| Picturebooks as Vehicles: Creating Materials for Pedagogical Action

David Valente and Sandie Mourão |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Picturebooks have long been positioned as vehicles to support teachers and their learners to explore compelling and challenging themes in early English language education and more recently to support the development of intercultural and citizenship education. This article reports on the materials development phase of a professional development course which formed part of an Erasmus+ project. Its main goal was to enable teacher-participants to confidently plan for, manage and assess intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early ELT and to successfully co-create a set of pedagogical materials. Based on a reflective practice approach, we highlight how the professional development course incorporated the applied science, craft and reflective model over two course iterations to support a collaborative picturebook-based materials writing process. An evaluation of the draft materials was undertaken to assess the strengths and weaknesses of teaching and learning sequences for intercultural awareness and citizenship, and to inform and shape two subsequent course iterations. We conclude this paper with reflections on how we addressed certain challenges that we encountered to support teacher-participants to craft materials around picturebooks for intercultural citizenship education.

Keywords: picturebooks, intercultural citizenship education, materials writing, professional development, early English language teaching

David Valente is a PhD research fellow in English language and literature subject pedagogy at Nord University, Norway. He has over 20 years’ experience in ELT as a teacher, teacher educator, academic manager, author and editor. His PhD project researches the significance of picturebooks for in-depth intercultural citizenship learning within English subject pedagogy.

Sandie Mourão (PhD) is a full-time research fellow at CETAPS/FCSH, Nova University Lisbon with over 30 years’ experience in the field of early English language education as a classroom teacher, teacher educator and consultant. She is presently researching intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks, with additional interests in pre-primary language education, classroom-based assessment and teacher education.

Introduction

In this article, we share a series of reflections which have emerged from our participation in an Erasmus+ project, and one of its main activities, a professional development course for teachers of English, teacher librarians and student teachers working with children aged between five and twelve years old. Intercultural Citizenship Education through Picturebooks in Early English Language Learning (ICEPELL) ran between 2019-2022 and comprised a consortium of five European partner countries (Germany, Italy, Norway, Portugal and the Netherlands). The partners, of which we were members, included researchers, teacher educators and materials writers who shared a common interest in the theory and practice of picturebooks in early English language learning settings. One of ICEPELL’s main activities was a teacher development programme, the ‘ICEPro course’. A key outcome of the ICEPro course was the co-creation of a set of pedagogical materials based on a picturebook for developing intercultural citizenship education, an ‘ICEKit’, which embodied Jane Spiro’s (2022) application of ‘the big idea’ to ELT materials creation. She asserts, ‘The big idea must do many things: it must work well beyond your own classroom, it must be supported by research, it must fill a perceived gap’ (p. 479). Our reflections untangle the usefulness of ‘the big idea’, that is, of teacher co-created materials for intercultural citizenship education in early language learning with picturebooks. In so doing, we explore the relationship between theory, the designed materials and practice. Our reflections on the materials creation phase of the ICEPro course may offer insights for other teacher education contexts whose aim is to design principled teaching and learning sequences for ICE through picturebooks.

Theoretical Foundations

Intercultural citizenship education in early English teaching

Contemporary citizenship education is integrated into many European education systems in the twenty-first century to develop competences related to ‘effective and constructive interaction with others, thinking critically, acting in a socially responsible manner and acting democratically’ (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2017, p. 9). For example, Norway’s core curriculum states that,

pupils shall develop an understanding of the relationship between individual rights and obligations. Individuals have the right to participate in political activities, while society is dependent on citizens exercising their rights to participate in politics and influence developments in the civil society. The school shall stimulate the pupils to become active citizens. (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2019, p. 9, English-language version)

Democratic citizenship education includes the promotion and protection of human rights, democracy and the rule of law (Council of Europe, 2018). It begins in early childhood education and encompasses a coherent vision through compulsory schooling and into further and higher education. Effective approaches to citizenship education are characterized by classroom-based and real-world experiences that extend into the community, and thereby children could be empowered to act as democratic citizens in the present and the future (Guilherme, 2012; Short, 2011; Vasquez et. al, 2019). Learning another language such as English in the compulsory school years has several benefits for democratic citizenship education (Byram, 2008; Doyé, 1999). These include the facilitation of learners’ communication to negotiate fluid and ever-expanding cultural boundaries, to develop respect, tolerance and empathy, as well as the ability to cooperate with others as flexible, open-minded and critical intercultural thinkers (Bland, 2022; Vasquez et. al, 2019). We have found the Council of Europe’s (2018) Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC) particularly useful for the incorporation of citizenship in teacher education, due to its valuable coverage of competences for English learners to raise their intercultural awareness and participate in society as engaged citizens at local, national and global levels. And as Martyn Barrett and Irina Golubeva (2022, p. 74) suggest, ‘… some of these competences, such as openness and empathy may be targeted from a relatively early age at pre-school and primary school’. We agree that along with criticality, such competences can also be fostered in the English subject to encourage children to express thoughts and feelings through age-relevant tasks and activities – if they are sufficiently equipped with English as well as their other languages.

Initially conceived and subsequently refined by Michael Byram in his seminal work (1997; 2021), and rooted in language teacher education, intercultural citizenship can be characterized as ‘the close relationship between intercultural and democratic competence when acting in real-world situations in which cultural diversity is salient’ (Barrett & Golubeva, 2022, p. 76). Significantly, the RFCDC emphasizes the important role language plays in the implementation of intercultural citizenship education (ICE), which further highlights how English at school is a suitable subject to engage children in intercultural explorations and to spark their civic engagement (Bland, 2022, p. 27). The Norwegian curriculum refers to the importance of English for ‘communicating with others around the world’ and yet a major lacuna still exists. As Barrett and Golubeva (2022) point out, this relates to insufficiently systematic focus on children’s ‘active citizenship competences that are required to take action at the transnational level … with action orientation itself then becoming an important facet of civic-mindedness’ (p. 78). We thus advocate the integration of tasks and activities which scaffold children’s action taking outside of the classroom and help them to transcend their national contexts. For this to become a reality, we envision a departure from a strictly linguistic way of being and doing in English language teaching. We further contend that the relative newness of citizenship-as-content in mainstream ELT school settings, despite policy and curricular aspirations, is due to a lack of support from teacher education and a dearth of age-relevant pedagogical materials for doing citizenship.

