| Promoting Literary Reading in Lower Secondary English Language Classrooms

Sabine Binder & Liana Pirovino |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Reading literary texts in their original version presents notable challenges in the Swiss lower secondary English language classroom. Not only are students’ English language skills still developing, but teachers often lack methodological support. This article outlines a design-based research study aimed at addressing these issues. Two teaching sequences, based on existing theory and research in the fields of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and literary studies, were developed through close collaboration between a researcher and a practitioner. The teaching sequences were designed to facilitate students’ literary reading abilities, with the added benefit of providing support for teachers. The study analyzed students’ creative textual outcomes using qualitative content analysis to trace processes of literary comprehension. Findings showed that both interventions supported students in making interpretative inferences and empathizing with fictional characters’ emotions (signs of literary comprehension), and that they did so across the spectrum of students’ overall language proficiencies. In addition to demonstrating the feasibility and impact of the teaching sequences, the study offers valuable empirical insights into the process of literary reading in the English language classroom. Notably, the findings challenge the assumption that advanced language competence is a prerequisite for successful literary interpretation.

Keywords: cognitive processes, design-based research, literature and ELT, literary reading, lower secondary ELT

Sabine Binder is a lecturer and researcher in the Department of Foreign Languages at the Zurich University of Teacher Education (PHZH). She specializes in English literature and English language teaching methodology. Her research interests include contemporary global English literature, with a focus on making it accessible to English language learners.

Liana Pirovino is a researcher and mentor at the Zurich University of Teacher Education (PHZH), where she supports students in their teaching practice and works in various research projects. Her primary research interests lie in teacher professionalisation and the entanglement of theory and practice in teacher education.

Introductioni

Literary reading skills are a compulsory part of the Swiss curriculum for English language teaching (ELT) in lower secondary schools (ages 12–15 years). This is in accordance with ELT curricula beyond Switzerland and, notably, the Companion Volume to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (2018), reflecting an increased recognition of the role literature plays in language learning (Paran et al., 2021).

However, there is reason to believe that literature is not utilized to its full potential in lower secondary schools outside the academic, pre-university Gymnasium stream. Vocationally oriented lower secondary schools serve the majority of teenagers in Switzerland and are less likely to prioritize literary education. A survey conducted among 49 secondary school English teachers in the greater Zurich area revealed that over half do not regularly use literary texts, including multimodal texts, in their classrooms (Binder, 2021). Teachers reported that they would be more inclined to do so if they had access to more suitable texts, greater methodological support, and more time in class (Binder, 2021). While these findings are local, they mirror patterns observed internationally, where empirical research on literature use in lower secondary ELT remains scarce. Studies have revealed that teachers lack support in implementing literature, particularly when it comes to selecting suitable texts and employing student-centred, action-oriented teaching methods (Kräling et al., 2015; Lehrner-te Lindert, 2022). These challenges suggest that the literary education students receive may fall short of meeting curricular requirements.

Further insights come from Gardemann’s (2021) study of Hamburg lower secondary schools, which found that teachers’ use of literature largely depended on the coursebooks they used – which may offer more or less literary content. This overreliance on coursebooks is not unique to Germany. Calafato and Gudim (2022) report similar trends across many global contexts. In Switzerland too, coursebooks dominate instructional time. Even a cursory glance at English coursebooks commonly used in Swiss lower secondary schools reveals a striking absence of literary texts. This reflects trends observed in other countries, such as Japan, where literary materials have been systematically removed from junior high school textbooks in favour of factual texts deemed better suited for promoting communicative competence (Takashi, 2015).

Teachers may, of course, choose to incorporate literature beyond what the coursebooks offer. However, time constraints are a significant barrier. As one English teacher interviewed by the first author explains: ‘I think that’s one of the biggest issues we have. We need all the lessons to get through [the coursebook]; so where do I take the lessons for literature?’ (secondary school English teacher, personal communication, August 16, 2022). Concerns about time are not unique to Switzerland. Duncan and Paran (2018) also found that teachers at the upper-secondary level view literature as time-intensive, making it difficult to integrate it into a tightly packed curriculum. As a result, the dominance of coursebooks – especially those with limited literary content – leaves little room for literary study in practice.

Moreover, teachers’ perceptions of student ability play a significant role in determining whether literature is used. Gardemann (2021) found that the lower teachers rated their students’ language competence, the less likely they were to incorporate literature in their teaching. Cheung and Hennebry-Leung (2020) report a similar finding from Hong Kong, where a teacher’s perception of her students’ low proficiency constrained her use of literature. In Switzerland, this view is echoed in survey responses such as: ‘With C-level students [the lowest level], using fictional texts is very difficult’ (Binder, 2021). This combination of coursebook reliance and entrenched beliefs that lower-level students cannot comprehend literary texts in a second language can deprive these students of valuable literary experience and access (Hallet, 2009; see also Diehr & Surkamp, 2020; Mayer, 2022).

The current study sought to address these obstacles to integrating literature in the English language classroom on two levels. First, it developed a practical solution: a prototype design intervention (Euler, 2014; Bakker, 2018), consisting of two teaching sequences based on two short stories in their original English versions. The goal was to create conditions that facilitated literary reading. Secondly, the study aimed to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ cognitive processes when engaging in literary reading. To achieve this, a qualitative content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2022) was conducted on students’ written texts, mapping evidence of literary reading comprehension.

Theoretical Foundations of the Study

What exactly literary reading entails is not only contested, but culturally and historically determined. Rosenblatt’s notion of ‘aesthetic transaction’, rooted in reader-response theory, has long been influential in educational contexts (Hall, 2015, pp. 53–54). According to Rosenblatt (1986), meaning does not reside in the text alone, but ‘comes into being during the transaction’, that is, during a reciprocal process between reader and text (p. 123). The quality of this meaning-making process can fall anywhere on a continuum between what Rosenblatt terms ‘efferent’ and ‘aesthetic’ reading. Efferent reading refers to a text being processed on a factual level, with the aim of extracting objectifiable information that remains after the reading event. In contrast, aesthetic reading is highly individual and centres on the reader’s lived experience during reading, which may later be reflected on, evaluated or interpreted (Rosenblatt, 1986, p. 124). Crucially, aesthetic reading is not determined by a text’s inherent qualities, but by the reader’s stance or attitude toward the text (Rosenblatt, 1985, pp. 123–124). This means that even factual texts can be read aesthetically. In the context of this study, ‘literary reading’ will denote aesthetic reading of literary texts – thus specifying both the reader’s stance and the literary nature of the reading material.

