| The Multilingual Picturebook in English Language Teaching: Linguistic and Cultural Identity

Nayr Ibrahim |

Download PDF |

Abstract

The many benefits of using picturebooks in the primary classroom include language development as well as an introduction to real-world issues through storytelling and fictitious characters that children can relate to. However, the representation of diversity in children’s literature, both cultural and especially linguistic, has been inadequate. Even though there is a drive to increase cultural diversity in children’s literature, from a linguistic perspective there is still a dearth of multilingual literature in English as foreign language classrooms, for example, selected picturebooks tend to be mostly monolingual. Although they offer a window to difference in faraway places and a mirror of otherness closer to home through the characters and illustrations, they don’t always acknowledge the linguistic aspect of the cultures they are highlighting. Yet, language reinforces the differences and similarities in cross-cultural spaces. This paper investigates the potential role of multilingual picturebooks in the primary EFL classroom. First, it explores the multilingual-multicultural nexus; next, it investigates the representation of cultural and linguistic diversity in picturebooks; finally, it uses the bilingual picturebook, Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina (2011), by Monica Brown and Sarah Palacios (illustrator) to identify the benefits of a multilingual approach to developing intercultural citizenship.

Keywords: multilingualism; linguistic diversity; intercultural; identity; dual language; bilingual picturebooks

Nayr Ibrahim is Associate Professor of English Subject Pedagogy at Nord University. Her publications include Teaching Children How to Learn (with Gail Ellis, 2015). Nayr is a member of the Nord Research Group for Children’s Literature in ELT (CLELT) and associate editor for the CLELEjournal. Her research interests include early language learning, learning to learn, bi/multilingualism, language and identity, children’s literature, children’s rights.

Introduction

This paper explores the potential for extending interculturality in the English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom by including a specific focus on multilingualism through the use of multilingual picturebooks. The manifold benefits of using picturebooks with young children in early language learning have been expounded in a rich and varied repository of interdisciplinary research into the picturebook as an artefact (Mourão, 2015), and as a pedagogical tool (Ellis & Brewster, 2014). The picturebook in the EFL classroom has attracted attention from both practitioners and researchers in the last 30 years, becoming a popular language-rich resource with multiple educational benefits, for example exposing young learners to authentic language and enhancing the enjoyment of foreign language learning; integrating values education (Hall, 2010); highlighting diversity issues (Ellis, 2010); and teaching, not only the culture(s) of English, but also exposing children to multiple cross-cultural realities (Bland, 2020). According to Dolan (2004: 3), picturebooks can ‘bridge the gap between geographically distant places and the lives of children in the classroom’, through the interplay of words and pictures, which allow the child to learn to read the word and the world (Freire & Macedo, 1987). In spite of the growing interest in multicultural and multilingual literature in ELT generally, particularly ESL, EAL and heritage language contexts, the bridge to other cultures and different worlds in the EFL classroom has been grounded in a monolingual mindset.

If the picturebook provides a window on the world, the view from this window has primarily centred on the exclusive perspective of the English language. This belief in an English-only approach has its roots in the Direct Method, popularized by Berlitz in the early 20th century, where teaching, learning and thinking should occur directly in the target language (Kerr, 2014). The language learner is required to exclude their other languages from the learning experience for fear of interference or contamination. Even though this approach may have been adhered to in some EFL contexts, for example, private or after-school education, in others, such as mainstream schools, teachers often continued to use the majority language or ‘shared classroom language’ (Ellis & Ibrahim, 2015). Copland & Neokleous (2011) tell us of ‘teachers underreporting or ‘differently’ reporting their L1 practices’ (p. 271), which indicates a sense of guilt at transgressing the English-only policy. These approaches and perspectives ultimately ignore children’s other languages and dismiss the use of more inclusive plurilingual approaches. Consequently, it may result in EFL teachers not selecting multilingual children’s literature, ignoring the ‘foreign’ words in interlingual picturebooks or, at best, according a cursory glance at their presence in the text. This has implications for the child’s multilingual and multicultural development. On the one hand, it is important for both monolingual and plurilingual children and their teachers to understand that the world is not linguistically sanitized or monolingually compartmentalized. It is invariably multilingual and this interplay between the cultural and the linguistic elements of both local and global interaction deconstructs the monolingual myth and expands the complexity and multidimensionality of intercultural communication. On the other hand, the plurilingual children in our classrooms bring invaluable resources and knowledge of a linguistic and intercultural nature to their English language learning.

I start by exploring the multilingual-multicultural nexus, so as to reinforce the link between languages and the development of multiple perspectives and deconstruct the narrow one-language-one-culture bias. Going beyond the visual and content mirror of children’s literature, a focus on language(s) acknowledges the multilingual world that children inhabit, contribute to and influence. The potential of this multilingual-multicultural crossroads enriches intercultural perspectives, while encouraging a pedagogy of noticing, and active engagement with other languages. In the second part, I give a brief overview of the representation of cultural and linguistic diversity, or a lack thereof, in picturebooks, and introduce the concept of the bilingual picturebook.

In the third part of the paper I explore the potential of bilingual picturebooks for fostering a deeper understanding of intercultural and multilingual learning in the ELT classroom through the picturebook, Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina (2011), by Monica Brown, Sarah Palacios (illustrator) and Adriana Dominguez (translator). This picturebook integrates Spanish and English and serves as a sliding door (Sims Bishop, 1990) into the colourful world of a bilingual / bicultural household. Through a complex interplay of the dual language text, instances of translanguaging and the illustrations, this picturebook depicts the meshing and fluid lives of children negotiating a plurilingual identity.