Literary texts have long been positioned as vehicles for otherness in the language classroom by ‘taking readers on voyages of discovery or simply by making them look afresh at their everyday surroundings’ (Pulverness, 2014, p. 430; see also Bredella & Delanoy, 1996; Matos, 2012; Morgado, 2018; Volkmann, 2015). Nevertheless, to enable English teachers to skilfully use literary texts as vehicles for ICE, extensive professional development is required, as Janice Bland (2022, p. 70) maintains, ‘teachers need in-depth guidance in extending their own literary competence, their own visual literary, critical literacy and response to multimodal texts’. The importance of a focus on critical visual literacy from the earliest school years is supported by Risager (2022, p. 119). She further argues that the link between interculturality and language learning can be ‘transformative’ when explored in a professional development context by teachers who create materials around verbal and visual texts. Likewise, Spiro (2022, p. 479) concurs that ‘materials are powerful agents of change’, particularly when teachers become ‘co-creators’ and collaborate with their peers, mentored by experienced materials writers. For us, ‘change’ is conceived pedagogically to support teachers to widen the scope of their English lessons. And we posit that transformation can be realized through the co-creation and use of ELT materials based on literature for ICE.

Picturebooks as vehicles for ICE

According to Bland (2022, p. 76), ‘Picturebooks provide complex opportunities for discovery and interpretation of meanings [resulting from] the combinations of pictures, verbal text, typographic creativity, layout and overall design’. Therefore, the characteristics of this literary format augur well for children learning English to explore cultural diversity and make personalized responses to characters, narratives and themes. Furthermore, as Morgado (2019, p. 165) explains, well-selected picturebook titles can function as ‘representations of global diversity and local human action which resonates globally’. With Morgado, we consider careful selection will help students embrace the intercultural domain hand in hand with the citizenship emphasis on civic action.

Recent teacher education projects and school-based research studies have also positioned picturebooks as a vehicle in language and/or other subjects in mainstream education for either interculturality or citizenship education. For example, Morgado (2019) reports on the outcomes of an Erasmus+ project, Identity and Diversity Picture Book Collections which included picturebooks in all of the languages of the European Union. The project’s goals were to enable children to explore intercultural themes such as migration and inclusion through picturebooks and make creative connections to the protagonists. Research in Norway by Heggernes (2019) implemented an intervention study based on a hybrid picturebook-graphic novel in secondary English lessons. Framed by intercultural communicative competence, Heggernes’s findings indicated the development of learners’ cultural awareness and empathy. In particular, her dialogic approach to images offered useful insights regarding learners’ perspective shifts towards an intercultural orientation. A doctoral study by Lopes (2020) in Portugal drew on Byram’s intercultural citizenship model to investigate how three picturebooks were explored for a transformative, global citizenship pedagogy with a class of ‘hard to reach’ (p. 104) 13- to 15-year-olds. Carvalho (2020), also in Portugal, undertook an action research project which involved two picturebooks in her primary class of 9- and 10-year-olds. She selected a picturebook with an explicit citizenship theme and another which required careful mediation for the citizenship themes to emerge. The findings highlighted her role as teacher-mediator for citizenship to be an integral part of her English lessons.

To further clarify the concept of ‘mediation’ and picturebook read-alouds, Ellis and Mourão (2021) explain that it ‘is dependent upon the teacher using a combination of competences effectively to plan and manage an inclusive and effective read-aloud experience where the children interact in a language rich environment and share their personal responses to the picturebook’ (p. 23). Some picturebook research exists which explores aspects of read-aloud mediation in English language education contexts (see e.g., Bortoluzzi et al., 2021; Masoni, 2019; Mourão, 2016; Ellis & Mourão, 2022). But there remains a scant focus in ELT on how teachers can help children to make text-to-life and life-to-text connections to picturebooks (Sipe, 2008), specifically to develop their intercultural competence and to inspire them to take action beyond their classroom walls.

The ICEPro course aimed to contribute to the above lacuna through the systematic incorporation of both interculturality and citizenship through the picturebook-as-vehicle. The main course outcome was to enable teacher-participants to co-create and to experiment with ICE-themed materials in their English lessons. In the next section, we provide a profile of each ICEPro course iteration and we particularly shine a light on how the design of the materials creation phase of the course was approached by the teacher educators.

Picturebook Mediation and Materials Creation in the ICEPro Course

For Ellis and Mourão (2021), the process of picturebook mediation necessarily commences with the selection of a suitable title aligned with explicit pedagogical goals (in this case, children’s intercultural and citizenship education). Selection was therefore prioritised during the ICEPro course supported through collaborative work on a guide developed for this purpose. Materials co-creation was undertaken by the teacher-participants in a similarly experiential and dialogic manner. The teacher educators’ planning of the materials phase of the course was inspired by an adaptation of Wallace’s (1991) tripartite model for a reflective approach to teacher development. Our aim in what follows is to unveil the structure and rationales behind the ICEPro course design and in turn, to potentially offer some insights for teacher education elsewhere.

The ICEPro course

The ICEPro course consisted of a 25-hour input component followed by a mentor-supported, classroom implementation component over a period of three to four months. A total of 61 teacher-participants based in the five partner countries took part in the two course iterations. Collectively, the ICEKits were trialled with approximately 600 children in state schools in Italy, Norway and Portugal. Once the teacher-participants had trialled the ICEKits, they reflected on their classroom practice and made further revisions to these materials. As East (2022) argues,

for teacher education to have any opportunity to be successful in enhancing the implementation of innovation, it needs to hold two tensions in balance: what theory and research say about the benefits of the innovation in question, and what real classroom encounters raise about its challenges. (p. 14, emphasis in original)

The ICEPro courses were originally planned as Erasmus+ mobility activities with travel between the five different partner countries. But, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the iterations of the ICEPro course were adapted and became first virtual and then hybrid in format.