Since inferencing – both literal and literary – plays a central role in discourse comprehension, it provides a valuable lens through which to assess students’ understanding of texts and will constitute a major focus of this study. Additionally, since aesthetic reading involves a personal engagement with the narrative, including the capacity to relate to characters and events, the second process examined is empathizing. Alter and Ratheiser (2019, pp. 381–382) describe empathic competence – defined as a reader’s ability to personally connect with characters – as ‘probably the first entry point into the discussion of a literary text’. Both inferencing and empathizing are therefore central components of competency models for developing literary skills in ELT at the lower secondary level (Alter & Ratheiser, 2019; Burwitz-Melzer, 2007; Diehr & Surkamp, 2015; Steininger, 2014). The following sections will examine these two processes in turn, beginning with inferencing and followed by empathizing.

Inferencing

Defined as ‘deriving logical conclusions from premises known or assumed to be true’, inferencing is ‘one of the most important processes necessary for successful comprehension during reading’ (O’Brien et al., 2015, p. i). According to Kintsch’s (1994) widely recognized construction-integration model, reading and comprehending a text means constructing a coherent mental model of the information that is presented in the text. Readers’ mental models evolve along three different levels of representation: ‘linguistic surface’, ‘textbase’ and ‘situation model’ (Kintsch, 1994, p. 39).

Figure 1. Enriched Model of Text Comprehension based on Kintsch (1994) and McCarthy et al. (2021).

The linguistic surface component entails activating lower-level processes, such as word recognition, syntactic parsing and word-to-word integration on a clause and paragraph level (Grabe & Stoller, 2020). The textbase component refers to forming a mental representation of the text, which Grabe and Stoller (2020) describe as ‘an internal summary of main ideas’ (p. 22). At this stage, inferencing begins to play an increasingly important role as readers interpret textual information situationally, for example, in relation to their background knowledge, feelings, text genre, or with a view to their reading goals, thereby creating an elaborated situation model (Kintsch, 1994, p. 41, 2019, p. 181). Readers make inferences that either bridge or connect ideas within a text (bridging inferences) or inferences that elaborate textual with extra-textual information (elaborative inferences) (McCarthy & Goldman, 2015, p. 586; McCarthy et al., 2021, p. 91). However, while elaborative inferences bring information from outside the text to fill in the blanks, ‘these inferences remain within the story world’ (McCarthy et al., 2021, p. 91). Reading so far remains on a literal level.

A literary interpretation occurs ‘when the reader generates inferences that connect information in the text with ideas about the world beyond the story’, so-called ‘higher-order inferences’ (McCarthy, 2015, p. 100). Literary reading that moves beyond the text can only be partially accounted for by existing models of (literal) reading. Kintsch (1994) claims that processing a literary text is not inherently different from processing a non-literary text, but that the creation of the three representational levels is potentially more complex (pp. 44–49). A reader needs to create and coordinate several complex, multilayered and potentially contradictory situation models in literary reading (p. 45, 49). Whether this more complex process is covered by the traditional situation model or whether it needs to be conceptualized as a distinct level of representation – visualized in Figure 1 as a ‘literary situation model’ – is contested (McCarthy et al., 2021, pp. 95–96).

Empathizing

In social psychology, empathy is considered a multidimensional phenomenon that includes both cognitive and emotional components (Davis, 1996). Cognitive empathy is the ability to understand what other people think and feel. Döring (2013, p. 297) compares cognitive empathy to taking somebody else’s perspective (see also Denham, 2024). Affective empathy, by contrast, is the ability to feel other people’s feelings indirectly. In this case, we synchronize our emotions with those of another person, especially if that person is close to us (Döring, 2013, p. 297).

In the context of literary reading comprehension, the focus is on the cognitive dimension of empathy. If readers are able to cognitively empathize with a fictional character, they are able to take that character’s perspective. Cognitive empathy is thus not only a sign of a reader’s active engagement with the text; as Matravers (2022) argues, empathy functions as ‘an epistemological tool for the reader’ (p. 146), helping the reader to understand the text. Literary situation models include spatial information, such as perspectival cues, allowing readers to construct the narrative world – their situation model – from the protagonist’s point of view (Matravers, 2022, p. 147). This study focuses on students’ cognitive empathy only with a fictional character’s emotions, where readers construct ‘a representation of the main protagonist’s emotional status’ (Gygax & Gillioz, 2015, p. 122).

To evaluate the impact of the two teaching sequences on students’ literary reading comprehension – focussing specifically on the processes of inferencing and empathizing – the analysis was guided by the following research questions:

- What evidence of literary reading comprehension can be identified in learners’ written texts?

- What dimensions of literary reading emerge from the data?

- How does this evidence relate to the two teaching sequences?

- How does this evidence correspond to students’ levels of language competence?

Two Teaching Sequences

Within close research-practice collaboration between the first author and a trained, native English-speaking teacher with thirty years of teaching experience in the USA and Switzerland, two teaching sequences were designed. Each teaching sequence revolved around a contemporary short story in its original form. Linguistic suitability for the target group was ensured and balanced with methodological considerations (Kirchhoff, 2019; see Appendix 1 for further information and vocabulary profiles of each short story). The teaching sequences spanned two to three lessons (of 45 minutes each, plus associated homework) and involved lead-in tasks, reading and post-tasks, which gradually progressed from literal to literary reading. Each task was introduced and framed by the teacher. The design of the teaching sequences was informed by Rosenblatt’s transactional theory of reading (1986) outlined above. At the same time, it was anchored in a cognitive-interactionist SLA framework, emphasizing rich input, cognitively and emotionally engaging materials and authentic, task-based interaction (Ellis et al., 2020; Loewen & Satō, 2017; Tomlinson, 2017).

