| Opening a Dialogic Space: Intercultural Learning through Picturebooks

Sissil Lea Heggernes |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This study discusses how knowledge of dialogic features can inform intercultural learning. Intercultural learning is highlighted in educational policy as a means of managing cultural diversity (for example, Council of Europe, 2018). Furthermore, intercultural dialogue is a frequently employed term. However, the features and aims of intercultural dialogues often remain vague. To help elucidate them, secondary-school students’ conversations about a picturebook in the ELT class are analysed through the lens of dialogic theory (Alexander, 2008; Mercer & Howe, 2012; Vrikki, Wheatley, Howe, Hennessy, & Mercer, 2019; Wegerif, 2011). Through engaging with the pictures, a dialogic space emerged, allowing the students to display curiosity about another culture and contribute ideas. Their willingness to actively listen, explore conflicting ideas and change their minds led to joint meaning-making and the co-construction of knowledge of another culture (Byram, 1997; Deardorff, 2006). The study adds to the scarce empirical literature on reading for intercultural learning in English language teaching (ELT) (Hoff, 2017) through its novel approach, applying dialogic theory to intercultural learning, mediated by picturebook dialogues. I argue that knowledge of dialogic features can serve as a tool for teachers aiming to foster students’ intercultural learning in ELT.

Keywords: dialogic education; intercultural learning; picturebooks; English language teaching; lower-secondary level; The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain

Sissil Lea Heggernes is a PhD candidate at Oslo Metropolitan University with extensive teaching experience from primary and secondary schools. In her research, she explores how challenging picturebooks can foster English language students’ intercultural communicative competence (ICC). [end of page 37]

Introduction

Dialogue is a term that has gained much currency over the last decade, frequently preceded by the adjective ‘intercultural’. Its usages can be divided into two strands: (a) intercultural dialogue as a response to globalization in order to manage increased cultural diversity (for example, Council of Europe, 2008; UNESCO, 2013) and (b) dialogue as an approach to intercultural learning through dialogic activities, and/or readers’ dialogue with text representing the readers’ own or another culture (Byram & Wagner, 2018). It is the latter usage that is of interest in this paper. The terminology of dialogue can vary, with the word sometimes used interchangeably with words such as ‘discussion’, ‘interaction’ and ‘talk’ and often used loosely, leaving the specific features and aims of dialogue undefined. This paper will focus on what makes classroom talk dialogic and how dialogues can foster intercultural learning. To this end, the following research questions are addressed:

- What features of dialogue seem to be conducive to intercultural learning?

- How might teachers facilitate students’ intercultural dialogues?

These questions are explored through the lens of secondary-school students’ intercultural dialogues about a picturebook in the ELT class, applying insights from dialogic theory (Alexander, 2008; Mercer & Howe, 2012; Vrikki et al., 2019; Wegerif, 2008, 2011; Wegerif & Mercer, 1997). I argue that knowledge about dialogic features and aims can advance our understanding of how students’ intercultural learning is mediated through interaction with text and with other readers. Little empirical research has been done on reading practices for intercultural learning in ELT (Hoff, 2017, p. 2), especially related to learners in lower-secondary education. Hence, this study adds to the scarce literature on the topic. It can also provide support for teachers’ development as intercultural educators.

Theoretical Background: Intercultural Learning, Dialogue and Picturebooks

Intercultural learning can be defined as the development of knowledge, skills and attitudes needed for effective and appropriate communication and behaviour ‘when interacting across difference’ (Deardorff, 2019, p. 5). Some commonly agreed-upon elements include curiosity and discovery, cultural knowledge, perspective-taking skills, critical cultural awareness, listening skills, empathy and adaptability (Deardorff, 2006; Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009). [end of page 38]

According to Delanoy, dialogue encompasses interculturality. His concept of dialogic competence shares similarities with models of intercultural competence, such as curiosity, critical awareness and perspective-taking skills (Byram, 1997; Delanoy, 2008). Dialogue involves recognition of and sincere interest in the others’ perspectives. Wegerif translates the Greek ‘dialogic’ into ‘meaning emerging from the interplay of different perspectives’ (2011, p. 180). We need others’ perspectives on us to see ourselves more clearly and to develop perspective-taking skills and empathy (Dysthe, 2013). Through dialogue, in the Socratian sense, the participants may be moved from expressing their doxa – their beliefs and perceptions – to expressing episteme, knowledge tested through questioning and justifying (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2008, pp. 34-39). Both forms of knowledge are relevant to this qualitative study. In practice, a dialogic classroom culture entails giving students agency to contribute and explore ideas and constructively challenge and build upon those of each other (Alexander, 2008).

