| Embedding Language-development Tasks in Lessons Based on The Magic Finger in the Primary Classroom

Sharon Ahlquist |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This article reports on a research project which investigated the impact of working with authentic children’s literature on the vocabulary development of two classes of 10–11-year-olds in Sweden. The English classes were based on Roald Dahl’s The Magic Finger. For five weeks and three lessons per week, the teacher read the book to the children and the children read some parts of the book themselves. During this time, the children worked on a range of language-focused writing tasks to support their understanding and facilitate incidental acquisition of vocabulary. The children’s performance on these tasks also provided insight into control of grammatical structures, which the learners had already been taught, and emerging features, which they had not yet encountered explicitly in their lessons. Furthermore, many children thought that they had spoken more English through engaging with the project, a view supported by their teachers. While almost all of the children liked The Magic Finger, and most enjoyed the experience of working with it, some were ambivalent about working with another authentic book in future. This would depend on the topic and the level of difficulty of the text.

Keywords: primary; pictures; task; interaction patterns; vocabulary; authentic text

Sharon Ahlquist works as a teacher educator in pre-service training programmes for primary and secondary teachers. She is the author of Storyline – Developing Communicative Competence in English, and English is Fun!, both published by Studentlitteratur, Sweden. Besides children’s literature, her research interests include the Storyline approach, and inclusive practices.

Introduction

Research in support of using stories and authentic children’s fiction in the English language classroom is increasing. Watkins (2018) makes the point that when a teacher reads to their class, they can involve the children in the narrative through questioning techniques, which check their understanding of the story and encourage the learners to predict what might happen next. It is this shared experience that is potentially memorable for the learners. Furthermore, the story provides a framework for ‘tasks which consolidate, extend and personalize the language’, which the learners encounter in the story (Brewster & Ellis, 2002, p. 202).

However, Gray (2016) notes that the textbook continues to hold a central position in language teaching. While research shows that young language learners are initially motivated by a textbook, their enthusiasm soon fades if this is the only resource they encounter (Enever, 2011). Since research also highlights a strong link between motivation and language learning (Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; Lamb, 2017), it is reasonable to suppose that many learners do not achieve their full potential when textbooks are the only resource in their lessons.

This article reports on a research project which aimed to explore the potential benefits for language development when using children’s literature in the primary English classroom. Before describing the project and presenting the findings, I will discuss the evidence-based benefits of using stories, and then consider the benefits and potential drawbacks of using authentic materials in English language learning. Finally, I will consider the role of tasks and interaction patterns in language development through the use of authentic literature.

The Benefits of Stories in the Primary English Classroom

According to Bland (2015), L2 acquisition is enhanced when children listen to stories, as this ‘plays to their strengths – particularly their aural perception and ability to learn implicitly’ (p. 184). Bland (2015, pp. 185-86), referring to what Ong (2002, p. 71) calls ‘the centering action of sound’, notes that when children listen, their attention is captured. This places demands on a teacher’s choice of text in terms of story, characters and language level. It also requires a certain ability to read aloud in the L2, regarding pronunciation, tone of voice, pace and gesture to reinforce meaning, and involve the children through question techniques to check understanding.

When children read themselves, they form images, and these images become associated with words on the page, mediating their learning of these words (Ghosn, 2013). This process of association is enhanced through the use of illustrated books or picturebooks. Whether children read, or listen to their teacher read, their concentration depends on the appeal of the story. Hence, Egan and Judson (2015) highlight the need for stories which engage the imagination and emotions.

Regarding language development, Pinter (2017, p. 99) argues that stories are ‘an excellent vehicle for teaching grammar and vocabulary’. She maintains that in the early years, young learners should learn grammar and vocabulary holistically. In stories, lexical items are encountered and recycled ‘in the context of relevant grammatical structures such as the past tense for narrative’ (Pinter, 2017, p. ibid). Stories provide rich language input, which is beneficial once learners are cognitively mature enough to start to analyze the language. Furthermore, with regard to the cognitive benefits of working with stories, ‘children have a pre-existing story template’ (Bland, 2015, p. 186), that is, they have an innate sense of narrative structure, story plot and characterization in different kinds of stories, and this trains their thinking skills. In short, there are affective, linguistic and cognitive benefits in working with fiction in the second language classroom.