ICEPro Virtual. The initial iteration of the ICEPro course in March 2021 was delivered fully online and involved twenty-four teacher-participants organised as six groups, formed of mixed-nationality, pre- and in-service teachers. The input hours were facilitated by two teacher educators over a three-week period and largely comprised asynchronous tasks on a Moodle platform. Several picturebook read-alouds were recorded by the teacher educators to model effective mediation with response tasks. The teacher-participants interacted on Moodle via Wikis and forums and responded with written comments and oral Loom recordings to explore ICE and discover and select picturebooks by viewing recordings in silent page-turn mode. Each week, the teacher educators co-facilitated a live session on Zoom to reinforce and extend key concepts related to picturebooks for ICE, which included some opportunities for collaboration in breakout rooms.

To begin the ICEKit co-creation process, teacher-participants shared book preferences based on the ‘Picturebook Selection Guide’, agreed on a picturebook and shared possible task and activity ideas through forum posts. Then they embarked on the ICEKit drafting process through the eTwinning platform and were supported by one of six teacher-educator-mentors. Finally, the in-service teacher-participants from each group trialled their ICEKit in the classroom, then reflected on the strengths and weaknesses to modify their materials accordingly. The six ICEKits underwent final content and copy editing by the teacher educator team, and were professionally designed and published online in December 2021.

ICEPro Hybrid. In November 2021, teacher education programmes had resumed physically in each partner country, but transnational mobility remained restricted. In response to this, the teacher educators crafted hybrid content for 40 participants, organized as nine mixed-nationality groups of teacher-participants, again each supported by a mentor. This iteration was delivered intensively in blended mode over five consecutive days. ICEPro Hybrid thus included face-to-face workshops in national groups, focused on the theory and practice of picturebooks for ICE as well as live picturebook read-alouds given by the teacher educators and teacher-participants. They also browsed the 45 picturebooks displayed in each venue. Twelve teacher educators in their respective contexts facilitated the workshops and followed identical facilitators’ notes, presentations and templates for the tasks and activities. Parallel timetables were also planned to establish a shared understanding of core concepts as well as to foster readiness for the co-creation of materials sessions, undertaken collaboratively on Zoom.

The materials co-creation sessions were facilitated by nine mentors, with opportunities for the groups to engage in highly participant-driven collaborative work. This included exchange of ideas for picturebook selection and agreement on a single picturebook title suitable for the teacher-participants’ (present and future) classes, then drafts of ideas for each part of the ICEKit. Like ICEPro Virtual, after the input hours, materials co-creation continued on eTwinning, supported by mentor meetings during classroom trialling by the in-service participants, reflection, evaluation, and final content and copy editing. Then, the nine additional ICEKits were professionally designed and published online in June 2022.

The picturebook selection guide

Given the vast range of English-language picturebooks available and the complexity inherent in cultural diversity, selection of suitable titles presents a challenge for teachers and student teachers who may not be wholly confident with the integration of literature or ICE in early English education. For example, the baseline data from the ICEPELL project needs analysis indicated that teachers were confident about the concepts of intercultural learning and citizenship, yet their shared examples of classroom practice signalled a misunderstanding on a pragmatic level (see also Brunsmeier, 2017, for similar results). Therefore, to support the teacher-participants with this endeavour, the teacher educators developed a comprehensive ‘Picturebook Selection Guide’ (Ibrahim et al., 2022). Underpinned by scholarly and practical work in picturebooks (e.g., Dolan, 2014; Ellis & Brewster, 2014; Leland et al., 2013; Roche, 2015) and intercultural and citizenship education (e.g., Byram, 2008; Council of Europe, 2018; European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2017; Fitzgerald, 2007; Porto, 2016; Rader, 2018), a working group devised picturebook selection criteria organized as three ICE-related focal fields:

- Socially responsible behaviour – interaction with others

- Socially responsible behaviour – interaction with local and global issues

- Sense of belonging and knowing about or responding to own, other and/or heritage cultures

When this selection tool was piloted by the ICEPELL Consortium, a list of 90 picturebooks was collated, and an ICE-continuum became evident in terms of the intercultural and/or citizenship potential these books have for the early English classroom. Some of the titles lend themselves to the development of an intercultural orientation, which corresponds to focal field 3, for example, Hey You! by Dapo Adeola (2021). Others lend themselves to a citizenship-focus, aligned with focal field 2, for example, The President of the Jungle by André Rodrigues, Larissa Ribeiro, Paula Desgualdo and Pedro Markun (2020). A third category provides an opportunity to fuse the intercultural and citizenship domains in ICE. This corresponds to focal field 1 or a blend of all three fields, for example, The Day War Came by Nicola Davies and Rebecca Cobb (2018).

The tripartite model for materials creation

The ICEPro course capitalized on our previous teacher education experiences where the creation of pedagogical materials was also a main objective. We therefore adopted Michael Wallace’s (1991) model of applied science, craft, and reflective frameworks for teacher education, and in this case, like Hughes (2022), with a specific focus on materials writing. First, the applied science model introduced the teacher-participants to key theoretical concepts related to intercultural and citizenship education and picturebooks and aimed to help experientially connect the domains through materials design (Narančić Kovač, 2016). Secondly, the craft model was especially relevant for our teacher-participants as the areas they were focusing on were new and many lacked writing experience. Accordingly, we incorporated sample materials and an ICEKit template to provide robust scaffolding (see ‘ICEKit as a scaffold’ section below).

Based on the craft framework, we helped teacher-participants to understand materials design principles and used think-aloud techniques (i.e., the verbalizing of thought processes and decision-making) to demonstrate the application of the picturebook selection criteria. An example of such modelling is shown in Figure 1 below, which represents an extract from the final part of the ‘Picturebook Selection Guide’ presented by a teacher educator, who justifies their rationale for their choice of Perfectly Norman by Tom Percival (2017).

