|

Every Story Tells a Story That Has Already Been Told: Intertextuality and Intermediality in Philip Pullman’s Spring-Heeled Jack and in Kevin Brooks’ iBoy MIchael C. Prusse |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Training English teachers involves acquainting them with suitable texts for their future classrooms. Ideally such texts touch upon matters that children and young adults respond to and such literature also offers learning opportunities both for the pre-service teachers and their students. It can be argued that such learning opportunities can be found when analysing superheroes, when considering the impact of the new media on young people or when focusing on the blending of different genres and texts. The two novels selected for this purpose are Philip Pullman’s Spring-Heeled Jack (1989) and Kevin Brooks’ iBoy (2010). The former is a hybrid of a traditional and a graphic novel and resorts to intertextual allusions, for instance by means of quotes at the beginning of each chapter. The latter text also resorts to quotations – but from different sources, namely almost exclusively from the worldwide web. While iBoy may at first sight look rather conventional as a novel, it nevertheless reveals its provenance from the digital age in the numbering of the chapters in the binary system. Young readers (and their teachers) may thus discover the pleasures of literary reading when following Pullman’s superhero (taken from a Victorian penny-dreadful) across London. Brooks’ hybrid protagonist, by contrast, a first-person narrator, allows readers to gain insights into the problematic side of his role and his powers. Ultimately these rather conventional novels succeed in capturing their readers’ attention and somewhat contradict critics who predict the arrival of a more hypertextual approach to reading because of the impact of the new media.

Keywords: intertextuality, intermediality, literary adaptation, literary appropriation, superhero [End of Page 1]

Michael C. Prusse (PhD) is Professor of English Literature and Head of Vocational Teacher Education at the Zurich University of Teacher Education. Prusse teaches courses such as ELT Methodology and English Literature for teachers at lower and upper secondary level. His research interests include postcolonial literature, the twentieth-century short story, and children’s and young adult literature.

Introduction

‘Books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told’ (Eco, 1984, p. xxiv). This insight that Umberto Eco shares with his readers in his Postscript to the Name of the Rose describes some of the most basic and pervasive characteristics of narrative. When it comes to the exploring of literature in the classroom this essential nature of storytelling does not feature prominently on most teachers’ agendas. And yet, the fact that stories are not necessarily original but adaptations or appropriations of previous stories is not entirely novel. A prominent example is William Shakespeare who used existing and suitable stories as sources when writing his plays and transformed them into his own material. The practice of mining older stories by authors can easily be traced even further back to Greek mythology and Greek drama, as Marie-Laure Ryan points out (2011, p. 1). In recent years critics have shown increasing interest in adaptation within literature but also across media. Two studies by Linda Hutcheon and Julie Sanders, which coincidentally were both published in 2006, provide some evidence for this trend. This intensified concern of critics is simply an expression of what – according to Eco – storytellers have always known, namely that it is almost impossible to be original. The persistent Romantic mythology ‘of original creation and of the originating creative genius’, vociferously proclaimed by the key protagonists of the Romantic age such as Wordsworth or Shelley, has contributed to a widespread perception of adaptations as second-class (see Hutcheon, 2006, p. 4). As a matter of fact, an adaptation may be rated more highly than the original text, as the example of Shakespeare yet again demonstrates. While Hamlet (1603) is part of the literary canon, Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (1591), one of its antecedents, is nowadays hardly known outside English departments that teach Elizabethan drama. Nevertheless, the Romantic concept of the poetic genius obstinately resides in the [End of Page 2] minds of many a contemporary reader, a state of affairs that possibly provoked Philip Pullman into claiming that writers are thieves: ‘Storytellers always steal their stories, every story has been told before’ (Lacey, 2012). Furthermore, as every reader must know, it is only the memory of previous stories that allows him or her ‘to experience difference as well as similarity’ (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 22) – in other words: if readers did not have a bank of stories at their disposal in their memories they would not be able to appreciate a new story that they encounter.

The intertextual and increasingly intermedial nature of most stories can also be illustrated by referring to two exemplary but certainly not unique texts in children’s and young adult literature, namely Spring-Heeled Jack (1989) by Philip Pullman and iBoy (2010) by Kevin Brooks. These two narratives have been selected because they are arguably suitable both for the teaching of pre-service teachers at universities of teacher education and for the actual use with students in EFL classrooms. The education of English teachers entails familiarizing them with appropriate texts for their prospective classrooms. Unfortunately, there exist rigid time constraints in most university syllabi and, hence, the texts need to serve a double purpose: in the short amount of time available, they have to address issues that children and young adults will respond to, but they should also appeal to pre-service teachers and provide sufficient justification for literary analysis. When investigating these narratives both pre-service teachers and students will inevitably be confronted with their intertextual and intermedial nature – the latter aspect is particularly relevant in a time when the number of so-called digital natives is steadily on the increase and the practices of the digital age actually shed new light on activities such as copying, adapting, retelling or sharing narrative sources. In this context it is relevant that learners become familiar with traditions of adaptation, appropriation and palimpsest texts.

