| Disturbing the Still Water: Korean English Language Students’ Visual Journeys for Global Awareness

Eun Young Yeom |

Download PDF |

Abstract

In the score-driven South Korean secondary-school English language teaching (ELT) contexts, the multicultural picturebook written in English is not appreciated as a visual art form that can promote global awareness, visual literacy and enhanced visual thinking skills. The current study aimed to examine whether book club discussions based on visual analysis can help Korean secondary-school language students decode messages embedded in picturebook images. The study focused on marginalized immigrant youths, as depicted, for example, in Allen Say’s Tea with Milk (2009). In the study, South Korean secondary-school book club members participated in communal visual thinking, and moved between the visual details and the entire visual text. In so doing, they reflected on their lives and other ways of being, employing empathy and perspective taking. The investigation aimed to discover whether secondary-school students can develop aspects of global awareness while learning the global language, English.

Keywords: multicultural picturebooks; global awareness; empathy; visual analysis; visual literacy

Biodata:

Eun Young Yeom worked as an in-service middle-school English teacher for 12 years in South Korea. She is now a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia majoring in Literacies and Children’s Literature. She conducts research on how communal visual thinking activities that incorporate English multicultural picturebooks can improve secondary-school students’ visual literacy, L1 and L2 reading comprehension and an empathetic understanding of marginalized people’s experiences. [end of page 1]

Introduction

With relatively simple sentence structures and visual appeal, English-language picturebooks can provide a meaningful context for language students to learn English (Bland, 2013; Ghosn, 2002). Discussing the aesthetic features of picturebooks can take the readers outside of themselves, their own experiences, realities and points of view (Wissman, 2019). The favourable impact of picturebooks on primary language students is well documented (see Burke & Peterson, 2007; Murphy, 2009; Nicholas, 2007). However, few studies document how visual analysis discussions of picturebooks and subsequent interpretive writing can improve secondary-school students’ English learning (Yeom, 2018). In addition, their empathetic understanding of cultural diversity based on visual analysis discussions and interpretive writing has been neglected.

With authentic English vocabulary and sentence structures (Ghosn, 2002), multicultural English picturebooks in particular can provide ‘insights into other cultures by inviting students to engage in the perspectives and experiences of members of these cultures’ (Alter, 2018, p. 26), and these insights can enhance students’ empathy and respect for others (Parsons, 2016). Nikolajeva (2013) explains that empathy building and understanding others based on visuals is possible, thanks to the theory of mind, which is ‘the capacity to understand how other individuals think. Empathy refers more specifically to the capacity to understand how other people feel’ (p. 250). Hence, interpreting the images in multicultural picturebooks can presumably support secondary-school students in changing perspective or perspective taking, and achieving empathetic understanding of people from different walks of life. This can help them grasp different cultural values and norms (Bland, 2013; Callow, 2017; Mourão, 2013), or a so-called global awareness (Crawford & Kirby, 2005; Hanvey, 1982) while learning a global language, English.

Unfortunately, in South Korean language learning settings in particular, little attention is being paid to the potential of English multicultural picturebooks as a ‘visual art form’ (Kiefer, 2008), which can extend students’ visual reading experience into improved global awareness. Very few studies in South Korean settings have examined how sociocultural visual analysis (e.g. book club discussions) and subsequent interpretive writing can improve the aesthetic understandings of multicultural English picturebooks; how these understandings can be extended to global awareness based on empathy and [end of page 2] perspective taking; and what Korean secondary-school students of English can glean beyond the L2 (English) to L1 (Korean) translation. Thus, the current study was guided by the following questions:

- In what ways do visual analysis and book club discussions help Korean secondary-school students of English reach an understanding of marginalized immigrant youths’ experiences?

- What kinds of understandings regarding marginalized immigrant youths emerge during Korean secondary-school students’ book club discussions and in their follow-up written responses?

It must be noted that discussions and writing activities were conducted in the students’ L1 (Korean). In this way, L2 students can express their thoughts more effectively, because they can make more appropriate remarks without the risk of making mistakes in L2 (Cook, 2001), while a sense of safety is promoted in the learning process (Dailey-O’Cain & Liebscher, 2009).

Literature Review

This section provides a brief overview of global awareness and how the aesthetic features of multicultural English picturebooks are used to enhance global awareness in ELT settings.

