| A Pedagogical Framework for North American Indigenous Multimodal Texts in English Language Teaching

Dolores Miralles-Alberola |

Download PDF |

Abstract

To include representation of Indigenous peoples in the classroom, educators should prioritize texts that are tribally specific, thoroughly researched, and authored by Indigenous writers, ensuring the language and historical narratives are accurate and respectful. This article aims to discuss such principles in the context of Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies, and their connections with social justice, whilst providing a selection of books and their affordances for an action-oriented pedagogical framework in ELT. The selection includes: the graphic novels A Girl Called Echo, written by Katherena Vermette and illustrated by Scott B. Henderson (vols 1-4, 2017-2021) and Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide (2018), with words from Isabel Quintero, illustrations by Zeque Peña and photographs from Graciela Iturbide herself; and the picturebooks Shi-shi-etko (2005) and Shin-chi’s Canoe (2008) by Nichola Campbell with illustrations by Kim LaFave, and Joy Harjo’s For a Girl Becoming (2009), illustrated by Mercedes McDonald. These multimodal books can work as text ensembles to foster deep reading and help unveil the unanswered questions other texts may leave in terms of sovereignty, memory, identity, and women’s agency, specifically of the Métis, Salish, Zapotec, and Muscogee peoples in North America.

Keywords: action-oriented approach, Indigenous critical literacy, Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies, Indigenous multimodal children’s literature, pedagogical frameworks, social justice

Dolores Miralles-Alberola (PhD) is an Assistant Professor in Education at the University of Alicante, Spain. She has focused on resistance literature, film, and Native American literature and culture. Her most recent publications deal with Indigenous children’s literature in ELT. She is a member of the research groups ACQUA and ELEI_UA.

This article was written during a research stay at Nord University (Autumn 2024), funded in part by the University of Alicante Vicerrectorado de Investigación (ACIE24-09).

Introduction

Beyond their aesthetic, cultural, and emotional value, art and literature constitute ways of self-representation granting minoritized peoples to share their knowledge(s) with other peoples and cultures. Rather than appropriating or exploiting the cultures of others, the arts emerge as a thoughtful way to approach different worldviews, histories, and philosophies. Literature, in its graphic or oral dimensions, is also an ancestral form to teach cross-culturally and from generation to generation, aligning closely with Indigenous pedagogies. Indigenous communities across North America have long used storytelling to preserve history and identity. However, Indigenous peoples’ narratives have often been marginalized in mainstream ways of representation. Crow Creek Sioux scholar, poet and professor Elizabeth Cook-Lynn points at the significance of narrative ownership, arguing that Indigenous stories must be told by Indigenous voices, as ‘Whites have told the story, which has gone from hatred to adoration, from vilification to romantization, from abuse to respect, and back again’ (Cook-Lynn, 1996, p. 63).

This article investigates how incorporating multimodal texts by Indigenous authors into English language teaching (ELT) through a critical literacy perspective can address these inequities. Multimodal children’s literature stands as a rich medium that combines visual and textual elements and the potential to address critical issues of representation, identity, and cultural memory. Proceeding from an Action-oriented Approach (AoA), and inspired by previous pedagogical frameworks, I propose the quaternity Connect Experience Question Respond (CEQR) to work with a text ensemble (Delanoy, 2018) that brings Indigenous literatures and perspectives into the classroom. The selection includes the graphic novels A Girl Called Echo (vols 1-4, 2017-21), Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide (2018), and the picturebooks Shi-shi-etko (2005), Shin-chin’s Canoe (2008) and For a Girl Becoming (2009). Incorporating Indigenous pedagogies to approach these texts meaningfully, educators can gain the adequate skills to be researchers in intercultural literature and equip students with the tools to interrogate biases, understand sociopolitical contexts, and engage in transformative actions that advance social justice.

Indigenous Knowledges and Pedagogies

The emergence of Indigenous voices in academia began in the late 1960s with the establishment of American Indian Studies and Native American Programmes in US universities (Hernández-Ávila, 2003). By the 1990s, this development reached a critical juncture, marking a breakthrough in which Indigenous peoples speak for and about themselves (Cook-Lynn, 1996, p. 80) rather than as subjects of outdated anthropological observations. Today, Indigenous scholarship constitutes a well-established and respected academic tradition. As such, we should engage with the works of Indigenous thinkers – particularly when critiquing, analyzing, or pedagogically applying Indigenous literatures and arts – to ensure that Indigenous perspectives remain central and respected in the academic discourse.

This epistemological shift is evident in the deliberate pluralization of terms such as ‘knowledges’, ‘literatures’, ‘pedagogies’, and ‘literacies’, which Indigenous scholars employ to reclaim the diversity, multiplicity, and context-specific nature of Indigenous philosophies (Battiste & Henderson, 2000; Justice, 2018; Reese, 2013; Smith, 1999). The pluralization actively challenges the Global-North paradigms that tend to universalize knowledge and the single, hierarchical worldview. Arts and literatures, on their part, constitute the most profoundly humane instruments and serve as mediums of expression for self-representation both individually and communally.

Transformative literatures

Approaching literary artefacts created by Indigenous artists is one of the most legitimate ways to learn about their communities, history, culture, demands, and worldviews. It would however be overly simplistic to confine Indigenous literatures solely to themes related to indigeneity. As Laguna Pueblo writer Leslie Marmon Silko asserts, ‘[t]he way you change human beings and human behaviour is through a change in consciousness and that can be effected only through literature, music, poetry – the arts’ (Mellas, 2006, p. 14), highlighting the transformative power of creative expression in reshaping attitudes and schemata.

