| ‘Pathetic Geek Stories’: A Practical Approach to Introducing a Challenging Graphic Narrative

Jessica Allen Hanssen |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Choosing a challenging text, applying a consistent critical approach to it, and creatively building up to a discussion of its themes as relevant to both itself as part of a literary tradition and as an extension of the ideas of difficulty and vulnerability, can enable student teachers to feel empowered and included in an interpretive community. This can in turn lead to considered discussions of identity and belonging, and productive literary analysis to follow. This article explores these ideas in the context of graduate-level English teacher education coursework on the graphic memoir Fun Home by Alison Bechdel (2007) and examines the theoretical basis for this work. It includes exemplars of an in-class activity, using a critical-creative approach, and also provides discussion of how elements of this activity can be adapted when working with graphic novels with other target groups. In doing so, the article explores the potential of multimodal reading strategies for identity- and community-building in the profession of teaching.

Keywords: graphic novels, Alison Bechdel, teacher education, interpretative community, reflection

Jessica Allen Hanssen is a Professor and the Faculty Coordinator for the Bachelor of English degree at Nord University, Norway. Her areas of interest are American literature, especially nineteenth- and early twentieth-century fiction, short-story theory, narratology and young adult fiction. Her education research focuses on the intersection of critical theory and English education for middle grades, and the early introduction of critical reading, especially reader-response and narratology-based teaching strategies.

Introduction

With increased interest in and widespread acceptance of the graphic novel as a vital tool in the English teacher’s literary repertoire (Goldstein, 2016; Habegger-Conti, 2021), it can become an equally powerful tool for teacher educators in their attempt to reinforce identity-building in their student teachers’ professional development. The study and production of multimodal narratives can support the building of communities, not just interpretative communities for a given text (Fish, 1982), but the professional community of those entering the teaching profession. When Fish famously wrote that ‘it is interpretative communities, rather than either the text or the reader, that produce meanings’ in Is there a text in this class? (p. 2), the interpretative community he imagined to form had perhaps little, if anything, to do with teacher identity, or how a teacher guides learners towards community formation itself, which, for me, is very much at the heart of the teaching profession.

Steig (1989) comes closer to addressing the teaching profession with his notion of inter-subjective meaning-making in the secondary classroom, as Reichl (2009) calls attention to (p. 241). As central to classroom literary discussions, Steig (1989) highlights the concept of, not ‘knowledge’ or even ‘interpretation,’ but ‘understanding’ (xiii), which connotes community in a way that interpretation does not. Steig’s literary exemplars, however relevant to secondary English studies they might be, do not engage multimodal texts as we understand them today. Teacher educators, in their search for a challenging and relevant literary text which encourages identity-building among future teachers, might find what they need in a graphic novel. The graphic novel, like other multimodal materials, has specific affordances that help with such community building, as well as certain challenges for the teacher educator to consider. This article therefore reflects, from both theoretical and practical perspectives, on how this challenging format can connect learning about narrativity with community building in the context of English teacher education.

Context

In response to an increasing collective awareness that English student teachers should be capable of reflecting on their chosen profession and engage disciplinary difficulty in a safe and accessible way, my colleagues and I developed a masters-level teacher education course called Critical Reflections on Literature and Language in English Teaching Practices at a Norwegian university. This course provides a broadened reflection on English language, literature, genre, and cultures, and invites learners to develop in-depth knowledge on the strength of questioning ideas and collecting support from various experiences. Identity-building, which is central to language learning, comes as part of such processes, and building a strong interpretative community is therefore central to my approach to the course.

My module in the course examines how the challenging graphic narrative provides space for personal reflection, literary artistry, and social critique. For a discussion of the function of time in narrative, Ricoeur’s (1980) article ‘Narrative time’ provides an approachable theoretical framework. While Ricoeur’s work on time and narrative stretches out over several volumes, this article encapsulates some of his main ideas in a more readily accessible way, stressing the paradox of what he later refers to as the ‘fictive experience of time’ (Ricoeur, 1985, p. 6). On the one hand, our time-based ways of inhabiting the written world remain imaginary to the extent that they exist only in and through the text. It is all in our heads, or on the page – narrative time is not real. But on the other hand, since we learn to understand our own experience of time when we read about what happened to someone else, reading about time allows for the text to confront the world of the reader: narrative time is real, as much as any time can be.

