| ‘Where am I in the text?’ Standing with Refugees in Graphic Narratives

Jena Habegger-Conti |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This article aims to contribute to current research on the use of graphic narratives and picturebooks for intercultural education with young adult learners in English Language Teaching. Using the concept of positioning from a critical visual literacy approach, three graphic narratives about refugees are analysed for places in which the reader is invited to enter the text and stand with refugees: When Stars are Scattered (2020) by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed; Illegal (2018) by Eoin Colfer, Andrew Donkin and Giovanni Rigano; and The Arrival (2006) by Shaun Tan. The analyses offer practical classroom tools for instigating ethical encounters, including some questions for classroom discussion aimed at helping pupils recognize the interconnectedness of all humans. The article also shows how refugee graphic narratives can dismantle the us/them binaries of some intercultural education approaches.

Keywords: graphic narrative; refugees; intercultural education; positioning; critical visual literacy

Jena Habegger-Conti (PhD) is Associate Professor of English literature, culture and didactics at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences in Bergen, Norway. Her recent publications include ‘Not Reading the Signs in Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina’, in J. Habegger-Conti & L. Johannessen (eds) Aesthetic Apprehensions: Silences and Absences in False Familiarities (Lexington, 2021) and ‘Reading the Invisible in Marjane Satrapi’s Embroideries’, in A. Grønstad & Ø. Vågnes (eds) Invisibility in Visual and Material Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Introduction

The opportunities for using picturebooks and graphic narratives to promote intercultural competences in English language teaching (ELT) in a European context are well-documented in research. Lydia Sindland and Anna Birketveit (2020) have demonstrated that picturebooks may help young readers learn to decentre while gaining perspectives about others, and Sissil Lea Heggernes (2019) found potential for classroom dialogue on a graphic memoir to facilitate pupils’ intercultural learning in specific areas like exploring conflict. Anne Dolan (2014) has suggested that picturebooks about refugees offer opportunities for exploring complex power structures with young learners in a form that is accessible to them. Gail Ellis (2018) demonstrates the potential of visual texts for developing cultural literacy, and thereby intercultural competences, by helping pupils to concretely see the differences and similarities between their world and the world of another.

The recent proliferation of graphic narratives about refugees, in particular those addressed to young adult readers such as Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed’s When Stars are Scattered (2020), and Eoin Colfer, Andrew Donkin and Rigano’s Illegal (2018) adds another dimension to the use of graphic narratives in intercultural education in ELT. Refugee narratives produced after the refugee crisis in Europe, which began around 2014, highlight a messier intercultural reality than the one envisioned by many of the compare-and-contrast type competence aims related to the study of other cultures in intercultural education. Refugee narratives and migrant literature may in fact shine a necessary light on some of the limitations of intercultural education, namely that it tends to view concepts like culture, nation and identity as stable and unified (Dervin, 2016), while also upholding an our-culture / their-culture binary (Dervin, 2016; Holliday, 2011). For example, even the reflective practice of decentring is premised on an outside / inside, centre / periphery system. By nature of their national and cultural liminality, migrants and refugees emphasize the ‘inter’ of intercultural, and the fluidity of culture and identity. By nature of their journeys, migrants and refugees also dismantle the over there / over here divide, as teachers and pupils around the world negotiate new multicultural realities in their classrooms.

Another feature of migrant and refugee narratives regarding intercultural education is that instead of highlighting different ways of living around the world, the stories generally aim to provide readers with a better understanding of migrants and refugees while emphasizing the interconnectedness and vulnerability of all humans. For example, the final sentence in the epilogue to Illegal is ‘And every person is a human being’, and a poem read at the end of When Stars are Scattered uses the millions of stars in the night sky as a metaphor for the interweaving of human stories.

