| Child Empowerment and Safeguarding in the UAE: The Role of Picturebooks for Emirati Children

Sarah L. Nesti Willard and Fawzia Gilani-Williams |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This paper presents a reflective ethnography documenting the creation and use of picturebooks in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), aimed at supporting the safeguarding of children within English Language Teaching (ELT) contexts for primary and lower secondary students. It explores the collaboration between an author and an illustrator in developing books that align with the principles of Wadeema’s Law, the Child Protection Law of 2016. These picturebooks are designed to safeguard children’s psychological and emotional well-being, facilitate bibliotherapy, and promote learning across curricula. They serve as informational, inspirational, and discussion texts that contribute to raising awareness of child rights, particularly in the context of Emirati culture and values. Our paper discusses five picturebooks, three of which were published by the UAE Ministry of Community Development. Through this collaborative ethnography, the study focuses on the development, content, and implementation of these books as pedagogical tools to foster discussions on child safeguarding and support the broader objectives of child protection in the UAE.

Keywords: Bibliotherapy, Child Protection Law, Emirati children’s literature, safeguarding, Wadeema’s Law

Sarah L. Nesti Willard is Coordinator of Visual Studies and Creative Industries, Department of Media, United Arab Emirates University, UAE. She is also a children’s picturebook illustrator and muralist.

Dr Fawzia Gilani-Williams is a scholar of Islamic children’s literature with international experience in K-12 education. She is also a children’s author and serves as an editor for the Eid Stories Institute and Project You in the UAE.

Introduction

In 2020, we were presented with an opportunity to contribute to an initiative led by the UAE Ministry of Community Development (MOCD). This project focused on creating safeguarding literature aimed at addressing abuse, specifically designed for classroom use in Emirati lower and middle schools. As part of this groundbreaking effort, we consider ourselves among the pioneer authors and illustrators of children’s safeguarding literature within the UAE. In 2022, we shared our findings from this collaboration through a presentation at the Child and the Book Conference held in Valletta, Malta. Our presentation included a discussion of our work alongside that of a fellow author whose book, The Wadeema Law (Al Khayat, 2020), was previously featured at the International Research Society for Children’s Literature Conference, Chile, in 2021. This shared focus on children’s rights further informed our approach to the project. With experience as cluster librarian and picturebook illustrator, we feel equipped to critically examine and document the evolution of safeguarding narratives within Emirati children’s literature. Our longstanding engagement with schools and students provides us with a deep understanding of their experiences, which we try to convey through our storytelling and creative work.

Development of Children’s Literature in the UAE

As Meek Spencer (2001) noted, ‘the history of children’s literature … begins, like all other literatures, in the oral tradition of singing and storytelling’ (p. 95). Historically, culture was transmitted orally rather than visually, also in the Arab World (Mdallel, 2004). During the period of industrialization, foreign literature was imported and widely disseminated, particularly for educational purposes (Hudson, 2011, p. 128). Since the formation of the UAE in 1971, Emirati children’s literature has continued to develop and expand.

At the beginning of the 21st century, animated picture-making was publicly encouraged across Gulf countries. As a result, numerous local publishing houses, including those specializing in children’s books, were established. The publishing sector remains in continuous growth (Gulf News, 2022). Many of these publishers are creating stories and characters that help children develop a sense of belonging, visibility, and a deeper understanding of their society and identity (Al-Jazi, 2018, pp. 131–133; Gilani-Williams, 2018; Gjylbegaj, 2019, p. 138; Nesti Willard & Gilani-Williams, 2022; Sowa & Lacina, 2011, pp. 397–398).

Children’s Safeguarding Picturebooks in the UAE

Children’s safeguarding picturebooks aim to address the need for age-appropriate texts that teach prevention concepts and provide support for young children who may be at risk of or have already experienced abuse (Lampert, 2011, pp. 177–178). Sensitive topics are typically discussed through books in schools to help children become aware of potential societal dangers. This type of literature is currently experiencing growth in the UAE: great efforts are being made to introduce more culturally sensitive and relevant safeguarding literature in various educational settings, and while literature addressing abuse and societal issues is still limited, there is growing openness and development in safeguarding literature for Emirati children (Nesti Willard & Gilani-Williams, 2022). This growth in literature is attributed to the UAE’s large young population. As of 2025, 15% of the UAE’s citizens are reported to be below the age of 14, amounting to approximately two million children (GMI Research Team, 2025).

Children are highly cherished and well-looked-after in Emirati families (Noaves Machado Stocker et al., 2014, p. 368), and their education is supported by governmental institutions (Alhosani, 2022, pp. 287–288). However, according to Geranpayeh (2017), when children experience abuse or neglect, there is often a tendency to resolve the issue within the family to avoid community shame, which can exacerbate trauma instead of facilitating a healing process. Hence, to further protect children’s well-being, the UAE acceded to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations Human Rights, 1989) in 1997 and passed national laws that uphold the rights of children. Since then, children’s safeguards in the United Arab Emirates have been considered a keystone in the State’s strategic planning (Permanent Committee for Human Rights, 2025), along with the development of awareness programs and related literature.

The Wadeema Law and its campaigns

Child Protection Law No. 3, commonly referred to as Wadeema’s Law, is a pivotal legal framework in the UAE that underscores the nation’s commitment to child welfare and protection. Enacted in response to the case of Wadeema, an eight-year-old girl whose death highlighted the need for strengthened child protection measures, this law ensures the rights of children across various domains, including physical, social, cultural, and educational well-being (The National, 2016).