Teaching sequence 1: ‘The Loner’

The first teaching sequence was based on ‘The Loner’, the opening chapter of British author Tommy Donbavand’s 2014 teen mystery novel Ward 13. Set in a hospital ward, it features a teenager named Mark who is alarmed by the mysterious disappearance of fellow patient Jack. While the mystery remains unsolved, clues hinting at foul play afford ample opportunity for inference-making on the part of the reader. The story is relatable and engaging to teenage readers because of the protagonist’s age and the story’s crime genre. It was thus expected to secure student motivation and response as a basis for literary engagement (Duff & Maley, 2007; Elliott-Johns, 2017; Kirchhoff, 2019; Weisshaar, 2015).

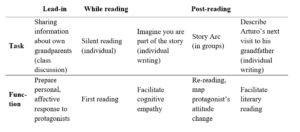

For the lead-in task, six pictures were used to elicit and pre-teach concepts and vocabulary to prepare students for reading. These included words pointing students to the crime genre (for example, ‘grave’), but also words that were assumed to be unknown to students (for example, ‘to squeak’ or ‘royal navy tattoo’). Students then read the story individually, and were allowed to use an online dictionary. After reading, they completed a ‘Mystery Story Map’ in random pairs (adapted from Heinz, 2017). This story map was a worksheet that prompted students to record information about the characters, places and mysteries in the text. Based on textual clues, they had to identify suspects and speculate about potential motives, prompting them towards adopting a literary stance. In a final class discussion students then shared their theories. Finally, they were instructed to ‘Write an ending to the story. Use your mystery map and your ideas (1–2 pages)’. This creative writing task built on and was prepared by the preceding group work. Kimes-Link’s (2013, pp. 375–377) empirical study emphasizes the importance of gradual, coherent progression of subtasks leading to students’ creative output in order to facilitate literary comprehension (see also Diehr & Surkamp, 2020, pp. 269–271; Kräling et al., 2015, p. 104; Rössler, 2020, pp. 278–279). An overview of the tasks can be seen in Table 1:

Table 1. Lead-in, reading and post-reading activities and their functions for teaching sequence 1.

Teaching sequence 2: ‘An Hour with Abuelo’

‘An Hour with Abuelo’ by Puerto Rican American author Judith Ortiz Cofer was first published in An Island Like You: Stories of the Barrio (1995). The story is about teenage protagonist Arturo’s one-hour visit to a nursing home, during which he gets to know his grandfather in new ways. Narrated in first person, the story ends with a feeling of unfinished business. What is open to interpretation is how Arturo is going to deal with the feeling of regret at having unexpectedly found and lost a conversational partner in his grandfather. Despite being the longer text, it is linguistically slightly more accessible than ‘The Loner’.

For the pre-teaching task students were asked to record information about their own grandparents for homework. Students then read the story individually, with access to an online dictionary, and completed two follow-up tasks. The first task asked them to imagine being part of the story, and to write about who they would be and why. This aimed at facilitating cognitive empathy with the characters. The second task was a group task called ‘Story Arc’ (adapted from Pfau & Vetterli-Verstraete, 2011), which required students to map the changes Arturo undergoes in the course of the story. As a final creative task, students were asked to write a piece describing Arturo’s next visit: ‘Imagine Arturo is going to visit his grandfather again. Describe his visit: Why does he go again? When? How does he feel about it this time? What questions does he ask his grandfather? What do they talk about? Write 6 to 8 sentences’. An overview of the tasks can be seen in Table 2:

Table 2: Lead-in, reading and post-reading activities and their functions for teaching sequence 2.

Method

Implementation of the teaching sequences

The teaching sequences were implemented in the same lower secondary class in the Canton of Zurich in March and May 2023 respectively. Prior to the implementation of the teaching sequence a C-Test was completed by all students in the class. C-Tests are a widely recognized and effective instrument to measure learners’ general language proficiency (Porsch & Wilden, 2017). They require learners to reconstruct meaning by completing missing word parts in a sequence of short texts (Grotjahn, 2002). The lessons were taught by the collaborating teacher (as the students’ regular English teacher). The first author acted as an observer and occasional teaching assistant. The class initially consisted of 24 students, numbered from 1_1 to 1_24. One student dropped out early, and another was absent for most of the implementation period and was therefore excluded from the study. The remaining 22 students were aged 12 to 13 years (grade 7 in Switzerland). Of these, 13 had a multilingual background.

Data analysis

The students’ creative texts were chosen as a unit of analysis. A total of 21 ‘story endings’ (SE) and 19 ‘next visit’ texts (NV) were analyzed. Evaluating students’ literary reading comprehension through their written texts constitutes an ‘off-line’ or ‘after-reading’ assessment (McCarthy et al., 2021, p. 92). A qualitative content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2022) was conducted by the authors. In line with the centrality of inferencing and empathy in literary reading, as outlined in the preceding theory chapter, two main codes were developed deductively: ‘Inference’, to capture higher-level processes of textual comprehension, and ‘Empathy (with emotions)’, to identify instances where learners empathized with a protagonist’s emotions. Using these two main codes, a first round of coding was conducted. During this process, a third main code, ‘Plot Twist’ emerged inductively. The units of coding in the first round were one or several sentences that formed an idea unit. In order to arrive at a more nuanced understanding of students’ inferences, a second round of coding of passages coded as ‘Inference’ was carried out, where the focus was put on single or multi-word items. All texts were coded with the MAXQDA programme. The three main codes and their subcodes are further explained as follows:

1 Inference. This code was used when the student made an inference based on the original short story (and developed it creatively). Given the crucial role of inferences in literary reading, this was used to capture higher-level processes of text comprehension. Three subcodes emerged inductively, but they are also supported by existing theory:

1.1 Repetition. This was used for verbatim repetitions of key words as they appear in the original short story. Levine and Horton (2015) state that a key word denotes a ‘salient detail’ that points to multiple layers of meaning (p. 126). Expert readers of literature recognize such words as pointers to levels of meaning that go beyond the literal meaning of a text. Consequently, they are used as a point of departure for literary reading (Levine & Horton, 2015, pp. 126–127).