I use the graphic memoir Fun Home (2007) by Alison Bechdel as a common basis for coursework and an in-class activity. Teachers who have worked with graphic novels in their classrooms tend to value graphic narratives as an economic and entertaining storytelling medium, one that uses the affordances of multimodality to connect text with relevant experiences. Eisenmann and Summer (2020) have noted that ‘nowadays they are an integral part of ELT’ (p. 59), so it is perhaps consistent that student teachers should gain some experience working with them. Multimodal texts, such as graphic novels and other graphic narratives, are here situated as part of a longer narrative tradition, representing both a creative and thematically economic way to meet their curriculum aims for English, which emphasize criticality, cross-curricular work, and multimodality and, as a result, invite response in kind. Fun Home represents a challenging graphic novel for this environment in two ways: It deals with complex personal and social issues from an LGBTQ+ perspective, and it presents them in a complex visual and referential way that pushes against linear boundaries of time.

As a middle grades English teacher educator in Norway, I was looking to explore the versatility of the graphic medium to challenge my student teachers’ conceptions of what themes or maturity levels a graphic narrative could explore, but also aimed at achieving an emotional response and encouraging a discussion of difficulty (whether skill-based, thematic, or social) as part of the more general question of what it means to be a confident literature teacher. ‘Challenging’ here is ‘understood in multiple ways according to the different contexts and ages of the reader. […] It is never the text alone that is in focus but how we deal with the opportunities for challenge in the classroom community’ (Bland, 2018, p. 2).

In order to empower learners as part of such a community, they need to experience meaningful discussions and productive literary analysis. This is enabled by a consistent critical approach to the graphic novel and a creative building up to a discussion of its themes, which are relevant both as part of a literary tradition and as an extension of the more general ideas of difficulty and vulnerability. In the middle grades teacher education context, such challenging themes, which may tap into different ideologies and belief systems, need a particularly safe learning environment. A clearly challenging text such as Fun Home, which deals with LGBTQ+ identity and questions views of home and family, could be difficult for even graduate-level learners, and might engage them in a great deal more than a language lesson. Discussions of how, for example, gender, ability, and adolescent anxiety inform our self-awareness and our responses to the world around us can be encouraged at graduate level by foregrounding these issues in the context of a student teacher’s professional development. Reading and working through a challenging text such as Fun Home together allows for community building and makes such discussions easier to enter into.

As part of the module’s focus on multimodality and meaning making, I developed a group pre-reading activity that fuses personal narrative with experimental and creative visual storytelling, as a way into Fun Home that could potentially be transferred to other classroom contexts. The activity asks student teachers to collaboratively write and illustrate a mildly embarrassing incident from adolescence, using specific software, and then to share with the others. This collaborative storytelling activity teaches student teachers about the value of time and distance in narrative (Ricoeur, 1980), an abstract literary concept that has practical value when applied to the classroom context, as can be seen in the discussion section below. The activity centres the future English teacher as someone who, once they have encountered their own adolescent difficulties, can help younger language learners do the same. Symbolic storytelling such as this engages language learners on many levels, not least the aesthetic and affective. The next section will develop and reflect on the theoretical background for the activity in more detail, before contextualizing Fun Home itself and connecting theory to practice through presentation of the activity.

Aesthetic and Affective Aspects of Storytelling

We can perhaps understand aesthetic learning as a ‘process where the student learns through participation and creation to rework, reflect, and communicate about themselves and the world’ (Hanssen & Jensvoll, 2020, p. 285), thus bridging narrative and community formation through the creative act. This definition is based in part on Lutnæs (2018), who developed a model that defines five creative habits and serves as a lens to examine dimensions of creativity in teachers’ assessment rubrics from 27 schools across Norway. It identifies possible steps towards cultivating responsible creativity in design education, and the model is readily applicable to various English Language Teaching (ELT) contexts worldwide. Creativity can be developed through ‘aesthetic learning processes understood as learning the subject content through participating and creating, and where the individual may express herself and her understanding through language, drawings, text and bodily activities’ (Brekke, 2016, p. 9). According to Austring and Sørensen (2006), aesthetic learning processes can also be described as ‘a way of learning where the student translates her own impressions of the world through aesthetic mediation creating aesthetic expressions of form, and through this is able to reflect on and communicate about herself and the world’ (p. 107).