Migrant and refugee graphic narratives are thus particularly well suited to enable what philosopher Judith Butler (2012) has referred to as an ethical encounter. In ‘Precarious life, vulnerability, and the ethics of cohabitation’, Butler is curious about how the images of disasters and human life violations that fill the daily news implicate us in the lives of those who are far away, and about how, and under what conditions ethical responsibility arises. In short: Why do we care about what happens to someone we do not know, who lives far away from us? Butler concludes that to see ourselves as sharing in the lives of others on the planet we must embrace an ethics of cohabitation that depends upon the ‘reversibility of proximity and distance’ (2012, p. 137): ‘that what happens there also happens here’ (p. 150). The images of war and other disasters that have departed from one place to become a shared reality on screens around the world testify to the interconnectedness of all humans. According to Butler, to recognize this sharing of the world is a necessary condition for the ethical encounter to occur. In the framework of intercultural education, this means being able to see those who live in faraway places as part of a ‘we’ rather than a ‘them’.

This article seeks to pursue further the notion of ethical encounters in intercultural education through refugee graphic narratives. The analyses that follow will offer practical classroom tools for instigating ethical encounters, as well as for shifting the focus of intercultural education from learning about others to standing with others. Three graphic narratives for young adult readers will serve as examples: When Stars are Scattered (2020) by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed; Illegal (2018) by Eoin Colfer, Andrew Donkin and Giovanni Rigano; and The Arrival (2006) by Shaun Tan.

When Stars are Scattered (2020) is illustrated by Victoria Jamieson, a Newbery Honor Winning Graphic Novelist for children, and written by a former Somalian refugee, Omar Mohamed. It has already received a good amount of praise from critics, including The New York Times Book Review, and it was a finalist for the American National Book Awards 2020 for Young People’s Literature. When Stars are Scattered tells the true story of its author, Omar Mohamed, who arrived at the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya at the age of four with his brother Hassan. We learn how Omar and Hassan, who are parentless as a result of war, spend their entire childhood in the camp until, at the age of seventeen, Omar receives an offer for resettlement from the United States. Today Omar continues to work with refugees and the end of the book provides readers with more information about his current projects, as well as photos of his family.

When Stars are Scattered is one of the few graphic narratives about refugees in which the entire story takes place in a refugee camp. Readers see first-hand what daily life is like in a refugee camp from the mundane hour-long wait to get clean water, to the frustrations of attending the camp school where the teachers only speak English, to the widespread irritation at the end of the month when the food supply has run out at the camp. The book also shows the detriments to mental health from being forced to live year after year outside of time and without a future.

Colfer, Donkin and Rigano’s Illegal (2018) is another story of two orphaned refugee brothers, also narrated as a personal testimony by a young boy, Ebo. The story takes readers along the incredibly dangerous journey that many migrants make from Niger to Agadez, across the Sahara to Tripoli, and onward by boat to Italy. Although the characters in Illegal are fictional, the epilogue claims that ‘every separate element of it is true’. The book aims at underlining the common humanity of both the reader and the refugee, while problematizing the word ‘illegal’. Illegal received the 2019 Excellence in Graphic Literature Award for Young Adult Fiction.

Shaun Tan’s The Arrival (2006) has won numerous awards and is unquestionably the most known and the most written about of the three books to be analysed here. The Arrival is an entirely wordless picturebook which was published well before the 2014 European refugee crisis, but because the story takes place in an unknown time and unknown land, it can be interpreted as an historical tale of migration, or as a present-day narrative about refugees. In the book the main character must flee his home country due to an unspecified threat, depicted as a giant dragon lurking in the village. The book follows the migrant’s long journey by ship, and focuses on the daily struggles that he experiences in learning a new language, learning new cultural systems, and trying to make a wholly foreign place feel like home.

An ELT Approach to Standing with Others in Refugee Graphic Narratives

A popular concept in children’s literature research is that books can act as windows to see into another world and into lives and experiences that are not their own, and as mirrors through which they can see themselves (Dolan, 2014, p. 92; Bland, 2015, p. 28; Bishop, 1990). However, African American scholar Rudine Sims Bishop (1990) claimed that windows can also be barriers: they may allow readers to remain removed, even shielded from what is going on just outside the window. To counter this, Bishop offers the idea of a sliding glass door to signify that books can also allow readers to walk into another world (1990, p. ix), and have a ‘lived experience’ in that other world (2012, p. 9).

