|

From Reading Pictures to Understanding a Story in the Foreign Language |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This paper discusses the impact of pictures on children’s understanding of a story during their first encounter with the picturebook The Smartest Giant in Town. The study was conducted with a group of 24 children aged between 8 and 9 years in a German primary school. The recorded classroom discourse revealed that children scanned the pictures for clues and actively constructed meaning from them. Learners demonstrated a solid understanding of the relevant situation, which enabled them to make accurate predictions about the developing narrative on the basis of the illustrations within the picturebook. Data from interviews with three groups of four to five young learners each showed that the children were able to jointly reconstruct the storyline 12 months after their first and only encounter with the picturebook. These findings suggest that one encounter with this picturebook helped to create a meaningful context, within which vocabulary knowledge can be expanded during repeated encounters with the story.

Keywords: EFL, vocabulary learning, picturebook, visual images, The Smartest Giant in Town, intertextuality.

Annett Kaminski is a qualified secondary school teacher with experience at secondary and tertiary level in Germany and the UK. She currently teaches language, cultural studies and children’s literature to future primary school teachers at the University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany. Her main research interest is the use of stories, poems and songs in the primary English classroom with a special focus on vocabulary learning. [End of Page 19]

Introduction

The picturebook project reported on here is part of a longitudinal study that was carried out from 2007 to 2010 to investigate the use of stories, songs and poems and their impact on vocabulary learning in primary English as a foreign language (EFL) classrooms in a medium-sized town in the southwest of Germany. This longitudinal study followed a multi-method design applying quantitative research instruments such as a questionnaire distributed to 135 primary school teachers in 21 local schools as well as qualitative research instruments such as extensive participant observation with two teachers in one school and in-depth interviews with these teachers as well as their young learners. The choice of research methods, data collection and analysis procedures has been influenced by an ecological worldview as suggested by Lier (2004), by an ethnographic approach to classroom research (Davis, 1995; Watson-Gegeo, 1988), case study approaches (Cresswell, 2007) and discourse analysis (Cameron, 2001).

One early finding of the questionnaire in 2007 was that illustrated stories and picturebooks in English were popular with primary school teachers. Though not used as often as songs and rhymes, 70% of the teachers reported using illustrated stories at least a few times every school year. During the three observational periods in 2008 and 2009, I was able to observe more than ten illustrated stories and picturebooks being used in primary EFL classrooms. However, there was a tendency to use texts specifically created and illustrated for teaching purposes more often than authentic picturebooks. All in all, there were only three picturebooks that entered the classrooms in all of the 41 lessons that I observed during 2008 and 2009, and only two, namely Froggy Gets Dressed (London & Remkiewicz, 1994) and The Smartest Giant in Town (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2002) were read from cover to cover without simplifying the plot or language for pedagogic reasons, thereby giving the children a chance to experience the authentic language of the picturebook.

In many storytelling sessions, however, whether it be illustrated stories or picturebooks, I was able to observe something that can only be described as the magic of storytelling: children totally absorbed in the story and the pictures, indulging in the experience of being told a story, enchanted by what they saw and heard, even trying to join [End of Page 20] in by copying some of the teacher’s language. By doing so they demonstrated an understanding of the context and they appeared to be following the storyline. But how were these learners making sense of the story being told in English? Were the pictures supporting their sense making?

If we assume that teachers use illustrated stories and picturebooks in the EFL classroom not just for entertainment reasons or to boost motivation levels but also for language learning (Elley, 1989), then a good understanding of what happens during the first encounter with such a text is crucial for a positive learning outcome. In this paper, I would like to analyse a storytelling session with The Smartest Giant in Town (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2002) and explore the following questions:

- How do the children respond to the picturebook being told in English?

- How do pictures assist learners in understanding the story?

- What is the longer-term impact of this first encounter with the picturebook?

- What are the implications for teaching?

Theoretical Background

The use of picturebooks in the teaching of native children of English has become well integrated with time set aside for storytelling and reading in kindergartens and primary schools in English-speaking countries. Studies in first language (L1) acquisition, such as Elley (1989) have demonstrated that illustrated literature can support word growth of up to 40% if vocabulary is explained through the use of synonyms or by pointing at an illustration. As the most influential factors attributing to the children’s word learning, Elley identified ‘the frequency of occurrence of the word in the story, the helpfulness of the context, and the frequency of occurrence of the word in pictorial representation’ (1989, p. 184). Pictures are seen as an important ingredient for the meaning-making process, which has also been supported by researchers who studied children’s response to visual representations in picturebooks (Arizpe and Styles, 2003; Doonan, 1993).