Before inspecting these two books more closely, it is necessary to add one further reason for their inclusion in the curriculum of children’s and young adult fiction at the Zurich University of Teacher Education. Apart from offering well-written, exciting storylines, the most decisive factor for their selection was the phenomenon of male aversion to reading, which, in the Canton of Zurich, is particularly manifest among the lower strata of pupils at secondary school. These young men often come from families [End of Page 3] with no tradition of reading – a condition that is also described by Stephen Krashen in his analysis of the situation in the United States (see Krashen, 2004, pp. 57-58). It is with a view to entice teenage boys into reading that the novels were chosen, since they display several features that should appeal to adolescent male readers (but not exclusively to them). The two narratives both rely on superheroes to save the day, contain scenes full of action and excitement and, moreover, they allude to various genres, in particular to popular and adventure literature and thus afford a wealth of opportunities to acquaint learners with the repetitive and adaptive nature of fiction.

(Super-) Heroes

It is evident that teenagers are at a stage of their lives in which they are confronted with numerous changes, challenges, and often troubling adaptations to new circumstances. Hence, the appeal of superheroes for young male readers may be explained with a predilection for (escapist) fantasy in view of difficult and sometimes even dire personal circumstances. The two books under discussion offer very different outlooks on superheroes. Pullman’s Spring-Heeled Jack concentrates on three children, two girls and one boy, who escape from an orphanage in Victorian London with a valuable locket as their only possession. Their aim is to escape to America but they almost immediately are beset by criminals and have to hide from the police and the superintendent of the orphanage who are on the lookout for them. The appearance of the superhero and the efforts of several other helpers succeed in delivering them from a number of dangerous situations and eventually in reuniting them with their lost father who then takes them to America. iBoy, by contrast, provides ample insights into the mind of a reluctant teenage superhero and his ethical struggling about using, abusing, or not using his special powers.

The concept of the hero is – as Jones and Watkins assert – problematic, and yet it also fulfils a deeply felt need, since readers love heroes (of course, heroes also feature in oral storytelling and in other media, for instance, film). The problematic aspects can be briefly summarized with the ideological frameworks that often define heroes, namely gender, imperialism and national identity (Jones & Watkins, 2000, p. 4). Traditionally [End of Page 4] heroes rather than heroines dominate the diverse narratives forms and feminist criticism has frequently pointed out that the superhero is a specifically male concept.[i] Moreover, since certain critics assume that we live in a post-heroic age, heroes merely exist – from their point of view – ‘for debunking and deconstructing’ (Jones & Watkins, 2000, p. 1). Their pervasive presence in narrative across time and cultures has led Joseph Campbell to distil typical structures of a hero’s development, which he claims to be universal. In a nutshell, the concept Campbell labelled as ‘monomyth’ encompasses a magnified version of ‘the formula represented in the rites of passage: separation-initiation-return’ (2004, p. 28). With regard to the two novels, Pullman’s superhero does not fit this pattern for the simple reason that readers do not learn enough about his background: Spring-Heeled Jack’s aura relies on the element of surprise in his vigilante activities – and this surprise is sprung upon the reader as it is on the protagonists. For Pullman the true heroes of the novel are the three children – as Kimberley Reynolds writes about The Dark Materials, ‘growing up is the ultimate adventure in Pullman’s books’ (2006, p. 193). The superhero features as just one more character that helps them on their quest to escape from London. The story of Tom Harvey, the protagonist of iBoy, on the other hand, perfectly fits in Campbell’s basic pattern of an initiation into the world of the hero. While the pattern of ‘the hero’s journey’ (as Vogler, 1998, calls it) can indeed be perceived in countless stories, novels, and films (in particular those that originate from Hollywood), its universality may be a point of debate. And yet, the frequent recurrence of such plot constellations in many cultures makes a transfer into the classroom feasible: students may grasp and appreciate some of the key principles in the construction of plot. Moreover, they gain a deeper insight into the role and function of heroes – and learn to look critically at the problematic aspects that some heroes in popular and adventure fiction or films display.

In his pioneering study of superheroes in a range of graphic novels, Richard Reynolds (1997) has listed some of the prevalent features that their protagonists have in common. The first point he mentions is that superheroes are mostly orphans or miss at least one parent. Pullman clearly agrees with Reynolds because he provided the following statement in an interview in which he alludes to Jane Austen’s famous opening sentence of Pride and Prejudice: ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that young protagonists in [End of Page 5] search of adventure must ditch their parents’ (Fried, 2003). The novelist does not refer to superheroes but extends Reynolds’ principle to cover the protagonists of children’s literature in general where, by all accounts, the number of orphans is disproportionally large. The second characteristic of superheroes, according to Reynolds, refers to their extraordinary powers. Thirdly, justice is usually more important to them than the law (and thus they are prepared to act outside the law). Fourthly, they are virtually invulnerable and a set piece (also to be found in iBoy, 2010, p. 116) is a scene showing the surprise when a villain attempts to stick a knife into the superhero – and fails. The fifth point from Reynolds’ list refers to the superhero’s double identity – in one he is the hero with extraordinary powers, in the other he is an ordinary teenager who keeps his alter ego secret. Superheroes often wear a mask or some other form of disguise when in their superhero mode. While the mask is also part of Spring-Heeled Jack’s aura, all the other features, including a rather distinct disguise, apply to the protagonist of iBoy. Learners may thus transfer their knowledge from graphic novels such as Superman, Batman or Spiderman or their movie adaptations to iBoy and identify the various common features as well as the differences between comic book, graphic novel, movie adaptation and Brooks’s novel. Ultimately, Jones and Watkins argue that the prevalence of heroes, heroism and the popular success of fiction featuring them, justifies their existence, concluding that there would be a need to invent heroes and heroism if they did not already exist (2000, p. 12).

