| Legally Scripted Fictions: Fathers and Fatherhood in English Language Picturebooks with Children from Refugee Backgrounds

Ekaterina Strekalova-Hughes, Nora Peterman and Kylee Lewman |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Drawing from a critical multicultural analytic lens and methods of critical content analysis, this study examines representations of fathers and fatherhood in 43 fictional picturebooks featuring children from refugee backgrounds. We investigate thematic and ideological significances in how fathers are represented and towards what purposes, attending in particular to embedded assumptions regarding who enacts power and agency. The analysis reveals stories that reinforce legally scripted fictions, connecting refugee fatherhood to legal procedures for claiming asylum, resettlement policies, and institutionally assumed needs, at the expense of multifaceted cultural and interpersonal aspects of fatherhood. These picturebooks often foreground the loss or separation of fathers due to vague status-related reasons (for example, ‘war’), occurring on a centralized ‘refugee timeline’ that primarily serves to establish the protagonist’s ‘reasonable fear’, as required for asylum. When fathers are present, stories foreground their economic hardship and responsibility, echoing discourses of need circulated by funding-dependent agencies and institutions working with refugees. We offer counternarratives to support English language teaching and argue that fathers and fatherhood must be understood as multilayered and diverse, moving beyond bureaucratic discourses towards culturally dynamic depictions.

Keywords: refugee discourses, fathers/fatherhood, picturebooks, critical content analysis, children’s literature

Ekaterina Strekalova-Hughes (PhD) is an Assistant Professor of Early Childhood Education/Urban Teacher Preparation at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Her research agenda revolves around educational experiences of children and families from refugee backgrounds and culturally sustaining pedagogies. [end of page 10]

Nora Peterman (PhD) is an Assistant Professor of Language and Literacy at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Her research concentrations include children’s and young adult literatures, digital literacies, and the cultural, political, and intergenerational dimensions of youth literacy and language learning.

Kylee Lewman is an undergraduate alum. of University of Missouri-Kansas City. She is currently volunteering in the Peace Corps before coming back for her graduate studies.

Introduction

‘And one day the war took my father’ (Sanna, 2016, unpaginated)

In recent years, escalating global refugee crises have contributed to increasing student diversity in schools. The term refugee officially refers to a person who,

owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country. (UN General Assembly, 1951, p. 152) [end of page 11]

Half of the world’s refugees are young children (UNHCR, 2018) who may enter English language classrooms in their resettling countries with a wide range of educational experiences and expectations. The diverse languages, cultures and histories within and across populations seeking refuge present unique challenges and exciting opportunities for English language teachers, who increasingly recognize the value of teaching English using authentic children’s literature representative of their diverse young learners (Mourão, 2009, 2015, 2016; Vasquez, 2017) and of sharing picturebooks about children and families from refugee backgrounds in their classrooms (Arizpe, Colomer & Martínez-Roldán, 2014; Hope, 2014; Morgado, 2018). Such stories serve multiple purposes. As a format, picturebooks offer rich visual images that interact with written text, a multimodal storytelling design that is especially beneficial for literacy and language development in ELT contexts (see Alter, 2018; Arizpe, Bagelman, Devlin, Farrell & McAdam, 2014; Bland, 2015; Guadamillas Gomez, 2015; Louie & Sierschynski, 2015). Picturebooks about children with refugee experiences offer the added potential to shape and affirm identities of learners from various refugee backgrounds and depict positive possibilities for their future(s). This literature also functions as a window into lived experiences of children who identify as refugees for their peers, inviting content and language integrated learning (Morgado, 2018) that promotes critical global literacies (Yoon, Yol, Haag & Simpson 2018) and social action (Bishop, 1990).

At the same time, it is important that English language educators critically evaluate children’s literature in order to avoid teaching texts as politically and culturally neutral, which may inadvertently reinforce damaging or negative stereotypes about young learners and their families who have sought refuge. Drawing from a critical multicultural analytic lens (Botelho & Rudman, 2009) and methods of critical content analysis (Johnson, Mathis & Short, 2016), this study examines depictions of fathers and fatherhood in 43 fictional picturebooks featuring children from refugee backgrounds as main characters. We investigate thematic and ideological significances (Stephens, 1992) in how fathers are represented and towards what purposes, attending in particular to embedded assumptions regarding who enacts power and agency, and underscoring institutional framings of identities related to asylum claim procedures (UNHCR, 1979) and resettlement policies (Zetter, 1991). We conclude with implications for English language teachers. [end of page 12]

Representation in Children’s Literature

Representation of fathers in children’s literature is important for child identity development (Adams, Walker & O’Connell, 2011). For example, stories that render fathers invisible in children’s everyday lives, as sharing less emotion and physical contact with children than mothers, and/or as being uninvolved in domestic activities may reinscribe ‘obstacles to egalitarian parenthood’ and constrain children’s gendered identities (Adams, Walker & O’Connell, 2011, p. 267). When texts are uncritically presented, children may learn that socially constructed messages about gendered roles in stories reflect wider social norms that they are expected to embody (Vasquez, 2017).

Children’s literature also mediates English language teachers’ beliefs, who draw on their perceptions of fathering styles and father involvement in interactions with learners and families from refugee backgrounds (Nzinga-Johnson, Baker & Aupperlee, 2009). These beliefs and assumptions about people from refugee backgrounds, including fathers, are influenced by heightened politicized discourses that need careful unpacking to help teachers build strong family partnerships, which is a key goal of education development and delivery.

Existing scholarship in children’s literature provides valuable insights into representations of fathers that might be useful. It has been found, for example, that children’s literature is generally prone to imbalance in parental representations, with fathers being less visible than mothers (Adams, Walker & O’Connell, 2011; Anderson & Hamilton, 2005). At the same time, intersections of fatherhood with refugee status adds complex cultural and legal layers of representation that warrant specific examination. Research on children’s literature about refugee children is emerging in the field (see Dolan, 2014; Dudek, 2018; Hope; 2008, 2015, 2016; Nel, 2018; Savsar, 2018), examining narrative constructions of identity(ies), memory and conflict across texts and contexts. We draw across these significant bodies of knowledge to investigate how representations of fathers and fatherhood intersect with the legal/institutional understandings of refugees in picturebooks for young children.