1.2 Adaptation. This was used for words that do not appear in the short story and were used by students in an adaptive way. In other words, in a way that builds on the meaning of the original short story and goes beyond it.

1.3 Mix. This denotes the use of both verbatim original key words and adaptations.

2 Empathy (with emotions). This code was used when a student empathized with a protagonist’s emotions. Empathy with a fictional character’s emotions is considered a key part of literary reading and was therefore a main code. The subcodes denote which character the student empathized with:

2.1 Empathy for Mark. Used when a student empathized with Mark’s emotions.

2.2 Empathy for Jack. Used when a student empathized with Jack’s emotions.

2.3 Empathy for Young Arturo. Used when a student empathized with Arturo’s emotions.

2.4 Empathy for Abuelo. Used when a student empathized with Abuelo’s emotions.

3 Plot Twist. This code was used when the student created a sudden plot twist to bring the story to a positive end. This rather surprising phenomenon was observed only in the ‘story endings’ (SE). As ‘The Loner’ contains no clues suggesting a happy ending, this was given a separate main code. Two subcodes specify how the student chose to perform the plot twist.

3.1 Happy Ending. This was used when the student concluded their text with a sudden positive outcome.

3.2 Bad Dream. This was used when the students concluded their text with a sudden awakening from a bad dream to create a positive outcome.

Examples of how the codes were applied can be found in Appendix 2.

Findings

Main code ‘Inference’

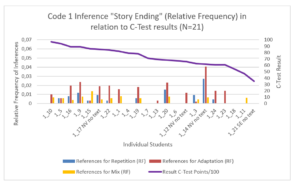

A total of 17 out of 21 ‘story endings’ (SE) contained inferences that students made based on the ‘The Loner’. The number of inferences made varied from 1 to 19. As Figure 2 illustrates, the subcode ‘Repetition’ was coded in 11 student texts, ‘Adaptation’ in 16 and ‘Mix’ in 13. Given that the creative texts vary in length considerably, not only within SE, but also between SE and ‘next visit’ texts (NV), relative frequency (number of inferences made divided by the number of words per text) was calculated in order to allow for comparison. The left y-axis depicts the number of references relative to the length (number of words) of students’ SE. Individual students’ results are presented according to their ranking in the C-Test, with scores ordered along the x-axis from highest to lowest scores. The right y-axis depicts C-Test scores (1–100).

Figure 2. Relative frequency of Inferences in SE texts.

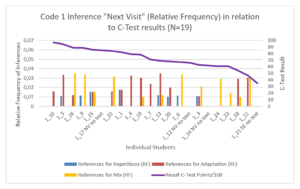

Figure 3 shows that a total of 18 out of 19 NV texts contained inferences that students made based on ‘An Hour with Abuelo’. Subcode ‘Repetition’ was coded in 8 student texts, ‘Adaptation’ in 14 and ‘Mix’ in 12. Again, relative frequencies are given, and the results are set against students’ scores in the C-Test.

Figure 3. Relative frequency of Inferences in NV texts.

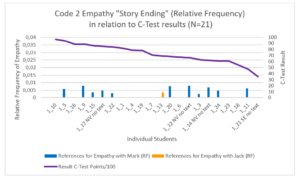

Main code ‘Empathy (with emotions)’

As Figure 4 illustrates, 12 out of 21 SE texts were coded for empathy with a protagonist’s emotions. Again, relative frequencies are given in the left y-axis, and the results are set against students’ scores in the C-Test (right y-axis). With one exception, the teenage protagonist Mark was the character empathized with. The adult protagonist Jack was empathized with only once. Altogether 9 SE contained no empathy.

Figure 4. Relative frequency of Empathy in SE texts.

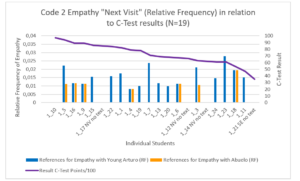

Figure 5. Relative frequency of Empathy in NV texts.

17 out of 19 NV texts were coded for empathy (Figure 5). While the young protagonist Arturo was empathized with in all the 17 texts coded for empathy, 7 texts empathized with Abuelo. No text empathized only with Abuelo, and 2 texts contained no empathy.

Main code ‘Plot Twist’

A total of 7 of 21 SE were coded for plot twist. Out of these, 4 were coded as ‘Happy Ending’ and 3 as ‘Bad Dream’. No comparable phenomenon was found in the NV texts. Evidence was found across the spectrum of C-Test results.

Discussion

Based on the findings presented, the following research questions will now be addressed:

- What evidence of literary reading comprehension can be identified in learners’ written texts?

- What dimensions of literary reading emerge from the data?

- How does this evidence relate to the two teaching sequences?

- How does this evidence correspond to students’ levels of language competence?

First, the two main dimensions of literary reading for which evidence was found, namely inferencing and empathy with a fictional character’s emotions, are discussed. Secondly, there is a discussion of how these dimensions related to the teaching sequences and to students’ levels of language competence.

Inferencing

Overall, a vast majority of learners’ texts contained inferences that pointed to literal and literary reading, that is, to processes of higher-level understanding of the short stories read in class. There were different processes of inferencing at work, as the data shows. In about half of the students’ texts, words were lifted verbatim from the stories (subcode 1.1 ‘Repetition’). In such instances, students embedded their repetitions into idea units that closely resembled the original stories, thus signalling literal understanding. What is more, by choosing to repeat key words from the story, students showed that they noticed them as salient pointers. McCarthy et al. (2021) state that ‘The knowledge of both what to look for and what it might mean are critical in the construction of interpretive inferences’ (p. 100). Students here displayed an awareness of ‘what to look for’. Even though they did not yet dive into ‘what it might mean’, they noticed the signposts and thereby signalled a literary stance.