Global Awareness and its Dimensions

Global awareness was first comprehensively proposed by Hanvey (1982), who suggested five dimensions that can inculcate students regarding the diversity and interconnectedness of humanity – that is, perspective consciousness, state-of-the-planet awareness, cross-cultural awareness, knowledge of global dynamics, and awareness of human choices. Hanvey (1982) used the term ‘global perspective’ to denote global awareness, both of which were presumably interchangeable. He argued that teaching from a global perspective could raise students’ global awareness with diverse perspectives and sensitivity. His view has been revised and refined by later scholars (Hicks, 2003; Kirkwood, 2001; Merryfield, 2000). Despite some variations, these scholars’ ideas promote ‘human cooperation, the interdependence of human systems, and the fostering of cross-cultural understandings, such as the development of empathy and perspective taking’ [end of page 3] (Crawford & Kirby, 2008, p. 57, my emphasis). Most importantly, global awareness can act as a stepping stone for students to think at a higher level in literacy classrooms. Students can be involved with ‘critical practices that integrate global and multicultural dimensions into literacy teaching and learning’ (Yoon et al., 2018, p. 205).

Multicultural Picturebooks for Global Awareness Based on Aesthetic Understanding

Young readers’ ‘metacognitive skills can be developed and built on in order to help them become more critical and discerning’ viewers and readers (Arizpe & Styles, 2016, p. 98). Few studies, however, have tapped into the favourable influence of visual analysis of multicultural picturebooks on students’ English learning and global awareness. Although not involving active visual analysis on the part of learners, Kaminski’s (2013) study also highlights the beneficial role of the visual components of picturebooks on language learners’ English vocabulary improvement and story reconstructions. Kaminski (2013) argues that pictures assist language learners in understanding the story and make the story more memorable by triggering their interest.

Mourão (2013) conducted an empirical study with Portuguese secondary-school students using Shaun Tan’s (2010) The Lost Thing. While engaging in visual analysis of refugees’ experiences, the participants transacted with both the textual and the visual components, and interacted with their peers. Their discussion was fostered by inter-animation between pictures and words, or ‘carrying semantic traces from the pictures to the words and from the words to the pictures’ (Bland, 2013, p. 21). According to Mourão (2013), the participants showed their appreciation of inter-animation and of the value of visual components in their subsequent interpretive writings after small group discussions.

In Korean English learning, at primary level in particular, many studies have shown that reading English-language picturebooks can yield benefits in children’s reading and writing skills development (Cho & Kim, 2016; Kwon & Kim, 2012; Park, 2011; Shin & Kim, 2017). However, little research has examined the positive correlations between the use of multicultural picturebooks as a visual art form and Korean secondary-school students’ understanding of the multicultural aspects of the world. Instead, much attention has been placed on verbal literacy development, such as vocabulary improvement (Kang, 2010; Kim & Kim, 2010) of primary-school children. Bae (2012) also mentions that integrating multicultural literature into Korean middle-school ELT can act as a springboard for the [end of page 4] students to develop general literacy ability and intercultural sensitivity, but does not take visual images into account when explaining the increased level of intercultural sensitivity.

However, it should be noted that decoding the synergistic relationship between the verbal and the visual can create ‘a playing field where the reader explores and experiments with relationships between words and the pictures’ (Wolfenbarger & Sipe, 2007, p. 274). If multicultural picturebooks are incorporated into the classroom, examining the synergistic relationship between written and visual modes can raise students’ awareness regarding cultural diversity and what it means to be marginalized (Callow, 2017), which validates the need for the inclusion of visual analysis discussions in picturebook reading comprehension processes.

Methodology

Theoretical Framework

This study looked into how visual analysis discussions can mediate secondary-school language students’ more profound understanding of visual images, with sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1986) as the basic tenet of the theoretical framework. Discussion activities provided the participants with ‘shared dialogue and joint activities, criticism, rejection and resistance to events that occur on the social level’ (John-Steiner & Meehan, 2000, p. 35). Students’ interactions and responses are not seen as a one-way information transfer. Rather, they are regarded as exchanges of knowledge bases that are co-built and revised in sociocultural interactions during discussions (McVee & Boyd, 2016).

