| Promoting Reading for In-Depth Learning for Critical Literacy and Interculturality

Sunny Man Chu Lau, Nayr Correia Ibrahim and France Destroismaisons |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This article describes and elaborates on the Reading for In-Depth Learning (Ridl) Framework (ELLiL Project Partners, 2023), co-developed by researchers from Nord University, Norway and Bishop’s University, Canada in a research partnership project, titled English Language and Literature – In-Depth Learning (https://site.nord.no/ellil/). Drawing on Bland’s (2022) deep-reading framework and Lau’s (2013) integrated critical literacy instructional model, the Ridl framework comprises four intersecting dimensions – textual, personal, critical and creative and transformative – that aim to facilitate teachers’ planning and design of learning activities based on the use of children’s and young adult (YA) literature (or any texts) to support language learning for critical literacies and interculturality. We will outline the Ridl framework’s theoretical grounding and illustrate its pedagogical application by elaborating on a unit plan based on the picturebook We are Water Protectors (2020) by Carole Lindstrom and illustrated by Michaela Goade.

Keywords: children’s literature, critical literacies, ELT, in-depth learning, reading for in-depth learning framework, transformative pedagogy

Sunny Man Chu Lau is Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) in Integrated Plurilingual Teaching and Learning, and Professor in the School of Education at Bishop’s University, Québec, Canada. She specializes in critical literacies, literature and language teaching, ELT, plurilingual pedagogy, and participative-based research methodologies.

Nayr Correia Ibrahim is Associate Professor of English Subject Pedagogy at Nord University, Norway, leader of the Nord Research Group for Children’s Literature in ELT and peer reviewer for Children’s Literature in English Language Education. Her research interests include bi/multilingualism, early language learning, multiple literacies, language and identity, learning to learn, children’s literature and children’s rights.

France Destroismaisons was a former ESL pedagogical consultant for the Centre de services scolaire de la Région-de-Sherbrooke and has been teaching ESL to 6- to 12-year-old students in Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada for 17 years. She integrates explicit reading and writing strategies in teaching literature for language learning. She collaborates with other homeroom teachers in her school on interdisciplinary projects to promote in-depth learning.

Introduction

The humanistic and educational value of teaching and learning of literature has been strongly promoted in language classrooms for cognitive and emotional development as well as responsible citizenship (Ellis & Brewster, 2014). Different literary formats, be they short stories, picturebooks, poems, or graphic novels, are used as pedagogic media through which learners can explore experiences vicariously through fictional characters or personae and reflect on their own and others’ values and circumstances as well as how different worldviews bear significance on their lives (Botelho, 2021). However, when it comes to English as a second language (ESL) classrooms, there is often a lack of focus on the informed use of literature for language teaching. Initial ESL teacher education is often designed by applied linguists who prioritize curricular focus on discrete language structures and use (Bland, 2018). There is also a dominant deficit-oriented perception of English language learners as less capable readers, which deters teachers from using literature in their classrooms (Lau, 2013). When they do, they often find themselves ill-prepared and lacking in pedagogical resources to engage their learners in meaningful ways for both language learning and critical discussions.

To provide pedagogical support for teachers, this article aims to describe and elaborate on the Reading for In-Depth Learning (Ridl) Framework (ELLiL Project Partners, 2023), co-developed by researchersi from Nord University, Norway and Bishop’s University, Canada in a research partnership project, titled English Language and Literature – In-Depth Learning (https://site.nord.no/ellil/)ii. The four-year project aimed to promote teachers’ use of children’s and YA literature in ESL classrooms and involved a semester-long exchange for student teachers in the respective universities and a weekly practicum experience in a local school each year, under the mentorship of a local ESL teacher. The dyads also worked closely with the research team members in the respective sites to co-develop and implement unit plans using the Ridl framework. The overall goal was to promote teachers’ agency and creativity in using literature in ESL classrooms and to foster critical language practices that enhance an awareness of oneself in the world, respect for linguistic and cultural diversity, and a sense of responsibility for others (Parekh, 2003). In this paper, we describe the Ridl framework and its theoretical grounding, then illustrate its pedagogical application by elaborating on a unit plan based on the picturebook We are Water Protectors (2020) by Carole Lindstrom, illustrated by Michaela Goade.

