| Minority Cultures in Your School: A CLIL Approach

Margarida Morgado |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Picturebooks in ELT can be used to learn deeply and experientially about particular aspects of contemporary social living. The aim of this paper is to showcase how a particular picturebook may be utilized as the content in a CLIL approach to promote primary school children’s cognition about language learning and cultural identity, to promote communication through looking at and discussing pictures and to address cultures as identities and ways of thinking about the world. The picturebook My Two Blankets (2014), by Irena Kobald and Freya Blackwood, is used in a sequence of learning that highlights living between cultures as a common contemporary experience that all children should learn about and learn to accommodate. By drawing on the experience accumulated in several projects (IDPBC – Identity and Diversity in Picture Book Collections; the Visual Journeys project at the University of Glasgow and the C4C-CLIL for CHILDREN project), as well as on recent studies that link picturebooks to CLIL and bilingual practices, arguments are put forward and concrete examples are given on how to potentially enable all children, both minority and non-minority, to explore and negotiate cultural and linguistic identities, inclusion and diversity in deep and productive ways.

Keywords: picturebooks in CLIL; intercultural education; inclusion; minority cultures; My Two Blankets

Biodata:

Margarida Morgado (PhD) is a teacher educator in the areas of English, intercultural education and mediation as well as researcher in teacher education on the following topics: picturebooks, reading, intercultural issues, intercultural communication and mediation, and CLIL from primary to higher education. She is Coordinating Professor of Cultural Studies at Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco, Escola Superior de Educação, Portugal, and has been [end of page 28] involved in several Erasmus+ funded projects on reading promotion, foreign language teaching, and CLIL, the most relevant of which for this paper would be IDPBC – Identity and Diversity in Picture Book Collections (2015-2017) and CLIL for Children (2015-2018).

Introduction and Aim

Everyday reality is changing at a fast pace under the pressures of globalization and mass migrations. It often happens that primary classrooms are culturally diverse in the sense of a space in which children from many different cultural backgrounds, who speak different languages, coexist and interact. Rather than lament this diversity and worry about the expected learning difficulties of minority group children (such as Roma children, refugee children, or migrant children), this social and cultural diversity in classrooms can be harnessed by teachers to help all children learn about a fast-changing world and the implications this has for themselves and other children.

‘Funds of knowledge’, rich cultural and linguistic resources from home communities (Semingson, Pole & Tommerdahl, 2015), that children bring with them into the classroom can become ‘funds of identity’ through which they describe themselves (McGlip, 2014, pp. 33-34). Since it is through language that we learn about the world and communicate with it and about it, all the languages a child uses and learns are significant in defining their shifting multiple identities. Thus, it is important for teachers to acknowledge that all children bring these funds of knowledge to the classroom. It is also becoming more relevant that children be supported in their multilingualism through culturally relevant activities that might focus on, among other topics, why children speak several languages and why they are learning a second or foreign language. Children should also learn to value interacting in more than one language, for, although some children tend to use their multiple languages separately and in different physical spaces, it is important to encourage children to take advantage of their multiple language repertoires (Norton, 2013).

Despite its centrality for primary school curricula, minority and diverse cultures in schools is a complex social topic. This paper attempts to show how a picturebook can be used as content knowledge in foreign language education using a Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach to address this topic in productive ways with both minority and non-minority children through English. [end of page 29]

Of Visual Journeys, Diversity and Inclusion

An emergent trend in CLIL, through English, is to reappraise picturebooks and picturebook stories in the context of CLIL, referring to the linguistic, content, communicative and cognitive components of the primary curriculum (Ioannou-Georgiou & Ramírez Verdugo, 2011; Guadamillas Gómez, 2015). Ioannou-Georgiou and Ramírez Verdugo (2011) put the emphasis on the potential of the ‘stories’ in picturebooks to become cultural tools that facilitate access to language, essentially by rendering new language comprehensible and memorable. In their view, picturebooks also promote children’s interaction and communication and therefore promote fluency. Picturebook stories are culture in the sense that they represent cultural and intercultural values and may dictate verbal and non-verbal reactions from readers. Cognition is produced when child readers construct knowledge and meaning when looking or speaking about a picturebook, when they express feelings and ideas, but also when they realize how verbal language interacts with sounds and pictures. Stories involve searching for meaning and linking it to children’s prior knowledge, in a natural way.

