| Integrating Drama and AI for Teaching Picturebooks in ELT

Li Ding |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This article explores the use of picturebooks by integrating drama and Artificial Intelligence (AI) within English language teaching. It draws on theoretical support from critical theories and advocates for the combination of participatory drama and AI as a transformative educational practice. The approach places learners at the centre of the meaning-making process as they interact with the text, engage their cognitive, affective, and physical responses simultaneously in a sociocultural context. Based on Chris Wormell’s picturebook, The Big Ugly Monster and the Little Stone Rabbit, I seek to illustrate how drama can be combined with text-based generative AI tools to benefit young English learners’ critical AI literacy development. The concept of AI literacy in this article builds and expands upon traditional literacy by including the critical use and assessment of AI technology. In addition, it highlights the significance of guided observation and reflection in the teaching process, which scaffolds learners’ intermedial meaning making in a creative, communal, and critical manner.

Keywords: critical AI literacy, critical theories, drama pedagogy, English Language Teaching (ELT), picturebook

Li Ding is a research associate in the English Didactics section within the Institute for English Language and Literature, Free University of Berlin. Her PhD work focuses on how drama impacts young learners’ language and literacy learning. Her new interest is on drama and AI for ELT. She has published in leading journals, such as RiDE (Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance).

Introduction: Picturebooks in Language and Literacy Education

Picturebooks bring content and meaning to primary English classrooms (Nilsson, 2023, p. 45). With the dynamic interplay of words and images and ‘the drama of the turning page’ (Bader, 1976, p. 1), picturebooks have long been the primary source of language and literature education, as well as sociocultural integration for young children (Salisbury & Styles, 2012). They tell compelling stories that kindle young learners’ interest in language (Zirkel, 2022). The interdependent visual and verbal narratives, combined with the creative overall design, offer ‘complex opportunities for discovery and interpretation of meanings’ (Bland, 2022, p. 76). Through the creative use of language, such as rhymes, alliteration, and even typography, picturebooks encourage children to become imaginative language users themselves (Valente & Mourão, 2022).

However, the content and meaning picturebooks can bring into a classroom varies significantly in accordance with our perception of the reader’s role in the reading process, which consequently influences both our choice of material and the way it is approached. Typically in an ELT classroom, a picturebook is selected based on the language it affords for a certain topic, and the purpose of its deployment is to contextualize learners’ understanding of certain lexical items (Mourão, 2016). Often, these books are concept books with a simple image-word dynamic, demanding minimal meaning-making effort from the reader (Mourão, 2016). Increasingly, however, critical literacy theory proponents, such as Salisbury and Styles (2012), argue for the use of picturebooks that encourage divergent and critical reading, particularly in today’s postmodern age characterized by digital storytelling and ‘playfulness, rule-breaking, fragmentation and uncertainty’ (p. 75). These books are preeminent as they place readers as active meaning-makers who delight in unravelling challenging themes and complex picture-word dynamics (Salisbury & Styles, 2012).

Approaching Picturebooks through Drama

In alignment with reader response theory, Mourão (2016) contends that picturebooks should be used in the classroom to engage readers personally, aesthetically, and communally, which would provide a genuine context for language use and prompt critical thinking. A picturebook is ‘a mini theatre production’ (Salisbury & Styles, 2012, p. 50) that hinges on the ambiguity between words and images and the dramatic sensation of turning pages. For young learners to enter the textual and visual world and imagine its dramatic possibilities, the classroom reading experience must be thoughtfully ‘constructed and enlivened’ (Wilhelm, 2016, p. 169). Drama has been suggested as an effective method for teaching literature in primary language classrooms (see, e.g., Surkamp, 2012; Serrurier-Zucker & Gobbé-Mévellec, 2014; Wilhelm, 2016). Arguing that ‘the page IS the stage’ (p. 13), Serrurier-Zucker and Gobbé-Mévellec (2014) perceive picturebooks as ‘a solid, productive basis’ for drama activities in the language classroom (p. 14). By dramatizing stories, such as working on characterizations, considering costumes and props, and engaging in stage rehearsals, children are involved in a creative, embodied, and social experience that enhances their motivation for learning and facilitates language acquisition (Serrurier-Zucker & Gobbé-Mévellec, 2014).