Bringing together Bishop’s sliding door concept with Butler’s concept of cohabitation to analyse graphic narratives in ELT may help readers to see and reflect on their position in the world and the interconnectedness of people. Looking for places where images invite readers to stand with characters, and reflecting on the act of standing with others as an essential position for responsiveness to injustices, may in turn help to bridge fictional – classroom – real world divisions. In the following I will show how the concept of positioning, used in a critical visual literacy approach, can help teachers identify places of potential ethical encounters in graphic narratives and picturebooks.

Critical Literacy and Positioning

To analyse a text for its position we must first accept that no text is neutral. Every text-maker makes decisions in creating a text that are the result of his or her beliefs, values, attitudes, social positions, and even geographic / or spatial location on the planet. Likewise, no reader is neutral: every reader approaches a text from a particular position. Whether or not we accept the position on offer by the text is up to each reader. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘ideal reader position’, in contrast to the ‘resistant reader position’. An understanding of how a text is positioned and seeks to position its readers can empower readers to understand that texts have social effects in the real world. This approach is different from popular strategies in intercultural education that seek to develop pupils’ emotional, empathic or cultural competences.

The concept of positioning is central to a critical literacy approach that aligns well with the competency aims for intercultural education and democratic culture, emphasizing real world action over classroom learning. Briefly summarized, a critical visual literacy approach seeks to: disrupt the commonplace, interrogate multiple viewpoints, focus on sociopolitical issues, and take informed action (Lewison, Flint & van Sluys, 2002). When applied specifically to the teaching of literary texts, including graphic narratives and picturebooks, the approach could be modified to: disrupting the ideal reader position, rejecting a single version of a story and ensuring that other voices are heard, interrogating positions of privilege in the text, and highlighting the real-world relevance of the text and inspiring action. The last of these aims, which views learners as actors and not just spectators in the world, is a central goal of the critical pedagogy approach developed by Brazilian educator Paolo Freire in the 1960s. This goal is reflected in the Council of Europe’s Reference Framework for Competences for Democratic Culture, which emphasizes civic engagement, dialogue and respect (2018, p. 25). Critical literacy is thus a highly relevant approach for English language teaching in a European context.

Critical visual literacy combines the analytical language of visual semiotics (Serafini, 2013; Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2006; Janks, 2014) with the tenets of critical literacy to determine how images position their readers to accept particular representations of the world (Janks, 2014). One of the central tools in a critical visual literacy approach is to understand how images work to position readers: the choice of camera angle, frame, or lighting, for example, or the choice of colour or layout all have real-world effects on how we read and comprehend the message communicated. Imagined social interactions and social relations also play a role in text-maker choices and how images position viewers (Kress & Van Leeuwen 2006, p. 115). For example, an image of a group of people photographed from a distant angle posits an imagined relationship with the viewer that is also distant from the depicted subject, which may in turn affect the reader’s capacity for empathy.

A Focus on Positioning

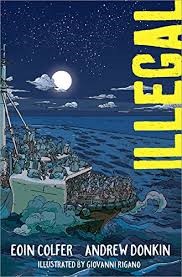

If we consider the social relationship depicted between reader and refugee that the cover of Colfer, Donkin and Rigano’s Illegal (Figure 1) presents, we see that we are positioned from far away, and from a high angle, looking down on the refugees. We are positioned from an angle by which we see only the backs of most of the refugees. The dark blue colours of night further obscure their faces and forms. The fact that we do not see anyone’s face means that the image may not actively encourage an emotional response to the suffering depicted. The choices that the illustrator has made on this cover position readers to see the refugees more as a mass of bodies rather than as individuals, and they do not seem to be a part of the reader’s world.

To help pupils gain a basic understanding of positioning from a critical visual literacy perspective, and whether they want to accept or resist the position on offer, teachers can begin with a lesson showing how a single image can be analysed, pointing out the type of shot (the distance from the subject, for example: close-up or long shot), the angle of the shot (high, low, eye-level), the framing (whether the image has a frame or whether it appears endless), the type of line or drawing style (thick or thin lines; more realistic, impressionistic or cartoony), and body position or body language of the subjects depicted (Appendix). Pupils can then be encouraged to reflect on the effect these choices have. Two resources for teachers who wish to learn more about how visual narratives communicate are Hilary Janks et al. (2014) Doing critical literacy, and the open access guide, Visual literacy in English language teaching (Goldstein, 2016).