Daniel Heath Justice (2018), of the Cherokee Nation, points out that Indigenous literatures teach how to be human, good relatives, good ancestors and how to live together. Literature is then a pedagogical tool, but also a way of self-exploration, as we ‘know ourselves only through stories’ (Justice, 2018, p. 34). This profound understanding of storytelling’s role demands that teachers incorporating Indigenous literatures must include Indigenous theoretical perspectives, knowledges, and pedagogies to design meaningful and respectful learning frameworks, honouring these narratives as living traditions.

Not belonging or not being versed enough in respect to Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies does not have to discourage educators from teaching with Indigenous literatures. On the contrary, they should embrace the challenge, striving for informed and thoughtful approaches, and making intelligent use of such literatures (White-Kaulaity, 2006). Furthermore, in the spirit of learning by doing, it is legitimate and creative to experience and experiment with the possibilities of Indigenous literatures in the classroom, even when being at risk of making mistakes, as long as it is done respectfully towards the teachings of Indigenous artists, scholars, and educators.

Selection principles

According to Nambé Pueblo Debbie Reese (2018), creator of the blog American Indians in Children’s Literature (AICL), Indigenous critical literacies must help ‘read between the lines and ask questions when engaging within literature: Whose story is it? Who benefits from these stories? Whose voices are not being heard?’ (p. 390). Critical Indigenous literacies centre on authenticity in the representation of Indigenous voices, narratives, and histories. Reese (2013, 2018) emphasizes the importance of tribally specific texts authored by Indigenous writers, cautioning against clichéd portrayals. Simplifying Native identities into a generic ‘Indian’ identity fosters clichés, since otherness (Said, 1978) tends to be stereotyped when seen uni-dimensionally. To challenge these biases, acknowledging the diversity among Indigenous groups is crucial. Thus, a way to tackle prejudice, when teaching a literary text, is to bring into the classroom the concrete context of the tribe(s) the author belongs to (White-Kaulaity, 2006, p. 9).

In How to Tell the Difference: A Guide to Evaluating Children’s Books for Anti-Indian Bias (Slapin et al., 2000), the California-based Native organisation Oyate provides useful guidance about the representation of Native peoples and addresses the identification of clichés, posing questions such as ‘Is there anything in this book that would embarrass or hurt a Native child?’ (Slapin et al., 2000). It is important that children should never be hurt when their cultures are represented in any type of artistic product. Other aspects addressed in the guide are tokenism, loaded words, distortion of history, standards of success, the role of women and Elders, and the background of authors and illustrators (Slapin et al., 2000). These guidelines prove useful in re-educating and decolonizing the Euro-American gaze, as ‘the larger culture needs to unlearn and rethink how the identities of Indigenous peoples are represented and taught’ (Reese, 2018, p. 390).

Cook-Lynn (1996) raises an essential statement: ‘Who gets to tell the stories is a major issue of our time’ (p. 64), which connects with representative social justice. Nancy Fraser’s (2005, 2013) model for social justice identifies three interrelated dimensions: recognition, which emphasizes respect and recognition of cultural identities; redistribution, which focuses on the equitable allocation of resources and opportunities; and representation, which promotes inclusive participation in decision-making processes. Social justice is related to critical literacy, as it involves disrupting commonplace assumptions, interrogating multiple viewpoints, and engaging with social justice to promote equity (Lewison et al., 2002). Luke (2018) extends this by advocating for dialogue and critique of texts to foster ethical imperatives for social justice, as ‘critical literacy education is premised on an ethical imperative for freedom of dialogue and the need to critique all texts, discourses, and ideologies as a means for equity and social justice’ (p. 358).

Indigenous pedagogies

Indigenous critical literacies must coexist with Indigenous pedagogies, which are personal and holistic, experiential, place-based, and intergenerational (Antoine et al., 2018). From the personal and holistic, these pedagogies emphasize the development of human beings as a whole, valuing not only academic or cognitive knowledge but also self-awareness, social development, and emotional and spiritual growth. Students can be compelled to experiment with the four dimensions of knowledge – emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and physical (Antoine et al., 2018) – both within themselves and with the world, understanding humanity in its deepest sense, encompassing all beings (Justice, 2018).

Indigenous pedagogies also stress experiential learning, where knowledge is gained through learning by doing – observation, action, reflection, and further action (Antoine et al., 2018). In this sense, all areas of teachers’ practice should engage in social justice, and educators should become action researchers (Castellon, 2017). Through the indigenization of learning, participants might develop strategies that make an impact on students’ communities and translate Indigenous knowledges into actions that change their environment. This aligns with action-oriented teaching approaches, which advocate taking what has been learned in the classroom into life and the world beyond school.

For its part, place-based learning implies knowledge that is connected to a specific location, experience, and community, grounding learning in a particular place (Antoine et al., 2018). Cook-Lynn (1996) discusses the importance of land, identity, language, and mythology, noting that tribal bonding with geography is a core element of Native nationalistic sentiment. She highlights the spiritual connection to the land, which is deeply rooted in history and mythology, both of which are essential ‘components of literature’ (p.87). Further, she argues that the origins of a people are tribal and tied to a specific geography; mythology and geography are inseparable, and even language is rooted in a specific place (p. 88).