This kind of scaffolding provided the teacher-participants with input on, for example, the importance of asking open-questions during a read-aloud to ‘kindle children’s confidence in their own reading response as there are no ready-made answers’ (Bland, 2022, p. 77). In addition, the suggested ideas for multisensory, creative tasks for use after reading aloud intended to prompt emotional connections to the characters and themes and, thus, scaffold the action-taking cycle. The teacher-participants were then provided with two fully completed ICEKits as models for the materials co-creation phase as they explored the components of the template in greater depth. Incorporation of such collaborative discovery aimed to enhance the teacher-participants’ readiness for the co-creation of their own ICEKit based on each group’s jointly selected picturebook.

The final framework in Wallace’s tripartite model emphasises the importance of opportunities for critical reflection. These were embedded in the ICEPro course through cross-border collaboration during the co-creation of the ICEKits on the eTwinning platform. As Rampone and Ferrari (2022) explain, eTwinning currently has

around 1,000,000 teachers from 229,000 schools (all levels), based in 43 countries and speaking 28 different languages. The eTwinning platform can be used by teachers and teacher librarians to find partners from European countries in order to develop collaborative school partnerships, create authentic contexts for learning and share resources. (p. 30)

Figure 1. Modelling ideas for Perfectly Norman with think-aloud techniques

The course culminated with a critique of each group’s ICEKit draft in addition to an evaluation based on Tomlinson and Masuhara (2018, p. 59), who emphasize the importance of evaluation of materials in teachers’ classrooms (locally) and by other teachers around the world (globally). For the in-service teacher-participants (in Italy, Norway and Portugal they had their own classes), central to the project was classroom experimentation, followed by refinements to the materials based on each group’s reflections. Throughout this process, the groups were supported by regular meetings with teacher-educator-mentors. Consequently, the tripartite model operationalized within the ICEPro course functioned to facilitate the teacher-participants’ experiential learning about doing ICE through picturebooks. Moreover, the incorporation of embodied experiences, such as picturebook read-alouds at the outset of each theory-focused session, aimed to strengthen teachers’ abilities to provide the children in their classes with similarly hands-on interactions with picturebooks.

The ICEKit as a scaffold

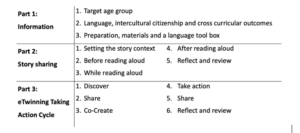

In order to support the teacher-participants in their co-creation process, the ICEKit template was structured in three parts (see Table 1). Part 1 contains the expected learning outcomes, necessary resources and task and procedural language. Part 2 is the story-sharing framework in four-stages, with a ‘setting the context’ stage, prior to the familiar before, while and after read-aloud stages associated with communicative language teaching – this part closes with a reflect and review activity. Each stage in Part 2 follows a progressive task-design, which prepares learners for what ensues, and most importantly for Part 3, which can be regarded as crucial for doing ICE. Part 3 involves six activities in an action-taking cycle where teachers and their learners engage in civic action projects, ideally through cross-border communication with partner schools, to develop as intercultural citizens.

Table 1. The ICEKit structure and components (Valente, 2022, p. 27)

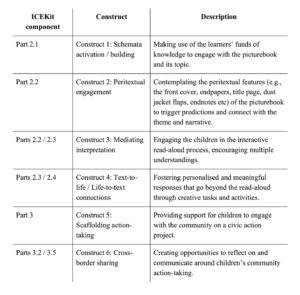

The ICEKit realizes the main objective of the ICEPELL project, that is to support practitioners to integrate ICE through picturebooks in early English language learning. As previously highlighted, this corresponds to Spiro’s notion of ‘the big idea’ which warrants reflection in relation to the six pedagogical constructs we consider as desirable for doing ICE.

- Construct 1: Schemata activation / building

- Construct 2: Peritextual engagement

- Construct 3: Mediating interpretation

- Construct 4: Text-to-life / Life-to-text connections

- Construct 5: Scaffolding action-taking

- Construct 6: Cross-border sharing

These constructs, as shown in Table 2 below, should be evident in Parts 2 and 3 of each ICEKit (see Table 1) based on the core content explored in the ICEPro course.

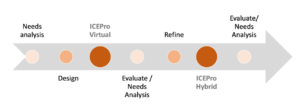

A Reflective Approach to the ICEPro Course Development

Throughout the project, we were cognisant that the ICEPro course input – even though experiential – would not inevitably lead to successful output, particularly given the variables in an ambitious, multifaceted project like ICEPELL and the newness of the terrain. With this in mind, the teacher educators adopted a reflective approach to the development of the ICEPro course and planned it iteratively in accordance with this sequence: i) Conduct needs analysis; ii) Design; iii) Deliver; iv) Evaluate / Needs analysis; v) Refine. The evaluation included feedback from the teacher-participants and an in-depth analysis of the ICEKits to uncover needs, which informed our subsequent refinements. Figure 2 represents how the iterations were implemented from the first ICEPro Virtual Course, to the second ICEPro Hybrid Course and in the future, will progress into a third version (see Mourão et al., 2022, pp. 87-91).

Table 2. The pedagogical constructs in the ICEPro course mapped to the ICEKit components

Figure 2. A reflective approach to the ICEPro course development

After each iteration, to begin our reflections, we reviewed the ICEKits in their draft versions, prior to the final edit. A detailed analysis was carried out for each of the components in ‘Part 2: Story-sharing framework’ and ‘Part 3: eTwinning taking action cycle’. To understand how the ICEPro course had shaped and supported the teacher-participants’ materials creation, we categorized our review according to the six constructs in Table 2, which we expected to be evident in the ICEKits.