After familiarizing pupils with ways that text-maker choices can affect how they perceive an image, the following questions may be used to analyse the covers of graphic narratives or picturebooks about refugees (Appendix):

- What are some of the choices that the illustrator has made to depict the refugees on the cover of this book (hint: how would you describe the shot, angle, colours, framing, illustration style, body language, etc.)?

- How do these choices position us to see the refugees?

- What other ways could refugees be depicted on the cover of this book?

- Choose one image from the book for the cover. Explain how your choice of image changes the way that readers are positioned to view refugees.

Figure 1. Cover of Illegal. (Eoin Colfer & Andrew Donkin, illus. Giovanni Rigano, 2018).

A Focus on Visual Direct Address

Understanding positioning may also help readers to recognize and reflect on where they stand on real world issues related to refugees and migrants. For example, Shaun Tan’s The Arrival does not position readers to make eye contact with the main character until he has arrived at the immigration office. Prior to this point we are positioned to watch him on his journey from a distance, as though looking through a window, or camera lens. In the immigration office we see the man sitting in front of us. He is depicted from the waist up, facing us, as though sitting in a chair directly across from us. Asking pupils, ‘Where are you in this office?’ may surprise readers who have not previously considered where they are in a text. The image positions readers to sit in the role of the immigration officer, in the role of someone who has the power to accept or deny this man’s request. We might indeed feel sorry for him. His struggle with the language is clearly depicted through a series of nervous gestures: he looks down, scratches his head, and fiddles with his hat. However, if we focus away from how the text makes us feel to how the text has positioned us, we must accept that The Arrival places the reader in a position of power, as the one who can accept or reject the migrant’s request. Further questions in the classroom could bring out critical literacy’s social justice aims: ‘How might this position mirror your real-world position?’ and ‘In what situations do you have the power to decide when people are in or out of your group?’

In Negotiating critical literacies with teachers, Vasquez et al. point out that when pupils understand their own involvement in a text, they are more likely to see the role they play in real-world transformations. They write: ‘Even though we may be committed to social change, more often than not, we are part of the dominant culture and hence, part of the problem. Until we understand how our current identity and the positions we take mitigate our reform efforts, we cannot truly become part of the solution’ (2013, p. 18). Thus, looking for ‘sliding door’ moments in a text in which we see ourselves as a part of the world of the story can be a key element of a social justice approach to reading.

There are other times in The Arrival when the images position the reader to stand in the place of the migrant, such as when his new friends offer him the gift of a small pot. The friends look out from the image, directly at the reader, and seem to hand the pot to us. Helping pupils to find places of visual direct address in a text, when a character looks directly out at the reader, draws attention to places in the text where the reader is invited to have a personal connection with the subject depicted. This disruption of the reader’s / viewer’s gaze is a disruption of power binaries between the reader and the represented subject, a practice I have termed ‘seeing eye to I’ (Habegger-Conti, 2019, p. 157). The instance in which a character looks out from the page and ‘sees’ me, provides an opportunity for me to rethink who I am – and possibly also where I am – in relationship to the other. Questions such as ‘Why do you think Shaun Tan has chosen to position us in the place of the migrant here?’ and ‘What effect does this choice have?’ can help readers to move beyond simplified readings for empathy or identification with refugees to reflect on more complex issues like us / them divisions (Appendix). Questions about positioning can be modified for younger readers, or readers with lower-level language skills: ‘Where are you standing in this picture?’ ‘What would you do / say in this scene?’ By allowing readers to experience both being in the position of power, and in the position of needing help, The Arrival refuses readings that posit the refugee as other.

