks linked to a total of five identifiable sustainability goals. These were goal 6: clean water and sanitation; goal 8: decent work and economic growth; goal 13: climate action; goal 14: life below water and goal 15: life on land. Of these goals, 13, 14 and 15 had previously been identified by the students as addressed in the three picturebooks assigned to the first part of the module, while goals 6 and 8 had not been brought up in previous discussions.

Extracts from two student-created picturebooks serve to illustrate what lessons, if any, the student teachers had drawn from the content analyses performed in seminar one, and whether they could articulate the content of these lessons when they created their own picturebooks. In the student-made picturebook Letter from Earth, anthropomorphized animals are introduced on one page of every spread. The animals speak in simple sentences and use set phrases, while the words on the opposite pages come from a letter written by Earth and address environmental concerns (see Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Pages 3-4 from Letter from Earth (based on Dear Earth).

Figure 2: Pages 19-20 from Letter from Earth (based on Dear Earth).

Figure 3: Pages 21-22 from Letter from Earth (based on Dear Earth).

Of particular interest are the anthropomorphized animals in Letter from Earth. Storyjumper allows for the inclusion of pictures that users can upload from anywhere. In the picturebook, the student teachers depart from the anthropocentric perspective of Dear Earth. Instead, they introduce ‘cute,’ anthropomorphized animals as main characters and the Earth as narrator. The anthropomorphizing of the animals in the picturebook is occasionally challenged by the letters from Earth, such as the warning to readers against real wolves (Figure 3). Such a warning, however, is missing when a polar bear (Figure 1) is introduced earlier in the picturebook.

The anthropomorphizing of animal characters is a contested topic. Some researchers argue that ‘cute’ visual portrayals of animals, such as polar bears and wolves with human-like features (Figures 1 and 2), can affect children’s knowledge of animals negatively (Ganea et al., 2014; Marriott, 2002). Others contend that anthropomorphically portrayed animals make them relatable for children (Chan, 2012), which can aid in their learning about the natural world (Geerdts et al., 2016). The extent to which the appearance of ‘cute’ animals makes young readers care more about the threats to animals and their habitats, is therefore up for debate and should ideally be brought up as a topic for discussion in future iterations of the course, especially since many award-winning creators of picturebooks seek to avoid cuteness in their portrayal of animals.

The student-made picturebook Can I Get a Break? serves as an example of how a loose adaptation of Tidy allowed another group of student teachers to bring up a topic that departs from the environmental content of the three picturebooks which they had studied so far. Can I Get a Break? communicates the need for decent work conditions through a revision of the content of the original book. Workers’ rights form part of sustainability goal 8, yet it is a topic that is not addressed in Tidy.

Figure 4. Pages 9-10 from Can I Get a Break? (based on Tidy).

Figure 5. Pages 13-14 from Can I Get a Break? (based on Tidy).

In Can I Get a Break?, Pete is a badger who puts the other animals to work in cleaning up the forest and does not allow them any rest (Figure 4). It is only when the other animals protest that Pete realizes that he has created unfair working conditions for them, and he subsequently changes these conditions for the better. As a result, everyone is happy, including Pete, who realizes that his ambition to clean up the forest had gone too far (Figure 5).

The landscape in the picturebook resembles the environment in Tidy, yet in the student-produced picturebook the park-like milieu matters less, since the theme in Can I Get a Break? appears to differ from the main theme of Tidy, although none of the participants in the course was sure what message the latter sought to communicate. The content of Can I Get a Break? reveals a basic awareness of the kind of content a picturebook needs to make it suitable for ESD. Equally important, the picturebook demonstrates that the student teachers who created it recognize that ESD include topics beyond purely environmental concerns.