The Globalized World and the Dangers of ‘A Single Story’ (Ngozi Adichie, 2009)

Societies in the 21st century have experienced an unprecedented influx of peoples from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Whether they are refugees fleeing war-torn zones, migrants looking for better livelihoods or people following job opportunities and career advancement, they have contributed to creating and enhancing super-diverse, multi-layered and multilingual communities: ‘In this age of communication transformation and penetrating globalization, languages and cultures come into contact constantly – driven by conflicts, migration, media, transnational capitalism and many other factors’ (Dooly & Vallejo, 2018, p. 2). This globalized world creates highly diverse spaces at our doorstep that we are compelled to engage with.

Children are an integral part of these processes, both at a linguistic and cultural level. They develop multiple languages in the family context, pick up languages in the community and / or learn languages at school. These complex linguistic biographies account for an uneven, eclectic constellation of linguistic resources and funds of knowledge. This imperfect (according to the monolingual paradigm) multilingual population is entering schools, with clearly defined language spaces and unchallenged separate-language ideologies. This ideology sometimes results in negative reactions to children’s languages in the school space, for example a nine-year-old student was punished for speaking Turkish during the break in a German school (Daily Sabah, 2020) and, according to a Finnish newspaper, Sweden has been referred to the European Court of Human Rights for language discrimination, that is, prohibiting Finnish-speaking children from speaking Finnish during the school day (Oliver Smith, 2020). This reality is forcing both practitioners and researchers to question the linguistic ideological status quo and reconceptualize language education from a contextual (Chevalier, 2015), equitable (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2000) and identity (Ibrahim, 2014) perspective.

The primary English language classroom is not immune to the phenomenon of super-diversity. As an international language that is taught all over the world, English is increasingly adopted as a basic skill (Graddol, 2006) in policy decisions (Enever, 2018). It has the uncontested status of a lingua franca (Jenkins, 2007), and different Englishes have developed in different parts of the globe (Mesthrie & Bhatt, 2008). Hence the English language is quite diverse itself, having encountered, influenced and integrated different cultures, and affected and incorporated different languages (British Council, 2013). Voices from the foreign language classroom are dismantling linguistic barriers by reserving a strategic place for children’s languages in the learning process (Copland & Ni, 2018;). Besides, children’s language and cultural rights are now enshrined in international law (UNCRC, 1989) as

it is the fundamental rights of children to access their language repertoire, not just as a one-off scaffolding technique or a tolerated approach: but as an acknowledgement of their plurilingual identity, as a contribution to their socio-emotional well-being and as recognition of children’s agency in choosing how they prefer to learn a new language. (Ibrahim, 2019, p. 27)

A vision of the world in which cultural diversity is accessed through one language only tells one story, a single story, one single monolingual story. Hence, professionals in this learning configuration should be encouraged to acknowledge and dissect the hegemonic status of English and dispel the monolingual bias. They can do this by interweaving the languages and cultures of the children and engaging with the translingual practices that characterize multilingual communication. One such practice is translanguaging, which Canagarajah (2011) describes as the ‘ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoires as an integrated system’ (p. 401). They can also integrate appropriately selected picturebooks into the learning process. These literary encounters in the space of the English language classroom constitute a reciprocal process and an unprecedented opportunity to mirror, and create a window to explore the multicultural-multilingual nexus.

Intercultural, and Multilingual, Learning: The Multilingual-Multicultural Nexus

There has been a long tradition of integrating other educational aims in foreign language teaching with young learners that goes beyond linguistic skills (reading, writing, listening and speaking), sub-skills (grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation) and instrumental perspectives (better job prospects, travel or study abroad). One such educational aim is intercultural learning, where learning to communicate across language and cultural borders is an important life skill. Driscoll and Simpson (2015) argue that ‘fostering an open mindset, developing tolerance, cultural sensitivity and an acceptance and understanding of diversity in increasingly multilingual and multicultural societies are essential features in preparing young people for a future which is not confined by local, regional or national borders’ (p. 168). Currently, the focus on intercultural citizenship education (Byram, 2008) encourages teachers ‘to link the language learning that takes place in classrooms with the community, such as by inspiring students to engage in some form of civic or social action at the local, regional, or global level’ (Porto 2019, p. 142).

More than ever, and in the current climate of anti-racism and anti-discrimination movements such as the Black Lives Matters protests, education is obliged to incorporate a social justice perspective. Education needs to bring race issues to the fore, and tackle all forms of inequalities and discrimination overtly. Husband (2019) compares the ‘colorblindness’ to a ‘color-consciousness’ approach to education when dealing with issues of colour and race. He exhorts educators to respond explicitly to ‘individual racial differences in classrooms and schools in meaningful and substantive ways’ (p. 1060). Dervin & Gross (2016, p.3) discuss ‘an approach to intercultural competence that […] points coherently, cohesively and consistently to the complexity of self and the other’. Hence, the need to acknowledge the ‘diverse diversities’ (Dervin, 2010) of the linguistic and cultural self and make these differences visible in social and educational spaces. This can be achieved by supporting teachers in resisting and transgressing separate-language ideologies and providing them with the tools to deal with these issues sensitively and confidently. Heugh (2019), exhorting a greater focus on multilingualism from the global South, uses the term ‘transknowledging’. This idea describes the action of translating knowledge from one language to another as a two-way process of mutual exchange. Creating a space for active engagement with different knowledge systems in the classroom gives children an authoritative voice, positions children as agentive meaning-makers and acknowledges their expertise in cross-cultural and cross-language knowledge exchanges.

