| ‘Who controls the past controls the future’ Benefits and Challenges of Teaching Young Adult Dystopian FictionLuisa Alfes, Joel Guttke, Annetta Carolina Lipari & Eva Wilden |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Contemporary society encounters enormous effects of technological developments, digital transformations, and scientific advances. In light of this, it is increasingly important to raise awareness of and deal with developments that affect the present and the future. One way of dealing with these advancements is through the field of young adult (YA) dystopian fiction that exaggerates current negative developments in order to highlight possible progressions within a society. Therefore, the introduction and analysis of YA dystopian fiction carries enormous potential for foreign language learners and should be considered from an educational perspective. This contribution describes YA dystopian fictions’ role and presents its potential in English language teaching (ELT). Further, this paper addresses the challenges and benefits of teaching dystopian fiction. It takes practitioners’ perspectives into account who have first-hand teaching experience with YA dystopian fiction. It does so by presenting findings of an interview study investigating secondary teachers’ opinions on and experiences with teaching YA dystopian narratives in German schools. As part of this study, the participants touched upon challenges relating to (1) the choice of dystopian texts and teaching resources, (2) text accessibility, (3) the versatility of teaching literature and (4) the relevance of policy documents in ELT. The findings indicate that teaching YA dystopian fiction poses a complex challenge to English teachers.

Keywords: YA fiction; dystopian narratives; meaningful texts; interview study; content analysis

Luisa Alfes (PhD) is currently teaching English as a Foreign Language education with a special focus on the value of literature and culture in the foreign-language classroom at University of Duisburg-Essen. She is further interested in combining her two subjects, EFL and Fine Arts, which she taught at secondary level.

Joel Guttke is a research assistant in ELT at the University of Duisburg-Essen. His empirical research revolves around teachers’ diagnostic competence and inclusive EFL education, focusing on academic underachievement, instructional quality, and students on the autism spectrum.

Annetta Carolina Lipari is a teacher of English and French as a foreign language at a Gymnasium (secondary school) in Düsseldorf, Germany. She completed her M.Ed. with a thesis on utopian and dystopian literature in the secondary EFL classroom at the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Eva Wilden is Professor of English at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Her research interests include empirical research on primary and secondary EFL education, inclusive foreign language education, culture and language education, digitalization and language learning as well as EFL teacher education.

Introduction

In Nineteen Eighty-Four (Orwell, 1949), the Party slogan asserts ‘Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past’. Perhaps Orwell is suggesting that it is crucial to understand how power constructs what we conceive as the past and how the past defines our future. Humanity has always been interested in what the future might entail. That is conceivably one reason why YA dystopian narratives enjoy immense popularity; they have been ‘a major part of the literary landscape for the best part of the century’ (Bland, 2018, p. 175). YA fiction dominates international bestselling lists (Alter, 2019), such as The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins (2008), which focuses on the fight against poverty in the post-apocalyptic nation of Panem in the annual Hunger Games, or The Circle by Dave Eggers (2014), which deals with futuristic perspectives of media control and online identities. Literature and films illustrating future scenarios are readily available across the globe and offer diverse topics and themes of ‘Scary New World[s]’ (Green, 2008).

Defining YA Dystopian Fiction Today

The current relevance given to and the increasing importance of YA dystopian fiction corresponds to a large variety of literary works. Even though YA dystopian fiction resists a concise definition, the genre is associated with certain key characteristics. YA fiction provides their readers with ‘a window through which they can view their world and which will help them to grow and to understand themselves and their role in society’ (Young Adult Library Services Association, 1996, quoted in Bucher & Hinton, 2010, p. 4). In addition, dystopian texts deal with topics and themes to frighten and warn their readers about possible bleak futures. Thomas More’s Utopia in 1516 was the origin of this literary genre, and is about an ideal human society on a fictional island. On the other hand, ‘dystopia’ is regarded as the ‘dark side of utopia – dystopian accounts of places worse than the ones we live in’ (Baccolini & Moylan, 2003, p. 1).

These terms – utopia and dystopia – were not widely used until the twentieth century, when Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932), Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1953) appeared. These deal with causes of genetic engineering, the consequences of governmental surveillance, or a society that is prohibited from preserving and reading books. Bland refers to them as the ‘classics’ of the dystopian literary landscape which, in her mind, are still relevant and urgent today (2018, p. 175). Matz, however, points out that there have been numerous developments in the field of futuristic fears because the ‘pressing (global) concerns tend not to remain the same’ (2019, p. 63). For example, a frequent characteristic of YA dystopias is to reconsider complicated relationships between humans and nature or technology, or both (Kleofastova et al., 2020, p. 106). The above-mentioned dystopian narratives represent perspectives from times when each novel was written. Some of the depicted topics might be ‘out-dated now, in the light of what science has achieved ever since’ (Matz, 2015, p. 268) and others ‘can be read alongside the plethora of more recent dystopias’ (Bland, 2018, p. 175).

