| Visual Thinking Strategies for Reading Engagement: Adapting Lessons from Denmark to English Language Learning

Shaun Nolan |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) were initially created to enhance skills in interpreting, describing, and analyzing art. This paper examines a state-funded pilot project in Denmark conducted by VTSdanmark, the organization that introduced VTS to the country and translated it into Danish from English. The project aimed to integrate VTS into the practices of librarians and language schoolteachers in Denmark and explore its impact on fostering children’s reading. Despite its small scale, findings suggest that VTS practice, through exploring visual narratives in images representing various children’s literary genres, sparks students’ curiosity and eagerness to read. It motivates students to read texts connected to visual images analyzed through VTS and empowers them by providing the language necessary to inquire further about these texts, fostering interest in reading and language acquisition. Building on the Danish project’s outcomes, this paper proposes applying VTS to motivate reading interest and language acquisition in English language learners (ELLs). The considerable potential of VTS’ impact on reading engagement, particularly for primary and lower secondary school students of English, warrants further investigation. This paper presents a versatile framework for implementing VTS in libraries and English language classrooms and details a research plan to evaluate VTS’ effectiveness in promoting reading engagement. The proposed framework is adaptable to various contexts and cultures, including the teaching of English as an additional language.

Keywords: children’s reading engagement, English language learning, research design, visual narratives, Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS)

Shaun Nolan holds a PhD in sociolinguistics and is a certified, experienced upper-secondary school teacher of English and French in Denmark. His research focuses on sociolinguistics within educational contexts, with recent work investigating the impact of Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) on language education.

Introduction

Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) is an inquiry-based pedagogical technique grounded in teacher-pupil discussions. It was originally developed in the Arts museum context in the United States in the early 1990s to improve museum visitors’ abilities to interpret, describe, and analyze imagery. This is achieved through active observation and collective discussion. Experimentation with and application of the technique from the period of its inception, especially in schools, has shown that VTS is impactful in fostering critical and creative thinking, visual literacy, language acquisition and communication (Nolan, 2022, 2023; Yenawine, 2013, 2018).

An important quality of VTS is the minimalist nature of the protocol through which it is applied. VTS is essentially centred on three scaffolding questions:

Q.1: What is going on in this… e.g. picture, image, text etc.?

Q.2. What do you see that makes you say that?

Q.3: What more can we find?

No other question is asked during a VTS facilitation session by the teacher, or facilitator in VTS parlance, than these three questions. Through its development since the 1990s and in accordance with the above-mentioned widening awareness of it potential impacts, VTS, as a student-centred pedagogical facilitation technique, is increasingly recognized for encouraging student engagement, equity and inclusiveness in the classroom. It is therefore gradually being used in various educational settings outside of museums, including schools and institutions of higher education, with children and adults of all ages. This usage is not just in art studies but also in health studies, mathematics, history, and language studies (Nolan, 2023; 2022; Yenawine, 2018, 2013).

In the context of English language teaching (ELT), Yenawine (2013, 2018) highlighted the positive impact of VTS in the English language classroom and how students’ oral and written communication skills improved after regular VTS sessions. Clark-Gareca and Meyer (2023) observed the use of VTS in English teaching and provided recommendations for its application to foster deeper engagement in the English language classroom. Dawson (2018) demonstrated how VTS can be used as a tool to engage students in evidence-based interpretation of a range of texts, starting with visual texts and progressing to written literary texts. Cappello and Walker (2016) utilized VTS for literacy development across various academic disciplines, including English Language Arts, helping students acquire and improve their close reading skills and academic vocabulary. These examples from the United States underscore the potential for applying VTS in English teaching as a first language or as a second language in a first language English-speaking context highlighting its benefits for literacy development.

Outside the United States, the use of VTS with English language learners (ELL) who learn the language as an additional language is still a burgeoning activity. For instance, Nolan (2022) analyzed the main language education policy documents in Sweden, the general Swedish curriculum for primary school education and the specific syllabi for English teaching in the context of the aims and practice of VTS. This analysis aimed to illustrate the alignment between VTS, and the overarching goals of Sweden’s educational framework, societal values, and specific objectives related to ELT. This study’s findings indicated that VTS has the capacity to effectively cultivate the precise abilities and skills delineated within the curriculum and English syllabus, such as language learning, critical thinking, and interpretative skills. These outcomes underscore the potential of VTS to enrich ELT practices in Sweden by harmonizing with the country’s broader educational aspirations.