A look at the next two subcodes reveals evidence of ‘what it might mean’. A vast majority of SE and NV contained adaptive words (subcode 1.2 ‘Adaptation’). For example, in student 1_18’s NV, adaptive word usage is printed in bold: ‘Arturo enjoyed this time with his grandfather immensely and wanted to visit him more often.’ This links back to textual clues found in ‘An Hour with Abuelo’:

I want to discuss this with him … I am about to ask him why he didn’t keep fighting to make his dream come true […] I walk slowly … toward the exit sign. I want my mother to have to wait a little. I don’t want her to think that I’m in a hurry or anything. (Ortiz Cofer, 1995, pp. 103–104)

Arturo’s engagement with the story of his grandfather’s life is expressed through his urge to ask questions and his ostentatious reluctance to leave the nursing home. The student projects this information into the next visit as Arturo’s immense enjoyment and his wish to visit his grandfather more. The student’s use of adaptive vocabulary shows them combining information from the story with their own creative transformations that move beyond the story. Examples like these are acts of literary reading and can be read as evidence for a literary situation model.

Students who wrote SEs for ‘The Loner’ often used adaptive words to continue the crime genre, picking up on Mark’s suspicions and his wish to know more. For example, student 1_19 wrote: ‘No clue survived. Not even the FBI or the police managed to figure it out’. The student’s adaptive vocabulary shows an intensification, even institutionalization (police/FBI), of Mark’s search for the truth. Students also used adaptive language to fill in gaps in the story with their own creative ideas, often imagining Jack’s disappearance as a murder. The original story reads ‘The bed was empty. Jack was gone’ (Donbavand, 2014, p.10). Student 1_24 wrote: ‘Most of ideas were scary and bad to think about, like that Jack was killed’, fleshing out and specifying what happened to Jack. Again, the use of adaptive language shows a move beyond the text, signalling literary reading.

Passages coded with the third subcode for inference (1.3 ‘Mix’), occurred at a similar frequency as those coded as 1.2, in both SE and NV. Subcode 1.3 was used for passages that contained both verbatim key words from the story and new words in an adaptive way, as seen in this example: ‘The doctors choosed persons who have no family and they took their organs out and bought these organs to rich people who needed organs’ (S 1_20). Not having any family is lifted verbatim from ‘The Loner’ (Donbavand, 2014, p. 7), while the hospital’s involvement in organ trafficking is the student’s own inference. Similarly to the examples coded as ‘Adaptation’, students were observed filling in the gaps of the story with their own creative ideas.

Examples from NV texts confirm similarities between ‘Mix’ and ‘Adaptation’. ‘What is your last wish bevor you have to go?’ student 1_11 has Arturo ask his grandfather. The use of ‘to go’ is lifted verbatim from the story and is understood correctly by the student as the grandfather not having long to live, whereas the words ‘last wish’ are adaptive, building on ideas in the text of the grandfather’s unfulfilled dreams of becoming a teacher and writer. In doing so, the student displays evidence of both literal and literary understanding. In conclusion, the evidence for subcodes ‘Adaptation’ and ‘Mix’ reveal many similarities. While ‘Mix’ was more immediately visibly anchored in the original story – through including verbatim repetitions – both phenomena can be taken as evidence for literary reading.

In contradiction to these generally high levels of literary reading, a substantial third of all students brought their SE to a positive end by using a plot twist. They did this by either creating a highly unlikely happy ending, for example, by having Mark save Jack from killer doctors without further ado (S 1_20), or by having Mark suddenly wake up, thus turning a dangerous situation into merely a bad dream. In doing so, these students disregarded not only crime genre conventions, but also the dark undercurrents in ‘The Loner’ and numerous textual clues hinting at foul play. At first glance, their text passages may be dismissed as evidence of incomplete text comprehension or wrong inferencing. A look at the full texts, however, confirms this only for student 1_7. All the other students began their SE by picking up on said textual clues in ‘The Loner’, demonstrating plausible inferencing. So why did they engineer this sudden turn? One reason may lie in the readers’ preferences. Given that ‘readers prefer positive outcomes for good characters’ (Gerrig, 2022, p. 311), these students might simply have wished to create a positive outcome for Jack, who is characterized as likeable and friendly. The second reason may be related to the age and emotional development of the students. As fascinated by the crime genre as the students were, at 12 and 13 years old they may not yet be capable or willing to process issues such as loss, death or violence, which might have interfered with their logical inferencing. Taking this into account, a plot twist may be viewed less as a sign of flawed literary comprehension, and more as a sign of creative preference or stage of emotional development. Implementing the teaching sequence with older students could serve to further test this hypothesis.

Empathy with a fictional character’s emotions

A majority of SE and NV contain evidence of cognitive empathy, which suggests a high degree of literary reading. Typical examples can be found in Appendix 1. However, a substantial minority (9 out of 21) SE contained no evidence for empathy, as opposed to only 2 in NV. Reasons for this discrepancy likely lie in the stories themselves. First, students may have more readily empathized with pleasant/attractive emotions rather than unpleasant/aversive ones. In ‘The Loner’, the protagonists’ emotions are more unpleasant than those experienced by Arturo and his grandfather. Moreover, both the SE and NV tasks required students to pick up from the emotions experienced by the characters towards the end of the story. While Mark initially has some pleasant feelings in ‘The Loner’, especially during his interactions with Jack, by the end of the story they are of a decidedly unpleasant nature. Young Arturo, on the other hand, grapples with very unpleasant feelings at the beginning of the story, but these, to his own surprise, turn into rather pleasant ones at the end. The findings hint at a well-researched phenomenon by cognitive psychologists: that readers update their mental representations of characters’ emotions while reading and that they seem to do so fairly automatically (Gygax & Gillioz, 2015, pp. 124–125). Secondly, many SE continued the narrative as crime stories, where a genre-typical focus on action may come at the cost of empathizing with characters’ emotions.

The subcodes reveal which characters are empathized with, and how often. In general, students mainly empathized with the young protagonists in both SE and NV. This finding may be due to narrative perspective and the age of the reader. Both short stories are focalized through the young protagonists, which likely helped students to empathize with these characters over others. Additionally, the students were a similar age to the protagonists, and similarity with characters is known to facilitate empathy (Gerrig, 2022, p. 312). While these findings are not surprising, they confirm the importance of teenage protagonists in facilitating the literary reading process. Still, in NV texts, there was substantial evidence of cognitive empathy with Abuelo, the elderly protagonist, evidence that is almost non-existent in SE. Again, reasons for this discrepancy likely lie in the stories themselves. The elderly Jack never actually makes an appearance in ‘The Loner’. While the reader learns much about him, they do so only from Mark, and in the end ‘Jack is gone’. Abuelo, on the other hand, is a key character in the story; his voice is present, making him easier to grasp and empathize with for students.