The Reading for In-Depth Learning (Ridl) Framework

In-depth learning

The Ridl framework (Figure 1) was developed to support teachers when engaging with literary texts in the ESL classroom. The framework supports the development of deep reading for in-depth learning, centring literature as a gateway to creative, socially relevant education. In-depth learning is described by Fullan, Gardner and Drummy (2019) as ‘learning that helps [students] make connections to the world, to think critically, work collaboratively, empathize with others, and, most of all, be ready to confront the huge challenges that the world is leaving their generation’ (p. 66). Three main themes emerge as key elements for operationalizing in-depth learning in, and beyond the classroom: connectedness, empathy and critical thinking. Bland (2022) describes ‘connectedness’ as a central notion of in-depth learning as ‘connecting across school subjects, learning through cross-curricular topics such as global issues, interculturality and diversity competence, creates opportunities to expand subject knowledge and support the transfer of learning beyond school’ (p. 25). Connecting at a personal level entails emotional engagement with the plight of the Other, close or distant, hence the development of empathy, an indispensable social skill with global repercussions for social transformation. Underlying these connections is the critical dimension that requires both intellectual and emotional self-reflexivity (Lau, 2013), metacognitive agility and thoughtful engagement with historical and contemporary diversity.

Development of the Ridl framework for the ESL classroom

Adapted to the ESL classroom, the framework provides a tool through which to support teachers’ engagement and experimentation with the interconnected dimensions of in-depth learning. Often, in ESL or other second language classrooms, comprehension remains on the surface-level of understanding vocabulary or grammar usage rather than on learning and using the language to make meaning and reflect on matters and issues that have significant social consequences on the students’ lives. To achieve in-depth understanding, students are required to think critically about the topic, analysing and evaluating meaningfully the impact of the written text in the real world (Luke, 2019). It also entails a true appreciation of what they are reading and connecting personally to the message which promotes personal development and change (Botelho, 2021). The framework provides support for the reader to engage in critical multicultural analysis as a multifaceted ‘midwife of meaning’ (Botelho & Rudman, 2009, p. 4) locating the social, political, textual and linguistic power dynamics exercised in the text. In turn, the students become ‘border-crossers [as they learn] to read and write as part of the process of becoming conscious of one’s experience as historically constructed within specific power relations’ (Anderson & Irvine, 1993, p. 82).

According to Bland (2022), the reader develops the abilities to consider different perspectives and to comprehend others’ feelings and attitudes by exploring real-world topics vicariously through the characters in stories. Hence, in-depth understanding is not limited to cognitive activity, but is also embodied, affective comprehension that stimulates empathetic insight, creativity, and interculturally responsive actions. Engaging students with literature in language learning can support in-depth learning, as Bland (2022) astutely puts it, ‘[d]eep reading of worthwhile narrative supports engagement through experiencing problems vicariously, together with the protagonist, and real-world topics explored through story can be an excellent contribution to in-depth learning’ (p. 42). Pedagogical frameworks and models ‘for effective practice provide a template for curriculum development, materials creation and collaborative active learning, together with expert support in the context of professional development and through systematic reflection, experimentation and further reflection on learning’ (Ibrahim & Mourão, forthcoming).

The Ridl framework is based on two existing models for developing in-depth learning with literature:

- Bland’s (2022) deep-reading framework, consisting of ‘four interweaving steps as a suggested guiding structure for the exploration of literary texts and their affordances for educational goals’ (p. 25). These four steps are Unpuzzle and Explore, Activate and Investigate, Critically Engage and Experiment with Creative Response. The idea is to ‘activate’ the reader’s prior knowledge as key to a personal engagement with the text and to critically and creatively ‘investigate’ the links between the text, the reader and the world.

- Lau’s (2013) integrated critical literacy instructional model, ‘embracing a greater degree of self-reflexivity and a balance between affective and intellectual engagements to ensure a deeper reflection of one’s tacit beliefs, better self-awareness and critical understanding of social realities’ (p. 7). Building on various critical literacies frameworks (e.g., Freebody & Luke, 1990; Janks 2000, 2010; Lewison et al., 2008), Lau’s model comprises four intersecting dimensions – textual, personal, critical and creative and transformative – which form the basis for the Ridl Framework.

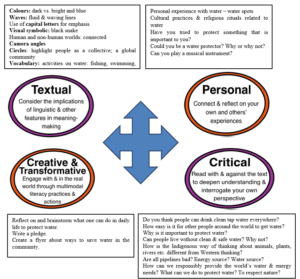

Figure 1. The Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework.