What arises from such processes is the kind of critical-creative process which Pope (1995) identifies as central to a ‘de- and re-centring’ of the literary text (p. xiv).While Pope does not present working with graphic novels as a specific example of the critical-creative process, it is clear that the idea would bear even more fruit with the inherent multimodality of the format. In a language learning context, the process of critical inquiry, that is the employment of elements of critical theory, which de- and re-centre, mirrors the creativity indicators that are used in arts classes: processes that are inquisitive, disciplined, imaginative, collaborative, and persistent (Lutnæs, 2018). English teachers must learn to stand uncertainty and tolerate ambiguity, to ask questions about given truths, and be prepared to solve problems creatively in known and unknown situations.

Another recent critical framework that has attracted attention and influenced my understanding of how to build a community with care is affect theory. Sara Ahmed (2010) defines affect as ‘what sticks, or what sustains or preserves the connection between ideas, values, and objects’ (p. 29), and notes that ‘to be affected by something is to evaluate that thing’ (p. 31). This idea of internalized interpretation has consequences for a teacher’s methods, since the teacher does not inherently know how students will respond to or evaluate any given artistic encounters. After all, one of the significant challenges a literature teacher faces, is that many texts are produced not to make the reader feel good but to make them think and to challenge their values. Understanding how a work of art, such as a literary text, resonates within an individual’s experiences or memories to produce a certain affect is the basis for all processes involved in teaching literature, from text selection to its presentation to the types of critical expression it is used to engender. When we choose to focus on feelings and values as part of an interpretative process, we create more memorable lessons, but this must be handled with care.

In my teaching context, and that which my student teachers will enter, English is more than a utility subject, it is also a formative subject (Biesta, 2014; The Norwegian Directorate of Education, 2019). My understanding of this distinction is informed by the need for teachers to build a welcoming, inclusive, and supportive learning community. This feeling of belonging forms the basis for the ELT classroom as a safe place for self-expression, regardless of whether one is an L1 or L2 user. In reader-response terms, we join a text’s interpretative community and participate on equal footing with other readers with opinions, experiences, or understandings that challenge our own. If we accept that English is ‘used as a lingua franca, i.e., a common, transnational language of communication, by a large number of people who do not have that language as their mother tongue’ (Hoff, 2018, p. 74), then we therefore carry with it our own cultural connotations as well as the hybrid forms that come with experience. Iversen (2012) calls for a ‘community of disagreement’ (p. 62), an idea which promotes the individual interpretation of text at the same time as engaging a diverse interpretative community who shares some, but not all, of the same context for critical reading, which activates the building of a strong and diverse interpretative community. One might extend this line of thinking to the needs of English student teachers as well, as they do not only need an interpretative community in the context of their university education, but need to know how to create one in their own future ELT classrooms.

An English teacher should feel comfortable choosing classroom texts or approaches to any given text, to which learners can bring their own criticality as part of a process of discovery and insight. The word ‘text’ itself challenges teachers to consider the subject’s contents against the meaning of English as a utility subject versus English as a formative subject, and to reflect on how to best encourage lifelong enjoyment of English. Many times, however, the written text is not as important to the learner’s development as the unwritten narratives of teachers themselves: what a teacher says about their own experience or challenges carries deep implicit learning value as well. Student teachers, who are learning how to lead a classroom after many years of being on the small-desk side of the room, need to have this idea made explicit in order to benefit from it in practice. While it is relatively easy to get, I suggest, middle grades English student teachers to understand how to explain grammar rules or technical vocabulary for interpreting literature, it is significantly more challenging to get them to open up to the idea of themselves as value-bearers. Yet this is what middle-grade students perhaps seek most of all: an empathetic voice of experience and reason against the noise of life and constant change. Student teachers must learn to relate to ‘within-time-ness’ (Ricoeur, 1980, p. 173), and to process their past experiences as part of an ongoing identity-building process. Working with Fun Home, a narrative of ‘within-time-ness,’ allows the teacher educator to explore this concept with them on practical, aesthetic, and conceptual levels.