In addition to such action-oriented activities, drama classrooms also involve young learners in activities that elicit responses in writing (Surkamp, 2012). Through writing in drama, learners compose and negotiate meaning across multiple levels, including the text itself, the transaction between text and reader, and their personal meaning systems, leading to ‘complexity of stances, extensions of role, and enriched language’ (Crumpler & Schneider, 2002, p. 77). As Wang (2016) highlights, drama takes place within a sociocultural context where reading is no longer ‘a passive perception or solitary experience but an interactive communication with the text, the teacher and other readers’ (p. 62).

There is a continuum of drama approaches for language education, depending on the control teachers have in the classroom drama (Kao & O’Neill, 1998). More open forms, such as process drama, feature improvisational activities and the co-creation of dramatic worlds, and have sparked significant interest in research and practice since the 1960s (O’Toole, Stinson & Moore, 2010). Participatory drama is the term Winston (2013, 2022) uses for describing this type of improvisational and playful approach. Underpinning his practice is the principle of play, as human beings are essentially playful, and play is at the heart of both theatrical practices and creative learning and thinking (Winston, 2022). Winston (2013) typically bases his drama work on narrative texts and artfully weaves together strategies such as chants, chorus, physical and movement work, teacher in role, hot-seating, writing, poster or picture creation, and guided reflection. Through these activities, learners are guided to experience and investigate both the linguistic qualities (both written and visual signs) and the narrative potential of the text.

Drama in the Age of Information and Intelligence

In response to the global pandemic beginning in 2019, theatrical and educational drama practices were forced to adopt digital or hybrid forms. A study conducted by the European Theatre Convention across 17 countries from 2019 to 2021 revealed an 800% boom in digital theatre ticket sales (Wiley, 2022). Drama educators have been quick in keeping up with the latest technology development. As early as the turn of the 21st century, Nicholson already urged practitioners to incorporate new digital technologies into drama classrooms, not only as ‘creative means of communication’ but also ‘to provide a link between thought and practice by capturing and framing dramatic moments’ (2000, p. 164). Cameron, Anderson, and Wotzko (2017) perceive the convergence of dramatic arts and digital media as ‘the digital (code) and the analogue (human) working together to generate the new realities and worlds’ (p. 2). The three authors established creativity, playfulness, performance, and digital liveness as four common grounds between drama and digital arts, laying the foundation for creating meaningful and creative teaching and learning across various curriculum areas (Cameron et al., 2017).

Emergent research and practices on integrating drama and technology for language and literacy development were on a slow rise and then exploded during Covid-19. Digital tools and platforms such as VR rooms, blogs, and social media have found their way into drama classrooms, serving as dramatic pre-texts (Carroll & Cameron, 2009), sites of interaction (Fanouraki & Zakopoulos, 2023), or integral parts of multimodal school plays (Cannon et al., 2023). Similarly, the journal Scenario, which dedicates itself to performative language education, has seen a surge in research articles focusing on digital drama conducted via platforms like Zoom (e.g., Eikel-Pohen & Nock, 2023; Göksel & Abraham, 2022).

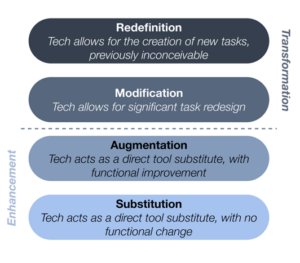

Examining the above-mentioned drama-technology integrations through Puentedura’s (2010) SAMR model on technology integration (see Figure 1), it can be seen that most of these practices fall into the category of ‘enhancement’ rather than ‘transformation’. For example, writing blog posts is only a ‘substitution’ for a traditional letter-writing task, so is playing improvisational games or performing readers theatre online for face-to-face interactions. In other words, technology has not enabled task redesign in a transformative manner. Meanwhile, perhaps due to its only recent prominence, writings on the use of AI in drama pedagogy for language teaching are very sparse.