Authentic Materials and Language Support in the Primary English Classroom

One alternative to using published teaching materials is to work with authentic literature, which can be defined as ‘cultural artefacts produced for a purpose other than teaching’ (Henry, Sundqvist & Thorsen, 2019, p. 76). Authentic works of fiction introduce young learners to the cultural norms and practices of the English-speaking world and beyond, as well as the English language. Even though the cultural requirement is one component of the Swedish National Curriculum for English (National Education Agency, 2011), the potential problem for second language learners lies in the linguistic level of an authentic text. This problem can be compounded in classes used to working with translation, which relies on learners knowing the meaning of every word. Introducing fiction allows the teacher to train learners to accept uncertainty, not only regarding events in a story, but also the language used to describe them.

When stories appear in textbooks, they are often too short for the L2 learner to become absorbed in the fictional world. Moreover, from a linguistic perspective, a short text might offer little challenge for the more advanced learner, while at the same time still present problems for those with less developed English. However, when readers enter the world of a story, they become familiar with the setting, characters and core vocabulary, and this familiarity supports their understanding as they continue reading. A good story will capture their interest, they will want to know more, and on reaching the end, will have the satisfaction of having read a real English book. This sense of achievement provides a boost for the learner’s self-esteem, which plays a pivotal role in maintaining motivation (Dörnyei, 2001). Conversely, when reading a succession of short unconnected texts, the young learner is back at square one every time, as they struggle with new settings, characters and vocabulary.

For children to reap the benefits of the reading experience, when using authentic texts, the teacher needs to provide scaffolding. This might be through interactive story-telling, as advocated by Watkins (2018), asking questions about what has happened, or predicting what might happen next. Another form of scaffolding is to introduce a variety of tasks based on the text, of the kind described in this paper. At the same time, longer texts offer the learner an opportunity to engage with the complexities of plot, character development and description. Literature can also promote cross-curricular work, bring the outside world into the classroom, and last but not least, provide a framework for addressing the requirements of the curriculum.

There is a growing body of research today in support of using authentic fiction in the second language classroom. For example, Kaminski (2013) has investigated how young learners made use of pictures to construct their understanding of a narrative before they read the text. Fleta and Forster (2014) have shown how children’s books can be used to initiate project work. Their study illustrates how children’s literature can forge links across the curriculum, and also the importance of creative teaching in arousing and maintaining children’s interest in a topic.

Brunsmeier and Kolb (2017) have investigated story apps to promote young learner interaction with the text and enhance learning opportunities. They conclude that when a teacher reads aloud and the learners just listen, opportunities for learning are insufficiently exploited. Unknown words might distract and cause them to lose focus. If, on the other hand, they understand the gist of the story, there is no reason for them to think about the words they are hearing. These findings can be linked to those of an earlier study by Cabrera and Martinez (2001), in which the authors found that the ability of 10-year-olds to understand a story read aloud improved through teacher mediation. The teacher involved the learners in the telling of the story, partly by adapting their own language to that of the learners, and partly through the use of gesture, repetition and questioning. Although each of the above-mentioned studies has a different focus, what they have in common is that classroom work based on a picturebook or other authentic formats led to vocabulary development and increased motivation for reading.

These findings are significant. Firstly, the young learner takes the enjoyment of having read and worked with a complete story into their next reading experience. Secondly, the increase in vocabulary learning highlights the importance of meeting new words in context and on a recurring basis. Both context and recycling are known to impact positively on language learning (Cameron, 2001). When the teacher reads the book aloud, and then the young learners read the book themselves, there are opportunities for words to be both heard and read repeatedly. This provides a dual channel for learning the target language, which is reinforced when the learners use the words in different tasks.

Tasks and Interaction Patterns

While the benefits of stories for L2 language development have been demonstrated, what is less clear is the role of interaction patterns (individual, pair and group work) and different task types. Cameron (2001) describes tasks as ‘an environment for learning’ (p. 21) and may include open tasks, such as joint-decision making, as well as closed tasks, such as information gap and jigsaw activities, sequencing, categorizing and matching. Regarding group interaction, research into cooperative learning highlights the need for each member of the group to have a specific role to play, as they may have a piece of information that is vital to the successful completion of the task (McCafferty, Jacobs & DaSilva Iddings, 2006). Where pair interaction is concerned, Storch (2001) has identified four patterns of interaction: collaborative, dominant/dominant, expert/novice and dominant/passive. In a collaborative pattern, the learners work together on the task; in an expert/novice constellation, the more advanced learner supports their partner. Where two dominant learners are supposed to work together, they do so in parallel to each other, rarely agreeing or reaching consensus; in a dominant/passive partnership, one learner makes the decisions and may do most of the work. According to Storch, the most effective patterns for learning are collaborative or expert/novice.