Moreover, during discussions on the multicultural picturebook that we were reading, the students were asked to take aesthetic stances (Rosenblatt, 1978) while simultaneously referring to their cultural backgrounds. Thus, culturally situated reader-response theory (Brooks & Browne, 2012) was also incorporated into the data analysis. The participants transacted with their personal histories and experiences, which were inseparable from their cultural backgrounds. Culturally situated reader-response theory was influenced by Rosenblatt’s (1982) transactional reader-response theory in that both theories consider reading as ‘a transaction, a two way process involving a reader and a text at a particular time, under particular circumstances’ (Rosenblatt, 1982, p. 268), one of which is a particular cultural circumstance. Culturally situated reader-response theory [end of page 5] suggests that readers’ responses emanate from their homeplace position, which provides individuals a sense of cultural and social identity. The homeplace position encompasses current positions as peers, family members or members of a community or an ethnic group.

Data Collection

The data were gathered from weekly book club discussions that the author as teacher-researcher organized and managed. The activities took place in 2016 at a middle school located in a South Korean metropolitan area. At the beginning of the spring semester, the teacher-researcher made an announcement to the eighth graders and ninth graders that a weekly book club would be launched, and that they should actively participate in the book club discussions on Wednesdays after school. It was clarified that the club would not be included in, or related to, the regular curricular courses. Thus, it would not affect their grades. Twelve students (seven 8th graders and five 9th graders) applied, and were admitted into the club, after face-to-face interviews with the teacher-researcher. The interview questions were whether the students enjoyed reading and discussing literature, and were prepared to accept constant observation and interviewing. Pseudonyms were used for ethical reasons.

Before starting the first book club meeting, consent was received from the participants to audiotape the book club sessions and to gather their written responses for research purposes only. The book club meetings were held every Wednesday after school at the teacher-researcher’s language arts classroom and were audio-recorded and later transcribed for analysis. After each visual analysis discussion, the participants wrote their final thoughts on the worksheet, which contained the same questions we covered during the discussions. Following the last discussion, the students wrote a response journal regarding their own opinions on the protagonist’s experience on foreign soil.

After reading Kate DiCamillo’s The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane (2006) as their first book, the teacher-researcher gave the participants various options, among which were multicultural picturebooks such as Allen Say’s Tea with Milk (2009). Tea with Milk, in particular, received much attention from the participants because of its high-quality illustrations. The participants agreed to use Tea with Milk in their next book talks, which became the source of the current study. The activities that were pertinent to the current research took place from May 11th to June 8th, 2016. [end of page 6] This artistically exquisite picturebook portrays the story of an independent Japanese girl named May, who must grapple with discrimination and misjudgement because her American cultural identity constantly clashes with Japanese cultural standards. Originally born and raised in California until the age of fifteen, she expresses her frustration towards life in Japan, where her Japanese-American identity is marginalized.

Data Analysis

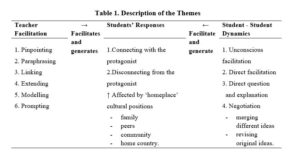

The data analysis procedure employed thematic analysis (Brown & Clarke, 2006) and was ongoing and recursive. At the beginning of the analysis, the teacher-researcher studied the focal data – participants’ written responses and transcripts from book club discussions – in order to find ways to generate descriptive codes to capture themes that emerged from the data. The data were examined using two separate analyses, with the sentence serving as the unit of analysis. The first round of analysis examined how visual analysis discussions can entail in-depth analysis of visual and textual components. For the second round, the results from the first round of analysis were linked to the participants’ responses to the protagonist’s inner conflicts. In this process, it became more apparent that the participants’ comments acted as a mirror that reflected their emotions, identities, subjectivities, world views and life histories; and the responses became the broader themes in the analysis. The emerging themes are summarized in Table 1.

[end of page 7]

Results

In the first part of this section, I will illustrate how teacher facilitation and student-student dynamics inspired the participants’ deep appreciation for visual images. Subsequently, the participants’ specific responses regarding the marginalized protagonist will be discussed in relation to their cultural positions. In this way, it can be shown how the participants developed and co-constructed the idea of diversity within a sociocultural milieu.

Visual Analysis in Sociocultural Interactions

Teacher facilitation. The protagonist’s frustration and transformative self are well expressed in traditional Japanese clothing and bold Western outfits. Although it seems far-fetched to assume that clothes are directly related to an individual’s complex identity, clothing choices can reflect an individual’s personality and sense of self to some extent (Feinberg, Mataro, & Burroughs, 1992). In the first session of the discussions, the teacher-researcher asked questions regarding the meaning of the insert cover (title page). In this image, little May is dressed up just like the white European doll next to her, which connotes that she identifies with a white, European-American appearance. The following discussion touched upon the issue of clothes as identity performance:

Teacher: Take a good look at the insert cover. What do you see in this picture?

Yuna: A girl and a doll.