Figure 1. Puentedura’s (2010) SAMR model

The Challenge of Integrating Drama and AI

With the release of ChatGPT by Open AI, generative AI has seized immense attention, triggering heated debates both in public discourse and academic circles. In the context of education, long before the introduction of ChatGPT, researchers and educators have been working on incorporating AI technologies into school curricula (Long & Magerko, 2020). The three main types of AI applications – machine translation tools (e.g., DeepL and Google Translate), AI writing tools (e.g., Language Tool or Grammarly), and chatbots (e.g., Siri, Duolingo) – are significantly challenging and transforming the education system and they are constantly evolving (Schmidt & Strasser, 2022). The ever-changing technology of AI has led to a re-conceptualization of literacy to encompass not only the ability to communicate through written and digital means, but also ‘the set of competencies that enables individuals to critically evaluate AI technologies; communicate and collaborate effectively with AI; and use AI as a tool online, at home, and in the workplace’ (Long & Magerko, 2020, p. 2). This set of competencies is what Long and Magerko (2020) termed as critical AI literacy.

ChatGPT opens a Pandora’s box, prompting scholars and practitioners to weigh the potentials and challenges of using AI in the foreign language classroom (Grünewald et al., 2023). At a panel discussion during the 30th congress of the German Society for Foreign Language Research (DGFF), Strasser (2023) challenged the ‘friend or foe’ dichotomy with regard to the use of technology in education. He advocated a competence-based approach to language education, which emphasizes the importance of generating functional text prompts (such as a statement to initiate a response or generate content via AI) over simply producing error-free sentences. Grünewald, Schädlich and Surkamp (2023) reverberated and elaborated on Strasser’s functional view of text prompts. In accordance with Long and Magerko’s (2020) general definition of critical AI literacy, the three authors asserted that ‘AI tools do not make language teaching unnecessary. Simply generating language or images, as done by LLMs (Large Language Models), does not amount to communication’ (Grünewald et al., 2023, p. 1). Communication in the context of foreign language learning, based on the CEFR communicative language model, is always contextualized. It involves sub-competences such as pragmatic and strategic knowledge, (inter)cultural skills, the ability to change perspectives and empathy, as well as openness to new things. Moreover, aligning with critical literacy approaches in language teaching and learning (Luke & Dooley, 2011), communication is also about critiquing and creating texts serving specific cultural and community interests, including AI-generated content (Grünewald et al., 2023, p. 1).

Given these considerations, I am interested in the challenge of incorporating digital technologies, in this case AI, in ways that transform the use of drama and picturebooks in language and literacy teaching. How can AI be combined with drama to design tasks that are previously inconceivable, tasks that capture and frame dramatic moments to provoke critical thinking and practice? With such contemplations in mind, I seek to put forward two examples of drama-AI integration using Chris Wormell’s picturebook The Big Ugly Monster and the Little Stone Rabbit (2004).

The Picturebook: The Big Ugly Monster and the Little Stone Rabbit

Chris Wormell tells the story of a monster that is so ugly that all animals and birds flee at the very sight of him. Flowers drop their petals, trees shed their leaves, and even the grass withers and dies when the monster is nearby. Left with only stones, the monster carves out some animal friends. But they all crack and shatter when he smiles, all except the little stone rabbit. The monster is happy! He sings and dances and somersaults, and the little rabbit is always there with him. Many years go by, the monster grows older and quieter. Until one day he never comes out of his cave and the stone rabbit sits alone. On this very day, the grass starts to grow, and the flowers begins to bloom.

