| Authenticity in Representation: A Critical Analysis of Illustrations in Picturebooks for Elementary School Students

Aniqa Shah |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Picturebooks are often children’s first introduction to literature and play a significant role in shaping their understanding of the world. Beyond vocabulary acquisition, these books impart social values, gender roles, relationship dynamics, and character traits such as kindness and generosity. Unfortunately, they can also reinforce biases and stereotypes. This analysis examines six picture books authored and illustrated by non-Muslim writers, focusing on their visual elements – including lines, shapes, colours, light, and focus – to explore how Muslims are represented. The findings reveal that certain negative portrayals commonly found in mainstream media, such as depictions of Muslims as backward, war-torn, depressed, and deficient, are also present in children’s literature. The analysis highlights the need for more authentic and nuanced representations of Muslim characters in children’s books, as these portrayals could combat the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes.

Keywords: authentic representation, critical reflection, cultural sensitivity, stereotypes

Aniqa Shah is a PhD candidate in the department of Teaching, Learning & Sociocultural Studies, University of Arizona, with a minor in Second Language Acquisition Theory. Aniqa has taught several undergraduate level courses at the University of Arizona focusing on teaching multilingual learners and has also been involved in various K-16 teacher education projects.

Introduction

A picture speaks a thousand words – even more so when it appears in a picturebook. Yet the interpretation of images is complex and deserves careful consideration. In his 1977 essay ‘Rhetoric of the Image’, Barthes warned against interpreting images in isolation, considering them too polysemous to stand alone. Present-day scholars argue that illustrations can be even more powerful than text (Anderson, 2002; Broadway & Conkle, 2010), particularly for children whose reading skills are not sufficiently developed for them to be drawn to the words, as illustrations deliver the story for them. This paper reviews six picturebooks representing Muslims as a minority group and examines potential biases that may have consciously or unconsciously influenced their illustrations.

For this review, I selected books that tell their stories through both illustrations and words. Artists and illustrators invest considerable thought and effort in crafting images that communicate powerfully with their audience, employing various visual elements and design features as strategies to deliver content. Since visual experiences are unique and cannot always be verbally conveyed (Salisbury & Styles, 2020), even the smallest details in illustrations result from careful deliberation and research. As young children do not ‘naturally and automatically’ (Richards & Anderson, 2003, p. 442) notice subtle aspects of illustrations, this paper focuses on prominent, recurring elements rather than delving deeply into visual grammar (Serafini, 2014). The analysis examines how various visual elements such as colours, lines, angles, and other compositional features work together to create meaning and convey cultural representations.

This study focuses specifically on works by non-Muslim writers and illustrators to investigate whether negative representations of Muslims in Western mass media also appear in children’s picturebooks. The relationship between media representation and cultural understanding is particularly significant given the increasing diversity portrayed in children’s literature and the ongoing discussions about authentic representation. While some research has examined picturebooks featuring Muslims by analyzing both text and images, few studies have focused exclusively on illustrations and their role in shaping cultural narratives. This study aims to address this gap through detailed analysis of visual elements.

It must be emphasized that this paper is not intended as a critique of the picturebooks or their illustrators. To respect the artists’ work, each analysis begins by highlighting the skill and expertise of the artists involved. The aim of this paper is not to criticize but to examine the subtle ways in which misrepresentations of cultural or religious groups may unintentionally appear in children’s books. This analysis seeks to uncover how even well-intentioned works may perpetuate stereotypes or biases, despite the accomplished work of their creators, and how visual elements in picturebooks can either challenge or perpetuate existing cultural narratives and stereotypes.

In the following sections, I present a brief literature review examining current scholarship on visual representation in children’s literature, followed by the theoretical underpinnings of my analysis. The methodology section details the criteria for book selection and the analytical framework used to examine the illustrations. I then provide descriptions of the reviewed books’ illustrative features, coupled with my observations and interpretations as a Muslim reader. Throughout the analysis, I highlight both strengths and weaknesses of the illustrations in terms of how they helped me construct meaning and how I could recognize representations of myself, my religion, and my community’s history. The paper concludes with a discussion of the findings and their implications for the broader conversation about cultural representation in children’s literature and their use in classrooms.

Theoretical Framework

Critical race theory situates race at the centre of issues of injustice and misrepresentations. It recognizes that racism is often hidden behind the guise of ‘normality’ and thus goes unnoticed until the oppression perpetuated by racism takes an obvious negative form (Gillborn, 2015). This is significant today more than ever given the common assumption of society having arrived at a ‘post-racial era’ (Mills & Unsworth, 2018). Racism, by its very definition, seeks to create social and material division in society (Bell, 1992; Delgado & Stefancic, 2001). In the light of critical race theory, issues of representation become all the more potent. Racism is so prevalent that it can be found and experienced ‘anywhere and everywhere’ (Huber & Solorzano, 2015) and often manifests through the prevalence of stereotypes (Spoonley, 2019). One of the solutions for addressing these misleading representations suggested by critical race theorists has been counter-storytelling (Mullins, 2016). Advocates of critical race theory propose counter-storytelling as a way of combating the dominant discourse (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001; Mullins, 2016; Solorzano & Yosso, 2001; Solorzano & Yosso, 2002). Solorzano and Yosso (2002) define counter-storytelling as a method to give voice to the ones whose stories have either not been told or have been distorted. They also see it as a tool to expose, analyse, and challenge ‘the majoritarian stories of racial privilege’ (p. 32). It is imperative that these stereotypes in children’s literature are identified so that other books can serve as counter-stories, facilitating acceptance versus othering.