The similarities in focus of these structured approaches provide a basis for the Ridl framework that supports teachers’ planning around a literary text and students’ engagement with literature for developing critical global citizenship (Lourenço, 2021). Neither Bland’s framework, nor Lau’s model proposes a strict chronological order in addressing the different dimensions, thus allowing for teacher agency in how to explore the text. However, both seem to indicate an initial engagement with the literary/stylistic, linguistic and visual dimensions of the text. This textual-visual ensemble (Ibrahim, 2022; i.e., analyzing both the textual and visual narratives), provides a multimodal entry to the text, creating a literary space for developing students’ knowledge of textual features and their contribution to meaning-making. Critical and creative responses round off the two models, encouraging the action-taking and transformative practice.

The Ridl framework consists of four dimensions – textual, personal, critical and creative and transformative – summarized by the four circles on the right. The heart-shaped figure captures the pedagogical focuses of each dimension, elaborating on their key teaching and learning activities. The central circle underscores the importance of selecting texts that are cognitively, affectively, and socially appropriate for critical learning in the classroom.

The textual dimension. This dimension articulates an overt focus on students’ learning of the linguistic structures as well as the multimodal design features in reading all text types. Often language forms, whether grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary or syntax, are the first, and sometimes sadly the only, aspects of a text that ESL teachers would focus on. However, as communication is fundamentally multimodal, it is important to support students’ understanding of how language functions in conjunction with other modalities, particularly how they are deployed together to construct a certain message and a certain reader position to shape the way we think and/or feel about the message.

The critical dimension. This dimension engages students in investigating how the text positions them as readers. Analyzing the multimodal textual features and use of language and stylistic devices also enables students to find and interpret gaps and ambiguities. It is important that these critical analyses are not done in a detached manner as if those issues were other people’s problems. This takes us to the personal dimension.

The personal dimension. Students should be invited to make personal connections to the social issues addressed in the texts in this dimension. This is not only to activate their prior knowledge on the subject matter, but also to encourage them to make text-to-self, text-to-text, and text-to-world connections in order to share and examine more carefully what they are thinking and feeling about these real-life issues and how they are (or not) personally and emotionally invested in them. This invites their unique voices and promotes self-awareness. As Bland (2022) argues, ‘in-depth learning increases when students recognize the relevance of their learning for life outside of school, and their own contributions become an important part of the fabric of the lesson so that they are keen to invest in their learning’ (p. 27). Hearing their classmates’ different personal connections and perspectives can also foster a better understanding of the different cultural lenses through which students interpret and make sense of the text. Engaging with the emotional resonances of the story allows ‘the cultural, literary and language input to become more memorable’ (Bland, 2022, p. 24). This supports the recognition of and respect for diverse worldviews and the understanding of the sociocultural and political conditions that shape those values and beliefs.

The creative and transformative dimension. Finally, in this dimension, we engage students in taking action to address the issues discussed through creative and constructive means. Transformation here refers to actions children can take to make a difference in their lives or immediate environment, not necessarily on a grand scale. This goal is to invite students’ application of their learning to critically reflect and act on real world issues through a variety of multimodal literacy practices and actions, whether through visual art, video production or concrete acts that go beyond the classroom.

Text selection: The Head-Hands-Heart approach

The Ridl framework is completed with a focus on text selection based on the Head-Hands-Heart (H-H-H) model for transformative practice (Singleton, 2015). The H-H-H model constitutes a holistic approach to educational practice relating the cognitive domain (Head) to critical reflection, the affective domain (Heart) to relational knowing, and the psychomotor domain (Hands) to engagement and action taking. The H-H-H model has been implemented in various aspects of educational practice, for example for reflecting and reviewing on learning through picturebooks (Alferink & Ibrahim, 2022) in the ICEPELL project (ICEPELL Consortium, 2022), and for sustainable education (Singleton, 2015), both with a strong focus on action in the community.

Selecting a compelling text in terms of language, theme, and visuals is key to supporting students’ engagement with literature. Hence, the inclusion of an explicit text selection dimension is a fundamental step in supporting teachers and students’ enjoyment of the text. The tripartite H-H-H model can be understood in the following way:

- Head links to critical reflection and focuses on the thinking and learning processes, thus enabling teachers and students to make decisions on aspects of the text such as, language difficulty, cognitive challenge and conceptual challenge;

- Heart links to the affective domain and asks teachers and learners to reflect on how they feel about the themes or characters in the text and how they will be able to motivate students to engage affectively with the text;

- Hands links to taking action, encouraging the teachers and learners to think of a concrete action that they can implement in response to a global or social issue highlighted in the text.