As to content, for these authors, picturebooks offer curriculum-related vocabulary, they are not viewed as content per se. However, picturebook stories are presented as scaffolding resources in several ways: stories that can support children in their learning by being a familiar framework through which to convey a topic, a moral or an argument; through pictures they can support children who have difficulties with the verbal text; and lastly, given the endless uses picturebook stories can be put to, they may be used to address children’s favourite ways of learning (linguistic, visual, logical, kinesthetic, etc.) or learning approaches (interpersonal, learning with peers, problem-solving, etc.).

Guadamillas Gómez (2015), taking a different approach, argues that in the early stages of education, picturebooks are ‘authentic’ material through which to introduce cultural content and vocabulary in the classroom context, with the additional benefit that they extend learners’ vocabulary and add to motivation. By drawing on Sipe (1998), Lewis (2001) and Nikolajeva and Scott (2001), Guadamillas Gómez also highlights picturebooks as ‘multichannel realities’ that communicate more than one idea simultaneously (p. 113). Their use in classrooms as cultural resources can be employed for more activities than just reading or writing, such as analysing, understanding and communicating meaning through several modalities. [end of page 30]

Parallel to this educational trend, there is already a significant body of recent field-oriented research that supports the use of picturebooks to promote the inclusion and integration of children from minority groups, migrants and refugees. There are three ways in which to promote this inclusion: by bringing diverse reading materials into the classroom so that all children see themselves represented in them; by creating conditions for engagement with reading for all children through wordless picturebooks or visual literacy approaches; finally, by raising all children’s awareness to particular social, familial, and economic conditions that afflict minority, refugee and migrant children. The Visual Journeys (2005-2008) transcontinental project (Arizpe at al., 2014) led by Evelyn Arizpe, with Teresa Colomer and Carmen Martinez-Roldán, is a good example. The project addressed the use of wordless picturebooks with migrant children as a way into the culture and language of the host country. The study was based on developing bilingual strategies and respect for the language and cultural diversity of the children involved in the project.

As described by Pulverness (2014), through developing visual literacy, immigrant children or children from migrant backgrounds learn to make sense of their own experiences through their relation to the pictures they look at and talk about. By harnessing the potential of visual representations in wordless picturebooks, young immigrant children can be led to combine personal and mainstream representations of what they see in the culture they are living in (McGonigal & Arizpe, 2007). When immigrant children’s ‘readings’ are led towards their developing visual literacy and bilingualism, their integration and schooling is facilitated. One of the most interesting findings of the Visual Journeys project is the attention given to immigrant children in the classroom and how some of the children combined what they looked at in Shaun Tan’s The Arrival with their personal experiences and perceptions of migration (Arizpe et al., 2014). The other interesting aspect is the choice of the picturebook by Shaun Tan, a remarkable wordless postmodern picturebook, that proved to be ‘an attractive stimulus for talking’ because the visual displays in the picturebook pages demanded from children an interpretation (by actively participating in meaning construction), and also because the visual representations resonated with the children’s experiences (Arizpe, n/d). According to the project partners in Scotland, there were significant developments in the migrant children’s vocabulary and use of language, as the wordless nature of the picturebooks reduced the children’s fear of not understanding the English language (Arizpe, n/d). [end of page 31]

In an open invitation to teachers to create picturebook collections for their diverse classroom, the Erasmus+ EU-funded IDPBC (Identity and Diversity in Picture Book Collections) project (2015-2017, http://www.diversitytales.com/en/) further explored this approach by suggesting how to select, explore and use a particular collection of international picturebooks and visual narratives to enable primary school children to potentially negotiate issues of identity, inclusion and diversity in deep and productive ways.