Working with more able peers can promote learning within the zone of proximal development or ZPD (Vygotsky, 1978). In an L2 learning context, Ohta (1995) defines this as ‘the difference between the L2 learner’s development level determined by independent language use and the higher level of potential development as determined by how language is used in collaboration with a more capable other’ (p. 96). However, this assumes that the partners understand the task, that they are willing and able to give and receive help, and that they are motivated to do their best. The inherent features of tasks engage young language learners are of interest because of their potential impact on an individual’s language learning. This was highlighted during a five-week project in which learners aged 11-13 worked with the Storyline approach (Ahlquist, 2011). In Storyline, a fictive world is created in the classroom, while the learners, working together in small groups, take on the roles of characters in the story. Developments in the story, depicted through the learners’ texts and art work, were charted on a storyboard. The learners used the target language as they developed their characters through a variety of speaking and writing tasks within the framework of the story. The young learners in this study developed in lexical knowledge, confidence in speaking, and grammatical structure through writing. The features of Storyline which were highlighted by the learners as contributing to their learning were: working in same small groups, using their imagination to create families in the story, role playing the characters, using art work, having challenging tasks, and the fact that every lesson brought something new. For these young learners, working with the Storyline approach was ‘fun’, because as one young learner states, ‘when it is fun, you learn more’.

The Project

The research project that is the subject of this article, was a qualitative case study carried out in the naturalistic context of the classroom and within a sociocultural framework. The aim of the study was to investigate the impact on vocabulary development while basing English lessons on Roald Dahl’s The Magic Finger (Figure 1), first published in 1966.

Figure 1. Cover page of The Magic Finger

The study focuses on two questions:

- What insights do the lessons based on an authentic chapter book provide into the children’s development of English vocabulary?

- How do different task types and varying interaction patterns contribute to language development and engagement with an authentic text?

Participants and context

The study involved two Grade 4 classes of 10–11-year-old Swedish students at the same school in a small town in the south of Sweden, and was carried out during the early spring of 2019. The children had been learning English for just over two years. All but two were L1 speakers of Swedish. The two who did not have Swedish as their L1 were new arrivals to the country and did not take part in the English lessons. The 34 participants were generally positive towards English lessons, and most of them used English outside school, when travelling, listening to music, watching TV, gaming or practising with family at home.

Cooperative learning was applied across the curriculum in the school, so the learners were used to working in groups and in pairs. The two classes were different from each other in some respects. Based on information from the teachers at the outset and supported by field observations during the study, the learners in Class 1 found it easier to concentrate and get on with their work; in Class 2, restless individuals and a higher rate of absenteeism meant that more time was spent recapping what had been done, getting down to work and staying focused.

Both class teachers involved in the project were experienced in the teaching of English in the upper- primary years. The classes were used to working with varied materials, including a textbook. Neither class had previously worked with an authentic English book. Since working with children’s literature is a component of the Swedish National Curriculum for English (National Education Agency, 2011), it was decided that basing lessons over a number of weeks on an authentic book would provide novelty and a challenge. We met this challenge by integrating different kinds of language-focused tasks to support understanding of the story and facilitate the learning of vocabulary. The Magic Finger was chosen for the following reasons: Roald Dahl is a major author of children’s books; the book is richly illustrated by major illustrator Quentin Blake; the plot is straightforward; and there is a limited number of characters. The story was considered likely to appeal to both boys and girls in that it contains characters of both sexes, and also in terms of its humour. As Birketveit, Rimmerheide, Bader and Fisher (2018) have found, humorous picturebooks are one area of overlap in the fiction preferences of boys and girls.