Based on previous experiences, the ICEPELL project, for example, claims scaffolding teachers’ selection of an appropriate text necessitates ‘a proactive and concerted decision to plan for an action-oriented approach to English language education’ (Ibrahim & Mourão, forthcoming). According to Valente (2024), text selection needs to be compelling for the ages and life stages, have resonance with the lived experiences of the learners and requires a level of challenge (cognitive, affective, social), counterbalanced by sufficient scaffolding in planning and in the classroom. In this sense, the Ridl framework provides scaffolding that can support critical learning, not only in ESL classrooms but also any first or second language classrooms, and across age levels, including tertiary. In the following section, we will explore the role of the Ridl framework for unlocking the potential of texts in the English language classroom, by analyzing a unit of work in the Canadian context.

A Sample Unit Plan Using the Ridl Framework

To illustrate how the Ridl framework works, we elaborate on a unit plan that the research team co-developed with a Grade 6 ESL mentor teacher, co-author of this paper France Destroismaisons, from a Quebec elementary school (ages 6-11) and her mentee, a student teacher from Norway who was on a four-month international placement as part of the ELLiL Project. The medium of instruction in this school is French, and it offers an enriched ESL program, meaning students have 2.5 hours of ESL classes a week (rather than the one-hour-per-week regular ESL programme). Students in this school were mostly locally born francophones, and the teacher might occasionally have one to two students with immigrant backgrounds. Using the Head-Heart-Hands approach, the picturebook We are Water Protectors (Lindstrom & Goade, 2020) was selected to engage children with issues about water protection (Head), with their connectivity with the natural environment (Heart), and with exploring ways to effect change (Hands). The story talks about a girl who rallies support to defend the clean water supply in her community against the threat of the pipeline that is presented metaphorically as a ‘snake’ in the book. The story was inspired by Indigenous people-led movements across North America who gathered efforts against the Dakota Access Pipelines to safeguard water from harm and corruption. In the next sections, we will describe the process of how teachers can use the four dimensions of the Ridl framework to brainstorm learning activities, identify the ‘Big Ideas’ to then sequence these activities to scaffold students’ learning through literature.

Brainstorming teaching ideas

The team in Quebec first brainstormed teaching ideas relating to each of the textual, personal, critical and creative and transformative dimensions (see Figure 2). For example, in the textual dimension, the use of colours (e.g., dark and light blue) and fluid and wavy lines (of the water) throughout the book is key in highlighting the connected and organic nature of entities in the environment, such as the sky, land and ocean as well as human, animals and all things around us. The use of circles (e.g., the moon, the sun, and the human circle formed by leaders from different Indigenous communities) also foregrounds the strength in working together in harmony. As for the personal dimension, it is imperative to start with what students already know. Here, for example, we can start with inviting students to share their personal experiences with water such as the water sports they enjoy, or cultural or religious ceremonies associated with water that they know of, or practice. Connecting to the theme of water protection, we can also invite students to reflect on whether they have ever been moved by a cause and tried to protect something important to them. Another possibility is to ask them if they play an instrument, because in the story the community leaders gather and play music.

Figure 2. Brainstorming teaching ideas for We are Water Protectors using the Ridl framework.