The focus on developing citizens for a global society has crept into European and national curricula, where there is an attempt to recognise the linguistic aspect. The European Commission (2011) combines the linguistic and cultural dimensions in early language learning: ‘opening children’s minds to multilingualism and different cultures is a valuable exercise in itself that enhances individual and social development and increases their capacity to empathize with others’ (p. 7). The Companion Volume to the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2018) includes references to both a plurilingual and pluricultural, as well as a mediational competence. Furthermore, the updated Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (European Union, 2019) describe the language components in a more integrated manner: it eliminates the divisions between ‘Communicating in the mother tongue’ and ‘Communicating in a foreign language’ in the original version (European Union, 2006) and creates an integrated ‘Multilingual competence’ and a much needed ‘Literacy competence’. These new categories acknowledge that all children, including newly arrived children in different contexts, need to develop oral as well as literacy skills in multiple languages, including foreign languages.

In Norway, where I am writing, language and cultural diversity are intertwined in the new Norwegian curricula: the core curriculum (Overordnet del – verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen, 2019), the English Curriculum (Læreplan i engelsk, 2020), and the foreign languages curriculum (Læreplan i fremmedspråk, 2020), which is a separate document from the English curriculum and encompasses other foreign languages taught in Norway. This focus on diversity aims to support children in developing a strong sense of identity. The school has the responsibility of ‘helping each student to safeguard and develop their identity in an inclusive and diverse community’ and ‘all pupils shall experience that being proficient in a number of languages is a resource, both in school and society at large’ (Ministry of Education and Training, 2019, p. 4-5). However, the term ‘multilingual’ only appears in the English curriculum (Læreplan i engelsk, 2020): ‘Pupils should be given a basis for seeing their own and the identity of others in a multilingual and multicultural context’ (p. 3, all quotations from the Læreplan i engelsk and Læreplan i fremmedspråk are my translations from the Norwegian), where identifying connections between languages is encouraged: ‘Language learning involves seeing connections between English and other languages the students know, and understanding how English is structured’ (p. 2). There is also an explicit reference to ‘Language learning and multilingualism’ and ‘Intercultural competence’ in the curriculum for foreign languages (Læreplan i fremmedspråk, 2020).

Even though the linguistic element underlies curriculum aims, in practice the language(s) issue has been marginalized from intercultural learning and mediation. Very often language only constitutes a vehicle for discussions of otherness, without it being the explicit object of the discussion. Heugh (2018) insists that the challenge of contemporary diversity in education is to recognize the implications of heterogeneity because ‘heterogeneity cannot deliver a homogenized, singular set of definitions for how and why linguistic diversity occurs in many different ways, scales and dimensions across the varied contexts of the world’ (p. 347). Besides, multilingualism research is questioning the traditional view of ‘languages as whole, bounded systems, lined up as neatly as possible with political, cultural and territorial boundaries’ (Heller, 2012, p. 24). More recently, researchers are encouraging a holistic view of multilingualism (Cenoz, 2013) where languages are seen as dynamic, hybrid and multidirectional communicative resources, and where individuals negotiate meaning across their complex linguistic repertoire. As a result, there are a growing number of projects attempting to operationalise multilingual perspectives in different educational contexts: for example, the 3M (Meer kansen met Meertaligheid – More opportunities with Multilingualism), in which a holistic model for multilingual education was implemented in a bilingual province in the North of the Netherlands, Fryslân, where national, regional, foreign, and many minority languages co-exist (Duarte & Günther van der Meij, 2018); and the MEG-SKoRe (Hopp, Jakisch, Strum, Becker & Thoma, 2020) project in Germany, which studied ‘the contribution of minority languages to early FL learning’ (p. 147) and proposed a framework of Multilingual Language (Learning) Awareness in the EFL classroom.

Language diversity is inextricably linked to children’s lived experience and emerging linguistic and other identities. Robles de Melendez & Ostertag (2010) advance that ‘because language is a crucial cultural element, making children aware of its value and significance is important’ (p. 150). Various studies on emerging linguistic identities in children and teenagers highlight their ability to move between languages and world views and make appropriate choices about deploying their communicative and intercultural resources. Pennycook (2012, p.100) refers to ‘resourceful language use’ as the ability not only to move between languages but to shift between styles, discourses and register. The recent focus on using visual and creative methods in child-friendly research methodology have placed children on centre stage. It allows researchers to better understand how children manipulate the language and cultural resources in the ‘hybrid’ or ‘third space’ (Bhabha, 1994). Ibrahim (in press) discusses the choices of a Farsi-English-French trilingual child in describing an Iranian dish using her multiple multimodal resources: English and Farsi, the Arabic script, a transcription of the Arabic writing into Latin script in square brackets and a colourful drawing of the dish, supported by an oral description. This child employs her multilingual resources, a well-developed intercultural communicative competence and her multimodal skills, to ensure her interlocutors understand her explanation. This intercultural lens brings multiple perspectives to children’s lives and helps them see their own cultural identities vis-à-vis the other. The multilingual lens provides different ways of describing the world and characterizing a local and global, cultural and geographical reality. Languages encapsulate lived experiences yet one language limits the possibilities of experiencing a multitude of viewpoints simultaneously. Using Husband’s (2019) terminology, I argue we need to move from a language-blind to a language-conscious approach.

The Multilingual-Multicultural Nexus in Picturebooks

Parallel to these developments, educationalists have highlighted the potential of picturebooks for integrating intercultural learning. Short (2011) states that authentic children’s literature ‘expands children’s life spaces through inquiries that take them outside the boundaries of their lives to other places, times, and ways of living’ (p. 50).