Literature Review

Research on children’s literature has been expansive and diverse. From an analysis of the use of words and language in picturebooks and the impact on children’s language learning (Montag et al., 2015) to the depiction of serious themes like racism and feminism (Crisp & Brittany, 2011; Kérchy, 2014; Wiseman et al., 2019), the studies have been wide-ranging. Some examples of this multi-dimensionality include the role of place in children’s picturebooks (Manolessou & Martin, 2012), blindness as a theme in children’s picturebooks (Hughes, 2012), picturebooks about death and dying (Wiseman, 2013) and the use of maps and narratives in children’s picturebooks (Meunier, 2017). However, ironically, there hasn’t been much research on how certain religious and cultural groups have been represented in children’s literature, Muslims being one such group whose representations have largely been overlooked (Torres, 2016). Content analysis on representations of Muslims include work done by Raina (2009), Aziz (2012), Aziz (2019), Torres (2016), Schmidt (2016), Liou and Cutler (2020), and Mehmat and May (2020). Out of these studies, Schmidt (2016) and Aziz (2019) look at images specifically and find that they confirm prevalent stereotypes against Muslims.

Aziz’s (2009) dissertation study focused on the representations of Muslims in postcolonial texts. She examined 72 children’s and young adult books published and distributed in the USA. One of the sections in her dissertation focused on the representation of varied Muslim cultures in contemporary realistic fiction, historical fiction, and biographies. Another section looked at the influence of authors’ and illustrators’ background on the way they crafted the identities of Muslims in their books. She found that most of these writers/illustrators did not identify as Muslims and fell into the trap of writing about this group in line with the Western narrative. In Raina’s own words, numerous books published in the USA about Muslims ‘reflect surface level information on the varied Muslim cultures reflected’ (p. 171). Torres (2009) examined a set of 56 picturebooks to assess which ones contribute to the development of a positive image for Muslims and which play a part in ‘othering’ them (p. 193). Her analysis confirmed a dearth of books that do justice to the cultural diversity of Muslims. The only study that paid attention to the images of Muslims in picturebooks was conducted by Schmidt (2006). She analyzed 15 books published between 1979 and 2004 to identify the ways in which visual images portray Arabs. Some of the categories that she used to categorize her data were: veiled Islamic traditionalists, faceless, tribal and war-loving. Her findings confirmed that racial stereotyping is perpetuated along these categories (and more) through books.

Aziz’s work (2019) relates closely to the task I am attempting in this study. She critically analyzed the ‘visual images in four graphic novels set in Iran, Libya, Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon’ (p. 208) and concludes that each graphic novel paints a Middle Eastern society that is frozen in time, where oppression is the norm.

With Islamophobia on the rise (Susie, 2016), misrepresentation and under-representation of Muslims in media and literature is common (Punjawani, 2020). Misrepresentation has been so extreme that Mastracci (2016) concluded that the New York Times ‘portrays Islam more negatively than cancer’. Picturebooks written for young children often present a ‘single, generalized representation of Islamic life, and elements that contribute to the othering and misrepresentation of Muslims’ (Torres, 2016). A few scholars have come forward to address this gap in research, fully convinced that one effective way to deal with Islamophobia is by introducing children’s literature that promotes empathy for Muslims in classrooms (Albalawi, 2015; Newstreet et al., 2019). Content analysis of picturebooks written by non-Muslim authors often represents Muslims as either in a constant state of war or still complacently practising ancient customs (Mehmat & May, 2020). Muslim women are often shown as subjugated, suppressed and unhappy (Aziz, 2012). Wiseman et al. (2019) voiced their concerns about the way Muslim children were depicted in the picturebook Layla’s Headscarf. Bang and Reece (2003) looked at how images on television commercials for children portray minoritized groups. They concluded that children who are repeatedly exposed to specific images about a cultural group come to hold similar beliefs about that cultural group. It is of utmost importance that children be exposed to literature that promotes positive stories about Muslims and care be taken to not represent them in a way that fossilizes these stereotypes (Gauri & Siddique, 2018).

Methodology

My selected books are English-language picturebooks targeting pre-teens, with three designated as ‘adult-directed’. Moreover, I specifically sought works neither written nor illustrated by Muslims. With these two parameters in mind, I browsed through collections of picturebooks and selected six representative titles for analysis: My Beautiful Birds by author/illustrator Suzanne Del Rizzo (2017), Muhammad by author/illustrator Demi (2003), Silent Music: A Story of Baghdad by author/illustrator James Rumford (2008), Traveling Man: The Journey of Ibn Battuta 1325-1354 by author/illustrator James Rumford (2001), The Carpet Boy’s Gift by Pegi Deitz Shea, illus. Leane Morin (2003) and Ziba Came on a Boat by Liz Lofthouse, illus. Robert Ingpen (2007). In conducting this review, I maintained a strict focus on illustrations and avoided textual analysis.