Figure 1: IDPBC Annotated Bibliographic Catalogue

Like the projects that preceded it, IDPBC capitalizes on the educational affordances of powerful visual narratives to focus on issues of diversity, how children can learn to form their own identities or find their very particular place in the global world, how they learn to negotiate and mediate difference, and understand global mobility, poverty, displacement and social belonging (IDPBC, 2017, pp. 6-7). In this sense the project and the collection address the needs of all children and not exclusively those newly arrived or minority children. The picturebook collection put together by the IDPBC project used picturebooks to build an ethos of ‘acceptance’ and participation, promote children’s and human rights, assist children to resist demagogy and become critical readers, help them understand contemporary journeys (migration and mobility), foster their own understanding of the world and entitle all children to representation (migrants, refugees and minorities).

My Two Blankets: The Picturebook Story

My Two Blankets was chosen to illustrate a CLIL approach through picturebooks because it possesses a remarkable ‘cross-cultural potential of narrative imagery’ (Tan, 2015, p. xiv) and may be used effectively to promote interaction between children’s languages, English and their [end of page 32] L1(s), by drawing explicitly on their ‘reservoirs of linguistic and pragmatic resources’ in all the languages they know and speak (Ibrahim, 2014, p. 49).

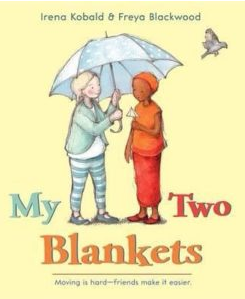

My Two Blankets (‘Moving is hard – friends make it easier’) (Kobald & Blackwood, 2014) tells the story of an immigrant girl, Cartwheel, who is newly arrived in a ‘strange’ Western-like culture. The book uses simple sentences and suggestive pictures, with a specific use of colour – warm yellows and reds for one culture and pale blue, white, pink and rose for the other. ‘She arrives in a strange country with strange people, strange food, strange animals and birds and even a strange wind’ (Mourão, 2018, p.72). The picturebook highlights linguistic barriers, ‘a waterfall of strange sounds’ (Kobald & Blackwood, 2014, unpaginated), acceptance of a new cultural identity, and integration, and features how language is at the basis of all intercultural encounters, as well as the process of learning a new language-culture through the appropriation of lexical items.

There are two young girls depicted on the picturebook pages: one dressed in red and yellow, and the other in pale blue and yellow. There are three intercultural encounters between them until they become friends and these are marked by the exchange of some concepts shown in pictures and words that visually cross the space above their heads. Thus, the waterfall of strange, ugly, threatening sounds becomes an exchange, an arch between them of symbols or pictures, words and sounds.

Figure 2: Cover, My Two Blankets, by Irena Kobold and Freya Blackwood, published by Little Hare Publishers

The blanket metaphor represents the ‘at home’ feeling of the protagonist, her own private space of refuge and escape, but also a space where she learns about reality – concepts and the language that goes with it. At first, she can only find comfort in her own blanket [end of page 33] decorated with the objects and living beings that are part of her cultural and linguistic repertoire. Then, through the successive intercultural encounters, she receives new words, concepts and realities and starts creating a new blanket, in colours and angles that are different from her own initial blanket, representing what she has learnt in the new culture. As aptly described by Mourão (2018, p. 72) ‘Her old blanket is an orangey red, showing the symbols from her home, its curves cradle her in their warmth. Her new blanket is angular, pale blues and greens, but gradually its angles envelop her as the new symbols fill the thematically divided sections, “And now, no matter which blanket I use, I will always be me”’.

Not every object represented in the red-and-yellow blanket will be recognizable to children who do not come from Cartwheel’s culture, while those objects in the blue-white-pink-cream blanket are probably more obvious and immediately recognizable as everyday objects and therefore nameable. This is also an interesting feature of the picturebook that teachers should foreground when facilitating children’s interactions with what they are looking at, as every child will be put in the position of the newcomer to a culture who does not understand what the objects are or what they are called. This will make it very obvious to the children that when you learn a new language you are learning to see new things and you are gaining access to (a) new culture(s). Furthermore, you are ‘unfettered by the constraints of recognition’, you really need to look at things and use your imagination to figure them out and make sense of them. You need to ask questions and make connections (Tan, 2015, pp. xiv-xv).