To further enhance child safety, the Ministries of Happiness and Wellbeing, along with the Ministry of Community Development, have launched extensive awareness campaigns focused on promoting child well-being, empowerment, and personal development (World Government Summit, 2019, p. 67). These initiatives have contributed to the creation of safeguarding literature, which is now accessible in schools and libraries nationwide. Such resources serve as valuable bibliotherapy tools, supporting children’s understanding of their rights and fostering a culture of safety.

Over the past two years, various workshops have been conducted to equip children with essential knowledge and skills for addressing challenging situations. One notable initiative is the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism’s I Do Not Accept campaign, launched in 2022 for children aged three to ten. This programme empowers young learners with age-appropriate strategies for responding to unsafe situations. Additionally, in December 2022, the UAE Cabinet introduced Decree Number 3/3, The National Child Protection Policy in Educational Institutions, which sets out twelve key objectives aimed at strengthening child protection measures and fostering a safe and nurturing learning environment (UAE, 2025).

Further reinforcing these efforts, the Early Childhood Authority (ECA) collaborated with the Zayed Central Public Library in January 2023 to deliver a specialized workshop for librarians. This training introduced the Student Protection Policy and the Handling Maltreatment Concerns Guide, designed to support schools and nurseries in Abu Dhabi. According to a Child Welfare Senior Specialist for the ECA, this guide was scheduled for release in 2023, with collaborative input from key entities such as ECA, Abu Dhabi Department of Education and Knowledge (ADEK) and the United Arab Emirates Ministry of Education (MoE). The phased implementation of these resources aimed to ensure that every child benefited from a supportive and secure educational environment.

Another significant initiative is the Ministry of Education’s Child Protection Unit (CPU), which provides a dedicated response mechanism for incidents in both private and public schools. All professionals working with children are now trained as mandatory reporters, reinforcing a proactive approach to child safety (UAE, 2025). Additionally, the CPU, in collaboration with the Ministry of Interior’s Child Protection Centre, has established accessible reporting channels, including phone hotlines and email services, enabling children and adults to seek assistance when needed (United Arab Emirates Ministry of Education, 2025).

Bibliotherapy and its benefits

Bibliotherapy is the use of reading as a therapeutic tool to facilitate personal healing and development. Often utilized in treatment approaches, bibliotherapy is particularly effective in educational settings through a specific form known as developmental bibliotherapy, which addresses sensitive childhood and adolescent issues (Lindberg, 2021, p. 2). According to specialists, bibliotherapy is an effective way to treat personal issues by assigning a book related to the trauma, which the individual must discuss with a therapist (ibid.). The patient relates to the protagonist and reflects on how the character handles similar issues, fostering empathy and problem-solving skills.

In the UAE, where the language of instruction in most schools is both Arabic and English, due to the adaptation of the international curriculum (Goe et al., 2020, p. 1), bibliotherapy books are often read in the language in which the book is written. In classrooms, qualified teachers guide small groups of children through stories, helping them confront and understand their fears (Pardeck, 1995, p. 83), initiating healing processes and personal development (Bruneau & Tucker, 2023, p. 191). The positive effects of bibliotherapy are evident in a 2017 study conducted in Brazil, which revealed that young children, when shown picturebooks depicting abuse, could relate to the content and more easily articulate their feelings and experiences. The study concluded that storytelling supported by specialized books on abuse prevention is an effective method for teaching self-protection skills (Soma & Williams, 2019, pp. 197-98). As Gilani-Williams (2016) notes, ‘Bibliotherapy involves the actualisation of self-transformation through a character’ (p. 155). This concept emphasizes the power of literature to not only help children process and understand their emotions but also inspire meaningful self-reflection and personal growth through the characters they encounter.

Safeguarding readings and cultural challenges

While children’s safeguarding picturebooks gained prominence in Western countries during the early 1980s (Lampert, 2011, pp. 177–178), the Gulf region has traditionally focused on literature that celebrates religion, history, folklore, and significant social themes such as migration and resilience (Gultekin & May, 2019, pp. 628–630). This literary landscape reflects a deep appreciation for cultural heritage and values. Additionally, authors have been mindful of addressing sensitive topics in a way that aligns with societal norms and traditions, ensuring that children’s literature remains both enriching and appropriate (Gobert, 2015, pp. 113–114).

The Quran is often overlooked for what it contains regarding the safeguarding of children, yet it offers several verses that emphasize the protection, care, and well-being of children, highlighting the importance of safeguarding their rights. For instance, Surah Al-Isra (17:31) prohibits the killing of children, emphasizing the sanctity of life and the protection of children’s well-being. Surah An-Nisa (4:9) stresses the responsibility of guardians to protect vulnerable children, ensuring their safety and security. In Surah Al-Baqarah (2:220), the Quran calls for the care of orphans with justice and integrity, while Surah Al-Baqarah (2:177) advocates for the care of orphans and the vulnerable as part of righteousness. These verses collectively provide a strong foundation for the protection of children, promoting justice, kindness, and the safeguarding of their rights within society.