Activity Three: A Thematic Assessment

The third group activity aimed to develop the student teachers’ ability to critically assess and select picturebooks suitable for ESD in ELT. In the process, it also sought to hone their metacognitive skills, such as the ability to select, implement and critically assess their use of classroom material and accompanying activities. To achieve these aims, the groups were asked to rely on a pre-made assessment guide in the form of a grid (see Tables 1 to 4), loosely based on the four ‘knowledge processes’ established by New London Group (1996) and Kalantzis and Cope (2016), and further developed by Reyes-Torres and Portalés Raga (2020). Here, the grid has been revised and divided into four tables for the sake of clarity.

In activity three, the student teachers were assigned picturebooks on topics that could be connected to sustainability goals promoting global citizenship and social justice, such as goal 1: no poverty, goal 5: gender equality, goal 10: reduced inequalities and goal 16: peace, justice and strong institutions. A complete list of the picturebooks used in the activity can be found in the Appendix. Each group was randomly assigned two picturebooks from the list.

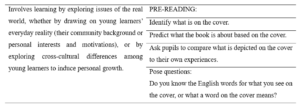

Table 1. Experience

The first step of the activity (Table 1) asked the student teachers to analyse the covers of the two picturebooks to determine whether the books seemed to explore real-world issues and sustainability goals related to social justice or global citizenship. To help them in this task, the grid also included questions that might be brought up in the primary school classroom when teachers introduce a picturebook.

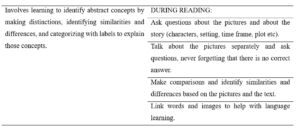

Table 2. Conceptualize

The second part of the grid (Table 2) asked the participants to consider picturebooks as value-laden literature that rely on abstract concepts which can be identified, categorized and then analysed. To determine whether the picturebooks were suitable material for helping young learners develop sustainability awareness, first the groups had to identify which abstract concepts could be found in the content and then determine how to categorize these concepts.

At this stage, the ideological aspects of using literature in ESD became obvious. The activity resulted in sometimes heated discussions in the groups about which categories and topics were appropriate to approach in primary school for the purpose of ESD. Some of students believed that skin colour should never be discussed, while others argued that a picturebook such as Sulwe (Nyong’o & Harrison, 2021), which addresses the topic of skin colour, should be part of every classroom. Other groups argued for the inclusion of the picturebook The Kindest Red: A Story of Hijab and Friendship (Muhammad et al., 2023) to promote diversity, while others criticized the picturebook for seemingly normalizing hijabs on young girls.

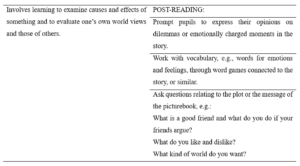

Table 3. Analyse

Attempts to conceptualize the kinds of values that seemed to inform the picturebooks also resulted in the discussions about what kinds of activities could take place after reading (Table 3). This part of the activity required the groups to imagine how they might practically apply the categories and labels that they had identified in the earlier part of the seminar (Table 2). Once again, the grid included example activities and questions for the primary school classroom to help the student teachers assess the picturebooks’ suitability for ELT and ESD.

Table 4. Apply

The final part of the grid required that the participants explore how they could work with the themes brought up in the picturebooks in ways that did not involve the picturebook itself. This part of the activity demanded that the student teachers had read and analysed the content of the picturebooks, but also considered how classroom activities could be applied to help young learners advance their English language skills and sustainability awareness (Table 4).

In activity three, the participants in the module assessed their assigned picturebooks with the help of an assessment guide in the form of a grid that described four knowledge processes of learning (experience, conceptualize, analyse and apply), while also developing their own meta-cognition. The purpose of the grid was to prepare the students for activity four, where the groups collectively had to decide upon a list of criteria that might help them to determine whether to introduce a certain picturebook into the ELT classroom.