A positive impact of reading illustrated literature has also been found in classroom settings where children learn English as their second language (L2). The Book Flood project (Elley and Mangubhai, 1983) carried out in rural primary schools in Fiji [End of Page 21] showed that extensive and repeated exposure to high-interest illustrated literature impacted positively not only on the progress children made in their L2 but also in other subject areas. With regard to L2 learning, the authors concluded that children ‘can learn new structures from relatively uncontrolled materials, provided there is the support of cues from pictures, absorbing context, and teacher guidance’ (Elley and Mangubhai, 1983, p. 66).

It is the first encounter with the book, the moment that the child looks at the pictures and hears the story unfold in the foreign language for the very first time that learning is set into motion. If we want to know more about the beginning stages of this process and its impact on future learning, we need to take a microscopic view of the actual storytelling session and the children’s verbal response.

Method

Participants

One Year 3 group of 24 children aged between 8 and 9 years took part in the storytelling session which is the focus of this paper. 50% of these children were bilingual, speaking German at school and a different language at home. The most common home languages were Russian, Polish, Italian, and Roma, but there were also children whose mother tongue was Portuguese, Spanish or Hungarian. All of the 24 children had been provided with regular English tuition of approximately 50 minutes per week as one session or divided into two sessions of 25 to 30 minutes since they had started school in Year 1.

Procedures

Observations

The above mentioned storytelling session took place in the second observational period in 2009. Both observational periods stretched over several weeks and involved seven teachers and eleven classes in total. However, in each of the two observational periods, there was special focus on one of the teachers and their classrooms, with extensive weekly, at times even daily contact with each of the two teachers and their learners: [End of Page 22]

|

Observational periods in |

Nº schools |

Nº |

Nº |

Nº recordings |

Nº teachers |

Nº classes |

|

2008 |

2 |

6 |

15 |

13 |

4 |

6 |

|

2009 |

1 |

14 |

26 |

7 |

3 |

5 |

Table 1: Observation Matrix for 2008 (February to April) and 2009 (February to June)

I took on the role of participant observer, and joined in with all the activities. Participant observation seemed an effective way to proceed, not only to explore the workings of the primary English classrooms but also to address the teachers’ wish for a mutual working relationship and to adhere to ethical principles of research in Applied Linguistics (BAAL, 2006). Field notes were written down immediately after observations had taken place and wherever possible and appropriate, classroom discourse was audio-recorded.

In line with ethnographic research tradition, it was regarded as good practice for the researcher to be ‘immersed in the day-to-day lives of the people’ (Cresswell, 2007, p. 68) and therefore to get involved in the teaching process itself, and to act as an assistant to teachers supporting them in every way possible, whether that included sharing teaching ideas and material or working with children during busy periods of group work or self-directed periods of learning, thus gaining an insider perspective. The storytelling session that is reported on here is an example of this close working relationship. I tried to replicate a storytelling session I had observed, as one of the teachers I was working with invited me to read The Smartest Giant in Town to another Year 3 group using the same technique she had used a few days previously. The method that the teacher had used placed great importance on the visual aspect of the picturebook. The children sat close to the teacher in two semicircles so that they could always look at the picturebook as she held it up. On turning the page, the teacher let the children look at the pictures and waited for their ideas and comments, which usually came in German. The teacher would respond to the children’s comments by nodding or reformulating parts of their contribution in English thereby introducing English words that would appear in the text of that particular double-page spread in the book. This method of presenting children with material and inviting [End of Page 23] their comments is not unusual in a primary school setting in Germany and is a commonly used technique in other subjects.

Interviews with children

The interviews with 13 children were conducted during their regular English lessons in March 2010. The interviews took place outside the children’s classroom in the self-study area in the main hallway. All interviews were audio-recorded. The three interviews with the children, all of whom had taken part in the shared reading of The Smartest Giant in Town, were between 28:25 and 35:55 minutes long. Following Moon’s (2000) advice to avoid individual interviews with children so as not to intimidate them, there were four to five children in each group. Only children who wanted to be interviewed were chosen.

The interviews followed a semi-structured design consisting of a warm-up phase in which the children were asked to open their portfolios and talk about activities they had enjoyed and others that they had not. Children were encouraged to extend their answers and explain reasons for their approval or disapproval of certain activities. This first phase of the interview was carried out in German. In a second phase, children were presented with a set of 65 coloured cards each showing a different picture. These pictures depicted object names (such as pieces of furniture, fruits, animals) that they had learnt as well as numbers, scenes from family life and from stories they had heard and talked about, among them were five cards featuring characters of The Smartest Giant in Town.