Fiction is suitable for intercultural learning, as literature may help readers engage with conflicting perspectives (Hoff, 2014). Readers engage in their own and other cultures through literature, and this engagement may foster intercultural learning (cf. Bredella, 2000; Bredella & Delanoy, 1996; Fenner, 2001; Hoff, 2017; Kramsch, 1993; Matos, 2005). Picturebooks may add another layer to the intercultural reading experience. According to Hallberg, a picturebook is a book that has a minimum of one picture per double spread (1982). The pictures can replicate, expand and contradict the verbal text (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006). Through readers’ engagement with the semiotic meaning of the picture-text relationship (Evans, 2013), they can discover and critically analyse the multiple voices and ideologies represented in the narrative (Stephens, 2018).

The Features and Aims of Dialogues

Wegerif and Mercer divide student-student talk into three types: disputational, cumulative and exploratory (2013; 1997; italics mine). Disputational talk entails competing to find the correct solution in order to win an argument. In cumulative talk, students build on each other’s ideas. Though all voices are heard, ideas are not challenged and explored. Differences in opinion might be glossed over or ignored in order to maintain the harmony of the group (Wegerif, 2008, 2011). The most educationally productive talk occurs when [end of page 39] groups share ideas, which are explored, constructively criticized and built upon, especially when students are willing to change their mind if they are wrong (Wegerif, 2008, 2011). These are the characteristics of exploratory talk. Considering studies of student-student and student-teacher talk, Wegerif finds that it is not merely the characteristics of exploratory talk that help groups develop their thinking, but also identification with the aims of the dialogue itself (Wegerif, 2011, p. 184). Therefore, he prefers the term dialogic talk, which entails ‘an openness to the other and respect for difference’ (2011, p. 184). These are also elements of intercultural learning.

Summing up the most prominent research on dialogue, Vrikki et al. conclude that the ‘participative ethos […] with participants respecting and listening to all ideas’ (Vrikki et al., 2019, p. 86) is essential for productive classroom dialogue. These qualities are fundamental to student ‘identification with the dialogue’ (Wegerif, 2011), and require a supportive and inclusive classroom culture. Furthermore, the teacher plays an important part in facilitating student dialogues. This includes helping students co-ordinate and synthesize ideas, activities which are lacking in many classrooms (Vrikki et al., 2019).

Intercultural Dialogue

If intercultural dialogue involves ‘interacti[on] across difference’ (Deardorff, 2019, p. 5), what is the aim of dialogic interaction? Outlining a theoretical dichotomy, the aim of dialogue can be:

1. reaching agreement and/or mediating contrasting views

or

2. learning to tolerate ambiguity and live with conflict.

Littleton and Mercer hold that attempts to reach agreement are an important feature of educational dialogues, as they can push the students to explore each other’s ideas more carefully even if they do not manage to reach agreement (Littleton & Mercer, 2013, p. 38). Similarly, Byram (1997) stresses the ability to mediate different perspectives as essential for intercultural communicative competence.

Wegerif, for his part, states that agreement is only one point on a fluid continuum (Wegerif, 2011, p. 182). According to Delanoy, ‘irritation and contradiction’ may enhance one’s reflective skills (Delanoy, 2008, p. 177). Hoff (2014) takes up this thread when she [end of page 40] criticizes Byram for focusing too strongly on harmonizing contrasting views. She reads his model as reminiscent of Hegel’s dialectic: thesis – antithesis – synthesis, in which difference is overcome in a dialectic dialogue and the ultimate goal is to understand the other’s position. In today’s pluricultural world, we should rather learn to tolerate ambiguity, as ‘[c]onflict, ambiguity and difference [are] not solely […] challenging aspects of the intercultural encounter, but […] potentially fruitful conditions for profound dialogue between Self and Other’ (2014, p. 208).

This study will exemplify not only how exploration of conflicting views may lead to intercultural learning but also how other dialogic features serve to drive dialogues forward. I argue that this may happen when a dialogic space is created, a ‘dynamic continuous emergence of meaning’ in which students solve problems through listening, requesting help, ‘changing their minds [and] seeing the problems as if through the eyes of others’ (Wegerif, 2011, p. 180).

Previous Research

Studies from a range of fields have considered how dialogic education might develop students’ cognitive and emotional skills, which have been seen as constituent skills of intercultural learning (Maine, 2013; Rojas-Drummond, Mazon, Fernandez, & Wegerif, 2006). However, the link between such development and intercultural learning is not necessarily targeted, and dialogic approaches to intercultural learning in primary and lower secondary ELT is an understudied field. In this section, I will comment on a few studies relevant to my own, concerned with either literary dialogues (talking around stories) and/or intercultural learning from first- and second-language classrooms.