Finally, intergenerational learning also plays a crucial role, with Elders being highly respected as teachers who pass down wisdom and knowledge to younger generations, as they are experts in Indigenous pedagogies (Antoine et al., 2018). This applies to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, who are encouraged to learn from the teachings of the older members of their own communities and should be counselled to approach them respectfully. As Indigenous literatures emphasize, such learning fosters not only personal growth but also the responsibility of being good relatives – meaning good members of the community – and becoming good ancestors (Justice, 2018).

A Pedagogical Framework to Foster Indigenous Knowledges

Building on an Action-oriented Approach (AoA) and informed by existing pedagogical models, I propose the Connect Experience Question Respond (CEQR) framework to engage with a text ensemble that centres Indigenous literatures in the classroom. Grounded in Indigenous pedagogies, the CEQR model supports educators in using these texts to cultivate awareness, critical thinking, and meaningful dialogue while honouring Indigenous knowledges and self-representations.

The AoA positions language learners primarily as social agents (Piccardo & North, 2019), engaged in collaborative, real-world projects, since only within a social context does the act of communication make full sense (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 9). Thus, the notion of task goes beyond the merely communicative, as the AoA focuses on the development of reality-based projects to be solved by situating them socially and culturally and through social actions that do not have to be exclusively and only related to language (Germain-Rutherford, 2021, p. 91) or languages. This approach integrates reception, production, and interaction, emphasizing the role of language in socialization and identity formation. The AoA proposes the co-construction of meaning through interaction and involves collaborative and purposeful tasks in the classroom, whose primary focus is not the language itself, but the action that this language frames and propitiates. Action-taking will often result in products or events such as exhibitions, posters, outings (Council of Europe, 2020, p. 27), or even, as proposed in this article, interventions in the community.

There are four pedagogical frameworks that serve as a model for the CEQR quaternity to introduce multimodal literature and intercultural awareness in the classroom: the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies by the New London Group (NLG), Housen and Yenawine’s Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), and deep reading for in-depth learning frameworks by Janice Bland and ELLiL Project Partners.

The Pedagogy of Multiliteracies includes four moves: Situated practice/experiencing, Overt instruction/conceptualizing, Critical framing/analyzing, and Transformed practice/applying (NLG, 1996; Cope & Kalantzis, 2015). Situated practice/experiencing considers immersion in experience and the utilization of available discourses, as human cognition is situated, and meanings are grounded in real-world patterns of experience. Overt instruction/conceptualizing focuses on systematic, analytic, and conscious understanding. It involves not being merely a matter of textbook discourse based on standard academic disciplines, but a knowledge process in which the learners themselves become active conceptualizers. Critical framing/analyzing consists of interpreting the social and cultural context of designs of meaning, analyzing text functions and critically interrogating the interests of participants in the communication process. Transformed practice/applying transfers into meaning-making practice, requiring the application of knowledge and understanding to the complex diversity of real-world situations. These activity types are not necessarily linear but circular and can help create scenarios and experiences that foster the acquisition of key competences through the students’ agency. In fact, through the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies, students, as meaning-makers, can co-design the activities and the process in collaboration with the teacher in what has been defined as Learning by Design, by which learning is understood as an active process of construction of meaning (Cope & Kalantzis, 2015).

The Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) model has evolved over recent decades, initially conceived by cognitive psychologist Abigail C. Housen in the late 1990s and co-developed by museum educator Philip Yenawine. VTS emerged from Housen’s Aesthetic Development Theory (2001-02), which was based on investigations on how the different degrees of exposure to art affected the viewer’s experience. Through exposure to VTS, students develop not only aesthetic thought but also critical and creative thinking. The VTS protocol establishes a series of steps: Initial visual analysis, structural analysis, and extended analysis (Yenawine, 2013). Zapata et al. (2017) adds a fourth step called ‘aesthetic response’ to support students’ affectual and embodied responses to the visuals.

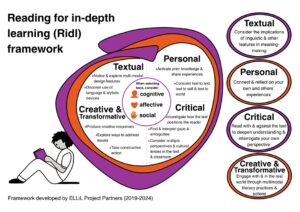

Janice Bland (2023) presents a pedagogical framework (Figure 1) based on deep reading and in-depth learning, with four interweaving steps (p. 26): Unpuzzle and Explore, Activate and Investigate, Critically Engage, and Experiment with Creative Response. Deep reading means ‘transacting with and participating actively in the literary text’ (Bland, 2023, p. 290), and fosters in-depth learning, which is understood as an approach that pursues reconnecting school learning with the world beyond school (Bland, 2023). As in the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies, learners’ agency is crucial to include ‘an active and motivated participant’ (Bland, 2023, p. 25) in the learning process.

In-depth learning and deep reading have also been pedagogically developed by ELLiL Project Partners (English Language and Literature – In-depth Learning, 2020-24) and materialized into the Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework (Figure 2), by which the activities carried out in the classroom have four different levels: Textual, Personal, Critical, and Creative and Transformative. During the Textual phase, students explore the multimodal design features and discover the use of language and stylistic devices. The Personal activates prior knowledge and connects the text with the world. Through the Critical phase, learners investigate their positioning as readers, find and interpret gaps and ambiguities, and take on a perspective through the diverse ‘cultural lenses’ in the text and the classroom. Finally, in the Creative and Transformative stage, learners produce creative responses exploring ways to address issues and take action constructively.