Aims and Concepts of Teaching YA Dystopian Fiction

YA dystopian texts offer manifold opportunities for language teachers and learners. First of all, the question of whether and why YA fiction should or should not be taught in language education ‘has been asked over and again in the light of changing educational and sociocultural demands’ (Delanoy, 2018, p. 144). For the proponents of using literature in class, reasons are as abundant as the works themselves. YA texts are appropriate in age and content and hold a high potential for accessibility, one reason that makes working with YA literary texts motivating and profitable in the language classroom (Caspari, 2007, p. 11). They can provide valuable resources for students for their personal development. Hence, they serve as meaningful input for students on two levels: they have a communicative purpose which opens up manifold opportunities to discuss themes in class, and they are learner-centered, as they offer not only a shift of perspectives when learners empathize with the characters but sometimes also enable escapes from reality into fictional worlds.

More specifically, YA dystopian texts model the future and provoke their readers (Kleofastova et al., 2020, p. 105). They ‘examine society’s problems and inequalities through a (usually) claustrophobic lens’ (Zielinski, 2020). Bland gives additional reasons to teach dystopian texts in the foreign language classroom. She states that today’s popular culture ‘points to bewilderment and lack of trust in authority; consequently education must bestow a stronger confidence that students themselves are fit and able to make necessary changes’ (2018, p. 177) and that dystopian texts serve as valuable resources to carry out said changes. YA dystopias can help their readers examine society’s problems and provide students with ideas for making the world a better place. Bland, for example, suggests reading The Hunger Games in class to embrace ‘the advantage it gives students who probably know aspects of popular culture of the twenty-first century better than their teachers’ (2018, p. 177, italics in original).

In light of the current pandemic, dystopias become ‘even more relevant for many readers as instruments of coping with this horrifying experience’ (Kleofastova et al., 2020, p. 105). Considering how the Covid-19 crisis affects social and economic aspects of our everyday life, it seems only logical that themes discussed in YA dystopian novels are given special focus at school; they show, sometimes in a very dramatic way, what can happen if people do not take immediate action and change their behaviour. The fact that these texts are fictional does not take away the power of their messages. The Fridays for Future (https://fridaysforfuture.org/) movement, for example, illustrates that more and more younger people start to reflect on universal problems. In education contexts, dystopias serve the principal function to support ‘younger generations towards seeking solutions for contemporary planet-scale problems and making the world more co-habitable for diverse cultural traditions’ (Kleofastova et al., 2020, p. 105). Dystopian fictional narratives have the capacity to frighten and warn readers with pressing global concerns (Bullen & Parsons, 2007, p. 128), but at the same time provide a ‘lesson-learning exercise: what kind of society do we want to emerge from this, and what individual and collective action must be taken in order to achieve that?’ (Zielinski, 2020). With her questions, Zielinski addresses the benefits of YA dystopian fiction: reading these texts opens up horizons to learn from those fictional stories; further, it prepares students to develop ideas to take actions. Comparisons and adaptations from current events and YA dystopian texts can also offer valuable learning opportunities. In this way, ‘the act of reading becomes the impetus to action’ (Bullen & Parsons, 2007, p. 138).

Hence, YA dystopian texts are of great importance in the field of language education. When reading YA dystopian texts, students are asked to enter futuristic worlds and respond to those representations. Today, more than ever, topics such as pandemics, global warming, digital surveillance, and social injustice are omnipresent. ‘What the imagined space and time of science fiction thus offer the reader is not a vision of a possible future, but an interrogation of the present’ (Bullen & Parsons, 2007, p. 129). YA dystopias help learners witness worst-case scenarios in a world beyond their own without actually having to go through them. This allows students to be able to discuss hypothetical solutions to issues while maintaining a safe distance.

However, there are also critical responses to dystopian novels. In her article ‘A Golden Age for Dystopian Fiction’, Lepore points out that dystopias depict the world as a negative, devastating space, ‘the fiction of helplessness und hopelessness’ (2017). She further writes that dystopias create pessimism about technology, economy, politics, and the planet. She describes dystopian texts as the ‘fiction of an untrusting, lonely, sullen twenty-first century’ (2017). In comparison to Lepore, Wolk is convinced that YA dystopian novels help students question the world we live in and envision a better world. They ‘offer unique opportunities to teach these habits of mind’ (2009, p. 668). By reading and interpreting YA dystopian texts in the classroom, negative attitudes towards using this genre can be reversed; instead of nursing grievances and indulging resentments, YA dystopian fiction can achieve the opposite. Learners are enabled to pay attention to those grievances and resentments in order to call for actions that the world will not be like the one pictured in YA dystopian texts.