This picturebook lends itself to be fitting material for integrating drama, AI and literacy education for multiple reasons. To begin with, it features an unusual character, the ugly monster, which we typically associate with violence and fear. According to Haynes and Murris (2012), we tend to be more absorbed and immersed in materials characterized by unusual features and exotic experiences. They argue that ‘by focusing on the extremes and limits of experience, and the bizarre and the strange, the familiar world around us seems to become more meaningful’ (Haynes & Murris, 2012, p. 140). Quality picturebooks are compared to works of art, the educational potential of which lie at the interconnection of ‘the aesthetic quality of a work of fiction, the emotions it generates, and the thoughts it provokes’ (Haynes & Murris, 2012, p. 138). This interconnection is precisely what renders this book a powerful catalyst for fostering critical literacy skills in young learners and serves as an ideal platform for merging drama and AI tools. The language is lively, even poetic, characterized by vivid imagery and a playful tone. The images, in close-up shots and full shots, complement as well as contrast the texts, provoking in the reader simultaneously a sense of anticipation and fear, of both amusement and sadness.

By adopting an omniscient voice, the narrator directly addresses the readers, inviting them to feel the monster’s absolute loneliness and sheer happiness, stirring up in us sympathetic emotions no matter how many times we read it (Haynes & Murris, 2012). It provokes questions and anticipations as the reader turns the pages, questions such as ‘Why didn’t the stone rabbit crack and shatter into rubble?’. Yet, like any skilled storyteller, Wormell deliberately leaves gaps in the narrative, inviting the reader to fill in the blanks.

Examples of Integrating Drama and AI

The following suggestions are based on Wormell’s The Big Ugly Monster and the Little Stone Rabbit. The target learners are sixth-grade ELT students, and the purpose is to enhance their critical AI literacy. The text of the picturebook has been simplified to suit the language level of the target learners while maintaining the dramatic and humorous effect (see Appendix I). These students are expected to have been learning English for at least five years, reaching a proficiency level of A2/B1. Students will explore the story from their own perspective as an interested reader, and that of the protagonist, an ugly monster. By generating prompts, they will critically examine the AI-generated images and soundtracks, considering how these outputs are shaped not only by their own textual inputs but also the data sets used by AI algorithms. Overall, the young students will engage with textual and visual signs alongside AI tools in an intermedial, creative, and critical manner.

Drama, text, and image: Creating the ugly monster

Making contrasting images. Before introducing the picturebook or showing any pictures from it, we start with one drama activity called Making contrasting images (Baldwin & Galazka, 2021, p. 60). The strategy involves students in devising two images: one depicting the moment before and the other depicting the moment after a specific dramatic event. The first five openings in the book vividly portray two contrasting scenarios before and after the arrival of the protagonist. With the repetitive use of ‘so ugly that…’, the text conveys the monster’s destructive power and his desolate situation in a humorous and dramatic way.

To conduct this drama activity, we put students into groups of four or five. Each group works with one sentence (see Appendix I) to devise two images that involve all characters in the picturebook. For instance, with sentence a), He was so ugly that all the animals and birds ran and flew away, the first image would be a happy scene of birds and animals, whereas the second would be the moment of fleeing frozen in action. We view each image as a whole group after students have prepared their images. Every group presents the first image upon the instruction of ‘Show me the moment before’ and the second image upon ‘Show me the moment after’. The students then work on their transitioning from one to the other so that it is clear and maximizes the dramatic effect.

We view the images again by groups. Upon each showing, the observing groups are encouraged to speculate about the monster’s potential features and destructive abilities based on the presented images. Finally, students are prompted to reflect how they would feel if they were the ugly monster. The teacher gathers valuable ideas regarding the monster’s appearance and emotions, noting them down on the blackboard or flip chart for future reference.

Padlet’s I can’t draw AI function: Text-to-image. Instead of drawing an ugly monster using pens or digital tools with a few descriptive sentences added (Crumpler & Schneider, 2002), students can use Padlet’s I can’t draw function to input prompts and let AI do the drawing. More specifically, we can focus on capturing the ugly monster in a particular moment, such as when the birds flee from him. Clear guidelines should be provided. For example, the image should show the setting with two or three (or more) prominent features, the monster’s emotion at that moment, and what he is doing. In addition, students can also be introduced to visual literacy concepts with regard to painting style, a character looking away from or into the camera (cinematic point of view), colour scheme, and composition considerations.