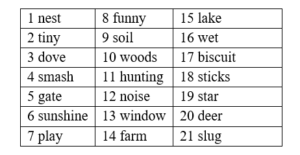

The book also provides a range of vocabulary, including many everyday words and some that are less usual, such as different kinds of birds. The target words (Figure 2) we chose for the study were selected as they supported understanding of the story and constituted a useful addition to the learners’ lexical resource. Twenty was considered a reasonable number of words for this age group; an extra word – farm – was included as an example to show the learners what to do. It was anticipated that the learners would already know some of the target words to varying degrees, for example: funny, star, window, play and farm. These familiar words would help build learners’ self-confidence and provide an important starting point for motivating them to work with the book. The learners encountered these words in the classroom while listening, reading, and in vocabulary games and activities.

Figure 2. Target words

The story is about a magical incident that happens when a young girl (who remains nameless) becomes very angry. The hunting activities of a local family, the Greggs, are the cause of her rage, and the girl’s magic finger turns them into ducks. The hunters are now the hunted. A family of human-sized ducks move into the family’s home, while the Greggs, adjusting to their new wings, attempt to build a nest and find food. Both text and pictures present the learners with an account of how the Greggs get a taste of their own medicine. The various humorous situations are described in the text and depicted in the illustrations. The story ends when the family are returned to their human form, transformed by the experience into animal lovers. The teachers read parts of the book aloud in the lessons, while the children read some parts themselves (unfortunately there were no funds to buy books for all the children, so they were only able to read excerpts). Some tasks were based on listening to the story and some were based on individual reading.

Data collection and analysis

The following data collection tools were employed in order to triangulate data and provide a detailed response to the research questions:

- Classroom observations based on field notes and photographs

- Video recordings and transcriptions of group and pair work

- A questionnaire in L1 where the learners:

- Marked a happy, neutral or sad face to indicate how much they had enjoyed working with the book

- Drew a line under yes/no/maybe respectively to indicate if they would like to work with another authentic book

- Answered a question about what they had liked best about working with the book

- Answered a question about what they did not like about working with the book

- Answered a question about what they had learnt.

- Weekly exit tickets, which elicited short reflections written in L1 about what they had learnt, and what they liked, or not, about the book and tasks.

- Pre-, post- and delayed post-tests on the target words:

- The pre-test was conducted the day before the first lesson on the book; the post-test immediately after the final lesson, and the delayed post-test two weeks later.

- The test consisted of matching the target words to the corresponding pictures. An example was provided and the teachers first checked in L1 that the learners understood the illustrations and what they had to do.

- The learners had 20 minutes for the tasks.

- Two texts (based on the same picture of two ducks on a lake), one written before the project and another in the lesson immediately after the final lesson.

- The learners had 20 minutes for each text, and the instruction was to write a text about the picture.

- The purpose of the second text was to investigate to what extent the learners would include words they had met in the book. They were not reminded of the words, only encouraged to use any new words they had learnt in the book.

- Interview with the teachers based on the following questions:

- What did your pupils learn?

- In what ways do you think your pupils’ language skills developed?

- Which tasks did the pupils seem to like more or less?

- What would you do differently next time?

The field notes were written up after every lesson and the video recordings of pair and group work were transcribed; the interview with the teachers, which was carried out in English one week after the study ended, was audio-recorded and transcribed. Content analysis of all the data sets was conducted in two ways. The first was inductive, based on the following codes: P and NP for the positive and non-positive responses of the learners to the tasks; S, L, R, and W for the language skills (speaking, listening, reading and writing), V for vocabulary; and I for interaction patterns. The second was interpretive. The content was further analysed for any small but telling detail which might otherwise have been missed.

Procedures: tasks and interaction patterns

For five weeks, the English lessons, (three lessons of 40-50 minutes per week), were based on The Magic Finger. The book was divided into three sections, consisting of about 18 pages, which took just over a week to read. This division reflected the three parts of the story: the Gregg family turn into ducks; the family learn to live as ducks while the duck family takes over their home; the Greggs return to normal but have changed their attitude towards hunting. On each opening, either one whole page was taken up by an illustration, or there were two smaller illustrations on each page. Some pages contained as few as one or two sentences, and the longest stretch of text, 30 lines, consisted largely of dialogue, as does most of the book. The children listened to the teachers reading the book, in stages, and again in its entirety at the end. Sometimes the teachers would lead in to a lesson by re-reading a part of the story from the previous lesson. In some tasks, the learners first read the text and then had it in front of them as they listened; in others, they only listened. The tasks were designed by the researcher and the teachers, and are grouped into tasks for understanding the story and language-focused tasks. The list within each type is not exhaustive.