Teacher: OK, a girl and a doll. What more can we find in this picture? For example, what are the differences and similarities between the two? (1)

Lee: The girl is a typical Asian and the doll is a typical white European.

Teacher: They might be the typical image of people from a particular continent. And what more can we find?

Lynn: They are wearing same outfits.

Teacher: Yes, they are in almost the same outfits. Why do you think the girl is wearing her dress in the same way as the doll? Any opinions?

Lynn: Well, I think she is deluding herself as a white American. But she is genetically Asian.

Teacher: She could be delusional. But clothes can be your projected self. Your private ideal self could be reflected in your fashion choices. (2) [end of page 8]

Yuna: Then, it shows her self-will to pursue the American life style as she knows it better than the Japanese one.

Teacher: Maybe. What about the overall mood of this picture? (3)

Sue: Very dark. The background is black.

Teacher: Why do you think the background is dark in this picture?

Sue: Because the story will be very gloomy. (4)

[trans. from Korean by the author]

In the transcript, the teacher pinpoints the visual features (1 & 3) that led to the decoding of embedded messages within them (2 & 4). Also, the teacher-researcher hinted at the symbolic meaning of one’s fashion choices. Yuna might have been mentally engaged with the teacher’s conversation with Lynn, and she pushed the conversation to the next level of thinking when she heard the role of fashion choices in expressing identity. Yuna linked the clothes to May’s self-will and life styles as seen in the following written response:

The protagonist wears a dress similar to that of the doll, and the doll looks like a typical Westerner. Hence, this image connotes that the girl has a strong self-will to pursue a life in the USA. Also, she looks really gloomy. I think her rebellious attitude toward her coercive parents is expressed through her solemn facial expressions. Why does she look so gloomy? Her strong will to stay in the USA. [trans. by the author]

Yuna also made an observation regarding the protagonist’s emotional expressions based on recognizable features, because the ‘manifestation of basic emotions, notably facial expression’ (Nikolajeva, 2013, p. 251) is easily recognizable. She linked this observation to the protagonist’s self-will, which she mentioned during the discussion. Starting with the small visual characteristics pinpointed by the teacher, Yuna weaved the symbolic meanings of clothes and emotional features together in order to understand the protagonists’ feelings.

Sue made comments on the illustrator’s choices such as colour and mood, just as she mentioned during the discussion. For example, Sue wrote:

Based on the almost black background and very gloomy mood showing in the picture itself, the girl might be very downhearted. It’s not normal for this little girl. I wonder [end of page 9] what kind of story she has and how the story will evolve. But it will be very gloomy. [trans. by the author]

Within this small group conversation, Sue constructed her own interpretation in addition to the co-constructed, collaborative meaning-making process. The teacher-researcher helped her revisit and expand her own understanding regarding the symbolic meanings of colours that are socioculturally constructed (Serafini, 2014), and stimulated her to use her own semiotic knowledge to decode the messages embedded in the colour codes. Sue then also observed the protagonist’s facial expressions and made intertextual links to her own socioculturally constructed background knowledge concerning the protagonist’s characteristic behaviour: ‘When reading images, we are looking for recognizable external tokens of emotions, because this is how we use theory of mind in real life’ (Nikolajeva, 2013, p. 251). Looking for the recognizable clues from the protagonist’s facial expressions, Sue found the protagonist to be a downhearted little girl, which she regarded as very unusual for a young child.

It must be noted here that the teacher-researcher’s pinpointing and modelling concepts served as scaffolding that allowed the students to move further into their ‘zone of proximal development (ZPD)’ (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). When the more experienced learners facilitate the understanding of the less experienced ones, the ZPD comes into play. Moreover, language played an indispensable role in mediating the participants’ internal thought processes, and social interaction through language served as an impetus for developing knowledge and thinking (Vygotsky, 1978).

Student interactions as co-inquiry. The participants interacted as if they were co-inquirers in excavating hidden gems that had been overlooked by casual explorers. Mediated through conversations, the process of analysing illustrations was not merely a list-making activity, it was a complex and dynamic process. For example, they were able to co-construct the meaning of the visual image based on their knowledge of visual grammar:

Teacher: Take a look at the image on page 11. What do you see in this picture?

Yuna: May is practising the traditional tea ceremony.

Teacher: Maybe it was a practice. What more can we find in this picture? [end of page 10]

Lee: The grandfather is very intimidating.

Teacher: He could be her grandfather or her teacher. And he looks intimidating. What makes you say that?