After ICEPro Virtual, two ICEKits were selected from the set of six which were co-created by the teacher-participants. Following ICEPro Hybrid, a further two were chosen from the nine co-creations. Our choice was guided by the extent of editing required in the final pre-publication stage. The two ICEKits from each iteration represented one that needed minimal edits and another that needed extensive final edits in relation to the six pedagogical constructs. We purposefully differentiated the ICEKits in this way to identify examples of successful application of course content and to further analyse teacher-participants’ emergent needs as novice materials writers. These selections were not made to evidence deficiencies in the teacher-participants’ materials creation abilities, as we fully acknowledge the newness and the challenge involved. Based on the reflective approach advocated by East (2022), the analysis was undertaken to provide us with useful insights to then refine and strengthen the course programme. After we had categorized the ICEKits based on the extent of editing required, we selected one which lent itself to a strong intercultural focus and another to a more explicit citizenship focus from each ICEPro course, as shown in Table 3 below. The final published versions can be downloaded here: https://icepell.eu/index.php/icekits/

Table 3. The ICEKits selected from each course for review

For ICEPro Virtual, the draft ICEKit that needed minimal editing was ‘ICEKit#6 Cyril the lonely cloud’, based on the picturebook by Tim Hopgood (2020). This ICEKit has citizenship potential and focuses on the protagonist Cyril who travels from place to place but struggles to make friends as he always brings the rain. That is until one day, when he arrives somewhere hot that needs more water. The planned activities make cross-curricular links to the importance of water conservation and include mini-experiments around the water cycle which offer teachers and children valuable prompts for action-taking. The ICEKit that needed more extensive editing was ‘ICEKit#7 How to be a lion’ crafted around the picturebook, How to be a Lion by Ed Vere (2018). Here, the narrative centres on the protagonist, Leonard who loves poetry and subverts stereotypes of how lions should behave. Thematic links to gender stereotypes mentioned in the materials make this ICEKit a reflective vehicle for challenging the expectations placed on people of different genders in various contexts.

For ICEPro Hybrid, the draft ICEKit that needed minimal editing was ‘ICEKit#15 Unplugged’, based on Steve Antony’s picturebook (2017), which conveys a relatable tale for today’s children who spend significant periods of time online. The ICEKit comprises a set of citizenship-related materials which help show the transformative potential of (re)engagement with the outdoors and inspires children’s actions related to nature and offline games. The ICEKit that needed more extensive editing was ‘ICEKit#13 Same, same but different’, created around a picturebook by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw (2011) with its potential for intercultural learning. This story evokes memories of language learning in days gone by when children had pen pals in another part of the world, to whom they sent letters, stamps and drawings. The picturebook features two boys, one who lives in a village in rural India and the other who lives in a city in the USA. The title is a familiar refrain in South and East Asia (Ottaviano & Holt, 2011) and emphasizes how children globally have more commonalities than what separates them.

ICEPro Virtual materials evaluation and needs analysis

Our analysis of the materials for ICEPro Virtual, ICEKit#6 Cyril the lonely cloud and ICEKit#7 How to be a lion, identified strengths in Constructs 1, 2, 3 in the cases of both drafts.

Constructs 1, 2 and 3: ICEKit#6 Cyril the lonely cloud. An example of Construct 1 (schemata activation) is the series of embodied activities to both activate and extend learners’ schemata, which include the learners going outside to observe clouds, to evoke their weather-related experiences and build on cross-curricular knowledge. Construct 2 (peritextual engagement) is evidenced in the links made to this outdoor learning opportunity when title and picturebook covers are contemplated in class to trigger learners’ predictions in relation to characters, plot and theme. Such predictions are subsequently drawn on to realize Construct 3 (mediating interpretation) during the initial read-aloud with further personalization of weather experiences through questions like ‘Have you ever…?’ and further cross-curricular awareness about the formation of rainbows.

Constructs 1, 2 and 3: ICEKit#7 How to be a lion. Construct 1 is achieved through photographs to activate learners’ schematic knowledge about lions and a mime activity introduces a multisensory focus. For Construct 2, picturebook cover illustrations are also used to encourage character and plot-related predictions, extended with a focus on the inspirational quote, ‘I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it’ (Mandela). This is accompanied by elicitation of learners’ responses to the setting. Construct 3 is actualized through open questions about the characters to encourage divergent interpretations. These questions are then connected in a personalized manner to individual learners, exploring how they are all different.

Constructs 4, 5 and 6: ICEKit#6 Cyril the lonely cloud. Strengths are further evident for this ICEKit in the remaining constructs. Construct 4 (text-to-life / life-to-text connections) is evidenced through the life-to-text connections which encourage learners to photograph themselves in the rain and create a class collage. Moreover, Construct 5 (scaffolding action-taking) prompts text-to-life connections where learners co-create action-taking ideas for saving water in the local community – they compile to-do lists and then carry out agreed actions. Cross-border sharing, which is Construct 6, is systematically planned at key moments when learners jointly agree on water-saving actions as well as at the end, when they share community feedback and reflect on their experiences.

Constructs 4, 5 and 6: ICEKit#7 How to be a lion. Construct 4 is also a strength in this ICEKit, with text-to-life connections between the inspiring quotation and some world leaders chosen by the learners. Creative response in the form of ‘instruction cards for tolerance at school’ further enable life-to-text links and target deeper reflections on children’s lived experiences.

Our analysis of Constructs 5 and 6 identified weaknesses in this ICEKit draft. The idea of a fundraising event is suggested to realize Construct 5 but omits certain stages of the action-taking cycle, such as Discover, co-create and take action. A variety of creative response activities are mentioned, for example, a role play, a poster, a retelling of the picturebook by learners, a poem and a parade. But none are framed, or developed, as springboards to enable learners to take action. Construct 6, cross-border sharing, similarly does not focus on any outcomes related to community action. This suggests gaps in the understanding of the action-taking cycle and some of the progressive task design principles of materials writing.

In the published version of this ICEKit, the teacher-participants’ ideas for Construct 5 were developed into a ‘Let me be me’ parade, which is scaffolded through the action-taking cycle and accompanied by the options of a poetry show, a concert or a recital. The actions include a plan for the parade route and how to organize it with the class teacher. Families and other community members are invited to attend and give feedback. Construct 6 is systematically incorporated into the published version, with learners’ ideas about what tolerance is and with language support embedded, and an exchange of parade experiences and finally, responses to the community feedback.

