| Young Adult, Classics and Fiction for Adults: What First-Year Student Teachers of English Choose to Read

Melissa Kennedy |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Research about motivating children and youth to read, both for leisure and in school contexts, often promotes YA and children’s books, graphic novels, and multimodal literature. Such texts are well-suited to competence-based curricula, to both L1 and ELT education, and the wide range of material that offers school students choice and reading autonomy. YA literature and its pedagogy are, however, often assumed to be quite different from the use of classics in the classroom. Classics have been pejoratively associated with compulsory curricula or teacher choice, difficult and outdated content, and traditional analytical-critical methodologies that negatively impact young people’s attitudes towards literature and reading (Beck, 1995; Bushman, 1997; Duncan & Paran, 2018; Spann & Wagner, 2022; Thompson & McIlnay, 2019; Wexler, 2019). These assumptions, however, are challenged by the findings of a study of 285 first-year Bachelor of Education student teachers in Linz, Austria, who each chose one novel to study in their introduction to fiction seminar. The results show a clear preference for fiction marketed for adult readers amongst student teachers, followed by literary classics as both more popular than YA fiction. Student teachers’ self-evaluated attitudes and opinions show no differentiation of motivation, enjoyment, or satisfaction across the three types of literature. This article thus argues for a more inclusive understanding of young people’s motivations for reading that may include the pleasure of a difficult text and genre interests that expand the definition of YA readers and the YA genre.

Keywords: classics, genre fiction, literature in ELT, teacher training, YA fiction

Melissa Kennedy is Professor of English Literature and Cultural Studies at the University of Education Upper Austria in Linz, and Privatdozentin at the University of Vienna. Recent work includes chapters in educational handbooks The Anglophone Novel in the 21st Century (WVT, 2023) and Introducing Economic Criticism: Methods for Analysing Literature, Culture, and the Economy (Palgrave, forthcoming).

Introduction

Young Adult (YA) fiction, children’s literature, picturebooks, graphic novels, and multimodal literature are widely thought to promote children’s and young adults’ motivation to read, drawing on intrinsic motivation to encourage a love of reading that may create avid and life-long readers (Cremin et al., 2014; Cremin, 2020; Day & Bamford, 1998; Deci et al., 2001; Eisenmann & Summer, 2020; Krashen, 2011; Lewis & Dockter, 2011; Nilsen et al., 2012). They are often espoused for educational contexts in both L1 (Davison & Daly, 2020; Knickerbocker & Rycik, 2020; Wolf et al., 2011), and ELT classrooms (Bland, 2013, 2018; Delanoy et al., 2015), as such literature is well-suited to extensive reading and competence-based curriculum aspects, supporting media literacy, critical thinking, interculturality, global awareness, and recognition of diversity (Delanoy et al., 2015; Fazzi, 2023; Grimm et al., 2015; Kramsch, 1998).

Changes in ELT curriculum development also promote the use of literature in the classroom. Rectifying a gap in the first iteration of the Common European Frame of Reference (Council of Europe, 2001), the 2018 Companion update added three new reading scales focused on literature: reading as a leisure activity, expressing a personal response to creative texts, and analysis and criticism of creative texts. The three new scales offer a balance between different literary theories and practices, incorporating more recent research on the importance of fostering reading for pleasure and the role of school in creating avid and life-long readers (Cremin, 2020; Krashen, 2011), alongside the more established reader-response theory, (Nünning & Surkamp, 2006; Rosenblatt, 1994; Tomlinson, 1998) and older forms of traditional literary analysis and critique. Based on the CEFR, the new 2023 Austrian school curriculum for lower secondary has tempered its exam-oriented approach in favour of a ‘more active, multi-sensory, creative approach to language learning’ (BMBWF, 2023, p. 1), which includes creative and playful elements through songs, poems, comics, short literary texts, film clips and short videos (BMBWF, 2023, p. 1–2). The Austrian curriculum changes respond to an observed shrinking of literature in secondary and tertiary education since the advent of standardized formal testing and increasing dependence on ELT coursebooks (Bloemert et al., 2017; Grimm et al., 2015), along with integration of digital and media literacy, which are now built into national education.

The need for ELT teacher education in literature in order to fulfil the CEFR’s and new curriculum’s aims is here apparent. Certainly, in the German-speaking ELT context, many scholars have long advocated for use of literature in the classroom along the lines of that belatedly outlined in the CEFR (see, for instance, Delanoy et al., 2015; Nünning & Surkamp, 2006; Reichl, 2009; Thaler, 2008; Grimm et al., 2015; Volkmann, 2016). In arguing for a more expansive, inclusive approach to literature in the language classroom, however, such work registers the ongoing legacy of what Laurenz Volkmann calls the ‘philological paradigms’ of canonical texts and critical interpretation (Volkmann, 2016, p. 194). These continue to cast their shadow on current student experience and teacher classroom praxis, no doubt influenced by the critical-analytical method still dominant in most university English departments where future teachers receive their literary education.

Registering the dominance of the British and American literary canon in German ELT, several studies have collected data from first-year tertiary BA students on the English-language literature they had been exposed to in their high school ELT classes (Beck, 1995; Kirchhoff, 2016, 2019; Nünning, 1997; Schreyer, 1978). These studies, which span student cohorts from 1976 (Schreyer) to 2014 (Kirchhoff) show remarkable homogeneity of a very narrow canon of British and American plays, novels, and short stories that continue to circulate at secondary schools. In both Schreyer’s and Beck’s studies, Shakespeare, Orwell and Hemingway accounted for over 35 per cent of all authors and texts, leading Beck to title his paper, ‘Macbeth, Animal Farm und kein Ende!’ At a similar time, Nünning’s (1997) top-ten list also features all the same novels listed by the previous authors, including the mid-twentieth-century dystopian trio of Orwell, Huxley and Golding, along with Salinger, Steinbeck and Fitzgerald. By the time of Petra Kirchhoff’s 2009-2014 data set, the same most-listed writers and works as in the previous studies appear, with only two post-1950s novels, Nick Hornby’s About A Boy and T. C. Boyle’s The Tortilla Curtain, and no female writers. Notably absent from these most-read lists, as Kirchhoff points out, is awareness of postcolonialism, gender studies, and the cultural turn to other media forms. She does, however, note a weakening of this very particular canon, as these classics represent only 36 per cent of the total list of texts read in her study, compared to 78 per cent in Nünning’s (Kirchhoff, 2016). Nonetheless, the particular subset of canonical literature that continues to circulate in over 40 years of surveys suggests a tendency for each generation of new teachers to work with those same texts in the German-speaking educational realm.

The import of YA literature into more recent ELT classrooms is, perhaps surprisingly, not clearly corroborated in these studies. According to Kirchhoff, the relatively low proportion of YA literature in her survey, at 26 per cent, suggests the ongoing classroom practice of only introducing authentic literary texts at upper-secondary levels (Kirchhoff, 2019), which is only attended by about 10 per cent of school pupils. Following up on the implication that only a minority of school pupils are exposed to English literature at all, Harald Spann and Thomas Wagner’s 2016-2019 Austrian study of first-year B.Ed. student teachers of English found that coursebook-dominated classrooms and standardized testing negatively impacted on exposure to other literature (Spann & Wagner, 2022). For these students, the overwhelming majority of exposure to literary texts at school came solely from the coursebook, which included songs, poems, short stories, comics and novels. At lower-secondary level only 30 per cent were exposed to poems, comics, stories or plays outside of the coursebook, which corroborates Kirchhoff’s findings in Germany that literature tends to be reserved for the elective upper-secondary school. Spann and Wagner’s results further show that only 40 per cent of students in upper secondary worked with any form of literature, although this corpus comprises 69 per cent of young adult literature (Spann & Wagner, 2022). Their results show that literature in the ELT classroom is uneven and mixed, with the majority of school pupils finishing school without any contact with literature in ELT. All the above studies suggest that fulfilling the CEFR’s and new curriculum’s aims will require significantly new approaches to literature and media in tertiary teacher education and continued education workshops for in-service teachers to address these gaps.

It is within these parameters that teachers of literature at the University of Education of Upper Austria (PHOÖ) have developed an approach to literature that integrates the CEFR scales ‘reading for leisure’ and ‘personal responses to literary texts’ along with the more traditionalist ‘analysis and criticism’ scale. The ABC Approach aims to model and develop methods for operationalizing the three CEFR scales by incorporating (A)nalysis, (B)ook response, and (C)reativity into all ELT class work, based on student choice and an understanding of literature to include all narrative modes of text and media. Within this framework, first-year students in the introduction to literature seminar have been asked to each choose one novel to work with for the semester. The quantitative and qualitative results from end of semester student questionnaires are presented in this paper. This data adds to and expands the earlier German and Austrian studies to offer an updated snapshot of student literary knowledge, experience, expectations and preferences. Building on the earlier studies’ focus on what students have already read at school, this study asks students to choose what they want to read at university. Whereas the earlier studies do not record whether the school booklist was chosen by the school students or teachers, the ABC Approach is based on choice autonomy, within which student teachers’ school experiences, alongside personal interests and motivations, may have shaped their expectations of appropriate literature for ELT education. The findings are local and specific to Austrian high school experiences and ensuing attitudes about studying English literature. They are also specific to first-year B.Ed. student teachers at a specialized teachers’ college, rather than a mixed cohort of university B.A. and B.Ed students. This paper’s mapping of student teachers’ reasons for their choice gives insight into what literature students are interested in reading in an educational context geared towards future ELT teaching. Responses about both their enjoyment of their book and their satisfaction with their novel further reveal attributes of positive book experience in the tertiary setting. As preliminary analysis from the ABC Approach data corpus, this study contributes insight into teacher education methods that foster positive approaches to literature that are transferable to these future teachers’ own classrooms.

The Study

The present data set is drawn from the 285 first-year students who began their studies in the years 2020 to 2023 in the Cluster Mitte Linz site in Austria, for whom this obligatory course was their first experience with literature at university. All students had graduated from Austrian secondary schools (High School or Vocational School), and there were no English native speakers. This paper presents quantitative data on these students’ book choices and qualitative data on their satisfaction with their book choice. Choosing their own novel to work with for the course offers a degree of student autonomy and confidence as ‘expert’ of their own text, thus shifting the teacher to a supporting role rather than holder of knowledge and key to interpretation (Blau, 2003; Reichl, 2009; Showalter, 2003). Working with a text they have chosen helps student teachers privilege their reader response and encourages their creativity, which are pillars of the ABC Approach that are easily suppressed by traditional analytical methodology focused on unlocking assumed hidden meanings. These methods were consciously chosen in an effort to move away from the canon-centred, teacher-led expectations of literary study that students may have developed from their own school experiences and conceptions of their future role as English teachers. The choice criteria outlined in the course description reads as follows:

You can choose any novel or graphic fiction written in English of at least 150 pages long. It can be your favourite novel or something you’ve read before, but no Harry Potter. Any genre is fine, including YA, romance, historical, science fiction, fantasy, or classics. Postmodern literature and books within series are not recommended. Non-readers can discuss with their teacher the possibility of studying a narrative computer game.

Data for this study come from an end-of-semester questionnaire across six semesters from 2020 to 2023. The results come from 16 class groups, each of maximum 20 students, taught by two teachers, including online during COVID. Due to the limits of the Moodle educational platform, the responses were not anonymous. The full set of questions is available in the appendix, though this paper only analyses a subset of these. As a long-term rather than a one-off study, the data are affected by some differences of book selection criteria and the parameters of the feedback questionnaire. Over the three years of the current data set, there was some variation in the guidelines for choosing a novel. One year, students were allowed to choose a book in pairs.[i] One teacher sometimes added the choice criterion that either the author or text had to have won a literary prize, and the option of YA fiction was only added in the second year of the study. After a glut of Pride and Prejudice, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and The Great Gatsby, these books were later discouraged, mostly due to the teachers’ suspicion of copying between students and due to the ease of researching famous works online. There is also a distinct possibility that students from previous semesters recommended or lent their books and notes to others, further skewing the choice. In the last semester represented in this data set, the advent of ChatGPT led the teachers to drop the main assessment item of full end-of-term analytical essays in favour of portfolio-style assessment items of literary analysis, reader-response, and creative outputs. This change perhaps makes the need for a banned book list obsolete, as it reduces the temptation to copy ideas and essays. Across the survey period, there were also some changes to the questionnaire, which was only run by myself. This accounts for the lower number of responses to the qualitative questions than the quantitative data on book choices.

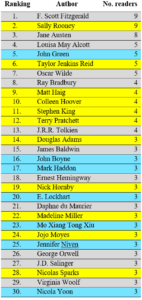

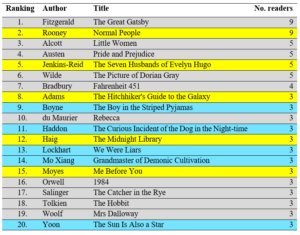

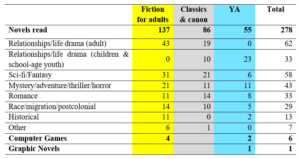

This paper follows the earlier German studies in presenting results on the most-read authors (Table 1) and the most-read novel titles (Table 2) in order to gain an overview of student choice. These ranking lists arranged by number of readers adopt Schreyer’s and Beck’s method. This form of data representation makes visible similarities and changes in first-year English majors’ reading knowledge and practices, and thus allows for comparison with the data about novels from the earlier studies. In order to form a deeper understanding of what types of literature students chose to read for this class, the 203 individual novels were each categorized as YA, classics and canon, or fiction for adults. Outside of the YA definition of books suited to 12- to 18-year-olds, this study did not use the category of New Adult, often defined as books suited for 18- to 25-year-olds: these books were categorized as for adults. The criteria for considering a novel a classic or canonical was a literary text often studied at school and university published before the 1980s, which includes James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Sylvia Plath. By contrast, later-published, high-brow literary texts were classified as fiction for adults. In Table 3, these three categories were further broken down into each novel’s generic and content features. Together, these tabulations attempt to offer a more nuanced picture of student-teacher choice.

These three quantitative tables are set alongside two qualitative questions, ‘Would you have read this novel if it weren’t for this course?,’ and ‘Are you satisfied with your choice for the purposes of this class?’. These reveal interaction between students’ preconceptions of what makes an appropriate novel to study in an educational context alongside feelings of reading pleasure in both their choice motivation and their satisfaction with their choice. The responses to the qualitative questions were coded for keywords using Maxqda Analytics Pro 2020 software. For the purposes of this short paper, however, I present only overall trends from the coding rather than statistical breakdown of the data.

Results

Quantitative data on the most-read authors and titles

The Linz cohort of 285 student teachers chose a range of 164 different authors and 203 different literary works. The tables below present the top-ranked authors (Table 1) and top-ranked novels (Table 2), listing only those read by three or more students, followed by the frequency of genre features (Table 3). The lines in the tables are colour-coded by the three categories of YA (blue), canon and classics (grey), and fiction for adults (yellow). Table 1 and Table 2 offer a snapshot of the range of work chosen by students, although this does not represent the majority of authors and texts, as 66 per cent of students were the sole reader of their chosen author. Table 3 presents a breakdown by genre of all 203 individual novels read, offering some insight into student interests by content rather than by expected level of difficulty or age suitability.

Table 1. The most-read authors.

Broken down by novel type, there are 12 canonical writers (grey), read by 53 students, 11 writers of fiction for adults (yellow), read by 44 students, and seven YA writers (blue), read by 23 students.

Table 2. The most-read novels.

In Table 2, ten of the top 20 novels are classics, with a total of 43 readers. Both YA and fiction for adults each have five top 20 texts, with more readers of fiction for adults (23) than of YA (15).

While the range of authors and texts in this study are far more diverse and more contemporary than in the earlier studies on what students have read in school, the same authors and titles do reoccur. The mid-20th-century male canon is still very much present, with Orwell, Salinger, Bradbury and Hemingway on the above most-read lists, while Huxley, Golding, and Steinbeck also each had two readers in the Linz study. These findings suggest the cultural capital of these texts and authors continue to circulate in English education in the German-speaking world. Equally as interesting are the classics that have moved up in popularity. Fitzgerald and Wilde, who only appear in the top 20 of Schreyer’s and Beck’s studies, along with 19th-century women’s writing by Austen and Alcott, who did not appear at all on the earlier German-school English reading lists, were so popular in the first year of the Linz study that they were later strongly discouraged. As discussed below, such texts and authors correspond with recent popular films and series that have introduced a new generation to these classical texts.

Table 3. Total number of readers by genre and contents features.

The breakdown by genre and content in Table 3 helps collapse expected differences between the categories. The three quantitative tables offer a complex picture of students’ choice that muddy assumptions both of the popularity of YA and antipathy towards classics. The study shows that in an educational context, these first-year student teachers choose to read a novel for adults (49 per cent) or a classic (31 per cent) over and above YA fiction (20 per cent). Even accounting for the fact that YA literature was only allowed from the second year of the three-year study, student choice of this genre is perhaps lower than expected, given that first-year students might be considered themselves at the top of the YA age range, that reading in a foreign language may make text complexity a consideration, and with their future role as ELT teachers in mind.

The significant presence of classics and canonical texts suggests student-perpetuated value judgements of appropriate literature to study, and does not show an aversion to difficult texts. The question ‘How many novels do you read per year in English?’ found that 50 per cent claim to read 1-5 novels a year and a further 25 per cent read 6-10. At either end of the spectrum, a similar number claimed to be non-readers (16 responses of 0 books) as avid readers (19 responses of 15+ books). The 31 per cent of readers of classics for class is thus significantly higher than the numbers of self-avowed avid readers in English, suggesting a number of students who were nonetheless confident enough to tackle a difficult book. Similarly, although 16 students self-identified as reading zero novels a year, most of them still chose to read a novel for class rather than a manga or a computer game, with only seven students taking up the opportunity to work with graphic fiction or a narrative computer game.

While the data about genres will be analyzed in the discussion section below, some smaller points about publication date, author’s gender, ethnicity and nationality also contribute to the earlier studies of German ELT students’ knowledge of and interests in Anglophone literature and culture. 25 per cent of the novels were published between 2017 and 2021, a maximum of two years before the book was chosen by students, and nearly 50 per cent were published in the ten years before. Of the classics and canonical texts, under half were nineteenth-century texts, with twentieth-century literature evenly split between British and American authors. In terms of writer’s gender, the Linz study reports an almost even split, of 81 female and 83 male writers. This demonstrates a clear shift in gender representation from the earlier Schreyer study of canonical literature, which featured only one female writer (Virginia Woolf) among his top 22 most-cited authors, a feature repeated in the top ten of Kirchhoff’s 2009-2014 study and only slightly improved in Beck’s 1995 study of 57 writers that included five women. By contrast, many of the classics chosen by Linz students were by female writers, including Louisa May Alcott, Jane Austen, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, Elizabeth Gaskell, Zora Neale Hurston, Harper Lee, Sylvia Plath, and Mary Shelley. This stark difference may reflect changing ways of accessing classical texts, from 20th-century set reading lists and graded readers to social-media book discussions and media crossover of the digital age, offering the predominantly female student population ready access to a female writing tradition that was all but absent in German ELT education.

In terms of race, ethnicity and nationality, however, the Linz cohort shows only a slightly wider range than in the earlier German studies, corroborating Kirchhoff’s claim that postcolonialism seems to have passed Germany by. Schreyer’s list solely consists of white British and American writers, while Beck lists four white writers from Ireland and Canada. In both these earlier studies, British writers outnumber American by about two to one. By 2020s Linz, this trend has inverted to 87 American authors and 56 British. A further six of the 164 writers are from Anglophone nations (Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Margaret Atwood, David Malouf, Yann Martel, Alan Paton, and Abdulrazak Gurnah). In terms of ethnicity, the writing profession represented remains overwhelmingly white. The Linz study includes seven Black American writers (Baldwin, Bennett, Hurston, Morrison, Thomas, Walker, Whitehead) and two Black British authors (Blackman, Wheatle), one US-Indian (Doshi), Latinx (Cummins), and US-Afghani (Hosseini). Although writing in translation was not encouraged, along with the recently published Chinese writer Mo Xiang Tong Xiu, one student each also chose classics by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Gabriel García Márquez, and Haruki Murakami, along with a manga by Tsugumi Ohma.

Notably missing from Tables 1 and 2 are the kind of recently published, high-brow literary fiction novels likely to be chosen by lecturers for Anglophone university reading lists but far less popular than earlier canonical writers and classics when chosen by students. Only Madeline Miller might fit this description, whose retellings of Greek myths, The Song of Achilles and Circe, are sophisticated forms of writing back to the canon. Some literary writers and fiction do appear among the whole cohort, notably Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Anna Burns’s Milkman, and Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day (each two readers), and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus, Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, Abdulrazak Gurnah’s By the Sea, Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, Yann Martel’s The Life of Pi, Ruth Ozeki’s The Book of Form and Emptiness, Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, and Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, each read by only one person. Students’ knowledge of these kinds of texts suggests some familiarity with the English-language literary reviewing and prize industry, researched and sought out by students looking for famous books or writers, with similar motivation as those students who read classics.

Qualitative data on choice criteria and satisfaction with the book

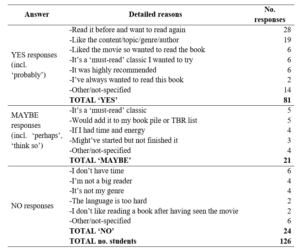

The second set of data pertains to qualitative information on choice of text, as a means of evaluating the importance of choice on motivation and reading pleasure in an educational setting. Table 4, from the question ‘Would you have read this book if it weren’t for the class?’, aims to uncover whether students enjoyed their books enough to classify them as suitable reading for pleasure, outside of the educational context. Table 5 reports on the question ‘Were you satisfied with your book choice for the purposes of this class?’ Students answered this question in ways that showed their preconceptions about what a literary class would require, along with many self-evaluations of their sense of achievement of the course expectations.

Table 4. ‘Would you have read this book if it weren’t for the class?’

64 per cent of students who answered this question claim they would have read their book for leisure, while under 20 per cent admitted they would not. The majority of comments cluster around emotive expressions of preference: they ‘wanted’ to read or reread it, ‘liked’ the movie, the author, the genre or topic, or had heard good things about it, including reviews and recommendations (102 responses). The single most common choice criterion, of having read and enjoyed the novel before (28 responses), further emphasizes the benefit of familiarity to aid comprehension as a strategy that many students employ. Within this group, some students further explained if they had read it in English or their L1, and if for leisure or in a school context. The value of rereading may also partly account for the frequency of the reason ‘I saw the film or TV series’ (6 responses), which is always a popular strategy for introducing literature in the classroom (cf. Duncan & Paran, 2018; Fazzi, 2023). The answers also show that recent films of famous books inspired students to tackle classics. Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 film of The Great Gatsby remains well-known in popular culture today, while recent screen versions of Rebecca (Netflix, 2020), Vanity Fair (series, 2018) and Little Women (film, 2019) may account for the interest in novels that Austrian late teens are unlikely to otherwise know.

The results show obligation to be a weak motivation: a sense of needing to read a ‘must-read’ classic garnered only 11 responses, evenly split between ‘yes’ and ‘maybe’ evaluations. ‘No’ responses revealed reasons for not reading that were often more about the students’ personal reading habits in general than about their chosen text in particular. The difficulty of a text provided an insignificant reason (2 responses), and there were no responses about a book being boring, too long, or otherwise inappropriate. Such lack of negative responses may indicate student reluctance to admit to struggling with the task, particularly given the questionnaire’s lack of anonymity.

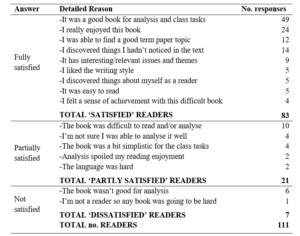

Table 5. ‘Were you satisfied with your book choice for the purposes of this class?’

Of the 126 students who answered this question, 15 gave no comprehensible response, while some gave several reasons, which is why the number of responses and number of readers differs in this data set.

The answers to this question are even more overwhelmingly positive than in the previous evaluative question. 75 per cent of the students who answered gave positive responses, although the missing answers of 15 students may be significant. In an inversion with the previous data point, these answers show satisfaction to be dominated by a sense of suitability for producing course output, in tasks, analysis and essay writing (term papers). Responses based on enjoyment were about half as frequent, with some interesting introspection about themselves as readers. The three most common reasons for not being entirely satisfied were the novel being quite complicated and thus hard work (10 responses), the novel being quite simplistic and thus not providing enough to analyze (5 responses), and analysis as ruining their reading pleasure (2 responses). The 10 readers who found their text difficult still categorized themselves as partially satisfied, and a further four students declared themselves wholly satisfied with difficult books, citing a strong sense of achievement.

The low number of negative responses about high difficulty also rejects the argument that classics alone are inappropriate for educational purposes. The novels deemed difficult by ‘partially satisfied’ readers were Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Austen’s Emma, H.G. Wells’s The Sleeper Awakes and War of the Worlds (both chosen by male non-readers), Alcott’s Little Women, Alan Paton’s Cry, The Beloved Country, Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot (a set text in another university course), and M.L. Stedman’s The Light Between Oceans. Looking outside this answer set at other comments about their novel, many more students who chose difficult texts reported a sense of pride in having managed and enjoyed a difficult text, as the following comments attest: ‘it takes a while to get into the language/writing style. So I’m glad I picked it for this class, as it really paid off – I ended up loving the novel’ (S46., Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath); ‘It was sometimes hard to follow the story line and it takes a while until you really understand who is who in the book. But in the end, I can be very proud of myself, because I managed to read such a big book’ (S22., Austen, Emma); ‘I am satisfied with the choice, because it actually is a good read and offers some more advanced/challenging vocabulary and sentence structures, which I am very into’ (S62., Austen, Pride and Prejudice); ‘the first time I read it I already loved it even though I didn’t understand everything like I understand now. I’ve been obsessed with the novel ever since, that’s why I chose it’ (S39., Tartt, The Secret History).

Discussion

The study shows that in an educational context, Austrian ELT tertiary students choose to read a novel marketed for adults (49 per cent) or a classic (31 per cent) over and above YA fiction (20 per cent). The three quantitative tables about book choice offer a more complex picture of students’ choice than much educational research on the benefits of YA would predict, as the Linz study does not fully support the common argument that YA is particularly attractive and relevant to young readers and the ELT educational environment, if this includes student teachers. The students’ significant interest in classics and canonical texts suggests a mismatch in the discourse around youth reading desires and practices.

A number of academic articles that promote choice and YA content as keys to stimulating reader motivation directly contrast these with literary classics, which are always assumed to be forced on students by teachers or because of a curriculum set-reading list. This argument is found in research both in L1 contexts (Bushman, 1997; Coles, 2020; Wexler, 2019) and in ELT (Bland, 2019; Duncan & Paran, 2018; Fazzi, 2023; Thompson & McIlnay, 2019). In the former context, Jane Coles argues against a certain ‘“weaponizing” of the British secondary classroom [that] “foregrounds texts not readers”’ and tends to represent a narrow range of material, some of which may be ethically problematic, or at least outdated (Coles, 2020, p. 108). In the ELT context, Janice Bland deconstructs the typical claims of literary and educational superiority to argue that the canon ‘is usually determined for reasons that have little to do with educational value, and may not be as attached to literary value as at first appears’ (Bland, 2019, p. ii). Thompson and McIlnay, in the US context of compulsory education (K-12) in both L1 and ELT, summarize the contradictions between curriculum objectives and the methods used to achieve them:

The required reading list and loss of choice in terms of reading material conflicts with developmental expectations of increasing autonomy for students in this age range; the education system disciplines students while the social structure encourages autonomy, independence and agency. (Thompson & McIlnay, 2019, p. 65)

Such points, while valid, often mix up literary content and teaching method: the above quotes assume that the canonical texts are imposed rather than chosen, feature text-analysis over reader-oriented approaches, and respond more to the teachers’ knowledge and value systems than to those of students.

By contrast, the Linz study suggests that many student teachers are motivated to read classics when given free choice that may include support such as familiarity in the form of having read it before (perhaps in L1 or in graded readers) or having seen the film or series. The results rather suggest that students do not shy away from classics, canonical or other difficult or long texts (such as sci-fi/fantasy sagas), especially when they are offered the classroom support and structure for tackling literary interpretation, including student-centred methodologies, reader-response and creative response. These findings have positive repercussions for teachers, both in ELT and L1 contexts, to encourage students to engage with classics rather than shy away from them on the grounds of difficult language and purportedly outdated content. As the qualitative data from the Linz study report, these factors rarely detract from student enjoyment or satisfaction, and may even heighten the reading experience through a sense of achievement and discovery of great literature.

A closer look at the shared features between YA and many classics may further help dismantle preconceptions about the unique features of each of these genres. As illustrated in Tables 1 to 3, many of the classics have a clear YA focus. Little Women, Austen’s romances, and Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye feature YA and New Adult protagonists in coming-of-age stories, while L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland were written with a clear youth readership in mind. As Table 3 shows, there are many genre or content-based similarities between classics and YA, as well as between classics and what would today be called genre fiction. Jane Austen’s romances, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, and H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine were, at their time of writing, dismissed by the literati as low-brow popular fiction, and have only retrospectively become classified as canonical. Students’ motivations in seeking out such texts may thus have as much to do with generic features as with the cultural prestige of reading a classic, and this is reflected in the high levels of reader satisfaction based on emotive responses of pleasure.

The popularity of adult genre fiction in the Linz study also suggests that this larger category deserves closer attention in high school and ELT educational research, to better understand students’ motivations and interests. In the Anglophone university English department, genre fiction, like YA, has fought a long battle for recognition and respect, to finally take its place on the curriculum in many places. Interpretative methodologies from cultural and media studies, affect, and postcritique have certainly aided this acceptance (Anker & Felski, 2017; Felski, 2008, 2015; Gelder, 2004; Glover & McCracken, 2012; Grossberg, 1997; Lewis, 1992; Wilkins et al., 2023). As future teachers increasingly gain experience working with popular genre fiction and YA in their own university studies, this may lead to a spill-over effect on secondary education in the twenty-first century.

The Linz survey booklist certainly shows the difficulty of distinguishing between YA and fiction for adults, especially at the upper end of the YA age scale that blurs into New Adult with readers in their late-teens and early twenties. Rather than a clearly defined genre, the most-read content was that which we labelled ‘relationships/life drama’, which includes but is not restricted to coming-of-age experiences, family, friends, and romantic relationships, and issues of identity, mental health, trauma and grief. The most-read author and novel, Sally Rooney’s Normal People, typifies the kind of novel that appeals to these students: the protagonists are in high school and university, and the plot concerns issues of identity, mental health struggles, social pressures, career choices, dealing with parents and family, sex and love. Novels with twenty-something protagonists by Moyes, Sparks, Haig, and Hornby similarly fit these criteria, as do a number of genre novels chosen by only one reader, often new releases promoted through social media. The range of books chosen thus mirror the broad definitions and unclear demarcations of YA and NA, which can be seen as indicative of the fluidity of identity-making that these students are themselves experiencing.

Genre categories are also somewhat helpful in breaking down borders between YA and adult, as between popular and canonical. The sci-fi/fantasy writers Douglas Adams, Terry Pratchett and Stephen King have always been particularly popular with teens, which this study shows to be no less the case in ELT than in native-speaker contexts, even 20 to 30 years after their original publication. The genre of sci-fi/fantasy, which was the most-read genre overall, is also present in chosen classics, with Bradbury, Orwell, Tolkien, and Wells appealing to multiple readers. Romance similarly shows cross-over appeal between YA and adult genre fiction, with Taylor Jenkins Reid, Jojo Moyes, Nicolas Sparks, and the Chinese danmei writer Mo Xiang Tong Xiu all bestselling authors during the years of the Linz study, when these books in English were circulating on BookTok and Goodreads and were stocked in Linz bookshops.

The other significant group of adult genre novels with a large readership of committed readers comprise multi-book series and storyworlds, even though students were discouraged from choosing such books, as characterization and narrative structure are often harder to identify. New fantasy series by Leigh Bardugo, Glen Cook, and Sarah J. Maas join the established writers Pratchett, C. S. Lewis, and Tolkien. Older bestselling mystery writers Lee Child, Agatha Christie, Ken Follett, and Jack Higgins (each one or two readers) also found readers of a much younger generation, while Colleen Hoover has almost established a genre of her own in ‘dark’ romance, often with a thriller structure. These popular new writers and story-worlds, with their dedicated fans, transmedial and multimodal adaptations, and social media promotion and writer-fan interactions, indicate significant youth involvement in literary media worlds that formal education struggles to engage in.

The study unequivocally shows a correlation between reader choice (Tables 1 and 2) and book enjoyment (64 per cent) and satisfaction (75 per cent), even in an educational context (Tables 4 and 5). The overall high number of positive responses goes against the popular, often alarmist (Keen, 2007; Thompson & McIlnay, 2019) argument that interest in reading is waning, or that teachers struggle to motivate their students to read (Applegate & Applegate, 2004; Applegate et al., 2014; Beck, 1995; Duncan & Paran, 2018). The positive spin in this study may stem from the lack of anonymity in the questionnaire, and the end of semester and in-class context of data collection that followed their successful completion of the course assessment items. However, this assumption of positive bias as stemming from self-selected ‘good’ students of English is undermined by Spann and Wagner’s study, based on earlier cohorts of the same Linz student population, which found a disconcerting lack of enjoyment in reading and a low number of students who identify as avid readers. Such a pragmatic approach to literature, they argue, supports Cremin (2020) and the earlier Applegate and Applegate (2004) and Applegate et al. (2014) for a ‘Peter Effect’ by which teachers believe reading is important but, as non-avid readers themselves, are unlikely to pass on a keen interest in reading to their students (Spann & Wagner, 2022; see also Beck, 1995; Duncan & Paran, 2018). While our current Linz study suggests a much more optimistic picture, further analysis of the data is required to discover how the students themselves envisage the transfer of the ABC Approach into their own future teaching. More long-term, we aim to follow these Linz students to discover what opportunities and restrictions they face in implementing literature projects in their own classroom praxis. Longitudinal studies are also required to follow up on the implementation of the CEFR reading scales and the Austrian secondary curriculum call for more use of creative media in the language classroom.

Conclusion

The present study suggests the need for more nuanced discussion about what kind of literature young people choose to read, and thus which literary texts are deemed suitable for late high school and early tertiary reading options. The quantitative data suggests that both classics and fiction for adults appeal to such readers, in part because they contain factors similar to YA and fit genre conventions that students are familiar with and enjoy. The study thus suggests the need for more educational research on mainstream popular fiction in relation to YA, to understand how bestsellers circulate within student populations, a topic that will necessarily encompass multi-media, transmedial, and fan interaction with texts, visual adaptations, and social media influence. The qualitative data suggest that negative attitudes to canonical texts and classics, including educators’ judgements of a text’s difficulty or irrelevance, are partly unfounded, as these may be at odds with young-adult readers’ perceptions and motivations, which include cultural prestige, linguistic challenge, and curiosity for and familiarity with famous texts and genres. The wide range of texts chosen by these students certainly reflect the wide variability of students’ experience with literature at school. However, against the negative evaluation of such unevenness in other studies (Beck, 1995; Cremin, 2020; Spann & Wagner, 2022), the students’ overall positive experience with their book choice suggests it is not necessary to take a deficit perspective to this diversity. Students’ multifarious motivations for their choices, including reading for pleasure and reading for educational purposes, in each case lead to a wide range of literary texts, spanning fiction for adults, classics and YA.

References

Anker, E., & Felski, R. (Eds.). (2017). Critique and postcritique. Duke University Press.

Applegate, A. J., & Applegate, M. D. (2004). The Peter effect: Reading habits and attitudes of preservice teachers. The Reading Teacher, 57(6), 554–563.

Applegate, A. J., Applegate, M. D., Mercantini, M. A., McGeehan, C. M., Cobb, J. B., DeBoy, J. R., Modla, V. B., & Lewinski, K. E. (2014). The Peter effect revisited: Reading habits and attitudes of college students. Literacy Research and Instruction, 53(3), 188–204.

Beck, R. (1995). Macbeth, Animal Farm und kein Ende! Was haben Studienanfänger in der Anglistik gelesen? Neusprachliche Mitteilungen aus Wissenschaft und Praxis, 48, 31-38.

Bland, J. (2013). Children’s literature and learner empowerment. Bloomsbury.

Bland, J. (Ed.). (2018). Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8-18 year olds. Bloomsbury.

Bland, J. (2019). Editorial: Extensive reading and deep reading in ELT. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 7(1), ii–v.

Blau, S. D. (2003). The literature workshop: Teaching texts and their readers. Heinemann.

Bloemert, J., Jansen, E., Paran, A., & Van der Grift, W. (2017). Students’ perspective on the benefits of EFL literature education. The Language Learning Journal 47(3), 371–384.

Bundesministerium Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung Lehrpläne [BMBWF] (2023). (Erste) Lebende Fremdsprache (Sekundarstufe I). PÄDAGOGIK-PAKET. https://www.paedagogikpaket.at/massnahmen/lehrplaene-neu/materialien-zu-den-unterrichtsgegenst%C3%A4nden.html

Bushman, J. (1997). Young adult literature in the classroom–or is it? The English Journal, 86(3), 35–40.

Coles, J. (2020). Wheeling out the big guns: The literary canon in the English classroom. In J. Davison, & C. Daly (Eds.), Debates in English teaching (pp. 103–117). Routledge.

Council of Europe. (Ed.). (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Council of Europe.

Council of Europe. (Ed.). (2018). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment: Companion volume with new descriptors. Council of Europe.

Cremin, T., Mottram, M., Powell, S., Collins, R., & Safford, K. (2014). Building communities of engaged readers: Reading for pleasure. Routledge.

Cremin, T. (2020). Reading for pleasure. In J. Davison, & C. Daly (Eds.), Debates in English teaching (pp. 91–102). Routledge.

Davison, J., & Daly, C. (Eds.). (2020). Debates in English teaching (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Day, J., & Bamford, R. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: Reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research, 71(1), 1–27.

Delanoy, W., Eisenmann, M., & Matz, F. (Eds.). (2015). Learning with literature in the EFL classroom. Peter Lang.

Duncan, S., & Paran, A. (2018). Negotiating the challenges of reading literature: Teachers reporting on their practice. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8-18 year olds (pp. 243–259). Bloomsbury.

Eisenmann, M., & Summer, T. (2020). Multimodal literature in ELT: Theory and practice. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 8(1), 52–73.

Fazzi, F. (2023). Reflecting on EFL secondary students’ reading habits and perceptions of young adult literature to promote reading for pleasure and global citizenship education. EL.LE, 12(2), 251–272.

Felski, R. (2008). The uses of literature. Blackwell.

Felski, R. (2015). The limits of critique. University of Chicago Press.

Gelder, K. (2004). Popular fiction: The logics and practices of a literary field. Routledge.

Glover, D., & McCracken, S. (Eds.). (2012). The Cambridge companion to popular fiction. Cambridge University Press.

Grimm, N., Meyer, M., & Volkmann, L. (2015). Teaching English. Narr Francke Attempto.

Grossberg, L. (1997). Dancing in spite of myself: Essays on popular culture. Duke University Press.

Keen, S. (2007). Empathy and the novel. Oxford University Press.

Kirchhoff, P., (2016). Is there a hidden canon of English literature in German secondary schools? In F. Klippel (Ed.), Teaching languages – Sprachen lehren (pp. 229–248). Waxmann.

Kirchhoff, P., (2019). Kanondiskussion und Textauswahl. In C. Lütge (Ed.), Grundthemen der Literaturwissenschaft: Literaturdidaktik (pp. 219–230). De Gruyter.

Knickerbocker, J., & Rycik, J. (2020). Literature for young adults: Books (and more) for contemporary readers. Routledge.

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture. Oxford University Press.

Krashen, S. D. (2011). Free voluntary reading. Libraries Unlimited.

Lewis, C., & Dockter, J. (2011). Reading literature in secondary school: Disciplinary discourses in global times. In S. A. Wolf, K. Coats, P. Enciso, & C. A. Jenkins (Eds.), Handbook of research on children’s and young adult literature (pp. 76–91). Routledge.

Lewis, L. (Ed.). (1992). The adoring audience: Fan culture and popular media. Routledge.

Nilsen, A., Blasingame, J., Donelson, K., & Nilsen, D. (2012). Literature for today’s young adults (9th ed.). Pearson.

Nünning, A., & Surkamp, C. (2006). Englische Literatur unterrichten: Grundlagen und Methoden. Klett Kallmeyer.

Nünning, A. (1997). Literatur ist, wenn das Lesen wieder Spaß macht. Der fremdsprachliche Unterricht Englisch, 3, 4–8.

Reichl, S. (2009). Cognitive principles, critical practice: Reading literature at university. V&R Unipress.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1994). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Southern Illinois University Press.

Schreyer, R. (1978). Englische Oberstufenlektüre in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Neusprachliche Mitteilungen aus Wissenschaft und Praxis, 31, 82–90.

Showalter, E. (2003). Teaching literature. Blackwell.

Spann, H., & Wagner, T. (2022). Reading habits and attitudes in first year EFL student teachers and their implications for literature course design in an Austrian study programme. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 36(2), 240–256.

Tomlinson, E. (1998). And now for something not completely different: An approach to language through literature. Reading in a Foreign Language, 11(2), 177–189.

Thaler, E. (2008). Teaching English literature. Schöningh.

Thompson, R., & McIlnay, M. (2019). Nobody wants to read anymore! Using a multimodal approach to make literature engaging. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 7(1), 61–80.

Volkmann, L. (2016). Functions of literary texts in the tradition of German EFL teaching. In B. Schaff, J. Schlegel, & C. Surkamp (Eds.), The institution of English literature formation and mediation (pp. 179–206). V&R Unipress.

Wexler, N. (2019). The knowledge gap: The hidden cause of America’s broken education system – and how to fix it. Avery.

Wilkins, K., Driscoll, B., & Fletcher, L. (2023). Genre worlds: Popular fiction and twenty-first-century book culture. University of Massachusetts Press.

Wolf, S. A., Coats, K., Enciso, P., & Jenkins, C. A. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of research on children’s and young adult literature. Routledge.

Appendix

The feedback survey, filled in on the online platform Moodle, and thus not anonymous, asked questions about the reader’s relationship to fiction in general, and to their chosen book in particular:

- Title, author, publication date of your chosen novel

- How many novels do you read per year?

- How many of them are in English?

- Which genres do you usually read?

- How and why did you choose your class novel?

- Would you have read this novel if you didn’t have to for the class? Why/why not?

- Are you satisfied with your choice of novel for the purposes of this class?

- Comments on the ABC approach to literature

[i] The expectation was that pair work would make for more in-depth discussion and analysis of

the novel, but in fact students who chose this option reported lower satisfaction due to having

to compromise with their partner on choice, and the teachers noted that pair work tended to

coalesce opinion rather than expand it. The ‘pair’ has been factored out of this data set.