Literature as Part of Intermedial Culture

A further feature that lends itself for classroom usage already mentioned above is the fact that Spring-Heeled Jack and iBoy brim with allusions, adaptations (that signal a relationship with a source text or original), and appropriations (that ‘are not always as clearly signalled or acknowledged’, Sanders, 2006, p. 26). Thus, these two novels speak in multi-modal and multi-medial ways to their readers. Literature in general but intermedial literature specifically, succeeds, as Ansgar Nünning and Jan Rupp (2011, p. 30) argue, in integrating diverse discourses and in merging or contrasting the knowledge of human endeavour in widely disparate fields in such a fashion that readers may gain new and frequently critical insights as a result of perusing such texts. Moreover, by doing so, [End of Page 6] authors provide access to such knowledge to readers with a different background and they also contribute to archiving contemporary culture as well as to re-canonizing selected aspects of it (Nünning & Rupp, 2011, p. 30). Werner Wolf even proposes that literature can function ‘as an interface for all other media, and, owing to the flexibility of its verbal medium, it can do so in a more detailed manner than any other medium’ (2011, p. 8). This is, of course, the position of the literary critic, who would claim that literary criticism no longer focuses exclusively on literary texts but on fictional narratives across the media (Nünning & Rupp, 2011, p. 16).

In Spring-Heeled Jack the blending of a graphic novel with a conventional novel creates what Kimberley Reynolds calls a hybrid,

for each page combines paragraphs of text with comic-strip frames which are integral to the story. It is important to distinguish these frames from illustrations, for they do not simply show what the text has described, but they also advance the plot and contain elements of the written text (1994, p. 66).

According to Pullman, the writing process is similar for a traditional novel and for a hybrid novel – with regard to the pictures he would provide the illustrator with a description ‘in the same way one would do stage directions for a play’ (Carter, 1999, p. 191). Pullman himself is very much in favour of graphic novels: ‘This graphic vocabulary is so natural-seeming, intuitive, reader-friendly, that it seems to come to the understanding of most of us very early in our reading’ (Pullman, 1998b, p. 112). The advantages of such a blending of graphic and conventional novel are clearly the possibility for the writer to profit from the strengths of both traditional forms in the telling of a story – the graphic parts for showing (mimesis), the narrative prose for telling (diegesis). An analysis of Spring-Heeled Jack in the classroom may thus lead to learners being able to distinguish between these two essential narrative modes. Last but not least, Pullman’s Spring-Heeled Jack, illustrated by David Mostyn, abounds in cheeky asides and running gags such as animals of all sizes that observe and comment on the events – a metanarrative feature that has delighted many of its readers. [End of Page 7]

iBoy, by contrast, may at first glimpse look rather conventional as a novel but soon reveals its provenance from the digital age by means of numbering its chapters in binary code. Moreover, with its frequent references to and quotes from the worldwide web, in particular with regard to the functions of the iPhone 3GS and its manifold technical possibilities, the novel alludes to hypertext, various forms of new media, as well as to movies and graphic novels. One of the problems of a text like iBoy is, as Alison Waller points out, the fact that the rapid progress of technological development results in the novel being somewhat dated even at the moment of publication (2012, p. 104). This can also be seen as an advantage because – as with the longer perspective of a historical novel – it may be used to demonstrate to teenagers how quickly circumstances may change and how short-lived some technological advances are before they are surpassed by the next innovation. Only the test of time will show if iBoy becomes part of the canon of young adult fiction (regardless of its fixed setting at a specific point of the twenty-first century). This awareness of rapid evolution and technology being constantly outmoded by new developments is another example of a learning opportunity for pre-service teachers and students in their classrooms. Furthermore, when they encounter a diversity of texts and media that have influenced the two novels under discussion, the basic and admittedly simple assumption is that pre-service teachers and secondary school students can relate to such an approach. They will, of course, register those influences that they are themselves familiar with. Lecturers and teachers can then supplement these findings by helping them to discover more or by directly pointing out specific instances of adaptation or appropriation to them. A theoretical framework that outlines the various manners in which narratives and other media interact may lead to a more focused analysis. The phenomena of media change (e.g. film adaptations of novels), media combination (Hans-Heino Ewers coined the term ‘multi-media system offers’ referring to film releases combined with video games and merchandising, etc.) or intermedial reference (the text refers to a TV series or a film) could thus be introduced to the learners in order to help them with categorizing their reading of the texts (Nünning & Rupp, 2011, p. 14; Ewers, 2005). In iBoy, for instance, there are constant intermedial references to fictitious products from other media, which are contrasted to the ‘real life’ of the characters in the novel. When the protagonist is cornered at the end, he discusses the situation with his evil antagonist, and tells him, ‘if this was a [End of Page 8] James Bond movie, this would be the perfect moment for the mad super-villain to show Bond how clever he is by unnecessarily explaining everything to him’ (2010, p. 253). His opponent drily answers that ‘[r]eal life ain’t the movies’ (2010, p. 253). Essentially, the issue with teaching Spring-Heeled Jack and iBoy to pre-service teachers at the Zurich University of Teacher Education has a lot to do with allowing students to pursue individual paths (based on individual experiences and familiarity with different media products) and getting them to share their insights and then widen their horizons by means of additional inputs.