Tasks to support understanding

- Sequencing: The children were not informed in advance of the book they were going to work with. To arouse their curiosity and lead them to speculate, each learner in a group of four was given a picture from the first part of the book. They took turns to describe their picture to the group and had to agree on a sequence of events, in order to make sense of the illustrations.

- Jigsaw reading: In pairs, the learners were given an extract from the book, cut up into sections, and tried to reconstruct the text.

- Matching: Each pair of learners was given an enlarged picture from the book; the teacher read aloud, and as soon as the pairs thought their picture related to a specific part of the text, they stuck it on the whiteboard.

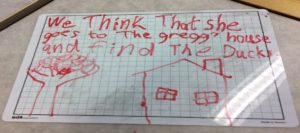

- Predicting: In pairs, the learners drew a picture and wrote a sentence to show what they thought might come next in the story. Figure 3 represents a girl’s drawing prompted by the question: What will she do next?

- Recapping: The teacher read out a number of statements about events which had happened so far and the learners decided individually if each one was true or false.

- Recapping: At the end of the book, each child wrote three statements about the events and characters: two had to be true and one was false. In groups of three, the children had to decide which statement was false.

Figure 3. Predicting events

Language-focused tasks:

- Bingo, based on words in the text.

- Categorizing words from the book according to what they had in common. For instance, words to do with houses, animals or numbers.

- Odd-one-out, where the learners, in pairs, had to decide which word was the odd-one-out in a given group of words.

- A crossword, completed in pairs.

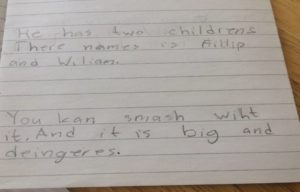

- Writing definitions for words, in pairs (Figure 4)

- Pass the Pencil, played in groups of four. As music played, the learners passed a pencil around the group. When the music stopped, the teacher read out a definition of a word. The learner holding the pencil when the music stopped wrote down the word for the definition, and the children helped each other choose what they thought was the correct word.

- Individually, the learners kept a vocabulary notebook and wrote words in sentences.

Figure 4. Definitions

Findings and Discussion

Insights into language learning

While some learners commented in the questionnaire on speaking, and others on writing more or better English, most stated they had learnt new words, adding in some cases, spelling or how to pronounce the words, and giving examples (deer and hunter were common).

Table 1 shows the results of all three tests for both classes (only results for the 23 students who completed all three tests are shown). The students are represented by letters, followed by their test results.

Table 1. Vocabulary test results

As can be seen in Table 1, in the pre-test, Class 2 had a higher average score (14), than Class 1, where the average was 11.5. Class 2 had a wider span of ability than Class 1: one pupil (K) was a bilingual speaker of English; two (I and J) were frequent gamers. The other learners in both classes played computer games in their spare time, but to a lesser extent. Frequent gaming has been found to have an effect on the lexical knowledge of young learners (Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2014), which might have a bearing on the high scores of two students in this case study.

In the post-test, the difference was smaller, with Class 1 averaging 16.9 and Class 2, 17.1. Though only the scores of those who completed all three tests are shown, all the learners in both classes made gains when the results of the pre-test are compared with the post- or delayed post-test. The delayed post-test showed little attrition and some children (D in Class 1, B and H in Class 2) even increased their score. This may have been because they failed to remember in the post-test words that they later remembered in the delayed post-test. It might also be that they encountered the words between the post-test and delayed post-test.

Regarding the texts which the learners wrote at the end of the study, there was evidence that the learners included words encountered during their reading of and interaction with the book; for instance, the use of the word duck in a second text when the L1 word had been used in the first. The influence of spoken English could be seen in the writing of the frequent gamers (birds are kinda annoying too, they tryna take our bread; Onech a pun a time ago there were 2 little ducks chillin on a stone they were best friends. The white duck sed dud I see so many people on the street).

In many cases, however, the second texts were no longer than the first, ranging in length from one or two sentences to almost a page of A4, with the average being half a page. Class 2, the more restless class, generally produced the shorter texts, which remained at less than half a page. Even though the children had been told at the outset that they were going to write the same text twice, they wondered why they had to write the second text, and were not motivated to do so. The teachers reminded them of the procedures and told them that we wanted to see what they could write after having worked with the book. With this encouragement, and prompted by their teacher, some tried to vary the task – if they had written a description before, they wrote a narrative, or a dialogue. It was also interesting to note that although the questionnaires and exit tickets were intended to be written in L1, many chose to write their exit ticket in English, with the number who did so increasing on each subsequent occasion.