Cultural Underpinnings of Refugee Fatherhood

We also approach this research with an understanding that ‘fatherhood, history reminds us, is a cultural invention’ (Demos, 1982, p. 444). Fatherhood, as with any gendered family [end of page 13] role, is socioculturally situated. Research provides insights into cultural variations in fathering across cultures, countries, and times (Shwalb, Shwalb & Lamb, 2013). At the same time, ‘a monolithic and simplistic understanding of fathering in diverse cultures that does not include knowledge of contextual influences can result in stereotyping and overgeneralization’ (Miller & Maiter, 2008, p. 280). This stipulation is especially relevant for fathers that cross cultural borders and social contexts, including refugees. Changing cultural paradigms mid-fatherhood (and mid-motherhood), for example moving to Canada or Israel, has inspired parents to sustain valuable components of parenting from their home nations (for example, Ethiopia) as well as to integrate new elements of parenting beliefs from the new context (Roer‐Strier, Strier, Este, Shimoni & Clark, 2005).

To build powerful family partnerships, English language teachers must navigate complex, evolving cultural aspects of fatherhood with their diverse learners from refugee backgrounds as well as majority-culture language learners. These efforts involve high levels of educational diplomacy and benefit from specific cultural and contextual insights. Children’s literature featuring children and fathers from refugee backgrounds can serve as a valuable resource for teachers (Bishop, 1990). Accordingly, this research explores representations of fathers from refugee backgrounds to better equip teachers in understanding how legal refugee status intersects with the narrative of cultural and interpersonal beliefs and practices of fatherhood.

We also note that critically evaluating this literature is a complex endeavor, as ‘a work’s propagation of prejudice can be both subtle and overt. Art is often ideologically ambivalent, humanizing in some ways and dehumanizing in others’ (Nel, 2018, p. 359). That is to say, there is no perfect story – our focus on representations of refugee fatherhood is intended to deepen understanding of these texts and support English language teachers in critically distinguishing such elements.

Theoretical Framework

This study draws from critical multicultural perspectives that situate children’s literature as historical and cultural artifacts and that represent and reproduce social organization and hierarchies of power (Botelho & Rudman, 2009). We understand that children’s literature is never neutral, but rather ideologically-framed and designed to shape readers’ beliefs and emotions (Stephens, 1992). Literature written for children reflects the authors’ perceptions, [end of page 14] beliefs, and sociopolitical histories, and therefore risks reinscribing discourses about marginalized social and cultural groups that are positioned outside of dominant norms (Botelho & Rudman, 2009). Framed by intersectional feminist scholarship (Collins, 2002; Crenshaw, 1989; Crenshaw, 1991), our analytic lens puts at the forefront the ‘varied histories within a society and acknowledges the dynamic and fluid nature of cultural experiences within unequal access to social power experienced by some groups within a society’ (Johnson & Gasiewicz, 2017, p. 29). Accordingly, our work seeks to recognize and examine how the refugee label is connected to multiple and overlapping identities of fatherhood, and the ways in which these are positioned and shaped by structures of oppression.

Our study is also in conversation with Refugee Critical Race Theory, or RefugeeCrit (Strekalova-Hughes, Bakar, Nash & Erdemir, 2018). RefugeeCrit extends from and expands critical race theory in education (for example, Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995; Ladson-Billings, 2013), underscoring connections of refugee-specific legal and economic mechanisms of oppression to dominant generative discourses impacting education of young children. First, we closely consider the tenet of RefugeeCrit that stipulates that imperialism, colonialism, and racism are endemic to society, contribute to refugee flight, and reveal themselves in legal and economic mechanisms that influence life experiences of children and families from refugee backgrounds. These endemic forces also shape unifying narratives, or ‘single stories’ (Adichie, 2009), about refugees as connected to legal procedures for claiming asylum and resettlement policies that emphasize their institutional identity (Strekalova-Hughes, 2019). RefugeeCrit forefronts agentive refugee voices, invites counternarratives, and exposes the mismatch between purposes for which refugees tell their stories and purposes for which others share and use them. Second, we rely on the tenet of intersectionality in which refugee status, a layer of identity and experience, uniquely unfolds within racialized cultural contexts and shifting societal mechanisms of power and oppression.

The above lenses frame our investigation of literary father representations that are statused by their protective legal designation as refugees and gendered in response to different cultural contexts as families move across political, linguistic, cultural, and social lines. In combination, these theoretical frameworks allow English language teachers to [end of page 15] critically examine how sociopolitical and historicized relations of power are embedded in children’s texts (Botelho & Rudman, 2009), thus supporting critical literacy engagement in their classrooms and examining the ways in which depictions of family roles and refugee fatherhood in picturebooks may reflect and construct unifying legal and policy discourses surrounding the refugee label.

Methodology

Since early childhood, readers engage with picturebooks more frequently than other types of texts (Braden & Rodriguez, 2016). This study analyzes English-language narrative picturebooks that feature first-generation refugee children as main characters, written for young children (birth through eight years) and depicting or addressing conflicts that occurred after World War II. We identified texts by searching relevant online catalogues and booklists published by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), Publishers Weekly, Colorín Colorado, The Vancouver Public Library, The New York Times, National Public Radio, Booklist, Amazon and other online booksellers, and a range of other websites and blogs targeting educators and parents. We included stories that used the words ‘refugee’, ‘asylum’, ‘asylum seeker’, and ‘displaced’ or ‘displacement’ in the title, book description, or within the text, as well as searching texts that were often categorized more broadly as stories about immigration or migration but that referred to circumstances of forced displacement and seeking refuge. In this way, the diverse experiences of people rather than their officially sought or granted status drove our text selection.

We were also mindful that although our research focuses on English-language picturebooks, a majority of children and families who experience forced displacement seek protection in countries where English is not the primary language (UNHCR, 2019). We chose to focus on children’s literature in English as this language has been used as a dominant vehicle for shaping much of the global discourse on forced displacement, and stories in this language are increasingly utilized as an educational resource in English Language Education. While our text set includes stories of seeking asylum in various countries, most of these narratives depict children’s subsequent resettlement in predominantly English-speaking countries, and were primarily published in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Our initial review identified a corpus of 65 books that fit these selection criteria. We then narrowed our sample to focus on 43 [end of page 16] picturebooks that mentioned protagonists’ fathers in order to maintain congruency with our research questions (see Bibliography).