Figure 1. Bland’s deep reading framework (2023).

Selected Indigenous Multimodal Text Ensemble

Text ensembles introduce, as a teaching proposal, a variety of points of view by considering different texts about the same or similar themes (Delanoy, 2018). To be true to the principle of multivoicedness, a text ensemble implies it ‘must include different epistemological positions, question often unquestioned perspectives, invite critical thinking and in this way resist closure’ (Bland, 2023, p. 316). Apart from mapping a variety of North American Indigenous voices, from Manitoba in Canada to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico, in all the books selected, education plays a special role, and all contain some coming-of-age transformation.

Figure 2. ELLiL project framework.

Multimodal texts effectively promote deep engagement in multivoiced ensembles, offering a viable path forward. By incorporating visual, textual, and interactive elements, multimodality enriches learning by enabling learners to connect with content on multiple levels. Honouring Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies, multimodal storytelling reflects the interconnectedness of land, identity, language, and mythology (Cook-Lynn, 1996; White-Kaulaity, 2006; Justice, 2018).

Individually, the selected books are appropriate for different ages: the picturebooks Shi-shi-etko, Shin-chi’s Canoe, and For a Girl Becoming are suitable for 4th graders and higher primary school levels (Miralles-Alberola, 2021), whereas the graphic novels A Girl Called Echo and Photographic are addressed to secondary school students. However, while these texts and the proposed activities could work individually or assembled in diverse ways (e.g., picturebook or graphic-novel ensemble, or combined picturebook/graphic-novel ensemble), the full ensemble contained in this article would be suitable for the last stages of secondary school.

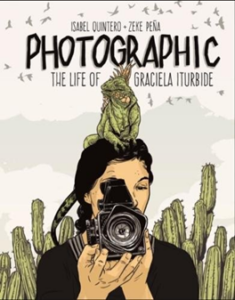

A Girl Called Echo

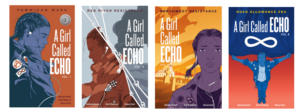

Figure 3. A Girl Called Echo graphic novel series, Highwater Press (2017-2021).

Benjamin: You are our relative. We are inside you. (…) In your blood.

It’s something we call blood memory, bone memory.

It is powerful medicine.

All we have is in you.

Echo: All you’ve been through. All your sorrow.

Benjamin: All our strength too. (Vol. 4, p 29)

This graphic novel was written by Katherena Vermette, illustrated by Scott Henderson and coloured by Donovan Yaciuk. Vermette is a Michif writer from Treaty 1 territory, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Echo contains four volumes: Pemmican Wars (2017), Red River Resistance (2018), Northwestern Resistance (2020), and Road Allowance Era (2021). The series exemplifies multimodal storytelling that connects past and present through the girl Echo, ‘a socially isolated Metis teen in what is currently called Winnipeg, Manitoba’ (Reese, 2024), dispossessed of her cultural heritage, navigating identity and history.

The visual metaphors and narrative depth in the novel help explore themes of cultural memory through education, spirituality, family, and sovereignty. As an example, note the graphic representation of the earphones on the first three covers, evocative of the hyper-connected routine of adolescents, in contrast with the last cover, which features the infinity symbol present in the Métis flag. Although Echo is constantly listening to old playlists of her absent mother, trying perhaps to connect with her at some level, the authentic connection occurs when she can finally reach her wider kin whilst inspiring her mother to investigate her ancestors.

Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi’s Canoe

Figure 4. Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi’s Canoe picturebooks, Groundwood Books (2005, 2007).

‘One, two, three, four mornings left until I go to school,’

said Shi-shi-etko as she watched

sunlight dance butterfly steps

across her mother’s sleeping face (verso, first opening).

The picturebooks Shi-shi-etko (2005) and its continuation, Shin-chi’s Canoe (2008), illustrated by Kim LaFave and written by Métis/Interior Salish author Nicola Campbell, reveal the history of the Canadian Indian residential school system, created to isolate Indigenous children from the influence of their cultures. They were separated from their parents and communities and placed in religious boarding schools. Many children went missing, never returning to their families. Such practices also took place in the United States from the beginning of the 19th century until the 1970s (Giago & Giago, 2006; Lajimodiere, 2019; Miralles-Alberola, 2022; Stout & Kipling, 2003).

Through poetic language and evocative illustrations, the books poignantly address the trauma, emphasizing resilience, memory, and the importance of family bonds. They also picture how Salish children learnt in community through contact with nature and the Elders’ teachings, exemplifying Indigenous pedagogies. Ironically, while current pedagogies in the Global North endeavour to take learners beyond the confines of the four walls, inviting them to artful and sensorial experiences, Indigenous children were historically deprived of such experiences, secluded within residential schools.

For a Girl Becoming

Figure 5. For a Girl Becoming picturebook, University of Arizona Press (2009).

Don’t forget how you started your journey from that rainbow house,

how you traveled and will travel through the mountains and valleys of

human tests (recto, sixth opening).

There are treacherous places along the way, but you can come to us.

There are lakes of theirs shimmering sadly there, but you can come to us.

And angry, jealous gods and wayward humans who will hurt you, but

you can come to us (verso, seventh opening).