In this paper, I explore how VTS can be used to promote an interest in reading in English and in doing so empower students by providing them with the language they need to talk about children’s literary genres that interest them. After reviewing VTS and its theoretical foundations, I focus on a pilot project in Denmark that used VTS to enhance reading engagement in the library and primary school language classroom contexts. This project, conducted by VTSdanmark – the organization that introduced and translated VTS into Danish from English – was conducted in Danish but was intended for application in any language, including English. The project provides a blueprint for professional training in VTS, which can be applied in primary or lower secondary school level education to promote student reading engagement and literacy growth in ELLs. I propose applying this training model through a versatile framework for training and adoption by librarians and teachers, specifically aimed at ELLs. Within this framework, I detail a flexible research design to fully investigate the impact of VTS on students’ reading engagement and literacy development in ELT.

The VTS Procedure, Observations of Practice and Theoretical Grounding

The three VTS questions provide a scaffolding which is appropriate to student participants’ initial level of understanding and knowledge related to a VTS facilitation focus object such as a picture. Beginner participants have shown that they are better able to apply their existing visual and cognitive skills to understand complex subject matter in a picture that has a strong narrative that they can relate to. In this way, the VTS session is grounded in the students’ own experiences and cognitive development, meaning the analysis comes from them and develops with them and their understanding (Nolan, 2022, 2023; Yenawine, 2013; Zieler & Abel Hesse, 2021).

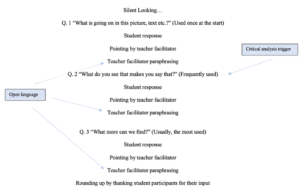

However, as students advance in their VTS exposure, other objects of focus can be used such as diagrams, sculptures, videos, and even mathematical equations, traditional written texts or multimodal texts. The VTS facilitation protocol is structured around the three questions. These questions form the backbone of the guided assistance and support system that is the VTS protocol. Before delving into these questions, students are given a moment of silent observation. This process enables students to focus on the image and gather their thoughts. Following this, the facilitation begins with the first VTS question, ‘What is going on in this image?’. This question, asked only once at the start, sets the stage for the discussion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A step-by-step illustration of the VTS facilitation protocol (adapted from Nolan, 2022, with permission)

During the VTS facilitation, the teacher points to the area of the picture that is referred to in each individual student comment and paraphrases these comments after each student has finished speaking. By using both pointing and paraphrasing, the teacher ensures that all students concentrate on the focus object content related to each comment. When paraphrasing, the teacher uses different terms from those in the student comments, creating a potential language learning moment. By providing alternative expressions, the teacher demonstrates various syntax and vocabulary possibilities, indirectly teaching by example (Yenawine, 2013). Yenawine (2013, p. 28) notes that anchoring words with images helps English learners expand their vocabulary. The teacher’s selected terms can include discipline-specific language, which can be used later by the student directly involved in the teacher–student exchange and by other students listening to this exchange. The paraphrasing language should also be open and inclusive in its formulation. For example, a teacher might paraphrase a student comment as follows: ‘You propose that these are four girls and a boy blowing bubbles in what you think is a farmyard,’ or ‘You suggest that these people might be a group of girls and a boy playing with bubbles in an area that looks like a farmyard’ (see Figure 2). This paraphrasing reflects the commentator’s words but leaves it open to interpretation by other students.

Figure 2. Sæbebobler (Blowing Bubbles) by H. A. Brendekilde (1906). Public domain artwork.

(This painting was used by a VTS trainee participant in the Danish pilot project.)

More encouragement for this reflection is provided by what could be described as the ‘critical analysis trigger’, namely, the second question. An example of this question in use could be the following: ‘What do you see that makes you think that these are girls blowing bubbles?’ or ‘What do you see that makes you think that this is a farmyard?’. The student participant is prompted to provide evidence for their previous assertions building on what they have already said and using the teacher paraphrasing. All the while, other student participants are looking, listening and thinking. The phrasing of this second ‘critical analysis trigger’ question offers a supporting guide for students to respond to the question by asking them about what they see, rather than posing a more potentially intimidating query like ‘why do you say that?’.