Spring-Heeled Jack

Right from the beginning of his book, Pullman shares the information with his readers that his narrative is based on another story by giving a short account of the legend of Spring-Heeled Jack:

In Victorian times, before Superman and Batman had been heard of, there was another hero who used to go around rescuing people and catching criminals.

This was Spring-Heeled Jack.

No one knew what his real name was; all they knew was that he was dressed like the devil, that he could leap over houses with the help of springs in the heels of his boots, and that any evildoer who came up against him met a very unpleasant end. (Pullman, 1991, p. 3; this edition henceforth SHJ)

However, it must be highlighted that Pullman actually deconstructs the Victorian legend, in which Spring-Heeled Jack was a dubious character or at least an ambivalent figure, also known to attack innocent people. The original character of Spring-Heeled Jack is revealed on the covers of various editions of Victorian Penny Dreadful magazines that feature some of his adventures and sport subtitles such as ‘The terror of London’. Furthermore, these covers frequently show a sinister bat-like figure jumping out from a hiding place and looking as if he is about to attack the people in the foreground. Captions such as ‘Man or Fiend’ illustrate the reservation that readers ought to feel about the true character of Spring-Heeled Jack. Pullman chose to change the personality of this Victorian model and transformed him into a superhero that still looks like the devil but now is intent on [End of Page 9] protecting the innocent (see also Bobby, 2012, p. 77). The author was possibly motivated to perform this transformation because he believes that creating villains is easy: ‘It’s much harder to create a hero who’s both attractive and interesting’ (Pullman, 1998b, p. 119). When Spring-Heeled Jack makes his first appearance in the story, the girls hear ‘a troubling rumble of thunder’ trundling across the sky and when the ‘wisps of fog’ are ‘whisked aside’ they see a black figure with bat-like wings, a top hat and gleaming eyes (SHJ, p. 13). The ensuing address is an ironic allusion to the annunciation to the shepherds of Bethlehem: ‘Fear not! I’m not the devil – I’m Spring-Heeled Jack’ (SHJ, p. 15). The well-known passage in the Bible reads: ‘And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people’ (Luke 2:10). Pullman’s outspoken reservations about the church are familiar to readers of his trilogy His Dark Materials, and have gained wider currency in the wake of the controversy that surrounded the filming of the first book as The Golden Compass (Weitz & Fonte, 2007). The Catholic Church protested vigorously against the way Christianity and the church were (originally) portrayed in the movie; apparently, the film was subsequently ‘sanitized’ to appease church authorities (Gorski, 2007). With this knowledge in mind, it must be assumed that Pullman very much intended the irony of this particular allusion to Luke.

Spring-Heeled Jack is narrated from multiple perspectives – readers get, first and foremost, the perspective of the children Rose, Lily and Little Ned Summers; then they also get the perspective of Mack the Knife, of Filthy and of the latter’s bad conscience in the shape of a fluttering moth that only he himself can see.[ii] It would be simple to continue in this fashion and mention more narrative perspectives. Interestingly enough, the perspective of the superhero, Spring-Heeled Jack himself, is missing. Thus, from the point of view of narrative perspective, Spring-Heeled Jack is unusual and not typical of the superhero genre. Students will immediately become aware of the multiperspectivity of the narrative and, hence, they may be introduced to such concepts as ‘the narrator’ and ‘point of view’. [End of Page 10]

The novel’s main and obvious distinction lies in the fact that Pullman joyfully participates in what Hutcheon describes as Western culture’s ‘long and happy history of borrowing and stealing, or more accurately, sharing stories’ (2006, p.4). It is this ‘sense of play’, in particular the ‘interplay of expectation and surprise’ that can provide readers with pleasure (Sanders, 2006, p. 25). At the end of the adaptation of his own novel, Count Karlstein, into an illustrated version – a similar blend of graphic and traditional novel as Spring-Heeled Jack – Pullman provides a list of works ‘consulted and ideas stolen from’ (1998a, p. 108). Such a list is missing at the end of Spring-Heeled Jack and therefore, in the following, there is a selection from the many stories that Pullman has plundered and which could be discovered by pre-service teachers or students at school. The novelist takes, for instance, characters from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728) and Bertold Brecht’s Three Penny Opera (1928) and uses them for his own purposes. Whereas Mack the Knife is a direct borrowing from the Three Penny Opera and Filthy is most probably an ironic allusion to Gay’s Filch, Polly Peachum, Macheath’s lover in The Beggar’s Opera, is turned into Polly Pickles, a barmaid in a pub who is in love with the sailor Jim Bowling rather than Macheath. One minor character, Simon who sells pies, alludes to one of the villains from the Batman universe, Simon the Pieman. At the same time, both characters allude back to the nursery rhyme of Simple Simon who wants to taste the pieman’s pies but lacks the money to buy any:

Simple Simon met a pieman,

Going to the fair;

Says Simple Simon to the pieman,

Let me taste your ware.