My focus on non-Muslim authors and illustrators serves to control variables and differs from earlier research noted in the literature review, which took a more holistic approach. Additionally, this selection allows examination of whether illustrators who do not identify as Muslim have been influenced by popular media and news reports in their representations. Drawing on Bishop’s (1990) concept of children’s literature serving as ‘windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors’, I examined whether Muslims could see themselves reflected in these books (mirrors) and whether they provide appropriate windows and sliding glass doors for non-Muslim audiences. My analysis is grounded in Rosenblatt’s (1982, 1994) transactional theory of reading. As a reader, I brought my Muslim identity to these books, and my analysis heavily reflects ‘what the work communicated’ to me (Rosenblatt, 1994, p. 30). My voice as a Muslim reader serves as a critical analytical tool, offering insights that might not be apparent to those outside of Muslim circles. The analysis has been derived through the methodology of critical content analysis, which examines power dynamics in social practices to identify and challenge conditions perpetuating inequity (Short, 2016). This approach requires examining texts through a particular theoretical lens, with scholars recommending at least two readings: first as a general reader, then as a researcher conducting close analysis.

This paper addresses questions of cultural authenticity, examining the picturebooks through an insider’s lens to evaluate whether their portrayal of Muslim cultural contexts aligns with my ‘sense of truth’ and believability (Short & Fox, 2004, p. 373). My status as a Muslim and firsthand knowledge of Muslim cultural identities serves as the foundation for this analysis. To provide context for my perspective, I was born and raised as a Muslim in Pakistan. Since I do not come from a deeply Muslim family, my religious knowledge and practice stem from personal inquiry rather than mere inheritance. My experience traveling within the Muslim world, combined with my ongoing engagement with news and cultural developments in Muslim communities, provides me with both deep and broad knowledge to evaluate the authenticity of Muslim representations in books and popular media. This personal background, combined with my academic training, allows me to use my voice not just as a tool of critique but as an instrument of cultural interpretation and analysis.

Analysis of the Picturebooks

The first book examined in this study was My Beautiful Birds by Suzanne Del Rizzo (2017), which tells the story of a young boy, Sami, who escapes with his family from Syria and temporarily settles in a refugee camp. While other children in the camp begin to adjust to their new routines, Sami remains preoccupied with the loss of his birds and the joy he once found in tending to them before the war. Upon opening the book, readers are greeted by a colourful spread of endpapers. Since endpapers are often considered ‘visual overtures to the art of the book’ (Lambert, 2015, p. 26), they immediately convey a sense of hope, using bright shades in an ensemble of images. Unlike typical war and refugee books, which often feature sombre tones, the endpapers render a more positive, hopeful feeling. The illustrations in My Beautiful Birds are powerful and impactful, created with paint, Plasticine, and clay, to craft highly textured illustrations with a tactile, lifelike quality that the reader cannot ignore.

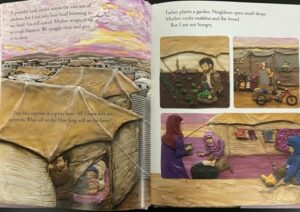

However, one significant issue in My Beautiful Birds is the depiction of young girls wearing hijabs. In Islamic tradition, girls typically do not begin wearing the hijab until they reach puberty, as it is viewed as a symbol of modesty. However, in this book, young girls are shown wearing hijabs even while playing or asleep in bed (Figure 1), which misrepresents this religious practice. While the intent may have been to reflect Muslim identity, this portrayal inadvertently reinforces a misunderstanding about the obligation of hijab. It could lead young readers to assume that all Muslim girls wear the hijab from a very early age, overlooking the cultural and religious context in which the practice begins.

Figure 1. Spread from My Beautiful Birds by Del Rizzo, showing little girls with headscarves. Excerpted from My Beautiful Birds by Suzanne Del Rizzo, copyright © 2017. Reprinted with the permission of Pajama Press. All rights reserved.

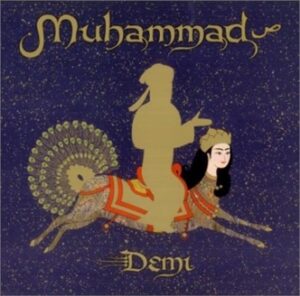

The second book in this analysis is Muhammad (peace be upon him) by Demi (2003). All the illustrations in the book are framed with ambient margins in shades of yellow and gold, which are interestingly varied in size and orientation as the book progresses. Some images breach their frames, creating a sense of closer connection between the reader’s world and the story world (Painter et al., 2013, p. 107). The Prophet (peace be upon him) has been painted as a silhouette in gold, without showing any facial features (see Figure 2). Demi’s choice to depict the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) using gold without facial features reflects an attempt to respect the Islamic tradition of avoiding direct depictions of the Prophet. While this approach is commendable, it is important to note that, according to Islamic traditions, even an abstract or indirect representation – such as a silhouette – can still be viewed as inappropriate (Mehmat & May, 2020). The intention to honour the Prophet is clear, but in Islamic belief, any visual representation, even one that is abstract or respectful, can be seen as diminishing the reverence due to the Prophet (peace be upon him). Therefore, while the illustrator’s effort is appreciated, some readers may find even the silhouette problematic from a religious perspective.