Thus, children can be led to understand that moving to live in another culture requires inference about things before you can name them, or ‘filling in the gaps of indeterminacy’ (Pulverness, 2014, p. 79). Children will have to speculate and find words and meanings for what they are looking at on the red-and-yellow blanket, unpacking the images by assimilating them to what they already know, a pluriliterate multilingual strategy.

Words and lexical items are a way into a new language, be it for a migrant child or any child learning a new language, so this picturebook presents an opportunity for children to test what they already know and enlarge their ‘blanket’ into a bilingual one with new words. Multiple heterogeneous cultural identities are dynamically being built by children through the various cultural (and linguistic) codes they may learn and use. This will be true for migrant children, but also for every child that contacts individuals from another culture, learns a new language-culture or is invited to explore the meaning of pictures. As Tan (2015, p. xiv) so [end of page 34] adroitly states, this may be an opportunity for child readers to depend on their own observation and experiential resources to make meaning.

My Two Blankets in the CLIL Classroom

My Two Blankets can become a quality learning material in the sense proposed by Mehisto (2012, p. 16): materials that sustain relational links between intended learning, the students’ own lives, the community and the integrated primary curriculum, by focusing on their own learning and use of English to understand about cultural diversity.

Intended learning

My Two Blankets is about the linguistic impact of moving to another culture for a migrant child. This experience can be compared to the children’s own experiences as foreign language learners or speakers of several languages. Through the blanket metaphor it represents, at an appropriate age level for child readers, how we perceive a foreign language (as strange) and then how it becomes part of us. It also shows language and culture to be interconnected through symbols and pictures.

Our most powerful argument in terms of the intended learning through a CLIL approach is that this particular picturebook can render visible two concepts for children: the first is what it means to learn a new language-culture in a new country (experiences of migration, mobility, refugees); the second is how they are learning about reality in and through an additional language (English) and through interpretation of what they see in the picturebook. Rather than using an additional language in a ‘natural way’, we are proposing that they reflect explicitly on learning a language and connect language to culture.

The visual narrative of this picturebook can probably sustain more interest and provide deeper opportunities for exploration than the written text, as children can explore its multiple layers (the ways in which words are represented as little objects that fly from mouth to mouth; as sounds of words can represent waterfalls; as words can be picked up and pasted into a blanket, etc.). In order for this to happen readers should be encouraged to interact inquisitively and in an open manner with what they see in the picturebook, with what they tell others about the picturebook, and with their own inner processes of meaning making.

Through these processes, children may start developing deeper conceptual understandings of what language learning entails, such as linking words in a new language to [end of page 35] concepts they already know. They may also start making connections between languages and cultural identities, albeit intuitively and tentatively, such as how a sound can create an emotion. Deeper learning often involves shared learning and peer interaction in more than one language, as well as a successful ability to communicate across languages and cultures (Meyer, 2015, pp. 2-3). At their age appropriate level, learners will be expected to extract information from texts in all relevant modes (Meyer, 2015, p. 5) and to communicate their understanding in a wide variety of subject specific modes, such as pictures, gestures and words.

Children’s Learning

Content and cognition. The topic ‘Minority Cultures in Your School’ when approached through this focus on language-culture has to be recognized as challenging content for primary classrooms. In this way we look at content as building up conceptual and perceptual cognitive processes rather than as something to be acquired and memorized (Unkelbach, 2006, p. 339 quoted in Mehisto, 2012, p. 20).

It may also be considered challenging content for CLIL in the sense that CLIL has traditionally been focused on the academic or scientific discourse of subject areas such as science or mathematics that several authors consider more precise (Mehisto, 2012, p. 18). However, the social discourse of this particular picturebook is as precise as any other in the way it offers verbal and visual representations of the following situations: initiating rapport with a person who speaks a different language; building your own repertoire of new words in a new language; treating newcomers with respect; children as active responsible citizens in welcoming other children, and building inclusion through play and talk.