Lee: I don’t know. Maybe because he is wearing a black kimono?

Jin: That’s what I thought. He is wearing black and he is much bigger than May.

Yuna: Oh, I see! He is taking up more than a half of the picture, and the darker colour draws our attention as well.

Jin: And look at their clothes. There are no wrinkles. It may signify May is coerced to follow very strict rules.

Yuna: Yeah, I know. It must be suffocating.

[trans. by the author]

In this conversation, the participants considered not only the content of the image but also its compositional features to make meanings in the picture. The participants did not use the technical terms of visual grammar explicitly, however, they were aware of compositional structures – ‘how elements are positioned and the potential meanings of these positions’ (Serafini, 2014, p. 65). Different uses of position, colour and sizes can create different meanings. For example, characters positioned at the centre of the page, larger objects, and darker colours often generate the meaning of power (Serafini, 2014). By placing the old teacher in the foreground and putting the girl at the back, and by describing the teacher as bigger and in darker clothes than the girl, the illustrator gave much more salience to the teacher than the girl: this may signify that the old teacher had more power than May the girl protagonist.

The conversation above illustrates how the participants figured out the coded meaning within the visual image by incorporating their knowledge of visual compositions; and how the decoding process became more refined with more analytical observation. Lee first brought up the colour codes, which are socioculturally and historically constructed (van Leeuwen, 2011) – black as dark and creating a somewhat scary mood. Jin added her own observation to Lee’s comment, and they unconsciously helped Yuna to make more detailed observation. In addition to the analysis of visual grammar, Jin also commented on the content of the visual image. such as unwrinkled clothes. She associated the unwrinkled [end of page 11] clothes with organized and orderly behaviour, which is a socioculturally cultivated concept. All of these interactions made it possible for Yuna to conclude that this environment must be suffocating for May.

As suggested in the example above, the book club discussions became the site for collaborative inquiry in which book club members co-constructed their knowledge through social interactions. Each student did not merely make use of cultural knowledge. Instead, they actively made contributions to knowledge resources, and made textual or intertexual links to their past experiences. In the subsequent interpretive writing, Yuna wrote:

May has to live in a very authoritarian culture. And her neatly kempt hair and perfectly ironed traditional clothes show how strict her surrounding environment is. Her stern face intensifies the forbidding mood of the picture. [trans. by the author]

As seen in her writing sample, the social interactions provided her with opportunities to learn how to use visual grammar from her peers, and to actively reconstruct meanings by attaching her own additional thoughts. For these students, ‘examining and talking about art created an arena for pushing meaning-making capacities, and therefore their thinking and language’ (Yenawine, 2013, p. 110).

Students’ Understandings of a Marginalized Youth’s Experiences

Connecting to the protagonist. Being uprooted from one’s home culture can create a sense of loss in the individual, similar to what May had to face in the story. The participants empathized with the protagonist’s confusion, anger and frustration by drawing upon the concept of familiarity – food, clothing, language, and social groups. An intense debate erupted when they discussed the image of the lonesome girl standing in the middle of an empty school yard:

Teacher: Suppose that you were May in this situation. How would you feel and what would you do to handle this situation?

Hani: I would feel very depressed and might resist every rule imposed on me because that’s not what I am. It would be devastating if my parents were to force me to turn into a totally different person following [end of page 12] unaccustomed rules.

Teacher: Then what would be the most challenging part for you to handle?

Hani: Being apart from my closest friends and not being able to communicate in Korean.

Teacher: You can learn English. Why is mother tongue so important for you? Any thoughts?

Sun: Oh, that is very important. Korean is the most effective medium for me to communicate with people. Even if I am fluent in English, that cannot substitute what the Korean language can do. Maybe I can make friends with Americans; however, there is something deeper with my Korean friends.

[trans. by the author]

Apparently, emotional wholeness generated from intimacy has given the participants a sense of belonging, since ‘during middle school, the peer group heavily influences youth’ (Brooks & Browne, 2012, p. 82). Moreover, their Korean mother tongue bridges their worlds and builds shared understanding among them. Hani and Sun recognized the dual role of languages. The adequate level of foreign language proficiency may provide language learners with a window for better understanding other cultures and people. However, the most familiar mother tongue can blend and mould different pieces of building blocks of unique persona that cannot be substituted by a foreign language. For the middle school participants, the homeplace position of peers (Brooks & Browne, 2012) who speak the same mother tongue might well have generated their sense of belonging and being rooted.

