|

From Flat Stanley to Flat Cat: An Intercultural, Interlinguistic Project |

Download PDF |

Abstract

In this article, a Flat Cat Project is shared. Beginning with a description of the initial idea, influenced by the picturebook Flat Stanley (Brown, 1964), an account is given of a paper-plate Flat Cat and its journey across countries and cultures, visiting children who are learning English. The Flat Cat’s visit to Madrid, Spain is described in detail, demonstrating how such projects can support development in areas such as creativity and literacy, and promote intercultural and interlinguistic learning.

Keywords: Picturebooks, CLIL, Creativity, Intercultural Awareness, Shared International Projects.

Teresa Fleta (PhD) is a teacher and teacher trainer. She has carried out research on child language acquisition of English. Currently she teaches in the Master’s Degree Programme on TEFL at Alcalá de Henares University in Madrid.

Elizabeth Forster has been a classroom practitioner for over thirty years. Currently she is a teacher in the British Council Primary School and participates in teaching a module on MA Programme ‘Teaching Young Learners’ at Alcalá de Henares University, Madrid. [End of Page 57]

Introduction

Creativity is said to be at the heart of all teaching, giving teachers and students the opportunity to test ideas in their own ways (Boden, 2001; Pugliese, 2010; Wright, 2006). One way in which teachers can become innovative in class is by getting involved in creative projects as an alternative to traditional teaching methods and the use of course books. With regard to today’s educational contexts, the teaching of content in the different school subjects through another language is becoming commonplace. In many schools, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is burgeoning and has brought about a change in the field of curricular innovation (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010). In this article, we report on the Flat Cat Project, which provided opportunities to work creatively with English, content and culture in classrooms in different parts of the world.

Taking as a springboard creativity and the CLIL approach, the benefits of storytelling, and also the importance of raising intercultural awareness in the classrooms (Kubanek-German, 2000), the first part of this article introduces the pedagogical concepts that serve as a framework for the project. The second part describes the Flat Cat Project and a report on a creative interlinguistic and interdisciplinary activity carried out around Flat Cat and Little Frisbee in a bilingual school in Madrid, Spain. We conclude by reiterating the importance of teaching language, content and culture creatively.

Advantages of Intercultural Creative Teaching

Traditionally, education has focused more on the ability to recall information accurately than on preparing students to become creative. However, creativity is the starting point for any real learning process to take place and the relationship between teaching creatively and teaching for creativity is an integral one (Jeffrey et al., 2004, p. 84).

Teachers become creative in class when they engage students actively in the learning process and when they make the teaching and the learning more interesting (Pugliese, 2010). One argument in favour of teachers creating their own teaching materials and resources is that textbooks often do not meet the needs of the students because they either restrict the topics to a specific culture or because they only reflect the beliefs and opinions [End of Page 58] of the authors or the curriculum designers who wrote them. As stated by Boden (2001), ‘creativity is not the same thing as knowledge, but is firmly grounded in it. What educators must try to do is to nurture the knowledge without killing the creativity’ (p. 102). Another argument for adapting teaching materials is to respond to the demands of today’s classrooms. Schools should review the role of creativity and cultural education in their curricula because ‘developing creativity involves, amongst other things, deepening young people’s cultural knowledge and understanding’ (NACCCE, 1999, p. 11).

One way in which teachers can involve children in the learning process is by promoting creativity across the curriculum. As Wright (2006, p. 17) points out: ‘… making new connections is what creativity is! Wandering and wondering without clear goals is more important than linear thinking if you want to make new connections and to discover new things’. Creativity is a multi-faceted concept and many different methodologies and teaching approaches can aid its development. One approach is especially relevant to the content of this article and that is CLIL. In recent years, many schools have implemented a CLIL approach. The benefits of this approach have been shown to help learners both cognitively and affectively (Coyle et al., 2010), while it enables teachers to present language and content in an innovative and non-traditional way. The L2 plays an essential role in learning as it is the vehicle through which the subjects (maths, geography, art, culture, etc.) are taught, thus benefiting both content and language subjects. In the project described in this article, the language specific to all learning areas was introduced to children in a natural way with a view to developing participation in the L2.