Says the pieman to Simple Simon,

Show me first your penny;

Says Simple Simon to the pieman,

Indeed I have not any. (traditional)

The author also names another minor character after a character from his first children’s book: the name of the organ grinder, Antonio Rolipolio, is one of the pseudonyms of Doctor Cadaverezzi in Count Karlstein – jam roly-poly, the root of [End of Page 11] Antonio’s surname is, of course, a traditional British pudding that also provides the name for Roald Dahl’s Roly-Poly Bird, which makes an appearance in The Enormous Crocodile (1978), The Twits (1980), and Dirty Beasts (1983). Pullman also cheerfully alludes to and quotes from various children’s books, popular adventure tales and even from Spring-Heeled Jack itself (SHJ, p. 85). The latter fact is proudly underlined on Pullman’s website where he claims that ‘[t]his is the first book in the world to feature a quotation from itself (Chapter 11).’ This practice of multiple adapting is – as Hutcheon writes in her preface to A Theory of Adaptation – actually very typical of the Victorian age where adapting happened constantly and ‘in just about every possible direction’ (2006, p. xi). Hence Pullman’s historical children’s novel, set in the Victorian age, is appropriately written in a manner that conforms to the literary practices of the Victorian age.

There are further allusions by means of quotations at the beginning of each chapter: one prominent example is The Three Musketeers (1844) by Alexandre Dumas and the legendary opening of a chapter with the words ‘it was a dark and stormy night’ (SHJ, p. 5). This is – as Pullman most certainly knows – considered to be a piece of utterly bad writing, florid and melodramatic – and was actually first used by Edward Bulwer-Lytton as the opening sentence of his novel, Paul Clifford (1830). It has even sparked off an annual contest in which participants attempt to compose sentences in a similar style.[iii] Clearly, it is up to the lecturer at a university of teacher education or to the teacher in front of his class to decide how far he or she wants to guide students towards an awareness of these intertextual links. The following two examples could well be worth the effort and are rather unlikely to be discovered by students or student teachers themselves: the first one is a link to Charles Dickens and the second one, maybe surprisingly, a link to Miles Kington. Regarding Dickens, the fact that the only possession that the three children carry on them is a valuable golden locket inherited from their mother alludes to Oliver Twist (1838), where the lost gold locket of Oliver’s dead mother plays a significant role in the plot and Victorian London is just as dangerous and hostile a place for children as it is in Spring-Heeled Jack. The link to the writings of the English humourist, Miles Kington, and his particular blend of English and French, known as Franglais, consists of a rather unlikely adaptation that generates one of the funniest moments in the book. The following four lines [End of Page 12] from the menu of the Saveloy Hotel in Spring-Heeled Jack illustrate the debt to Kington’s Franglais:

Le fish avec beaucoup de bones

Le fish avec no bones

Le sauce pour le fish

Le waiter pour le sauce over le fish (SHJ, p. 49)

Originally published as a column in Punch, Kington later published his mostly dialogic pieces of Franglais also collected in book form, such as Let’s Parler Franglais (1984) or The Franglais Lieutenant’s Woman (1987). Inspired by Kington’s Franglais, Pullman clearly enjoyed himself devising a Franglais-Menu for the Saveloy Hotel. And with reference to a Swiss context, where both students and pre-service teachers are either learning or are already familiar with both English and French, this is a particularly rewarding kind of text to read, to analyse, and to enjoy together. The many instances of adaptation and appropriation contribute to the pleasure that different audiences can derive from the book. Julie Sanders rightly asserts that adaptation and appropriation in general ‘are endlessly and wonderfully, about seeing things come back to us in as many forms as possible’ (2006, p. 160). Spring-Heeled Jack certainly provides ample evidence to support her argument.

iBoy

The plot of iBoy is largely determined by its setting in the depressing Crow Lane estate, a collection of high rise blocks of council flats in South-East London, whose inhabitants are surrounded by crime and dire living conditions. The protagonist’s skull is shattered by a stolen iPhone that is thrown from somewhere close to the top of his building. When he awakes in hospital he soon becomes aware of certain physiological changes – bits of the iPhone have remained stuck inside his brain – and by using his new abilities he finds out that Lucy Walker, a girl he is secretly in love with, was raped [End of Page 13] at the same time that he was hit by the iPhone. The remainder of the narrative describes Tom Harvey’s development from an ordinary teenager living with his grandmother into a superhero who uses his powers, despite his doubts, for revenge and attempts to get at the leaders of the Crow gang – one of the criminal gangs that rule life in the buildings. Members of this gang raped Lucy and Tom is particularly keen to get at the man at the top, Howard Ellman, who, as it turns out, may or may not be his father and who is – this is probably a coincidence – called ‘the devil’ (like the superhero in Spring-Heeled Jack).

iBoy is undeniably a novel of the twenty-first century. The narrative frequently refers to other media and their particular modes of expression – to mobile phones, the worldwide web, movies, graphic novels and to traditional novels. Thus, when Tom Harvey comes home from hospital with a scar on his skull, he encounters some members of the Crow gang in front of the entrance to his building: ‘ “Yo, look at that scar, man,” someone said. “Yeah, shit, it’s Harry fucking Potter …” ’ (Brooks, 2010, p. 32; henceforth IB). The allusion to another fictional character with extraordinary skills is linguistically vulgarized and offers to teenage readers a familiar reference from their range of experience. The pleasure in such an allusion or adaptation – according to Hutcheon – is derived ‘from repetition with variation, from the comfort of ritual combined with the piquancy of surprise’ (2006, p. 4). It underlines the pseudo-realism of the narrative, which is also noticeable in the numerous comparisons to other superheroes. The most extended parallels can be found with Spiderman – like the life of the protagonist of this graphic novel, who is changed forever as a result of the bite of a spider, Tom’s life is transformed when some fragments of the iPhone penetrate his skull.