Overall, the study’s findings of cognitive empathy with characters’ emotions indicated that the nature of literary reading is strongly influenced not only by the reader’s knowledge, but by affordances of the literary text too (McCarthy et al., 2021, pp. 97–98). These two factors, together with a third one, namely the pre-reading and post-reading tasks, will be discussed in the next section.

How the dimensions of literary reading related to the teaching sequences

Despite congruent trends, there were differences in inferences and empathy between the SE and NV texts. Overall, more inferences and empathy were found in NV than in SE texts, which may be accounted for by differences in the teaching sequences. For one, the affordances of the short stories at the heart of each sequence differ. Linguistically, ‘The Loner’ was the slightly less accessible of the two texts and its portrayal of characters made it more challenging to empathize with them. Secondly, there were differences in the tasks that lead up to students writing their creative pieces. The lead-in task for ‘The Loner’ had a purely cognitive focus. It aimed at activating genre knowledge and pre-teaching challenging vocabulary, offering little room for an emotional response. By contrast, the second teaching sequence featured a preparatory task which facilitated a personal response on both a cognitive and an emotional level. Students were asked to record information about their grandparents for homework, which they did with great enthusiasm. Thus, before they even read the short story, their prior knowledge and positive feelings had been activated. In addition, a post-task for ‘An Hour with Abuelo’ asked students to take the perspective of a character, which facilitated empathy. Instructions for the final creative tasks also differed in their explicitness. SE was an open task, giving students more leeway as to the degree in which they displayed their literary understanding of ‘The Loner’. Instructions for NV included questions that guided students to think about specific aspects of Arturo’s next visit, such as Arturo’s reason for going, his feelings, and what questions he might ask. This placed an obligation on students to answer at least a few of the guiding questions, which they did, likely leading to increased evidence of empathy in their texts compared to SE texts.

This reveals a limitation of the study. The examined creative texts were constrained by the tasks and instructions, and therefore do not fully capture the range of students’ literal and literary reading comprehension. The study therefore only allows a selective assessment of students’ literary reading. It is important to note that a lack of inferences or evidence of empathy in either SE or NV does not necessarily equal a lack of literary comprehension.

Additionally, the effects of the affordances of the texts and tasks can only be observed in combination. They cannot be isolated. This limitation is an inherent consequence of the present study’s being situated in a design-based research paradigm.

How the dimensions of literary reading corresponded to language competence

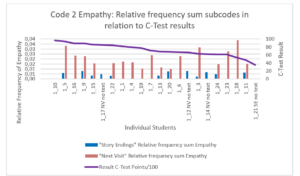

This study showed that evidence of literary reading, in the form of higher-level inferences and empathy, did not correspond to the student’s level of language competence. To show this, Figure 6 maps the relative frequencies of higher-level inferences made (sum of subcodes 1.2 ‘Adaptation’ and 1.3 ‘Mix’) against the students’ general language competence as established in the C-test. What becomes immediately noticeable for both SE (blue bars) and NV (orange bars) is that the level of inferencing did not correspond to the level of general language competence. While many linguistically less advanced learners produced high numbers of inferences, there are advanced learners who produced very few inferences. In fact, the highest scores were achieved by students who fell into the lower spectrum of language competence within the class (S 1_14 for SE and S 1_11 for NV). This phenomenon was more pronounced in NV texts. In NV texts, evidence for inferencing was not only higher, but more equally distributed, with high and low points situated across the whole linguistic spectrum. For SE there were more pronounced differences between the advanced half of the class, where more students displayed evidence for inferencing, and the less advanced half of the class, which showed great variance and featured both the lowest and the highest scores alongside a number of students without any inferences.

Figure 6. Sum of Subcodes 1.2 and 1.3 for SE and NV Texts.

Similarly, Figure 7 reveals evidence of empathy across the spectrum of language competence and between SE and NV.

Figure 7. Results sum Codes 2.1 and 2.2 for SE and sum Codes 2.3 and 2.4 for NV.

The findings indicate that the ability to experience empathy is independent of general language proficiency, as measured by the C-test, in both SE and NV texts. Even learners with lower C-test scores displayed a strong capacity for empathy. Notably, in NV, the top scorer (S 1_18) ranked at the lower end of the language proficiency scale. This suggests that learners were able to grasp the emotions of the story’s protagonists and adopt their perspectives effectively. These findings highlight the importance of selecting literary texts with emotional content that resonates with learners’ prior knowledge and experiences, as this alignment can enhance engagement in literary reading.

These are remarkable findings given that general language competence varied considerably within the class, with C-Test scores ranging from 35 to 97 out of 100 points. The qualitative analysis of this small sample indicates that literary reading and general language competence are separate competences. Expertise in one must not, as is often done, be equalled to expertise in the other. In sum, evidence of literary reading is related to affordances of the texts and the tasks, but not to students’ general language competence.

Conclusion

This study presented two design interventions that sought to address problems in implementing literary reading in English language classrooms. Qualitative evidence confirmed that both teaching sequences, which were developed in close collaboration between a researcher and an experienced teacher, were conducive to students’ literary reading. The students’ creative texts showed evidence of their ability to make inferences beyond the literal meaning of the short stories, as well as the ability to empathize with a protagonist’s emotions. Both indicate literary reading. Remarkably, this evidence emerged across the spectrum of students’ general language competences.

Besides demonstrating the feasibility and impact of the two teaching sequences within the present Swiss ELT context, the results yield insights into the relation between language and literary proficiencies, suggesting that these are distinct competences. Notably, advanced language proficiency did not emerge as a necessary prerequisite for successful engagement with literature in the present context. Therefore, the use of literary texts should not be made contingent on students reaching a particular level of language proficiency, as many teachers do, according to research by Gardemann (2021) and Cheung and Hennebry-Leung (2020). The present findings underscore the need to reconsider this practice.