For a Girl Becoming (2019), written by Joy Harjo and illustrated by Mercedes McDonald, is a visually compelling crafted work, where ancestors talk directly to a baby girl born into the community, addressing her with inspiring words. Joy Harjo is a poet, writer, musician, and a respected member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. She was the first Native to be appointed Poet Laureate of the United States, a position she held for three terms from 2019 to 2022, being the 23rd writer to receive such an honour. Harjo’s lyrical picturebook integrates Muscogee Creek traditions and poetic language to explore themes of identity and community. The spiritual undertones of the narrative reinforce the connection between past and future generations.

Community and identity provide a secure place for the little girl in an idyllic context, where she might live free from the generational trauma anticipated in Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi’s Canoe and fulfilled in A Girl Called Echo. For a Girl Becoming is an inspiring work for young readers, teaching them – and us all – to be human (Justice, 2018): ‘Feed your neighbours. Give kind words and assistance to all you meet along the way’ (Harjo & McDonald, recto, eighth opening, 2009).

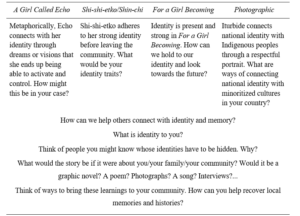

Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide

Figure 6. Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide graphic novel, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (2018).

It’s like this: when I look at a subject, the subject must always look back. Must

always agree with the shot.

That is the only way I will take a photograph. It is complicity.

We are all fragments of one another, strewn across Mexico and across borders.

Different lines in the same poem (pp. 83-85).

Isabel Quintero’s Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide (2018), illustrated by Zeque Peña, is a biographical graphic novel that bridges Indigenous and national identities through the lens of Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Themes of cultural fragmentation and reconnection are vividly portrayed through text, illustrations, and photography, offering a respectful depiction of Indigenous peoples, particularly Indigenous women. Iturbide’s iconic work, Juchitán de las Mujeres (1979-1988), which is central to the novel, stands out for highlighting the agency of Zapotec women, countering clichés of sexism often associated with Indigenous communities in Mexico. While the authors of the book are not Indigenous, their acknowledgment and celebration of Iturbide’s contributions underscore the importance of her thoughtful and empowering representations of the Zapotec and Seri peoples.

The multimodality in Photographic is multilayered, as the types of images are multimodal – combining Iturbide’s photos and illustrations – and likewise, the types of texts. The book contains captions and balloons, characteristic of comic-book language, but also texts accompanying double-paged photographs. These texts are sometimes explanatory, sometimes metaleptic – addressing the reader directly – and always poetical. Furthermore, the transgression of the narrative levels goes beyond linguistic devices, as shown on the cover, where the photographer breaks the fourth wall, pointing at the viewer with her camera.

CEQR: Connect, Experience, Question, Respond

This proposal reworks NLG, VTS, Bland, and Ridl’s pedagogical frameworks to better align with the selected text ensemble with a series of scaffolded questions and activities designed to guide educators in fostering critical observation, reflection, and action. The quaternity Connect, Experience, Question, Respond centres on Indigenous pedagogies and knowledges as foundational. Rather than providing static definitions, the CEQR pedagogical framework facilitates practicality to help teachers foster awareness and critical thinking in the classroom. For instance, guiding students to explore Echo’s identity journey can prompt discussions on acculturation and sovereignty. Similarly, exploring the linguistic devices of the poetic language in For a Girl Becoming can deepen students’ appreciation for cultural specificity and resilience, teaching them how to be better humans (Justice, 2018) through transformative literature.

Building on Zapata et al.’s (2017) assertion that non-linguistic representations ‘can serve as a valuable scaffold for negotiating content’ (p. 62), teachers can also facilitate intertextual explorations across multiple works. CEQR provides a framework where different texts can be compared and articulated. For example, students might examine the symbolic meaning of birds in both For a Girl Becoming and Photographic, analyzing how these visual elements construct meaning across different textual mediums. This comparative approach allows students to investigate semiotic representations that operate beyond linguistic systems while developing critical connections between texts.

Connect

Connecting the texts and the readers implies encouraging curiosity and taking the very materiality of the books as a starting point, fostering scaffolding for deep reading. The first and most apparent connection with the texts lies on Initial visual analysis (VTS) and visual critical literacy by questioning the images: ‘Who created this? For whom? Who benefits from its message?’ (Serafini, 2022). Students connect with books they can touch, open, and scan for information. Multimodality and the different parts of the novels and picturebooks are a language in themselves, and exploring the format may ignite the further exploration of cross-cultural contents and feminist perspectives (Allen, 1986, 1993; Fraser, 2005, 2013) to promote access to memory and identity through interaction with the texts. Furthermore, approaching the text formats, images and materiality, and the paratextual information, provides linguistic – coinciding with the Ridl Textual phase – and content scaffolding for students to approach the books and their construction of language.