It is emphasized in the narrative that before this decisive intervention, the narrator was an ordinary teenager who felt ‘Kind of OK, but not great’ (IB, p. 1). There is an ironic metafictional comment on the fictitious nature of the novel in the next passage where Tom Harvey declares: ‘I had no major problems, no secrets, no terrors, no vices, no nightmares, no special talents … I had no story to tell. I was just a kid, that’s all’ (IB, p. 2, italics mine). The key sentence in this quotation refers to the fact that there is, so far, no story. The narrator, once he is aware of his powers, which – in addition to his iBrain – include an iSkin (an electric force field that makes him invulnerable) and also the ability to deliver [End of Page 14] paralyzing electric shocks (see Brennan, 2010), tries to come to terms with these changes – and this first happens by means of likening himself to fictional characters, in particular to Spiderman: ‘I couldn’t believe that I was comparing myself to a fictional superhero. It was ridiculous. Absolutely ridiculous’ (IB, p. 79). But while Tom may compare himself to Spiderman, he is in fact very much a personality of his own. Thus the description that C.M. Stephens provides of Peter Parker, Spiderman’s alter ego, can only partly be applied to Tom: ‘Peter Parker is your all-American failure as a teenager, as seen from a youngster’s point of view – unpopular, isolated, and rejected’ (2000, p. 253). Apart from the fact that Tom is not American, he is neither unpopular nor really isolated. However, what Stephens describes as the ‘sense of the gift of superhuman powers being both liberating and empowering and an intolerable, inescapable burden’ (2000, p. 254) is indeed relevant to iBoy as well. Tom repeatedly questions his new status and his special abilities; he is even at the point of renouncing them because he would rather be his pre-accident unassuming self than a superhero who has to keep quiet about his powers and who leads a double life. Unlike Spiderman, Tom does not triumph when he has exacted his revenge and he does not fall ‘prey to vanity and self-aggrandisement’ (Stephens, 2000, p. 252).

As Geraldine Brennan (2010) points out in her review of the book, Tom’s fate and his actions raise serious ethical questions concerning vengeance, justice, evil and remorse. Without this ethical struggle, which is actually central to the novel, it could not – from a pedagogical perspective – be recommended reading for a teenage audience. Tom is faced with an even greater moral dilemma that results from his new extraordinary abilities: ‘There was too much going on out there, too much bad stuff, and I didn’t know how to cope with it all’ (IB, p. 136). The protagonist senses that if he helps an abused child or foils a terrorist plot to kill thousands of people with a biological weapon he may easily overlook serious problems elsewhere. His questioning becomes more and more acute: ‘I couldn’t do everything, could I?’ (IB, p. 137) Knowing that even with his superhero powers he is not God but simply a teenager leads him to contemplating the nature of divine authority:

And besides, I told myself, at least you’re trying to do something about some of the bad stuff, the stuff hat happened to Lucy … and that’s a hell of a lot more [End of Page 15] than God ever does. I mean, God does fuck all, doesn’t he? He just sits there, luxuriating in all his superpowers, demanding to be adored … (IB, p. 137)

Thus Tom Harvey is faced with significant decisions – he is no Superman who can save the whole world; he is overwhelmed by the possibilities of what he could do but worries about what he might overlook, close to him – and ultimately he chooses to act locally rather than globally. This process of decision-making in critical situations is a relevant topic for discussion among student teachers and teenagers because even if they are not equipped with superpowers, they are faced with similar but hopefully much less dramatic choices in their everyday lives as young citizens. Brooks like Pullman before him alludes here to one of his previous novels, Killing God (2009), which is quoted at the beginning of the chapter in which this passage occurs. The quotation is a brief excerpt from a dialogue between the protagonist and a vicar in the course of which she asks the clergyman, ‘God … I mean, what does he actually do?’ (IB, p. 133; Brooks, 2009, 99). When, towards the end of the novel, Tom has saved Lucy and, in the course of this rescue mission, inflicted great pain and injury on various members of the Crow Gang, he contemplates his inner state of mind:

Did I care about them?

Did I feel remorse, any guilt, any shame?

The answer, whether I liked it or not, was no.

And I didn’t like it.

I didn’t like what it made me. (IB, p. 284)

Like discussions about other serious issues such as the death penalty, the moral dilemma that Tom finds himself in belongs to a framework that teenagers can readily apply to their own context and it is bound to provoke lively discussions in the classroom.

Into the Classroom: Further Considerations

Spring-Heeled Jack is an ideal book to be shared in the classroom. Its short chapters, the blend of graphic and conventional novel as well as its engaging and fast-moving plot provide ample moments for teachers to engage their learners in stimulating tasks while the [End of Page 16] curiosity to discover the outcome of the narrative provides a natural impetus for the students to read on. Teachers may choose to point out some of the many allusions in the text, in particular those to which the students might connect as well as those that they single out as suitable learning objectives. Because of the brevity of its chapters, Spring-Heeled Jack also offers itself to be read aloud to a class – in this case the teacher has to make sure that she or he displays the graphic novel sections to the audience.