Children were told that they would play a game whereby they could collect cards: whenever it was their turn to choose one of the nine cards displayed from the top of the pile, they could say something about their card in English. Once they had talked about the picture on the card, which could be anything from a single word to a sentence, they would keep the card and later get a copy of all of their cards for their portfolio. All instructions were given in German, but if children wanted to know a word in English, it was provided to them and repeated a few times. The main aim was to establish a friendly atmosphere where children did not feel intimidated. The interview was not seen as a tool to test children’s knowledge but rather to give them some stimuli to speak English and to provide a platform for them to raise any concerns or issues they had about the subject. [End of Page 24]

Material

Figure 1: Front cover

The Smartest Giant in Town by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler, Macmillan Children’s Books, London, UK.

The Smartest Giant in Town written by Julia Donaldson and illustrated by Axel Scheffler was first published in 2002. A German version did not enter the German book market until May 2009 when a translation by Susanne Koppe became available. Teaching material for German speaking teachers of English on The Smartest Giant in Town appeared in June 2009 (Rebenstorff, 2009). It is thus safe to say that none of the children had seen or read a German version of the picturebook before the storytelling session took place in March 2009. Nevertheless, many children must have had experience of reading books by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler. Many of their books have been translated into German and are used in German kindergartens and schools. So, although the children cannot have known the German version of The Smartest Giant in Town prior to the storytelling session, we have to acknowledge that they could be experts in understanding the characteristic styles of narration in text and illustration. It is a story told in rhyme, containing rich, complex language that includes some infrequent vocabulary. It shows characters that seem weak but demonstrate great strength as well as a good sense of humour, and elaborate [End of Page 25] illustrations that extend the plot in particular through the many references to well-known traditional stories.

In The Smartest Giant in Town, George, the main character, is introduced as a giant whose scruffiness impairs his self-confidence and leaves him with the desire to change his appearance. On noticing a new shop, he decides to buy a new tie, new trousers, new shoes, new socks and a new shirt. Walking home in his new clothes he meets various animals all in dire need of some help. For example the giraffe that George meets first is cold and would like a warm scarf. So, George hands over his tie without hesitation and leaves behind a grateful giraffe. On his walk home he gives away articles of his clothing to help a goat who lost its sail, a mouse whose house burnt down, a fox whose sleeping bag fell in a puddle and a dog who needed to get across a bog. George thus turns from smartest giant into kindest giant and is crowned as such on his return home wearing his old clothes again. All the animals that helped him are there to say thank you with a card and a crown.

The narrative exhibits some of the prototypical features found in traditional folk tales. Just as the main character in a fairy tale has to solve several riddles or fight against a certain number of beasts each bigger and stronger than the one before, George faces a number of situations in which he has to help another creature, and the sacrifices he makes become bigger each time. It is one thing to give away one’s tie, it is entirely another to give away a shoe and a sock and continue one’s journey barefoot. The repetitive verbal text contains recurrent phrases in the dialogue between George and the animals such as ‘What‘s the matter?’, ‘Cheer up’ and ‘I wish I had…’. Moreover, there is the repetition of the cumulative song that George sings each time he has helped an animal. The song represents a summary of the plot, and highlights the irony of George’s situation:

My tie is a scarf for a cold giraffe,

My shirt’s on a boat as a sail for a goat,

My shoe is a house for a little white mouse,

One of my socks is a bed for a fox,

My belt helped a dog who was crossing a bog,

But look me up and down,

I’m the smartest giant in town.

(Donaldson & Scheffler, 2002, unpaginated) [End of Page 26]

Dialogue and song may both act as ‘a way into the story’ (Cameron, 2001, p. 163), both for understanding the story as well as for productive language use. Singing the song or quoting the verbal exchange between George and the animals can be seen as a first step towards retelling the whole story.

The illustrations accompany the verbal text and it is possible for children to understand what is happening through the illustrations only. However there are also many visual references to characters from traditional tales and nursery rhymes: we can see Puss-in-boots; the mouse family living in a shoe is a reminder of the nursery rhyme There Was an Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe; pigs from The Three Little Pigs are found on different spreads; the three bears from Goldilocks and the Three Bears are walking in the countryside; the black sheep from Baa, Baa, Black Sheep is carrying bags of wool; a princess walks sadly alongside her frog prince and dwarfs and giants appear in the town scenes. These are just a few of the references which children might notice if given time to look and make connections.