A bigger issue within this picturebook is the depiction of angels. In Islamic theology, angels are considered beings crafted from God’s light, without human-like physical bodies or faces. They may take on bodily forms to communicate with people, but they do not possess human features. However, in Demi’s illustrations, the angels are shown with distinctly human-like traits, which deviates from traditional Islamic teachings. Furthermore, their portrayal strongly resembles depictions of celestial beings in Hinduism, which, as a practising Muslim, I found concerning. Accurate representation of angels is essential in works centred on the Prophet (peace be upon him) and Islamic tradition, as belief in angels is a fundamental tenet of the Muslim faith.

Figure 2. Front cover of Muhammad by Demi, © 2003, published by Margaret K. McElderry Books.

A comment on the Bibliocommons website echoes my concerns, stating: ‘I believe that the cover-page is so strange that I can’t even describe it. On one side, it’s about Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him), and on the other side, the horse has the head of an Indian god. Seriously, if the author thinks they know about Prophet Muhammad (SAW), they wouldn’t choose this picture’ (https://burlingame.bibliocommons.com/v2/record/S76C1056894). This critique highlights a significant disconnect between the book’s depiction and the religious sensitivities of the group of audience that most closely identifies with the represented religious group.

The next picture book analyzed was Silent Music: A Story of Baghdad, written and illustrated by James Rumford (2008). This beautifully illustrated book tells the story of a young boy, Ali, from Baghdad, Iraq, who has a passion for both soccer and calligraphy. The illustrations are filled with elements of Arabic calligraphy on nearly every page, blending both art forms into the narrative. The first double-page spread presents a vivid snapshot of the Middle Eastern landscape, with a mosque’s dome and palm trees. The use of yellow in the background, contrasting with the dark silhouettes of the mosque and palm trees, evokes a sense of foreboding. However, the mood shifts as the next page introduces Ali, holding a soccer ball and ready to play with his friends. The close-up of Ali looking directly at the reader creates an immediate, personal connection. As the story unfolds, the illustrations continue to weave together vibrant colours and intricate designs, blending English text with Arabic calligraphy, effectively showcasing Muslim art and culture.

While these artistic choices are impressive and may serve to familiarize Western readers with elements of Islamic art, it can unintentionally reinforce stereotypical portrayals of the Muslim world. By placing calligraphy on everyday items – like clothing or home décor – the book might suggest that such art is a defining characteristic of Muslim culture in Iraq. However, for Muslim readers, this could feel like an oversimplification, as calligraphy is primarily found in religious contexts – emblems and places like wall decorations and mosques – not on every single item in a Muslim household. This approach risks aligning with the Western view of the ‘Orient’ as exotic, mystical, and defined by religious ornamentation, rather than showcasing the complexity and diversity of Muslim life beyond these aesthetic features (Said, 1995).

The fourth book in this analysis, Traveling Man – The Journey of Ibn Battuta 1325-1354, also written and illustrated by James Rumford (2001), presents an interesting contrast to Silent Music and Muhammad (peace be upon him). The book recounts the adventures of the famous Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta, with illustrations that are contained within varied frames on each page. These framed images are complemented by shifting background and margin designs, creating a dynamic visual experience. The use of colour is especially noteworthy – dark tones contrast with lighter margins, which helps to create varying relationships between text and illustration, establishing a sense of weight and balance (Painter et al., 2013, p. 93). Several design features from the Arab world, such as calligraphy, are present in the illustrations, but they are not overdone. Instead, these elements are seamlessly integrated into the visual narrative, complementing rather than dominating the story. Alongside the blocks of text detailing various landmarks and events, there is a thin, curving strip of text running through each page, with Ibn Battuta’s first-person narration. This technique effectively mirrors the style of a travelogue, bringing the reader into the heart of his

journey.

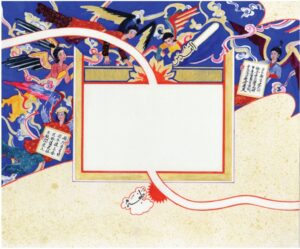

Figure 3. Spread from Traveling Man – The Journey of Ibn Battuta 1325-1354 by James Rumford, © 2001, showing celestial beings. Spread shared by the author/illustrator James Rumford with permission to reprint.

However, one illustration in particular (see Figure 3) draws attention for its depiction of celestial beings. These figures, resembling angels, are illustrated similarly to the way angels were portrayed in Muhammad (peace be upon him) by Demi. Yet in Traveling Man, these beings are holding Chinese script, suggesting that they may not be intended as Muslim angels. This artistic choice aligns more closely with the popular mainstream conception of angels in Western culture, which departs from the Islamic understanding of celestial beings as manifestations of divine light. This depiction echoes the concern I raised in my analysis of Muhammad (peace be upon him), reinforcing the challenge of accurately representing religious figures and symbols in children’s literature.

The next book in my analysis is The Carpet Boy’s Gift by Pegi Deitz Shea and illustrated by Leane Murin (2003). In this book, the images are mostly contained and bound, with the exception of one particularly striking spread. The illustrator skilfully uses varying sizes and focal points to draw the reader’s attention, particularly in moments where characters make direct eye contact. This connection between the characters and the reader is most evident on the final page, a powerful double-page spread that presents an aerial view of a town. In this scene, a group of child workers is depicted marching in open air toward a future of freedom. What makes this page especially poignant is the illustrator’s choice to include two beautiful birds soaring above the children. These birds symbolically represent the freedom the children are heading toward, offering a subtle but hopeful message amidst their struggles.