Mourão (2013), Yeom (2019) and Hoff (2017) studied secondary-school ELT classrooms. Mourão (2013) reveals the potential of discussions about multimodal texts for developing student vocabulary and critical engagement through interthinking (Littleton & Mercer, 2013). Yeom (2019) discusses visual grammar in teenagers’ discussions of picturebooks. Through a thematic analysis, she shows how the teacher facilitates the discussion and how ‘aspects of global awareness’ are developed (2019, p. 1). Hoff’s (2017) concern is how teachers can foster intercultural readers. She offers a theoretical model to capture ‘the communicative processes [of the] “intercultural reader”’ (Hoff, 2017, p. 4). Nonetheless, Hoff recognizes that teachers require a high level of intercultural competence [end of page 41] to transform conflictual encounters into intercultural learning experiences (2019, pp. 106-109).

Wiseman (2011) and Pantaleo (2007) analyse the discourse features of literary dialogues in first-language primary classrooms, and Maine shows how empathy stimulates children’s dialogues (2013). The studies above exemplify how dialogic transactions with literature, including multimodal texts, may foster skills conducive to intercultural learning, such as empathy and critical engagement. The present study adds to this research. Applying insight from dialogic theory to intercultural dialogues, I aim to link knowledge of dialogic features to intercultural learning through picturebooks in secondary-school ELT. I suggest that knowledge of dialogic features and of how to mediate them might help teachers transform student reading experiences into intercultural learning.

The Intercultural Picturebook Project

The Learners and the Teacher

The dialogues are collected from a case study in a small Norwegian town, where an eighth grade ELT class read Peter Sís’ graphic memoir, The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain (2007). The group comprised twenty-three 13- and 14-year-olds. Norwegian students study English in class for one to two hours per week from first grade, increasing to two hours from eighth grade. The students’ language skills ranged from A2 to B1 level in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). According to the teacher, the students were accustomed to small-group discussions, and the whole-class discussions that I observed were carefully guided by the teacher. In preparation for the project, the teacher and I discussed the importance of allowing the students to make their own interpretations. Accordingly, I encouraged the teacher to use open-ended questions and to emphasize that there were no right or wrong answers.

The focus on intercultural learning entailed targeting both cognitive and emotional skills. Through triggering the students’ curiosity, the aim was to increase their knowledge of another culture, encompassing both historical learning and understanding of social interaction and fostering perspective-taking skills – all significant elements of intercultural competence (Byram, 1997; Deardorff, 2006; Wagner, Perugini & Byram, 2018). Moreover, [end of page 42] tolerance of ambiguity came into play, as reading this book represented a threefold intercultural experience for the students:

- The picturebook represented an unconventional choice of text. None of the students had read a picturebook since early in primary school, and they considered this as literature for small children only.

- The book represented an unknown culture. The class had almost no knowledge of communism, and several students were unaware that Czechoslovakia had existed as a nation state.

- Reading literature in a foreign language is in itself an intercultural experience (Bredella & Delanoy, 1996; Fenner, 2001; Hoff, 2017).

The Picturebook and the Activities

The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain

This book (see Figure 1) is a hybrid picturebook/graphic novel. It utilizes a combination of media and modes, such as illustrated double-spreads, maps, photos, panels, journal excerpts, and factual and narrative text to relate Sís’ story of growing up during the Cold War in Czechoslovakia. He describes how he and his peers were, in his words, brainwashed by the system, but also how, as he grew older, ‘Western music made a crack in the wall’ and he began to question what he had been taught (Sís, 2007, unpaginated).

Figure 1. Cover, Peter Sís (2007) The Wall. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. [end of page 43]

Activities

The students worked with the book over five sessions. I created activities aiming to foster their intercultural learning, which were subsequently approved and carried out by the language teacher. Starting with pre-reading activities, the students built up schemata about the geographical and ideological setting. Then followed a shared reading of the historical introduction and the captions at the bottom of the page, narrating Peter’s story, including time to discuss the pictures. Through open-ended questions, the teacher encouraged the students to share their perceptions. An activity with the teacher-in-role as Peter Sís allowed the students to ask ‘the author’ questions. Furthermore, the post-reading activities focused on whole-class and small-group dialogues about their interpretations of the book, allowing them to draw on their own experiences.

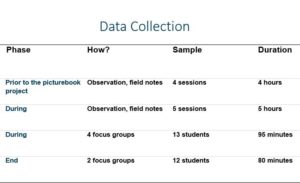

Researcher Role, Data Collection and Analysis

I observed four sessions but had to teach one due to the teacher’s absence. Hence, I alternated the roles of outside and participant observer (DeWalt & DeWalt, 2011). In the focus group interviews, I talked to 12 students in total, all of whom, and their parents, had signed consent forms. Table 1 illustrates the sequence and forms of data collection. While this project is part of a larger study, this article focuses on focus-group dialogues and examples of classroom talk, analysed through the lens of dialogic theory (Alexander, 2008; Vrikki et al., 2019; Wegerif, 2011). These serve as illustrations of intercultural learning through picturebook dialogues, without making any broad generalizations.