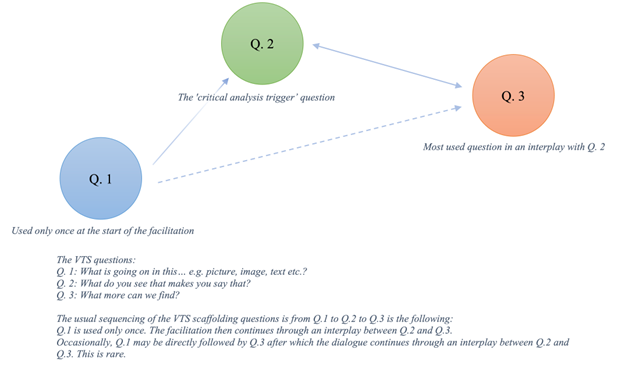

The third question, ‘What more can we find?’, is used as a follow-up to the second question. It is the most frequently used of the three questions, and its main value lies in reopening the discussion and inviting further student observations. These observations can either connect to previous comments or introduce completely new ideas. The wording of the third question is worth considering, as it is very natural in English to use ‘else’ instead of ‘more’ in such a question as in ‘what else can we find?’. This latter phrasing was used in Clark-Gareca and Meyer’s (2023) observed VTS session and presented as the wording of the third question. However, while both adverbs of degree suggest the possibility of discovering additional or alternative items, initial classroom field experiments in VTS revealed a significant difference in their impact. The use of the adverb ‘more’ stimulated a positive and dynamic interaction among participants. In contrast, the use of ‘else’ seemed to halt the conversation, implying that student participants might have overlooked something in their observations (Yenawine, 2013). Therefore, the recommended formulation of the third question in VTS is ‘What more can we find?’ because it has been proven to work better (Yenawine, 2013, 2018). See Figure 3 for an illustration of possible scaffolding question combinations during a VTS facilitation.

The teacher collectively thanks all students for their comments at the end of a VTS facilitation. This is both to show the value of all student participant comments and to maintain teacher facilitator neutrality (Yenawine, 2013; Zieler & Abel Hesse, 2021). This is the procedure which provides the basis of the VTS protocol.

Figure 3. Possible VTS question combinations.

The theoretical grounding of this pedagogical technique originates in the work particularly of cognitive psychologist Abigail Housen who was supported in this development by former Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) director of education, Philip Yenawine, in New York. Housen’s original work was in stage theory of aesthetic development during the mid-1970s (see Housen, 1980, 1983). This theory sought to understand how varying degrees of exposure to viewing works of art affected people’s viewing experiences. Her research methodology was based on the empirical approach that guided Piaget, Vygotsky, and Loevinger and describes the viewer’s experience of the visual world, and specifically of visual art. In the late 1980s, Yenawine was challenged by a major MoMA donor who wanted to know if their investment in the museum’s educational programmes effected change. This led Yenawine to collaborate with Housen and together they analyzed the effectiveness of MoMA’s programs (Yenawine, n.d.). The results of this analysis were that the MoMA education programmes of the time were not successful in effecting long term change in the aesthetic development of MoMA patrons. Housen and Yenawine then partnered in their work to develop a teaching approach to help MoMA patrons benefit more from their participation in the MoMA Art education programmes. VTS as a pedagogical tool grew out of this work. It is grounded in the cognitivist developmental learning theories of Dewey, Piaget, and especially the social constructivism most strongly associated with Vygotsky and Bruner (Hailey et al., 2015; Nolan, 2023; Yenawine, 2018, 2013).

As mentioned above, VTS discussions are anchored in the individual experiences and cognitive development of student participants. Analysis and insights emerge directly from the students themselves, reflecting their unique perspectives and interpretations. As Gogus (2012) articulates, knowledge and meaning are generated through lived experiences, learning processes, and the mental frameworks individuals use to understand the world. This constructivist approach acknowledges that understanding is built upon a foundation of prior knowledge, with new information integrated and reconciled with existing beliefs. The VTS approach, characterized by reciprocal interactions between students and teachers and active listening among students, is inherently social, sociocultural and linguistic in its nature.

Within the VTS context, individual perspectives are shared, challenged, and refined through dialogue and collaborative inquiry. This process aligns with the view that reality and its understanding are continuously shaped and reshaped through social interaction (Gogus, 2012). Theories of cognitive development, notably those of Dewey, Piaget, Vygotsky, and Bruner, emphasize the crucial role of culture and language in shaping understanding. Vygotsky (1986) and Bruner (1990), in particular, highlight the principles of social constructivism, where meaning-making is a dynamic process co-constructed through social interaction. Language serves as both a tool and a product of this process, with understanding continuously negotiated and restructured through dialogue. In the VTS facilitation, individual constructivism, with its emphasis on prior knowledge, is extended and enriched within a social constructivist framework. The VTS learning environment, facilitated by a teacher, encourages interactions among students, fostering a collaborative space where understanding, knowledge, and language evolve within each individual as a contributing member of the group.