In terms of the book’s representation of Pakistani society, the illustrations are mostly accurate, with appropriate clothing and facial features for the characters. However, one notable issue arises in the depiction of a busy marketplace. While the scene shows people buying and selling goods and carrying merchandise, the marketplace more closely resembles an Arab marketplace than a Pakistani one. Several men are illustrated wearing Arab jilbaabs and headgear, which, although common in the broader Muslim world, are not typical of Pakistani attire. Additionally, a goat herder walking through the marketplace is shown, which is an unusual depiction in this context. While goat herding is common in Pakistan, it is not typically seen in the middle of a bustling marketplace. This seems to reflect a broader, Westernized misunderstanding that all Muslim cultures are the same or that they share the same cultural practices. The illustrations fail to capture the diversity of cultural practices within different Muslim-majority countries, such as the distinct cultural traits found in Pakistan.

Figure 4. Front cover of The Carpet Boy’s Gift by Pegi Deitz Shea, illus. Leane Morin, © 2003,published by Tilbury House.

Moreover, there is an aspect of the book that undermines the central message about child labour. Although the text critiques the exploitation of children, the images fail to depict the suffering or distress typically associated with such exploitation. On the cover, for example, the protagonist is shown carrying a heavy carpet without any visible discomfort (see Figure 4). While a few images do hint at the agony of the children’s labour, the majority depict them working without hesitation or visible distress, which dilutes the seriousness of the book’s intended message. The images, rather than emphasizing the painful realities of child labour, instead present the children as passive or even somewhat content in their work, thus contradicting the text’s effort to critique this practice. The lack of a more accurate emotional portrayal in the illustrations detracts from the book’s powerful critique of child labour.

The final book in this analysis is Ziba Came on a Boat by Liz Lofthouse, illustrated by Robert Ingpen (2007). This story follows a young Afghan Hazara girl, Ziba, who escapes her war-torn homeland on a boat to Australia. In the early pages, the text recounts her life before the war – how she played with children her age and how her family was happy. However, the illustrations starkly contrast with this sense of joy. Instead, the reader encounters dull, sombre colours, dilapidated buildings, and children in ragged clothes. The girls, regardless of their age, are shown wearing headscarves, even inside their home. When the girls are working in the kitchen, they are depicted performing tasks mechanically, facing away from one another, which emphasizes a sense of isolation and emotional distance. Ziba’s mother is shown as utterly despondent, her face devoid of the peaceful expression described in the text. As the reader continues through the pages, an overwhelming atmosphere of darkness and fear pervades, expressed through the distressed expressions of the characters and the dark, undefined backdrops. Notably, the only instances of direct eye contact in the book come from Ziba and her father – Ziba’s gaze is full of sorrow, seemingly asking for pity, while her father’s stare is sharp and domineering.

Ironically, the only happy faces depicted in the book are those of Western children, whom Ziba envisions in a dream, supposedly welcoming her. However, the illustration fails to convey warmth or compassion; instead, these children appear indifferent to her plight, with expressions that suggest they are unaware or unconcerned with her suffering. In fact, Ziba is positioned at the centre of the image, looking out at the reader with sorrowful eyes, while the children laugh carelessly. If one were to ignore the text, the images might even seem to depict these children mocking her. This stark contrast between the text and the illustrations emphasizes the book’s underlying dissonance – while the narrative seeks to evoke empathy for Ziba, the images seem to undermine this intention, leaving readers with a sense of confusion rather than compassion.

Findings and Discussion

Muslims have long been subject to negative representations and systemic racism, often portrayed in the media as backward, war-torn, oppressed, and deficient. These stereotypical perceptions of Muslims are not only widespread but are also reflected in children’s literature. As picturebooks are powerful visual narratives, the images in these books communicate as strongly, if not more so, than the accompanying text. My analysis of the illustrations in the six picturebooks listed above has revealed both positive depictions and troubling stereotypes about Muslims. The following findings highlight the most significant issues that emerged from this analysis.

1. Muslims are always in war-torn places and are used to hardship

A recurring theme across the books is the depiction of Muslims as living in constant conflict or struggling with difficult conditions. The media often focus on war and refugees, and this narrative has become synonymous with the Muslim world in the Western imagination. In Ziba Came on a Boat, the portrayal of Ziba’s life in Afghanistan, even before the war, is one of devastation, with no indication of peace or prosperity. Similarly, The Carpet Boy’s Gift and Silent Music show children living under harsh, difficult conditions, reinforcing the stereotype that Muslim societies are perennially in crisis. Sami, from My Beautiful Birds, is shown in a refugee camp, while Ali in Silent Music faces life in war-torn Baghdad. These representations contribute to a one-dimensional portrayal of Muslim life, leaving out the diversity of experiences within these communities, and further entrenching the idea that Muslims are constantly victims of violence and upheaval.