In addition, while teachers’ concerns about time constraints are valid, curricular requirements to develop students’ literary reading skills at the lower secondary level – both in Switzerland and elsewhere – must still be met. When coursebooks fall short due to their limited literary content, as is the case in Switzerland and also noted by Takashi (2015) in Japan, this study offers a compelling rationale for periodically replacing them with literary texts supported by thoughtfully designed tasks. This approach promotes the gradual development of literary competence from an early stage, particularly when stories and tasks foster both cognitive and emotional engagement. Findings suggest that it was precisely the emotional connection linguistically less proficient students were able to establish that created a pathway into the literary text and facilitated their literary reading. Also, if literary competence is not entirely reliant on linguistic proficiency, there may be an opportunity for the transfer of literary skills acquired in other languages.

Hall (2015) notes that ‘the more expert reader [of literature] is likely to “enjoy” the experience more’ (p. 74), suggesting that teaching designs which effectively cultivate literary expertise may have the potential to spark reading enjoyment and motivation among learners at all language levels. This highlights a promising avenue for future research. In terms of assessment, the coding practices used in this study’s qualitative content analysis offer a useful approach for evaluating students’ creative responses to literature. Specifically, teachers might use vocabulary usage as a potential indicator of students’ depth of understanding, distinguishing between literal and literary comprehension. Additional implementations across varied contexts and the use of a broader range of evaluation methods are necessary to further validate these findings, refine the design of the teaching sequences and continue the iterative, design-based research process. Finally, the study underscores the considerable potential of collaboration between academia and teaching practice, a partnership that both sides have found beneficial. Expanding and institutionalizing these collaborations could further amplify their impact on learning outcomes.

Bibliography

Donbavand, Tommy (2014). Chapter 1: The Loner. In Ward 13 (pp. 5–10). Badger.

Ortiz Cofer, Judith (1995). An Hour with Abuelo. In An Island Like You: Stories of the Barrio (pp. 96–104). Scholastic.

References

Alter, G., & Ratheiser, U. (2019). A new model of literary competences and the revised CEFR descriptors. ELT Journal, 73(4), 337–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccz024

Bakker, A. (2018). Design research in education: A practical guide for early career researchers. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203701010

Binder, S. (2021). Literatur im Englischunterricht Sek I [Unpublished survey]. Department of Foreign Languages, Secondary School Education, Zurich University of Teacher Education.

Burwitz-Melzer, E. (2007). Ein Lesekompetenzmodell für den fremdsprachlichen Literaturunterricht. In L. Bredella, & W. Hallet (Eds.), Literaturunterricht, Kompetenzen und Bildung (pp. 127–157). Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

Calafato, R., & Gudim, F. (2022). Literature in contemporary foreign language school textbooks in Russia: Content, approaches, and readability. Language Teaching Research, 26(5), 826–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820917909

Cheung, A., & Hennebry-Leung, M. (2020). Exploring an ESL teacher’s beliefs and practices of teaching literary texts: A case study in Hong Kong. Language Teaching Research, 27(1), 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820933447

Cobb, T. (2023). VocabProfile (an adaptation of Heatley, A., Nation, I.S.P., & Coxhead, A. (2002). Range program) [Computer program]. Compleat Lexical Tutor. https://www.lextutor.ca/vp/eng/

Council of Europe (2018). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment: Companion volume with new descriptors. Council of Europe Publishing.

Davis, M. H. (1996). Empathy: A social psychological approach. Westview Press.

Denham, A. E. (2024). Empathy & Literature. Emotion Review 16(2), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/17540739241233601

Diehr, B., & Surkamp, C. (2015). Die Entwicklung literaturbezogener Kompetenzen in der Sekundarstufe I: Modellierung, Abschlussprofil und Evaluation. In W. Hallet, C. Surkamp, & U. Krämer (Eds.), Literaturkompetenzen Englisch: Modellierung – Curriculum – Unterrichtsbeispiele (pp. 21–40). Klett-Kallmeyer.

Diehr, B., & Surkamp, C. (2020). Methoden zur Entwicklung literaturbezogener Kompetenzen. In W. Hallet, F. G. Königs, & H. Martinez (Eds.), Handbuch Methoden im Fremdsprachenunterricht (1st ed., pp. 268–272). Klett-Kallmeyer.

Döring, N. (2013). Wie Medienpersonen Emotionen und Selbstkonzept der Mediennutzer beeinflussen: Empathie, sozialer Vergleich, parasoziale Beziehung und Identifikation. In W. Schweiger, & A. Fahr (Eds.), Handbuch Medienwirkungsforschung (pp. 295–310). Springer VS.

Duncan, S., & Paran, A. (2018). Negotiating the challenges of reading literature: Teachers reporting on their practice. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8 – 18 year olds (pp. 243–259). Bloomsbury.

Duff, A., & Maley, A. (2007). Literature. Oxford University Press.

Elliott-Johns, S. E. (2017). Literacy teacher education and the teaching of young adult literature: Perspectives on research and implications for practice. In J. A. Hayn, J. S. Kaplan, & K. R. Clemmons (Eds.), Teaching young adult literature today: Insights, considerations, and perspectives for the classroom teacher (2nd ed., pp. 27–45). Rowman & Littlefield.

Ellis, R., Skehan, P., Li, S., Shintani, N., & Lambert, C. (2020). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108643689

Euler, D. (2014). Design research: A paradigm under development. In D. Euler, & P. F. E. Sloane (Eds.), Design-based research (pp. 15–44). Franz Steiner Verlag.

Gardemann, C. (2021). Literarische Texte im Englischunterricht der Sekundarstufe I: Eine Mixed Methods-Studie mit Hamburger Englischlehrer*innen. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; J.B. Metzler.

Gerrig, R. J. (2022). Readers. In P. C. Hogan, B. J. Irish, & L. P. Hogan (Eds.), The Routledge companion to literature and emotion (pp. 305–316). Routledge.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2020). Teaching and researching reading. Routledge.

Grotjahn, R. (2002). Konstruktion und Einsatz von C-Tests: Ein Leitfaden für die Praxis. In R. Grotjahn (Ed.), Der C-Test. Theoretische Grundlagen und praktische Anwendungen (pp. 211–225). AKS-Verlag.