Figure 2 illustrates one image generated by AI based on a prompt that describes a sad and disappointed monster standing in front of his barren cave. We can demonstrate in Padlet how this image is created by accessing the I can’t draw function, entering the text prompt, and clicking the submit button. Multiple images will be generated and we can discuss the ones the groups like the most. It is important here to draw students’ attention to what information from the prompt is reflected in the image and what is not. For instance, the monster in the image has round, googly eyes instead of square ones as specified by the prompt. This presents an opportunity to urge students to identify similarities with other monsters from movies or picturebooks; for example, the eyes are almost identical to those of the Gruffalo! In so doing, we are introducing the mechanism of AI to the young learners and encouraging them to critically reflect upon its biased algorithm.

After the demonstration and discussion, students can begin crafting their own prompts by drawing on the content and language explored in the previous drama activity. These prompts can then be tried out with the text-to-image function on Padlet. They can share one image on the Padlet board using a similar format as in Figure 2. We can then look at a few works, inviting the creators to share their creative process and what they like and dislike about the images generated. At the end of this activity, we can compare our own works with the monster image from the book.

Discussion. Devising two contrasting images urges the students to fill the textual gap and imagine what it was like before the monster’s arrival. As individuals in the group, each participant negotiates their role in the imaging process, maintaining his or her own interpretations while contributing to a meaningful collective visual expression. In this process, the learners alternate between the textual and the visual meaning systems in a playful way. The observation of and speculation about the visual stimuli in the shared communal space adds a cognitive layer, and may bring a sense of joyful anticipation. Imagining themselves as the monster will perhaps evoke differing emotional responses, accentuating learner autonomy within a genuine communicative context as it involves various meaning systems and immerses students in a whirlwind of emotions.

Figure 2. The ugly monster generated through AI, example of a biased algorithm

As previously mentioned, writing, including drawing, plays a vital role in preparing for drama as it enables learners to negotiate their thoughts and experience into written texts (Crumpler & Schneider, 2002; Surkamp, 2012; Winston, 2013). Similarly, the simultaneously individual and collective imaginations about the monster serve as valuable resources for prompt creation, as do the language items that emerge throughout this process. The whirlwind of emotions further motivates the learners to create their own monster images with a humane touch. While drafting textual prompts in AI represents a substitution of conventional writing tasks, the images generated allow learners to observe the immediate effect of their intermedial negotiation process, though the effect may sometimes be unintended. In this manner, the integration of AI makes possible a task that was previously inconceivable and thus has a transformative potential (Puentedura, 2010).

Drama, text, and music: The happy monster with the stone rabbit

Acting out. From the ninth to the eleventh opening, the book illustrates the joyful moments shared by the ugly monster and a stone rabbit. The monster sings, dances, and somersaults, destroying everything nearby except for the rabbit, and that makes him happy. Each scene is related following an almost identical structure, and each repetition intensifies the dramatic effect of the language. Yet the accompanying images, such as the splitting rocks, cracking ground, howling wind and lashing rain, serve more as expressions of the monster’s happiness than evidence of any violence. The text and the images combine to create an aesthetic and sensational experience, the beauty of which can only be realized, I argue, by a dramatic enactment.

Acting out the text is a playful method for interpretation as it allows students to not only visualize the text’s aesthetic qualities but also expand them using their imagination and that of their peers (Surkamp, 2015). The original text is again simplified to suit the target learners’ level while preserving its rhetorical and theatrical essence (see Appendix II). Students can be put into groups of four or five, with each group assigned a specific scenario to work on. They practise speaking the text in unison and creating accompanying images and movements that involve everybody in a collective role. For example, with the first sentence, while speaking in unison ‘The monster sang’, everybody in the group forms one big monster by becoming different body parts and gestures singing. While speaking ‘and when he sang’, everyone resumes neutral position as if taking on a collective role of a narrator. And while speaking ‘rocks shattered and split for miles’, everybody becomes a different piece of rock breaking in their own unique ways.