Table 1. Data Collection [end of page 44]

The focus groups gathered after every session. The focus group was chosen to accommodate an exchange of multiple viewpoints and gain deeper insight into the students’ learning than was possible through classroom observation alone (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009, p. 150). A semi-structured interview guide was used, consisting mainly of open-ended questions to encourage dialogue. The audiotaped interviews were transcribed verbatim using a transcription key modelled on the Jefferson (1984) notation. I told the students that there were no right or wrong answers and that my only concern was to glean what they had learned and their opinions about the book and the activities. The interviews took place in Norwegian. This was the shared language mastered best by everyone involved and allowed the students to relax and express themselves more easily.

The students both applauded and criticized the project, indicating that they felt comfortable sharing their true opinions. However, as an adult, I should not overlook the unequal power relations in conversations with minors (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p. 94) and how my presence might have affected the students’ engagement (Steen-Olsen, 2010). The students came to know me as an observer in the classroom but quickly came to treat me as a second teacher. In the focus groups, I took on a dual role. As a researcher, I asked questions to capture the research object: examples of dialogic interactions and the students’ intercultural learning. However, I also considered it my ethical obligation to give something back to the participants by facilitating their learning (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p. 94). Hence, in the example dialogues, I often took on the role of teacher, aiming to facilitate students’ educational dialogues. As such, the focus-group interactions can serve as examples of what could have happened in the classroom.

In the following sections, I will analyse dialogues from two focus groups, each with six students, and examples of classroom talk from the same project. They have been sampled according to the following criteria:

- Chronology. The dialogues took place in focus groups after the final session. They are compared with classroom talk from the first session. This allows a contrast between the first session in a large group, when the students had little or no background knowledge, and dialogues about familiar content in a small group and might indicate progression in the students’ learning. [end of page 45]

- Length. The longest dialogues about illustrations were selected to allow analysis of the development of the students’ ideas.

- Consideration of dialogic features. Dialogues containing multiple features of educational dialogue were chosen to illustrate the possibilities of fostering intercultural learning through dialogic reading of picturebooks and contrasted with classroom talk.

The analysis focuses on the features below, from my review of dialogic theory. The features closely resemble the overview of dialogic features (Vrikki et al., 2019) shared by the most prominent research in the field. However, through an abductive process, I have adjusted Points 3 and 5, excluded points irrelevant to the dialogues in this study and included relevant points (2 and 6, respectively) from Alexander (2008) and Wegerif (2011).

- Invitations that provoke thoughtful responses, such as authentic questions, requests for clarifications and explanation.

- Agency, students initiating discussion through contributing new ideas.

- Building on each other’s ideas, through adding new points (extending).

- Challenging ideas constructively.

- Justifying ideas.

- Change of mind.

- Attempts to reach consensus.

- Display of a participative ethos, such as recognizing/valuing each other’s contributions.

In the following sections, I will first discuss some examples of classroom talk from the first session of this project. Second, I will carefully analyse one dialogue, then give a briefer account of two others, all from the final focus groups. [end of page 46]

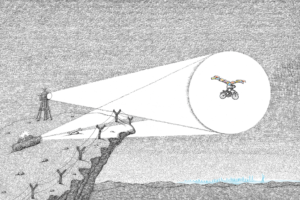

Classroom Talk

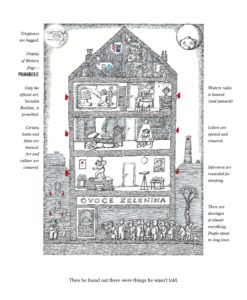

Figure 2. Illustration from Peter Sís (2007) The Wall. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Reprinted with permission of the author, © Peter Sís.

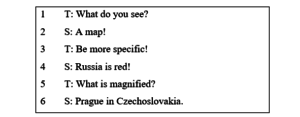

The following examples of classroom talk illustrate some of the challenges of whole-group dialogues in which the students have limited background knowledge on the topic. Following [end of page 47] my instructions, the teacher read the book to the students and tried to ask open questions about the pictures, allowing everyone to share their perceptions. While looking at the map on the endpaper, the teacher (T) asked the students:

Table 2. Classroom Talk about the Front Endpaper

The teacher’s question (1) opened the floor but received a matter-of-fact response. Accordingly, he probed for more information. His invitation elicited further factual information, and the interaction did little to expand the students’ thinking.