Fun Home

The primary narrative we discussed in the module was Fun Home (2007) by Alison Bechdel, perhaps the most sophisticated graphic narrative I have ever encountered. In this memoir, which Bechdel subtitles as a ‘family tragicomic’ (thus herself blurring the line between fiction and memoir), she interweaves her own awareness of her emerging identity as lesbian with her complex relationship with her family history and especially with her father, who she discovers also grappled with his sexual identity. The story is unsparing: the introspection Bechdel provides both in words and image is brutal and raw. The colour scheme of Fun Home is appropriately lean, using exclusively blue/green tones outlined in black, as though Bechdel attempts to recollect and visualise vague dreams or memories. In her illustrations, she moves between a near-photographic, documentative style for depicting buildings, furniture, and artefacts, and a looser, more expressive style when it comes to illustrating herself and other people, which indicates the complexity of her home life and personal relationships. Bechdel draws on her father’s occupation as an English teacher (and part-time mortician) to connect her storytelling to other central narratives of cultural identity displacement such as the myth of Icarus, The Great Gatsby and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, among many others, and infuses it with feminist and psychoanalytic theories.

Fun Home deals with important American history that is often left out of history books – Bechdel addresses the Stonewall riots of 1969 and the various ways in which men and women alike were forced to hide or sublimate their desires in a reactionary post-WWII USA –but which is readily applicable to other cultural and national contexts. The AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, gay rights, gender non-conformity: These are elements of diversity that deserve exploration. Also, Fun Home considers the sexuality of both parents and children, a cultural taboo that does not often make it to the pages of a young adult novel and is connected to cross-curricular themes of public health and welfare. For these reasons, Fun Home, suffice it to say, is not a text for the English language learner per se, or students unfamiliar with the graphic format and its unique storytelling language. However, for experienced learners it delivers the same opportunity for discussions of difficulty and identity as a less complex narrative would in a less experienced language learning environment.

And did I mention that it is also funny? Even amid its saddest realizations, Bechdel’s sense of humour about the awkwardness of some of her experiences helps to lighten the mood and add further depth and nuance to her narrative. An early example, and one that is ultimately relatable for the book-loving ELT audience of a certain age, is when young Alison, yearning for validation of her feelings, narrates ‘[o]ne day it occurred to me that I could actually look up homosexuality in the card catalog’ (Bechdel, 2007, p. 75). My student teachers are old enough to remember the card catalogue system in their school libraries, and they took delight in the sheer nerdiness of Bechdel’s quest for knowledge. This sense of humour was something I wanted to carry into a relevant pre-reading activity for the novel, as it is my experience that adding a touch of humour to a lesson helps it become memorable.

Bechdel has made some important and innovative choices about how to work with time in Fun Home. She tells the story forwards and backwards, jumping back and forth in time and setting. Even the interstices – breaks in the narrative or the spaces between frames – function as part of the story because they invite us to imagine what happened during these spaces. Also, she repeats the same moment, that of finding out about her father’s death, several times, but each time it is altered somewhat by the new information that is now available, which adds complexity. This is also part of what it means to be a teacher – one has to say the same thing, several times, in several different ways, in order to reach everyone. Each approach one chooses to teaching a literary text is a doubling back on time, presenting a new version of the story or a fresh outlook on it. The teacher’s goal becomes for everyone to eventually take away something useful to them. According to Margaret Simon (2016), ‘Bechdel’s book offer(s) students and the instructor a map not only of her own becoming, but of the way becoming interacts with and resists opportunities for belonging’ (p. 143), which makes it an ideal text for challenging future English teachers to consider their role in the communities to which they belong and will belong.

Pathetic Geek Stories as a Classroom Activity

The following section describes how I applied elements of identity-building, aesthetic learning processes, and affect theory to creating and evaluating a pre-reading activity for Fun Home. After explaining my pedagogical reasoning for the activity, and describing the activity in full, I will present and analyse selected examples of finished student work to highlight significant visual elements of the comics the students created, and expand on this analysis with context that arose from in-class discussion as students presented their work.

Due to the focus on graphic narratives in my approach to narrative and time, with particular focus on Fun Home, I wanted to create an in-class activity that used the affordances of multimodal text to explore how our life experience can be narrativized in a way that creates a sense of safe distance. Additionally, I wanted to use digital resources in a logical way that could be directly transferable to a middle grades school environment, as this is a curricular aim that they will also have to meet.The format of the class, planned as digitally taught even before the pandemic, meant that we had the opportunity to use internet technology as it was intended, making geographical boundaries irrelevant for students working across multiple campuses. Despite the geographical distance, I wanted to ensure that they trusted me and each other enough to feel comfortable in complex discussions of a complex narrative that might well produce complex feelings.