Stories for Holistic Learning

Within the framework of CLIL, another excellent resource to teach children holistically is through the use of stories (Dunn, 2013; Ellis & Brewster; 2002). Oral stories and picturebooks appeal to young learners’ interests and contain all the ingredients for language and content learning, because ‘stories are the cornflakes of the classroom. Cornflakes contain a wide range of nutritional elements. A plate of cornflakes a day provides a good basic set of the elements we need. Stories are similar’ (Wright, 2000, p. 3). [End of Page 59] According to Cameron, when foreign language learners share picturebooks in class, they get the meaning of the words from the book illustrations and through the context:

Children listening to a story told in a foreign language from a book with pictures will understand and construct the gist, or outline meaning, of the story in their minds. Although the story may be told in the foreign language, the mental processing does not need to use the foreign language, and may be carried out in the first language or in some language-independent way, using what psychologists call ‘mentalese’. (Cameron, 2001, p. 40)

Thus, stories and picturebooks are considered an essential part of the teaching and learning because they allow learners to learn language and to infer meaning. When children are read stories in class, they have access to vocabulary, intonation, grammatical structures and formulaic language within a context and at the same time, they develop an understanding of the plot. When teachers read stories to children, they are offering them opportunities for holistic learning.

CLIL and Culture

One of the basic components of CLIL is the cultural aspect of what goes on in the classroom. Byram et al. state:

The ‘best’ teacher is neither the native nor the non-native speaker, but the person who can help learners see relationships between their own and other cultures, can help them acquire interest in and curiosity about ‘otherness’, and an awareness of themselves and their own cultures seen from other people’s perspectives. (Byram et al., 2002, p. 10)

In today’s classrooms, the role of foreign language teachers can be seen as a mediator not only between language and content and between theory and practice, but also as one that builds multicultural awareness.

In addition, among the multiple positive effects of using stories and picturebooks to teach children, they can support the introduction of a cultural component into the [End of Page 60] curriculum, and as stressed by Cameron (2001, p. 168): ‘stories can help children feel positive about other countries and cultures, and can broaden their knowledge of the world’.

The Flat Cat Project described in the next section includes all the elements previously mentioned and places a real emphasis on the intercultural dimension. These are vital ingredients that prepare children in today’s classrooms to understand, respect and learn from other cultures.

From Flat Stanley to Flat Cat

An international workshop session gave rise to the ideas that fueled this shared pedagogical experience. The projects presented here began with the Flat Stanley picturebook (Brown, 1964). Flat Stanley was the first of a series of Flat Stanley stories. The main character, Stanley wakes up one morning to discover that a bulletin board above his bed has fallen on him and flattened him. He is taken to the doctor and though apparently fine, he is only half an inch thick. Being flat allows Stanley to have adventures and do fun things, like going under closed doors, squeezing between bars, flying like a kite, travelling on holidays to California through the post in an envelope or, hidden in a picture frame, helping the police arrest some art thieves, for which he is awarded a medal. This picturebook prompted the Flat Stanley Project, created by a schoolteacher in Canada (Hubert, 1994), where children were encouraged to send pictures/cut-outs of Flat Stanley to schools or to family members in other parts of the country, or around the world, to have adventures. The picture/cut-out was then sent back with information about the places Flat Stanley had visited.[i]

Using the idea of the Flat Stanley Project, the Flat Cat Project emerged from a workshop called ‘Creating Language Rich Arts & Crafts Projects’,[ii] in which the groups of participants (teachers and educators) made cats, later called ‘Flat Cats’, from paper plates and craft material. The idea was that each Flat Cat was to be taken into classrooms around the world with a view to sharing and discussing a particular topic related to teaching English to children. The cat would then travel from country to country accompanied by a [End of Page 61] pack of pedagogical materials, which had been created by the children and their teachers in each classroom visited.