Activity Four: Choosing Picturebooks Suitable for ESD in ELT

The final group activity in the module asked the participants to create a list of criteria for choosing picturebooks suitable for ESD in ELT. Previous studies suggest that English language teachers lack confidence in choosing picturebooks suitable for ESD (Spearman & Eckhoff, 2012; Yeh & Li, 2022). A set list of criteria could therefore help teachers to choose which picturebooks to include in the ELT classroom for teaching sustainable development (Yeh & Li, 2022). In this activity, the aim was to create a list of criteria. The students should also explain why these criteria were included on the list and apply the criteria on three picturebooks of their choice from the module. Although the groups were free to come up with their own criteria, they were given a list of 39 possible criteria amassed from previous studies (Bhagwanji and Born, 2018; Bland, 2014; Buell, 1995; Derman-Sparks, 2023; Yeh & Li, 2022). Some of these criteria were revised for clarity and brevity before they were sent to the groups at the start of the activity.

After the deadline, twelve groups had submitted lists. The twelve lists included a total of 48 selection criteria. All 39 criteria from the pre-made list could be found on the groups’ lists, but more than half of these occurred on a single list, which was an outlier list consisting of fully 32 criteria. The other groups’ lists included between four and thirteen criteria each. Listed below are the twelve criteria which were included on at least four lists. All the criteria on the compiled list below came from the pre-made list. The number following each criterion state the number of group lists on which that particular criterion appeared:

- The pictures are captivating and hold children’s interest. (8)

- The story and pictures trigger self-reflection and thinking. (8)

- Solidarity and empathy with others are dominant themes in the story. (7)

- Vocabulary and pictures promote diversity and inclusion. (5)

- At least one of the three major aspects of sustainable development (environment, society, economy) is in focus. (5)

- Stereotypes about particular identity markers (for example, gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, disability) and minoritized groups, whether in human or non-human form, are not included. (4)

- Groups and individuals that are often absent from picturebooks (for example, families that practice Islam, low-income families, transgender adults and children) are included. (4)

- Human accountability to and responsibility for the environment is part of the text’s ethical orientation. (4)

- The pictures demonstrate a sense of wonder towards the beauty of nature. (4)

- The story promotes verbal and visual literacy through the inclusion of words and images relating to the natural world. (4)

- Child characters are presented as individuals who can think critically and logically. (4)

- The story is engaging and hopeful. (4)

Criteria 1, 2 and 4 recognize that picturebooks consist of both verbal and visual signs. These criteria might appear high on the list because of the content analysis that the participants performed in seminar one, or simply because the combination of words and pictures is a key feature of the picturebook format itself. That the student teachers acknowledged the importance of pictures in children’s enjoyment of picturebooks is suggested by the inclusion of criterion 1 on the list, while criterion 9 specifies what might contribute to such an enjoyment. Criteria linked to social justice, such as the need for diversity and inclusion in picturebooks, appear on at least seven lists through criterion 3. Other criteria on the compiled list that emphasize social justice are criterion 7, which articulates what diversity and inclusion can look like in picturebooks, and criterion 6, which warns against picturebooks that promote stereotypes.

Criteria from the pre-made list that underline environmental and climate concerns also made it onto the compiled list. Criteria 8, 9 and 10 relate directly or indirectly to connections between human beings and their natural environment. Relatively few criteria relating to the environment made it onto the compiled list when one considers that the picturebooks on which most of the groups chose to apply their criteria were Tidy and Dear Earth, two picturebooks that supposedly address the need for environmental conservation and care. Because these picturebooks were obligatory reading material in the module, the decision to apply the criteria on these books might have been made for practical reasons; every participant in the module was sure to have access to the two picturebooks. The third obligatory picturebook, Tree Full of Wonder, was assessed by a single group. That social justice topics appeared as often as environmental topics might have been an effect of the proximity of activity three to activity four, when the groups were asked to create their lists. During activity three some of the participants read and assessed picturebooks with social justice themes.