At this brainstorming stage, we would like to exhaust all teaching possibilities afforded in the chosen text. This does not mean that we will or should do each and every activity we can think of. However, having an exhaustive list of teaching and learning ideas will allow us to begin to see the scope that the unit can cover and what should be focused on to better address students’ needs and concerns (both content and language wise). For example, when we brainstorm ideas for the critical dimension, we think of questions to help students to think with and against the text: ‘Are all pipelines bad?’ and ‘How can we responsibly provide the world’s water and energy needs?’. These questions are important because there are many people arguing for and against pipelines, and respective arguments from either side continue to fuel contention. While supporters argue that pipelines can reduce congestion and gas emissions from road, rail or shipping transportation networks, those who are against underscore the risks of any pipeline leakage or spillage which will contaminate the water supply and cause irreversible damage to the animals and peoples in their paths, endangering the ecosystem and communities, particularly Indigenous sacred sites (Perls, 2024). However, considering that it was this Grade 6 class’s first encounter with the topic, Destroismaisons preferred to focus more on raising awareness about the need to protect water and ways individual students can create change. The controversies about the pipelines could be explored at a later stage, possibly within an interdisciplinary approach, in collaboration with the Social Studies teacher. Similarly, for the creative and transformative dimension, there could be many interesting multimodal literacy practices and actions students can take after reading the story. However, given the time constraints, we need to consider which culminating task(s) best enable(s) students to reinvest or re-apply what they have learned, in terms of both language and concepts. In this case, the writing of a pledge (which is based on the last page of the book) and producing a flyer about ways they and their peers can save water in the community will better address the goals (both activities were inspired by ICEKit#17 [Bento et al., 2022]; see section on key learning activities for more).

Getting down to the ‘Big Ideas’ and lesson sequencing

Following the brainstorming stage is an important step of identifying the ‘Big Ideas’. Big ideas are the pedagogical purposes that drive the planning and teaching within a unit and/or across units (Mitchell et al., 2017). They help to provide coherence for all teaching and learning activities and help both teachers and students understand why they are doing what they are doing. As teacher educators, we have seen activities done in class that are merely remotely connected to the overarching learning goals, and sometimes even if the learning activities were relevant, students were not aware of the pedagogical purpose behind the tasks. The big ideas can help define the scope of the unit(s) and ensure coherence and meaning across the learning activities. In this case, our big idea for this unit was:

Examine and reflect on one’s role in protecting the natural environment, both human and non-human, and daily-life actions one can take to protect water.

This, of course, does not mean that teachers cannot change and adapt the activities based on students’ ongoing reactions or responses in class. To meet students’ emerging needs, some activities might need to be adjusted, which could lead to a slight modification of the big ideas as the unit moves along. No matter what the shifts are, a coherent purpose should always be present throughout all learning activities.

Once the Big Ideas are set, the next step is to select those learning activities that are most pertinent to the pedagogical purpose, and then sequence them in a logical manner so that at each step, students are building their learning in a spiral and progressive way, i.e., learning new ideas or skills while revisiting or reinvesting what has been learned (see Appendix 1 for the full lesson sequence with learning activities for students)iii. Below we highlight some key learning activities to illustrate how the four dimensions (textual, critical, personal, and creative and transformative) intersect and unfold in the classroom, ending with two final culminating tasks/outcomes.

Key learning activities for We are Water Protectors

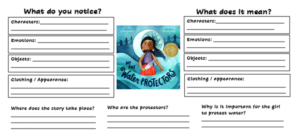

Before reading the story, key vocabulary is introduced through a word-to-picture matching activity, words such as snake, waterfall, feather, drum, etc. (textual) (Learning Activity 1; see Appendix for the full unit plan). What follows is an exploration of the book cover and title (Learning Activity 2). For any visuals, we like to structure the discussions based on these two main questions: What do you notice? and What does it mean? (see Figure 3). The idea is to get students to pinpoint the specific visual elements that they notice and think about the meaning they can create. We apply the same two questions to all key pictures read and discussed in class to get students used to always finding evidence (visual or textual) to support their ideas or arguments (textual dimension).

Figure 3. Learning activity 2 – Book cover.

Teachers can invite students to share what they notice in an illustration and then share what they think it means within the context of the book. Alternatively, teachers can also provide some sub-categories, such as characters, emotions, objects and clothing/appearance as shown in Figure 3, to further scaffold students’ close reading of the visuals. The sub-categories here help students to make inferences about where the story takes place, who the protectors might be, and why it is important for them to protect water. These questions also support students in understanding how multimodal features are deployed to construct meaning (textual dimension) and evoke emotions to impact their affective understanding of the story (personal dimension).

It may not always be possible to ponder every illustration with the class. Therefore, it is important to plan ahead which illustrations to focus on so as to best support students’ deep understanding of the text. In We are Water Protectors, the spreads that show the main character’s relationships with her ancestors and the water/natural environment, the impending danger posed by the pipeline/snake, and the gathering of support from the community are some important pages to ponder and discuss (see learning activities 3, 5 & 6 in Appendix). Reading the visuals in conjunction with the text will help students better relate (both cognitively and emotionally) to the threat faced by the main character and her community (personal and critical dimensions) and what individuals can do to make a difference (creative and transformative dimension).