The internet, for better or worse, brings people together. Perhaps one of the most immediate expressions of this togetherness is our collective delight in what my 13-year-old daughter might call ‘cringe’ – that familiar feeling of affective anxiety based on a situation that goes wrong in relatable but unique ways. One of my favourite sources of cringe humour is a long-running web comic called ‘Pathetic Geek Stories’ by Maria Schneider (2008). Schneider invites her readers to send in stories from their adolescence, which she then draws as kind but accurate comics. When one reads these brief comics and feels the pain of an event from each narrator’s teenage experience, one feels less alone. Inspired by this, my activity invites students to work together to share one of their own pathetic geek stories and make their own comic story, as an opportunity to narrativize their experience and to create a bridge to other literatures as part of an identity-building process.

Students were placed in groups of three. Since the course combines students on two campuses of the same university, I ensured that there were students from both campuses in each group, as well as gender balance. Each group member has a specific role to play to bring the activity to completion. One group member is the ‘Pathetic Geek’: there is no shame in this, because the whole point is that, in a way, we all feel like pathetic geeks at one time or another, and that is completely normal. The pathetic geek is asked to remember an embarrassing moment from their teen years. It does not have to be something life-changing or deeply personal: the smaller the better. They are asked to reflect on questions such as: How would you tell one of your middle school students about something awkward that happened to you back then? Which details would you keep, and which would you discard? They should expect questions from the other group members. The story in its entirety needs to fit into six frames, so they might imagine it as six sentences long.

Another group participant is asked to serve as the ‘Main Illustrator’. This role might be taken by the most tech-savvy of the group. The main illustrator is asked to use the website storyboardthat.com to tell the pathetic geek’s story in six frames. StoryboardThat (https://www.storyboardthat.com/) allows users to make six-frame comic strips for free, with longer comics requiring a paid pro account, but that is the only significant limitation. To my mind, this is not even as much a limitation as it is an opportunity to encourage and reinforce ideas on form and composition. Storyboardthat.com is intuitive and offers lots of choices for how to arrange text and images to tell a simple story in graphic form. Since it is both free and intuitive, it can be used by any ELT teacher with internet access. In this activity, the main illustrator is asked to lead a group discussion on how they should structure each frame, and use the elements of storyboardthat.com to tell the story. They should save their work and share it with the other group members to review. Once everyone in the group has seen it and offered advice, and they have made the desired changes, the main illustrator should post a link to the finished comic on the class’ online classroom.

The third group member serves as the ‘Explainer’, or storyteller. Their job is to present the comic to the class when resumed in plenum. They should read the comic out loud and with a dramatic flair. They should describe the creative process their group used, and how their group made the decisions that led to the finished product. They should also attempt to make a statement on how this particular pathetic geek story is really universal to all of us. Finally, the explainer should attempt to describe a potential connection from this real-life story to another, fictional, story that they have encountered before – either in or out of school: how does what happens to another literary character speak to the experience described in their group’s comic?

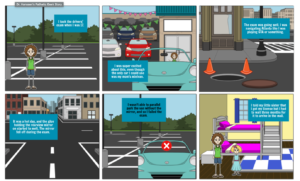

In order to fully establish the idea for the students, and in pursuit of the ‘exemplary learning environment’ (Wagenschein, 1965/2008), it was essential to offer something of my own pathetic geek experience as an example – I, as the teacher in this environment, must demonstrate my own willingness to be open and vulnerable and to engage risk, if I am to expect students to do the same, and also to provide a practical example of what a finished product might look like. So, I reached into my soul and found an example of a place and time in my youth when I felt very much like a pathetic geek: my first attempt to get a driver’s licence, as illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Teacher illustration

Even in the six simple frames of Figure 1, I was able to incorporate several key nuances of multimodal storytelling, such as the text colour shift in frame five to indicate a crisis point in the plot, and also the size contrast when I was in the car, or between myself and my younger sister, whom I lied to in shame for having failed the test. All told, the example comic took me about 30 minutes to produce on storyboardthat.com – I could have used much more time and made it even more detailed, but that was not the point. I was working alone, and collaboration takes significantly longer, which I wanted to account for by not producing an unrealistic example.

Students were given two hours to complete the task, and then we met again as a large group for the storytelling and discussion. This part of the class produced many of the affective ‘cringe’ moments I was hoping for, and served the purpose of creating a closer community, but also opened up for genuinely important discussions of how gender, ability, and adolescent anxiety inform our self-awareness and our responses to the world around us, and how these change over time. I have asked the students for their permission to share their stories, and there are no identifying markers in the illustrations.