Finally, certain criteria on the list indicate that the student teachers took their future young learners into account when they came up with their lists. Criterion 11 requires picturebooks about child characters who can think critically and logically, while criterion 2 asks for picturebooks that will trigger similar (critical) thinking skills and self-reflection in their readers. Together with criteria 8 and criteria 12, which ask for picturebooks that can visually stimulate readers’ imagination, and engage and give them hope, these four criteria suggest that the student teachers were optimistic about the extent to which literature in ESD can contribute to raising learners’ consciousness of the need for a sustainable future. None of the goals, however, required a picturebook which demanded that readers take action to ensure such a future.

Concluding Thoughts

The purpose of this study was to present an outline for, and assess the outcome of, a small literature module which sought to combine ESD with ELT and was aimed at future teachers of young learners. A strong motivator for the creation of the module was a belief that CLIL can enrich the communicative aspects of ELT. Another motivating factor is the notion that the very survival of our societies and the planet depends on sustainable ways of living. The module, which has been implemented only once at the time of writing this paper, was an attempt to answer the call from the Council of the European Union on the need for educators of all kinds to promote sustainability. The hope was that the module’s dependence on Bloom’s taxonomy for its design would lead the participating student teachers to feel confident in choosing literary material suitable for both ELT and ESD in primary school.

To achieve this aim, the module guided its participants through four related activities that were designed to build on each other. Of these activities, the second asked the student teachers to create a digital picturebook. The finished products suggest that a single seminar during which the students were introduced to and analysed the content of three picturebooks was not sufficient preparation for making their own picturebooks. Despite this realization, most students still named the second activity as their favourite in their reflections. As an exercise in practically trying to figure out what kind of content a picturebook needs to have to be considered for ESD in ELT, it might still have its uses.

In future versions of the module, the student teachers’ assessment of picturebooks as material specifically suitable for ELT will also require more support, ideally through reading material that provides them with linguistically precise terminology (Gressnich, 2018). Any such material must nevertheless be complemented by information about the social meaning of picturebooks, which is created when picturebooks are read aloud and change depending on participants and situations (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2002).

If activity two illustrated the illusory simplicity of picturebooks, the content analyses that took place in the module revealed that sustainability is a concept that requires thoughtful consideration also by authors and illustrators of picturebooks. The picturebooks selected for the module were not meant to be exemplary, but examples of picturebooks that in one way or another made claims to promote sustainability. In future iterations of the module Tidy might benefit from a comparison with, for example, Fox: A Circle of Life Story (Thomas & Egnéus, 2020), which portrays the ecological processes involved in the decomposition of a fox corpse in a forest, the very processes that Pete’s tidying destroys. The module might also benefit from the replacement of Tree Full of Wonder with another picturebook, such as The Oak Tree (Donaldson & Sandøy, 2023), in which readers are introduced to the life of an oak, from acorn to toppled trunk, over a 1,000-year period. Such a time span is difficult to comprehend even for adults yet is made understandable to young readers through the picturebook.

As pointed out by Alter (2022), young learners have little actual agency when it comes to having a meaningful influence over their environment. It is questionable whether the actions that young learners are typically asked to perform in the name of sustainable development will have any significant impact on their or other people’s lives. Dear Earth and Tree Full of Wonder include child characters and list actions that young readers can supposedly take to help preserve and improve the local and the global environment, such as recycling trash and conserving water. The presence of child characters and lists of eco-friendly activities suggest that the onus lies on children to improve environments, economies and societies in a meaningful way. Whether these expectations are realistic or fair, only the future can tell.

Bibliography

Donaldson, Julia, illus. Victoria Sandøy (2023). The Oak Tree. Alison Green Books.

Gravett, Emily (2016) Tidy. Two Hoots.

Muhammad, Ibtihaj, & S. K. Ali, illus. Hatem Aly (2023). The Kindest Red: A Story of Hijab and Friendship. Andersen Press.

Nyong’o, Lupita, illus. Vashti Harrison (2021). Sulwe. Puffin.

Otter, Isabel, illus. Clara Anganuzzi (2021). Dear Earth. Caterpillar Books.