The Desire to Read+VTS Pilot Project

In Denmark, the state promoted Læselyst initiatives are an important vehicle for the promotion of literacy among young people in the country. Læselyst (literally translated as ‘desire to read’) describes projects that research and promote literacy. Reinholdt Hansen, Illum Hansen and Pettersson (2022, p. 20) describe it for the purposes of their work as ‘development of interest’ (interesseudvikling) about reading. However, Hansen et al. (2022, p. 20) also refer to Romme Lund and Karskov Skyggebjerg (2021) in their description of læselyst as being ‘desire, joy, pleasure, enjoyment, attitude, interest, motivation, engagement, leisure, and recreation in relation to reading’ (lyst, glæde, fornøjelse, nydelse, attitude, interesse, motivation, engagement, fritid og rekreation i relation til læsning). The first appearance of the term læselyst appeared in the school syllabus for Danish as a school subject in 1984. It has since been developed to encompass a wide range of programmes to promote children’s literacy in Denmark though activities that encourage children to want to read (Hansen et al., 2022). The children themselves are the focus of læselyst and the basic premise behind the concept is that if children want to read, they will do so and as a result, their motivation, interest and engagement for reading and literature will increase, and their literacy will improve.

In 2019, Denmark’s national Ministry of Culture funded a pilot project aimed at demonstrating how VTS could foster a deeper engagement with text through the exploration of visual narratives, and by extension promote an interest in reading texts related to these visual narratives. The project was organized and carried out by VTSdanmark. It involved language teachers of Danish and librarians as VTS trainee participants. They were trained to use VTS to explore students’ interpretations of visual narratives with the goal of activating their curiosity and enjoyment of these narratives, which were then related to literary genres with the hope of stimulating a desire to read among these students.

The primary source of information about this project and its outcomes is a report made available at the end of the project (Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019). Lejre Library & Archive and Hvalsø Primary School (Lejre Bibliotek & Arkiv og Hvalsø Skole) in cooperation with VTSdanmark are responsible for this publication. It provides an account of the project’s progression and results. Additional details were provided through personal communications with the project’s organizers, VTSdanmark. This project was carried out in the town of Hvalsø, part of the greater Lejre municipality, situated to the west of Copenhagen in Zeeland, Denmark, during 2019. The project’s title was ‘Art communication as a tool for developing a desire to read’ (Kunstformidling som greb for læselyst [Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019], my translation). The term ‘art communication as a tool’ is synonymous with VTS. Consequently, in this paper, I have chosen to henceforth refer to this project in English as ‘Desire to Read+VTS’.

As a pilot project, Desire to Read+VTS was constrained in its potential and scope. Nevertheless, the execution of this initiative provides a promising blueprint that could be adapted and customized for similar projects across diverse cultural and linguistic contexts. Although the results are scientifically limited, they reveal a potential that warrants further exploration.

Desire to Read+VTS initially involved the training of three municipal librarians and three primary school teachers from Hvalsø in VTS. However, due to work pressures, this was eventually whittled down to two librarians and one teacher. Following a period of VTS initiation and training, this group of professional librarian and schoolteacher participants implemented VTS with students in the third to fifth grades, aged 9 to 12 years old. Desire to Read+VTS centred around images related to various children’s literary genres such as horror, science fiction, history and friendship in fiction. The project was executed from March 2019 to November 2019. The trainee participants took part in two comprehensive VTS workshops, the first in March and the second in May. The key themes of these workshops were as follows:

- Introduction to VTS emphasizing the importance of group dynamics and collaborative efforts,

- An advanced workshop aimed at deepening the understanding of VTS, with a particular focus on the selection of literary genres, images, and books.

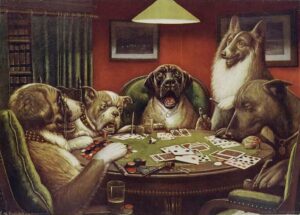

During the interval between the two workshops from March to May, the project team trainers and trainee participants convened on three separate occasions. These meetings were dedicated to honing librarian and schoolteacher participants’ VTS skills and engaging in discussions and reflections on the application of VTS to enhance a desire to read for students. During this ‘schoolteacher and librarian training phase’, the trainee participants started testing their VTS facilitating with student visitors to the library and in the classroom under observation by VTSdanmark. It was planned that in August a ‘Desire to Read+VTS laboratory’ would take place between trainers and trainee participants. This would further focus on trainee participant image selection. Trainees were to independently select five pictures corresponding to different literature genres with the selection of five books for each of these different genres. Sæbebobler (Blowing Bubbles) by H. A. Brendekilde in Figure 2 is an example of one of the five pictures proposed by one trainee participant. In English, this could correspond to Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables in the friendship book genre. In Figure 4, there is another example of a trainee selected picture, ‘A Waterloo’ by Cassius Marcellus Coolidge. This was chosen to represent animals in fiction genre such as Erin Hunter’s Warriors book series (VTSdanmark, personal communication, 28 August 2024).