Cumulative talk is frequent in classrooms (Littleton & Mercer, 2013; Wegerif & Mercer, 1997), and this was demonstrated when the teacher asked the students what they saw in a picture and the students took turns to answer: ‘red flags’, ‘star’, ‘cards’, ‘drawing on the ground’ and ‘a kid‘. Cumulative talk allows everyone to participate and can be useful to get many ideas on the table. However, to expand the students’ thinking, the use of an open why-question can be more fruitful, as seen when the teacher asks the class to comment on a picture of a house (Figure 2) in Table 3.

Table 3. Classroom Talk about the Picture of the House in Figure 2 [end of page 48]

The teacher’s invitation first elicited merely factual information (Table 1). However, when he invited the students to reflect on reasons, several thoughtful responses emerged, reflecting knowledge of another culture (3 – 4). It should be mentioned that Student 7 (S7) was the only student in the class with pre-knowledge of communism. It is reasonable to presume that he drew on this knowledge in his response (4). S9 noticed a recurrent feature, but the comment was not followed up, and the shared reading resumed.

Inviting thoughtful responses, the teacher’s question (2) allowed some students to move beyond literal interpretations (3, 4), and opened up the discussion for more active participation. Still, the dialogue ended after six turns. These examples illustrate the challenges of facilitating intercultural dialogue in larger groups with students with limited background knowledge and limited time to develop the dialogue. However, an open why-question elicited more responses than the closed what-questions in the first example in Table 2, and more of these might have moved the dialogue from cumulative to the exploratory or dialogic.

The Bike with Wings: An Intercultural Dialogue

Figure 3. Illustration from Peter Sís (2007) The Wall. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Reprinted with permission of the author, © Peter Sís. [end of page 49]

In the following dialogue in Focus Group A around the illustration in Figure 3, S1 – 5 are students, whereas I am the researcher/teacher (R/T). The dialogue arose after the students had been asked if anything had confused them about the book. Following a brief discussion, Student 1 (S1) exclaimed:

Table 4. Focus Group Dialogue about Figure 3 [end of page 50]

In the discussion in Table 4, S1 shows agency through initiating this dialogue. This is one of several instances where students raised questions they had pondered, indicating that the content had stirred their curiosity. He elaborates his point to justify why it would not have worked (1, numerical references to Table 4). Not only is his contribution self-initiated, it is also more extended than many other contributions. S2 adds ‘with books’, as the wings may resemble books, building upon S1’s initial idea. Subsequently, he challenges S1’s view: ‘[…] it would have been easy to come and get him again!’ (3). At this point, the dialogue could have developed into disputational talk, with each student trying to win the discussion, or the difference in opinion could have been glossed over, leading to cumulative talk. Instead, both S3 and I show that we value the contributions by saying ‘Good point!’ (2-3), helping the dialogue to proceed.

All the participants listen to each other, and I repeatedly utter ‘mmm’ or ‘yes’ to show that I am listening with interest. The laughter, relaxed atmosphere and overlapping comments (indicated as [ in the transcription) underline the participative ethos of all the participants, encouraging the student to continue and elaborate. S1 justifies his argument (4) and makes a counter-challenge to S2’s contribution, maintaining a very literal interpretation of the picture, typical of an early stage of reading development (Appleyard, 1991, pp. 28-29).

However, now he is challenged by S4, who sees a metaphor (5). I recognize S4’s contribution and invite her to explain what she means (6). The next comment (7) is difficult to hear. S4’s hesitant laughter prompts S5 to build upon her contribution: ‘when he’s drawing, he’s free’ (8). My response (9) shows that I value this contribution. Nonetheless, S1 still struggles to let go of his original idea. He now refers to what is ‘written’ (10), when in fact this is his literal interpretation of a picture (the verbal text has no mention of planes). Then it strikes him that the verbal text on these spreads do not mention the US. The allusions to the US are only visible in the pictures. Subsequently, I challenge the group, but implicitly S1, querying: ‘Eh, do you think that’s how he got to the US?’ (11). His answer shows a willingness to change his mind (12), indicating identification with the dialogue (Wegerif, 2011). He recognizes that the protagonist probably travelled to the US by other means and offers another, more realistic interpretation. [end of page 51]

Inviting thoughtful responses was not always successful. Following the dialogue above, I invited more reflections on what might have happened by showing the students Sís’ illustration of various ways to escape (2007, np) and asking an open question: ‘What do you see here?’ When the students failed to relate the illustration to Peter (the author), I explained how Peter Sís really came to the US. This was a missed opportunity for a dialogue about the events and indicates that I was probing for one specific answer all along. It is also possible that my attempts at valuing the students’ contributions through utterances such as ‘Good point!’ and ‘Good thinking!’ (2 & 6) were interpreted as evaluative statements by the students. Consciously or not, this might have led to a search for ‘correct’ answers, making the dialogue fit into the pattern of a dialectic dialogue: thesis – antithesis – synthesis, rather than dialogic talk (Wegerif, 2011, p. 184).