The idea of building a new social self on foreign soil was mentally agonizing for them, just like it was for May in the story. In order to understand the protagonist, the participants reflected on themselves. In so doing, they grasped the idea that their sense of self relied on their sense of belonging by feeling grounded and by searching for emotional wholeness. They thought that they would struggle between an unaccustomed world, in which they were forced to fit in and adjust, and their original home which they had left behind. Sun commented on the issue of being displaced from one’s home country in her written response as follows: [end of page 13]

My value system is composed of distinctively Korean cultural identity, which I am proud of. If I were in May’s shoes, I would be disturbed by the cultural differences, and would be depressed due to the lack of emotional support. It is possible that I can pretend to be like them, and emulate their behaviour; however, it cannot change who I really am. [trans. by the author]

Like other participants, Sun was able to put herself in May’s shoes, since the comfort of familiarity generated solidarity and integrity within her sense of self. As seen in the conversation and the written extract above, the participants incorporated ‘homeplace positions’ (Brooks & Browne, 2012), including friends and language to transact with the story about a marginalized immigrant youth, thereby enabling them to empathize with the agonizing protagonist. In other writing samples, the participants often mentioned family and food as key factors that can generate a sense of comfort and familiarity.

Disconnecting from the protagonist. While some students, for example, Hani, said that maintaining their original cultural identity would come first in the acculturation process, other students were afraid of looking different and becoming alienated from the majority of the people from the host culture. One of the coping mechanisms of living in a foreign country that they mentioned was blending into the host culture by appropriating communicative skills and following the societal norms of the host culture. Lynn, in particular, consistently mentioned that she would follow the footsteps of her parents and would go the extra mile to make friends with people from the host culture. When we talked about the scene in which the protagonist decided to move out from her parents’ house and headed to Osaka, Lynn responded as follows:

Lynn: But I will live with my parents, anyway. I would not take such a giant step for an adventure. It is too scary.

Teacher: What? You are the most confident student that I know. You always speak up in class.

Lynn: But this is different. I need my parents to be my anchor. Through this chance of discussing May’s experience, I realize that I am so scared of encountering life-altering experiences and adventures; and that’s why I [end of page 14] admire May. She is so brave. I would rather stay with my parents and try to make it work. That is the best I can do.

[trans. by the author]

The book club discussions helped Lynn to come to terms with her undiscovered self. In May, she found someone whom she was not. It seemed that she was aware of who she was and what constituted her inner self. Moreover, a better grasp of her sense of self served as a platform for her to understand the magnitude of the protagonist’s decision. She was aware that the protagonist made a life-altering decision, which impressed her greatly. To Lynn, the emotional comfort generated by her family outweighed the importance of gaining independence from her parents. Thus, the homeplace position of family (Brooks & Browne, 2012) might have led her to distance herself from the protagonist’s decision.

Although not mentioned in the transcript above, Sun also thought she would try her best to fit into the new society instead of leaving her parents. However, she made it clear that her choice did not necessarily signify replacing her cultural identity rooted in her home country. She wrote:

Trying to be acculturated into the host culture does not necessarily destroy my original cultural identity. My original self, which has been constructed for my lifetime, cannot be substituted by later international experiences. [trans. by the author]

Conclusion and Implications

With the help of culturally sensitive, well-written, and visually appealing multicultural picturebooks, ‘teachers can help their students learn to decode images, making connections between culture and environment, while gaining a greater understanding of other ways of being, both in and beyond their immediate world’ (Reisberg, 2008, p. 258). In this sense, the multicultural picturebook chosen for this study also provided student participants in ELT settings with a safe haven to experience other cultures and ideas that they had not considered before. While the teacher-researcher facilitated the process, the participants were able to make intercultural connections based on empathy and perspective taking.

In addition, intelligent observation of a multicultural picturebook acted as an impetus for the L2 South Korean secondary-school readers to employ more discerning eyes, to decode embedded messages encrypted within the visuals by oscillating between [end of page 15] the details and the whole visual text, and to reflect on their lives and other ways of being. As Nikolajeva notes (2013) that ‘visual images are powerful means to invite readers to engage with texts and that picturebooks are perfect training fields for young people’s theory of mind and empathy’ (p. 254). Regarding the indivisibility of seeing and thinking, Arnheim (1970) also mentions that seeing is the ultimate source of wisdom. This means that intelligent observation serves as a cornerstone for the development of concepts, and eyes (seeing) constitute a significant part of the mind (Arnheim, 1989, my emphasis). In other words, students’ decoding visual images can instigate higher-level thinking activities in their minds, which might contain an affective attitude towards the images they are decoding. Such affective interpretations based on an improved understanding of visual texts, were often observed in the form of empathy and perspective taking in this current study.