Following the presentation and analysis of their work, I will remark on how this activity works on a theoretical and aesthetic level, and how it functions as an effective way into working with a challenging graphic text such as Fun Home.

Figure 2: Student Illustration 1

It is interesting to notice the way the illustrator of Figure 2 has made the girl crush larger than the main character, which denotes both pubescent reality as well as his feelings of unrequited love. Frames four and five (the bus) indicate motion that is not otherwise narrated, and the jagged word balloon indicates the girl’s anger. During the discussion, the ‘Pathetic Geek’ informed the rest of the class that he was in fact only 12, not 16 when this happened, but that he was worried about being the only boy who liked girls at that age, and chose to age it up because he thought it would be funnier. He found out from other male students that he was not alone with his feelings as a 12-year-old, and this reassured him, even as an adult.

Figure 3: Student Illustration 2

It is noticeable that the setting of Figure 3, a train, is relatively static, and how the other passengers are rendered pale, as though invisible. This is in contrast to the main character, who is more colourful and emotive – this indicates that she felt more visible or conspicuous than the other passengers, although they probably barely noticed her because they were worried about themselves. Notice as well how the illustrator indicated the mode of sound through both music notes and a sound balloon. Sound is important to the story in more than one way. The ‘Pathetic Geek’, who is in fact severely hearing impaired and uses interpreters in class, noted that she was embarrassed at the time about her disability and thought this incident would signal her difference to the cool-seeming strangers on the train. In discussion, the class assured her that to them she was just another passenger, and that a moment of extra noise is nothing out of the ordinary on a train.

Figure 4: Student Illustration 3

Here, in Figure 4, the multiple settings of school and the mall represent the lifeworld of the teenager, and the 70/30 split shows, not tells, which of these is most important in the main character’s life at the time. Having a crush on a teacher in a subject you enjoy happens very frequently, but for the ‘Pathetic Geek’, the moment when she encountered the math teacher outside of his natural habitat disturbed her lifeworld. It is highly unlikely that from that distance he noticed a small piece of chewing gum stuck to her hand, or thought anything of it if he did, but in the narrative, it further signals something being out of place. The last slide darkens the setting and removes everything else, leaving the main character alone with her feelings. In the discussion, it was revealed that most of us had entertained major crushes on a teacher at one point or another (usually an English teacher, I might add!), which made her feel a lot better.

Discussion

Going back to introducing the idea of the interplay of time and narrative, which was a significant goal of my overall module, I could see clear parallels in the students’ work and the discussion with the theoretical essay by Paul Ricoeur (1980), which they had previously read. These are fairly complex ideas, but they are relevant when we think more about how graphic novels work. Bordelle (2015) calls attention to the ways in which ‘modalities such as images and sound work together with text in a way that strengthens overall impact’ (p. 92). Graphic novels also allow for arranging and rearrangement of their material in a non-linear way; we read them the way we want to. Finally, graphic novels teach flow and time. When we decide how long a ‘thunk’ sound takes when we see a sound balloon with ‘thunk’ written inside, or which frame to linger on the longest, we have asserted our right to determine the order and logic of our own universe. We have agency over how we interpret the information, and that is an empowering and liberating experience.

This same idea also informs how the students understood their own experience as filtered through time. When the embarrassing thing happened, it was ‘the end of the world,’ as one student put it, and the exercise brought those feelings to the surface; but with time and experience, and through the additional distance of relating the story for someone else to tell, students came to understand that it was ultimately no big deal in the grand scheme of things. This is important to consider when school students encounter their own stumbling blocks, whether academic or social – teachers should not be too quick to dismiss the moment because they know it gets better, but relate with empathy to the learner who is living the moment now, and gently acknowledge their feelings. This builds an important trust relationship for if and when students hit larger, more serious stumbling blocks.

This activity not only achieved my goal of getting the class to reflect on the various challenges they have overcome, but it also prepared them to be more observant of their own agency as they read Fun Home and watched an author interview for our next meeting. Because I had done the work to build an interpretative community and to scaffold the literature, when the discussion turned to analysing Bechdel’s complex narrative of encountering family secrets at the same time as she awakened to her own homosexuality, the students felt free to say more, and on more conceptually difficult themes, than I suspect they would have with a more traditional text and teaching method.