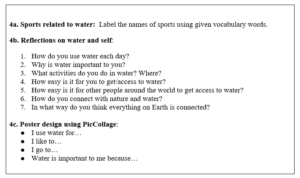

To further support students’ emotional connections with water, an activity on Water and Me (Table 1) is used to prompt their reflections. The activity starts with a labelling exercise whereby students name pictures of various water sports by using the vocabulary provided, such as canoeing, swimming, water skiing, snorkelling, etc. This helps them to see how we all depend on water, not only for drinking but also for many other leisure activities (personal dimension). The follow-up discussion questions prompt them to critically reflect on the importance of water to our individual and collective lives and begin to question if people around the world have equal access to water (critical dimension).

Table 1. Learning activity 4 – Water and me.

These reflections prepare students for the next activity whereby they use PicCollage to create a poster that illustrates their relationship with and appreciation for water (textual, personal and critical dimensions). Here are some work samples from Destroismaisons’ Grade 6 ESL class:

Figure 4. Students’ Water and Me posters.

The creative and transformative dimension is key to any in-depth learning as it mobilizes students to reinvest their understanding and learning into taking real-life actions to effect change. In this story, the protagonist, despite her young age, takes proactive actions to gather support from her community to start a water protection movement. To connect the story with real world events, two examples are drawn on for the students to see how young children can create change in their own ways (personal and critical dimensions). The first one is a video about Tokata Iron Eyes, a 13-year-old Indigenous girl who united different Indigenous tribes and non-Indigenous people from across the United States to stand up against the Dakota Access pipeline. Tokata articulates a clear message about water protection in the video: ‘This is not just for us. It is a wake-up call for everyone. Everyone needs water to live’ (see learning activity 7 in Appendix).

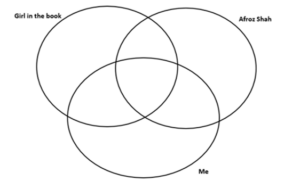

The second video is a documentary about Afroz Shah who initiated and led a beach clean-up movement in Mumbai and was awarded the United Nations’ 2016 Champion of the Earth title. The video-watching is scaffolded by the Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How questions for comprehension (textual dimension). This is followed by a compare-and-contrast activity (Figure 5) in order for the students to reflect more deeply on how they individually are similar to or different from the two young environmental activists in the ways they relate to the environment and the actions they have taken (or not) in protecting the earth (critical and personal dimensions).

Figure 5. Learning activity 7d – Compare and contrast.

This paves the way for the final two culminating tasks/outcomes. The first one is an earth steward and water protector pledge, which is based on the final page of the book, and students just need to sign the pledge (see learning activities 8 a-c in Appendix). However, they can always create their own version to better reflect what they intend to work on after reading the book. To prepare for this task, teachers can brainstorm ideas from daily life that can help reduce water wastage and pollution and safeguard its cleanliness and accessibility. Figure 6 shows some students’ earth steward and water protector pledge from Destroismaisons’ class.

Figure 6. Samples of students’ earth steward and water protector pledges.

The pledge also lays the groundwork for the second culminating task/outcome – designing a ‘Be a water protector’ poster (see learning activity 8d in Appendix), to remind their peers about the importance of water to all humans and non-humans and our responsibility for water protection. In designing the poster, students can get to reinvest their learning of multimodal design features, including the employment of both visual and textual features to put forward an eye-catching and convincing message (textual dimension) and give concrete actionable suggestions for their peers to effect change in their environment (personal, creative, and creative/ transformative dimensions).

Figure 7. Examples of students’ designs for ‘Be a water protector’ posters.

Discussion and Conclusions

To conclude, we would like to share some of Destroismaisons’ reflections on her experience in using the Ridl framework for lesson planning and design. Her comments reflect a positive impact of the framework on her teaching with literature in her Grade 6 class. For example, she found that the framework helped to take her teaching further with a ‘more complete’ planning, as she explained:

Usually, we tend to focus on analysis of the text components. We do the final task that is kind of engaging [our students] a little, but not in depth. All that connection to the text and the critical aspect, not that it’s rare, but we tend to skip them because of time.