Communication. When exploring the picturebook, children should be allowed to come up with their own meanings about language learning and how it affects the ways in which they look at reality. Personal and peer interactions about the pictures reduce the fear of making mistakes and in pairs and groups children may feel at ease to respond to a story event or pictures by using and comparing their own experiential resources. Cooperation with others contributes to making children feel safer to express an opinion, gives them the opportunity to learn at their own pace and to choose what is meaningful for them.

It is also important to allow children time and space to strengthen the connections between their personal conceptualizations in relation to what they are looking at, for [end of page 36] interpreting specific social and cultural contexts is always experience-dependent. Communicating those meanings to their peers may not be easy, so multimodality should be encouraged. Children can be invited to interact with others about what they see through verbal talk, pictures or graphic organizers. Furthermore, through discussion, telling, reading and exploring – a critical reading pedagogy – the picturebook can open up the creation of (imaginary) social situations of interaction, communication, collaborative thinking, and problem-solving.

Activities and assignments can use the language and content of picturebooks for authentic purposes, such as reducing the isolation of newcomers, integrating the experiences of migrant children in the classroom, analysing how one sees the world and finding words to describe it, or identifying how the children’s cultures and languages describe the world. By making cultural connections children will build their own knowledge about cultural and linguistic diversity.

Culture. When done through child communities of inquiry, picturebook explorations easily cover the four Cs of CLIL (Coyle, 2008; Coyle et al., 2010), namely Content, Communication, Culture and Cognition, thus expanding the understanding of integrating content and language acquisition to creating learning situations that are cognitively challenging for learners, while also developing the (inter)cultural dimension or dynamic cultural constructs (such as learning a new or additional language, spatial relations, familial organizations, notions of time, etc.) that shape learners’ identities.

Minority, migrant or refugee children can learn, through looking at the pictures and talking about them with other children, how to actively negotiate their changing identities and reconstruct meanings for their experiences of displacement (Guerrero & Tinkler, 2010). However, this is not enough as an inclusive strategy if we do not also facilitate mainstream children’s access to the experiences of other children, thus promoting their empathy through reading picturebooks, by putting themselves in the place of the other and voicing an opinion and feelings about their experiences.

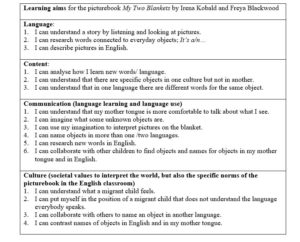

Learning aims. Mehisto (2012, p. 17) claims that in a CLIL-specific manner, learning intentions should be shared with students in appropriate ways by breaking down language, content, communication and cognition learning intentions into short and long-term outcomes that are both realistic and challenging. Table 1 describes an example of learning aims for a [end of page 37] sequence of learning based on My Two Blankets to be shared with children in the upper levels of primary school in the framework of the topic we have been discussing. These ‘can do’ statements are learner-centered, guided outcomes expected from the children’s interactions with the picturebook and relate to what children think they have learnt in the process of looking, talking about and exchanging views with other children. The statements are expressed in a language children can relate to and enable them to reflect on their learning as a set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills. They are not supposed to be a form of assessment, but essentially a strategy to engage children in reflecting on their learning. However, as reported for activities related to ‘can do’ checklists in the European Language Portfolio (ELP), these statements may eventually have a ‘positive effect on learner motivation’ (Goodier, nd., p. 7).