During the study, there was no focus on grammatical structures. The learners’ texts are nevertheless useful in two respects. Firstly, they highlight the control of language features the learners had already encountered, for example, the inconsistent use of the third person ‘s’: The man have hair. He lives in a house. The same applies to the distinction between the simple (he swims) and continuous (he is swimming) aspects of the present tense, and the use of the auxiliary ‘is’ in the latter, which was sometimes left out. The texts displayed reasonable control of regular plurals, word order and articles (the/a/an), but control of capital letters and full stops was variable. Secondly, they revealed emergent features, which the learners had not yet worked with at school, such as the relative pronoun: Two duck sitting on the wall this names is Maya and Carl. In the following example, taken from a text written at the end of the study, the writer attempts to use the present perfect, formed in a similar way in Swedish, a subordinate clause and includes a new word, tiny: I can se that the ducks has swimd in the lake bikus it is tiny bubbles. A further example shows an attempt at the passive form: the family eats up of a fox.

With regard to strategies, the writing of the weaker learners demonstrates how they use Swedish to cover gaps in their English, as in this example from the writing of a very weak learner: The ducks ska tjuta (will shoot) the greege family för dom har tjutit (because they have shot) the ducks kids. A strategy for understanding chunks of text, which the more advanced learners applied in both listening and reading, was to identify key words or phrases. One pair of students were heard saying the phrase, late that night, when matching text with a picture showing the night. Meanwhile, those whose English was less developed attempted to understand every word, which slowed them down and prevented them from getting an overview of the events in the story.

Interaction patterns

Many of the tasks in the lessons were completed in pairs or groups. In general, Class 1 worked more harmoniously in groups, but for both classes, group work was more effective when each learner in the group had a specific role, in keeping with two principles of cooperative learning: individual accountability and collective responsibility. For example, groups of four worked well for picture sequencing, where each learner had their own picture, but less well for tasks which involved discussion or collaborative writing. Pairs, or groups of no more than three, where all the children could comfortably see the material in front of them, functioned better. This was particularly the case when the learners were reasonably matched in ability, where a more advanced learner supported a peer, and the personalities of the individuals facilitated cooperation. These findings are in line with those of Storch (2001), even though her research was conducted with adults.

The view of the teachers was that working together provided support for many learners, and they were used to pair and group interaction. However, this does not necessarily mean that all learners find it easy to cooperate. In Class 2 in particular, there were learners who preferred to work alone, or needed to do so, in order to concentrate. Furthermore, while some were able to work well with one other person, these learners found it harder to remain focused in a group. Although they reported enjoying group work, it could be because they were able to get away with doing less. In short, when creating conditions for learning, varying the interaction patterns is beneficial, as is the need for each individual to have a specific micro-task or role.

The learners’ reflective feedback

Based on the completed questionnaires and the exit tickets, it was found that most of the children enjoyed working with the book (11/13 in Class1 and 12/16 in Class 2). They particularly liked working in pairs and in groups, and the tasks based on pictures. They also mentioned liking the story, the humour and the happy ending.

In answer to the question, When you worked with the book, what did you like best? 8/13 students in Class 1 referred to the story. Some of their comments included: That the teacher got turned into a cat / It is fun! I like the ducks! / When the ducks hunted the Greggs / When they ate the apple / that a lot happened / Exciting, funny, fun – I’d like to have it again. In Class 2, only 4/16 learners referred to the story itself, with the majority focusing on tasks they liked best instead.

Learners across the two classes chose the following tasks as their favourites: creating a crossword in pairs and completing someone else’s crossword; and drawing a T-shirt. In the latter task, used at the end of the book, the learners were asked to draw the front of a T-shirt, and add three pieces of information about the book: a picture; a word and a number. For instance, this could be a pointing finger, the word magic and the number 2 to represent the girl’s two friends in the book, Philip and William. Many commented on the jigsaw tasks and the odd-one-out tasks as a puzzle or a challenge. For most, these activities were positive, but in the case of matching text and picture, one learner wrote, I did not like this because I got it wrong.