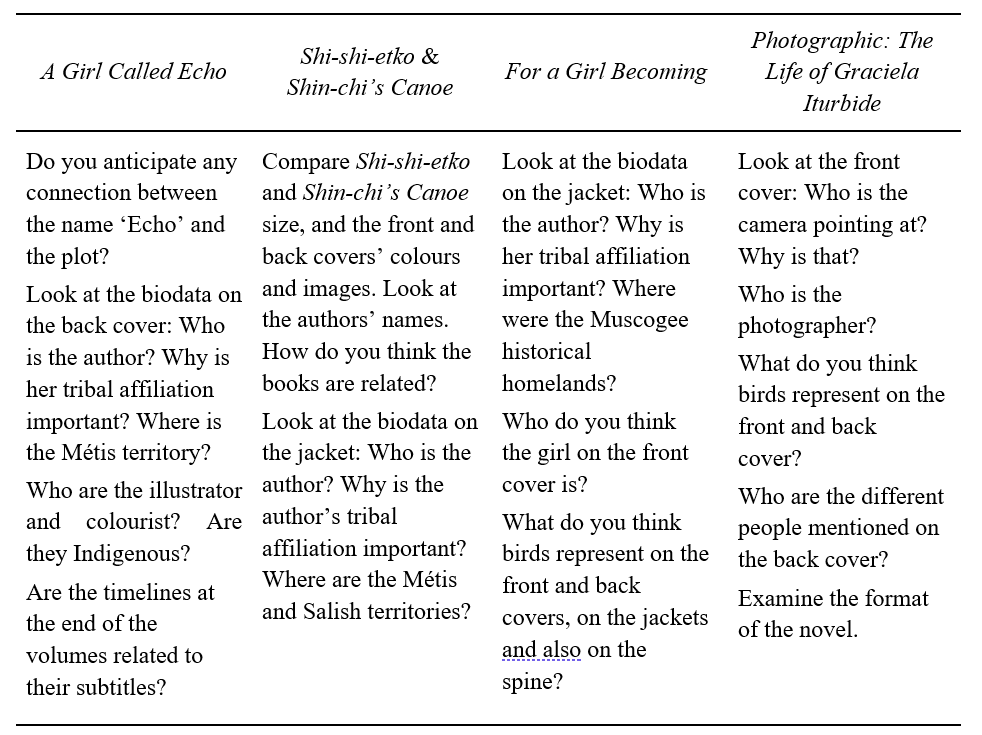

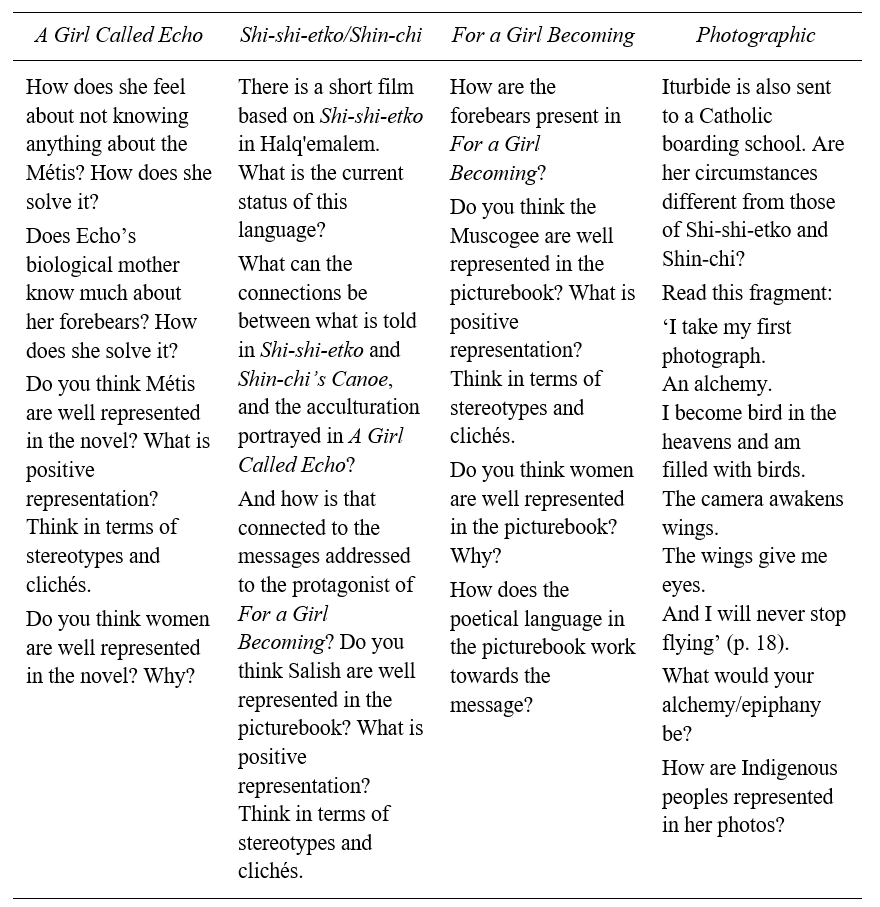

Table 1. Pedagogical framework: Connect.

Experience

Experience builds mainly upon Overt instruction/conceptualising (NLG), Ridl’s Textual and Personal, and Bland’s Activate and Investigate. Students are encouraged to do research on the proposed questions and activities. Through experiential learning (Antoine et al., 2018), and by leveraging prior knowledge and promoting information literacy and learning by doing, we may foster critical inquiry on aspects such as reflecting on female family members’ teachings and sorority, as well as revising ethnic backgrounds and their implications. whether a majority culture or a minoritized one. At this point, it is also paramount to focus on redistributive social justice from feminist and cultural/ethnic perspectives (Allen, 1987, 1993; Fraser, 2005, 2013).