Recognizing the importance of child safeguarding, educators and researchers in the UAE have explored ways to introduce meaningful discussions on complex topics while maintaining a culturally responsive and developmentally appropriate approach. In 2016, El-Sakran examined how sensitive subjects are addressed in Emirati schools, highlighting the thoughtful consideration given to topics such as personal safety and well-being. Similarly, Paul Hudson’s experiences with students learning English emphasize the need for carefully guided discussions, led by educators and specialists, to ensure that children receive the right support and understanding (El-Sakran, 2017, pp. 9–12; Hudson, 2011, p. 128).

A significant milestone in advancing children’s rights literature in the UAE was the Dubai Courts’ initiative to commission Emirati author Maitha Al Khayat to create a comprehensive book on children’s rights (Zacharias, 2020). This government-led effort has paved the way for a series of child safeguarding books, enriching the literary landscape with resources that empower young readers while respecting cultural values. These initiatives mark a positive and proactive step in ensuring that children’s well-being and rights are effectively represented in literature, fostering a culture of awareness, education, and empowerment.

In line with this development, the September 2024 | Version 1.1 | ADEK School Safeguarding Policy (ADEK, n. d.) emphasizes the importance of safeguarding in schools. The policy outlines key requirements, including that schools must develop and implement a Safeguarding Policy and actively communicate this to the whole school community. At a minimum, the Safeguarding Policy must include elements such as clear guidelines on child protection, strategies for addressing abuse, and specific measures to support the well-being of students. These policy requirements ensure that safeguarding becomes a fundamental part of the educational environment, reinforcing the commitment to children’s safety and rights within the UAE educational framework.

Study Scope and Methods

Following the example of Maitha Al Khayat’s Wadeema’s Law, additional titles have been commissioned to reinforce the children’s rights as outlined in Wadeema’s Law. The books discussed in the following sections serve as safeguarding resources in English as a Second Language (ESL) classrooms across Emirati schools.

This study discusses the development of children’s safeguarding literature specifically created for Emirati children and provides an analysis of selected texts. Through textual and visual analysis, we demonstrate that the books produced for Emirati children reflect and elaborate on the regulations stated in Child Protection Law No. 3 while embedding UAE cultural values. This paper not only celebrates the existence and classroom implementation of Emirati children’s safeguarding literature but also offers insights into how these books are perceived by educators and children. Additionally, it informs future stakeholders about areas for improvement to ensure the continued development of high-quality safeguarding literature. The selection of books for this study was based on their availability rather than a pre-determined framework of existing publications. One is by Maitha Al Khayat, a pioneer of children’s Emirati literature, and the other four are books in which the authors of this paper have contributed.

To understand how these books are received, we shared the resources with a study group and conducted open-ended interviews with selected parents. We chose to focus on feedback within a mother-child context rather than a classroom setting, as research suggests that classroom environments can sometimes feel formal or restrictive, potentially limiting authentic emotional responses (Peters & Skirton, 2013, p. 254). The mother-child feedback model, on the other hand, provides valuable insights into cultural identity, parental expectations, and the impact of safeguarding literature within the home environment (ibid.). Furthermore, we conducted an open-ended interview with Maitha Al Khayat to gain deeper insights into one of the selected books. In addition, discussions of activities conducted in libraries with students and sessions in whole school settings are also incorporated in this study. Written consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Wadeema’s Law (Al Khayat, 2020)

Written in Arabic, Maitha Al Khayat’s Wadeema’s Law has been available as an open access advocacy book shared within governmental Emirati schools since 2020 (The National, 2020). The book, with its unusual format and approximately 80 pages in length, explains children’s rights in a way that resonates with local Emirati and Islamic culture. The book, initially commissioned to Al Khayat by Dubai Court, follows the story of two siblings, Sultan and Wadeema, who visit the court to learn about the laws that protect children. Al Khayat frequently visits schools and reads a few pages to young pupils, accompanied by court professionals who help explain concepts through games and related activities.

The first section addresses the right to have a name, emphasizing that every child should have a birth certificate, be registered with the government, and be affiliated with their father, who grants them nationality through the country to which they belong (Figure 1). The next section covers family rights, which include the duty to be with one’s family, to communicate openly with its members, and to express one’s thoughts and opinions.

Figure 1. A boy holding a passport.

Figure 2. A boy holding a Laban drink.

From The Wadeema Law Book by Maitha Al Khayat ã 2020. Published by Dubai Courts. Reproduced with the illustrator’s & author’s permission.

The following sections focus on mental and physical health (Figure 2), the need for foster families for orphaned or abandoned children, and the importance of nurturing children’s interests and developing their skills. The book reminds children that some content on TV, in games, or at the cinema may be culturally and socially inappropriate for them. If they find any content disturbing, they should avoid it and inform their parents. Children are encouraged to be educated with strong moral values from a young age (Akraan AlAli, 2020, p. 18; Al-Jazi, 2018, p. 133). The book concludes by explaining the right to protection from any form of abuse. It addresses issues such as child mistreatment, exploitation, lack of education, and denial of basic care. It cautions that these situations can lead to the loss of self-esteem, hatred, and violence. Visually, the book is characterized by a minimalist layout, where a blurred watercolour background is paired with illustrations of children and families representing various ethnicities and faiths. This design choice reflects the UAE’s diverse demographic and reinforces the values of tolerance and inclusivity (Akraan AlAli, 2020, p. 19). The text is succinct, allowing the illustrations to dominate the page and enhance the narrative.