Refinements for ICEPro Hybrid

The strengths identified in the drafts for Constructs 1, 2 and 3 indicate the resonance an experiential approach had for the teacher-participants when learning to mediate the materiality of picturebooks (Mourão, 2016; Veryeri Alaca, 2018). This underscores the importance of a prominent focus on schemata activation, the use of peritextual features for connections to characterization, plot predictions and interculturality and/or citizenship themes and open questions to prompt multiple interpretations. The successful application of this approach to picturebooks and materials creation, in our view, can be attributed to the systematic incorporation of read-alouds in the input. This was realized by using recordings of read-alouds embedded on the Moodle platform at the start of each core unit of learning, as well as during the live sessions on Zoom. Teacher-participants initially occupied the ‘learner’ role during the read-aloud demonstrations, and then extended their experiences by returning to their ‘teacher’ role to share ideas for mediation of their chosen picturebook. These brainstormed ideas were then developed further while they drafted their ICEKit materials on eTwinning.

The evaluation and needs analysis revealed challenges with task-activity cycles related to Construct 5, scaffolding action-taking. This highlights the teacher-participants’ need to better understand how materials can support learners to work towards a concrete outcome, such as civic engagement. As Bland (2022, p. 25) points out, teacher education should play a significant role ‘to support the transfer of learning beyond school’. Like the focus on clouds and the water cycle in ‘ICEKit#6 Cyril the lonely cloud’ and the incorporation of inspirational quotations from world leaders in ‘ICEKit#7 How to be a lion’, there was potential to expand learners’ world knowledge. Nevertheless, the traditional role subversion, reflected in the main character of Leonard in ‘ICEKit#7 How to be a lion’, was under-explored. Instead, the emphasis on child-friendly activities was prioritized over an in-depth ICE focus, which could have included actions to challenge gender stereotypes. This reflects insufficient exploration during ICEPro Virtual on ways to weave an explicit citizenship element in materials for picturebooks that allow for an intercultural orientation in tandem with a well-sequenced action-taking cycle.

In response to the needs highlighted above, the teacher-educator team modified aspects of ICEPro Virtual to provide teacher-participants with more explicit clarification of ICE. This included input through the picturebook Welcome (Barroux, 2016), which fuses the refugee and climate crises, to provide opportunities to explore the intercultural and the citizenship domains more deeply. To further support the initial co-creation process on Zoom, mentors were provided with briefing notes on two main types of action-taking. These emerged during the analysis of the six ICEKits, as follows:

Type 1 – Planning for and undertaking hands-on, tangible action-taking, where children engage in activities which have an immediate, direct impact for them to experience.

Type 2 – Planning for and undertaking a beyond-the-classroom product which involves indirect interaction with the local community while still making meaningful connections. (Valente, 2022, p. 57)

ICEPro Hybrid materials evaluation and needs analysis

Our analysis of the materials for ICEPro Hybrid identified strengths in all six constructs in the case of ICEKit#15 Unplugged. In contrast, and despite an enhanced focus on ICE and action-taking during the ICEPro Hybrid Course, our analysis of the draft ICEKit#13 Same, same but different, revealed multiple needs.

Constructs 1 to 6: ICEKit#15 Unplugged. For Construct 1, the meaning of ‘to unplug’ is concretely established and the class survey activates learners’ schemata in a personalized manner. Connections are then made, in Construct 2, to the picturebook itself with the book trailer and predictions which naturally lead into explorations of the peritext. This enables learners to notice the typography on the front cover, the differences between illustrations on the back and front covers and creator’s message provides more contextual clues. Construct 3 includes prompts for the learners to interpret the characters’ body language, which meaningfully leads into Construct 4. Here, life-to-text interpretations are encouraged between the learners’ feelings and those of the protagonist. Text-to-life connections are established by the creation of a ‘PicCollage’ which shows the learners’ relative time spent online and outdoors during free-time activities. Learners discover traditional games played by grandparents and/or other older family members when they were young for Construct 5, which is followed by a traditional games event in the community. Construct 6 is achieved by reflection with partner schools, shared virtually.

Constructs 1 to 6: ICEKit#13 Same, same but different. Letter writing is rare nowadays, especially for children, so for Construct 1, schemata is necessarily built, rather than activated in the materials. This is successfully done in a hands-on manner with sets of real stamps to concretely link to the images of stamps featured on the picturebook endpapers which realizes Construct 2. Nevertheless, the concepts of ‘sameness’ and ‘difference’ as reflected in the title, are conveyed in a decontextualized manner which lacks language support, necessary for in-depth learning. A concrete opportunity to decentre the default focus on the West is missed in the draft. Construct 3 includes ‘have a discussion’ around the different worlds to encourage individual interpretations, but it is unclear how this is to proceed in the classroom with learners. In contrast, for Construct 4, the text-to-life connections targeted by the letter writing idea to partner schools, is so overly scaffolded as a gap-fill that there is no space for individual learners’ meaning-making. For Construct 5, a collection of post reading-aloud activities are proposed which include sticky notes on a world map, a class letter, displays, and a news article, rather than a task-activity cycle with a clear citizenship-related outcome. Consequently, Construct 6 has no reflections related to action-taking to share across borders.

In the published version of this ICEKit, modifications include the context of a new child in the classroom to activate schemata about sameness and difference within the learners’ worlds. To decentre the default focus on the West, a suggestion to turn the dustjacket upside down is incorporated to introduce the main characters. Clear procedural details are provided to scaffold learners in the discussion of different worlds with questions about whether the differences impede a friendship and why or why not. Life-to-text connections enable learners to explore family diversity via a ‘Where am I from?’ mini-project, which extends to an investigation of family diversity in the whole school. Outcomes are shared with partner schools to discover each other’s diverse communities to exchange reflections and feedback.