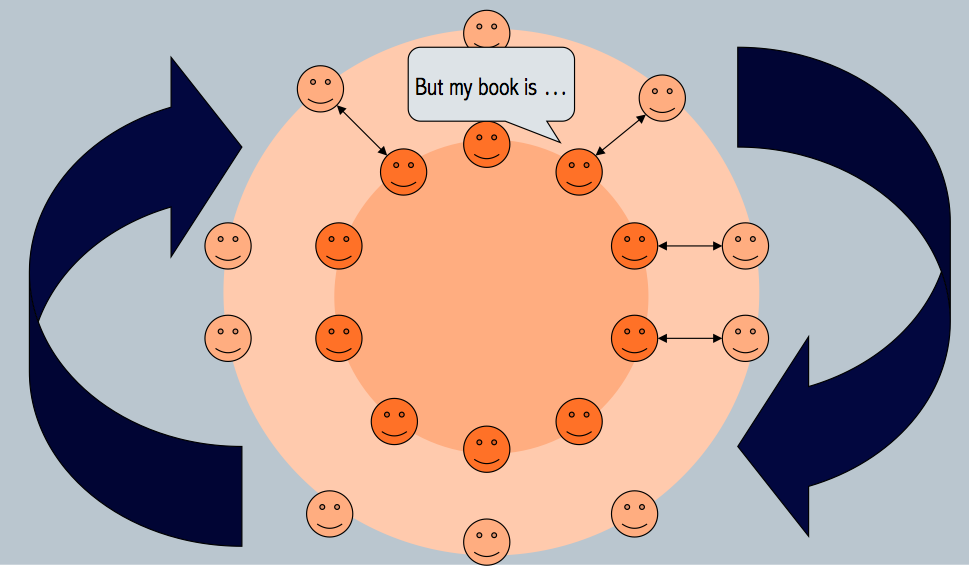

iBoy, in contrast, is a narrative that could feature on a reading list in a classroom that engages its learners in extensive reading. Its controversial contents – rape, violence, and abuse – may require close monitoring of the situation. When read by some students and then promoted in peer exchange activities such as the Marketplace – an adapted version of the 4/3/2 technique by Willy A. Renandya (Bamford & Day, 2008, pp. 95-96) – iBoy will easily find enthusiastic readers.

Figure 1: The Marketplace (based on Renandya, in Bamford and Day, 2008)

Basically, the idea behind the market is to make the students talk about the books that they are reading and thus turn individual experience into a communicative exercise. Students form two circles with their chairs (Figure 1, each smiley represents a learner on a chair). They are told to be prepared to inform their peers about three aspects of the book that they are or have been individually reading, for instance they are asked to inform their first partner for two minutes about the plot of their narrative, the second partner for 1 and a [End of Page 17] half minutes about the protagonist of their text, and the last partner for one minute about their favourite moment in the book. The teacher acts as timekeeper, tells the students when to switch from listening to speaking, and when he calls the time, the students in the outer circle move two chairs forward (clockwise). One advantage of this setting is that the pupils have a natural communicative purpose: they talk to three partners about their book and hence they are motivated to be prepared. The benefits that result from the exercise may be that some learners will hear about narratives that will appeal to them and that they want to read next.

If teachers want to make a greater number of students directly curious about iBoy, a scene such as the moment when Lucy and Tom discuss Spiderman on the roof (IB, p. 215 from the moment when Tom admits to being a wimp until p. 220) may be selected for common classroom reading and discussion. Since most of the students will be familiar with at least some of the movies mentioned on those pages, the question of intertextuality or intermedial storytelling can be addressed and it may well be the scene’s ‘very metafictive nature’ that will enable ‘readers to develop complex interpretive strategies for understanding the ambiguities of word and image’, as Gibson wrote with reference to another book (2010, p. 108).

The media landscape for teenagers and young adults has undergone enormous changes in recent years. As a result, there are critics like Applebaum who predict that in the future, non-linear narrative formats will generate exciting new possibilities (2005, p. 251). Yet, the two novels discussed above succeed primarily as novels. Even though one is a blend of a traditional and a graphic novel and the other is associated by means of numerous textual references to other media, they remain in the first place novels. Undoubtedly new forms will be created and possibly establish themselves (as, for instance, film or computer games have successfully done in the past). However, the short-lived fashion in the sixties of creating loose-paged novels that could be shuffled and read in any order may serve as a reminder that while the form may be reader controlled, the content is not (see Hutcheon, 2006, p. 137). In hypertext as in videogames there is no true choice as all the options have to be written by an author in advance. Ultimately, even today most readers arguably prefer a well-crafted narrative. For teachers who want to encourage [End of Page 18] reading and promote the learning of English, the multiple adaptations in these narratives provide numerous learning opportunities. Adaptation, according to Hutcheon, ‘is how stories evolve and mutate to fit new times and different places’ (Hutcheon, 2006, p.176). By analysing Spring-Heeled Jack and iBoy that in themselves adapt, allude to and merge different media, teachers can demonstrate to their pupils that ‘[i]n the workings of the human imagination, adaptation is the norm, not the exception’ (Hutcheon, 2006, p.177). Moreover, ‘adaptation and appropriation are fundamental to the practice, and, indeed, the enjoyment, of literature’ (Sanders, 2006, p.1).