Figure 4. ‘A Waterloo’ by Cassius Marcellus Coolidge. Public domain artwork.

It was at this point that the pilot project ran into some timetabling and availability issues for trainees that for some became insurmountable. As a result, two librarians and one teacher were able to commit themselves to the project to the end and the Desire to Read+VTS laboratory was scheduled for the beginning of October. Subsequently, the next phase of Desire to Read+VTS, the ‘VTS student sessions phase’, took place during the remainder of October into November with the curated content from the Desire to Read+VTS laboratory. This phase entailed three facilitating sessions with different student groups of up to 20 students by each of the remaining trainee participants in Hvalsø public library and primary school. Between these nine facilitations, up to 180 students from third to fifth grades, from 9 to 12 years old, experienced VTS (VTSdanmark, personal communication, 15 June 2024).

Finally, a ‘book stacks phase’ took place. In both the public library and the primary school, after the VTS sessions, students were introduced to stacks of books with overarching themes that corresponded to new but similar pictures to those they had experienced in VTS. These new pictures were placed on the book stacks to attract student attention (Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019).

What We Can Learn from Desire to Read+VTS

The findings of Desire to Read+VTS stem from the experiences of the librarians and schoolteachers who participated in the project, as detailed in the above-mentioned post-project report (Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019). These findings can be summarized in the following manner:

- Participating students were drawn to the book stacks’ pictures and autonomously applied VTS to these pictures and subsequently showed more interest in the books.

- There was an increase in students’ curiosity about things they were already familiar with. But they also showed curiosity for new interests.

- VTS used with images related to literary themes and genres appeared to make students more assured and focused on their choice of books and they appeared more precise in being able to communicate their needs. They acquired the language to speak about what they wanted to read.

- For trainee librarians and the schoolteacher, VTS as an art communication tool appeared natural to use in the promotion of interest in books.

- The trainee librarians and the schoolteacher clearly indicated their desire to use VTS as a tool for motivating reading in their daily work in the future.

The schoolteacher and librarian trainee participants reported a significant exchange of insights regarding children’s literature between the primary school and library throughout the project. This cross-disciplinary cooperation approach to learning and using VTS has laid a solid foundation for tangible collaborations. One librarian trainee participant noted: ‘The project has fostered an excellent partnership between the school and library, which could be further enriched by expanding the use of VTS’ (my translation, Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019, p. 6).[i] A practical example of this cooperation was the experience of the teacher trainee participant from Hvalsø Primary School who shared that after their VTS facilitations, the students were asked to select books in the library that they felt corresponded with the focus image of the VTS classroom session. The teacher observed that ‘several students borrowed the books from the library afterwards. I believe their senses were honed, and they concentrated on the content and details in the images, which subsequently influenced their book selection’ (my translation, Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019, p. 5).[ii]

The above-mentioned independent use of VTS by students demonstrates how participants, with increased exposure to VTS facilitation, tend to adopt and apply its three scaffolding questions as an analytical tool in their everyday lives. This has been attested to in other places in which VTS has been used within education contexts such as in the United States (see Yenawine, 2013) and in Denmark (see Nolan, 2023).

Prior to the project, both librarians and teachers noted the challenges faced by children in the 9 to 12 years old age group in both determining what they want to read and talking about this. After these VTS facilitations, the students knew what they wanted to ask for in the library. In this way, there was a language learning moment as mentioned above in that the students here learned the specific language they needed to express their needs through the paraphrasing. This language learning has proven to be an integral part of the VTS experience as shown in Yenawine (2013, 2018) and in Nolan (2023) and is an important part of its attraction for English language teaching (see Nolan, 2022; Clark-Gareca & Meyer, 2023).

When participants from both the primary school and public library shared their plans to integrate VTS into their work, the librarians expressed their intention to utilize it during events such as book talks, readings, or when hosting school classes at the library. All trainees expressed an interest in further investigating how VTS could be used more directly with books e.g., applying VTS to illustrations or pictures in a book when guiding the children in choosing books. The schoolteacher trainee specifically expressed the following:

In a time when reading receives less and less attention, it is important to focus on what it is that can capture and boost the desire to read (…). I myself have become more aware of the images and tools in literature in relation to advising students – VTS has become a tool for conveying images in a different way for me than classical image analysis (my translation, Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019, p. 6).[iii]

Beyond active facilitation, trainees suggested displaying the three VTS scaffolding questions alongside books. According to them, this approach encourages visitors to the library or school students in the classroom to ask questions, sparking curiosity and thereby promoting a deeper exploration and reading of the materials (Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019).