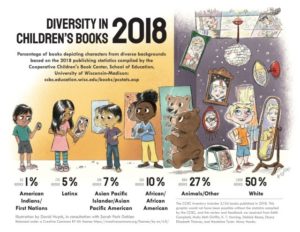

Multicultural literature has gained a special place in mainstream curricula for reasons of fairer representation of minoritized groups. Even though the number of multicultural books has increased, it has been a slow process. This is evident in the now viral infographics, Diversity in Children’s Books 2015 and Diversity in Children’s Books 2018 (Huyck & Dahlen, 2019). Not only is there still a dearth of books that fairly represent minorities, but there is also a misrepresentation of underrepresented groups, depicted by the cracks in the mirrors introduced in the 2018 version (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Representation of diversity in children’s books from US publishers in 2018

Consequently, multicultural picturebooks have a representative function. They serve as a mirror to the visible, yet ignored and veiled diversity already existent in society and in classrooms today, and promote equity and social justice. Cotton and Daly (2015) stress the importance of reading visual narratives for children’s understanding of their own identities (p. 90), otherwise ‘if children never see themselves in books, that omission subtly tells these young people that they are not important enough to appear in books, that books are not for them’ (Galda & Callinan, 2002, p. 277). Through these books minoritized migrant and refugee children see themselves represented in the literature and their diverse identities, backgrounds, languages and experiences become important sources of their education.

The literature on the educational benefits of picturebooks in the ELT classroom is increasing. Ghosn (2002) discusses the ‘potential power of good literature to transform, to change attitudes, and to help eradicate prejudice while fostering empathy, tolerance, and an awareness of global problems’ (p. 76). More recently, Heggernes (2019) explores a dialogic approach in driving intercultural dialogues forward (p. 41) and Bland (2020) focuses on literature working on the reader where ‘conflict, tension and resolution, allow the cultural, literary and language input to become more memorable’ (p. 72). Yet, even though picturebooks may be selected for their intercultural and multicultural merits, children in EFL classes are still exposed to intercultural diversity through the English language only.

Monolingualizing and Demonolingualizing, Children’s Literature

I argue that this visible and welcome increase in multicultural literature in the intercultural classroom, supported by authentic, socially-relevant picturebooks, requires a linguistic lens. However, multilingualism in picturebooks has not always been present and plurilingual children, with their translingual practices and cross-cultural experiences, are underrepresented. In order to understand the position of multilingual picturebooks we have to turn to the scholarly literature being developed in EAL, ESL and heritage or indigenous language contexts.

Nicola Daly, working in heritage language contexts, has shone a light on the ‘relative silence of languages in multilingual picturebooks’ (2019a). She has conducted research into translanguaging in dual language Māori-English picturebooks (2019b), where the existence of Māori words in the English text provide a ‘window between worlds’ (2014, p. 35), with far- reaching multilingual and multicultural implications. First, the Māori ‘readers are “hearing” their own voices in the stories’ (p. 43). Second, these picturebooks foreground indigeneity, making the Māori language and culture visible, thus legitimizing, and contributing to the revitalization of indigenous languages. Dual language books also ‘address the diverse ethnic and linguistic composition of classrooms, as they target home language literacy and literacy development in English’ (Naqvi, Thorne, Pfitscher, Nordstokk, & McKeoughat, 2013, p. 4). In her analysis of over 200 Spanish-English dual language books, Daly (2018) shows that ‘when viewed as a linguistic landscape, the languages used in a picturebook reflect the relative status of languages, attitudes towards the languages, and perhaps also the purpose of the book’ (p. 558). Daly uses the concept of the linguistic landscape within the wider meaning of the term, which refers to the presence of languages in the environment (Landry & Bourhis, 1995). In this case, not only do dual language picturebooks support linguistic diversity but ‘the presence of a minority language in a linguistic landscape can also serve as a status symbol. This status may encourage readers to use their language more frequently and in a wider range of domains, thus positively affecting the ethnolinguistic vitality of the minority language community’ (p. 558).

Despite the growing number of studies in EAL, ESL or heritage language contexts, very little research has been conducted into multilingual literature in the EFL classrooms. Kersten and Ludwig (2018) explore the use of multilingual literature, using Anzaldúa’s Friends from the Other Side/Amigos Del OtroLado (1995) to reflect ‘the continuum of linguistic skills of meaning-making at a learner’s disposal’ (p. 8). They argue for a translanguaging pedagogy (García & Li, 2014) to break down the false language divisions created by the monolingual bias, and create ‘translanguaging spaces’ in foreign language classrooms. Bergner (2016) describes a bilingual German-English approach to exploring a linguistically challenging book, Azzi in Between (Garland, 2012), yet children’s other languages are not mentioned. Rather than viewing linguistic diversity through a deficit lens, these studies are tentatively shining a light on the potential for integrating multilingualism in EFL classrooms, even if they do not necessarily exemplify an active engagement with it. Transforming languages into assets and resources gives learners a deeper understanding of the language diversity in society (Husband, 2019, p. 1061). According to Applegate and Applegate (2004), readers ‘see reading as active immersion into a text and the opportunity to live vicariously through the situations and lives of its characters’ (p. 554). A combination of bilingual picturebooks with instances of translanguaging contributes to children’s experiencing a linguistically diverse world vicariously. This is what Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina offers the reader, allowing plurilingual children, with their complex identities, to see themselves represented.

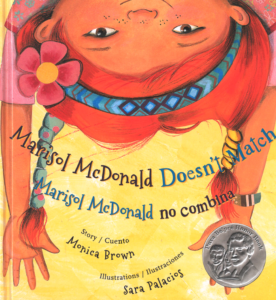

Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina

Bilingual picturebooks offer ‘the same narrative in two languages, typically English and another target language, with illustrations to link visual and textual representations’ (Naqvi et al., 2013, p. 4). Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina (see Figure 2) is a bilingual picturebook with interlingual elements, that is, it combines the parallel text in two languages, English and Spanish, which appears separately across the double-page spreads, with instances of translanguaging in the dialogue. This translanguaging element is also visible in the illustrations as Spanish and English words appear visually in some of the illustrations. For example, when the word ‘Perú’ is written on kitchen items, such as jugs and bowls, not only do the designs on these cultural artefacts attempt to capture Peruvian artistic traditions, but Peru is written with an accented ‘ú’. These subtle visual-linguistic representations introduce an element of authenticity to Marisol’s bilingual and bicultural family interactions, and an opportunity for metalinguistic discussions.