Gygax, P., & Gillioz, C. (2015). Emotion inferences during reading: Going beyond the tip of the iceberg. In E. J. O’Brien, A. E. Cook, & J. R. F. Lorch (Eds.), Inferences during reading (pp. 122–139). Cambridge University Press.

Hall, G. (2015). Literature in language education (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hallet, W. (2009). Literature and literacies: Literarische Bildung als Paradigma für Standardisierung, Differenz und Heterogenität. In C.-P. Buschkühle, L. Duncker, & V. Oswalt (Eds.), Bildung zwischen Standardisierung und Heterogenität: Ein interdisziplinärer Diskurs (pp. 53–80). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Heinz, S. (2017). The pizza mystery: Handlungsverlauf und Verdächtige eines Krimis in einer story map systematisieren. Der Fremdsprachliche Unterricht Englisch (145), 14–20.

Kimes-Link, A. (2013). Aufgaben, Methoden und Verstehensprozesse im englischen Literaturunterricht der gymnasialen Oberstufe: Eine qualitativ-empirische Studie. Narr Francke Attempto.

Kintsch, W. (1994). Kognitionspsychologische Modelle des Textverstehens: Literarische Texte. In K. Reusser, & M. Reusser-Weyeneth (Eds.), Verstehen: Psychologischer Prozess und didaktische Aufgabe (pp. 39–53). Hans Huber.

Kintsch, W. (2019). Revisiting the construction-integration model of text-comprehension and its implications for instruction. In D. E. Alvermann, N. J. Unrau, M. Sailors, & R. B. Ruddell (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of literacy (7th ed., pp. 178–203). Routledge.

Kirchhoff, P. (2019). Kanondiskussion und Textauswahl. In C. Lütge (Ed.), Grundthemen der Literaturwissenschaft: Literaturdidaktik (pp. 219–230). De Gruyter.

Kräling, K., Martín Fraile, K., & Caspari, D. (2015). Literarästhetisches Lernen mit komplexen Lernaufgaben fördern?! In L. Küster, C. Lütge, & K. Wieland (Eds.), Literarisch-ästhetisches Lernen im Fremdsprachenunterricht (pp. 91–107). Peter Lang.

Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung: Grundlagentexte Methoden (5th ed.). Beltz Juventa.

Lehrner-te Lindert, E. (2022). Schulische Vermittlung fremdsprachlicher Lesekompetenz im DaF-Unterricht der Sekundarstufe I. Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen, 51(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.24053/FLuL-2022-0003

Levine, S., & Horton, W. (2015). Helping high school students read like experts: Affective evaluation, salience, and literary interpretation. Cognition and Instruction, 33(2), 125–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2015.1029609

Loewen, S., & Satō, M. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge handbook of instructed second language acquisition. Routledge.

Matravers, D. (2022). Sympathy and empathy. In P. C. Hogan, B. J. Irish, & L. P. Hogan (Eds.), The Routledge companion to literature and emotion (pp. 144–154). Routledge.

Mayer, N. (2022). Zur Einführung in den Themenschwerpunkt: Jugendliteratur im Fremdsprachenunterricht der Sekundarstufe I für alle. Fremdsprachen Lehren Und Lernen, 51(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.24053/FLuL-2022-0001

McCarthy, K. S. (2015). Reading beyond the lines. Scientific Study of Literature, 5(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.5.1.05mcc

McCarthy, K. S., & Goldman, S. R. (2015). Comprehension of short stories: Effects of task instructions on literary interpretation. Discourse Processes, 52(7), 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.967610

McCarthy, K. S., Magliano, J. P., Levine, S. R., Elfenbein, A., & Horton, W. (2021). Constructing mental models in literary reading: The role of interpretive inferences. In D. Kuiken, & A. M. Jacobs (Eds.), Handbook of empirical literary studies (pp. 85–117). De Gruyter.

O’Brien, E. J., Cook, A. E., & Lorch, J. R. F. (Eds.). (2015). Inferences during reading. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107279186

Paran, A., Spöttl, C., Ratheiser, U., & Eberharter, K. (2021). Measuring literary competences in SLA. In P. Winke, & T. Brunfaut (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and language testing (pp. 326–337). Routledge.

Pfau, A., & Vetterli-Verstraete, M. (2011). Littura: Ideen zum Literaturunterricht. Lehrmittelverlag Zürich.

Porsch, R., & Wilden, E. (2017). The development of a curriculum-based C-test for young EFL Learners. In J. Enever & E. Lindgren (Eds.), Early language learning: Complexity and mixed methods (1st ed., pp. 289–304). Channel View Publications.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1986). The aesthetic transaction. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 20(4), 122–128. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3332615

Rössler, A. (2020). Verfahren der Erschliessung narrativer fiktionaler Texte. In W. Hallet, F. G. Königs, & H. Martinez (Eds.), Handbuch Methoden im Fremdsprachenunterricht (1st ed., pp. 276–280). Klett-Kallmeyer.

Steininger, I. (2014). Modellierung literarischer Kompetenz: Eine qualitative Studie im Fremdsprachenunterricht der Sekundarstufe I. Narr Francke Attempto.

Takashi, K. (2015). Literary texts as authentic materials for language learning: The current situation in Japan. In M. Teranishi, Y. Saito, & K. Wales (Eds.), Literature and language learning in the EFL classroom (pp. 26–40), Palgrave Macmillan.

Tomlinson, B. (Ed.). (2017). SLA research and materials development for language learning. Routledge.

Weisshaar, H. (2015). Kriterien der Textauswahl. In W. Hallet, C. Surkamp, & U. Krämer (Eds.), Literaturkompetenzen Englisch: Modellierung – Curriculum – Unterrichtsbeispiele (pp. 91–99). Klett-Kallmeyer.

i This article is based on research funded by the PHZH Research Foundation, whose support is gratefully acknowledged. We also wish to express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, and to the language teacher, whose contributions greatly enriched the project and without whom this work would not have been possible.

Please download the PDF of the article to access the Appendix.