She found that integrating the four dimensions has afforded more opportunities for her students to ‘reinvest what they already know, but in English’. It has pushed her students, and herself as well, ‘to focus on the connection and the critical aspect’ that have seldom been practised in her class. The creative and transformative dimension has also pushed her to think of ‘activities in more depth to make sure that we really engage them in the community that will have an impact’ and that ‘they’re doing something with what they’ve learned and they’re kind of helping others to become more conscious of that universal theme that we’re working on with the book’. Furthermore, the focus on ‘What do I notice?’ and ‘What do they mean?’ really supported students’ analyses of the visuals and they were able to ‘turn the pages and look at the pictures in more depth’ and ‘bring meaning to the pictures and connect to what the author wanted to say’. Through repeated practice of finding visual (and textual) evidence to support ideas, Destroismaisons found that her students were getting better in looking for meaning beyond the surface level. As she explained:

…students were able to connect personally, locally, and also regionally. […] They now know where North Dakota is, where Alaska is. And so, they better understood the reality of the Indigenous people with the environmental issues that they have.

Students also made connections with an environmental issue in the eastern Quebec region where they lived. It had been just over a decade previously when a train carrying crude oil tanks derailed in a nearby town Lac-Mégantic, resulting in an explosion that had caused many deaths and injuries and the destruction of the town (Duggan, 2023). Many students connected this with the pipeline in the story, showing an understanding of its potential danger to Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities alike. In sum, for Destroismaisons, the Ridl framework ‘is pinpointing some elements that [she] was not doing’ but now she has been ‘trying to do more and more’ as she plans her lessons. She also added that no matter how well designed a unit plan is based on the framework, one still has to adapt and modify the learning activities based on the ‘students in front of us’, their cultural backgrounds, language levels or emotional capacity and readiness.

The impact of the Ridl framework is undeniably significant for Destroismaisons’ personal and pedagogical development. However, as creative as the two final culminating tasks are, it has not been easy to take them beyond the classroom. Students did reflect on what they could do individually to save water and understand the potential danger of pipelines. Destroismaisons also printed out her students’ Be a Water Protector posters and had them displayed in the school during one of the hallway gatherings for the community (something like a school open day). Apart from these, there was no follow-up on whether the students did take up the pledge in any concrete ways in their daily life, nor was there any concrete movement or campaign within the school or the community to appeal to a real audience for change. It is indeed not always easy to engage students in activities in the creative and transformative dimension that take them beyond the cognitive (head) aspect to becoming action-taking, embodied learning opportunities (heart and hands) outside of the classroom walls. Teachers need further support on transforming the message in these literary texts into purposeful actions in the local-global communities to foster in-depth learning. This might also require an interdisciplinary approach with collaboration from other subject teachers to support learning and doing in the communities.

Furthermore, although having the critical dimension does invite teachers to pose questions to prompt students’ critical reflections on current social issues, based on the ELLiL Project teacher educators’ observations of other teachers using the framework, we found that the class discussions are limited in scope. Teachers still tend to pose closed questions and move on quickly to the next when a student gives the ‘correct’ answer they are looking for. However, the critical discussions are not about finding the right answers but rather supporting students to reflect and think deeply, consider various ideas and weigh different perspectives. Perhaps teachers feel pressured to reassure children with the ‘right’ answers, yet children need to learn that sometimes there is no right answer. The Ridl framework may not be a panacea; however as experienced by Destroismaisons, the framework as enacted in the classroom does serve as a ‘midwife’, providing the needed assistance to support the teacher’s reflection and planning and the students’ meaning construction processes.

Bibliography

Lindstrom, Carole, illus. Michaela Goade (2020). We are Water Protectors. Roaring Brook Press.

References

Alferink, M., & Ibrahim, N. C. (2022). Reflecting and reviewing. In ICEPELL Consortium (Eds.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 47–54). CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

Anderson, G., & Irvine, P. (1993). Informing critical literacy with ethnography. In C. Lankshear, & P. McLaren (Eds.), Critical literacy: Politics, praxis, and the postmodern (pp. 81–104). SUNY Press.

Bento, C., Bonelli, M., Neufeldt, A., & Sprenkels, T. (2022). ICEKit#17 We are water protectors. In ICEPELL Consortium (Eds.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 47–54). CETAPS, NOVA FCSH. https://icepell.eu/Kits/ICEKit17_We_are_water_protectors.pdf

Bland, J. (2018). Introduction: The challenge of literature. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8-18 year olds (pp. 1–22). Bloomsbury Academic.