I began the discussion by asking some fairly standard questions about Fun Home’s format and structure, such as:

- How does the chapter organization of Fun Home work? Is the story told sequentially? Why does Bechdel move forwards and backwards in time? What purpose does that have?

- How would you describe the font of Fun Home? How do elements of the text such as the font Bechdel uses influence its meaning?

(Additional discussion questions can be found in the Appendix.)

These questions helped us rapidly segue into the more challenging conceptual questions that Fun Home raises, such as:

- What is a perfect family? The one you have, or the one you want? Is there any such thing?

- How do you feel about openly discussing sexuality at school? What are some advantages and disadvantages to sexuality as an ELT theme?

- Where do you think Bechdel blurs the lines between herself as a character and herself as an author? Are there any ethical boundaries to this?

(Additional discussion questions can be found in the Appendix.)

As the discussion progressed, I encouraged both cross-discussion among students and also direct connection to Fun Home via textual examples, but otherwise only contributed when asked what I thought. I did not want my ideas to be centred, but to be an amanuensis in its traditional usage as the discussion’s assistant or guide. My line of questioning moved from general and utilitarian examination of the text to being more focused on identity formation, both as individuals and as student teachers, before broadening still wider to issues of democracy and representation. The pathetic geek story activity both foregrounded and informed the discussion throughout.

Conclusion

My engagement with Fun Home in the teacher education context enabled the versatility of the graphic medium to challenge my student teachers’ conceptions of what themes or maturity levels a graphic novel could explore. It also served the equally important purpose of achieving an affective, emotional response and enabling discussion of embracing difficulty and ambiguity as part of a larger discussion of being a confident literature teacher. Considering the pre-reading activity as an aesthetic learning process, it was plain that the activity related to the aims of my working definition of this as ‘a learning process where the student learns through participation and creation to rework, reflect, and communicate about themselves and the world’ (Hanssen & Jensvoll, 2020). It was rewarding to see the core areas of inquisition, discipline, imagination, collaboration, and persistence (Lutnæs, 2018) made real to the students as they used the graphic medium themselves to relate and contextualize their own experiences. Through collaborative and visual storytelling, they were able to briefly exist both inside and outside of time, Ricoeur’s ‘within-time-ness’. Since we had already revealed and processed some of our own adolescent anxieties in the pre-reading activity, moving back to talking about those of a fictionalized character seemed easier by comparison. Further, since students had used time and energy in a creative act, they felt capable of reflecting on Bechdel’s artistic choices. Finally, because the activity generated a sense of community, students felt safe when it was time to reflect on their emerging identity as English teachers, and they knew they were among friends who would treat their ideas on the subject with respect.

My student teachers being adults, I wanted us to share a reading experience that moves through the fullest expressions of a challenging theme such as human sexuality, in a way that might challenge them the same way that an easier text might challenge a less experienced reader. Fun Home was ideally suited to exemplify certain ideas in a university teacher education environment, but not necessarily appropriate for direct application in middle grades (for some examples, see Boerman-Cornell & Kim, 2020). Although working in a graduate-level teacher education environment, I did not want us to lose the childlike excitement or satisfaction in making something, though, and the ‘Pathetic Geek Stories’ pre-reading activity I created for Fun Home generated the kind of community building and aesthetic appreciation that enabled genuinely deep critical analysis and reflection. It is my hope that my approach to these aims will inspire other teacher educators to consider how they can build meaningful lessons based on other graphic narratives in a similar way, or to consider what values are implicit in their own approach to teacher education.

Bibliography

Bechdel, Alison. (2007). Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Mariner Books.

Schneider, M. (2008). Pathetic Geek Stories. https://patheticgeekstories.com/

References

Ahmed, S. (2010). Happy objects. In M. Gregg & M. J. Seigworth (Eds.), The Affect Theory reader (pp. 29-51). Duke University Press.

Austring, B. D., & Sørensen, M. C. (2006). Æstetik og læring: Grundbog om æstetiske læreprocesser [Aesthetics and learning: Textbook on aesthetic learning processes]. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Biesta, G. (2014). The beautiful risk of education. Routledge.

Bland, J. (2018). Introduction: The challenge of literature. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8-18 year olds (pp. 1-22). Bloomsbury Academic.

Boerman-Cornell, W., & Kim, J. (2020). Using graphic novels in the English language arts classroom. Bloomsbury Academic.