Looking But Not Seeing (Gilani-Williams & Nesti Willard, 2020)

Article 1 of Wadeema’s Law explicitly prohibits the ‘deliberate use of force against any child by any individual or group that would lead to actual harm to the health, growth, or survival of the child’. This legal provision is addressed in our picturebook Looking But Not Seeing, which was commissioned by the UAE Ministry of Community Development in 2020. Aimed at children between the ages of 12 to 15, the text is also adapted for English as a Second Language (ESL) speakers and shared with students as an online resource.

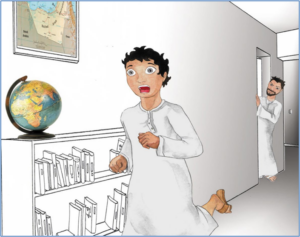

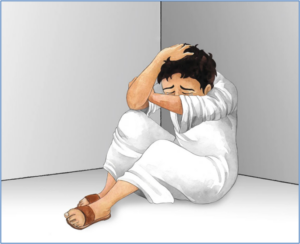

The plot revolves around a teenage boy, Saeed, who, at his uncle’s party, meets a boastful man who has made a mistake in his geographical knowledge. Saeed corrects the man, but a dispute starts. To prove his point, Saeed takes the man to a room where a globe is located. As they walk along a hallway, the man suddenly pulls Saeed inside a room and physically assaults him. Saeed eventually manages to free himself and runs out of the house (Figure 3). The boy does not disclose his traumatic experience with anyone and becomes increasingly anxious and troubled, as triggers remind him of his attacker (Figure 4). His family and his teachers are concerned about his change in attitude, but little is done until a new and experienced teacher arrives and provides Saeed with the help he needs. Eventually, Saeed speaks to the school’s psychologists, and, with each therapeutic session, he learns to face his anxieties. In time, Saeed regains some normalcy and eventually goes back to his own self: he is cheerful again and enjoys school, his family, and his friends. The story concludes with Saeed’s brother seizing the attacker and bringing him to justice.

This narrative serves as a powerful example of how literature can effectively address sensitive topics such as abuse, functioning both as a bibliotherapy tool for young readers and as a means of raising awareness about child protection laws.

Figure 3. Saeed running out of a room.

Figure 4. Saeed crying.

From Looking But Not Seeing by Fawzia Gilani-Williams & Sarah L. Nesti Willard ã 2020. Published by Ministry of Community Development (MODC). Reproduced with the illustrator’s & author’s permission.

Be the Best You Can Be! (Gilani-Williams & Wati, 2020)

Article 15 of Wadeema’s Law states, ‘The child’s custodian shall assume the responsibilities and obligations entrusted to him/her in raising, caring, guiding, and developing the child in the best way’. This principle is highlighted in Be the Best You Can Be!, a story that underscores the importance of parental involvement in a child’s life. The narrative, presented as an online resource, a 25 slide-long PDF, with text compressed on the right and the illustrations on the left, follows 15-year-old Ali, who feels emotionally neglected by his busy parents despite his achievements in Taekwondo. Ali excels in the sport, eventually becoming a champion, but his parents are rarely present to witness his victories. In search of acceptance, Ali begins associating with the wrong crowd and frequently finds himself in trouble at school. After a threat of expulsion, his parents decide to move him to a new school, where he meets Abdullah, another Taekwondo champion. Over time, Ali and Abdullah develop a strong friendship, and through Abdullah’s invitations, Ali becomes acquainted with Abdullah’s family. This exposure allows him to witness firsthand the positive and supportive family dynamics that were absent in his own life (Figure 5).

Figure 5. An Emirati family eating. From Be the Best You Can Be! by Fawzia Gilani-Williams & Gisna Wati ã 2020. Published by MODC. Reproduced with the illustrator’s & author’s permission.

Ali observes that Abdullah’s family, in contrast to his own, consistently offers encouragement and support, creating a nurturing environment that fosters positive growth. This sharp contrast with his own parents’ emotional absence begins to weigh heavily on him. Struggling with feelings of neglect, Ali falls back into his rebellious ways, and things take a downward turn when he reunites with his delinquent friends at a mall (Figure 6).

The friends dare Ali to steal, and he ultimately breaks the law. When the police are called, the incident becomes a wake-up call for Ali’s parents. They realize the gravity of the situation and recognize the need to be more present and supportive in their son’s life. Motivated by this realization, Ali’s parents commit to being there for him. When he wins the championship and sees his parents in the audience, cheering him on with genuine encouragement and support, his heart soars (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Ali at the mall

Figure 7. Ali as a winner

From Be the Best You Can Be! by Fawzia Gilani-Williams & Gisna Wati ã 2020. Published by MODC. Reproduced with the illustrator’s & author’s permission.

Dima’s Amazing Invention (Gilani-Williams & Shmorgan, 2020)

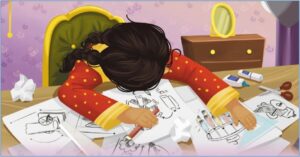

Article 2 point 8 of Wadeema’s Law states that the child should be involved in aspects of community life and develop abilities that allow the child to be ‘raised on the love of work, initiatives, legitimate earning and self-reliance’. Dima’s Amazing Invention effectively aligns with these principles by promoting the idea of young girls taking an interest in science and creativity, while also highlighting the significance of persistence and resilience. The book, an online resource comprising 25 slides, traces Dima’s journey from infancy (Figure 8) to her participation in a Science Fair competition (Figure 9). Early on, Dima struggled with perseverance, often giving up when faced with challenges. However, with the unwavering support and encouragement of her parents – who repeatedly remind her, ‘If at first you don’t succeed, try, try, and try again’ – Dima learns to tackle problems head-on and remain determined.