The Project – the Journey Begins

The project unfolded in a versatile way in different countries, different cultural contexts and with different age groups. The teaching strategies used by the teachers were tailored to the children’s ages and their specific needs and appealed to the children’s interests

Cool Cat (Figure 1), one of the Flat Cats that left Brighton after the workshop, was a fun-loving party cat; her objective was to discover the different ways children celebrated birthdays in the countries she visited. At the time of writing this article, Cool Cat had visited Portugal, Estonia, Spain, Slovakia, Switzerland and Latvia, the United Arab Emirates and Cameroon. However, this article focuses primarily on the experiences of a group of children with Cool Cat in Madrid, Spain.

Cool Cat in Madrid

Before arriving at a school in Madrid, Cool Cat had visited children in Portugal and Estonia. Table 1 gives a short summary of the activities in these countries and what the pedagogical pack contained when it arrived in the Madrid classroom (see also Fleta & Mourão, 2012).

Cool Cat arrived in the classroom of a group of Year 2 children (aged 6 to 7 years old), receiving bilingual education in Spanish and English in Madrid. Before Cool Cat’s arrival, the children’s teacher read them the original Flat Stanley picturebook. To set up this Flat Cat’s arrival, the children were told that when Flat Stanley was flattened, his pet cat was with him and so the cat was flattened too and became a Flat Cat; a perfect introduction to the project. The teacher told the children that one of Flat Cat’s wishes was [End of Page 62] to celebrate his birthday in Spain, and to visit the famous Spanish museums to see other Flat Cats in paintings by Spanish artists.[iii] (In one of the picturebook episodes, Flat Stanley helps the police arrest some art thieves.)

Table 1: Cool Cat’s experiences prior to Madrid, Spain

| Country | Age | Activities | Pedagogical pack |

| Portugal | 5-6 years old |

|

|

| Estonia | 9-10 years old |

|

|

Art activities

The children were introduced to Flat Cat’s past experiences, and together they traced his route from the UK to Portugal, Estonia and then Spain. They wrote and illustrated welcome cards with the Spanish flag and the Madrid shield. Flat Cat was then granted his birthday wish, namely to visit museums and to look for cats in Spanish paintings. This resulted in a number of paintings containing cats shown to the children, including: [End of Page 63]

- Retrato de Don Manuel (Goya [1746-1828], 1787-88)

- Gato Acosado (Goya, 1788)

- Riña de Gatos (Goya, 1786)

- Las Hilanderas (Velázquez [1599-1660], c. 1657)

- Clotilde con Gato (Sorolla Bastida [1863-1923], 1910)

- Dora Maar con Gato (Picasso [1881-1973], 1941)

- El Pequeño Gato (Miró [1893-1983], 1951)

- Invention of Monsters (Dalí [1904-1989], 1937)

Flat Cat especially liked Miró’s El Pequeño Gato (The Small Cat, see Figure 2). In fact, he liked it so much that when he was at the museum, he jumped into the picture and became Miró’s ‘Small Cat’! Several art lessons were devised for the children based on Miró’s style and technique, with a focus on lines, shapes and primary colours.

Figure 2: A child’s drawing of Miró’s ‘Small Cat’ [i]

The children were told that Miró liked to paint with primary colours and to draw lines and shapes (Mason et al, 1995; Mink, 1999). On the interactive whiteboard, they were shown how to draw a picture imitating Miro’s techniques based on ‘crazy characters’.[i] They were given sheets of paper and were asked to draw, in pencil, a figure as big as the page. The figure had to have a head and could be running, sitting, flying or dancing. The children could also draw shapes. They then coloured their pictures using pencil crayons, big wax crayons and marker pens (see Figure 3). [End of Page 64]

Figure 3: Drawings by children

Once completed, the pictures were displayed in the corridor for the school community to see; the children were encouraged to explain what they had done and how they had done it to anyone who asked. This art activity gave the children an opportunity to bring into play a wide array of abilities. Not only were they placed in the role of artist, they were also called upon to explain their creative process. This evidenced a broad spectrum of metacognitive skills and produced real linguistic challenges. Each individual responded to these challenges at a different level, but all were observed feeling a real measure of achievement and a sense of ownership of the finished product.