A Focus on Framing Devices

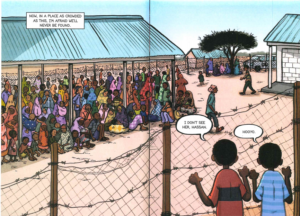

Paying attention to the framing devices used in graphic narratives offers yet another possibility for analysing the reader’s position in relation to the story told (Appendix). One of the more striking features of When Stars are Scattered is its use of, and discarding or breaking of, the comics panel. The first page is a powerful example. Unlike many refugee stories which begin with the war or disaster that led to fleeing the home country, or with the arduous journey to freedom, When Stars are Scattered opens with an unframed, double-page spread showing a scene from inside the camp itself (Figure 2). The composition of the image is at first confusing: a large group of people sit behind a fence, while the reader stands behind Omar and his brother Hassan on the other side of the fence. Because we have been conditioned by the onslaught of news images of refugees in camps to see the people behind the camp fences as separate and other than us, our first interpretation of this scene may lead us to believe that Hassan and Omar are standing outside the camp with us, looking in. However, the written text and following pages inform us that we are inside the refugee camp, alongside Omar and his brother.

The double-spread is also unframed, which gives the additional effect of blending the space of the fictional world with the real world (it seems that the scene extends out to the space of the reader’s hands). Rather than seeing Omar and Hassan’s life in the camp through a window, the absence of a frame around the image acts as a sliding door, positioning the reader as someone hearing the story from the inside. (This first scene marks a stark contrast to the position in which the reader stands in relation to the cover and opening scene in Illegal.)

Figure 2. When Stars are Scattered, first opening (Jamieson & Mohamed, 2020, pp. 4-5).

Used with permission from Penguin Random House, New York.

While the framed border does return for the majority of the narrative in When Stars are Scattered, the instances in which it disappears or is broken are worth noting. Often the images of the camp are unframed, positioning the reader to see that the tents and huts go on forever in all directions; it appears there is no other world beyond the refugee camp for Omar and Hassan. On page 197, the arms of one of Omar’s friends are drawn reaching out of the panel, towards the reader. In another unframed double-page spread, the reader is positioned as standing behind Omar and his friends, looking out on the camp through their eyes. Near the end of the book, Omar receives an envelope of papers which will either offer or deny resettlement to the United States. The reader watches through four panels as Omar opens the envelope, but the actual document informing him that he has indeed been selected for resettlement is drawn outside of these panels (Figure 3). The image is drawn so that the readers may place their hands on the document alongside Omar’s hands. Here we are positioned not only to stand with Omar, but to stand as Omar, looking down at the document from the angle of his eyes.

Figure 3. Omar’s resettlement notification (Jamieson & Mohamed, 2020, p. 150).

Used with permission from Penguin Random House, New York.

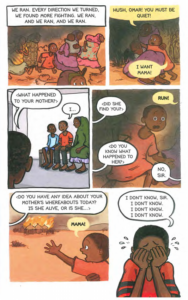

Another example of how framing may be used to position readers occurs when Omar must explain to a United Nations worker what happened on the day he was forced to flee. In his retelling, the dark borders of the individual panels disappear, but the gutters remain, inviting an intimacy with readers, while at the same time creating a sense of fragmentation and gaps (Figure 4). Readers are positioned to enter the unframed scene, but the lack of a panel frame also allows the illustrated event to bleed into the white space of the gutter, fragmenting the story and highlighting the moments of trauma that we cannot see, the moments in which we are shut out from seeing. Omar’s sharing of the story comes to an abrupt stop when he remembers his mother. In the last panel of the page, he is depicted in a white space that reaches beyond the borders of the other images, to the right and bottom edges of the page. When asked if he knows where his mother is today, and whether she is alive or not, Omar stands, seemingly alone against a white background, disconnected from the rest of the story. Drawing pupils’ attention to Omar’s position in this scene highlights the interconnectedness that the text invites with the reader: as he cries, Omar has moved from the framed panel of the story to the outer, unframed space of the page held by the reader. To maximize opportunities for interconnectedness, pupils may be asked to find other images in the text in which they felt particularly connected to Omar, or can see themselves as a part of his world (Appendix). They can then be asked to explain the text-maker choices that they feel enabled this connection. Asking pupils to use the terminology of critical visual literacy will help them practice the language of visual analysis. Pupils will also hopefully become more attuned to text-maker choices in the images that surround them in their everyday lives, developing stronger visual literacy skills.