Table 1. Learning aims for a sequence of learning on My Two Blankets [end of page 38]

The Role of Teachers

As picturebook mediators, teachers should start by pointing things out and helping readers/listeners notice details in the pictures, as well as offer to make connections between one picture frame and the next (Arizpe, 2013, p. 22). Perry Nodelman has pointed out that it is important to develop among children ‘an attitude of respect for the communicative powers of visual codes of signification’ (1988, p. 191) and to enable this, some authors (Arizpe et al., 2015, p. 202) suggest that it is useful to start with an ‘introductory walkthrough’ as a warm-up activity where the teacher introduces the picturebook, its front and back covers, endpapers, title page and dust jacket and so forth. This will be useful to introduce some vocabulary for later use by the child readers or give children examples of the metalanguage they will need to speak about what they look at. In addition, one reading or showing may not be enough for child readers to get the intended meaning of a picture in relation to a story line. There has to be time to go back and forth between the pages. Or there might be a page by page presentation and moments for collaborative exploration of pictures with peers.

As teachers, it is important also to decide on the focus: If a teacher wishes to focus on open-ended questions for children to interpret the pictures, asking ‘What do you see?’ or ‘What do you think it is?’ or ‘What makes you think that?’ might be a good starting point. If the teacher’s concern is for children to approach the picturebook as a problem-solving activity to be addressed collaboratively with peers, it is important that children be allowed to follow their own inquiries and questions. Note that this strategy would be particularly suited to newcomers to the class, as it would give them the possibility to find their place in the classroom and in society through a community of inquiry (Arizpe et al., 2015, p. 196).

Bilingual studies with picturebooks may be useful to consider when planning for classroom language and sequence of activities. Suggestions drawn from Hu and Commeyras (2008, pp. 11-12; 28) include:

- Pre-teaching key vocabulary (critical for understanding of the text) through a variety of activities, and in thematic sets, as facilitated by the picturebook blankets;

- Finding words for pictures when they have already been named: What is this? It is…;

- Contrasting names for objects in two or more languages: How do you say… in English? By using objects represented in the blanket; [end of page 39]

- Making sentences about picture frames after reading the picturebook to elicit the children’s story telling: What is happening to …? Does she ….?.

Visual literacy through picturebooks may perhaps be best developed through diagrams and mind maps or graphic strips. Arizpe et al. (2015, pp. 204-5) suggest inviting children in pairs or groups to annotate copies of the picturebook pages. The two blankets in the picturebook, for example, can be pasted onto paper and children may write the name of objects in the languages they know. These annotated blankets of new words in English may be revisited whenever the children wish. Using parts of the picturebook double spreads for children to annotate and add words in English may also help them to learn to look more attentively at pictures and thus develop visual literacy skills, such as analysis of colour, line, perspective, while using their new foreign language to annotate pictures.

Creative uses of the picturebook may involve children taking photos for their own ‘bilingual blanket’, of things they cherish and can name, thus originating their very own language-culture learning portfolio. If the classroom is linguistically diverse, this kind of activity may raise interest for each other’s languages and cultures and create opportunities for plurilingual explorations based on visual displays.

One last point concerns classroom organization. The interaction of learners in pairs and groups is a powerful strategy to construct meanings for what they see in the pictures with the language(s) they already possess. Pair and group work will offer children the opportunity to revisit the sections of the picturebook that interest them most and to share their interests, questions and responses in a ‘safe way’ (Kurkjian and Kara-Soteriou, 2013, p. 9). Group interaction will probably carry meanings away from the text as it will connect children’s experiences to what they are looking at; it will probably also unveil their implicit assumptions, and this should be allowed to happen as a classroom dynamic that brings together reading and child experiences.

Resources

There are already many resources to support using My Two Blankets, which are available online (Open Educational Resources) and that any teacher can adapt to a CLIL lesson in several contexts. For a quick reference, the Reading Australia website at https://readingaustralia.com.au/lesson/my-two-blankets/ offers the following suggestions: [end of page 40]

- Work with the blanket metaphor by asking children to wrap themselves in a blanket and tell others how they feel: do they feel safe and happy like Cartwheel? Why/not? They could also write a sentence in the languages they know about: I feel safe/happy when….