Consequently, it is not surprising that dystopian texts are recommended in the German school context. A closer look at English language teachers’ opinions towards reading YA dystopian fiction in class will uncover perceptions of the benefits and challenges of dealing with this literary genre.

Prior Empirical Findings

To date, there is little empirical research that focuses on the perspectives of teachers and learners on literature in the foreign language classroom. In the case of ELT, Literature and Language Learning in the EFL Classroom (Teranishi et al., 2015) is one of the rare volumes featuring an extensive collection of empirical research on teaching practices and the effects of literary education. Consequently, in his review of existing research, Paran’s (2008) call for a stronger focus on empirical research in the field of literature in language education is still highly relevant: ‘Since most of the writing in this area has been theoretical, the challenge for research is to validate these theoretical positions, and to support the claims that literature can contribute to language learning […]’ (p. 470). The study at hand invited German secondary school language teachers’ perspectives on YA dystopian fiction to contribute to such validation. Thus, it complements existing studies in secondary education settings by focusing on a particular genre.

Bloemert, Jansen and van de Grift (2016) explored the extent to which Dutch secondary ELT teachers adopt different approaches to teaching literature. For this purpose, they conceptualized the ‘comprehensive approach’ based on a synthesis of teaching approaches published by researchers and practitioners in teaching literature. The resulting approach includes a combination of what the authors call ‘text approach’, ‘context approach’, ‘reader approach’, and ‘language approach’. Each of these individual approaches reflects specific potentials of literature in the English classroom. For example, the literature approach promotes an understanding of literature as ‘a body of texts reflecting the culturally, historically, and socially rich diversities of our world’ (p. 174). In contrast, the language approach highlights literature as a resource for language input. Bloemert et al.’s (2016) findings indicate that each of the four different teaching approaches was regularly used in the English classroom by their 106 participants. Additionally, the choice of these approaches did not correlate significantly with the teachers’ gender, years of teaching experience, or level of education. Instead, curricular factors such as the number of literature lessons per year or the learning objectives set out in the national curriculum impacted the way literature was taught.

Interviewing secondary school teachers from three different schools, Duncan and Paran (2018) investigated the ways their participants negotiated the challenges of reading literature. Their study shows that the conceptual and linguistic difficulty of literary texts, a lack of time in class, and students’ past experiences of reading were considered challenging by the participating language teachers. What is remarkable about Duncan and Paran’s approach is that they acknowledge the teachers’ perceptions by shifting the focus towards their participants’ coping strategies to tackle the challenges mentioned above. In doing so, the authors point out that the participating teachers negotiate these challenges through text choice, the organization of reading, and reading aloud. This way, the results of their study ‘present the complex bundles of factors that influence teachers’ choices of texts and activities, exposing the in- and out-of-class deliberations and decisions which are part of teachers’ daily struggles and yet all too often not shared’ (Duncan & Paran, 2018, p. 256). At the same time, their findings underline the importance of autonomy that allowed the participants to turn teaching literature into a rather personal subject matter.

Teachers’ Perspectives on Teaching YA Dystopian Fiction in the ELT Classroom

The following study was conducted in the context of the German educational system. The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) serves as a basis for the educational standards that are legally binding on a national level. YA dystopian fiction is explicitly mentioned in the curriculum of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), one of the sixteen German federal states (MSB NRW, 2019). Depending on their academic achievement at primary level, students attend one out of four types of secondary school (mainly Hauptschule, Realschule, Gymnasium, or Gesamtschule). Students at the Gymnasium and Gesamtschule can graduate with the Abitur (university entrance qualification). As part of the Abitur in the subject of English, students get to choose whether they would like to attend a basic or an advanced course. While students attending a basic course read excerpts of YA dystopian fiction to get a glimpse of the genre, students in an advanced course must read a complete novel.

Research design

The introduction to YA dystopian fiction above points out the genre’s high relevance for developing critical thinking skills and its potential to initiate learning processes on a global scale today. This study explores whether these conceptual remarks reflect the practitioners’ experiences. It was guided by the following research question: From the perspective of secondary-school teachers, what are the challenges and benefits of teaching utopia and dystopia with fictional texts in the EFL classroom?

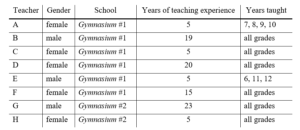

Eight in-service secondary-school English teachers (see Table 1) working at two Gymnasien in NRW, participated in semi-structured interviews. Concerning teaching experience, the group of participants is rather diverse since both novice and expert teachers were included. All teachers volunteered to participate in the present interview study in response to a formal invitation sent to several secondary schools in NRW. In this respect, the minimal group of participants is highly selective.