In alignment with Article 2, point 2, which states that children should be raised to follow Islamic values and take pride in their national identity, Dima’s Amazing Invention incorporates moments where Dima is depicted in prayer: by seeking guidance from God, Dima draws strength and inspiration to overcome obstacles. Eventually, she wins the Science Fair competition and is asked to share her work with university students. Her success brings recognition and underscores the story’s message of self-empowerment, faith, and the pursuit of excellence.

Figure 8. Dima as a newborn

Figure 9. Dima collapses on her books

From Dima’s Amazing Invention by Fawzia Gilani-Williams & Natalia Shmorgan ã 2020. Published by MODC. Reproduced with the illustrator’s & author’s permission.

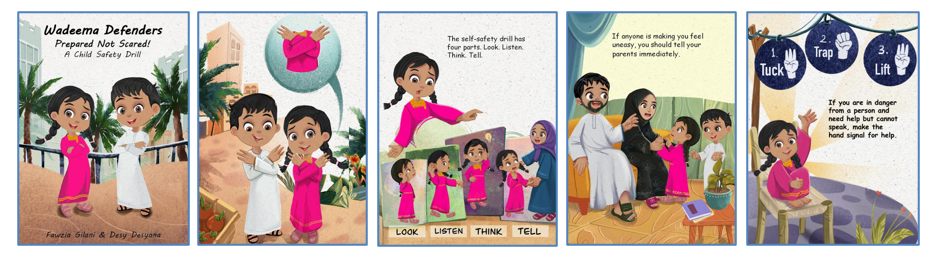

Wadeema Defenders (Gilani-Williams & Desyana, 2023)

Wadeema Defenders ‘Prepared, Not Scared’ Child Safety Drill aligns with Article 2, Point 6 of Wadeema’s Law, which emphasizes the importance of educating children about their rights, particularly in relation to their protection from abuse and neglect, in a manner that is clear and accessible. The program provides children with a straightforward, age-appropriate approach to understanding their personal safety and rights. Using simple and memorable arm and hand gestures, Wadeema Defenders (Figure 10) – an online resource shared in government school classrooms during the programme’s implementation – empowers children to recognize and assert their right to protection in situations where they may feel threatened.

Figure 10. From Wadeema Defenders by Fawzia Gilani-Williams & Desy Desyana (2023). Reproduced with the illustrator’s & author’s permission.

The Wadeema Defenders activity was created to help children develop awareness and practical skills to protect themselves in unsafe situations. Through engaging and age-appropriate activities, children can learn essential safety concepts in a way that is memorable and easy to apply in real-life scenarios.

Figure 11. A Wadeema Defenders’ school activity poster

The gestures performed by the characters are mimicked by children and provide a non-verbal means to signal discomfort or seek help, ensuring they can communicate their needs effectively, even when verbal communication is not possible. This ensures that children can navigate potential threats without confusion or fear, reinforcing their right to safety in an accessible way.

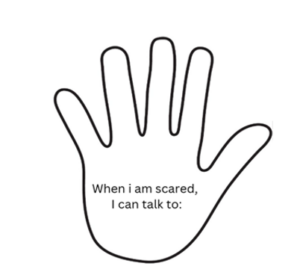

The four-step Look, Listen, Think, Tell process serves as an easy-to-understand framework for children to assess their environment and make informed decisions to protect themselves. These steps are designed to be simple enough for children to grasp, yet comprehensive enough to provide valuable guidance on recognizing and responding to potential risks. Wadeema Defenders also incorporates engaging resources such as educational songs and practical scenarios, which are designed to reinforce the programme’s principles in a fun, memorable way. This approach ensures that children not only understand their rights but are also equipped with the knowledge and tools to exercise those rights in real-life situations. Maseeha Behra and Honeylette Nablo collaborated to create engaging activities for students, centred around the key concepts of the safety drill. One activity involved an outline of a hand where students could write the names of five trusted individuals they could turn to if they felt uncertain, fearful, or were experiencing bullying (Figure 12). The use of Emirati-style characters helped the students connect with the scenarios, making it easier for them to identify potential dangers. This exercise also encouraged students to share their personal experiences of uncertainty, fear, or bullying, which not only empowered them but also created an opportunity for peer learning, as they could inform and support each other in identifying and addressing unsafe situations. Additionally, the activity contributed to the development of English language skills, particularly in speaking and listening, as students discussed their feelings and experiences.