Refinements for future ICEPro courses

Given that the goal of the ICEPELL Project is to evoke a social conscience, when materials are created around picturebooks which portray a monolithic notion of culture-as-nation they should explicitly encourage learners to read against the text (Leland, et al. 2013). As Bland (2022, p. 22) maintains, this enables ‘[learners] to discover any absences and misinterpretations in their reading’. The published version of ICEKit#13 Same, same but different therefore incorporated a focus on ‘Being more aware’, with prompt questions such as: ‘Do all Indian families live in rural areas?’, ‘Do all American children live in cities?’, ‘Does a typical Indian or North American family exist?’.

The most extensive revisions were within Constructs 5 and 6, especially for action-taking. The eventual modifications to the published version applied Short’s (2011, p. 50) ‘authentic action’ model, whereby recognition and celebration of diversity through action-taking starts with the learners themselves, moves through the school and expands into the community. We attribute the challenges the teacher-participants initially encountered with the action-taking cycle to insufficient exploration of the fusion between citizenship and interculturality (Barrett & Golubeva, 2022). In addition, there was scant attention to the importance of reading against the text to help teacher-participants challenge national stereotypes. It would be valuable to include a focus on the use of text sets during a future ICEPro course, to avoid a single-story portrayal of life in any national context. Therefore, in terms of approaches to teacher development within materials writing, there continued to be an imbalance with a bias towards the craft model, with insufficient application of the applied science and reflective models (Hughes, 2022). Increased session time would be required to further raise teacher-participants’ awareness of authentic action-taking during future ICEPro courses.

In essence, the changes we have made mark a return to the ICEPELL project’s original plan for a fully face-to-face teacher development course, but extended to 30 hours. In terms of input, a new Day 1 session focuses on ‘Culture and Citizenship’ through the vehicle of The Queen’s Hat by Steve Antony (2014), a picturebook which represents a tourist lens on culture. The accompanying tasks will enable teacher-participants to read against the text and identify strategies to help learners become critical readers. This is followed by another new session on picturebooks and action-taking. This will explore the concept of ICE more deeply, with teacher-participants identifying texts that lend themselves to mediation of intercultural and/or citizenship themes in picturebooks from the ICEPELL canon.

Collaborative work will similarly be extended, with the incorporation of discovery tasks based on a new ICEKit developed by the ICEPELL consortium for Barroux’s Welcome. The sample will be used in an interactive manner with mentor support, to achieve the goal of raising teacher-participants’ awareness of how the ‘Part 3: eTwinning taking-action cycle’ can prompt a focus on the environment and help learners act in solidarity with refugees. The applied science and reflective models will also be strengthened throughout future iterations. Familiarity with the tripartite model will be increased amongst the teacher educators to enable them to develop teacher-participants as materials writers. There will also be an explicit emphasis on progressive task design and coherence within materials, so that each Part of the ICEKit, and its respective stages, incrementally build on each other.

Conclusions and Implications

In terms of the materials writing phase during the ICEPro course, teacher-participants’ experiential engagement in picturebooks helped to evoke their ideas for Construct 1, that is activation of learners’ schemata in an embodied manner. Likewise, the teacher-participants’ engagement in read-alouds, first as participants and then as teacher-mediators, helped them to explore Construct 2, i.e. the materiality of the picturebook format as a point-of-entry into ICE themes. For Construct 3, the importance of open-ended questions for the read-alouds and the use of learners’ predictions to prompt diverse interpretations are successfully actualized within the co-created materials.

Text-to-life and life-to-text connections, which represent Construct 4, are largely present after reading-aloud in the form of personalized, creative response tasks and activities. However, in some instances, modifications to the materials were necessary due to insufficient scaffolding and coherent development of learning. In Construct 5, a robust action-taking cycle with discovery and co-creation towards a common outcome was lacking in some of the materials. This requires increased emphasis on the conceptualization of ICE, in addition to deeper reflection on ways to ensure an explicit citizenship outcome, which can achieve Construct 6 through systematic sharing with learners in partner schools.

Teacher development based on creating materials around picturebooks for ICE requires further research. This includes focus groups to explore the experiences of in-service teachers who have co-created and implemented such materials in their classes, with a focus on the strengths and weaknesses and the future modifications they could make to their materials. In addition, lesson observations and reflective journals by teacher educators and teacher-participants, while drafting and trialling, would offer valuable insights. A particular research lacuna is how materials can support one of the most challenging aspects of doing ICE, i.e. studies of action-taking in the community, at local, national, global levels by early English language learners and their teachers. Data from such studies would enable teacher educators to more confidently answer Spiro’s call for teacher empowerment and for ‘… teachers to take their place alongside materials writers as co-creators’ (2022, p. 478).

Bibliography

Adeola, Dapo (2021). Hey You! Nancy Paulsen Books.

Antony, Steve (2014). The Queen’s Hat. Hodder Children’s Books.

Antony, Steve (2017). Unplugged. Hodder Children’s Books.

Barroux. (2016). Welcome. Egmont.

Davies, Nicola, illus. Rebecca Cobb (2018). The Day War Came. Walker Books.

Hopgood, Tim (2020). Cyril the Lonely Cloud. Oxford University Press.

Kostecki-Shaw, Jenny Sue (2011). Same, Same, but Different. Christy Ottaviano Books.

Percival, Tom (2017). Perfectly Norman. Bloomsbury.

Rodrigues, André, Ribeiro, Larissa, Desgualdo, Paula & Markun, Pedro (2020). The President of the Jungle. Nancy Paulsen Books.

Vere, Ed (2018). How to Be a Lion. Puffin Books.

References

Barrett, M., & Golubeva, I. (2022). From intercultural communicative competence to intercultural citizenship: Preparing young people for citizenship in a culturally diverse democratic world. In T. McConachy, I. Golubeva & M. Wagner (Eds.), Intercultural learning in language education and beyond: Evolving concepts, perspectives and practices (pp. 60-83). Multilingual Matters.

Bland, J. (2022). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury.