Nonetheless, the dialogue displays all the signs of an educational dialogue indicated in the previous section. The group moved from a literal interpretation to a metaphorical understanding of the image, co-constructing cultural knowledge. This process requires co-ordination of ideas, synthesizing the knowledge of the culture and the individual, gained through the narrative, to arrive at a metaphorical interpretation. These dialogic forms can lift the students’ reasoning to a higher level (Vrikki et al., 2019) and be conducive to intercultural learning.

Elements of intercultural learning such as curiosity and discovery, cultural knowledge, listening skills and adaptability (Deardorff, 2006; Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009) are intertwined with the italicized features of dialogue in this excerpt. The student’s curiosity about the picture prompts the dialogue to proceed through challenges, justifications and elaborations, which allows for discovery and creation of cultural knowledge. Furthermore, S1’s willingness to change his mind indicates an ability to see other perspectives. The teacher can facilitate this process by inviting thoughtful responses and asking open questions which require justifications, while resisting the urge to provide answers.

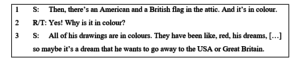

Intercultural Dialogues about the House Picture

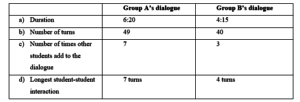

At the end of the project, two focus groups were invited to look at the picture in Figure 2 again. It is beyond the scope of this article to include these two dialogues in their entirety, but the excerpts and discussion below exemplify how a smaller group can facilitate a higher [end of page 52] degree of participation and more extended contributions. Table 5 shows that Group A’s dialogue was longer than Group B’s (a-b).

Table 5. The Dialogues of Two Focus Groups about the House Picture in Figure 2

An analysis of the turn-taking pattern shows that one of the reasons for Group A’s longer dialogue is that the discussion was more student-centred (as shown in c-d). Furthermore, it contained more dialogic features and more ideas. Nonetheless, students from both groups were seen to move from a literal to a metaphorical understanding of the pictures, and the dialogue in Table 6 shows how the researcher/teacher’s open question facilitated this process:

Table 6. Excerpt from Focus Group B’s Dialogue about the House in Figure 2

In Group A, a student expanded this metaphor by stating that the house is like a body, where the attic is one’s head, and that is where one’s dreams are.

Both groups managed to synthesize information and construct new knowledge about how growing up under a totalitarian regime might lead to idealization of other cultures and dreams of escape. In this case, knowledge construction took place without explicitly challenging one another’s ideas. The salient features contributing to intercultural learning in these dialogues are agency, a participative ethos and identification with the dialogue itself (Alexander, 2008; Vrikki et al., 2019; Wegerif, 2011). [end of page 53]

In Group A, the students offered alternative interpretations and added to each other’s points. Their curiosity about Czech culture was shown through their multiple questions about the picture. However, rather than waiting for my response, they answered each other’s questions. Hence, they showed agency (Alexander, 2008, p. 28) and created knowledge of another culture (Byram, 1997, p. 51; Deardorff, 2006, p. 254), such as through their discussion of informers and the dream of escaping to the West. As in the ‘bike with wings’ dialogue, S1 was willing to change his mind, this time without being explicitly challenged but seemingly after having considered the multiple interpretations offered by the group. The dialogic space where students ventured ideas appeared to make it safe to reconsider one’s initial interpretation and offer a new one, through comparing and evaluating the contributions (Vrikki et al., 2019).

In contrast, the turn-taking pattern of Group B’s dialogue was dominated by question-answer sequences, similar to the whole-group discussions in the classroom. It contained fewer dialogic features and was less student-centred. Analysing the forms of interaction, focusing on the teacher role, might illuminate why. Adopting the traditional role of a teacher, I explained and volunteered information, rather than asking the group for their opinions. This resulted in missed opportunities for student participation. Hence, posing open questions, withholding evaluative statements and allowing students to find the answers themselves are ways for the teacher to facilitate intercultural dialogues. On the other hand, careful transitions between teacher- and student-centred forms of interaction are important to build content knowledge (Vrikki et al., 2019). Despite the second dialogue being less student-centred, intercultural learning became manifest as the dialogic features become more prevalent. When the students took consecutive turns, built on each other’s ideas, and displayed agency, their curiosity about the other culture became visible.