Literacy activities

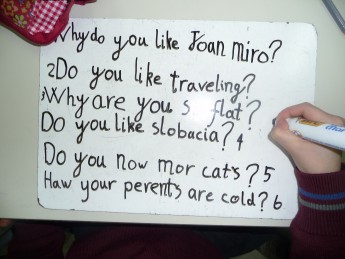

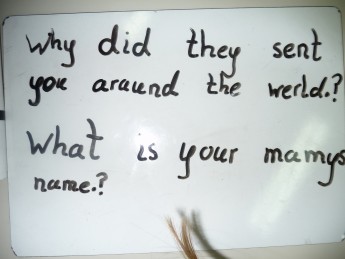

The children had been read the story of Flat Stanley and had heard of Flat Cat’s experiences in Portugal and Estonia, so they were naturally curious as to how he felt about his adventures. As a result, each child was asked to prepare two or three questions to ask Flat Cat on the class interactive whiteboard (see Figure 4). Their questions were about: Brighton, Portugal, Estonia and Slovakia; Christmas in Spain; Spanish artists; Miró; likes and dislikes, etc. The children then played the ‘Hot Seating’ game and different pupils volunteered to take on the role of Flat Cat and answer the questions. This activity gave the [End of Page 66] children an opportunity to use the grammar skills learned in an earlier classroom situation in a more relevant, fun way.

Figure 4: Some questions for Flat Cat on children’s mini-whiteboards.

With children of this age, one of the language learning aims is to promote literacy; thus, their teacher encouraged the children to write in English as much as possible. Another writing activity involved writing poetry. Children were asked to write a poem for Flat Cat with words rhyming with ‘cat’ or with ‘flat’. These poems were illustrated and read out to the class. An example follows:

I love the flat cat

She sits on a mat

Wearing a nice hat

She’s eating a rat.

I love you flat cat.

The children then sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to Flat Cat in English and Spanish and recorded some of their poems. The materials forwarded to Slovakia, the next destination for Flat Cat, included not only all the content from Portugal and Estonia, but also a Flat Cat pendant (Flat Cat’s present), welcome cards with the Spanish flag and Madrid shield, Flat Cat poems, Miró paintings, a CD with ‘Happy Birthday’ songs and recordings of the children’s poems. [End of Page 66]

An Interlinguistic, Interdisciplinary Project

Little Frisbee

Like ripples on a pond, this idea was taken up by the head of primary Spanish,[i] who had been invited to observe one of the Flat Cat lessons. Inspired by the Flat Cat Project, she invented Frisbee the Dog (Figure 5), and wrote a story about a little dog who was so tiny that he could travel around the world in a small box, visiting countries where Spanish is learnt as a second language. Like Flat Cat, Frisbee came to Madrid and was introduced to Spanish culture and the most famous monuments of Madrid.

Figure 5: Frisbee

In any bilingual school environment, the two language curricula usually run parallel to each other, with very few connections between them. Frisbee created a link, as the Spanish Department was able to use the visiting dog with several different Year Groups, involving them in activities such as talking about the weather and seasons in Madrid, or taking Frisbee along on a school excursion to visit the Royal Palace (see Figure 6) and later including Frisbee in the follow-up activities; or by placing Frisbee in many different kinds of houses and homes which had been prepared during the English lessons (see Figure 7). All these activities served to strengthen the connections between the Spanish and English curricula and gave the different language teachers real opportunities to plan together and make more efficient use of the materials prepared by the children.

Figure 6: A poster in Spanish showing Frisbee on a school trip around Madrid [End of Page 67]

Figure 7: Frisbee in different kinds of houses

Thus, Flat Cat and his Spanish counterpart, Frisbee, allowed teachers to interlink the content of both the Spanish and English curriculum.

Discussion

Internationally shared projects like the Flat Cat and Frisbee Projects seek to meet the needs of today’s multilingual and multicultural classrooms by building bridges across languages, cultures, and countries. The fact that they integrate language, content, communication, cognition and culture makes them easily adaptable to a school curriculum. Besides this, they involve different teaching modes (communicative, linguistic, artistic, digital, and social), which foster the children’s imagination and creativity.