- A worksheet on ‘My Security Blanket’ (ALEA, 2015) for children to fill in with their words or with the words they can identify of (positive or negative) feelings on several pages of the picturebook (happy, sad, excited, nervous, pleased, frightened or worried). However, this activity loses the distinctions between the two different blankets depicted in the picturebook (one curved, the other angular; red and orange colours against blues and whites, etc.) and thus should be complemented with closer looks at Cartwheel’s blankets and invite children’s creativity to imagine the shape, colour, and feel of their own language blankets.

Conclusion

It is important to call the attention of teachers to intercultural themes and how they can be arrived at through reading picturebooks, by giving examples of several projects where picturebooks have been used to promote an awareness of intercultural communication or representation. It is never easy to identify single picturebooks that meet the criteria of all teachers or entirely match a curriculum. A suggestion has been made that My Two Blankets might be brought into a foreign language classroom using a CLIL approach, by guiding children to reflect on learning a new language (both as a migrant and as a learner of any foreign language) and to think about what it feels like to belong to a minority culture as a migrant recently arrived in a new country. My Two Blankets, when seen as content, addresses a highly relevant topic/theme, given that in increasingly diverse communities, a sense of belonging and acceptance of others who are different or come from different minority backgrounds is valuable learning both for newcomers and for the host children. My Two Blankets was chosen not only because it might help children understand what it feels like to be ‘forced’ to learn a new language in school as a migrant or refugee, but also because it may facilitate children making meaning of what learning a foreign language entails in terms of new sounds, new words and new identities.

The pedagogic activities suggested are meant to increase children’s awareness of literacy strategies based on the visual, the interplay of the visual and the verbal, as well as the [end of page 41] aesthetic object that is the picturebook, while simultaneously contributing to language and cultural awareness raising: to learn English, to learn about learning English, to learn about empathy – heightening learners’ sensitivity to migrant children’s experiences in school, to learn about migration and its linguistic consequences.

The foregrounded argument of the article is that picturebooks can become cultural tools, when appropriately chosen and used, and can be used to mediate meanings of content topics. By focusing on a brief analysis of some features of My Two Blankets it has been suggested that picturebooks can be explored in more depth in order to:

- Identify important cross-cultural issues

- Locate different positions on those issues

- Evaluate how important the information in the picturebook may be for the learners

- Communicate learners’ own meanings about those issues to others.

This has been exemplified in the context of understanding multiple linguistic identities not only among minority children but in every child who is learning a foreign language.

Acknowledgements

IDPBC (Project Number: 2015-1-LT01-KA201-013492) and C4C (Project number: 2015-1-IT02-KA201-015017) are EU-funded projects.

Bibliography

Kobald, I. & Blackwood, F. (2014). My Two Blankets. Chicago, IL.: Little Hare.

References

ALEA (2015). Task for My Two Blankets.Retrieved from: https://static-readingaustralia-com-au.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2015/11/My-Two-Blankets-My-Blanket-Worksheet.pdf

Arizpe, E. (n/d). Visual Journeys. Glasgow: UKLA.Retrieved from: https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_234337_en.pdf

Arizpe, E. (n/d). Visual journeys with immigrant readers: Minority voices create words for wordless picturebooks. Retrieved from: http://www.ibbycompostela2010.org/descarregas/11/11_IBBY2010_19.pdf [end of page 42]

Arizpe, E. (2013). Meaning-making from wordless (or nearly wordless picturebooks: what educational research expects and what readers have to say. Cambridge Journal of Education 43 (2), 163-176.

Arizpe, E., Bagelman, C., Devlin, A. M., Farrell & M. McAdam, J. E. (2014). Visualizing intercultural literacy: Engaging critically with diversity and migration in the classroom through an image-based approach. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14 (3), 304-321.

Arizpe, E., Colomer, T. and Martínez-Roldán, C. (Eds.). (2015). Visual Journeys through Wordless Narratives. An International Inquiry with Immigrant Children and ‘The Arrival’. London: Bloomsbury.

CLIL for Children-C4C (2018). Teacher’s Guide on CLIL Methodology in Primary Schools. Florence: CLIL for Children. Retrieved from: http://www.clil4children.eu/

Coyle, D. (2008). CLIL – a pedagogical approach. In N. Van Deusen-Scholl, & N. Hornberger, Encyclopedia of Language and Education, (2nd ed.). Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 97-111.