Awareness of the utility of VTS in image-dominated, multimodal, or even written text-dominated literature is well-established. VTS can be effectively applied to both wordless picturebooks (WPBs) and picturebooks with text. When used with WPBs, VTS leverages visual storytelling elements to engage readers in deep, interpretive conversations. In picturebooks with written text, Lambert (2020) incorporates VTS with younger children as part of The Whole Book Approach, using the inquiry-based essence of VTS to facilitate ‘co-constructive’ storytimes, characterized by extensive discussion during the reading of the book (p. xix). Lambert (2020) notes: ‘As I learned more about VTS and dialogic reading, I was encouraged by the research-based evidence supporting the practice of stopping and discussing a book during reading to enhance comprehension, engagement, vocabulary acquisition, and literacy skills (p. xx).’ However, Lambert (2020) contrasts dialogic reading, often referred to as ‘hear and say reading’, where children respond to something read aloud or a related question, with The Whole Book Approach, which she describes as ‘see, hear, and say reading’ (p. xxi). This approach emphasizes VTS style questions and prompts a focus on the illustration, design, and production elements of the picturebook as an art form. Thus, VTS supports The Whole Book Approach in fully exploiting the multimodal qualities of picturebooks.

VTS can also be effectively applied to (written) text-dominated literature for older children, particularly those aged 9 to 12 years. VTS can be used as a pre-reading exercise by analyzing a picture related to the book’s topic or visual elements such as its cover, in a manner similar to the Desire to Read+VTS project. Furthermore, according to VTSdanmark (personal communication, 15 October 2024), a natural progression from the Desire to Read+VTS project involves applying VTS to understand and analyze the accompanying written text. The skills of observation, critical thinking, and discussion that VTS fosters through visual art are transferable to literary analysis. The above-mentioned research by Yenawine (2013), Dawson (2018), and Capello and Walker (2016) has shown that VTS enhances the critical thinking and reasoning skills necessary for reading comprehension and for analyzing complex literary texts. For example, teachers can use the VTS questions to guide students through a text in the following manner:

Q.1: What is going on in this text/page/chapter/book?

Q.2: What do you see in the text/page/etc. that makes you say that?”

Q.3: What more can we find in the text/page/etc.?

The direct use of VTS with written text is a highly compelling progression from the Desire to Read+VTS project’s focus on exploring visual narratives in images representing children’s various literary genres, thereby motivating a desire to read. This demonstrates the project’s extensive potential. Desire to Read+VTS transitions this visual literacy analysis protocol from the art museum into the language and literacy education environment. As a result, it provides language and literature students with a solid foundation in visual literacy, which can then be more easily and naturally applied to other types of text.

Evaluating Desire to Read+VTS and Next Steps

Did the Desire to Read+VTS pilot project show that students’ curiosity and enjoyment of visual narratives stimulates a desire to read through VTS? And did it show that it can empower them by providing them with the language to enquire about these texts? The findings as described by the trainee participants in the post-project report appear to indicate that the answer is yes to both questions.

These findings also suggest that even a small-scale pilot project like this one can yield important information, despite encountering significant challenges during its implementation. Notwithstanding these challenges, the results in increasing student participants’ desire to read and linguistically enabling them to do so appear positive. The final group of trainee participants’ enthusiasm to continue in the use of VTS in their daily work was established, and other results further confirmed students’ empowerment through independent use of VTS and language learning corresponding to observations elsewhere (see Yenawine, 2013, 2018; Nolan, 2023). This small-scale Danish pilot project not only fulfilled its objectives, but also sparks consideration of the feasibility and viability of applying this model in future projects in diverse locations.

It is important to acknowledge the pilot study’s limitations. For example, the small number of professional trainee participants, the reliance solely on their feedback at the project’s conclusion for findings, and challenges encountered during the project’s execution. However, this is the point of a pilot project. As observed by Oliver (2003, p. 37, as cited in Cohen et al., 2018, p. 136), a pilot study can be useful to judge the effects of a piece of research on participants. The successful completion of the project, coupled with the enthusiasm of the trainee participants noted in its final stages, suggests that further development in a Desire to Read+VTS project is not only feasible but also potentially highly valuable to relevant professionals working with children’s literacy. Cohen et al. (2018, p. 204) point out that in ethnographic or qualitative research such as this, it is more likely that the sample size will be small and therefore the size of the pilot study does not diminish its value. Even with a small number of participants, a pilot project can provide valuable insights that can guide the design and implementation of subsequent studies. The implementation of lessons learned will vary depending on the context and specifics of future projects. However, substantial benefits can be gained from considering the challenges and successes of the Danish Desire to Read+VTS pilot project particularly in terms of project structure, risk mitigation, feasibility assessment, and the process of data collection and their evaluation.