Data Analysis

Methods of critical multicultural analysis (Botelho & Rudman, 2009) and critical content analysis in children’s literature (Johnson, Mathis & Short, 2017) guided our research. We adhered to an inductive analytic process in iterative phases. Applying selected theoretical tenets, we independently carried out close readings across and within texts, noticing themes and categories that were later deliberated for shared team insights. While much of the salient data was discursively established in the written text of the narratives, our analysis interrogated textual and visual representations and word/image interactions (Arizpe & Styles, 2003; Sipe, 1998; Wolfenbarger & Sipe, 2007). Drawing from RefugeeCrit as our analytic lens for thinking ‘within, through, and beyond the text’ (Short, 2017, p. 4), we critically interrogated how legal and economic tenets interplay with representations of fathers/fatherhood in stories for young children. Our analysis also attended to where and with whom power and agency is located when representing ‘those who fall outside the U.S. dominant norms’ (Johnson & Gasiewicz, 2017, p. 30), and considered how the picture book images ‘expand and enhance ideological statements of the words’ (Nikolajeva, 2010, p. 169). Following Short’s (2017) guidelines for critical content analysis in children’s literature, our unit of analysis was fathers’ actions, thoughts, and interactions in the stories as well as any other characters’ actions, thoughts, and interactions related to fathers. We also paid close attention to the critical incidents within stories that intersect with the UNHCR’s (2011) legal definition of a refugee, such as evincing a well-founded fear related to war/violence/persecution, fleeing home, and seeking protection of another state.

Findings

The purpose of this study was to investigate how agency and power is embedded in representations of refugee fathers and fatherhood, and to examine the assumptions these create in picturebooks featuring young refugee protagonists. We wanted to see how cultural and interpersonal intricacies of fatherhood are represented when families from refugee backgrounds cross cultural contexts. Instead, our major findings revealed [end of page 17] overwhelming discursive connections between fathers and their institutional refugee label, creating legally-scripted fictions of refugee fatherhood. These legally-scripted fictions emerged through the following themes:

- The centrality of lost fathers;

- Fathers as catalyzing figures in refugee flight;

- Refugee fatherhood characterized by economic struggle.

1. Lost Fathers

The most prevalent theme in representing refugee fathers is their separation from young protagonists. This separation aligns with a centralized refugee timeline that occurs due to status-related causes. Lost fathers are explicitly missed, grieved, remembered or forgotten by the protagonist. These representations tie narratives about refugee fathers to a dominant discourse informed largely by the legal procedures for claiming asylum, rather than cultural and personal aspects of fathering.

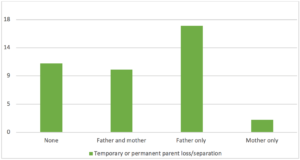

Timeline of loss. Stories where protagonists lost or were temporarily separated from both parents, fathers, or mothers were found across the data (see Figure 1). The rarest form of separation is from a mother alone, as only one text depicts a father and son moving to a new country and applying for asylum for the mother who stayed behind. The most frequent form of separation is from fathers alone.

Figure 1: Stories with temporary or permanent parent loss/separation

Moreover, our analysis reveals a clear timeline of father presence and loss in children’s lives that closely relates to their refugee status. The main characters often start in their [end of page 18] country of origin with both parents in their life. Then, as families are forced to flee their home, young protagonists become permanently or temporarily separated from their fathers. As the stories describe children’s lives upon resettlement in new countries, fewer fathers than mothers reunite with their families. Take, for example, The Silver Path (Harris & Ong, 1993), in which the protagonist recalls his smiling father building a doghouse for their new puppy pre-conflict. As the mother and the child spend their days in a refugee camp, they think back to the time when the father was taken to a prison camp and desperately hope to reunite someday. Barring a single exception (Meltem’s Journey, Robinson, Young, & Allan, 2010), the texts do not depict experiences of loss or separation once families resettle. This separation timeline suggests that the loss of a father is unique to refugee experiences and nurtures an assumption that fathers’ lives are endangered by refugee turmoil, but are unconditionally safe once they reach their new country.

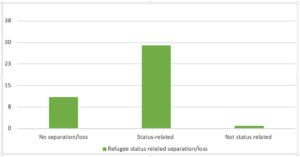

Status-related causes of loss. Temporary or permanent loss of fathers is only attributed to reasons commonly associated with legal refugee status (see Figure 2). More specifically, fathers overwhelmingly often die or leave to fight in a war, are imprisoned, or separated from their families during transition to safety. For example, in Dia’s Story Cloth (Cha, Cha & Cha, 1996, unpaginated), the protagonist’s father is taken to fight in a war: ‘My father was sent to fight in Xieng Khouang province. He never came back’. In The Roses in my Carpet (Khan & Himler, 2004, unpaginated), the father is an accidental war victim, ‘I will hold my head high for the sake of my father [farmer] who died ploughing our field in the war’.

Figure 2: Stories with refugee status-related separation/loss [end of page 19]

These incidents of separation often present fathers as helpless, diminishing their individual power and agency. Illustrations depicting fathers with hands forcefully held behind their backs, heads down, occur across multiple texts (for example, in Navid’s Story (Glynne & Topf, 2015) and The Silver Path (Harris & Ong, 1993).

While wars/conflicts were a predominant cause of separation, the historical and political context of the conflicts and fathers’ motives for participation are mostly unstated. In such instances, fathers are rendered as subjects who lost their families and/or lives for unknown or vague reasons (for example, war) with no explanation. These losses primarily illustrate sacrifice and trauma associated with the institutional refugee label. For example, the narrator of My Name is Sangoel (Williams, Mohammed & Stock, 2009) states, ‘Sangoel’s father was killed in the War in Sudan’ and moves on with the story. This death serves as a narrative device framing Sangoel’s refugee storyline, establishing his legal status and the basis of the ‘reasonable fear’ this requires (UNHCR, 2011).

A notable exception to this trend is found in Gleam and Glow (Bunting, 2005). This story provides readers with a positive, agentive framing of one father’s participation in war, emphasizing from the father’s perspective the honour in his commitment to defend his country: ‘…this is our country. I will fight with the Liberation Army to stop them [invaders] from pushing us out of our own land’. Once the child protagonist learns the rationale for his father’s decision to fight in the war, it becomes his source of pride: ‘“My father is in the underground”, I told him [a peer], and I felt proud’. After fleeing to a neighboring country, Victor hopes to reunite with his father yet feels connected with him through the legacy of his cause, ‘We were allowed to paint the initials of the Liberation Army on a wall and we felt good, as if we were fighting alongside the liberators to set our country free’.