The teacher goes around the room and previews each group’s enactment, offering advice and assistance when needed. Partner groups can be formed for presenting each group’s work. This means when one group is performing, its partner group needs to observe the performance closely. During the reflection that follows, each group can share what they like and dislike about each other’s dramatic interpretations.

Introducing the idea of ‘pathetic fallacy’ (Lodge, 2012, p. 85), which refers to how we project our emotions to the surrounding objects and nature around us, could add depth to character interpretation. To demonstrate the concept, we can ask the first group to show the rocks shattering and splitting again but in slow motion and meanwhile ask the observers to find commonalities between this shattering and splitting process and crackling fireworks in the sky. By associating the shattering rocks with fireworks, students might gain a deeper understanding of the monster’s perspective and emotions: the splitting rocks could be crackling fireworks brightening the sky for the monster. This process of enactment-observation-association is repeated with each group, and the associations are recorded for future use.

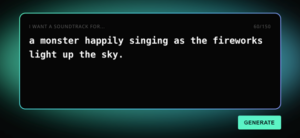

Loudly’s AI for soundtracks: Text-to-music. Music and sound are commonly used theatrical means for their power of engaging emotions and building dramatic tension. In drama classrooms, teachers use music to set the mood while reading stories or use the activity of sound collage/soundscape to suggest certain scenes or environments (Baldwin & Galazka, 2021, p. 72). To further enhance the dramatic effect of the performance above, an option could be to use the Text to music function of Loudly (an AI-powered music platform) to generate a suitable soundtrack as a group, one that captures the emotional journey and the environmental atmosphere in this part of the story.

Such visual details create a particular setting for the scene, implying a happy mood.

Figure 3. Prompt for generating music through Loudly AI

After the teacher demonstration, students can test out various prompts in Loudly, experimenting with different music parameters, going back to change the prompt and adjusting the parameters again, until they find their favourite soundtrack, copying down each prompt used and downloading the soundtrack they find appropriate in the process. A few pairs can share their creations with the class and explain the decisions they have made, prompting a discussion whether the soundtracks align with their imaginings and why or why not.

One or two soundtracks can be chosen to accompany the performance of the text. Students will return to their groups from the previous acting-out activity and rehearse their dramatizations again to the chosen music. Their work will be demonstrated and discussed again to explore the potentially different feelings and experience.

Discussion. Acting out the text requires participants to creatively represent the text through physical and vocal means. Akin to Making contrasting images, they not only need to negotiate the meaning of the text with their prior knowledge and sociocultural experience but also need to negotiate with their fellow group members in order to create a meaningful performance. By playfully embodying the text in space, that is, by turning spitting rocks and howling winds into physical representations, students directly experience the ugly monster’s awkwardness as well as his genuine happiness. Slowing down the physical representations and encouraging imaginative associations which reflect the monster’s mental state prepares students for creative language use while working with AI.

Similar to the Text-to-image function, Text-to-music AI technology also foregrounds language as action. The soundtracks generated are immediate results of using language, albeit that the results here are more versatile and their relationships to the textual prompts are harder to trace in comparison to the text-image translation. By justifying their soundtrack choices and comparing them with their imaginings, students critically reflect on the advantages and shortcomings of AI technology. In this attempt at integrating drama and AI, drama again functions as a vehicle facilitating the intermedial meaning-making process as learners draw on their dramatic experience for writing prompts. The composition of these prompts, however, also becomes part of the drama process especially when the product is used to enrich dramatic presentation. The drama experience and the associations based on their physicalization serve as valuable source for content and language in this creative process. The integration of drama and AI can empower learners to create content more confidently and critically across textual, auditory, and visual meaning systems, making it a transformative teaching practice.

Conclusion

In this article, I argue for the use of picturebooks in the classroom for the theatrical interplay of words and images, and advocate participatory drama as an ideal pedagogical realization due to its playful and social nature and its attention to the aesthetic quality of the picturebook. Furthermore, in light of recent developments in AI and the emerging concept of critical AI literacy, I contemplate the transformative opportunities combining AI and drama activities can provide when utilized for teaching literary texts.