Figure 12. Help gesture

Discussion of the Picturebooks and Findings

The texts discussed in this chapter highlight the potential threats of neglect, abuse, and perseverance. The author of Wadeema’s Law Book, Al Khayat, shared that illustrating the abuse section was the most challenging, she was concerned that it might frighten children (Al Khayat, personal communication, February 8, 2022). Al Khayat, however, overcame this discomfort through direct and clear visual representation. She drew the characters looking into the eyes of the reader, creating a visual dialogue that draws the reader into the narrative. This technique is not commonly used in picturebooks, where multiple perspectives are usually illustrated (Unsworth, 2014, pp. 94–96). The direct gaze has been employed throughout history in classical art to create emotional engagement, using eye contact to evoke pathos and drama (Argan, 1993, p. 125). This approach allows readers to connect more deeply with the characters, making them feel that they too could be part of the story. This aligns with bibliotherapy, which encourages children to empathize and place themselves in relatable situations (Soma & Williams, 2019, pp. 197–198). Through the minimalist text, strong moral and societal values reflective of the local culture are conveyed to readers. For instance, the selection of a newborn’s name is tied to family lineage and Islamic heritage, emphasizing the importance of choosing a meaningful and spiritually significant name (Sharma, 1998, pp. 153–154). Additionally, children are taught to understand values and discern between ‘good’ and ‘immoral’ actions, with particular attention given to influences such as TV programmes and video games. According to the author’s testimony, due to the length of the book, a few selected pages are read at school, and further reading at home is recommended to parents.

Looking But Not Seeing (Gilani-Williams & Nesti Willard, 2020) addresses the topic of abuse, but the protagonist’s experience is left intentionally vague. The line ‘no one knows what happened in that room’ invites readers to imagine the possible trauma the child might have endured. The story is told from the child’s perspective, using sensory cues – sounds, smells, and sensations – to trigger Saeed’s memory. These sensory details focus on emotions and mental states, which may be relatable to children who have experienced abuse (Ehlers & Clark, 2000, p. 352). This literary technique delicately introduces a sensitive issue in a culture where such topics are often not discussed openly (Ashencaen Crabtree, 2008, p. 583). Moreover, the book’s minimalist artwork fits the target audience, using simple illustrations that support the narrative and clarify unfamiliar words for Emirati children without being overly elaborate. Parental feedback revealed that this book delivers awareness of symptoms of mental illness and physical sickness with abuse, and parents need to be aware of this. On the other hand, children felt compelled to ask more questions on the modes of physical abuse, which were openly discussed in this one family setting.

Be the Best You Can Be! (Gilani-Williams & Wati, 2020) emphasizes the importance of emotional support and parental guidance. It shows how children, lacking access to caregivers and direction, may turn to deviant behaviour. It outlines the negative consequences of unchecked behaviour, illustrating how it can have long-lasting effects on the child. The book also underscores the importance of communication and partnership between parents and the child’s school, advocating for a united approach to child development and behaviour management.

From a structural perspective, Be the Best You Can Be! follows a Proppian storyline, clearly illustrating the triumph of good over evil. It also reinforces Islamic values of collective life and generosity, particularly through the depiction of Abdullah’s family, whose parents are supportive and encouraging, in contrast to Ali’s family, who are busy and inattentive. The illustrations emphasize the concept of the ideal Emirati family as a societal model, reinforcing the idea of a strong family nucleus, which is central to Emirati children’s literature (Al-Jazi, 2018, p. 137; Michalak-Pikulska, 2012, pp. 98–100). As the protagonist, Ali, questions his parents’ actions, the story prompts reflection among real-life parents, some of whom recognize that children are keen observers who critique their parents’ behaviour. One mother, for example, noted that the story serves as a reminder for parents that life priorities should not be neglected, with the comment, ‘A child’s well-being is more important than having money’.

Dima’s Amazing Invention (Gilani-Williams & Shmorgan, 2020) focuses on persistence and resilience, teaching children the value of overcoming difficulties and not giving up. Dima exemplifies dreaming, believing, and achieving, with the support and encouragement of her parents. The story highlights how problem-solving and persistence lead to success, providing a positive model for children. A notable visual innovation in the book is the portrayal of an Emirati father holding his daughter, challenging the stereotypical view of women as the sole caregivers in patriarchal societies. This illustration reinforces the idea that both parents share equal responsibility in raising their children, breaking down gendered expectations in the process. This story was particularly liked by girls, and most children pointed out that Dima’s mother does not look like an Emirati woman, due to the character’s fair eyes, while a mother remarked that the way of representing Emirati attire was stereotyped, assuming that the illustrator was probably a foreigner. She remarked that Emirati heritage had so many more styles of attire, which go often undiscussed.

Wadeema Defenders (Gilani-Williams & Desyana, 2023) teaches children to recognize when they are in unsafe situations and how to react appropriately. One of the key principles in Wadeema Defenders is empowering children to understand that they are not alone in facing challenges, especially when dealing with situations that involve potential harm. This allows a comparison to the way Saeed’s character in Looking But Not Seeing did not seek adult assistance. Wadeema Defenders helps children understand that they must reach out to trusted adults.

In these books, there is a consistent focus on child safeguarding, emotional support, resilience, and the importance of guidance from trusted adults. They offer relatable and sensitive ways to engage children with complex issues, reinforcing the value of open communication, perseverance, and the recognition of their rights to safety and well-being. Sharing these books with a small study group revealed that parents, when reading these books to their children, focus on both the meaning as well as the language: if the meaning of a story is attractive, the story is read more than once, and the concept is reinforced. Parents and children assessed the English text as comprehensible and adequate for their level; however, the books’ layout, with the text concentrated on one page rather than on the full spread, was assessed as not well-integrated with the images.