Bortoluzzi, M., Bertoldi, E., & Marenzi, I. (2021). Storytelling with children in informal contexts: Learning to narrate across the offline/online boundaries. In M. G. Sindoni & I. Moschini (Eds.), Multimodal literacies across digital learning contexts (pp. 72-89). Routledge.

Bredella, L., & Delanoy, W. (1996). Introduction. In L. Bredella & W. Delanoy (Eds.), Challenges of literary texts in the foreign language classroom (pp. vii-xxviii). Gunter Narr.

Brunsmeier, S. (2017). Primary teachers’ knowledge when initiating intercultural communicative competence. TESOL Quarterly, 51(1), 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.327

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (2008). From foreign language education to education for intercultural citizenship. Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (2021). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence: Revisited. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800410251

Carvalho, P. C. P. (2020). Citizenship education in primary English in Portugal: Picturebooks as windows and mirrors [Unpublished master’s thesis, Nova University Lisbon, Portugal].

Council of Europe (2018). Reference framework of competences for democratic culture. Volume 1, 2, 3: Context, concepts and model. Council of Europe.

Dolan, A. M. (2014). You, me and diversity: Picturebooks for teaching development and intercultural education. Trentham Books.

Doyé, P. (1999). The intercultural dimension: Foreign language education in the primary school. Cornelsen.

East, M. (2022). Mediating innovation through language teacher education. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009127998

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2014). Tell it again! The storytelling handbook for primary English language teachers. British Council.

Ellis, G., & Mourão, S. (2021). Demystifying the read-aloud. English Teaching Professional, 36, 22-25.

Ellis, G., & Mourão, S. (2022). Identifying quality in asynchronous, pre-recorded picturebook read-alouds for children learning English as another language. In A. Paran & S. Stadler-Heer (Eds.) Taking literature online: New perspectives on literature in language learning and teaching (pp. 47-70). Bloomsbury.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2017). Citizenship education at school in Europe – 2017. Eurydice Report. Publications Office of the European Union.

Fitzgerald, H. (2007). The relationship between development education and intercultural education in initial teacher education. DICE Project.

Guilherme, M. (2012). Critical language and intercultural communication pedagogy. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication (pp. 357-371). Routledge.

Heggernes, S. L. (2019). Opening a dialogic space: Intercultural learning through picturebooks. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 7(2), 37-60.

Hughes, J. (2022). Training materials writers. In J. Norton & H. Buchanan, (Eds.). The Routledge handbook of materials development for language teaching (pp. 511-526). Routledge.

Ibrahim, N., Becker, C., & Mourão, S. (2022). Picturebook selection. In ICEPELL Consortium, (Eds.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 41-46). CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

ICEPELL Consortium (2022). The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning. CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

Leland, C., Lewison, M., & Harste, J. (2013). Teaching children’s literature. It’s critical! Routledge.

Lopes, H. M. da M. (2020). Citizenship and language education. Picture books: New opportunities for young teenagers [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Nova University Lisbon, Portugal].

Masoni, L. (2019). Tale, performance, and culture in ELT storytelling with young learners. Cambridge Scholars.

Matos, A. G. (2012). Literary texts and intercultural learning. Peter Lang.

Morgado, M. (2018). Minority cultures in your school. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 6(2), 28-45.

Morgado, M. (2019). Intercultural mediation through picturebooks. Comunicação e Sociedade, Special Issue, 163-183. https://journals.openedition.org/cs/927

Mourão, S. (2016). Picturebooks in the primary EFL classroom: Authentic literature for an authentic response. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 4(1), 25-43.

Mourão, S., Ferreirinha, S., & Jakisch, J. (2022). The ICEPro professional development course. In ICEPELL Consortium (Eds.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 79-91). CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

Narančić Kovač, S. (2016). Picturebooks in educating teachers of English to young learners. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 4(2), 6-26.

Ottaviano, C., & Holt, H. (2011, September 13). Same same, but different [Review]. KIRKUS. https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/jenny-sue-kostecki-shaw/same-same-different/

Porto, M. (2016). Ecological and intercultural citizenship in the primary English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom: An online project in Argentina. Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(4), 395-415. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2015.1064094

Pulverness, A. (2014). Materials for cultural awareness. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing materials for language teaching (pp. 426-478). Bloomsbury.

Rampone, S., & Ferarri, F. (2022). eTwinning. In ICEPELL Consortium (Eds.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 30-34). CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

Rader, D. (2018). Teaching and learning for intercultural understanding. Routledge.

Risager, K. (2022). Culture and materials development. In J. Norton & H. Buchanan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of materials development for language teaching (pp. 109-122). Routledge.

Roche, M. (2015). Developing children’s critical thinking through picturebooks: A guide for primary and early years students and teachers. Routledge.

Short, K. G. (2011). Children taking action within global inquiries. The Dragon Lode, 29(2), 50-59.

Sipe, L. R. (2008). Storytime: Young children’s literary understanding in the classroom. Teachers College Press.

Spiro, J. (2022). Making the materials writing leap: Scaffolding the journey from teacher to teacher-writer. In J. Norton & H. Buchanan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of materials development for language teaching (pp. 475-487). Routledge.

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2018). The complete guide to theory and practice of materials development for language learning. Wiley Blackwell.

Utdanningsdirektoratet (2019). Læreplan i engelsk (ENG01-04). Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/lk20/eng01-04

Valente, D. (2022). Picturebook materials development. In ICEPELL Consortium (Eds.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 53-58). CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

Vasquez, V. M., Janks, H. & Comber, B. (2019). Critical literacy as a way of being and doing. Language Arts, 96(5), 300–11.

Veryeri Alaca, I. (2018). Materiality in picturebooks. In B. Kümmerling Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 59-68). Routledge.

Volkmann, L. (2015). Literary literacy and intercultural competence: Furthering students’ knowledge, skills and attitudes. In W. Delanoy, M. Eisenmann & F. Matz (Eds.), Learning with literature in the EFL classroom (pp. 49-68). Peter Lang.

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge University Press.