Bordelle, A. (2015). Multimodality 101: Graphic novels and multimodal composition. In M. Miller (Ed.), Class, please open your comics: Essays on teaching with graphic narratives (pp. 91-102). McFarland & Company.

Brekke, B. (2016). Kreativitetens næringskjede: Estetiske arbeidsformer i lærerutdanningen [The food chain of creativity: Aesthetic forms of work in teacher education]. [Master’s thesis, University of Agder]. Agder University Research Archive. https://uia.brage.unit.no/uia-xmlui/handle/11250/2414164

Eisenmann, M., & Summer, T. (2020). Multimodal literature in ELT: Theory and practice. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 8(1), 52-73.

Fish, S. (1982). Is there a text in this class? The authority of interpretative communities. Harvard UP.

Goldstein, B. (2016). Visual literacy in English language teaching: Part of the Cambridge Papers in ELT series. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/us/files/7015/7488/7845/CambridgePapersInELT_VisualLiteracy_2016_ONLINE.pdf

Habbeger-Conti, J. (2021). Where am I in the text? Standing with refugees in graphic narratives. Children’s Literature in English Language Education,9(2), 52-64.

Hanssen, J. A., & Jensvoll, M. (2020). Linking creativity and criticality: Engagement with literary theory in middle grades English education. In G. Neokleous, A. Krulatz & R. Farrely (Eds.), Handbook of research on cultivating literacy in diverse and multilingual classrooms (pp. 261-287). IGI Global.

Hoff, H. E. (2018). Intercultural competence. In A. B. Fenner & A. A. Skulstad (Eds.), Teaching English in the 21st century: Central issues in English didactics (pp. 67-89). Fagbokforlaget.

Iversen, L.L. (2012). Learning to be Norwegian: A case study in identity management. Waxmann Verlag.

Lutnæs, E. (2018). Creativity in assessment rubrics. In E. Bohemia, A. Kovacevic, L. Buck, P. Childs, S. Green, A. Hall & A. Dasan (Eds.), DS 93: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E & PDE 2018) (pp. 506-511). Oslo Metropolitan University. https://www.designsociety.org/publication/40842/creativity+in+assessment+rubrics

Pope, R. (1995). Textual intervention: Critical and creative strategies for literary studies. Routledge.

Reichl, S. (2009). Cognitive principles, critical practice: Reading literature at university. Vienna UP.

Ricoeur, P. (1980). Narrative time. Critical Inquiry, 7(1), 169-190. ww.jstor.org/stable/1343181

Ricoeur, P. (1985). Time and narrative: Volume 2. University of Chicago Press.

Simon, M. (2016). Collective reading and communities of practice: Teaching Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy, 26(2), 139-156.

Steig, M. (1989). Stories of reading: Subjectivity and literary understanding. Johns Hopkins UP.

The Norwegian Directorate of Education (Udir). (2019). Core Curriculum Competence in the Subjects.Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/prinsipper-for-laring-utvikling-og-danning/kompetanse-i-fagene/?lang=eng&curriculum-resources=true

Wagenschein, M. (2008). Teaching to understand: On the concept of the exemplary in teaching (J. K. Saltet & C. Holdrege, Trans.). The Nature Institute. (Original work published 1956). https://www.natureinstitute.org/article/martin-wagenschein/teaching-to-understand

Appendix: Post-reading discussion questions for Fun Home

Introductory questions about the format of Fun Home:

- How does the chapter organization of Fun Home work? Is the story told sequentially? Why does Bechdel move forwards and backwards in time? What purpose does that have?

- How would you describe the font of Fun Home? How do elements of the text such as the font Bechdel uses influence its meaning?

- What does the limitation of colour in Fun Home achieve?

- How does Bechdel incorporate other literature into her story, and how does it help her establish her voice?

Secondary questions about the context of Fun Home:

- What is a perfect family? The one you have, or the one you want? Is there any such thing?

- How do you feel about openly discussing sexuality at school? What are some advantages and disadvantages to sexuality as an ELT classroom theme?

- Where do you think Bechdel blurs the lines between herself as a character and herself as an author? Are there any ethical boundaries to this?

- Based on the interview, can you compare Bechdel’s authorial/artistic process to the kind of preparation you as teachers must do? What do you take away from Bechdel’s discussion of her process in terms of your professional development and responsibilities?

- How will you as a teacher balance free speech with maintaining a respectful classroom environment and good order?