Figure 2. Cover of Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina

Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina is about a young girl with an American father and Peruvian mother living in America. Her life at home, her physical appearance and her choices are a patchwork of the multiple cultural and linguistic experiences, which are interwoven into the bilingual text and the subtle artistic elements in the illustrations. Marisol does not match in any conventional sense and her outrageous dress sense is a strong visual representation of her complex multicultural and multilingual life. Yet, contrary to what monolingual thinking would have us believe, this is not a deficit ‘lifestyle’. Marisol is not depicted as suffering from this mélange. On the contrary, she reflects the expert, creative and imaginative strategies that plurilingual children often use to synthesise the experience of living between multiple cultural and linguistic experiences. These are key intercultural skills.

This lived complexity is visible in the text and the illustrations that depict her daily life. For example, her family are depicted code-switching in the dialogue, ‘speaking Spanish, English and sometimes both’ (p. 8); Marisol’s physical appearance mixes brown skin with hair the ‘colour of fire’ (p. 4); her choices in dress, ‘But I love green polka dots and purple stripes’ (p. 6); the food she eats, ‘peanut butter and jelly burrito’ (p.16); her literacy lessons at school where she mixes cursive and print when writing her name (p. 10); she creates new playground games, ‘soccer-playing pirates’, as she fuses her friends’ different choices (soccer or pirates) into one game. Marisol lives in the hybrid, translanguaging space, where mixing and matching is how she makes sense of her world, how she expresses her linguistic and cultural identities. She is constantly reminded of this crossing of borders by the other characters as they repeat that Marisol ‘doesn’t match / no combina’. This reflects an awareness of, an engagement with, and a respect of difference, without erasing the distinctness and uniqueness of each of Marisol’s worlds. This is an act in disrupting and decentring the monolingual/monocultural habitus, where fluid, holistic multilingualism and intercultural exchanges are the norm.

An analysis of the mixing and matching of food, clothes, art, playground games and languages in this picturebook can lead to exercises that elicit children’s imaginative play and tap into the hidden diversity in the classroom: new recipes, artistic forms and language encounters can be invented with the resources readily available in children’s repertoires. These activities can lead to discussions of how cultures are products of intercultural encounters and exchanges. On a more personal level, the activity ‘The Pieces of You’, where children decorate puzzle pieces with unique aspects of themselves, encourages children to see themselves and their classmates as complex, multifaceted individuals. Only when the puzzle pieces come together can we see the whole child. This activity is freely available online on the ReaderKidz website, as part of a Marisol Activity Kit (Courtney, 2015, pp. 2-3).

This bilingual picturebook combines the translated text with translanguaging on pages 8 and 9 respectively, during the family’s conversation about buying a puppy:

‘Can I have a puppy? A furry sweet perrito?’ –¿Puedotenir un perrito? ¿Un puppy dulce ypeludito?

I ask my parents,‘Por favor?’ –lepido a mis padres–. Please?

Both the English and the Spanish text are interspersed with text from the other language. Hence translanguaging occurs equally across the two languages, with the texts mirroring each other across the double-page spread and the words in italics represent the language mixing. Punctuation conventions also characterize the different languages in this dialogue, quotation marks in English versus dashes in Spanish to introduce dialogue. However, authentic language use is evident as Marisol’s anglophone father and Spanish-speaking mother’s comments are not translated. The author keeps them in their linguistic roles:

‘Quizás,’ Mami says. –Quizás–dice mami.

‘Maybe,’ Dad says, smiling and winking. –Maybe–dice Dadsonriendo y guiñando.

Not only does this picturebook consolidate the close links between cultural and linguistic diversity, but it also emphasizes the more nuanced trans-linguistic aspect of multilingualism.

Having access to another language in the English classroom allows for a language(s) awareness approach. The teacher mediates the children’s discovery of different sounds, phrases, grammatical conventions and concepts, and highlights comparisons and differences between English and Spanish. Delving into languages invites discussions around the languages of the teacher (an often-forgotten element in the language classroom) and encourages metalinguistic discussions in relation to children’s other languages. However, in a context where both languages are present in the wider community and/or in the school, as second or foreign languages, a bilingual picturebook in the English classroom can act as a resource to support the learning of both languages.

This picturebook offers teachers a child-friendly artefact to develop children’s understanding of the complex, multidimensional and dynamic nature of multilingualism. For example, Marisol’s bilingual workbook on p. 6, which indicates her biliterate education, and the shopping list in Spanish on the fridge, which reflects the mother’s use of her L1, characterizes fluid multilingual communicative practices. It draws attention to the active use of translanguaging, which can be integrated into the teaching-learning cycle. In this way, children learn what it is like to be a plurilingual individual and relate multilingual practices in picturebooks to their own experience of multilingualism. This approach expands the children’s repertoire of discursive possibilities and offers them alternative and agentive tools for exploring their plurilingual identity. The interplay of the linguistic and visual landscape of multilingualism in the book foregrounds the dynamic and simultaneous multiplicity of multilingual living. It questions the myth of separate languages and allows for metalinguistic dialogue about multilingual communicative practices. It also includes a learning to learn to be plurilingual approach based on the following potential questions, which highlight noticing and personalising strategies:

How does Marisol mix her languages?

When does she mix her languages?

Who does she do it with?

Do you mix languages?

When and with whom?

What do you think of mixing languages?

Even though from a linguistic landscape perspective the English language seems to predominate, as it is the first text to appear on each double spread, there is an attempt to ensure an equal balance of English and Spanish in the book. There are also newspaper cuttings in Spanish throughout the book, appearing in different forms and shapes, for example the teacher’s skirt on p. 11, the football and birds on p. 12, the football again on p. 21. These elements of extra Spanish balance out the initial and perceived overwhelming presence of English. This Spanish presence is in the background, subtly yet constantly present, not hidden but ignored at first, which is very often what plurilingual children experience in schools.