Remembered/forgotten fathers. Our analysis reveals that fathers often narratively vanish from a story after their loss/separation establishes the refugee status of the protagonist. After their separation, child characters may sometimes briefly think about, miss, or remember their father. While the loss of a parent is a very difficult event to address in literature for young children, ignoring this loss diminishes the full humanity and lived experiences of children with refugee histories. Moreover, it may also reinscribe othering discourses about inexorable violence in protagonists’ home countries. For [end of page 20] instance, in Hamid’s Story (Glynne & Senior, 2014), Hamid resettles with his mother but learns that his father died back home. Hamid is described grieving, being upset and losing his appetite. His mother talks to him about his grief, and Hamid walks away thinking:

I shouldn’t be so upset because, in the end, the reason why we left Eritrea was because it was so dangerous. I began to feel much better after our chat. I realized that it was a good thing we had left Eritrea and come to this new country. (Glynne & Senior, 2014, unpaginated)

In this way, the story utilizes his father’s passing to demonstrate the inherent danger of Hamid’s flight-worthy home country, while simultaneously rendering his grief and trauma less valid.

In contrast, exceptions to this pattern highlight the powerful connection between children and their fathers. In Waiting for Papa (Lainez & Accardo, 2004), protagonist Beto takes active steps to bring his father to their new country (writing letters, speaking on the radio) and continues to remember his father in very special ways while awaiting reconciliation (designing a Father’s Day T-shirt, fundraising with peers to buy a special gift for Papa). We also found examples of remembering lost fathers that highlight the role of fathers beyond their refugee status. Some characters remember their fathers as powerful linkages to culture and heritage. In A Song for Cambodia (Lord & Arihara, 2008), Arn remembers his father explaining how Cambodian music exists in memories and is passed down from generation to generation. In My Name is Sangoel (Williams, Mohammed & Stock, 2009), Sangoel holds on to his name after resettlement, against the pressures of assimilation, because it was the ‘name of my father and my grandfather and his father before him’. Other protagonists remember their fathers for their words of wisdom and courage, for example, Brothers in Hope (Williams & Christie, 2007), The Banana Leaf Ball (Milway & Evans, 2017), and The Treasure Box (Wild & Blackwood, 2017).

2. Fathers as Catalyzing Figures in Refugee Flight

The centrality of fathers’ legal refugee status continues in depictions of fathers as the catalyzing figures in refugee flight and troublemakers instigating families’ need to flee as a result of their opinions/beliefs and actions. [end of page 21]

Fathers as decision makers. The stories position fathers as key decision makers in moments of increasing danger at home and as citizens whose opinions/actions oppose those in power. Fathers make decisions about when it is time to flee, where to flee to, what belongings to take, and how to secure asylum. A representative example comes from Azzi’s father in Azzi in Between (Garland, 2011, unpaginated):

‘Quick! Get in the car! No time to lose, no time to pack. We must leave the country. We must leave the country. We are in terrible danger!’ At that moment, Azzi’s life changed forever.

Similar episodes are present in The Colour of Home (Hoffman & Littlewood, 1992, unpaginated), when the father finds his son hiding from soldiers, ‘My father came in and fetched me out from under the bed and said we were leaving’. Similarly, the father’s voice proclaiming the need to flee was echoed in How Many Days to America? (Bunting & Peck, 1988, unpaginated), ‘When they [soldiers] were gone my father said, “We must leave right now”’. Moreover, fathers are positioned as central decision makers in determining where to travel, such as in Gervalie’s Journey (Robinson, Young & Allan, 2008, unpaginated), ‘So Dad and I decided that we should escape to Europe’ or in Petar’s Song (Mitchel & Binch, 2003, unpaginated), ‘Get ready, all of you. Go West’. Finally, fathers determine what belongings to take at departure. For example, in The Banana Leaf Ball (Milway & Evans, 2017), the father tells the son to leave his soccer ball behind.

Fathers also play an essential role in resettlement negotiations. For example, in Hamzat’s Journey (Robinson, Young & Allan, 2009a, unpaginated), the father applies for asylum for his wife and the rest of the family. They joke, ‘Mum says Dad applied for the rest of the family to come because he doesn’t like cooking!’ In Meltem’s Journey (Robinson, Young & Allan, 2010), the father negotiates paperwork in multiple countries fighting for his family’s legal right to stay. Although mothers are present in scenes of negotiations with immigration officials, fathers are depicted handling the paperwork and are addressed, while mothers are simply present: ‘A woman came next to me and asked me and Dad a lot of questions’ (Robinson et al., 2010). The only exception in such representation of parents occurs when the father is already lost/separated. Then, mothers have to make critical decisions about flight, and negotiate legal aspects of crossing borders. [end of page 22]

Fathers as troublemakers. Fathers also catalyze flight due to opinions/beliefs or personal actions that endanger their family and dictate the need to leave home. For example, in both The Little Refugee (Do, Do & Whatley, 2011) and Dia’s Story Cloth (Cha et al., 1996), fathers are described as fighting on the ‘wrong’ side of the conflict, which later put the entire family at risk of retribution. Dia describes the actions they took to protect their lives, ‘My mother had destroyed all the documents we had relating to my father and the war’ (Cha et al., 1996). After the conflict in Laos, her deceased father’s alliance with Americans placed his family in danger of persecution and eventually caused them to flee their home.

Fathers’ beliefs and actions are consistently described as having a clear cause and effect relationship with the need to flee. For example, in Navid’s Story (Glynne & Torf, 2015, unpaginated), the protagonist remembers, ‘the reason that we left Iran was that my dad disagreed with the Government and how things were going’. In The Silver Path (Harris & Ong, 1993), the child explains, ‘Papa told them [soldiers] they should pay for what they took, like other people. That is why he is in prison camp now and why I have been sent with mama to this hotel for refugees’. In Mohammed’s Journey (Robinson, Young et al., 2009b), the main character recalls, ‘My dad, along with many other Kurds, was secretly working for a group in opposition to Saddam […] That’s why in 1994, when Mum was pregnant with me, the soldiers came for the first time’. Only one text, Rachel’s Story (Glynne & Maldonado, 2014, unpaginated) connected a mother’s beliefs/actions to the need to flee, ‘I didn’t go to school because my mum practiced a different religion from most of the people’. Being harassed by police and local people for her beliefs, ‘She felt like she really wanted to escape’. In general, mothers do not appear to have beliefs or political opinions, which may inadvertently reinforce colonial and imperialist paradigms that fail to recognize the nuanced complexities of human agency in diverse cultural contexts (Hoodfar, 1992; Mahmood, 2011).