Conclusion

The first research question asked what features of educational dialogues seem to be conducive to language students’ intercultural learning. The analyses of dialogues in this paper exemplify how dialogic features are employed in an ELT class. Through invitations that provoke thoughtful responses, the students are granted agency to contribute their ideas. These ideas, highlighting their curiosity, are extended, justified and constructively challenged, illustrating that facing conflicts might mediate intercultural learning. Facing [end of page 54] conflicting ideas, the students’ doxa are tested through questioning and justifying, leading to episteme. However, a participative ethos and identification with the dialogue are equally salient features, resulting in respectful exploration and reconsideration of initial ideas and a move from a literal to a metaphorical understanding of the picturebook narrative. This process entailed a co-ordination of ideas, which expanded the students’ thinking and led to co-construction of cultural knowledge.

The second research question asked how teachers might facilitate students’ intercultural dialogues. In alignment with Delanoy’s conception of dialogue as encompassing intercultural communication, I would argue that knowledge of dialogic features and how to mediate them is part of a teacher’s intercultural competence. This knowledge can help teachers transform conflicting encounters into intercultural learning experiences (Hoff, 2019, pp. 106-109). In this study, the students’ curiosity was aroused by their reading of a high-quality picturebook from another culture, and the open-ended activities facilitated intercultural learning. Furthermore, the small group setting of the focus group accommodated more extended contributions than the whole-group discussions of the classroom and provided an arena for dialogue. This is visible from measuring not only the length of the dialogues and the turn-taking patterns but also, more importantly, the evidence of dialogic features. Finally, in the two longest dialogues, the students themselves are the ones who drive these dialogues forward. The fact that the students are capable of assuming agency suggests that teachers should be careful of giving ‘correct’ answers before asking students for their opinions. Careful consideration of teacher- and student-centred forms of interaction allows students to contribute and share responsibility for the dialogue. The use of open questions is a starting point, but students may need practice seeking answers within the group rather than from the teacher.

Seasoned teachers know that giving up the front seat is not enough to make students conduct educational dialogues leading to intercultural learning. Many factors contribute, and some, such as the social dynamics of the group and student identity, are left unexplored in this article. The role of teaching materials – in this case, the picturebook – appears to play a role in prompting the students to talk and move beyond literal interpretations (Yeom, 2019).

A safe atmosphere, combined with knowledge of dialogic features, can contribute to a dialogic space where exploration of conflicting ideas can contribute to intercultural [end of page 55] learning. Teachers who grant autonomy to their students signal that students’ ideas are worthy of discussion and lead to learning. This can incite students to co-construct knowledge about other cultures and make classes more student-centred. Incorporating the dialogic features displayed in these intercultural dialogues in ELT may allow students to carry out dialogic talk in small groups autonomously. Finally, the study shows the potential of a high-quality picturebook to foster intercultural learning, when its pictures spark the students to move beyond literal interpretations and open up a dialogic space.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor, the reviewers and the journal editor whose thoughtful comments helped considerably in developing and clarifying my ideas, and finally Peter Sís for his support in the use of the images.

Bibliography

Sís, P. (2007). The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

References

Alexander, R. J. (2008). Essays on Pedagogy. London: Routledge.

Appleyard, J. A. (1991). Becoming a Reader: The Experience of Fiction from Childhood to Adulthood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bredella, L. (2000). Literary texts and intercultural understanding. In M. Byram (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopaedia of Language Teaching and Learning. London & New York: Routledge, pp. 382-386.

Bredella, L., & Delanoy, W. (Eds.). (1996). Challenges of Literary Texts in the Foreign Language Classroom. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., & Wagner, M. (2018). Making a difference: Language teaching for intercultural and international dialogue. Foreign Language Annals, 51(1), 140-151. doi:10.1111/flan.12319 [end of page 56]

Council of Europe. (2008). White paper on intercultural dialogue: “Living together as equals in dignity”. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/intercultural/source/white%20paper_final_revised_en.pdf

Council of Europe. (2018). Plurilingual and intercultural education: Definition and founding principles. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/platform-plurilingual-intercultural-language-education/the-founding-principles-of-plurilingual-and-intercultural-education

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative & Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10 (3), 241-266. doi:10.1177/1028315306287002

Deardorff, D. K. (2019). Manual for Developing Intercultural Competencies: Story Circles. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429244612

Delanoy, W. (2008). Dialogic communicative competence and language learning. In W. Delanoy & L. Volkmann (Eds.), Future Perspectives for English Language Teaching. Heidelberg: Winter, pp. 173-188.

DeWalt, K. M., & DeWalt, B. R. (2011). Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers (2nd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Dysthe, O. (2013). Dialog, samspill og læring: Flerstemmige læringsfellesskap i teori og praksis [Dialogue, interaction and learning: Plurivocal communities of learning in theory and practice]. In R. J. Krumsvik & R. Säljö (Eds.), Praktisk-pedagogisk utdanning: En antologi [Teacher Education: An Anthology]. Bergen: Fagbokforl.