Conclusion and Implications

The titles discussed in this chapter represent a small but growing body of child safeguarding literature in the UAE. These works, while differing in style, content, and message, collectively highlight the importance of empowering children through literature. Looking But Not Seeing and Be the Best You Can Be! follow a narrative structure, where the classic battle between good and evil is presented. On the other hand, Wadeema’s Law Book is more of an instructional guide for children, while Dima’s Amazing Invention serves as an empowering, inspirational text aimed particularly at girls, encouraging them to pursue fields like science.

The government’s focus on child protection is reflected in these books, which aim to empower children, educate them about their rights, and help them recognize and protect themselves from potential harm. Empowering children is a key aspect of transformative education, as it builds resilience, self-awareness, and emotional intelligence. Schools play a pivotal role in this process by incorporating literature that not only engages but also empowers young readers. It is important for educational institutions to actively include texts that foster children’s agency and resilience, especially in the context of sensitive issues such as abuse, neglect, and emotional well-being.

The current eBook and PDF formats provide useful ways for schools to share these resources. However, their reading requires parents to download it from shared resources. Parental feedback suggested the integration of physical books, flashcards, story cards, and class discussions to create a more interactive learning experience. Offering children multiple formats and methods of engagement – such as hands-on activities – would greatly enhance their retention and comprehension, providing a more well-rounded and immersive educational experience. Furthermore, a more standardized text-image layout and a 32-page book length is recommended. In short, while these books are spreading important safety messages, there is potential to develop them further. By making these thoughtful adjustments, we can ensure that children not only learn about safety but do so in a way that is engaging, memorable, and accessible.

Despite the hesitancy sometimes displayed by authors and illustrators in tackling delicate topics, these books represent a vital step in developing a literature genre that supports child safeguarding in the UAE. It is encouraging to see that this genre is growing in importance and that parents take an active role in advocating for child protection. Books read at home can provide an indirect means of addressing sensitive topics, helping children relate to characters and situations that may not be directly applicable to their own lives but offer valuable lessons in empathy and resilience (Lindberg, 2021, p. 1).

The use of bibliotherapy has long been an established strategy in clinical settings and is increasingly being promoted in schools and by parents as a means of addressing childhood issues. While the UAE government is beginning to champion this literature, there is a pressing need for publishers to contribute to this genre, ensuring that more safeguarding books are available in schools and libraries. These books play a critical role in supporting children who are dealing with emotional challenges, offering them both guidance and comfort in navigating difficult situations. By expanding the availability of such resources, we can better safeguard children’s well-being and foster their emotional resilience.

While this article highlights the emergence of child safeguarding literature in the UAE, further research is needed to assess its impact on children. We recommend that studies in safeguarding, child development, and education evaluate how this literature influences children in schools across the UAE. By exploring the effects of these empowering texts, the UAE can nurture a generation of resilient, self-aware children ready to face life’s challenges. In conclusion, this article underscores the importance of picturebooks in supporting child safeguarding within ELT contexts. These books align with Wadeema’s Law, promote emotional well-being, and encourage discussions on child rights. By integrating bibliotherapy, they raise awareness of safeguarding while reflecting Emirati culture and values, ultimately enhancing education and advancing child protection efforts.

Bibliography

Al Khayat, Maitha (2020). Wadeema’s Law. Dubai Courts Publisher.

Gilani-Williams, Fawzia & Nesti Willard, Sarah L. (2020). Looking But Not Seeing. Dubai: Ministry of Community Development (MODC).

Gilani-Williams, Fawzia & Shmorgan, Nataila (2020). Dima’s Amazing invention. Dubai: Ministry of Community Development (MODC).

Gilani-Williams, Fawzia & Wati, Gisna (2020). Be the Best You Can Be! Dubai: Ministry of Community Development (MODC).

Gilani-Williams, Fawzia & Desyana, Desy (2023). Wadeema Defenders. Dubai: Ministry of Community Development (MODC).

References

Abu Dhabi Department of Education and Knowledge (ADEK). (n.d.). Safeguarding policy.

ADEK_S_Safeguarding-Policy_EN_v12.pdf

Akraan AlAli, M. J. (2020). Safeguarding the successful implementation of character education in the UAE (moral education). Journal of Faculty of Education Assiut University, 36(6), 15–36. https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/jfe_au/vol36/iss6/10

Alhosani, N. (2022). The influence of culture on early childhood education curriculum in the UAE. ECNU Review of Education, 5(2), 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311221085984

Al-Jazi, A. A. (2018). The ethical concepts in the Islamic education book for sixth grade basic (comparative study). World Journal of Education, 8(3), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v8n3p131

Argan, G. C. (1993). Storia dell’Arte Italiana: Da Michelangelo al Futurismo. Fabbri Editore.

Ashencaen Crabtree, S. (2008). Dilemmas in international social work education in the United Arab Emirates: Islam, localization, and social need. Social Work Education, 27, 536–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470701747808

Bruneau, L., & Tucker, J. (2023). Using bibliotherapy to spark conversations about antiracism and advocacy with Black children. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 36(3), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2022.2138592

El-Sakran, O. T. (2017). ELT teachers’ perspectives on the discussion of culturally sensitive topics in the United Arab Emirates [Unpublished MA thesis]. American University of Sharjah. https://dspace.aus.edu/xmlui/handle/11073/8862

Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345.