Marisol manages her plurilingual identity between the linguistically different contexts of the home and the school and the negative impact of monolingualizing practices and attitudes, represented by her friends and classmates, on her wellbeing. Agency is an important theme in this book as Marisol is shown making all the decisions about how she prefers to live her life. Hence, it is not surprising that the choice to start ‘matching’, the climax in the narrative, is Marisol’s, goaded by a friend’s comment: ‘Marisol, you couldn’t match if you wanted to!’ (p. 16). This moment represents the power of language to label and delegitimize Marisol’s complex identity and exemplifies the pressure that plurilingual children undergo by their peers, the adults in their entourage, and society in general, to conform to the monocultural and monolingual world view. Even though Marisol makes the decision ‘to match’ herself, the negative consequences on her well-being, her personality, her mood and her creativity are evident in the second half of the book. The consequences of repressing her plurilingual identity are paralysing as she becomes an inactive shadow of herself.

The tension between affirming her identity and conforming to particular cultural norms is resolved by the teacher’s revelation of her own multiple self. Marisol’s teacher reveals her Japanese-American identity in a note to Marisol, which she signs off with her Japanese first name, Jamiko. Her teacher’s acceptance of Marisol’s complex identity and the subtle revelation of her own cultural hybridity reassures Marisol that she is not alone. The teacher’s action positions adults, in this case, the teacher, as a potential mirror of multilingualism and interculturality. Furthermore, the author, Monica Brown, reads aloud the picturebook in English and in Spanish (Brown, 2020) in separate readings, maintaining the translanguaging instances. This further reinforces the multilingual lens and provides the teacher with authentic language input.

Even though Marisol surprises, and perhaps annoys her friends and teacher at school, this multiple, fragmented, kaleidoscopic approach to life is celebrated in this picturebook. The different multicoloured threads of Marisol’s, and other bicultural children, are interwoven expertly by the choices Marisol makes. Her choice of puppy or perrito at the end of the book further strengthens and consolidates the normality of Marisol’s multilingual living. Not only is the puppy ‘mismatched and simply marvellous, just like me’, but she decides to name him ‘Kitty’. Ultimately, the message of acceptance of difference, tolerance of ambiguity and inclusion permeates the narrative, the visual vibrancy of the illustrations and Marisol’s existence in the in-between spaces of the multilingual-multicultural nexus.

Discussion and Conclusion

Demonolingualizing the EFL classroom, by including multilingual literature, constitutes an active choice to disrupt and decentre the monolingual status quo. The languages that exist in picturebooks should not be glossed over or ignored, but actively integrated into the planning and teaching process of English as well as of cross-curricular and global issues. A multilingual focus through picturebooks challenges perceived monolingual norms and the compartmentalization of languages and can develop the following aspects of the multilingual-multicultural nexus:

- It fosters multilingual awareness and foregrounds fluid translingual communicative practices;

- It develops intercultural and transknowledging skills that engage students’ multiple meaning making systems and subjectivities;

- It instigates a critical review of the overly whitewashed (Gerald, 2020), univocal world of the English classroom.

Using multilingual picturebooks in the ELT classroom presents certain difficulties that need to be acknowledged. First and foremost, there are the practicalities of finding appropriate multilingual picturebooks, as there is currently a dearth of books that integrate other languages in the narrative. When they do exist, they may be so specific to particular linguistic contexts that they are not always available to a wider audience. For example, my experience of attempting to purchase the Māori-English picturebook, Koro’s Medicine (Drewery, 2004), was unsuccessful as the book was unavailable or impossible to ship to Europe from New Zealand.

Kümmerling-Meibauer (2013) notes that ‘even if children’s novels include passages written in a second language, translations into other languages often veil the original text’s multilingual structure by translating the whole text into the target language’ (p. vi). One case in point, in the 21st century, is the European edition of Julián is a Mermaid (Love, 2018). This picturebook is described by Love on her website as ‘a story about revealing ourselves, and the beauty of being seen for who we are by someone who loves us’. In this case, Julián has an Afro-Carribean, Spanish-speaking grandmother, whom he refers to as abuela in the text, hence Julián’s Spanish-speaking identity is part of the beauty of who he is. However, this originally interlingual book, where some Spanish words are interspersed in the English base text, has been completely ‘translated’ into a monolingual English text in the UK by Walker Publishing, sanitized of foreign influences or linguistic interference. Even Julián’s name, with the omitted accented ‘á’, has lost its specific cultural flavour.

Another consideration is deciding on which languages to choose for a particular teaching context and the instructional purpose, that is, language awareness, language teaching or multilingual-multicultural awareness. For the latter, it is imperative for teachers and the educational establishment to view language education through the multilingual lens. This entails training in understanding the value of multilingualism for extending intercultural learning. I would, therefore, encourage further research into the picturebook as an artefact in the multilingual-multicultural nexus. Furthermore, research into selecting and using bilingual picturebooks with teachers and children in real EFL classrooms would capture their voices and reflections on a language-conscious learning experience, while acknowledging language and cultural diversity.

Exploring the mirrors and windows (Bishop, 1990, ix) and the linguistic landscape of picturebooks can lead to more inclusive practices in ELT. It should question the use of exclusively English-language books and the appropriateness of English to represent every culture, when attempting to teach interculturality. It acknowledges the existence of multiple languages in society, and the classroom. It encourages disclosure, discussion of, and reflection on the multilingual phenomenon, and normalizes translingual practices in teaching and learning. An intercultural English lesson thus becomes a trampoline for critical discussions about cultural and linguistic diversity, making languages visible, welcome and a factor in children’s well-being.