Bland, J. (2022). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury.

Botelho, M. J., & Rudman, M. K. (2009). Critical multicultural analysis of children’s literature: Mirrors windows, and doors. Routledge.

Botelho, M. J. (2021). Reframing mirrors, windows, and doors: A critical analysis of the metaphors for multicultural children’s literature. Journal of Children’s Literature, 47(1), 119–126.

Dallaire, L. (2021) Learning and evaluation situation ‘Doing good together’. Centre de services scolaire de la Rivière-du-Nord. https://sites.google.com/csrdn.qc.ca/specialtoolbox/high-school/doing-good-together

Duggan, G. (2023, July 6). What we’ve got on the tracks today are bombs. Many residents say Lac-Mégantic was only a matter of time. CBC Docs. https://www.cbc.ca/documentaries/what-we-ve-got-on-the-tracks-today-are-bombs-many-residents-say-lac-me-gantic-was-only-a-matter-of-time-1.6897798

ELLiL Project Partners. (2023). Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework. English Language and Literature – In-Depth Learning. https://site.nord.no/ellil/reading-for-in-depth-learning/

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2014). Tell it again! The storytelling handbook for primary teachers (3rd ed.). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/tell-it-again-storytelling-handbook-primaryenglish-language-teachers

Fullan, M., Gardner, M., & Drummy, M. (2019). Going deeper. Educational Leadership, 76(8), 64–69.

Ibrahim, N. C., & Mourão, S. (forthcoming). Linguistic, intercultural and citizenship objectives in early language learning: Picturebook selection for democratic citizenship. In S. Frisch, & K. Glaser (Eds.), Early language learning in instructed contexts: Current issues and empirical insights into teaching additional languages in primary school. Multilingual Matters.

Ibrahim, N. C. (2022). Examining a Northern Sámi-Norwegian dual language picturebook in English language education through a critical translingual-transcultural lens. Intercultural Communication Education, 5(3), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.29140/ice.v5n3.847

ICEPELL Consortium. (Eds.) (2022). The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning. CETAPS, NOVA FCSH.

Janks, H. (2000). Domination, access, diversity and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educational Review, 52(2), 175–186.

Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. Taylor & Francis.

Lau, S. M-C. (2013). A study of critical literacy work with beginning English language learners: An integrated approach. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 10(1), 1–30.

Lewison, M., Leland, C., & Harste, J. C. (2008). Creating critical classrooms: K-8 reading and writing with an edge. Routledge.

Lourenço, M. (2021). From caterpillars to butterflies: Exploring preservice teachers’ transformations while navigating global citizenship education. Frontiers in Education, 6, Article 651250, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.651250

Luke, A. (2019). Regrounding critical literacy: Representation, facts, and reality. In D. E. Alvermann, N. J. Unrau, M. Sailors, & R. B. Ruddell (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of literacy (pp. 554–574). Routledge.

Freebody, P. & Luke, A. (1990). Literacies programs: Debates and demands in cultural context. Prospect, 5(3), 85–94.

Mitchell, I., Keast, S., Panizzon, D., & Mitchell, J. (2017). Using ‘big ideas’ to enhance teaching and student learning. Teachers and Teaching, 23(5), 596–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1218328

Parekh, B. (2003). Cosmopolitanism and global citizenship. Review of International Studies, 29, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210503000019

Perls, H. (2024, October 14). The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). Environmental & Energy Law Program, Harvard Law School. https://eelp.law.harvard.edu/tracker/dakota-access-pipeline/

Singleton, J. (2015). Head, heart and hands model for transformative learning: Place as context for changing sustainability values. Journal of Sustainability Education, 9, 1–16.

Valente, D. (2024, August 11–16). Reading for in-depth learning within the English practicum – A partnership model for school and university [Conference presentation]. AILA Congress 2024, Malaysia.

Endnotes

i Janice Bland, Nayr Ibrahim and David Valente (from Nord University) and Sunny Lau and Wendy

King (from Bishop’s University).

ii The project was funded by HK-Dir – the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills,

which aims to support internationalization of higher education for knowledge exchange and

mobilization.

iii The learning activities are inspired by ICEKit#17 (Bento et al., 2022) and the Learning and

Evaluation Situation Doing Good Together (Dallaire, 2021).

Please download the PDF of the article to access the Appendix.