2. Muslims are defined by headscarves and jilbaabs

Another issue highlighted by this analysis is the oversimplified portrayal of Muslim identity through the lens of specific cultural symbols, particularly the hijab and jilbaab. In My Beautiful Birds, the depiction of young girls wearing hijabs – sometimes even while playing or at home – misrepresents Islamic practices. In Islamic tradition, the hijab is only obligatory for girls once they reach puberty, yet this portrayal suggests that Muslim girls are expected to wear it from a very young age, even in informal settings. This could lead readers to mistakenly believe that the hijab is a universal practice for all Muslim girls, regardless of age or context.

Similarly, the depiction of men wearing jilbaabs in The Carpet Boy’s Gift – a garment more closely associated with Arab culture than with Islam itself – reinforces the misconception that all Muslims dress in the same way, or that the jilbaab is a religious obligation rather than a cultural one. The book’s portrayal of a Pakistani marketplace, filled with men in Arab-style clothing, presents a homogenized view of the Muslim world, overlooking the cultural diversity within Muslim-majority countries. The reader may come away with the impression that all Muslims are Arabs, further blurring the lines between cultural and religious identity.

3. Insufficient research and oversimplified depictions of Muslim life

One of the most significant issues that emerged from this analysis is the lack of rigorous research in the creation of these books. In Muhammad (peace be upon him) by Demi and Traveling Man: The Journey of Ibn Battuta by James Rumford, the depiction of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and celestial beings (angels) raises important questions. Did these authors/illustrators conduct enough research into Islamic traditions and cultural nuances, or did they rely on popular media portrayals and their own interpretations? The choice to depict the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) as a gold silhouette, while well-intentioned, still falls short of respecting Islamic prohibitions against any visual representation of the Prophet, even in abstract form (Mehmat & May, 2020). Similarly, the portrayal of angels as human-like beings, resembling figures from other religious traditions, undermines the unique theological understandings of Islam.

Such portrayals highlight the importance of extensive research when representing minority groups. The failure to differentiate between cultural symbols (like the jilbaab or the hijab) and religious practices leads to a distorted, simplified view of Muslim life. The misrepresentation of Muslim identity in children’s literature reflects a broader issue in the Western imagination: the inability to see beyond stereotypes and acknowledge the complexities of Muslim cultural contexts.

4. Subtle but harmful stereotyping in children’s literature

The illustrations in these books often reinforce the idea that Muslims are ‘the Other’, reinforcing long-standing stereotypes. For example, the use of muted, earthy colours in the books, such as the brown tones in My Beautiful Birds, Ziba Came on a Boat, and Silent Music, contributes to a sense of despair, foreignness, and otherness. These visual choices, while artistic, can subtly communicate that Muslim life is inherently tragic or disconnected from Western notions of normalcy and happiness. Similarly, the use of Arabic calligraphy as a recurring motif in Silent Music risks reducing Muslim culture to religious ornamentation rather than acknowledging the diversity of Muslim experiences. While the use of calligraphy is beautiful and evocative, its omnipresence may suggest to young readers that Muslim life is defined by religious symbols rather than by the complex and varied lives of Muslim people.

In Ziba Came on a Boat, the portrayal of a happy pre-war life in Afghanistan is contradicted by the illustrations, which show dilapidated buildings and forlorn children. This contradiction highlights how the Western gaze often frames Muslim lives as inherently sad or tragic. The lack of emotional connection or interaction between characters in Ziba Came on a Boat further reinforces a sense of isolation and distance, distancing the reader from the shared humanity of the characters.

Implications for Teaching

Books serve as both mirrors and windows for readers. Serafini (2014) underscores the four dimensions involved in creating and interpreting visual representations: the person interacting with the visual, the designer of the image, the image itself, and the context in which the interaction occurs (p. 36). He notes that creators cannot fully control the meanings viewers derive from their work. Thus, even when care is taken to authentically represent a culture, interpretations may vary. However, it remains essential for authors and illustrators to strive for accuracy and avoid reinforcing harmful stereotypes of the groups they depict.

Short and Fox (2003) emphasize that stories can be ‘accurate but not authentic’ when they portray cultural practices that exist but are not central to the group’s code (p. 380). This notion is especially relevant when analyzing books that represent minoritized groups. For Muslim children and children learning about Muslim cultures, it is crucial that picturebooks serve as genuine, unbiased mirrors and authentic windows. Books should reflect the true diversity, complexity, and vibrancy of these cultures, rather than reducing them to stereotypes. Writers and illustrators must carefully examine the ‘discourses of power’ (p. 382) in their portrayals, consciously resisting the temptation to perpetuate inaccurate or oversimplified narratives that often dominate mainstream media.

Picturebooks play a key role in second or foreign language development, especially when they represent diverse cultural experiences (Astorga, 1999). This makes the authenticity of illustrations in multicultural picturebooks particularly significant in language learning contexts. When students are exposed to visuals that reinforce stereotypes or misrepresent minoritized groups, it complicates their development of both linguistic and intercultural competence. When faced with books that might perpetuate cultural stereotypes, educators can turn these moments into opportunities for critical discussion. Colton et al. (2023) highlight how initial reactions to texts or visuals can be transformed through thoughtful discussion and exploration of alternative interpretations. In language classrooms, such discussions become a springboard for deeper understanding, enabling students to critically reflect on their perceptions of other cultures while simultaneously honing their linguistic abilities.