While texts readily cite fathers’ beliefs/actions as the reason for the persecution of the family, again these beliefs and actions are not well described. For example, in Gervalie’s Journey (Robinson et al., 2008), ‘Some men came to his house looking for Dad… Even speaking to Dad on the phone was difficult and dangerous for Mum’. The natural question of why men wanted to prosecute her father remains unanswered. In [end of page 23] Hamid’s Story (Glynne & Senior, 2014, unpaginated), the protagonist recalls, ‘My dad knew some secrets about the Eritrean government. The officials said that if he told anyone these secrets, they would kill my mum and me! So dad told us we had to run away’. Much like the stories that depicted loss/separation of fathers, the conditions underlying these events are not unpacked, nor is the government critiqued for wrongdoing or unjust actions (such as corruption, violation of human rights, etc.). Since sharing someone’s secrets is generally perceived negatively, this may lead readers to assume that the father is in the wrong or should not be trusted with secrets. Without providing adequate explanation, the narrative fails to validate the father’s beliefs and actions as worthy and just, despite the danger this may pose to his family.

3. Refugee Fathers Experiencing Need and Economic Struggles

Finally, our analysis reveals hegemonic interconnections between fathering/fatherhood, refugee status, and socioeconomic challenges and responsibility. Fathers are portrayed with presumably low-skill jobs before and after resettlement and as struggling to provide basic needs for their families. Prior to resettlement, the majority of the fathers are described as farmers, including David’s Journey (Jal, Jacobs & Bezesky, 2012), Dia’s Story Cloth (Cha et al., 1996), The Banana Leaf Ball (Milway & Evans, 2017), and The Silence in the Mountains (Rosenberg & Soentpiet, 1999). Farming at times represents hardship for the protagonists, such as the son in The Roses in My Carpets (Khan & Himler, 2004), who describes his deceased father’s occupation: ‘My father was a farmer. At the mercy of weather or anyone who would steal his land and crops’. The son seems to look down at his father’s occupation as lacking agency and instead plans to make a living with skills that no one can take away from him (weaving carpets).

Throughout the journey to resettlement, these stories continue to depict fathers’ ongoing struggle and failure to provide food and shelter for their families. In Meltem’s Journey (Robinson et al., 2010), the protagonist recalls:

Dad couldn’t work while they sorted out our asylum application. The three of us lived in one room in a hostel. We shared a kitchen with about ten people. I remember it as dirty and there being lots of noisy dogs around. [end of page 24]

These depictions of fathers primarily reflect institutionalized narratives about refugee experiences that is largely driven by resettlement aid organizations (Strekalova-Hughes, Bakar, Nash & Erdemir, 2018; Zetter, 1991; Zetter, 2007). Narratives of privation are often highlighted to increase fundraising (Kisiara, 2015) and essentialize seeking refuge to an identity of struggle and need.

Out of our 43 texts, there were five clear exceptions: a father as driver (Mohammed’s Journey, Robinson et al., 2009b and Home & Away, Marsden & Ottley, 2008), as doctor (Azzi in Between, Garland, 2012), as engineer (Hamzat’s Journey, Robinson et al., 2009a) and as travel agent (Gervalie’s Journey, Robinson et al., 2008), as well as a few stories with unclear occupations. These stories subsequently highlight the economic downgrade and struggle associated with refugee discourses. For example, in Hamzat’s Journey, ‘Dad was an engineer before all the trouble, but then there was no work. Sometimes he did building repair work, but that’s all’ (Robinson et al., 2009a). In The Boy and the Wall (Bishara & Aida Refugee Camp, 2005, unpaginated), a protagonist wondered if the wall ‘would stop his dreams just as it stopped his father from going to work’. In Azzi in Between, Azzi’s father was a doctor, but considers farming while looking for a job in the new country: ‘If I had a garden, at least I could plant my beans and grow our food’ (Garland, 2012). When he finally finds work, he is illustrated as putting on large work boots unlike his medical scrubs from back home. Moreover, the major challenges faced by Azzi’s family end as soon as their legal challenges are resolved and Azzi’s father is able to secure work papers. This speedy economic recovery towards self-sufficiency is a major resettlement policy goal, and it is perhaps unsurprising to find this discourse embedded in picturebook stories as well. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the same policy that results in below-skill hiring and lower wages in the long-term is featured as a happy ending for young readers, despite the economic and cultural challenges that persist, especially for resettled refugee fathers.

While food and shelter are important, a more holistic understanding of fatherhood is represented in a The Treasure Box (Wild & Blackwood, 2017). This story features a father who strives to pass on his people’s culture and heritage to his child. The center of the narrative is the importance of valuing one’s culture and heritage over the size of a dinner plate or tidiness of a temporary shelter. Yet such nuances are rarely depicted in the [end of page 25] focal texts. Perhaps, influenced by the widespread misunderstanding of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Strekalova, 2016) that largely shapes discourse around post-resettlement services (Lonn & Dantzler, 2017), it is difficult for authors to imagine that experiences of extreme hardship and danger, including food and housing insecurity, does not necessarily prevent fathers from striving for higher ideals and goals. For example, the fight to pass on language and culture and desire for peace and prosperity back home can occur at the same time as economic struggle. What stories choose to feature provides valuable insights into how generative discourses shaped by mechanisms of economic access reproduce deficit framing of refugee fatherhood.