To illustrate the potential of such integration, I explore Chris Wormell’s The Big Ugly Monster and the Little Stone Rabbit, and present two teaching activities. One activity combines Making contrasting images with Text-to-image AI function, involving learners in exploring the main character and his dilemma while reflecting on the biases inherent in both human and AI-generated imaginings of monsters. The other activity merges Acting out with Text-to-music AI function to engage the learner aesthetically in the collective creation of a dramatic performance accompanied by an AI-generated soundtrack. I suggest that participatory drama activities can be powerful catalysts for learners to engage with AI, the effective use of which depends heavily on students’ prompt-generation ability, that is, their writing competence. While drama provides a genuine context for writing, as is often argued, the use of AI makes writing tasks more authentic and motivating. The two writing/prompt-generation tasks, such as describing the rejected monster through AI and showing the monster’s happiness by associating it with surrounding objects and nature, enable learners to perceive the effect of language immediately. This motivates them to go back and forth between the textual and visual/auditory worlds to find the most suitable text-visual or text-auditory interpretation of their imagination.

Furthermore, the two integrations also demonstrate the importance of guided observation and reflection. For drama and AI to be effectively combined to achieve the purpose of fostering critical AI literacy development, we should not only focus on the doing, i.e., acting out certain scenes or generating visual/auditory products. The guided observations and reflections are critical for facilitating focused creative, communal, and critical interpretations, empowering learners to navigate the complexities of language and AI technology.

Bibliography

Wormell, Chris (2004). The Big Ugly Monster and the Little Stone Rabbit. Random House.

References

Bader, B. (1976). American picturebooks from Noah’s ark to the beast within. Macmillan Publishing Company.

Baldwin, P., & Galazka, A. (2021). Process drama for second language teaching and learning: A toolkit for developing language and life skills. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Bland, J. (2022). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350190016

Cameron, D., Anderson, M., & Wotzko, R. (2017). Drama and digital arts cultures. Bloomsbury.

Cannon, M., Bryer, T., & Hawley, S. (2023). Incorporating digital animation in a school play: Multimodal literacies, structure of feeling and resources of hope. Literacy. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12355

Carroll, J., & Cameron, D. (2009). Drama, digital pre-text and social media. RIDE: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 14(2), 295–312.

Crumpler, T., & Schneider, J. J. (2002). Writing with their whole being: A cross study analysis of children’s writing from five classrooms using process drama. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 7(1), 61–79.

Eikel-Pohen, M., & Nock, C. (2023). Improvisation activities in online language courses. Scenario, 17(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.33178/scenario.17.1.6

Haynes, J., & Murris, K. (2012). Picturebooks, pedagogy, and philosophy. Routledge.

Fanouraki, C., & Zakopoulos, V. (2023). Interacting through blogs in theatre/drama education: A Greek case study. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2023(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.775

Göksel, E., & Abraham, N. (2022). Conquering the Zoombies: Why we need drama in online settings. Scenario: A Journal for Performative Teaching, Learning, Research, 16(2), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.33178/scenario.16.2.6

Grünewald, A., Schädlich, B., & Surkamp, C. (2023). Diskussionsbeitrag der Klett-Akademie für Fremdsprachendidaktik zu KI-Tools und deren Relevanz für Schule, Unterricht und Lehrer:innenbildung. Klett Akademie für Fremdsprachendidaktik. https://www.klett.de/inhalt/sixcms/media.php/437/24_07_2023_Diskussionsbeitrag_Klett-Akademie.pdf

Kao, S., & O’Neill, C. (1998). Words into worlds: Learning a second language through process drama. Ablex.

Lodge, D. (2012). The art of fiction. Random House.

Long, D., & Magerko, B. (2020, April). What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–16). https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376727

Luke, A., & Dooley, K. T. (2011). Critical literacy and second language learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research on second language teaching and learning (pp. 856–868). Routledge.

Mourão, S. (2016). Picturebooks in the primary EFL classroom: Authentic literature for an authentic response. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 4(1), 25–43.