Moreover, during the book club discussions where collaborative inquiries took place, the participants shared their views and their own narratives. With the use of homeplace positions, the participants constructed and interpreted life events. The picturebook provided the participants with vicarious experiences such as border-crossing and immigrants’ identity crises on foreign soil (McVee& Boyd, 2016). This vicarious exploration of possible stories, imagining the self in different situations, and comparing this to the current sense of self, can help the students examine ‘possible selves’ (McVee & Boyd, 2016, p. 41) and can provide the opportunities to nurture empathy and perspective taking. The open-ended nature of the book club discussions also helped the participants generate their own voices, which were heterogeneous due to their different personal experiences and viewpoints (Wertsch, 1991).

As seen in this present study, visual thinking with a multicultural picturebook and open-ended discussions can empower students of English. These activities provided them with the opportunities to jump into visual images, to be stimulated with tantalizing questions, and to extend their aesthetic understanding of the visual images in order to understand different aspects of the world. In other words, this study filled the gap in the understanding of ‘children and teenagers’ affective, aesthetic and wider educational needs in addition to their functional-communicative language learning needs’ (Bland, 2013, p. 5). Stories, including multicultural picturebooks, can ‘connect us to our innermost selves and [end of page 16] to one another in powerful ways that develop not only our sense of personal identity but also a sense of shared humanity and empathy’ (Parsons, 2016, p. 21). This sense of connectedness is where teaching English as a global language is destined to lead.

Bibliography

DiCamillo, K. (2006). The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane. New York, NY: Candlewick Press.

Say, A. (2009). Tea with Milk. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Tan, S. (2010). The Lost Thing. Sydney, Australia: Lothian Books.

References

Alter, G. (2018). Integrating postcolonial culture(s) into primary English language teaching. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 6 (1), 22-44.

Arizpe, E., & Styles, M. (2016). Children Reading Pictures: Interpreting Visual Texts. New York, NY: Routledge.

Arnheim, R. (1970). Visual Thinking. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Arnheim, R. (1989). Thoughts on Art Education. Santa Monica, CA: Getty Center for Education in the Arts.

Bae, J. (2012). Developing general literacy ability and intercultural sensitivity through English literacy instruction: Using global literature for Korean EFL learners. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), University of Kansas, Lawrence.

Bland, J. (2013). Children’s Literature and Learner Empowerment: Children and Teenagers in English Language Education. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Brooks, W., & Browne, S. (2012). Towards a culturally situated reader response theory. Children’s Literature in Education, 43: 74-85.

Brown, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

Burke, A., & Peterson, S. (2007). A multidisciplinary approach to literacy through picture books and drama. English Journal, 26 (3), 74-79.

Callow, J. (2017). “Nobody spoke like I did”: Picturebooks, critical literacy, and global contexts. The Reading Teacher, 71 (2), 231-237. [end of page 17]

Cho, J. H., & Kim, H. R. (2016). 포스트모던 그림책 활용 초등 영어 창의적 글쓰기 지도.

(Teaching of creative English writing in a primary EFL context using postmodern picture books). English 21, 29 (2), 283-307. Retrieved from http://www.english21.or.kr/

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review, 57 (3), 402-423.

Crawford, E. O., & Kirby, M. M. (2008). Fostering students’ global awareness: Technology applications in social studies teaching and learning. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 2(1). 56-73.

Dailey-O’Cain, J., & Liebscher, G. (Eds.) (2009). Teacher and Student Use of the First Language in Foreign Language Classroom Interaction: Functions and Applications. Bristol, U.K.: Multilingual Matters.

Feinberg, R. A., Mataro, L., & Burroughs, W. J. (1992). Clothing and social identity. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 11(1), 18-23.

Ghosn, K. I. (2002). Four good reasons to use literature in primary school ELT. ELT Journal, 56 (2), 172-178.

Hanvey, R. G. (1982). An attainable global perspective. Theory into Practice, 21(3). 162-167.

Hicks, D. (2003). Thirty years of global education: A reminder of key principles and precedents. Educational Review, 55(3), 265-275.

John-Steiner, V. P., & Meehan, T. M. (2000). Creativity and collaboration in knowledge construction. In C. D. Lee, & P. Smargorinsky (Eds.), Vygotskian Perspectives on Literacy Research. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, pp. 31-50.