Bibliography

Anzaldúa, G. (1995). Friends from the Other Side/Amigos del Otro Lado. C. Méndez (Illus.) San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

Brown, M., Palacios, S. (illus.) & Domingues, A. (trans.) (2011). Marisol MacDonald Doesn’t Match / Marisol MacDonald no combina, New York: Children’s Book Press.

Brown, M. (2020, 7 April). Lee & Low Storytime: Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match, read by Monica Brown | Picture Book Read Aloud. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fzl_ynrAglQ

Brown, M. (2020, 9 April). Cuentacuentos: Marisol McDonald no combina, leidopor Monica Brown | Spanish Read Aloud Books: Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Frd86BfM1eA

Drewery, M. (2004). Koro’s Medicine. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Garland, S. (2012). Azzi in Between. London: Francis Lincoln Children’s Books.

Love, J. (2018). Julián is a Mermaid. Candlewick Press

Ngozi Adichie, C. (2009). The danger of a single story. TEDGlobal. Retrieved from: https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

References

Applegate, A. J. & Applegate, M. D. (2004). The Peter Effect: Reading habits and attitudes of preservice teachers. The Reading Teacher, 57 (6), 554-563.

Bergner, G. (2016). Azzi in Between – A bilingual experience in the primary EFL classroom. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 4 (1), 44-58.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture, Abingdon, Routledge.

Bland, J. (2020). Using literature for intercultural learning in English language education. In M. Dypedahl & R. Lund (Eds.), Teaching and Learning English Interculturally. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, pp. 69-89.

British Council, (2013). The English Effect: The Impact of English, What It’s Worth to the UK and Why It Matters to the World. UK: British Council.

Byram, M. (2008). From Foreign Language Education to Education for Intercultural Citizenship. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95 (iii), 401-417.

Cenoz, J. (2013). Defining multilingualism. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 33, 3-18.

Chevalier, S. (2015). Trilingual Language Acquisition: Contextual Factors Influencing Active Trilingualism in Early Childhood. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Cotton, P. & Daly, N. (2015). Visualising cultures: The ‘European Picture Book Collection’ moves ‘down under’. Child Lit Educ, 46, 88-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-014-9228-9

Copland, F. & Neokleous, G. (2011). L1 to teach L2: complexities and contradictions. ELT Journal, 65 (3), 270-280.

Copland, F. & Ni, M. (2018). Languages in the young learner classroom. In S. Garton & F. Copland (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Teaching English to Young Learners, Abingdon, UK: Routledge, pp. 138-153.

Council of Europe (2018). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Retrieved from: https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-newdescriptors-2018/1680787989

Courtney, L. (2015). Marisol Activity Kit. ReaderKidz. Available at: https://www.readerkidz.com/2011/11/22/marisol-mcdonald-doesnt-match-by-monica-brown/

Daily Sabah (2020). Student in Germany punished for speaking Turkish. Daily Sabah, July 15. Retrieved from: https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/student-in-germany-punished-for-speaking-turkish/news

Daly, N. (2014). Windows between worlds: Loanwords in New Zealand children’s picture books as an interface between two cultures. In C. Hélot, R. Sneddon, & N. Daly (Eds.), Children’s Literature in Multilingual Classrooms: From Multilliteracy to Multimodality, London, England: Trentham Books Limited, pp. 35-46.

Daly, N. (2018). The linguistic landscape of English–Spanish dual language picturebooks, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39 (6), 556-566.

Daly, N. (2019a). The relative silence of languages in multilingual picturebooks. In Silence and Silencing in Children’s Literature. IRSCL Congress 2019. Stockholm, Sweden.

Daly, N. (2019b). Translanguaging in dual language Māori-English picturebooks. In Translanguaging Aotearoa 2019 Symposium. Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand.

Dervin, F. (2010). Assessing intercultural competence in language learning and teaching: A critical review of current efforts in higher education. In F. Dervin & E. Suomela-Salmi (Eds.), New Approaches to Assessment in Higher Education, Berne, Switzerland: Peter Lang, pp. 157-174.

Dervin, F. & Gross, Z. (2016). Intercultural Competence in Education: Alternative Approaches for Different Times. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dolan, A. M. (2014). You, Me and Diversity: Picturebooks for Teaching Development and Intercultural Education. London: Trentham Books.

Dooly, M. & Vallejo, C. (Eds.). (2018). Bridging across languages and cultures in everyday lives: An expanding role for critical intercultural communication [Special issue]. Language and Intercultural Communication, 18 (1), 1-8.

Driscoll, P. & Simpson, H. (2015). Developing intercultural understanding in primary schools. In J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 Year Olds. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 167-182.

Duarte, J. & Günther-van der Meij, M. (2018). A holistic model for multilingualism in education. EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages, 5 (2), 24-43.

Ellis, G. (2010). Promoting Diversity through Children’s Literature. London: British Council. Retrieved from: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/promoting-diversity-through-children%E2%80%99s-literature [story notes on Is it Because?, Susan Laughs, What if?, Little Beauty, The Very Busy Spider, Tusk Tusk, Rain, Peas!].

Ellis, G. & Brewster, J. (2014). Tell It Again! The Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers (3rd ed.). London: British Council. Retrieved from: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/tell-it-again-storytelling-handbook-primary-english-language-teachers

Ellis, G. & Ibrahim, N. (2015). Teaching Children How to Learn. Peaslake: Delta Publishing.

Enever, J. (2018). Policy and Politics in Global Primary English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

European Commission (2011). Language Learning at Pre-Primary School Level: Making it Efficient and Sustainable: a Policy Handbook. Commission Staff Working Paper, ET2020. Brussels: EC.