For language educators, this research emphasizes the importance of carefully evaluating the visual elements in the picturebooks they select for their classrooms. It also underscores the need to cultivate students’ critical visual literacy skills alongside their language proficiency. By incorporating discussions about cultural representation into language lessons, teachers can foster more inclusive and culturally responsive learning environments, where students not only gain language skills but also the tools to engage thoughtfully with the diverse world around them.

Conclusion

The findings of this analysis underscore the subtle yet pervasive nature of racial and cultural stereotyping in children’s literature. While the books analyzed do offer some positive representations of Muslim characters and experiences, they also perpetuate problematic portrayals of Muslims as victims, as monolithic in their cultural practices, and as subjects of endless turmoil. These representations often reflect Western misunderstandings of Islam and Muslim societies. As critical race theory suggests, racism often operates subtly, embedded in everyday representations that seem normal but are, in fact, misrepresentations (Gillborn, 2015). In the case of these picturebooks, the normalization of stereotypes about Muslims not only distorts their image but also reinforces harmful misconceptions.

When it comes to education, particularly in classrooms, this need for accuracy extends to how we engage with these texts. The classroom should become a space for addressing and unpacking the implications of cultural representations. It is not only about providing students with books that avoid negative stereotypes but also about helping students to critically engage with the texts, ensuring they do not internalize misconceptions. Given the importance of children’s books in shaping young minds, it is crucial that authors, illustrators, and publishers engage in thorough research and adopt a more nuanced, culturally sensitive approach when representing minority groups. Efforts must be made to produce literature that counters harmful stereotypes and offers a more accurate, diverse portrayal of Muslim life – one that reflects the complexity, vibrancy, and richness of Muslim cultures, rather than reducing them to a set of simplified, often negative, tropes.

Bibliography

Demi (2003). Muhammad. Margaret K. McElderry Books. Link to the read aloud

Del Rizzo, Suzanne (2017). My Beautiful Birds. Pajama Press. Link to the read aloud

Lofthouse, Liz, illus. Robert Ingpen (2007). Ziba Came on a Boat. Kane/Miller Book Publishers, Inc. Link to the read aloud

Rumford, James (2001). Traveling Man: The Journey of Ibn Battuta, 1325-1354. Houghton Mifflin. Link to the read aloud

Rumford, James (2008). Silent Music: A Story of Baghdad. Roaring Brook Press. Link to the read aloud

Shea, Pegi Deitz, illus. Leane Morin, (2003). The Carpet Boy’s Gift. Tilbury House Publishers. Link to the read aloud

References

Agosto, D. E. (1999). One and inseparable: Interdependent storytelling in picture storybooks. Children’s Literature in Education, 30(4), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022471922077

Albalawi, M. (2015). Arabs’ stereotypes revisited: The need for a literary solution. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 6(2), 200–211. https://journals.aiac.org.au/index.php/alls/article/view/1414

Anderson, N. A. (2002). Elementary children’s literature: The basics for teachers and parents. Allyn & Bacon.

Astorga, M. C. (1999). The text-image interaction and second language learning. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 22(3), 212–233. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ594651

Aziz, S. (2012). The Muslima within American children’s literature female identity and subjectivity in novels about Pakistani-Muslim characters. In J. Stephen (Ed.), Subjectivity in Asian children’s literature and film: Global theories and implications (pp. 43–58). Routledge.

Aziz, S. (2019). Immigrant memoirs as reflections of time and place: Middle Eastern conflict in graphic novels. In H. Johnson, J. Mathis, & K. G. Short (Eds.), Critical content analysis of visual images in books for young people: Reading images (pp. 208–226). Routledge.

Bang, H. K., & Reece, B. B. (2003). Minorities in children’s television commercials: New, improved, and stereotyped. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 37(1), 42–67.

Barthes, R. (1977). Introduction to the structural analysis of narratives. In R. Barthes (Ed.), Image, Music, Text (pp. 32-51). HarperCollins UK.

Bell, D. (1992). Faces at the bottom of the well: The permanence of racism. Basic Books.

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix–xi.

Broadway, F. S., & Conkle, D. M. (2010). The power of illustrations in multicultural picture books: Unfolding visual literacy. In L. A. Smolen, & R. A. Oswald (Eds.), Multicultural literature and response: Affirming diverse voices (pp. 67-94). Bloomsbury.

Colton, J., Serafini, F., Lovett, T., Forrest, S., Gale, J., Gehling, K., Shin, A., & Carter, J. (2023). Readers matter: Seven transactions with the visual, linguistic and material elements in a picture book. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 46(3), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-023-00050-6

Crisp, T., & Hiller, B. (2011). ‘Is this a boy or a girl?’: Rethinking sex-role representation in Caldecott medal-winning picture books, 1938–2011. Children’s Literature in Education, 42(3), 196–212.

Delgado, S., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York University Press.

Gillborn, D. (2015). Intersectionality, critical race theory, and the primacy of racism. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414557827.

Gultekin, M., & May, L. (2020). Children’s literature as fun-house mirrors, blind spots, and curtains. The Reading Teacher, 73(5), 627–635.

Hughes, C. (2012). Seeing blindness in children’s picture books. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 6(1), 35–51.

Kérchy, A. (2014). Picture books challenging sexual politics. Pro-porn feminist comics and the case of Melinda Gebbie and Alan Moore‘s ‘Lost Girls’. Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies, 20(2), 121–142.