Table 2. Pedagogical framework: Experience.

Question

To question is to think critically, also about personal beliefs, as the previous frameworks underline, even in the titles of the third phase: Critical framing/analysing (NLG), Critically Engage (Bland), Critical (Ridl). To discuss bias and hidden interests in themes and hints that are present in the multimodal texts and picturebooks, we must question the messages of mainstream culture on Indigenous themes, fostering criticality. By promoting the identification of themes and hints that appear in the books, related to history and the erasure of the memory of colonized peoples, we will be raising awareness on representative social justice (Fraser, 2005, 2013).

Table 3. Pedagogical framework: Question.

Respond

The mentor texts selected can serve as catalysts for transformative learning when paired with creative and applied practices. Drawing on the NLG’s concept of Transformed practice/applying, students move beyond passive consumption of texts by reinterpreting them. Also, Bland’s emphasis on experimenting with creative responses and Ridl’s notion of the transformative underscore how these creative acts can shift perspectives, fostering both self-discovery and social awareness.

To respond means to promote the creation of artifacts and/or events – abstract or concrete, through materiality or thought, images and/or words – figuring out ways to understand identity and give back to the community, contributing to the recovery of collective memory, helping students find ways to prompt recognitive social justice. This approach extends beyond the classroom, turning creative expression into actionable solidarity. Indigenous literacies model how knowledge is relational, inviting students to consider their role in broader networks of community and land, avoiding cultural appropriation in the representation of Indigenousness, and applying instead what they have learnt and investigated to their own environments.

Action-taking is a crucial component of language learning (Mourão et al., 2022). By fostering action-taking, projects may trigger creative ways to connect with the community, including themes related to ecology, community, ancestry, etc. Indigenous literatures can, in this way, teach students to investigate their own kin, reflect on identity, and nurture both personal and collective transformation.

Table 4. Pedagogical framework: Respond.

Final Considerations

This article has explored the integration of Indigenous multimodal texts within educational frameworks to promote social justice through critical literacy, emphasizing the role of representation, narrative ownership, and the importance of an Indigenous approach to pedagogy when integrating Indigenous literatures in English language teaching. Multimodal Indigenous texts present educators with both significant opportunities and unique challenges. While these texts offer rich avenues for student engagement, teachers must address obstacles such as limited qualifications in Indigenous knowledges and resistance to using these narratives. Professional development and the inclusion of diverse, high-quality texts are crucial for overcoming these barriers and ensuring the meaningful integration of Indigenous perspectives. To that end, the model CEQR focuses on learning from Indigenous knowledges, avoiding cultural appropriation, misrepresentation, and/or internalization of stereotypes, applying new knowledge to local contexts and the recovering of identities and memory.

Incorporating Indigenous multimodal texts in education is a transformative step toward advancing social justice. By prioritizing authentic representation, leveraging multimodal materials, and fostering critical literacy, educators can create inclusive learning environments that honour Indigenous voices and histories. Experimenting with Indigenous pedagogies and sharing this knowledge within our current multicultural contexts further supports the indigenization of educational practices, translating these into actions that work towards the healthy functioning of our own communities. This approach may enrich learning experiences, empower students to become agents of equity and change, and promote a broader understanding of diverse worldviews and their own closer environments.

Ultimately, employing the concepts of deep reading and action-oriented teaching and suggesting the CEQR pedagogical framework to adapt previous frameworks to a more appropriate structure in accordance with Indigenous perspectives, this article has examined how these types of text ensembles can empower student teachers to critically engage with Indigenous histories and identities, fostering equity and inclusivity in classrooms and beyond. These efforts – which need further exploring and research – highlight the importance of embracing Indigenous pedagogies to reimagine education as a tool for social justice, inclusivity, and equity in our interconnected global community.

Bibliography

Campbell, Nicola I., illus. Kim LaFave. (2005). Shi-shi-etko. Groundwood Books.

Campbell, Nicola I, illus. Kim LaFave. (2007). Shin-chi’s Canoe. Groundwood Books.

Harjo, Joy, illus. Mercedes McDonald. (2009). For a Girl Becoming. University of Arizona Press.

Quintero, Isabel, illus. Zeke Peña (2018). Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide. J. Paul Getty Museum Los Angeles.

Vermette, Katherena, illus. Scott B. Henderson & Donovan Yaciuk (2017). A Girl Called Echo: Pemmican Wars. Vol. 1. Highwater Press.

Vermette, Katherena, illus. Scott B. Henderson & Donovan Yaciuk (2018). A Girl Called Echo: Red River Resistance. Vol. 2. Highwater Press.

Vermette, Katherena, illus. Scott B. Henderson & Donovan Yaciuk (2020). A Girl Called Echo: Northwest Resistance. Vol. 3. Highwater Press.

Vermette, Katherena, illus. Scott B. Henderson & Donovan Yaciuk (2021). A Girl Called Echo: Road Allowance Era. Vol. 4. Highwater Press.

References

Allen, P. G. (1986). The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the feminine in American Indian traditions. Beacon Press.

Allen, P. G. (1993). Teaching American Indian women’s literature. In P. G. Allen (Ed.), Studies in American Indian literature: Critical essays and course designs (pp. 134–144). The Modern Language Association.