European Union (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006H0962&from=EN

European Union (2019). Key Competences for Life-long Learning. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/297a33c8-a1f3-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Freire, P. & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. London: Bergin & Garvey.

Galda, L. & Callinan, B. E. (2002). Cullinan and Galda’s Literature and the Child. Belmont: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

García, O. & Li W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gerald, J. P. B. (2020). Worth the risk: Towards decentring Whiteness in English language teaching. BC TEAL Journal, 5 (1), 44-54.

Graddol, D. (2006). English Next. Why Global English May Mean the End of ‘English As a Foreign Language’. UK: British Council.

Ghosn, I. (2002). Four good reasons to use literature in primary school ELT. ELT Journal, 56 (2), 172-179.

Hall, G. (2010). Exploring values in English language teaching: Teacher beliefs, reflection and practice. The Teacher Trainer Journal, 24 (2), 13-16.

Heller, M. (2012). Rethinking sociolinguistic ethnography: From community and identity to process and practice. In S. Gardner & M. Martin-Jones (Eds.), Multilingualism, Discourse and Ethnography. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 24-33.

Heggernes, S. L. (2019). Opening a dialogic space: Intercultural learning through picturebooks. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 7 (2), 37-60.

Heugh, K. (2018). Conclusion: Multilingualism, diversity and equitable learning: Towards crossing the ‘abyss’. In N. P. Van Avermaet, S. Slembrouck, K. Van Gorp, S. Sierens & K. Maryns (Eds.), The Multilingual Edge of Education. UK: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 341-367.

Heugh, K. (2019). Translanguaging cautiously: Keeping multilingualism, transknowledging and purpose in balance or: From EAL/D and TESOL to EMI in a multilingual world. Presentation at the Tasmanian Association of TESOL Teachers’ Conference: Working in Multilingual Communities & Classrooms, 11 May, Hobart.

Hopp, H., Jakisch, J., Sturm, S., Becker C. & Thoma, D. (2020). Integrating multilingualism into the early foreign language classroom: Empirical and teaching perspectives. International Multilingual Research Journal, 14 (2), 146-162.

Husband, T. (2019). Using multicultural picture books to promote racial justice in urban early childhood literacy classrooms. Urban Education, 54 (8), 1058-1084.

Huyck, D. & Dahlen, S. P. (2019, June 19). Diversity in Children’s Books 2018. Blog sarahpark.com. Created in consultation with E. Campbell, M. B. Griffin, K. T. Horning, D. Reese, E. E. Thomas & M. Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp. Retrieved from: readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic

Kerr, P. (2014). Translation and Own-language Activities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kersten, S. & Ludwig, C. (2018). Translanguaging and multilingual picturebooks: Gloria Anzaldúa’s Friends from the Other Side/Amigos Del Otro Lado. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 6 (2), 7-27.

Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2013). Multilingualism and children’s literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 51 (3), iv-x.

Landry, R. & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality. An empirical study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16 (1), 23-49.

Ibrahim, N. (2014). Perceptions of identity in trilingual 5-year-old twins in diverse pre-primary educational contexts. In S. Mourão & M. Lourenço (Eds.), Early Years Second Language Education: International Perspectives on Theories and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 46-61.

Ibrahim, N. (2019). The right to my languages: Multilingualism in children’s English classroom. TEYLT Worldwide, Issue 1, IATEFL YLTSIG Publication. Faversham: IATEFL, pp. 27-31.

Ibrahim, N. (in press). Artefactual narratives of multilingual children: Methodological and ethical considerations in researching children. In A. Pinter & H. Kuchah (Eds.), Ethical and Methodological Issues in Researching Young Language Learners in School Contexts. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters

Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a Lingua Franca: Attitude and Identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mesthrie, R. & Bhatt, R. M. (2008). World Englishes: The Study of New Linguistic Varieties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ministry of Education and Training. (2019). Core curriculum – Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education (Overordnet del – verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen). Oslo: Norwegian Government. Retrieved from: https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/

Ministry of Education and Training (2020). Læreplan i engelsk ENG01-04 (Curriculum for English). Oslo: Norwegian Government. Retrieved from: https://www.udir.no/lk20/eng01-04

Ministry of Education and Training. (2020). Læreplan i fremmedspråk (FSP1-01) (Curriculum for Foreign Languages). Oslo: Norwegian Government. Retrieved from: https://www.udir.no/kl06/fsp1-01/

Mourão, S. (2015). The potential of picturebooks with young learners. In J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 Year Olds. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 199-217.

Naqvi, R. Thorne, K. J., Pfitscher, C. M., Nordstokk, D. W. & McKeoughat, A. (2013). Dual-language books as an emergent-literacy resource: Culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 11 (1), 3-15.

Oliver Smith, A. (2020, 12 July). Sweden referred to European Court of Human Rights over alleged discrimination of Finnish-speaking children. Helsinki Times. Retrieved from: https://www.helsinkitimes.fi/finland/news-in-brief/17851-sweden-referred-to-european-court-of-human-rights-over-alleged-discrimination-of-finnish-speaking-children.html

Pennycook, A. (2012). Language and Mobility: Unexpected Places. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Porto, M. (2019). Affordances, complexities, and challenges of intercultural citizenship for foreign language teachers. Foreign Language Annals, 52, 141-164.

Robles de Melendez, W. & Ostertag, V. (2010). Teaching Young Children in Multicultural Classrooms: Issues, Concepts, and Strategies (3rd ed.). Wadsworth: Cengage Learning.

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 1 (3), ix-xi.

Short, K. (2011). Reading literature in elementary classrooms. In S. Wolf, K. Coats, P. Enciso & C. Jenkins (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Children’s and Young Adult Literature. New York: Routledge, pp. 48-62.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2000). Linguistic Genocide in Education – or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Mahwah, NJ & London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

UNCRC (1989). The Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva: United Nations.