Smithers, Anna, illus. Martyna Nejman (2021). Tree Full of Wonder. Orange Lotus Publishing.

Thomas, Isabel, illus. Daniel Egnéus (2020). Fox: A Circle of Life Story. Bloomsbury Children’s Books.

References

Alter, G. (2022). Picturebook biographies and environmental education in primary English. In R. Bartosch, & C. Heidelberg (Eds.), Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies, Focus on Ecological English Language Teaching (pp. 59-74), Winter.

Alter, G. (2018). Integrating postcolonial culture(s) into primary English language teaching. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 6(1), 22-44.

Bartosch, R., & Garrard, G. (2013). The function of criticism: A response to William Major and Andrew McMurry’s editorial. Journal of Ecocriticism, 5(1), 1-6.

Bhagwanji, Y., & Born, P. (2018). Use of children’s literature to support an emerging curriculum model of education for sustainable development for young learners. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 12(2), 85-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408218785320

Bland, J. (2018). Learning through literature. In S. Garton, & F. Copland (Eds.), Routledge handbook of teaching English to young learners (pp. 269-287). Routledge.

Bland, J. (2014). Ecocritical sensitivity with multimodal texts in the EFL/ESL literature classroom. In R. Bartosch, & S. Grimm (Eds.), Teaching environments: Ecocritical encounters (pp. 75-96). Peter Lang.

Bland, J. (2013). Children’s literature and learner empowerment. Bloomsbury.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Kraftwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. David McKay Company.

Buell, L. (1995). The environmental imagination. Harvard University Press.

Chan, A.Y-H. (2012) Anthropomorphism as a conservation tool. Biodiversity and Conservation, 21(7), 1889–1892.

Council of Europe (2024). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages

Council of the European Union (2022, June 16). Proposal for a council recommendation on learning for environmental sustainability. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022DC0011

Derman-Sparks, L. (2023) Guide for selecting anti-bias children’s books. Social Justice Books: A Teaching for Change Project. https://www.teachingforchange.org/

Dodou, K. (2021). Why study literature in English? A syllabus review of Swedish primary teacher education. Utbildning & Lärande, 15(2), 85-105.

Ganea, P. A., Canfield C. F., Simons-Ghafari K., & Chou, T. (2014). Do cavies talk? The effect of anthropomorphic picture books on children’s knowledge about animals. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00283

Geerdts, M. S., Van de Walle G. A., & LoBue, V. (2016) Learning about real animals from anthropomorphic media. Imagination, Cognition and Personality: Consciousness in Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice, 36(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/027623661561

Gressnich, E. (2018). Picturebooks and linguistics. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 401-408). Routledge.

Hooykhaas, M. J. D., Holierhoek, M. G.,Westerveld, J. S., Schilthuuzen, M., & Smeets, I. (2022). Animal biodiversity and specificity in children’s picture books. Public Understanding of Science, 3(32), 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221089811

Hsiao, C.-Y., &Shih, P.-Y. (2015). The impact of using picturebooks with preschool students in Taiwan on the teaching of environmental concepts. International Education Studies, 8(3), 14-23. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n3p14

Ibrahim, N. (2020). The multilingual picturebook in English language teaching: Linguistic and cultural identity. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 8(2), 12-38.

Kalantzis, M, & Cope, B. (2016). Literacies. Cambridge University Press.

Keaveney, S., & Lundberg, G. (2023). Early language learning and teaching: Pre-A1-A2. Studentlitteratur.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212–218.

Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (Ed.). (2018). The Routledge companion to picturebooks. Routledge.

Lado, A. (2012) Teaching beginner ELL using picture books: Tellability. Cowin Press.

Lundberg, G. (2020). De första årens engelska. Studentlitteratur.

Major, W., & McMurry, A. (2012). Introduction: The function of ecocriticism; or, ecocriticism, what is it good for? Journal of Ecocriticism, 4(2). 1-7.