A Framework for Further Implementation and Research in an ELT Context:

Desire to Read+VTS for ELLs

The feasibility of future projects is further bolstered by viewing the Danish pilot project as a testing ground for VTS adoption. Future Desire to Read+VTS projects could be modelled after the framework presented in Figure 5, focusing on utility for ELLs. This proposal synthesizes this paper’s examination of the Danish pilot project, considering its successes, shortcomings, and lessons learned. The Desire to Read+VTS for ELLs proposal aims to incorporate the lessons learned from the Desire to Read+VTS pilot by outlining all potential participants and events, enhancing data collection tools and identifying all potential data collection sources. This comprehensive view aids in determining the necessary resource management for different participant groups in a larger-scale project, leading to more effective planning and resource allocation.

For the purposes of this new project framework, the essential trainee participant category is English language teachers. Librarians are also included to acknowledge their important role in youth literacy development within a school or community education context. However, the project framework remains executable even if librarians are unable to participate. The selection of target student groups in English as an additional language should consider the number of years that students have been learning English. In countries such as Denmark and Sweden, students aged 10 years or older (primary school grade 4) may have in some schools up to 4 years of English learning and so should be able to benefit from VTS in English with the primary objective of motivating reading engagement.

The quality of data and its potential enhancement through Desire to Read+VTS for ELLs’ collection instruments is crucial. In Figure 5, the use of personal journals or diaries which are proposed to collect observational data from both trainee participants and VTS trainers, supplemented by interviews with trainees, could offer significant benefits (Cohen et al., 2018). Additionally, soliciting feedback from students about their VTS experiences and its impact on their interest in reading would provide further valuable insights. This triangulation of multiple forms of data from different actors in the project bolsters its reliability and validity (Cohen et al., 2018). A further source of data collection for consideration could be the recording and transcription of VTS sessions to evaluate both professional trainee VTS facilitator and student progress during these sessions.

In risk mitigation and resource management, it is crucial to identify and address potential issues or challenges before they escalate in subsequent studies. The Desire to Read+VTS pilot project pinpointed a significant issue for the professional trainee participants – their availability throughout the project’s duration. This can be mitigated by ensuring these professionals are fully informed about the project’s planning details and understand the need to align their work schedules accordingly. It is equally vital that their workplace’s management is cognizant of the commitment required for such a project and agrees in advance to allow their staff’s full participation, providing the necessary support. To prevent such commitments from intimidating either the trainee participants or their managers, the benefits of participation should be emphasized – for the trainee participants’ professional development, their workplaces, students, and society at large. The results of the Desire to Read+VTS pilot provides considerable support for this argument.

Figure 5. A Desire to Read+VTS for ELLs project model.

Concluding Remarks

The pilot project in Denmark was never followed up. According to the organizers, this was mainly due to the impact of the Covid19 pandemic in the immediate aftermath of the project. Subsequently, other obstacles have also played a role, including the participants’ professional commitments (VTSdanmark, personal communication, 15 June 2024).

I believe that this is a missed opportunity, and this especially given that to date there does not appear to have been a systematic and coordinated study to evaluate VTS for its potential influence in motivating student reading literacy. This is surprising, considering that educators in the United States have employed VTS in diverse manners in English language and literature classrooms (Yenawine, 2013, 2018; Dawson, 2018). It can therefore be stated with some certainty that, aside from Desire to Read+VTS in Denmark, the potential impact of VTS explorations of visual narratives in images for encouraging engagement with reading as a primary objective has not been the basis of any formal studies to date.

The Desire to Read+VTS pilot project has demonstrated its potential for further investigation. This is to assess how VTS could act as a catalyst for the creation of more inclusive and effective literacy initiatives by using VTS to encourage reading engagement. The VTS technique offers a pedagogical structure that immerses students in the narratives found within images and in this case, by extension literature, stimulating their curiosity about these stories. The VTS experience provides them with the language they require to seek the literature that interests them and encourages them to engage with this reading and to delve deeper, thereby fostering their literacy skills.