Based on the responses from the different host countries and the material both received and sent, this international and interlinguistic pedagogical experience is a concrete example of intercultural communication, involving the sharing of ideas and activities that can be adapted by other teachers in their different national contexts. It is a project that promotes young learners’ creative abilities, and shares materials and ideas creatively. It certainly provided memorable moments that deepened cultural knowledge [End of Page 68] and understanding. International projects with these characteristics are suitable for introducing English or any other language to learners of different ages and at different language levels.

In today’s diverse society, exposure to multilingual and multicultural learning settings is highly beneficial for language and content development, and also for raising intercultural awareness. The Cool Cat / Flat Cat experience has built bridges between the cultures of the different countries; teachers and children have engaged in intercultural interaction and investigated different resources and activities that could be developed to present the culture of their own country. The multimodal resources created by the young learners in most countries contributed to the developing of different intelligences: visual (posters, art work, photographs, videos, CDs), auditory (songs, poems and rhymes) and kinesthetic (games, dances and crafts). Some have also incorporated various technologies (white boards, recording instruments).

Flat Cat’s trip to Madrid differed somewhat from his visits to the previous countries, since the students were brought back to the original Flat Stanley story, and the picturebook played a very important role. Flat Cat’s visit to Madrid contributed to the development of interlinguistic and interdisciplinary work in this particular classroom in a bilingual school. Nevertheless, although the project aims changed slightly in each setting, the students’ experiences were rewarding in all countries. [End of Page 69]

Bibliography

Brown J. & Nash, S. (2006). Flat Stanley. London: Egmont Press.

References

Boden, M. A. (2001). Creativity and knowledge. In A. Craft, B. Jeffrey and M. Leibling (Eds.), Creativity in education. London: Continuum, pp. 95-102.

Byram, M., Gribkova, B. & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the Intercultural Dimension in Language Teaching: A Practical Introduction for Teachers. Strasbourg: Language Policy Division, Directorate of School, Out-of-School and Higher Education, DGIV, Council of Europe.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coyle, D., Hood, P. Y. & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dunn, O. (2013). Introducing English to Young Children: Spoken Language. Glasgow: Harper Collins.

Ellis, G. & Brewster, J. (2002). Tell it Again! The New Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Fleta, T. & Mourão, S. (2012). Using picturebooks to connect learning across the curriculum : the Flat ‘Cool’ Cat experience. In In A. Torres, L. Villacanas de Castro, B. Soler Pardo, (Eds.). Proceedings of the 1st International Conference: Teaching Literature in English for Young Learners, Facultat de Magisteri Universitat de València, 25-26 October 2012. Valencia: Reproexpres Ediciones. Available at:

Jeffrey, B. & Craft, A. (2004). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity: distinctions and relationships. Educational Studies, 30(1), 77–87.

Kubanek-German, A. (2000). Emerging intercultural awareness in a young learner context: a checklist for research. In J. Moon & M. Nikolov (Eds.), Research into Teaching English to Young Learners: International Perspectives, Pécs: University Press Pécs, pp. 49-63.

Mason, A. Andrew; S. Hughes & Barron, J. (1995). Miró (Famous Artists). New York: Barron’s Educational Series.

Mink, J. (1999). Joan Miró. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag.

NACCCE (1999). All our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education (London: DfEE). Available at: http://sirkenrobinson.com/pdf/allourfutures.pdf

Pugliese, Ch. (2010). Being Creative: The Challenge of Change in the Classroom. Surrey: Delta Publishing.

Wright, A. (2000). Stories and their importance in language teaching. Humanising Language Teaching, 2(5). Accessible at: http://www.hltmag.co.uk/sep00/martsep002.rtf

Wright, A. (2006). Being creative: things I find useful. Children And Teenagers: C&TS. The Publication of the Young Learners and Teenagers Special Interest Group, IATEFL. 06(1), 18-19.

[i] Information about this project can be found at: http://www.flatstanley.com/

[ii] Part of the International Association of Teachers of English as Foreign Language (IATEFL) Pre-Conference Event organized by the Young Learner and Teenager Special Interest Group (YLTSIG) held in Brighton in 2011.

[iii] Readers will notice that in Spain, Cool Cat became masculine, and her name changed from Cool Cat to Flat Cat!