Evans, J. (2013). From comics, graphic novels and picturebooks to fusion texts: a new kid on the block! Education 3-13, 41 (2), 233-213. doi:10.1080/03004279.2012.747788

Fenner, A.-B. (2001). Dialogic interaction with literary texts in the lower secondary classroom. In A.-B. Fenner (Ed.), Cultural Awareness and Language Awareness Based on Dialogic Interaction with Texts in Foreign Language Learning. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, pp. 13–42.

Hallberg, K. (1982). Litteraturvetenskapen och bilderboksforskningen [Literary Science and Picturebook Research]. Tidsskrift för litteraturvetenskap 3-4, 163-168. [end of page 57]

Hoff, H. E. (2014). A critical discussion of Byram’s model of intercultural communicative competence in the light of bildung theories. Intercultural Education, 25 (6), 508-517. doi:10.1080/14675986.2014.992112

Hoff, H. E. (2017). Fostering the “intercultural reader”? An empirical study of socio-cultural approaches to EFL literature. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1-22. doi:10.1080/00313831.2017.1402366

Hoff, H. E. (2019). Rethinking Approaches to Intercultural Competence and Literary Reading in the 21st Century English as a Foreign Language Classroom. Universitetet i Bergen, Bergen.

Jefferson, G. (1984). Transcription notation. In J. Maxwell & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Interaction. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. ix-xvi.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, Calif: Sage.

Littleton, K., & Mercer, N. (2013). Interthinking: Putting Talk to Work. London: Routledge.

Maine, F. (2013). How children talk together to make meaning from texts: A dialogic perspective on reading comprehension strategies. Literacy, 47 (3), 150-156. doi:10.1111/lit.12010

Matos, A. G. (2005). Literary texts: A passage to intercultural reading in foreign language education. Language and Intercultural Communication, 5 (1), 57-71. doi:10.1080/14708470508668883

Mercer, N., & Howe, C. (2012). Explaining the dialogic processes of teaching and learning: The value and potential of sociocultural theory. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1 (1), 12-21. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.03.001

Mourão, S. (2013). Response to the lost thing: Notes from a secondary classroom. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 1 (1), 81-105. Retrieved from http://clelejournal.org/response-to-the-the-lost-thing-notes-from-a-secondary-classroom/

Nikolajeva, M., & Scott, C. (2006). How Picturebooks Work. New York: Routledge. [end of page 58]

Pantaleo, S. (2007). Interthinking: Young children using language to think collectively during interactive read-alouds. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34 (6), 439-447. doi:10.1007/s10643-007-0154-y

Rojas-Drummond, S., Mazon, N., Fernandez, M., & Wegerif, R. (2006). Explicit reasoning, creativity and co-construction in primary school children’s collaborative activities. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 1 (2), 84-94. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2006.06.001

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. Deardoff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE, pp. 2-52.

Steen-Olsen, T. (2010). Refleksiv forskningsetikk – den kritiske ettertanken [Reflexive research ethics – the critical afterthought]. In G. Skeie, M. B. Postholm, & T. Lund (Eds.), Forskeren i møte med praksis : refleksivitet, etikk og kunnskapsutvikling [The Researcher in Collaboration with the Field of Practice. Reflexivity, Ethics and Knowledge Development]. Trondheim: Tapir akademisk forl., pp. 97-113.

Stephens, J. (2018). Picturebooks and ideology. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks. London: Routledge, pp. 137-145.

UNESCO. (2013). Intercultural dialogue. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/dialogue/intercultural-dialogue/

Vrikki, M., Wheatley, L., Howe, C., Hennessy, S., & Mercer, N. (2019). Dialogic practices in primary school classrooms. Language and Education, 33 (1), 1-19. doi:10.1080/09500782.2018.1509988

Wagner, M., Perugini, D. C., & Byram, M. (Eds.). (2018). Teaching Intercultural Competence Across the Age Range: From Theory to Practice. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Wegerif, R. (2008). Dialogic or dialectic? The significance of ontological assumptions in research on educational dialogue. British Educational Research Journal, 34 (3), 347-361. doi:10.1080/01411920701532228

Wegerif, R. (2011). Towards a dialogic theory of how children learn to think. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 6 (3), 179-190. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2011.08.002

Wegerif, R., & Mercer, N. (1997). A dialogical framework for investigating talk. In R. Wegerif & P. Scrimshaw (Eds.), Computers and Talk in the Primary Classroom. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 49-65. [end of page 59]

Wiseman, A. (2011). Interactive read alouds: Teachers and students constructing knowledge and literacy together. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38 (6), 431-438. doi:10.1007/s10643-010-0426-9

Yeom, E. Y. (2019). Disturbing the still water: Korean English language students’ visual journeys for global awareness. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 7 (1), 1-21. Retrieved from http://clelejournal.org/article-1-disturbing-still-water/ [end of page 60]