Discussion

Fatherhood is a cultural and gendered construction subject to existing and shifting societal dynamics. As children seeking refuge transition between and across geopolitical locations (for example, from a home country to a country of resettlement), their understanding of family norms across cultural boundaries may evolve. While no two stories among those analysed for this study offered identical representations of fathers and fatherhood, our findings suggest some problematic trends in children’s picturebooks about refugee experiences. It is troubling that most texts represent separation or loss of a father in solely status-related terms, referring to a generic war or government opposition without providing more nuanced explanations of the conditions leading to these separations. Such stories establish fathers’ institutional refugee identity, illustrating a protagonist’s eligibility for protective refugee status in accordance with the UNHCR. However, without clearly addressing underlying causes and conditions that led to fathers’ actions and families’ plights, these narrative devices risk dehumanizing individuals by framing fathers as passive or even careless victims, rather than as principled actors making risky but ethical decisions in the face of oppression and injustice. Individuals with firsthand experiences of seeking refuge offer powerful counternarratives to these depictions, including fathers who feel deep attachment to their home countries and who are proud of their resistance to injustice in their homeland. For example, a South Sudanese father corrected Strekalova-Hughes’s reference to ‘Sudan’ in her field notes, stating: ‘It’s South Sudan, not Sudan. We fought for that name at a high cost’ (Strekalova-Hughes & Wang, 2019). [end of page 26]

Moreover, stories that address conflicts in superficial terms risk alienating or othering the young readers and families with firsthand experiences seeking refuge with whom teachers hope to engage and connect. Loss and separation from fathers must be understood in terms greater than as a ‘refugee tax’ establishing a surviving protagonist’s qualifying criteria for asylum (UNHCR, 1979), as this creates a misleading assumption of fathers’ insignificance in children’s lives. As such, narratives in which lost fathers are authentically missed, grieved, and remembered (for wisdom, bravery, culture and heritage, or special relational moments) are more representative of the fathers’ role in early childhood.

The timeline of loss or separation from fathers in these stories implicitly establishes a binary between safety and security in resettlement narratives. Nearly every picturebook we analyzed separated fathers from their children before arriving in a new country. This representation suggests that resettlement countries are ‘the answer and the arrival place that promises safety and salvation for the world’ (Johnson & Gasiewicz, 2017, p. 41). However this utopian ideal does not capture new inequities experienced by children and families upon resettlement, including experiences of racism and discrimination based on nationality, religion and language status. Safety and security challenges may persist in the communities where refugees are resettled, as reflected in a CBS News headline: ‘After escaping war in their homeland, some Syrian refugees are afraid of getting shot in their new home […] in North St. Louis’ (CBS St. Louis, 2016).

The primary exception to this idealistic framing in resettlement is in depictions of fathers’ economic need and struggle. This framing reflects public and popular discourse, influenced by fundraising aims of resettlement aid organizations (Kisiara, 2015; Zetter, 1991), that emphasize the institutionally-determined needs and bureaucratic identities of fathers from refugee backgrounds. Yet when actually asked, these fathers often understand their role as providing cultural and moral guidance, not only food and shelter. For example, a Karen father from a refugee background shared his efforts to actively work against ‘children losing our language and culture in America’ (Strekalova-Hughes & Wang, 2019) and consciously making time for home storytelling in Karen within a busy work schedule and economic realities. To represent such voices, children’s literature must provide more [end of page 27]counternarratives valuing the role of fathers (and parents) beyond their economic responsibilities and contributions.

Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

Our analysis of picturebooks about children from refugee backgrounds revealed that these stories represent fathers and fatherhood through legally-scripted fictions overwhelmingly tied to protagonists’ legal refugee status. We argue that these limited literary representations have tangible consequences for young English language learners and their teachers. Chimamanda Adichie (2009) famously cautioned against the danger of the single story, arguing that ‘the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.’ Separation and loss is an undeniable element of refugee flight, yet this does not reflect the entirety of the experience or reflect the full humanity of individuals who experience forced displacement and seek refuge. In contrast, rich cultural representations of fatherhood in children’s literature may support English language learners’ efforts to resist assimilations (Arizpe, Bagelman, Devlin, Farrell & McAdam, 2014) and positively affect their identity development as family members (Koffi, 2011). It may further shape English language teachers’ perception of fathers, influencing their work with learners from refugee backgrounds as well as their instructional approach to related content and literature in their classrooms.

English language teachers can resist legally-scripted fictions by intentionally seeking out narratives of refugee representations that reflect the complexity of these human experiences and addressing fathers’ aspirations that involve cultural sustainability and moral fulfillment. They can further add to this representational diversity by inviting and sharing stories that highlight the generosity of fathers from refugee backgrounds as a fundamental cultural value common across resettling communities, and exploring stories of economically and otherwise successful fathers from refugee backgrounds after their resettlement.

Since there is no such thing as a perfect text, English language teachers must further counter problematic discourses in picturebooks by inviting their students to question stereotypical or superficial depictions and to interrogate the whys and hows in [end of page 28] representations of fathers/fatherhood. For instance, when reading stories that emphasize fathers’ opinions or actions as catalyzing family flight, English language teachers and students can research, discuss, and write in response to the origin and consequences of particular conflicts, collectively unpacking picturebook words and illustrations as meaningful representations with historical, political, and cultural significance. Although loss and separation are traumatic, understanding the context of fathers’ sacrifices may build readers’ respect and admiration for the resilience of refugee families, rather than implicitly soliciting pity or even condescension. This work develops students’ multicultural perspectives and facilitates authentic, meaningful instructional connections between local English language classrooms and critical global issues.

Children’s literature has the potential to affirm young readers’ identities or to reinforce stereotypes and bigotry. Strong stories will acknowledge the precarities of displacement while nourishing what Philip Nel (2018) terms an empathic imagination, which ‘brings people of all ages closer to understanding the displacement felt by migrants, refugees, and those in diasporic communities […] It tells these children, “You are heard.”’ (p. 358). As such, fathers and fatherhood in picturebooks about refugees must be read and understood as multilayered and diverse, not legally scripted, moving beyond prevalent refugee discourses informed by the legal procedures for claiming asylum and resettlement aid and towards the cultural and personal aspects of fathering.

Bibliography

Beckwith, K. (2005). Playing War. L. Lyon (Illus.). Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House Publishers.

Bishara, A. A. & Aida Refugee Camp. (2005). The Boy and the Wall. L. al-Azzeh, M. Qassim, A. Malash, M. Sarhaan, L. al-Azzeh, K. Qarqi, D. Musallam, O. Khador, H. Musallam, B. Zubun (Illus.). Bethlehem, Palestine: Lajee Center.

Bunting, E. (1988). How Many Days to America? B. Peck (Illus.). New York: Clarion Books.

Bunting, E. (2001). Gleam and Glow. P. Sylvada (Illus.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt Children’s Books.

Cha, D. (1996). Dia’s Story Cloth. C. Cha & N. T. Cha (Illus.). New York: Lee & Low. [end of page 29]

Charara, H. (2004). The Three Lucys. S. Kahn (Illus.). New York: Lee & Low.