Table 1. Overview of participants

Table 1. Overview of participants

Semi-structured interviews were considered most suitable for this study. On the one hand, this format ensured that all interviews covered the same key aspects with the help of the interview guideline (see below). The guideline was composed based on an extensive review of conceptual research on teaching literature and dystopian fiction. On the other, this method provided the teachers with enough room to focus on those aspects that were personally meaningful to them. Consequently, the choice of a flexible interview format made it possible to bring aspects related to the research question – the teachers’ opinions on and attitudes towards teaching YA dystopian fiction – into focus without dismissing the participants’ individual preferences and additional remarks (Lamnek, 2003, p. 312). Even though all participants were qualified secondary-school teachers of English, the interviews were conducted in German to avoid misunderstandings. Prior to the interview, all participants were asked to bring at least one example of a YA text they have used to teach dystopian/utopian fiction in the past. The following list represents the interview guideline translated into English:

- Material brought to the interview: Can you tell me something about the material you brought?

- For what reasons do you use the material?

- How do you use it?

- Which material do you use besides the material you brought and the novel itself?

- Is the subject utopia and dystopia connected to the life of the students?

- If yes, how?

- If not, why not?

- Do you connect the topic to the life experiences of students?

If yes, how do you do that? - What are your experiences teaching utopia and dystopia?

- How do you like the topic?

- What are your experiences exchanging ideas with your colleagues?

Are they purely instructional-based? Or also content-based? - Which potentials and challenges does this topic pose in your opinion?

- What pros and cons do you see in teaching narrative literature?

- In your opinion, can teaching utopias and dystopias motivate students to read more?

- Would you like to add anything?

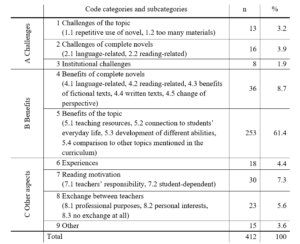

In order to investigate the research question, interview data were transcribed and analyzed with the help of structuring qualitative content analysis (Mempel & Mehlhorn, 2015). A total of 412 teacher interview statements was coded with the help of the coding frame explicitly developed for this study in a deductive-inductive process: first, main categories (e.g., reading motivation) were deduced from the literature review on teaching YA dystopian fiction in ELT; second, these tentative categories were refined and restructured based on the teachers’ statements. This process was reiterated until it did not yield any new (sub-)categories or contradictions between the existing codes. For the most part, the codes could be assigned to one of the (sub-)categories mentioned in Table 2, as the majority of teachers took a firm stance. In case a statement was considered ambiguous, it was split up. Each part was then assigned to an appropriate category. Hence, statements were not counted in more than one (sub-)category. Since all interviews were conducted in German, the resulting data was also analysed in German. However, selected excerpts of the transcripts were translated into English to make the participants’ statements accessible to the international audience of this journal. Table 2 provides a descriptive overview of the distribution of codings across the main categories and their respective subcategories.

Table 2. Distribution of codings according to each category

Discussion of results

In the following, the results of the structured qualitative content analysis will be presented and interpreted. For this purpose, we discuss code categories that deal with the same aspects of ELT from different perspectives together whenever possible (e.g., the reading-related challenges and benefits of dealing with complete novels). This approach allows us to represent the complexity and sometimes even ambiguity of certain categories. Consequently, this discussion focuses on (1) challenges related to the choice of dystopian texts and teaching resources, (2) challenges related to the accessibility of chosen dystopian texts, (3) the versatility of literature in skills-based ELT, and (4) the relevance of educational policy in ELT.

Even though this study initially sought to investigate teachers’ views on teaching both dystopias and utopias, a strong focus on YA dystopian fiction emerged during data collection. As teacher D’s statement implies, dystopian fiction appears to be much more prominent than utopian fiction in NRW’s ELT classrooms: ‘So we speak more about dystopias rather than utopias because there aren’t really any utopias available’. Crucially, there was not a single participant who reported on having taught utopian fiction in class.

Facing a hard choice: Subject matters of dystopian fiction and teaching resources

When asked about their text choice, teachers mentioned the following texts as examples of dystopias they have used in their ELT classrooms: Brave New World (teachers B, C, D, F, G, I, H), Fahrenheit 451 (teachers A, B, C, E), The Handmaid’s Tale (teachers D, F, H), Nineteen Eighty-Four (teachers E, H), Never Let Me Go (teachers D, H), The Hunger Games (teachers D, F), A Clockwork Orange (teacher G), Lord of the Flies (teacher B), The Carbon Diaries (teacher H) or The Circle (teacher A). Teacher D justified this preference for fictional texts with the characteristics of the genre (‘If I imagine teaching dystopias [exclusively] with nonfictional texts, I can only imagine very dry, boring lessons.’). In her opinion, nonfictional texts discussing aspects that have been featured in dystopias (e.g., genetic engineering) would be too theoretical and thus inappropriate for conveying the dangers of future scenarios dystopian fiction so vividly conveys.