Kaminski, A. (2013). From reading pictures to understanding a story in the foreign language. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 1, 19-38.

Kang, J. (2010). 다문화 영어 그림책을 활용한 어휘 관련 다문화 문식성 (Multicultural English Literacies) 교육: SIOP 모델 기반. A study on multicultural English literacy education related to vocabulary through multicultural English picture books: Based on SIOP model. Bilingual Research, 43, 1-28.

Kiefer, B. (2008). What is a picture book, anyway? The evolution of form and substance through the postmodern era and beyond. In L. R. Sipe & S. Pantaleo (Eds.), Postmodern Picture Books: Play, Parody, and Self-referentiality. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 9-21. [end of page 18]

Kim, H. & Kim, E. (2010). 다문화 아동문학 텍스트 기반 반응저널 쓰기를 통한 초등영어와 문화의 통합교육. (A study of integrating culture into elementary English through response journal writing based on children’s multicultural literature). Primary English Education, 16(2), 81-110.

Kirkwood, T. (2001). Our global age requires global education: Clarifying definitional ambiguities. Social Studies, 92, 1-16.

Kwon, H. J. & Kim, H. R. (2012). 패턴이 있는 이야기책 기반 초등영어 학습부진학생의 문자언어 지도에 관한 연구. (A study of teaching literacy to primary school English underachievers based on patterned storybooks). Foreign Languages Education, 19(2), 143-175.

McVee, M. B. & Boyd, F. B. (2016). Exploring Diversity through Multimodality, Narrative and Dialogue: A Framework for Teacher Reflection. New York: Routledge.

Merryfield, M. (2000). Why aren’t teachers being prepared to teach for diversity, equity, and global connectedness? A study of lived experiences in the making of multicultural and global educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 429-443.

Mourão, S. (2013). Response to the Lost Thing: Notes from a secondary classroom. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 1(1), 81-105.

Murphy, P. (2009). Using picture books to engage middle school students. Middle School Journal, 40(4), 102-109.

Nicholas, J. L. (2007). An exploration of the impact of picture book illustrations on the comprehension skills and vocabulary development of emergent readers. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

Nikolajeva, M. (2012). Reading other people’s minds through word and image. Children’s Literature in Education, 43(3), 273-291.

Nikolajeva, M. (2013). Picturebooks and emotional literacy. The Reading Teacher, 67(4), 249-254.

Park, E. (2011). 블렌디드 러닝 기반 영어동화학습을 통한 초등학교 4학년 읽기 능력 신장에 관한 연구. (The effects of instruction using stories in blended learning environment). English 21, 24(4), 261-287.

Parsons, L. (2016). Storytelling in global children’s literature: Its role in the lives of displaced child characters. Journal of Children’s Literature, 42(2), 19-27. [end of page 19]

Reisberg, M. (2008). Social/ecological caring with multicultural picturebooks: Placing pleasure in art education. A Journal of Issues and Research, 49(3), 251-267.

Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The Reader, the Text, the Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Rosenblatt, L. (1982). The literary transaction: Evocation and response. Theory into Practice, 21, 268-277.

Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the Visual: An Introduction to Teaching Multimodal Literacy. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Shin, J. W., & Kim, H. R. (2017). 그림책 전기를 활용한 장르중심 쓰기 기반 초등영어 문자언어 지도. (Teaching primary English literacy through genre-based writing using picture book biographies). English 21, 30 (3), 247-272. Retrieved from http://www.english21.or.kr/

van Leeuwen, T. (2011). The Language of Color: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the Mind: A Sociocultural Approach to Mediated Action. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wissman, K. (2019). Reading radiantly: Embracing the power of picturebooks to cultivate the social imagination. Bookbird, 57 (1), 14-25.

Wolfenbarger, C., & Sipe, L. R. (2007). A unique visual and literacy art form: Recent research on picture books. Language Arts, 84 (3), 273-280.

Yenawine, P. (2013). Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning across School Disciplines. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Yeom, E. Y. (2018). How Visual Thinking Strategies using picturebook images can improve Korean secondary EFL students’ L2 writing. English Teaching, 73(1), 23-47. Retrieved from http://journal.kate.or.kr/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/v73_1_02.pdf

Yoon, B., Yöl, O., Haag, C., & Simpson, A. (2018). Critical global literacies: A new instructional framework in the global era. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(2), 205-214. [end of page 20]