Moving forward, it would be advantageous to broaden the Desire to Read+VTS project’s scope in the manner proposed through Desire to Read+VTS for ELLs in Figure 5. This framework could be used and adapted by librarians and educators to promote VTS at their respective institutions. It could involve including a wider variety of trainee participants who can, as mentioned above, remain committed throughout the project’s duration, working with larger student groups over an extended period, and conducting more VTS facilitations during the ‘2nd VTS student sessions phase’ as proposed in Figure 5. Moreover, careful consideration of data collection instruments would allow researchers to refine data collection procedures and progress beyond relying solely on professional trainee participant feedback at the project’s conclusion as was the case in the Danish project. These steps would further enhance our understanding of the role that VTS can play in promoting reading engagement. Such adjustments would not only strengthen the reliability and validity of the results but also offer a more holistic view of VTS’ potential impact in empowering students in a literary environment and motivating these students to read.

References

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Cappello, M., & Walker, N. T. (2016) Visual thinking strategies: Teachers’ reflections on closely reading complex visual texts within the disciplines. The Reading Teacher, 70(3), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1523

Clark-Gareca, B., & Meyer, T. (2023). Visual thinking strategies for English learners: Learning language through the power of art. TESOL Journal, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.698

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315456539

Gogus, A. (2012). Constructivist learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 783–786). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_142

Dawson, C. (2018). Visual thinking strategies in the English classroom: Empowering students to interpret unfamiliar texts. Voices From the Middle, 26(1), 44–48.

Hailey, D., Miller, A., & Yenawine, P. (2015). Understanding visual literacy: The visual thinking strategies approach. In D. Baylen, & A. D’Alba (Eds.), Essentials of teaching and integrating visual and media literacy (pp. 49–73). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5_3

Hansen, R. S., Hansen, T. I., & Pettersson, M. (2022). Børn og Unges Læsning 2021. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Housen, A. (1983). The eye of the beholder: Measuring aesthetic development [Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University]. Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Housen, A. (1980). What is beyond, or before, the lecture tour? A study of aesthetic modes of understanding. Art Education, 33(1), 16–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/3192394

Lambert, M. D. (2020). Reading picture books with children: How to shake up storytime and get kids talking about what they see. Charlesbridge.

Lejre & Hvalsø (2019). Kunstformidling som greb for læselyst (Lejre Bibliotek & Arkiv og Hvalsø Skole i samarbejde med VTSdanmark). Projektet støttet af Kulturministeriet, Slots- og Kulturstyrelsens Udviklingspulje for folkebiblioteker og pædagogiske læringscentre.

Lund, H. R. & Skyggebjerg, A. K. (2021). Børns læselyst: En forskningsoversigt. Aarhus Universitetsforlag. Pædagogisk Indblik Bind 13. www.dpu.au.dk/viden/paedagogiskindblik/boerns-laeselyst.

Nolan, S. (2023). Visual thinking strategies as a pedagogical tool: Initial expectations, applications, and perspectives in Denmark. Journal of Visual Literacy, 42(3), 210–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2023.2261222

Nolan, S. (2022). VTS in the English language classroom in Sweden: Visuality, paraphrasing and collective thinking in support of language learning. Educare, (4), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.24834/educare.2022.4.6

Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language. MIT Press.

Yenawine, P. (n.d.). Permission to wonder. Philip Yenawine. https://www.philipyenawine.com

Yenawine, P. (2018). Visual thinking strategies for preschool: Using art to enhance literacy and social Skills. Harvard Education Press.

Yenawine, P. (2013). Visual thinking strategies: Using art to deepen learning across school disciplines. Harvard Education Press.

Zieler, A., & Abel Hesse, M. (2021). Visual thinking strategies – at støtte elever i at sætte ord på det, de ser. In M. S. Kaa Sunesen, & D. Dalum Christoffersen (Eds.), Elevperspektiver (pp. 189–203). Forlaget Klim.

[i] ‘Projektet har skabt et virkelig godt samarbejde mellem skole og bibliotek, som kunne være rigtig

interessant at udfylde meget mere med udgangspunkt i VTS’ (Librarian from Hvalsø Primary

School, Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019, p. 6).

[ii] ‘[…] der var flere der lånte bøgerne bagefter. Jeg synes deres sanser blev mere skærpet og de

fokuserede på indhold og detaljer i billederne som de så kunne bruge I forhold til deres valg af

bøger’ (schoolteacher from Hvalsø Primary School, Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019, p. 5).

[iii] ‘I en tid hvor læsning får mindre og mindre opmærksomhed er det vigtigt at fokusere på hvad det

er der kan fange og “booste” læselysten (…) jeg er selv blevet mere opmærksom på litteraturens

billeder og virkemidler i forhold til rådgivning af elever – VTS er blevet et redskab til at formidle

billeder på en anden måde for mig end klassisk billedanalyse’ (Schoolteacher from Hvalsø Primary

School, Lejre & Hvalsø, 2019, p. 6).