Marriott, S. (2002). Red in tooth and claw? Images of nature in modern picture books. Children’s Literature in Education, 33(3), 175–183.

Merveldt, N. von (2018). Informational picturebooks. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 231-245). Routledge.

New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92.

Narančić Kovač, S. (2016). Picturebooks in educating teachers of English to young learners. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 4(2), 6-26.

Narančić Kovač, S. (2018). Picturebooks and narratology. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 409-419). Routledge.

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C. (2002). How picturebooks work. Routledge.

Nodelman, P. (1988). Words about pictures: The narrative art of children’s picturebooks. The University of Georgia Press.

Reyes-Torres, A., & Portalés Raga, M. (2020). Multimodal approach to foster the multiliteracies pedagogy in the teaching of EFL through picturebooks: The Snow lion. Atlantis. Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, 42(1), 94–119. https://doi.org/10.28914/Atlantis-2020-42.1.06

Spearman, M., & Eckhoff, A. (2012). Teaching young learners about sustainability. Childhood Education, 88(6), 354-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2012.741476

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2022). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare 2022. Swedish National Agency for Education.

United Nations. (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development: Our common future. Oxford University Press.

United Nations. (2015). The 17 goals. Sustainable development goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

United Nations. (2017). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017. Work of the statistical commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://ggim.un.org/documents/a_res_71_313.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes (pp. 79-91). Harvard University Press.

Yeh, S.-C., & Li, H-Y. (2022). Developing a sustainable development-oriented picture book selection system through employing the modified delphi method. Journal of Baltic Science, 21(6), 967-988. https://doi.org/10.33225/jbse/22.21.967

Appendix: Picturebooks in the Module

Browne, Anthony (2010). Me and You. Doubleday.

Do, Anh, & Suzanne Do, illus. Bruce Whatley (2011). The Little Refugee. Allen & Unwin Children’s Books.

Donaldson, Julia, illus. Victoria Sandøy (2023). The Oak Tree. Alison Green Books.

Glynne, Andy, illus. Salvador Maldonado (2018). Ali’s Story: A Real-Life Account of His Journey from Afghanistan. Picture Window Books.

Glynne, Andy, illus. Salvador Maldonado (2017). Juliane’s Story: A Real-Life Account of Her Journey from Zimbabwe. Picture Window Books.

Glynne, Andy, illus. Salvador Maldonado (2014). Rachel’s Story: A Journey from a Country in Eurasia. Picture Window Books.

Gravett, Emily (2016). Tidy. Two Hoots.

Lord, Michelle, illus. Julia Blattman (2020). The Mess that We Made. Flashlight Press.

Milne, Kate (2019). It’s a No-Money Day. Barrington Stoke.

Muhammad, Ibtihaj, & S. K. Ali, illus. Hatem Aly (2023). The Kindest Red: A Story of Hijab and Friendship. Andersen Press.

Newman, Lesléa, illus. Diana Souza (1989). Heather Has Two Mommies. Alyson Publications.

Nyong’o, Lupita, illus. Vashti Harrison (2021). Sulwe. Puffin.

Otter, Isabel, illus. Clara Anganuzzi (2021). Dear Earth. Caterpillar Books.

Percival, Tom. (2021) The Invisible. Simon & Schuster.

Scott, Jordan, illus. Sydney Smith (2021). I Talk Like a River. Walker Books.

Smithers, Anna, illus. Martyna Nejman (2021). Tree Full of Wonder. Orange Lotus Publishing.

Tan, Shaun (2010). The Red Tree. Hodder Children’s Books (Original work published 2001).

Thomas, Isabel, illus. Daniel Egnéus (2020). Fox: A Circle of Life Story. Bloomsbury Children’s Books.

Verde, Susan, illus. Peter H. Reynolds (2016). The Water Princess. G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers.

Williams, Karen Lynne, & Khadra Mohammed, illus. Doug Chayka (2007). Four Feet, Two Sandals. Eerdmans Books for Young Readers.