Davies, N. (2018). The Day War Came. R. Cobb (Illus.). Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Del Rizzo, S. (2017). My Beautiful Birds. Toronto, Ontario: Pajama Press.

Do, A. & Do, S. (2011). The Little Refugee. B. Whatley (Illus.). Sydney, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Garay, L. (1997). The Long Road. Toronto, Ontario: Tundra Books.

Garland, S. (2012) Azzi in Between. London, England: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

George, A. M. (2017). Out. Swan (Illus). Toronto, CA: Scholastic Canada.

Glynne, A. (2014). Ali’s Story. S. Maldonado (Illus.). London, England: Wayland.

Glynne, A. (2014). Hamid’s Story. T. Senior (Illus.). London, England: Wayland.

Glynne, A. (2014). Rachel’s Story. S. Maldonado (Illus.). London, England: Wayland.

Glynne, A. (2015). Navid’s Story. J. Topf (Illus.). London, England: Wayland.

Goring, R. (2017). Adriana’s Angels. E. Meza (Illus.). Minneapolis, MN: Sparkhouse Family.

Harris, C. (1993). The Silver Path. H. Ong (Illus.). Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press.

Hoffman, M. (1992). The Colour of Home. K. Littlewood (Illus.). London, England: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Jal, D. W. & Jacobs, L. K. (2012). David’s Journey. T. Bezesky (Illus.). Sioux Falls, SD: The Khor Wakow School Project.

Khan, R. (2004). The Roses in My Carpets. R. Himler (Illus.). Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry & Whiteside.

Knight, M. B. (2018). Who Belongs Here? A. S. O’Brien (Illus.). Thomaston, ME: Tilbury House Publishers.

Lainez, R. C. (2004). Waiting for Papa. A. Accardo (Illus.). Houston, TX: Piñata Books.

Landowne, Y. (2010). Mali Under the Night Sky. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos Press.

Lofthouse, L. (2007). Ziba Came on a Boat. R. Ingpen (Illus.). La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller Book Publishers.

Lord, M. (2008). A Song for Cambodia. S. Arihara (Illus.). New York: Lee & Low.

Marsden, J. (2013). Home and Away. M. Ottley (Illus.). Sydney, Australia: Lothian Children’s Books. [end of page 30]

Milway, K. S. (2017). The Banana Leaf Ball: How Play Can Change the World. S. W. Evans (Illus.). Toronto, Ontario: Kids Can Press Ltd.

Mitchell, P. (2003). Petar’s Song. C. Binch (Illus.). London, England: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Park, F. & Park, G. (1998). My Freedom Trip: A Child’s Escape from North Korea. D. R. Jenkins (Illus.). Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press.

Robinson, A. & Young, A. (2008). Gervelie’s Journey: A Refugee Diary. J. Allan (Illus.). London, England: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Robinson, A. & Young, A. (2009a). Hamzat’s Journey: A Refugee Diary. J. Allan (Illus.). London, England: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Robinson, A. & Young, A. (2009b). Mohammed’s Journey: A Refugee Diary. J. Allan (Illus.). London, England: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Robinson, A. & Young, A. (2010). Meltem’s Journey: A Refugee Diary. J. Allan (Illus.). London, England: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Rosenberg, L. (1999). The Silence in the Mountains. C. K. Soentpiet (Illus.). New York: Orchard Books.

Ruurs, M. (2016). Stepping Stones: A Refugee Family’s Journey. Z. A. Badr (Illus.). Custer, WA: Orca Book Publishers.

Sanna, F. (2016). The Journey. London, England: Flying Eye Books.

Shea, P. D. (1995). The Whispering Cloth: A Refugee’s Story. A. Riggio (Illus.). Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press.

Smith, I. (2010). Half Spoon of Rice. S. Nhem (Illus.). Manhattan Beach, CA: East West Discovery Press.

Wild, M. (2017). The Treasure Box. F. Blackwood (Illus.). Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Williams, K. L. & Mohammed, K. (2007). Four Feet, Two Sandals. D. Chayka (Illus.).Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Books for Young Readers.

Williams, K. L. & Mohammed, K. (2009). My Name is Sangoel. C. Stock (Illus.). Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdman’s Books for Young Readers.

Williams, M. (2007). Brothers in Hope: The Story of the Lost Boys of Sudan. R. G. Christie (Illus.). New York: Lee & Low. [end of page 31]

References

Adams, M., Walker, C. & O’Connell, P. (2011). Invisible or involved fathers? A content analysis of representations of parenting in young children’s picturebooks in the UK. Sex Roles, 65 (3-4), 259-270.

Adichie, C. (2009). The danger of a single story. TEDGlobal. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_ofN_a_single_story.html

Alter, G. (2018). Integrating postcolonial culture(s) into primary English language teaching. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 6 (1), 22-44.

Anderson, D. A. & Hamilton, M. (2005). Gender role stereotyping of parents in children’s picturebooks: The invisible father. Sex Roles, 52 (3-4), 145-151.

Arizpe, E., Colomer, T. & Martínez-Roldán, C. (2014). Visual Journeys Through Wordless Narratives: An International Inquiry with Immigrant Children and the Arrival. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Arizpe, E., Bagelman, C., Devlin, A. M., Farrell & McAdam, J. E. (2014). Visualizing intercultural literacy: Engaging critically with diversity and migration in the classroom through an image-based approach. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14 (3), 304-321.

Arizpe, E., & Styles, M. (2003). Children Reading Pictures: Interpreting Visual Texts. London: Routledge/Falmer.

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6 (3), ix-xi.

Bland, J. (2015). Pictures, images, and deep reading. Children’s Literature in Language Education Journal, 3 (2), 24-36.

Botelho, M. J. & Rudman, M. K. (2009). Critical Multicultural Analysis of Children’s Literature: Mirrors, Windows, and Doors. New York: Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (2002). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43 (6), 1241-1299.

Crenshaw, K. (2018). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989]. In K. [end of page 32] Bartlett & R. Kennedy (Eds.), Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender. New York: Routledge, pp. 57-80.

Demos, J. (1982). The changing faces of fatherhood: A new exploration in American family history. In S. Cath, A. Gurwitt & J. M. Ross (Eds.), Father and Child: Developmental and Clinical Perspectives. Boston: Little, Brown, pp. 425-445.

Dolan, A. (2014). Intercultural education, picturebooks and refugees: Approaches for language teachers. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2 (1), 92-109.