Geranpayeh, S. (2017, November 4). UAE gets tough on child abuse. Gulf News. https://gulfnews.com/going-out/society/uae-gets-tough-on-child-abuse-1.2118649

Gilani-Williams, F. (2018). Why is there a need for Emirati-centric children’s literature? Edarabia.com. https://www.edarabia.com/why-need-emirati-centric-children-literature-english/

Gilani-Williams, F. (2016). The emergence of Western Islamic children’s literature. Mousaion, 34(2), 113–126. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-5378cad31

GMI Research Team (2025, March 6). United Arab Emirates (UAE) population statistics (2024). Global Media Insight. https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/uae-population-statistics/#UAE_Population_2024_Key_Statistics

Gjylbegaj, V. (2019). Children’s literature and culture in the UAE. Journal of Content, Community & Communication Amity School of Communication, 9(5), 138–146.

Gobert, M. (2015). Taboo topics in the ESL classroom in the Gulf Region. In R. Raddawi (Ed.), Intercultural communication with Arabs (pp. 109–126). Springer.

Goe, L., Khalifa Alkaabi, A., & Tannenbaum, R. J. (2020). Listening to and supporting teachers in the United Arab Emirates: Promoting educational success for the nation. ETS Research Report Series. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12289

Gulf News (2022, August 3). UAE publishing sector to hit $650 million in 2030: Report: The global media and entertainment sector is set to grow to $2.4 trillion next year. https://gulfnews.com/business/uae-publishing-sector-to-hit-650-million-in-2030-report-1.89695039

Gultekin, M., & May, L. (2019). Children’s literature as fun-house mirrors, blind spots, and curtains. The Reading Teacher – International Literacy Association, 73(5), 627–635. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1867

Hudson, P. (2011). Beef and lamb. Chicken and h*m: Censorship and vocabulary teaching in Arabia. In A. Anderson, & R. Sheehan (Eds.), Foundations for the future: Focus on vocabulary (pp. 125–135). HCT Press.

Lampert, J. (2011). Sh-h-h-h: Representations of perpetrators of sexual child abuse in picturebooks. Sexuality, Society and Learning, 12(2), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2011.609048

Lindberg, S. (2021, March 21). What is bibliotherapy? Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-bibliotherapy-4687157

Noaves Machado Stocker, J., Mohammed Hasan, A., & Khairia Ghulom, A. (2014). Parent-child relationships in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 3(1), 363–374.

Meek Spencer, M. (2001). Children’s literature and national identity. London.

Mdallel, S. (2004). The sociology of children’s literature in the Arab World. The Looking Glass: New Perspectives on Children’s Literature, 8(2). https://ojs.latrobe.edu.au/ojs/index.php/tlg/article/view/177

Michalak-Pikulska, B. (2012). Modern literature of the United Arab Emirates. Jagiellonian University Press.

Nesti Willard, S. L., & Gilani-Williams, F. (2022, May 27). Wadeema’s Law and the introduction of child rights stories for Emirati children [Conference presentation]. The Child and Book Conference, Valletta, Malta.

Pardek, J. T. (1995). Bibliotherapy: An innovative approach for helping children. Early Child Development and Care, 110(1), 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443951100106

Permanent Committee for Human Rights (2025). Children’s Rights. https://pchr.gov.ae/en/priority-details/children-s-rights

Peters, J., & Skirton, H. (2013). Social support within a mother and child group: An ethnographic study situated in the UK. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12027

Sharma, K. M. (1998). What’s in a name: Law, religion, and Islamic names. Denver Journal of International Law & Policy, 26(2), 151–207.

Soma, S. M. P., & Williams, L. C. A. (2019). Livro infantil especializado como estratégia de prevenção do abuso sexual. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 21(1), 186–203. https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/psicologia.v21n1p186-203

Sowa, P., & Lacina, J. (2011). Preservice teachers as authors: Using children’s literature as mentor texts in the United Arab Emirates. Childhood Education, 87(6), 395–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2011.10523222

The National (2020, January 28). Dubai Courts and author create book on children’s rights. https://www.edarabia.com/dubai-courts-author-create-book-childrens-rights/

The National (2016, April 12). The Wadeema Case. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/wadeema-the-emirati-girl-tortured-to-death-by-her-father-1.139099

UNICEF (2024, July 31). The Convention on the Rights of the Child: The children’s version.

https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text-childrens-version

UAE (2025). Children’s safety. The Official Portal of the UAE Government. https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/justice-safety-and-the-law/children-safety/childrenssafety United Arab Emirates Government. (2023, November 22). National child protection policy in educational institutions in the UAE. https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/policies/social-affairs/national-child-protection-policy-in-educational-institutions-in-the-uae

United Arab Emirates Ministry of Education (2025). Child Protection Unit. https://www.moe.gov.ae/En/ImportantLinks/Forms/Pages/ChildProtectionUnit.aspx

United Nations Human Rights (1990). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

Unsworth, L. (2014). Investigating point of view in picture books and animated movie adaptations. In K. Mallan (Ed.), Picture books and beyond: Ways of reading and discussing multimodal texts (pp. 92–107). Primary English Teaching Association Australia.

World Government Summit (2019). Global happiness and wellbeing policy report 2019. https://www.happinesscouncil.org/report/2019/

Zacharias, A. (2020, January 28). Dubai courts and author create book on children’s rights. The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/education/dubai-courts-and-author-create-book-on-children-s-rights-1.970391