Coyle, D., Hood P. and Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ghiso, M. P. & McGuire, C.E. (2007). “I talk them through it”: Teacher mediation of picturebooks with sparse verbal text during whole‐class readalouds. Literacy Research and Instruction, 46 (4), 341-361.

Goodier, T. (nd.). Working with CEFR can-do statements. An investigation of UK English language teacher beliefs and published materials. (Unpublished Master’s diss.). British Council: British Council ELT Master’s Dissertation Awards: Winner. https://englishagenda.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/filefield_paths/working_with_cefr_can-do_statements_v2_1.pdf

Guadamillas Gómez, M. V. (2015). Elmer: a classroom intervention for intercultural bilingual education. Odisea, 16, 111-125.

Hu, R. & Commeyras, M. (2008). A case study: Emergent illiteracy in English and Chinese of a 5-year-old Chinese child with wordless picture books. Reading Psychology, 29 (1), 1-30.

Ibrahim, N. (2014). Perceptions of identity in trilingual 5-year-old twins in diverse pre-primary educational contexts. In S. Mourão and M. Lourenço (Eds.), Early Years Second Language Education: International Perspectives on Theories and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 46-61. [end of page 43]

IDPBC (2017). IDPBC Annotated Bibliographic Catalogue. Retrieved from: http://www.diversitytales.com/flipbooks/bookcollection/files/assets/basic-htm

Ioannou-Georgiou, S. & Ramírez Verdugo, M. D. (2011). Stories as a tool for teaching and learning in CLIL. In S. Ioannou-Georgiou & P. Pavlou (Eds.), Guidelines for CLIL Implementation in Primary and Pre-primary Education. Nicosia: PROCLIL, pp. 137-55. Retrieved from: http://arbeitsplattform.bildung.hessen.de/fach/bilingual/Magazin/mat_aufsaetze/clilimplementation.pdf

Kurkjian, C. and Kara-Soteriou, J. (2013). Insights into negotiating Shaun Tan’s The Arrival using a literature cyberlesson. SANE Journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education, 1 (3), 1-15. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sane/vol1/iss3/2

Lewis, D. (2001). Reading Contemporary Picturebooks: Picturing Text. London: Routledge Falmer.

McGlip, E. (2014). From picturebook to multilingual collage: Bringing learners’ first language and culture into the pre-school classroom. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 2 (2), 31-49.

Meyer, O., with Halbach, A. and Coyle, D. (2015). A Pluriliteracies Approach to Teaching for Learning. Putting A Pluriliteracies Approach into Practice. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Mourão, S. (2018). Kobald, Irena and Blackwood, Freya (2014). My Two Blankets. (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 6 (1). http://clelejournal.org/recommended-reads-6/

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C. (2001). How Picturebooks Work. New York: Garland.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and Language Learning: Extending the Conversation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Pavlenko, A. and Blackledge, A. (Eds.) (2004) Negotiation of Identities in Multilingual Contexts. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Pulverness, A. (2014). Evelyn Arizpe, Teresa Colomer and Carmen Martinez-Roldán. Visual Journeys through Wordless Narratives: An International Enquiry with Immigrant Children and ‘The Arrival’. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 2 (2), 76-80.

Semingson, P., Pole, K. and Tommerdahl, J. (2015). Using bilingual books to enhance literacy around the world. European Scientific Journal, 3, ISSN: 1857–7431. Retrieved from: [end of page 44] https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/download/5216/5014

Sipe, R. (1998). How picture books work: A semiotically framed theory of text-picture relationships. Children’s Literature in Education 29 (2), 97-108.

Tan, S. (2015) Foreword. In Arizpe, E., Colomer, T. and Martínez-Roldán, C. (Eds.), Visual Journeys through Wordless Narratives. An International Inquiry with Immigrant Children and ‘The Arrival’. London: Bloomsbury. [end of page 45]