Dudek, D. (2018). Seeing the human face: Refugee and asylum seeker narratives and an ethics of care in recent Australian picture books. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 43 (4), 363-376.

Guadamillas Gómez, M. V. (2015). Supporting literacy in English as a second language: The role of picturebooks. Revista Docencia e Investigación, (25.1), 91-105.

Hoodfar, H. (1992). The veil in their minds and on our heads: The persistence of colonial images of Muslim women. Resources for Feminist Research, 22 (3/4), 5.

Hope, J. (2008). ‘One day we had to run’: The development of the refugee identity in children’s literature and its function in education. Children’s Literature in Education,39 (4), 295-304.

Hope, J. (2015). ‘A well-founded fear’: Children’s literature about refugees and its role in the primary classroom (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Department of Educational Studies Goldsmiths, University of London.

Hope, J. (2016). “The soldiers came to the house”: Young children’s responses to The Colour of Home. Children’s Literature in Education, 49 (3), 302-322.

Johnson, H. & Gasiewicz, B. (2017). Examining displaced youth and immigrant status through critical multicultural analysis. In H. Johnson, J. Mathis & K. G. Short (Eds.), Critical Content Analysis of Children’s and Young Adult Literature: Reframing Perspective. New York: Routledge, pp. 28-43.

Johnson, H., Mathis, J. & Short, K. G. (Eds.). (2017). Critical Content Analysis of Children’s and Young Adult Literature: Reframing Perspective. New York: Routledge.

Kisiara, O. (2015). Marginalized at the centre: How public narratives of suffering perpetuate perceptions of refugees’ helplessness and dependency. Migration Letters, 12 (2), 162. [end of page 33]

Koffi, L. R. (2011). Adolescents’ Perceptions of Fathering Factors that Influence Identity Development. Denton: Texas Woman’s University.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2013). Critical race theory—What it is not!. In M. Lynn & A. D. Dixson (Eds.), Handbook of Critical Race Theory in Education. London: Routledge, pp. 54-67.

Ladson-Billings, G. & Tate, W. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97 (1), 47-68.

Lonn, M. R. & Dantzler, J. M. (2017). A practical approach to counseling refugees: Applying Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Journal of Counselor Practice, 8 (2), 61-82.

Louie, B. & Sierschynski, J. (2015). Enhancing English learners’ language development using wordless picture books. The Reading Teacher, 69 (1), 103-111.

Mahmood, S. (2011). Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Miller, W. & Maiter, S. (2008). Fatherhood and culture: Moving beyond stereotypical understandings. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 17 (3), 279-300.

Morgado, M. (2018). Minority cultures in your school: A CLIL approach. Children’s Literature in Language Education Journal, 6 (2), 28-45.

Mourão, S. J. (2016). Picturebooks in the primary EFL classroom. Children’s Literature in Language Education Journal, 3 (2), 25-43.

Mourão, S. J. (2009). Using stories in the primary classroom. BritLit: Using literature in EFL classrooms, 17-26.

Mourão, S. (2015). The potential of picturebooks with young learners. In J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 Year Olds. London: Bloomsbury.

Nel, P. (2018). Introduction: Migration, refugees, and diaspora in children’s literature. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 43 (4), 357-362.

Nikolajeva, M. (2010). Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers. New York: Routledge.

Nzinga-Johnson, S., Baker, J. A. & Aupperlee, J. (2009). Teacher-parent relationships and school involvement among racially and educationally diverse parents of kindergartners. The Elementary School Journal, 110 (1), 81-91. [end of page 34]

Roer‐Strier, D., Strier, R., Este, D., Shimoni, R. & Clark, D. (2005). Fatherhood and immigration: Challenging the deficit theory. Child & Family Social Work, 10 (4), 315-329.

Savsar, L. (2018). “Mother tells me to forget”: Nostalgic re-presentations, re-membering, and re-telling the child migrant’s identity and agency in children’s literature. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 43 (4), 395-411.

Short, K. G. (2017). Critical content analysis as a research methodology. In H. Johnson, J. Mathis & K. G. Short (Eds.), Critical Content Analysis of Children’s and Young Adult Literature. New York: Routledge, pp. 1-15.

Sipe, L. R. (1998). How picturebooks work: A semiotically framed theory of text-picture relationships. Children’s Literature in Education, 29 (2), 97-108.

Shwalb, D. W., Shwalb, B. J. & Lamb, M. E. (Eds.). (2013). Fathers in Cultural Context. London:Routledge.

Stephens, J. (1992). Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction. Boston: Addison-Wesley Longman Limited.

Strekalova, A. S. (2016). The mythology of the Maslow’s pyramid. Marketing in Russia and Abroad, 6, 3-14.

Strekalova-Hughes, E., Bakar, A. Nash K. & Erdemir, E. (2018, April). Refugee critical race theory in education: An emerging ontological and epistemological lens. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Education Research Association, New York, NY.

Strekalova-Hughes, E. (2019). Unpacking refugee flight: Critical content analysis of picturebooks featuring refugee protagonists. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 21 (2), 23-44.

Strekalova-Hughes, E. S. & Wang, X. C. (2019). Perspectives of children from refugee backgrounds on their family storytelling as a culturally sustaining practice. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 33 (1), 6-21.

UN General Assembly (1951). Convention relating to the status of refugees. United Nations, Treaty Series, 189, 138-220. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org [end of page 35]

UNHCR (1979). Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/4d93528a9.pdf

UNHCR (2011). The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/about-us/background/4ec262df9/1951-convention-relating-status-refugees-its-1967-protocol.html

UNHCR (2018). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2017/

Vasquez, V. M. (2017). Critical Literacy across the K-6 Curriculum. New York: Routledge.

Wolfenbarger, C. D. & Sipe, L. (2007). A unique visual and literary art form: Recent research on picturebooks. Language Arts, 84 (3) 273-280.

Yoon, B., Yol, Ö., Haag, C. & Simpson, A. (2018). Critical global literacies: A new instructional framework in the global era. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62 (2), 205-214.

Zetter, R. (1991). Labelling refugees: Forming and transforming a bureaucratic identity. Journal of Refugee Studies, 4 (1), 39-62.

Zetter, R. (2007). More labels, fewer refugees: Remaking the refugee label in an era of globalization. Journal of Refugee Studies, 20 (2), 172-192. [end of page 36]