Figure 4. Omar retells what happened on the day he fled his home (Jamieson & Mohamed, 2020, p. 183).

Used with permission from Penguin Random House, New York.

In conclusion, to read When Stars are Scattered for places in which we are invited to enter into the narrative, as though through a sliding glass door, offers the potential for an ethical response to the refugee crisis because it aims to reverse the problem of proximity and distance that Butler addresses with her ethics of cohabitation. Graphic narratives and picturebooks that help readers to more clearly see themselves in other, perhaps faraway places, reverse what we think of as ‘here’ and ‘there’ and may lead to enriched discussions of human rights and social justice. Readings that incorporate an understanding of the concept of positioning may also help pupils achieve aims in intercultural education that emphasize the relational and fluid sense of ‘inter’ over a static and sometimes overly generalized knowledge of cultural similarities and differences. As Butler argues, whether or not we are inclined to respond to suffering witnessed from a distance depends very much on our recognition of all humans as co-inhabitants of the same planet. Visual texts that position the reader as standing with others can play a key role in helping pupils to recognize that we are all vulnerable, which, according to Butler (2012, p. 145), is the impetus for ‘seek(ing) to make all lives livable’.

Bibliography

Jamieson, Victoria & Mohamed, Omar (2020). When Stars are Scattered. Dial Graphic.

Tan, Shaun (2007). The Arrival. Hodder Children’s Books.

Colfer, Eoin & Donkin, Andrew, illus. Giovanni Rigano (2018). Illegal. Hodder Children’s Books.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix-xi.

Bishop, R. S. (2012). Reflections on the development of African American children’s literature. Journal of Children’s Literature, 38(2), 5-13.

Bland, J. (2015). Pictures, images, and deep reading. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 3(2), 24-36.

Butler, J. (2012). Precarious life, vulnerability, and the ethics of cohabitation. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 26(2), 134-151.

Goldstein, B. (2016). Visual literacy in English language teaching: Part of the Cambridge Papers in ELT series. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/us/files/7015/7488/7845/CambridgePapersInELT_VisualLiteracy_2016_ONLINE.pdf

Council of Europe (2018). Reference framework of competences for democratic culture: Context, concepts and model (Vol. 1). Council of Europe Publishing.

Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education: A Theoretical and methodological toolbox. Palgrave.

Dolan, A. (2014). Intercultural education, picturebooks and refugees: Approaches for language teachers. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2(1), 92-109.

Ellis, G. (2018). The picturebook in elementary ELT: Multiple literacies with Bob Staake’s Bluebird. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8-18 year olds. Bloomsbury (pp. 83-104).

Habegger-Conti, J. (2019). Reading the invisible in Marjane Satrapi’s Embroideries. In A. Grønstad & Ø. Vågnes (Eds.), Invisibility in visual and material culture. Palgrave Macmillan (pp. 149-164).

Heggernes, S. L. (2019). Opening a dialogic space: Intercultural learning through picturebooks. Children’s Literature in English Language Education 7(2), 37-60.

Holliday, A. (2011). Intercultural communication and ideology. Sage.

Janks, H., Dixon, K., Ferreira, A, Granville, S., & Newfield, D. (2014). Doing critical literacy: Texts and activities for students and teachers. Routledge.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

Lewison, M, Flint, A. & van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382-392.

Serafini, F. (2013). Reading the visual. An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. Teachers College Press.

Sindland, L. & Birketveit, A. (2020). Development of intercultural competence among a class of 5th graders using a picturebook. Nordic Journal of Modern Language Methodology, 8(29), 113-139.

Vasquez, V. M, Tate, S. L., Harste, J. C. (2013). Negotiating critical literacies with teachers: Theoretical foundations and pedagogical resources for pre-service and in-service contexts. Routledge.

Appendix

Questions for instigating ethical encounters in the classroom with graphic narratives and picturebooks about refugees: