| Exploring identity and belonging with Frank Tashlin’s The Bear that Wasn’t

Beth Lewis Samuelson |

Download PDF |

Abstract

In this paper I discuss an approach to using Frank Tashlin’s graphic novel, The Bear that Wasn’t, to guide pre-service language teachers in how to integrate discussions of difference and ascribed identity into their language classrooms (e.g., English language teaching and world languages). Originally published in 1946, the graphic novel tells a tale of belonging and identity in the face of confusion and disruption. The narrative centres on a bear who is mistaken for a man and struggles to reclaim his true self. It has lasting relevance for its treatment of identity politics, discrimination, and equity. The sequence of activities presented, including identity charts, textual analysis, and readers theatre, are designed to enable language teachers to honour and sustain learners’ diverse cultural and linguistic identities. The activities are scaffolded to support comprehension, analysis, evaluation, and transformation. The story has lasting relevance for its treatment of identity politics, discrimination, and equity and can engage children, young adults, and adult learners.

Keywords: identity, language awareness, English language teaching (ELT), world languages, teacher professional development, graphic novels, literacy methods

Beth Lewis Samuelson is Associate Professor in the School of Education, Indiana University. She is interested in language learning, language awareness, language policy, and literacy planning. She has an interdisciplinary orientation that has resulted in interdisciplinary work in other areas, most recently in African studies and open education resources.

Introduction

The Bear that Wasn’t (Tashlin, 1946) is a story of self-discovery and self-understanding that offers important ideas that are accessible to learners of all ages. The bear’s journey from his den and back offers teachers an opportunity to integrate discussions about identity into a variety of lesson topics. The examples offered here are from teacher development for English language teaching (ELT) and world languages education. Pre-service teachers use The Bear that Wasn’t as a means of addressing double-consciousness (Du Bois, 2015 [1903]) and the hidden curriculum of ELT textbooks and materials, which can perpetuate biased representations of topics related to language, culture, race, and gender in ways that favour the worldviews of select groups over the perspectives and rights of the Other (Kamasak, Ozbilgin & Atay, 2020; McLaren, 2014).

This short graphic novel chronicles the life of a bear who, following the annual cycles of his life, hibernates through the winter in his cave. While he is sleeping, people come with steam shovels and bulldozers and build a factory on top of his cave. When he wakes up and finds his world completely changed, the bear’s supervisor orders him to resume work on the assembly-line. The bear objects, but he is disoriented. The people around him try to convince him that he is not a bear at all, but just ‘a silly man who wears a fur coat and needs a shave’ (Tashlin, 1946, unpaginated). In a series of amusing encounters, he meets the factory’s managers and bosses, who all agree that he is not a bear. He also meets captive bears at the zoo and the circus, who also do not consider him to be a bear because he does not live in a cage or dress like a performing bear. These interactions lengthen the bear’s uncertainty about his identity, and he returns to the factory work on the assembly line. When the weather starts to get cool in autumn, he realizes that he really is a bear. So, he returns to his forest and hibernates in his den.

Regarding a hidden curriculum in ELT, Kamasak, Ozbilgin and Atay (2020, p. 108) contend: ‘The culture that informs the core cultural elements of the curricula would have a significant advantage and dominating force on the non-native learner, subjecting them to cultural domination and symbolic violence’. Many language teaching curricula have historically presented idealized depictions of cultures, peoples, and practices. In ELT, for instance, the dominance of British and US varieties of English has meant that many textbooks have portrayed monocultural and colonial outlooks, which amounts to symbolic violence on non-native learners of English. Chinua Achebe (1959) famously recounted the experience of Okonkwo’s son Nwoye, who read Wordworth’s ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’, while learning English at a mission school in Nigeria and had never seen the daffodils that featured in the poem. Culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 2021), culturally sustaining pedagogy (Paris & Alim, 2017), and translanguaging pedagogy (García, Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017) have provided avenues toward mitigating and erasing such dominant discourses. All these approaches foreground the inclusion of cultural and linguistic identities that have often been unrecognized by schooling. The symbolic violence experienced by Nwoye can be replaced by educational experiences that honour, support, and sustain the home cultures and identities of the students. The Bear that Wasn’t offers an entry point to discussions and activities that invite students to reflect on their experiences with cultural and linguistic mismatches that they have encountered in their studies. For many culturally and linguistically diverse students, a feeling of disconnection from the culture and curriculum of schooling is a common experience (Kamasak, Ozbilgin & Atay, 2020).

While the ELT profession has become more concerned with incorporating the plurilingual and diverse cultural identities of children into teaching and learning (Bland & Mourão, 2018), much is yet to be done to address the hidden curriculum of schooling that perpetuates inequalities and favours the world views of select groups over the perspectives and rights of others. The Bear that Wasn’t offers an introductory lesson to guide learners in considering how they and others see themselves and offering them time to reflect on how they can stand up for themselves and their identities.

The struggle to maintain one’s identity has been a common theme for the minoritized, immigrants, and refugees, as they, like language learners, must acquire new linguistic and cultural behaviours while also maintaining their sense of self. Resisting recognition of diversity and symbolically erasing differences (Ahmed, 2007, 2016) are themes that have been identified as double consciousness originated in W. E. B. Du Bois’s articulation of the spiritual state of Black Americans. In his own words, double consciousness is

this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. (Du Bois, 2015 [1903], p. 5)

Double consciousness arises wherever vast differences in social conditions and opportunities for minorities defined as ‘other’ lead to misrecognition or perceived erasure of identity. Students may acquire demeaning or derogatory views of themselves, their cultures, families, or languages. They may become confused about two different and distinct sets of beliefs or attitudes about themselves and their own groups, leading them to feel ambivalent or indecisive about themselves and their social situations. Double-consciousness obscures essential elements for a healthy self-esteem and leaves individuals prone to manipulation by people who may wish to exploit them. The protagonist of The Bear that Wasn’t was afflicted with his own form of confusion and ambivalence when he arrived at the factory only to be told that he was not a bear at all. He encountered metaphorical walls that resisted his efforts to correct the misrecognition of his identity as a bear. Narratives of exclusion and labelling frequently characterize the lives of children, whether based on race, age, socioeconomic status, gender, or language proficiency. In this context, The Bear that Wasn’t, with its themes of belonging and identity and listening to oneself rather than to the crowd, is more relevant than ever.

These themes can help initiate discussions about identity in a range of disciplinary contexts, including literary analysis, reading comprehension, history, environmental science, or social sciences. Some secondary themes include democratic dialogue (Pace & Kasumagić-Kafedžić, 2021), environmental protection, and anti-hierarchy. The narrative is accessible to readers of all ages and cultural backgrounds, offering a reading that aligns with humanizing pedagogies and curricula for students from diverse cultural, linguistic, and religious backgrounds (Al-Amri, 2010; Tomlinson, 2014). Because the story includes illustrations and avoids complex language, it is suitable for a wide range of reading abilities.

To illustrate how this text can contribute to discussions about identity, I will discuss the background of the story and introduce cases of it being used, including my own. The next section begins with an overview of its many translations and adaptations, and some previous pedagogical applications.

Frank Tashlin’s The Bear that Wasn’t

Frank Tashlin, author and illustrator of The Bear that Wasn’t, had a varied career as an animator, cartoonist, scriptwriter, and movie director. The Bear that Wasn’t first appeared in 1946 and has been reissued by Dover Press (Tashlin, 1995, 2007, 2015) and by the New York Review (2010). A National Public Radio interview (Simon, 2010) noted that the graphic story contains sufficient satire to appeal to adults, as the story critiques corporate hierarchy and underscores human-induced environmental destruction and its consequences. Other themes and concepts include being and nonbeing, scepticism about being, contrasts between appearances and reality, and the epistemological foundations of knowing–all presented in a narrative that is accessible to young children (Matthews, 2021).

The story inspired a Metro Goldwyn Mayer cartoon (Jones and Noble, 1967), was anthologized in two Looney Tunes DVD collections (Blanc & Warner Home Video, 2005; Warner Home Video, 2012), and was produced in an audiobook read-aloud (Wynn et al, 1953). The story also received considerable attention in the 1940s and 1950s, when it was praised as a model of storytelling (Casebier, 1954), recommended for use with struggling readers (Heagy & Amato, 1958), and offered as a suitable reading for returning World War II veterans struggling with re-entry into civilian life (Neprude, 1947).

Making use of translations and multimodal adaptations

The Bear that Wasn’t has been translated or adapted in nine languages: Braille, Catalan, Czech, Danish, Dutch (adaptations only), French, German, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, and Spanish. At Indiana University, these texts have enriched literacy methods courses for world languages teachers. The state of Indiana certifies secondary teachers in several languages: American Sign Language, Arabic, French, German, Greek, Japanese, Korean, Latin, Mandarin, and Spanish, as well as dual language and heritage language learning (Indiana Department of Education, 2019). Due to small numbers, combined groups of pre-service teachers for Spanish, French and German (and sometimes Latin and Russian), often meet – although Spanish is the most popular choice. Multiple translations of The Bear that Wasn’t, along with the English original, have provided the foundation for the activities described in this article, including readers theatre adaptations and textual and visual analysis.

In addition to the translations, additional multimodal and multilingual versions and adaptations of the work have been made. In Spanish, it has been adapted as a puppet drama, O Sos O No Sos (Bianchi et al, 2005). French adaptations include a read-aloud, Marilou Lit: Mais Je suis un Ours (Bibliothèque Nivelles, 2020) and the drama, Je suis un Ours! by Gilles Gauthier (1982). In Dutch, the narrative has been adapted in a music video, De Beer die Geen Beer Was, by Anneke van Giersbergen and Martijn Bosman (2011). Dick Snellenberg’s Dutch video (2014) of a family attending a production of a play uses music by van Giersbergen and Bosman. In German, the story has been adapted to music in multiple releases by Reinhard Mey, who in 2020 stated that the song is his longest (11 minutes) and that it was based on the German version of the story, entitled Der Bär, der ein Bär Bleiben Wollte (Müller, Steiner & Tashlin, 1989). For an appreciation of the impact of The Bear that Wasn’t, consult the lists of the translations and remediations in Appendices I and II.

Previous pedagogical applications

Tashlin’s graphic novel is referenced in Once Upon a Time: Using Stories in the Language Classroom as an example for using literature for drama activities (Morgan & Rinvolucri, 1988). Learners name roles from the story (the bear, the supervisor, a manager, a zoo bear, a fluttering leaf) and work individually as directors to cast these roles, deciding how the actors should play them. Non-sentient roles such as the fluttering leaf help to highlight environmental messages, including a strong critique of technological change and innovation that sweeps away the natural world. Starosielski (2011) discusses the 1967 animation of The Bear that Wasn’t and the better-known The Lorax (Pratt, 1972), as examples of films that depict the environment as a malleable construct that is modified by ‘subjects, producers, and viewers’ (p. 147). This story of a bear who must struggle alone to maintain his identity has been used to stimulate discussions in reconciliation programmes, in history classes, and in teacher training initiatives. Some examples include the ‘Facing the Past’ project in Western Cape Province, South Africa (Tibbitts, 2006), a project to develop a new curriculum about Rwanda’s pre- and post-colonial history (Freedman et al., 2011), South Boston High School (Klein, 1993), and Facing History & Ourselves (Strom, 1994).

Exploring Identify and Belonging Through Comprehension, Analysis, Evaluation, and Transformation

This section is dedicated to describing the use of The Bear that Wasn’t in training courses for developing literacy instruction skills for teachers of English and other world languages. The sequence of activities is scaffolded to support comprehension, analysis of text, evaluation of text, and transformation of the text designed to help learners develop skills for making meaning from text (Kern, 2000). The themes that contribute to the graphic novel’s enduring popularity also position the text as a tool for developing critical language awareness. The Bear that Wasn’t deals with aspects of living that are common to people of all cultural groups but also touches on differences that are ineffable and must be appreciated simply for their difference and not for any evidence of similarities or commonalities. For all the efforts to force the bear to look and behave as if he were human, he stayed a bear throughout. His instincts and behaviours are not transparent for the humans and the other domesticated bears he meets. By supporting learning about the importance of identity and by developing empathy and understanding, this kind of authentic literature helps to foster critical thinking about the ways that power can be exerted over actors (human and non-human) who are vulnerable, whether due to their difference, their positions in hierarchical organization, or due to rapid changes to their environments that disrupt their ways of living and being.

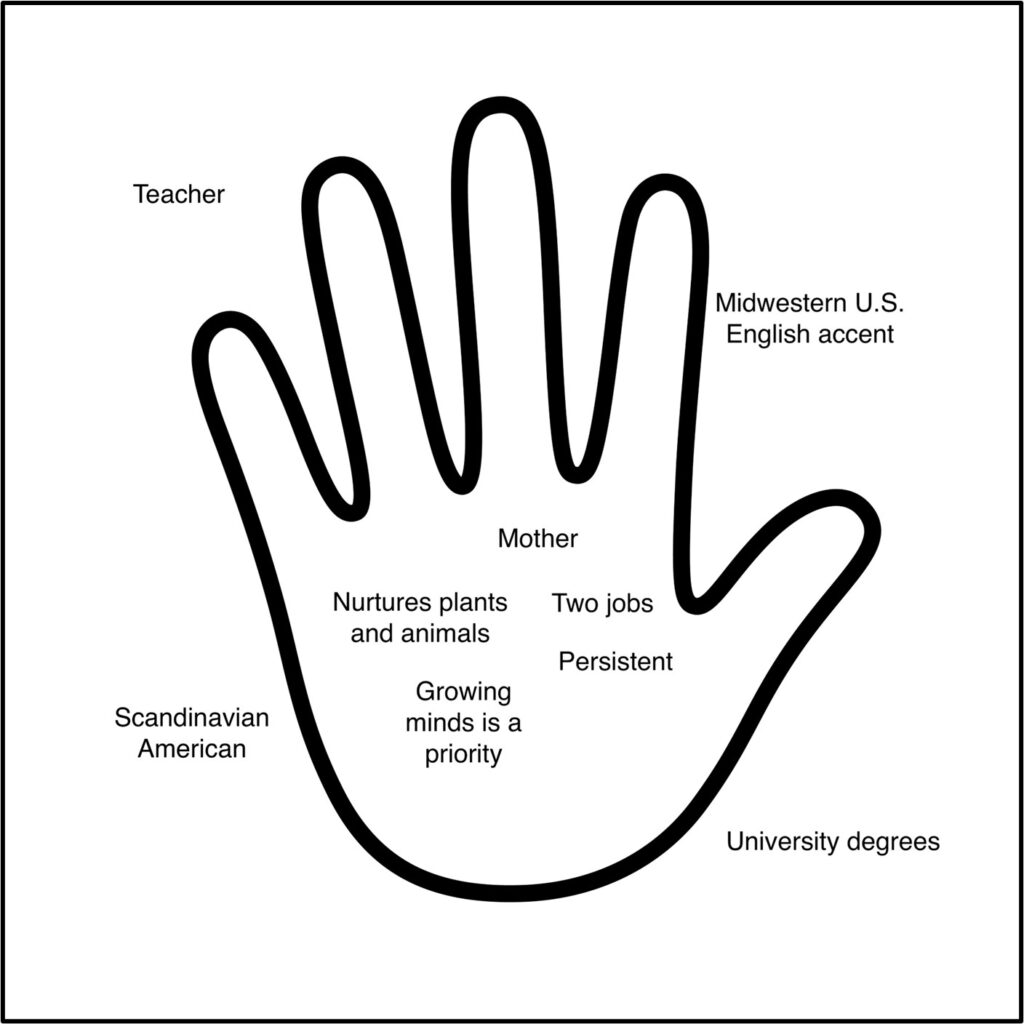

Developing comprehension: Identity charts

Identity charts are graphic tools that assist students in examining their identities through internal and external perspectives, and they can be utilized to introduce a unit or topic, or to summarize reading comprehension. Students think of the many ways that they describe themselves as well as the ways that others define them. They consider the question, ‘Who am I?’ and write down several descriptive words or phrases, and, if they wish, they can share a few selected words with a partner and later with the full group in a think-pair-share activity. They organize their descriptors into common categories, such as Accomplishments, Abilities, Skills, Family Roles, Hobbies and Interests, Background, Gender, Race, Ethnicity, etc. Then they trace their hand on a paper and start to fill it in. Within the outline, students write words or phrases that they use to identify themselves. Outside of the outline, students then write words or phrases that others use to define them. The instructor can show examples of a completed identity chart or share their own identity hand chart with students. The example (Figure 1) was developed by the instructor. Identity charts can be modified to explore the identity of an historical or literary figure, such as the bear. Students can look back through the text to find evidence to include in the chart to summarize the bear’s identity.

Figure 1. A ‘Who Am I?’ identity chart

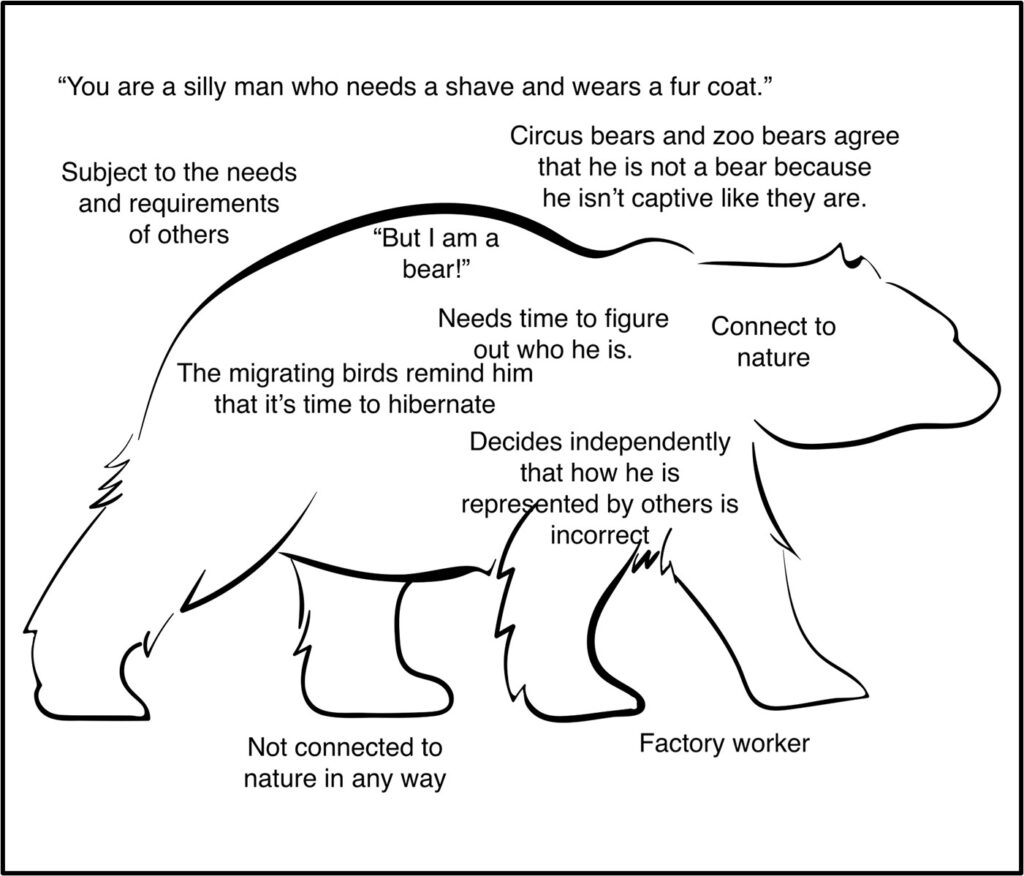

They can include direct quotes showing the views held by the humans in the factory as well as the bears at the circus and the zoo. The example (Figure 2) was developed by the instructor based on multiple classroom discussions. Students may present their charts to the class or display them in the classroom space for a time. The contrast between internal and external ascriptions of identity can promote discussion about how students may perceive themselves versus how others may perceive them.

Analysis of the story: Illustrations. Figures 3 and 4 show two covers of recent reprints of the book with the bear in contrasting story settings, each emphasizing a different theme. The covers represent a different element of the story and the bear’s struggle with control over the decisions he makes about how he will live. The New York Review (2010) cover (Figure 3) shows him working in the factory, surrounded by humans who look identical and work in unison at the same repetitive tasks. At the bottom of the illustration, under the workers and the cogs, the businessmen who administer the factory shake hands and look identical to each other as well.

Figure 2: A ‘Who is the bear?’ identity chart

Figure 3. Reprint by New York Review, New York (2010)

The Dover (2007) reprint cover (Figure 4) emphasizes the bear in his natural environment, walking into his cave for a long winter hibernation. The colours present an earthy brown-and-yellow vision of the autumnal natural environment. The bear seems to walk in a trance, his long shadow stretching out ahead, with wide eyes staring vaguely, as if he is following the instinct to hibernate.

Figure 4. Reprint by Dover Publications, New York (2007)

A comparison of these two book covers can introduce a discussion on how the emphasis on different themes in the book can result in different viewpoints: constructed factory environment versus natural environment, for example, or anonymity versus personalization.

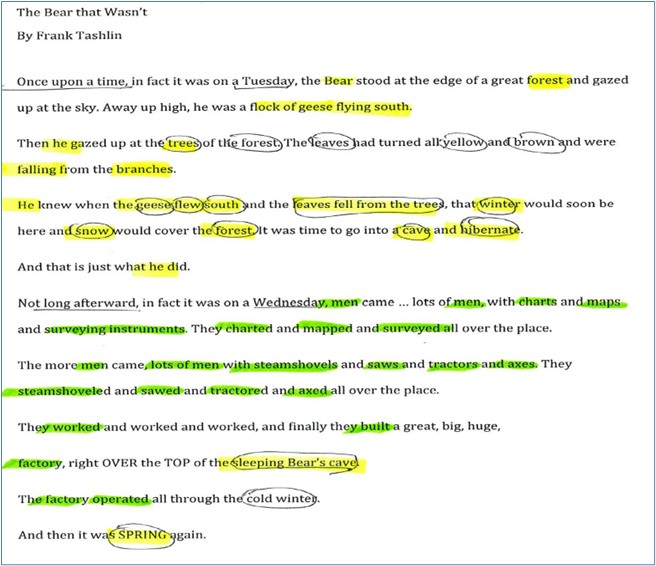

Analysis of the Story: Textual. In addition to the analysis of illustrations, a textual exploration of semantic chains invites students to explore the text and focus on how vocabulary can be used to create cohesive imagery to support a well-built story by tracing the use of semantically related words in a text. Pulling the lexical chain together helps language students to learn vocabulary strategically and link language choices made by the author to the meaning created. In the literacy methods courses, the student teachers receive copies of a section of the text to mark up their analysis. They highlight in yellow the words that are used to describe the bear and his actions and then highlight the words describing the workers and their actions in green. They underline the words about time (e.g., ‘Once upon a time’, names of days) and circle the words about nature. The group compiles its results and looks for patterns (see Figure 5). Overlap between words describing the bear and words describing nature leads to powerful discussions critiquing dichotomous conceptions of living beings and their activities. One of the patterns that emerges is the absence of nature in the section describing the building of the factory and the activities of the workers. The colours provide the contrast, and while learners are working on the patterns, they are also building their vocabulary knowledge.

Figure 5. Sample text analysis contrasting the bear’s world with the construction of the factory

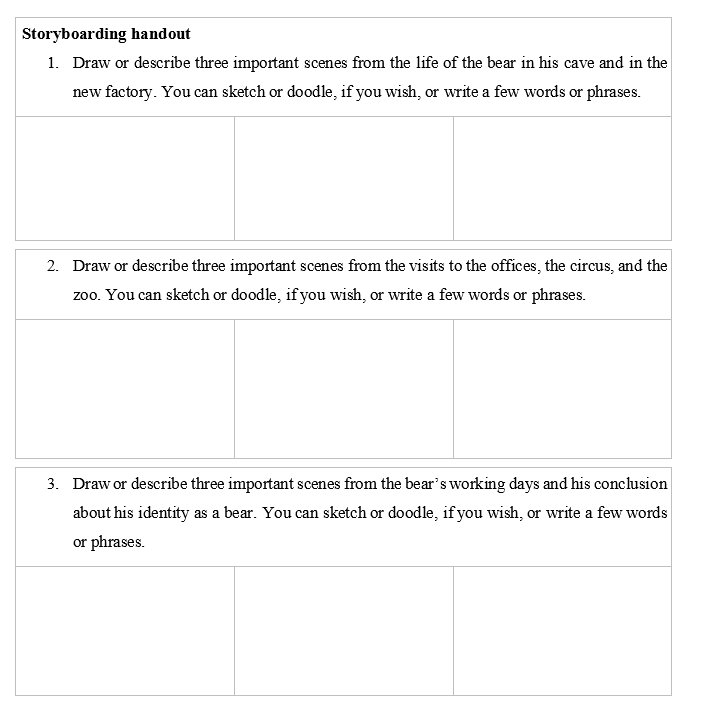

Evaluation: Narrative storyboarding

As a graphic depiction of the major events in an article or story, a narrative storyboard prompts learners to consider what the most important scenes of the story might be and to make simple drawings showing these scenes (Doherty & Coggeshall, 2005). After the students have read the text and have worked on some basic comprehension and analysis, the instructor can ask them to decide which events were the most meaningful and sketch six to eight key scenes in sequence on a storyboard. The completed storyboards can be shared during the group or whole class discussions. See Figure 6 for a sample storyboarding handout.

Figure 6: Sample storyboarding handout

Evaluation: Short summaries

Like storyboarding, the summary assignment (25-50 words) creates opportunities for pre-service teachers to focus on what they consider to be the most important aspects of the story and then use these summaries to build discussions about the choices they have made. In Kern’s terminology (2000), the summary engages learners in evaluation of the text as well as transformation of the text. The evaluation involves making choices about what is important. A comparison of students’ summaries shows how this process can vary from reader to reader. While providing an evaluation of the text by summarizing it, students make individual choices about what to write: editing, cutting, reorganizing, and selecting as they fit their ideas into the summary. The following summaries were written in a workshop for teachers visiting the United States from the Middle East and Europe:

This is the story of a bear who hibernated in the winter. Following his waking up in the spring, he saw a factory where people would ask him to work the way everyone did. And the events went on … Finally, he tried to go on believing in himself in spite of experiencing events against it.

TBTW is an allegoric fiction intended for younger readers. It is about how your environment might change all of a sudden and what obstacles you can encounter trying to find a solution. The major events of the story are going on in a forest with a bear as a main character, who has to deal with other characters of the story such as the foremen, the general manager, the first, second and third vice presidents, and the president of a big factory.

The bear learns to believe in himself despite assertions by humans and other animals that he is not a bear. When his forest is destroyed to build a factory, he spends a summer negotiating human society before deciding for himself what he is and returning to his cave for the winter.

Each student teacher focuses on aspects of the story that are most salient to them. Focusing on the bear’s persistent belief in himself, despite changes in his environment or lack of affirmation from other characters. A brief summary written in class can provide the instructor with important insight into how the students understand the story and what they are getting from it.

Transformation of the story: Creating a readers theatre script

When students can summarize the story and connect it to their analysis of the visual and verbal details, readers theatre can be introduced to help them connect reading aloud and drama to achieve a dramatic presentation of the written script (Kern, 2000). Readers use their voices, facial expressions, and limited acting to perform. Pre-service teachers select portions of the text to work from, focusing on a theme in the story. Because my classes often include students who are preparing to become world language teachers (usually Spanish and English, but also French, German, and sometimes Russian, Latin or Mandarin Chinese), they prepare scripts in small groups and perform them for the class. With less proficient students, or in workshops where there is not sufficient time for small groups to prepare their scripts, the instructor provides them with scripts prepared ahead of time. After explaining the process of readers theatre, the instructor provides some sample performances from online sources. The groups will need some time to prepare their scripts and practice their performances, particularly since they will learn more from the activity if they write their own scripts. Ideally, this means that while they initially work from the text itself, they will need to mark it up and rewrite it to reflect the decisions that they have made about pacing, intonation, volume, emphasis, etc. Since the readers theatre activity does not require props or stage choreography, the students must rely on their use of language to convey their interpretations of the themes of the story, the conflicts that the bear encounters, and any underlying meaning. After the groups give their performances in class, students take some time to reflect on participating in the readers theatre. FHAO provides some comprehensive notes for conducting this activity and recommends readers theatre for works that have strong emotional themes for the learners (Facing History & Ourselves, 2017). If further work guiding the students through transformative responses to the work is needed, art-based response and critical essays are recommended (Kern, 2000).

The pre-service language teachers applied transformation by writing multilingual scripts that adapted the story to their own lived experiences. They created and performed Latin–French or Spanish–English versions of the story. An all-Spanish group rewrote the context of the bear’s ordeal and placed him in a Starbucks coffee shop that had been built over his den and where he was compelled to work as a barista until he realized his identity as a bear was stronger than what the workers and managers in the coffee shop were telling him. For these students, the identity struggles of working in a capitalist industry that primarily viewed them as workers and not full human beings resonated with their reading of the text.

Other possibilities for transforming the story allow students to differentiate their work according to their interests. Students can choose the product that they make, but they are assigned specific content, namely the book that they have read in class. Some ideas include:

I have students create a new chapter for the book, imitating the author’s writing style, incorporating one or more of the characters and the general philosophy of the book, complete with an illustration and a ‘quotable quote’ of their own making. It basically tests everything we focus on during our readings. However, it may take the form of a storyboard, a postcard, a standard chapter, a video, a rap, or a narrative poem. (Blaz, 2016, p. 151)

Activities like these that require students to transform or rework the story allow them to demonstrate deep understanding and create something that is original.

Conclusion

The Bear that Wasn’t offers a range of opportunities to discuss identity and belonging, and creates openings for discussion with students of all ages, both English learners and learners of other languages. The beauty of the language and the graphics allow for analysis and evaluation that can lead to productive transformation and performance where students show what they have absorbed from this story. Because the book has been translated into multiple languages, it offers the possibility of multilingual lessons and performances for learners of various languages. The scaffolded activities described here will inspire teachers and teacher educators to use the text to prompt discussions about the diverse identities and perspectives of their students.

Bibliography

Achebe, Chinua. (1959). Things fall apart. Fawcett.

Blanc, Mel, & Warner Home Video. (2005). Looney Tunes Golden Collection [DVD]. (Vol. 3). Warner Home Video.

Tashlin, Frank. (1946). The Bear that Wasn’t (1st ed.). E. P. Dutton. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000598492

Tashlin, Frank. (1995). The Bear that Wasn’t. Dover Publications.

Tashlin, Frank. (2007). The Bear that Wasn’t. (2nd ed.). Dover Publications.

Tashlin, Frank. (2010). The Bear that Wasn’t. New York Review Books.

Tashlin, Frank. (2015). The Bear that Wasn’t. (eBook). Dover Publications.

Pratt, Hawley. (Director). (1972). The Lorax [Television special]. DePatie-Freleng Enterprises.

References

Ahmed, S. (2007). A phenomenology of whiteness. Feminist Theory, 8(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700107078139

Ahmed, S. (2016). How not to do things with words. Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s & Gender Studies, 16, 1–10. https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/wagadu/vol16/iss1/1/

Al-Amri, M. (2010). Humanizing TESOL curriculum for diverse adult ESL learners in the age of globalization. International Journal of the Humanities, 8(8), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9508/CGP/v08i08/42995

Bland, J., & Mourão, S. (2018). ELT as a pluricultural space. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 6(2), ii–v. https://doaj.org/article/ea3fbc957ac840c6a66bdd260c93ca58

Blaz, D. (2016). Differentiated instruction: A guide for world language teachers (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Doherty, J., & Coggeshall, K. (2005). Reader’s theater and storyboarding: Strategies that include and improve. Voices from the Middle, 12(4), 37–43. http://www.ncte.org/journals/vm/issues

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2015). The souls of black folk. (J. S. Holloway, Ed.). Yale University Press.

Facing History & Ourselves. (2017). Reader’s theater. http://www.facinghistory.org/resources/strategies/readers-theatre-exploring-emo

Freedman, S. W., Weinstein, H. M., Murphy, K. L., & Longman, T. (2011). Teaching history in post-genocide Rwanda. In S. Straus & L. Waldorf (Eds.), Remaking Rwanda: State building and human rights after mass violence (pp. 297–315). University of Wisconsin Press.

García, O., Johnson, S. I., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Caslon.

Heagy, D. M., & Amato, A. J. (1958). Everyone can learn to enjoy reading. Elementary English, 35(7), 464–468. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41384793

Indiana Department of Education. (2019). Academic standards for world languages. https://www.in.gov/doe/students/indiana-academic-standards/world-languages-and-international-education-2019/

Jones, C., Noble, M., & Tashlin, F. (2005). Tish Tash–The animated world of Frank Tashlin [short film]. In Looney Tunes Golden Collection [DVD]. (Vol. 3). Warner Home Video.

Kamasak, R., Ozbilgin, M., & Atay, D. (2020). The cultural impact of hidden curriculum on language learners: A review and some implications for curriculum design. In A. Slapac & S. Coppersmith (Eds.), Beyond language learning instruction: Transformative supports for emergent bilinguals and educators (pp. 104–125). IGI Global. https://doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-1962-2.ch005

Kern, Richard. (2000). Language and literacy teaching. Oxford University Press.

Klein, T. (1993). ‘Facing History’ at South Boston High School. The English Journal, 82(2), 14–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/819697

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Asking a different question. Teachers College Press.

Matthews, G. B. (2021). Philosophy and children’s literature. In M. R. Gregory & M. J. Laverty (Eds.), The child’s philosopher (pp. 60–67). Routledge.

McLaren, P. (2014). Life in schools: An introduction to critical pedagogy in the foundations of education (6th ed.). Paradigm Publishers.

Morgan, J., & Rinvolucri, M. (1988). Once upon a time: Using stories in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Neprude, V. (1947). Literature in veterans’ education. The English Journal, 36(6), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.2307/806484

Pace, J. L., & Kasumagić-Kafedžić, L. (2021). Teacher education for democracy in Sarajevo and San Francisco: Pedagogical tools to connect theory and practice. Citizenship Teaching and Learning, 16(3), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1386/ctl_00073_1

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (Eds.). (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Simon, S. (Producer). (2010, February 27). The bear that wasn’t: A laugh-aloud read for kids. National Public Radio Weekend Edition [interview]. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=124148840

Starosielski, N. (2011). ‘Movements that are drawn’: A history of environmental animation from The Lorax to FernGully to Avatar. International Communication Gazette, 73(1-2), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048510386746

Strom, M. S. (Ed.). (1994). Holocaust and human behavior. Facing History & Ourselves National Foundation, Inc.

Tomlinson, B. (2014). Humanizing the coursebook. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing materials for language teaching (2nd ed., pp. 162–173). Bloomsbury.

Tibbitts, F. (2006). Learning from the past: Supporting teaching through the Facing the Past History Project in South Africa. Prospects, 36(3), 295–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-006-0013-4

Appendix I: Translations of The Bear that Wasn’t

Braille

Menville, D., & Braille Institute of America. (2002). Brailleways. (Vol. 4). Braille Institute.

Catalan

Tashlin, F., & Larreula, E. (1986). Però jo sóc un ós! Aliorna.

Czech

Tashlin, F. (1947). O popleteném medvedovi [About a confused bear]. Svoboda.

Tashlin, F., Horváthová, T., & Dvořák, J. (2006). Medvěd, který nebyl [The bear that wasn’t]. Baobab.

Danish

Tashlin, F. (1947). Bjørnen som ikke var bjørn. Fremad.

Tashlin, F. (1986). Bjørnen som ikke var en bjørn. Apostrof.

French

Tashlin, F., & Chagot, A. (1985). Mais je suis un ours! L’Ecole des Loisirs.

German

Müller, J., Steiner, J., & Tashlin, F. (1989). Der bär, der ein bär bleiben wollte. Sauerländer.

Tashlin, F., & Schneider, C. (1974). Der bär, der keiner sein durfte. Fabbri & Praeger.

Korean

Tashlin, F. (1995). 나는 곰이 아니라고요 [Nanŭn kom iraguyo]. Karam Kihoek.

Mandarin Chinese

Tashlin, F. (2012). Sen lin da xiong [森林大熊]. Tian Wei Chu Ban.

Spanish

Tashlin, F. & Minarik, E. H. (2008). El oso que no lo era. Santillana.

Tashlin, F. (1995). El oso que no lo era. Alfaguara.

Appendix II: Adaptations of The Bear that Wasn’t

Dutch

Tashlin, F. (2004). De beer die geen beer was [Book with CD]. Literair Productiehuis Wintertuin; Theater en Dansproductiehuis Generale Oost.

Giersbergen, A., van Bosman, M., & Tashlin, F. (2011). De beer die geen beer was [Music Video]. Productiehuis Oost-Nederland. https://youtu.be/OmnFi15sQz4Snellenberg,

D. (2014). De beer die geen beer was [Video]. https://vimeo.com/95834646

English

Blanc, M. & Warner Home Video. (2005). Looney Tunes Golden Collection. (Vol. 3) [DVD]. Warner Home Video.

Facing History & Ourselves. (2014a). The Bear that Wasn’t [Video]. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/video/bear-wasnt

Facing History & Ourselves. (2016a). The Bear that Wasn’t https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-1/bear-wasnt

Jones, C. & Noble, M. (Co-Directors). (1967). The Bear that Wasn’t [Motion Picture]. Metro Goldwin Mayer. https://dai.ly/x4mta9

The Bear that Wasn’t. (2010). And so it is morning dew [Music Album]. Friendly Man’s Set Up. https://thebearthatwasnt.bandcamp.com/album/and-so-it-is-morning-dew

Warner Home Video. (2012). The Looney Tunes Platinum Collection. (Vol. 1). Warner Home Video.

Wynn, K., Garrett, B., Schumann, W., Previn, A., Miller, S., Tashlin, F., Sheldon, S., Jackson, J. (1953). Keenan Wynn tells the stories of ‘The Bear that Wasn’t’ & ‘Drippy the runaway rainbow’ and Betty Garrett tells the story of ‘Fantissimo the musical horse’ [Audiobook]. Lion.

French

Bibliothèque Nivelles. (2020). Marilou lit: Mais je suis un ours [Video]. https://youtu.be/CVa12_i69iY

Facing History & Ourselves. (2014b). The Bear that Wasn’t (en français) [Video]. https://www.facinghistory.org/fr/resource-library/bear-wasnt#citation-information-664

Gauthier, G. (1982). Je suis un ours! [Drama]. Théâtre de l’Arrière Scène. https://numerique/banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2463018

German

Mey, R. (2020). Der bär, der ein bär bleiben wollte [Musical Adaptation]. https://youtu.be/S0spcA3oEkw

Spanish

Bianchi, X., Gasparini, O., Santiago, B., & Grupo de Teatro Catalinas Sur. (2005). O sos o no sos [Puppet Theater]. Hemispheric Institute Digital Video Library. https://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/j9kd51n7

Facing History & Ourselves (2016b). The Bear that Wasn’t (en español). https://www.facinghistory.org/es/resource-library/bear-wasnt-en-espanol#citation-information-210