As illustrated in Table 2, certain aspects mentioned during the interviews were evaluated ambiguously by the participating teachers. The most prominent aspects include the choice of interesting, appealing YA dystopian texts and the use of teaching resources. While all teachers appreciated the wide range of available choices, some felt overwhelmed striving to make the best decision for their highly individual classes (‘One has to try to combine all of this’, teacher E).

Regarding the choice of dystopian literature for the secondary ELT classroom, it is worth mentioning that the majority of teachers repeatedly taught the same novel in different classes despite the possibility of choosing different texts. Teacher F, for example, highlights that she keeps teaching the same novel over and over again: ‘[…] it is rather a disadvantage for us teachers. Teaching the same novel to the fifth or sixth class, one gets tired of the novel, which is a shame, because they are really good but one would need more variety’. What prevents the participants from testing new novels in these cases is their students’ continuing interest in novels they have repeatedly taught in the past (‘Sure, teaching a different novel would be a welcome change but this is not about me’, teacher B). At the same time, some teachers rely on tried and tested dystopian novels, such as Brave New World, since they consider them to be equally relevant today as they were at the time of their publication (‘A colleague said that the use of Brave New World has become more prevalent over the past few years compared to other novels. The reason given was that the novel is becoming more relevant’, teacher G). Moreover, it is noteworthy that the participants seem to hold on to those novels that resonated positively with their students.

Similar to the choice of dystopian texts, designing new or selecting from published teaching materials were described as time-consuming processes. With regard to this, the participants felt particularly challenged by the wide range of available teaching resources (‘It is hard to pick suitable material from the number of materials offered. One can really lose oneself in looking for material’, teacher H). Regardless of their choice, the participating teachers are willing to adapt published teaching resources to the needs of their students. Three teachers stated that they regularly refer to published teaching manuals when planning their lessons. Additionally, six teachers elaborated on the different media they use to complement teaching manuals that usually comprise a collection of worksheets. These media range from films (V for Vendetta) and TV series (Black Mirror) or political speeches to songs (‘In The Year 2525’ [Evans & Zager, 1969]) and newspaper articles. These multimodal teaching approaches were employed as a basis for implementing creative tasks in the ELT classroom, such as role-plays or creating a video about one of the texts read in class (teacher B), writing one’s vision of the future (teacher C), and freeze frames (teacher D).

To read or not to read: Making YA dystopian fiction accessible to students

Five out of the eight participants reported that their students experienced language-related difficulties when reading YA dystopian texts, particularly when reading complete novels. On the content-level, teacher C, for example, emphasizes the need to introduce subject-specific vocabulary prior to giving reading assignments: ‘Everything that has to do with genetic engineering has to be introduced prior to reading’. Linguistically, some teachers observe that their students fail in constructing the meaning of longer texts due to a lack of vocabulary and compensating reading strategies.

However, half of the interviewees also commented on the potential of dystopian fiction for improving their students’ language proficiency. For example, teacher H hints at the increased linguistic complexity her students are confronted with when reading dystopian novels: ‘Firstly, of course, written texts are essential for learning the language or perhaps exhausting the possibilities a language offers. One can express much more, get a different perspective on speech, and more complex speech patterns’. Engaging her students in intensive reading allows teacher H to focus on the more subtle aspects of language, such as style or register. Even though language accuracy is no longer of primary concern in ELT classrooms, the input these texts provide covers a wide range of language characteristics students might reuse for their own communicative purposes (Kramsch, 1996, p. 183).

What all of the participating teachers agree on is that the majority of their students do not enjoy the process of reading itself. As teacher E puts it: ‘Well, one of the advantages from the point of view of the pupils [in a basic English course] is that they definitely don’t have to read a whole book: they have no enthusiasm for that’. The participants in this study relate this lack of enthusiasm to two different aspects: First, they find it challenging to find texts that are appealing to all students in their classes; as a result, some students might stop participating in class because they simply are not interested in the novel. Second, teachers assume that their students are no longer used to reading long texts (‘for others a novel is simply too long. They do not have the stamina to read such a long text’, teacher G).

At the same time, four interviewees depicted the benefits connected to reading dystopian fiction. On the one hand, they are convinced that reading a text over several weeks results in a deeper level of engagement and understanding than watching an adaptation. On the other hand, the challenge of having to read a whole dystopian text allows students to improve their reading comprehension and ‘to have read, to find one’s own reading rhythm, to learn how to simply concentrate on a book and put aside their cell phone’ (teacher E).