Nicholson, H. (Ed.). (2000). Teaching drama 11–18. Continuum.

Nilsson, M. (2023). Teachers’ scaffolding roles during picturebook read-alouds in the primary English language classroom. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 11(1), 43–67.

Puentedura, R. (2010). SAMR and TPCK: Intro to advanced practice. Hippasus. http://hippasus.com/resources/sweden2010/SAMR_TPCK_IntroToAdvancedPractice.pdf

Salisbury, M., & Styles, M. (2012). Children’s picturebooks: The art of visual storytelling. Laurence King Publishing.

Schmidt, T., & Strasser, T. (2022). Artificial intelligence in foreign language learning and teaching: A CALL for intelligent practice. Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies, 33(1), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.33675/ANGL/2022/1/14

Strasser, T., Plikat, J., & Peuschel, K. (2023, September 27–29). Herausforderungen Künstlicher Intelligenz in der Fremdsprachenlehr- und -lernforschung [Panel discussion]. 30. Kongress der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Fremdsprachenforschung, Freiburg, Germany.

Serrurier-Zucker, C., & Gobbé-Mévellec, E. (2014). The page is the stage: From picturebooks to drama with young learners. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2(2), 13–30.

Surkamp, C. (2012). Teaching Literature. In: M. Middeke, T. Müller, C. Wald, & H. Zapf (Eds.), English and American Studies (pp. 488–495). J. B. Metzler.

Surkamp, C. (2015). Playful learning with short plays. In W. Delanoy, M. Eisenmann, & F. Matz (Eds.), Learning with literature in the EFL classroom (pp. 141–156). Lang.

O’Toole, J., Stinson, M., & Moore, T. (2010). Drama and curriculum: A giant at the door. Springer.

Valente, D., & Mourão, S. (2022). Picturebooks as vehicles: Creating materials for pedagogical action. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 10(2), 1–28.

Wang, X. (2016). Introducing modernist short stories through participatory drama to Chinese students in higher education [Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick]. University of Warwick Publications service & WRAP. https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/78162/

Wiley, H. (2022, October 24). Good practices born during the pandemic and to be sustained: How the theatre sector has reinvented itself and what it wants to develop in the future [Transcript]. 8th Culture & RTBF Meeting: Co-construction in the age of digitalization, Théâtre de Namur, Belgium. https://www.europeantheatre.eu/download-attached/77UUGGwRrIPISIURuD1jpQ8fLu5wNoTBLoSlHP2RI0RH8RCm3J

Wilhelm, J. D. (2016). ‘You gotta be the book’: teaching engaged and reflective reading with adolescents. Teachers College Press.

Winston, J. (2013). Drama and English at the heart of the curriculum: Primary and middle years. Routledge.

Winston, J. (2022). Participatory drama: A pedagogy for integrating language learning and moral development. Beijing International Review of Education, 3(4), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311221089674

Zirkel, M. (2022). The potential of picturebooks in primary ELE: Fostering language skills and addressing pressing concerns of modern-day society. In T. Summer & H. Böttger (Eds), English in Primary Education: Concepts, Research, Practice (p. 117–139). Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press.

Appendix I. He was So Ugly that …

| a) He was so ugly that all the animals and birds ran and flew away. |

| b) He was so ugly that all the flowers dropped their petals and the trees shed their leaves. |

| c) He was so ugly that even the grass turned brown and withered and died. |

| d) He was so ugly that if he looked up at the blue sky on a sunny day, it would most likely turn grey and pour down rain, or even snow. |

| e) He was so ugly that if he stepped into a pond for a swim, it would instantly dry up, with a hiss of steam. |

Appendix II. The Happy Monster

| a) The monster sang.

b) And when he sang, rocks shattered and split for miles. |

| c) The monster danced.

d) And when he danced, the ground shook like an earthquake. |

| e) The monster juggled.

f) And when he juggled, lightning flashed and thunder cracked. |

| g) The monster somersaulted.

h) And when he somersaulted, the wind howled and the rain lashed down. |