Bibliography

Brooks, K. (2010). iBoy. London: Penguin.

Brooks, K. (2009). Killing God. London: Penguin.

Dickens, C. (1984). Oliver Twist. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Gay, J. (1986). The Beggar’s Opera. London: Penguin.

Kington, M. (1984). Let’s Parler Franglais. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Kington, M. (1987). The Franglais Lieutenant’s Woman. London: Penguin.

Pullman, P. (1998a). Count Karlstein or The Ride of the Demon Huntsman. London: Corgi Yearling.

Pullman, P. (1991). Spring-Heeled Jack. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Weitz, C. (Director), & Forte, D. (Producer). (2007). The Golden Compass. [Motion picture]. United States: New Line Cinema.

References

Applebaum, N. (2005). Electronic Texts and Adolescent Agency: Computers and the Internet in Contemporary Children’s Fiction. In K. Reynolds (Ed.), Modern Children’s [End of Page 19] Literature. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 250-262.

Bamford, J. & Day, R. (2008). Extensive Reading Activities for Teaching Language. Cambridge, Cambridge UP.

Bobby, S.R. (2012). Beyond His Dark Materials: Innocence and Experience in the Fiction of Philip Pullman. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland.

Brennan, G. (2010). Review of iBoy by Kevin Brooks. The Observer, 11 July. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2010/jul/11/iboy-kevin-brooks-book-review

Campbell, J. (2004). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Carter, J. (1999). Talking Books: Children’s Authors Talk About the Craft, Creativity and Process of Writing. London: Routledge.

Eco, U. (1984). Postscript to The Name of the Rose. Trans. W. Weaver. San Diego: Harcourt.

Ewers, H.-H. (2005). A Meditation on Children’s Literature in the Age of Multimedia. In E. O’Sullivan, K. Reynolds & R. Romǿren (Eds), Children’s Literature Global and Local: Social and Aesthetic Perspectives. Oslo: Novus, pp. 255-268.

Fried, K. (2003). Darkness Visible: An Interview with Philip Pullman. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/gp/feature.html?ie=UTF8&docId=94589

Gibson, M. (2010). Picturebooks, Comics and Graphic Novels. In D. Rudd (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Children’s Literature. London: Routledge, pp. 100-111.

Gorski, E. (2007). Golden Compass Points to Controversy. The Huffington Post, 30 November. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/huff-wires/20071130/golden-compass-religion

Hutcheon, L. (2006). A Theory of Adaptation. New York: Routledge.

Jones, D. & Watkins T. (2000). Introduction. In A Necessary Fantasy? The Heroic Figure in Children’s Popular Culture. New York: Garland, pp. 1-19.

Krashen, S. D. (2004). The Power of Reading. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Lacey, H. (2012). The Inventory: Philip Pullman. The Financial Times, 16 March. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/10f13e1e-6d6f-11e1-b6ff-00144feab49a.html [End of Page 20]

Nünning, A. & Rupp, J. (Eds.). (2011). Medialisierung des Erzählens im englischsprachigen Roman der Gegenwart: Theoretischer Bezugsrahmen, Genres und Modellinterpretationen. Trier: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

Pullman, P. (1998b). Picture Stories and Graphic Novels. In K. Reynolds & N. Tucker (Eds), Children’s Book Publishing in Britain Since 1945. Aldershot: Scolar, pp. 110-132.

Reynolds, K. (1994). Children’s Literature in the 1890s and the 1990s. Plymouth: Northcote House.

Reynolds, K. (2006). His Dark Materials in Performance: Finding a Balance between Heritage and Mass Media. In F. M. Collins & J. Ridgman (Eds.), Turning the Page: Children’s Literature in Performance and the Media. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 185-206.

Reynolds, R. (1997). Superheroes: A Modern Mythology. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Ryan, M.-L. (2011). Transmedial Storytelling and Transfictionality. Presentation at the Giessen Graduate Centre for the Study of Culture, 7 June. Retrieved from http://users.frii.com/mlryan/transmedia.html

Sanders, J. (2006). Adaptation and Appropriation. Abingdon: Routledge.

Stephens, C.M. (2000). Spider-Man: An Enduring Legend. In D. Jones & T. Watkins (Eds.), A Necessary Fantasy? The Heroic Figure in Children’s Popular Culture. New York: Garland, pp. 251-265.

Tucker, N. (2007). Darkness Visible: Inside the World of Philip Pullman. Cambridge: Icon.

Vogler, C. (1998). The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers. Second Edition. Studio City (CA): Michael Wiese Productions.

Waller, A. (2012). Youth Paused: Epiphanies in the Seed-Time of Life. Afterword to PEER. English: Journal of New Critical Thinking 7, 96-105. Retrieved from http://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/english-association/publications/peer-english/7/2012Waller.pdf

Wolf, W. (2011). (Inter)mediality and the Study of Literature. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 13 (3), pp. 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1789 [End of Page 21]

[i] Folktales and fairy tales often feature heroines as well but overall such heroines are largely

passive, submissive and subordinate.

[ii] This moth could easily be perceived as a precursor of the dæmons in His Dark Materials. See also Tucker, 2007, p. 62.