Finally, yet importantly, all teachers argued that they preferred choosing dystopian texts featuring central themes that concern their students. As part of this argument, teachers named different aspects of their students’ everyday life that also occur in dystopian texts read in class. These include, among many others, totalitarian regimes and the denial of human rights (teachers D, E, H), the pitfalls of social media (teachers A, C), and scientific and environmental issues (teachers F, H): ‘I mean, if you look at The Circle and then the headquarters of Google, it is not that much off’ (teacher H). Statements like this help clarify that – according to the teachers – the visions of the future promoted in dystopian fiction are not as visionary as they seem to be. The teachers assume students’ interest in these topics based on their class participation. Teacher A, for example, observed that ‘the desire to speak is already great so that they feel they are being spoken to and, as it is relevant to their world, they wish to communicate’. Students feel the urge to express their personal opinion on current issues, which initiated fruitful in-class debates.

Interestingly, most participants did not consider the date of publication of a YA dystopian text when judging its relevance for their students. Based on their teaching experience, canonized works such as Nineteen Eighty-Four are just as appealing to their students as more recent publications. Generally speaking, all interviewed teachers pointed out the potentials connected to the wide variety of topics addressed in YA dystopian fiction. The various social, scientific, cultural, and political aspects usually covered by these texts cater to the heterogeneous learning groups’ interests.

The versatility of teaching YA dystopian literature in the ELT classroom

All participants pointed out that teaching literature in general – YA dystopian fiction in particular – covers a great variety of skills. One of the most prominent aspects all teachers addressed was facilitating intercultural communicative competence through literature. Some of the teachers assumed that the discussion of a literary text over a relatively long period of time helps students empathize with main characters they can relate to, thus allowing them to adopt new perspectives (‘[…] how they [the characters] fail or succeed and that they [the students] can identify with the characters more when they read about them for several weeks’, teacher F). Consequently, dystopian fiction contributes to the overarching goal of intercultural communicative competence in the German ELT classroom (Freitag-Hild, 2018).

Apart from that, all teachers emphasized that dystopian fiction bears the potential for promoting their students’ critical thinking skills as a prerequisite to participating in society. In particular, texts dealing with societal issues such as inequality could help students to reflect upon their own behaviour and the characteristics of contemporary societies (‘the students were thankful that someone showed it to them in this manner; in part, a mirror was held up to their behaviour’, teacher A). Moreover, teacher H claims that engaging with fictional dystopian scenarios makes her students aware of their role in impacting future developments concerning humanity and the environment (Grimm, Meyer & Volkmann, 2015, pp. 192-193). In class, this awareness sometimes resulted in discourses on political activism that were partly related to the rising popularity of the Fridays for Future movement at that time (‘what can we do today so that in 10 years, the animal population won’t become extinct or the planet won’t be overwhelmed with flooding and heat-waves,’ teacher F).

Finally, it is necessary to point out that the teachers had mixed opinions on the effectiveness of teaching dystopian fiction for enhancing their students’ reading motivation. Teacher E did not notice any positive effects and considers reading motivation to be a static attribute (‘I believe it is a fundamental attitude’). Teacher B, however, observed students ‘who then devoured one book after another, who wanted to give a presentation on books that they had read in addition to the text in class’. While the present study’s results do not allow drawing any general conclusions, teacher B’s account – once again – highlights the potentials of literature in ELT.

The relevance of educational policy to teaching literature in the ELT classroom

As becomes evident in the data, the teachers participating in this study are all very enthusiastic about teaching literature and thus dedicated to providing their students with the best learning opportunities possible. They did not shy away from expressing their concerns about educational policies that interfere with their teaching ideals.

Regarding the amount of prescribed, mandatory topics in the curriculum of NRW, several teachers felt they were pressed for time during their ELT lessons. For example, some teachers perceived that their students were denied the opportunity to engage with demanding dystopian texts on a deeper level: ‘The students dive deep into this subject matter, and then frequently they ask, that was it? Do we have to continue with a different topic?’ (teacher H). Additionally, the politically established accountability of schools for their students’ academic achievement results in teaching to the test. As teacher A criticizes, the increased importance of the Abitur prevents students from reflecting upon literature since it is reduced to a means of achieving good grades: ‘I always think it is disappointing, but this is a bit of criticism against educational policy in general. After writing an exam on a particular subject, students often stop engaging in class. They think okay, we took the exam, so let’s move on’.

The last aspect was only addressed by one teacher; however, we think that it is worth mentioning since it sheds a light on the way EFL students’ academic achievement is assessed in NRW. Teacher H points out that the primary form of assessment during the last three years of secondary school are written exams, with only one oral exam: ‘We still have exam formats that concentrate on writing ability. Suppose I only experience heard speech, spoken speech in this sense. In that case, I am missing a great aspect of written text and the correct use of written language. All in all, written text is still our core business’. In teacher H’s opinion, reading and working with complete literary texts, such as dystopian fiction, is indispensable for students to hone their writing skills.