Antoine, A., Mason, R., Palahicky, S., & Rodriguez de France, C. (2018). Pulling together: A guide for Indigenization of post-secondary institutions. A professional learning series. BC Campus. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/

Battiste, M., & Henderson, J. (Sákéj) Y. (2000). Protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: A global challenge. UBC Press; Purich Publishing. https://doi.org/10.59962/9781895830439

Bland, J. (2023). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality, and critical literacy. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350190016

Castellon, A. (2017, May 28). A call to personal research: Indigenizing your curriculum. Adrienne Castellon Assistant Professor.

https://www.academia.edu/39667268/A_Call_to_Personal_Research_Indigenizing_Your_Curriculum

Cook-Lynn, E. (1996). Why I can’t read Wallace Stegner and other essays. The University of Wisconsin Press. https://doi.org/10.3368/151447

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2015). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Learning by design. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137539724

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment—Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing. https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages

Delanoy, W. (2018). Literature in language education: Challenges for theory building. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8–18-year-olds (pp. 141–157). Bloomsbury Academic.

ELLiL Project Partners. (2023). Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework. https://site.nord.no/ellil/reading-for-in-depth-learning/

Fraser, N. (2005). Mapping the feminist imagination: From redistribution to recognition to representation. Constellations, 12(3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1351-0487.2005.00418.x

Fraser, N. (2013). Fortunes of feminism: From state-managed capitalism to neoliberal crisis. Verso.

Germain-Rutherford, A. (2021). Action-oriented approaches: Being at the heart of the action. In T. Beaven, & F. Rosell-Aguilar (Eds.), Innovative language pedagogy report (pp. 91–96). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2021.50.1241

Giago, Tim, illus. Denise Giago (2006). Children left behind: The dark legacy of mission boarding schools. Clear Light Publishing.

Hernández-Ávila, I. (2003). On the Nature and Reason for Native American Studies in the Academy. Brújula: revista interdisciplinaria sobre estudios latinoamericanos. 2(1), 43-56.

Housen, A. C. (2001-02) Æsthetic thought, critical thinking and transfer. Arts and Learning Research Journal. 18(1), 99–131.

ICEPELL Consortium (Eds.) (2022). The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning. CETAPS, NOVA FCSH. https://icepell.eu/

Justice, D. H. (2018). Why Indigenous literatures matter. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. https://doi.org/10.51644/9781771121774

Lajimodiere, D. K. (2019). Stringing rosaries: The history, the unforgivable, and the healing of Northern Plain American Indian boarding school survivors. North Dakota State University Press.

Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382–392. https://doi.org/10.58680/la2002255

Luke, A. (2018). Regrounding critical literacy: Representation, facts, and reality. In D. Alvermann, N. J. Unrau, M. Sailors, & R. B. Ruddell (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of literacy (pp. 349–361). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315110592-21

Mellas, L. (2006). Memory and promise: Leslie Marmon Silko’s story. Mirage, 10(16), 10–15.

Miralles-Alberola, D. (2021). Native American children’s literature in the English language education classroom. In A. M. Brígido-Corachán (Ed.), Indigenizing the classroom: Engaging Native American/First Nations literature and culture in non-Native settings (pp. 127–145). Publicacions de la Universitat de València.

Miralles-Alberola, D. (2022). Storytelling projects on Native American children’s literature for primary English education: A case study. Children’s Literature in English Language Education. Special Issue for CLELE 10th Anniversary: Children’s Literature as Intercultural Catalyst in English Language Education 10(2), 74–97. https://clelejournal.org/article-4-2/

Mourão, S., Kik, N., & Gonçalves Matos, A. (2022). From culture to intercultural citizenship education. In ICEPELL Consortium (Ed.), The ICEGuide: A handbook for intercultural citizenship education through picturebooks in early English language learning (pp. 22–29). CETAPS: FCSH Universidade Nova de Lisboa. https://icepell.eu/docs/ICEGuide_digital.pdf

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–93. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

Piccardo, E., & North, B. (2019). The action-oriented approach: A dynamic vision of language education. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788924351

Reese, D. (2013). Critical Indigenous literacies. In J. Larson, & J. Marsh (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of early childhood literacy (pp. 251–263). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446247518.n14

Reese, D. (2018). Critical Indigenous literacies: Selecting and using children’s books about Indigenous peoples. Language Arts, 95(6), 389–393. https://doi.org/10.58680/la201829686

Reese, D. (2024, February 8). Highly recommended: A Girl Called Echo OMNIBUS. American Indians in children’s literature. https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2024/02/highly-recommended-girl-called-echo.html

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Serafini, F. (2022). Visual literacy strategies: K–12 classroom. Teachers College Press.

Slapin, B., Seale, D., & Gonzales, R. (2000). How to tell the difference: A guide to evaluating children’s books for anti-Indian bias. Oyate.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. University of Otago Press.

Stout, M. D., & Kipling, G. (2003). Aboriginal people, resilience and the residential school legacy. Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

White-Kaulaity, M. (2006). The voices of power and the power of voice: Teaching with Native American literature. The ALAN Review, 34(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.21061/alan.v34i1.a.2

Yenawine, P. (2013) Visual thinking strategies: Using art to deepen learning across school disciplines. Cambridge.

Zapata, A., Fugit, M., & Moss, D. (2017). Awakening socially just mindsets through visual thinking strategies and diverse picturebooks. Journal of Children’s Literature, 43(2), 62–69.