The learners’ responses regarding whether they would like to work with another book were rather ambiguous, as the majority chose Maybe. I subsequently asked the teachers to question their classes about this choice. On the one hand, the answers reflected mostly individual preferences: it would depend on the topic; individuals would like to read more or less themselves; some would like to listen more, others less, to the teacher. On the other hand, weaker learners found the text hard, despite extensive use of the illustrations in the tasks.

The teachers’ evaluation of the project

In the teachers’ view, most of the learners in their classes liked to listen to the book and they also learnt to listen better. Listening, along with speaking, is a key skill to develop in the young learner classroom. When children listen to a story, according to Cameron (2001), their focus is on meaning, on making sense of the story. This presupposes a story that children want to listen to, with characters and a plot that they care about. The learners’ references to incidents in the story, for example, the teacher turning into a cat, the ducks shooting at the family and the family attempting to eat apples when they only have wings, indicate ways in which the book left an impression, as do words such as fun and exciting, used to describe the book.

While graded readers and textbook material might present young learners with interesting stories, a piece of authentic fiction captures their imagination and provides a link to the curriculum for English in the Swedish education system. This includes the requirement that learners meet a diverse range of genres and formats from different parts of the English-speaking world. At the same time, if authentic fiction is used for language development, then there must be a focus on vocabulary and/or grammatical structures through different task types in order to support understanding and mediate learning. According to the teachers, tasks that made use of the pictures were popular with the learners and provided support for their learning. Drawing attention to the words used in the book through game-like tasks supported understanding and incidental acquisition. The Class 1 teacher also pointed out that the learners enjoyed coming up with their own ideas, which reflects Watkins’ (2018) observation of how stories provide a framework for personalizing language. Figure 5 shows two learners’ idea of what happens when the Greggs are transformed into ducks and the ducks take over their house:

Figure 5. Inferencing (I can’t writhe / They maby not find food / The ducks can steal there tings)

Despite attempts to support understanding, some of the more anxious, weaker learners reported being afraid that they would not understand the book. Following Krashen’s (1982) concept of the affective filter, that a learner’s emotional state can facilitate or inhibit learning, anxiety may have had a negative effect on their understanding. These learners might have benefited from more support by further adapting the tasks. For instance, when the learners had to rearrange pieces of text into a coherent whole, the weaker pairs could have worked with a shorter text, or been given the first and the last sentence to frame the text. In addition, the use of concept questions during the reading of the book would have provided extra support, and helped the learners realize that they did not need to know every word in order to understand.

Conclusion and future directions

The popularity of drawing was evident from the field notes, from the teachers’ interview and the questionnaires. A future project could investigate the use of the language learners’ drawings to process and remember the events of the story, as illustrated by the task in Figure 3. This task requires that the learner understands the story and can use that understanding to predict events. This involves both cognitive and linguistic demands. A further project could include tasks designed specifically to practise structures the learners have met in class, and over which the learners have some control, such as the two aspects of the present tense. Another project might include tasks designed to draw on or activate language structures, such as relative clauses, they may have learnt through other channels, and which they know how to express in L1.

Learners of all levels of proficiency could benefit from further writing activities, as a way to consolidate the language they know and to experiment with emerging language features. This would challenge those who possess a wider range of vocabulary, motivate reluctant writers, and support the weaker learners, allowing them to write what they can in English while using the L1 bridge for support. One example would be writing scripts for role play, which would also offer an opportunity to work more specifically with the spoken language as well as to build the self-confidence of those who struggle with writing.

Finally, while every part of the book was read by the teacher more than once we did not include interactive listening. Had we done so, the weaker learners would have had more support as they listened. This could have reduced their anxiety and thus removed a potential barrier to learning.

Although this was a small-scale project in terms of the number of participants, weeks and lessons, we can draw some tentative conclusions. One conclusion is that there are affective, linguistic and cognitive benefits from working with authentic literature in the young learner classroom. It is important to choose a text that appeals to all the learners in the class, which is a challenge in itself. Key ingredients are an engaging plot and characters with whom the learners will empathize, and, preferably, a theme which deals with real-world issues. The learners in this study cared about the fate of the ducks; most of them were of the view that hunting for fun is wrong; and they felt that the Greggs had learnt their lesson so that a happy ending was appropriate. Authentic texts which include ethical issues can give rise to discussion, and even though the learners may need to express themselves in L1, the teacher can take the opportunity to introduce new vocabulary in a meaningful way. A further point about the choice of text is it should provide the basis for constructing a range of language-development tasks, which will motivate the learners to think.