Discussion and Conclusion

The experiences in teaching dystopian fiction in the ELT classroom that the participating teachers reflected upon show that the topic is ‘very, very exciting’ (teacher A) and one of the ‘most fundamental’ (teacher H) listed in the curriculum. From the perspective of the teachers, these positive evaluations testify to the genre’s significance for ELT that we touched upon in the first section of this paper. Generally speaking, all teachers agreed that their students immensely enjoy dystopian fiction in comparison to other topics prescribed in the curriculum (MSB NRW, 2019), such as ‘American myths and realities’ or ‘The impact of Shakespearean drama on young audiences today’ (‘The topic is always very, very popular […] the pupils get really involved in this subject matter’, teacher C). However, our findings indicate that the students’ involvement depends heavily on the choice of appealing dystopian texts and how they are implemented in the ELT classroom. These observations might motivate practicing and future language teachers to vary their dystopian fiction selection from time to time, although this might result in additional work.

As became evident, the participants tend to keep teaching dystopian texts that were once explicitly prescribed in NRW’s curricula. This proves that educational policies and schools contribute substantially to the canonization of literary works (Kirchhoff, 2019). The dystopias mentioned by participants in our study partly reflect the results from the surveys conducted by Nünning (1997) and Kirchhoff (2016) (e.g., Brave New World, Lord of the Flies, Fahrenheit 451, or Nineteen Eighty-Four).

Looking back at prior empirical findings, the aspects discussed by the participants can be compared to the results of Bloemert et al. (2016). To some extent, all teachers adopted a reader approach and language approach. Dystopian fiction was employed to improve students’ critical thinking skills and adopt new perspectives on global issues. Furthermore, teachers considered complete dystopian novels a valuable source for language input. In addition to that, our teachers’ testimonies confirmed the negotiation of challenges through text choice (by considering a text’s accessibility, its appeal, and different methodological ways gaining insight into the text) found by Duncan and Paran (2018).

Dystopian narratives offer various learning opportunities for young adults to deal with the challenges that could lead to dark futuristic scenarios (e.g., Bland, 2018; Kleofastova, Vysotska & Muntian, 2020). Results from interviews with teachers illustrate that practitioners see dystopian texts as sources for students to identify future challenges and enable students to change perspectives when working with these fictional texts. We are aware of the fact that findings from this exploratory study cannot be generalized. Likewise, the results open new avenues for future research. Based on these findings, future empirical and theoretical studies could set out, for example, to investigate questions such as these: (a) What are students’ perspectives on reading dystopian texts in the secondary ELT classroom with regard to learning potential and learner motivation? (b) What are the reasons for students not wanting to read complete dystopian texts? (c) How can dystopian texts be used in cross-curricular learning? (d) To what extent are white male authors from Western societies overrepresented in YA dystopias?

Bibliography

Atwood, Margaret (1995). The Handmaid’s Tale. Anchor.

Bradbury, Ray (1953). Fahrenheit 451. Ballantine Books.

Burgess, Anthony (1962). A Clockwork Orange. W. W. Norton & Company.

Collins, Suzanne (2008). The Hunger Games. Scholastic.

Eggers, Dave (2013). The Circle. Penguin.

Elsberg, Marc (2017). Blackout, translated Marshall Yarbrough. Sourcebook.

Evans, Rick & Zager, Denny (1969). [Song] In The Year 2525. RCA Victor. https://youtu.be/jP36qymmCtg

Golding, William (1954). Lord of the Flies. Penguin Books.

Huxley, Aldous (1932). Brave New World. Chatto&Windus.

Ishiguro, Kazuo (2005). Never Let Me Go. Vintage International.

Black Mirror (2011). [TV series] Created by Charlie Brooker. Endemol Shine UK.

Lloyd, Saci (2009). The Carbon Diaries: 2015. Holiday House.

Orwell, G. (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four. Secker & Warburg.

V for Vendetta (2005). [Film] Dir. James McTeigue. Warner Bros. Pictures.

References

Alter, A. (2019). ‘The Hunger Games’ prequel is in the works. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/17/books/hunger-games-prequel.html

Baccolini, R. & Moylan, T. (2003). Introduction: Dystopia and histories. In R. Baccolini & T. Moylan (Eds.), Dark horizons, science fiction and the dystopian imagination (pp. 1-12). Routledge.

Bland, J. (2018). Popular culture head on: Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8–18 year olds (pp. 175-192). Bloomsbury Academic.

Bloemert, J., Jansen, E. & van de Grift, W. (2016). Exploring EFL literature approaches in Dutch secondary education. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29(2), 169-88.