Koltz, J., & Kersten‐Parrish, S. (2020). Using children’s picture books to facilitate restorative justice discussion. The Reading Teacher, 73(5), 637–645.

Lambert, M. D. (2015). Reading picture books with children: How to shake up storytime and get kids talking about what they see. Charlesbridge.

Latham, S. (2016). The global rise of Islamophobia: Whose side is social work on? Social Alternatives, 35(4), 80–84.

Ledesma, M. C., & Calderón, D. (2015). Critical race theory in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414557825

Liou, D. D., & Cutler, K. D. (2020). Disrupting the educational racial contract of Islamophobia: Racialized curricular expectations of Muslims in children’s literature. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 24(2), 1–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1753680

Manglik, G., & Siddique, S. (2018). Muslims in story: Expanding multicultural understanding through children’s and young adult literature. ALA Editions.

Manolessou, K., & Salisbury, M. (2012). Being there: The role of place in children’s picturebooks. Journal of Writing in Creative Practice, 4(3), 367–399.

Mastracci, D. (2016, February 29). ‘NY Times portrays Islam more negatively than cancer, major study finds: Overwhelming proof points to an institutional bigotry.’ AlterNet. http://www.alternet.org/grayzone-project/ny-times-portrays-islam-more-negatively-cancer-major-study-finds

Meunier, C. (2017). The cartographic eye in children’s picture books: Between maps and narratives. Children’s Literature in Education, 48(1), 21–38.

Mills, K. A., & Unsworth, L. (2018). The multimodal construction of race: A review of critical race theory research. Language and Education, 32(4), 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1434787

Montag, J. L., Jones, M. N., & Smith, L. B. (2015). The words children hear: Picture books and the statistics for language learning. Psychological Science, 26(9), 1489–1496.

Mullins, M. (2016). Counter-counterstorytelling: Rereading critical race theory in Percival Everett’s Assumption. Callaloo, 39(2), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1353/cal.2016.0070

Newstreet, C., Sarker, A., & Shearer, R. (2019). Teaching empathy: Exploring multiple perspectives to address Islamophobia through children’s literature. The Reading Teacher, 72(5), 559–568.

Painter, C., Martin, J. R., & Unsworth, L. (2013) Reading visual narratives: Image analysis of children’s picture books. Equinox Publishing.

Panjwani, A. A. (2020). Perspectives on inclusive education: Need for Muslim children’s literature. Religions, 11(9), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090450

Pérez, H. L., & Solorzano, D. G. (2015). Visualizing everyday racism: Critical race theory, visual microaggressions, and the historical image of Mexican banditry. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 223–238.

Raina, S. (2009). Critical content analysis of postcolonial texts: Representations of Muslims within children’s and adolescent literature [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Arizona.

Richards, J. C., & Anderson, N. A. (2003). What do I see? What do I think? What do I wonder? (STW): A visual literacy strategy to help emergent readers focus on storybook illustrations. The Reading Teacher, 56(5), 442–444. https://aquila.usm.edu/fac_pubs/4475/

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1982). The literary transaction: Evocation and response. Theory into Practice, 21, 268–277.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In R. B. Ruddell, M. R. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (pp. 1057–1092). International Reading Association.

Said, E. W. (1995). Orientalism. Penguin Books India.

Salisbury, M., & Styles, M. (2020). Children’s picture books: The art of visual storytelling. Laurence King Publishing.

Schmidt, C. (2006). Not just Disney: Destructive stereotypes of Arabs in children’s literature. In D.A Zabel (Ed.), Arabs in the Americas: Interdisciplinary essays on the Arab diaspora (pp. 169–182). Peter Lang.

Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the visual: An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. Teachers College Press.

Short, K. G. (2016). Critical content analysis as a research methodology. In H. Johnson, J. Mathis, & K. G. Short (Eds.), Critical content analysis of children’s and young adult literature: Reframing perspective (pp. 1–15). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315651927

Short, K. G., & Fox, D. L. (2004). The complexity of cultural authenticity: A critical review. National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53, 373–384.

Sims, R. (1982). Shadow and substance: Afro-American experience in contemporary children’s

fiction. National Council of Teachers of English.

Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2001) Critical race and LatCrit theory and method: Counter-storytelling. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 14(4), 471–495.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390110063365

Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800103

Spoonley, P. (2019). Racism and stereotypes. In S. Ratuva (Ed), The Palgrave Handbook of ethnicity (pp. 483–498). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2898-5_36

Stockton, R. (1994) Ethnic archetypes and the Arab image. In E. N. McCarus (Ed.), The development of Arab-American identity (pp. 119–153). University of Michigan Press.

Torres, H. J. (2016). On the margins: The depiction of Muslims in young children’s picture books. Children’s Literature in Education, 47(3), 191–208.

Wiseman, A. M. (2013). Summer’s end and sad goodbyes: Children’s picture books about death and dying. Children’s Literature in Education, 44(1), 1–14.

Wiseman, A. M., Vehabovic, N., & Jones, J. S. (2019). Intersections of race and bullying in children’s literature: Transitions, racism, and counternarratives. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(4), 465–474.

Vandergrift, K. E. (1980). Child and story: The literary connection. Neal-Schuman Publishers.