Regarding interaction patterns and task types, variety in individual, pair and group work is important, as some learners prefer to work alone, while others learn more effectively in collaboration. What is important in pair and group work is that each individual has a role to play. This has implications for task design, in ensuring that everyone is able to contribute, and that the task cannot be completed without their contribution.

The tasks in this study created an environment for learning as they intended to promote understanding and facilitate the acquisition of vocabulary. The results of the vocabulary tests show that the learners did acquire, and retain, many of the target words. This was also seen in the second text they wrote, in the notebook reflections and in the questionnaires. While many of these task types can be and are used in language teaching, my conclusion is that their cognitive and linguistic benefits are enhanced by the affective benefits of a class experiencing and exploring a work of authentic children’s fiction together.

Bibliography

Dahl, R. (2014). The Magic Finger, colour edition, illustrated by Quentin Blake. London: Penguin Random House UK.

References

Ahlquist, S. (2011). The Impact of the Storyline Approach on the Young Language Learner Classroom: A Case Study in Sweden. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Leicester, United Kingdom.

Birketveit, A., Rimmerheide, E., Bader, M. & Fisher, L. (2018). Extensive reading in primary school EFL. Acta Didactica, 12(2), 1-23

Bland, J. (2015). Oral storytelling in the Primary English Classroom. In J. Bland, (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12- year-olds. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 183-198.

Brewster, J., Ellis, G. & Girard, D. (2002). The Primary English Teacher’s Guide (2nd ed.). Harlow, Essex: Penguin

Brunsmeier, S. & Kolb, A. (2017). Picturebooks go digital – the potential of story apps for the primary EFL classroom. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 5(1), 1-20.

Cabrera, M.P. & Martinez, P.B. (2001). The effects of repetition, comprehension checks, and gestures, on primary school children in an EFL situation. ELT Journal, 55(3), 281-288.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational Strategies in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei. Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). The Psychology of the Language Learner Revisited. New York: Routledge.

Egan, K. & Judson, G. (2015). Imagination and the Engaged Learner: Cognitive Tools for the Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

Enever, J. (Ed.). (2011). Early Language Learning in Europe (ELLiE). London: British Council.

Fleta, T. & Forster, E.(2014).From Flat Stanley to Flat Cat: An intercultural, interlinguistic project. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2(1), 57-71.

Ghosn, I. K. (2013). Storybridge to Second Language Literacy: The Theory, Research and Practice of Teaching English with Children’s Literature. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Gray, J. (2016). ELT materials: claims, critiques and controversies. In G. Hall, (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of English Language Teaching. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 95-108.

Henry, A., Sundqvist, P. & Thorsen, C. (2019). Motivational Practice: Insights from the Classroom. Lund: Studentlitteratur, AB.

Kaminski, A. (2013). From reading pictures to understanding a story in the foreign language. Children’s Literature in English Language Education,1(1), 19-38.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

Lamb, M. (2017). The motivational dimension of language teaching. Language Teaching, 50(3), 301-346.

Lantolf, J. (2000). Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCafferty, S., Jacobs, G, & DaSilva Iddings, A.C. (2006). Cooperative Learning and Second Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

National Education Agency, (2011). Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Pre-school Class and School-age Educare (revised 2018).

Ohta, A. S. (1995). Applying sociocultural theory to an analysis of learner discourse: learner-learner collaborative interaction in the zone of proximal development. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 93-122.

Ong, W. (2002). Orality and Literacy. London: Routledge, pp. 199-217.

Pinter, A. (2017). Teaching Young Language Learners (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Storch, N. (2001). How collaborative is pair work? ESL tertiary students composing in pairs. Language Teaching Research, 5(1), 29-53.

Sundqvist, P. & Sylvén, L.K. (2014). Language-related computer use: focus on young L2 English learners in Sweden. ReCALL, 26(1), 3-20.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Watkins, P. (2018). Extensive reading for primary in ELT. Cambridge Papers in ELT Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from: https://www.cambridge.org/us/files/7915/7488/5311/CambridgePapersInELT_ExtReadingPrimary_2018_ONLINE.pdf