Bucher, K. & Hinton, K. (2010). Young adult literature. Exploration, evaluation, and appreciation. Pearson Education.

Bullen, E. & Parsons, E. (2007). Dystopian visions of global capitalism: Philip Reeve’s Mortal Engines and M. T Anderson’s Feed. Children’s Literature in Education 38, 127-139.

Caspari, D. (2007). À la recherche d’un genre encore mal connu: Zur Erforschung von Kinder- und Jugendliteratur für den Französischunterricht. Französisch Heute, 38(1), 8-19.

Delanoy, W. (2018). Literature in language education: Challenges for theory building. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8–18 year olds. (pp. 141-158). Bloomsbury Academic.

Duncan, S. & Paran, A. (2018). Negotiating the challenges of reading literature: Teachers reporting on their practice. In J. Bland (Ed.), In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8–18 year olds (pp. 243-260). Bloomsbury Academic.

Freitag-Hild, B. (2018). Teaching culture – Intercultural competence, transcultural learning, global education. In C. Surkamp & B. Viebrock (Eds.), Teaching English as a Foreign Language (pp. 159-175). Metzler.

Green, J. (2008). Scary new world. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/09/books/review/Green-t.html

Grimm, N., Meyer, M. & Volkmann, L. (2015). Teaching English. Narr Francke Attempto.

Kirchhoff, P. (2019). Kanondiskussion und Textauswahl. In K. Stierstorfer & C. Lütge (Eds.), Grundthemen der Literaturwissenschaft (pp. 219-230). Walter de Gruyter.

Kirchhoff, P. (2016). Is there a hidden canon of English literature in German secondary schools? In F. Klippel (Ed.), Teaching languages. Sprachen lehren. (pp. 229-248). Waxmann.

Kloefastova, T., Vysotska N. & Muntian, O. (2020). Teaching anti-utopian/dystopian fiction in RFL/EFL classroom as intercultural awareness raising tool. Arab World English Journal: Special Issue on English in Ukrainian Context, November, 102-112.

Kramsch, C. (1996). Stylistic choice and cultural awareness. In L. Bredella (Ed.), Challenges of literary texts in the foreign language classroom (pp. 162-184). Narr Francke Attempto.

Lamnek, S. (2003). Qualitatives Interview. In: E. König& P. Zedler (Eds.), Qualitative Forschung, Grundlagen und Methoden. Beltz.

Lepore, Jill. (2017) A golden age for dystopian fiction. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/05/a-golden-age-for-dystopian-fiction

Lipari, A. (2019). Benefits and challenges of teaching utopia and dystopia in the secondary EFL classroom from the teachers’ perspective: An interview study [unpublished MEd thesis].

Matz, F. (2015). Alternative worlds – Alternative texts: Teaching (young adult) dystopian novels. In W. Delanoy, M. Eisenmann & F. Matz (Eds.), Learning with literature in the EFL classroom (pp. 263-282). Peter Lang.

Matz, F. (2019). The challenge of teaching dystopian narratives in the global age: Learning about the terrors of the 21st century in the EFL classroom. In E. Thaler (Ed.), Lit 21 – New literary genres in the language classroom (pp. 61-70). Narr Francke Attempo.

Mempel, C. & Mehlhorn, G. (2015). Datenaufarbeitung: Transkription und Annotation. In J. Settinieri, S. Demirkaya, A. Feldmeier & N. Gültekin-Karakoç (Eds.), Empirische Forschungsmethoden für Deutsch als Fremd- und Zweitsprache: eine Einführung (pp. 147-165). Schöningh.

MSB NRW [Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen] (2019). Zentralabitur 2021 – Englisch – geänderte Fassung. Düsseldorf.

Nünning, A. (1997). Perspektivenübernahme und Perspektivenkoordination. Prozeßorientierte Schulung des Textverstehens und der Textproduktion bei der Behandlung von John Fowles’ The Collector. In G. Jarfe (Ed.), Literaturdidaktik – konkret. Theorie und Praxis des fremdsprachlichen Literaturunterrichts (pp. 137-161). Winter.

Paran, A. (2008). The role of literature in instructed foreign language learning and teaching: An evidence-based survey. Language Teaching, 41(4), 465-496.

Teranishi, M., Saito, Y. & Wales, K. (2015). Literature and language learning in the EFL classroom. Palgrave Macmillan.

Wolk, S. (2009). Reading for a better world: Teaching for social responsibility with young adult literature. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 52(8), 664-673.

Zielinski, C. (2020). I’ve been reading more dystopian fiction than ever during the Corona crisis. Here’s why. The Guardian. International Edition. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/apr/08/ive-been-reading-more-dystopian-fiction-than-ever-during-the-corona-crisis-heres-why