Data Analysis

In the following, I will focus on three extracts from the audio-recorded classroom discourse of the 21:01-minute long storytelling session in March 2009 and one extract from the audio-recorded 28:25-minute long interview conducted in March 2010.

All discourse data are presented in a table with two columns for two participant groups, the researcher as teacher (TR) and learners (Cn for children, Cm/Cf for male or female child). By adapting a layout that has been suggested by Ochs in her paper Transcription as Theory (1979), it is hoped that top to bottom bias is reduced to a minimum in order to address potential differences in adult and child communication patterns and cognitive behaviour. In addition, the separation of teacher and learner talk produces a visually accurate representation of the amount of teacher talk in relation to learners’ contributions. Since the teacher sets stimuli for learners, and therefore initiates discourse, it is regarded appropriate to present the teacher’s talk in the left column.

Transcription conventions have been adapted from Dalton Puffer’s study on classroom discourse (2007) and are laid out in the appendix of this paper. [End of Page 27]

Classroom discourse

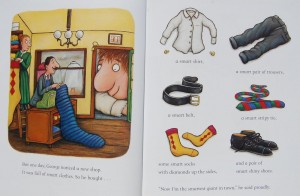

Children first responded to the picturebook when the first double page had been read, and the page was turned to reveal the second double spread showing George peeking into a shop where two shop assistants were handling enormous socks and where on the right hand side different parts of clothing could be seen such as a shirt, a pair of trousers, a belt, a tie, a pair of socks and a pair of shoes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Double-page spread 2 (second opening)

Figure 2: Double-page spread 2 (second opening)

The Smartest Giant in Town by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler, Macmillan Children’s Books, London, UK.

The turning of the page is accompanied by a silence that is 6 seconds long. The reason why there is no immediate response from the children may well be that they are busy scanning the pictures, processing the information that is provided through the pictures before some of them show signs of astonishment (2). Only then, there is a first remark referring to the situation displayed in the pictures (4). This response is unusual since it is in English. The girl who makes it speaks American English and Spanish at home, and German at school. As we will see, a striking feature of all of this classroom discourse is that the children tend to respond in their mother tongue or German, which is either their mother tongue or their L2, but the language most commonly used at school.

After this first statement by a child, the teacher then extends the response by adding a question: ‘Where is it?’ (5). The boy who speaks next refers to a ‘shoe shop’ (6). [End of Page 28] Although he uses German, he answers the teacher’s question posed in English (5), thus signalling that he understands the contributions in English made before. As the discourse unfolds, children sometimes seem to relate their answers to the teacher’s remarks as in turns 8 and 12. However, at other times the children’s responses may not necessarily relate to somebody else’s contribution. Examples are turns 10 and 14. These remarks could also be regarded as individual responses linked to what that particular child discovers in the pictures and the conclusions they draw from them. A new thought is introduced in turn 10; whereas in turns 14 and 16 children repeat or extend what has been said before: ‘shop’, ‘shop for clothes’. It is difficult to judge if this indicates that the children do not really listen to one another, or if it is simply their way of extending someone else’s answer. We cannot assume that children follow the same communication patterns as we anticipate in adults, and moreover, they are distracted, since they are looking at the pictures trying to work out their meaning and they may thus not be able to process everything that is being said.

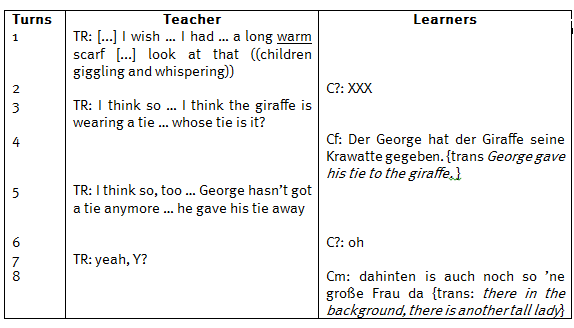

Extract 1, Storytelling Session The Smartest Giant in Town, double-page spread 2, March 2009 [End of Page 29]

However different their first thoughts on the pictures might be, each new comment provides a possible thread for uncovering the ideas conveyed in the illustrations, and so they jointly construct meaning here on the basis of the pictures before they have listened to this part of the story.

A similar pattern can be detected at the turn from third to fourth double-page spread, shown in Extract 2. On the left page, children can see the two shop assistants busy with George’s old clothes, while on the right the whole page is covered with an illustration of a sad giraffe and a concerned looking George touching his tie with one hand.

Extract 2, Storytelling Session The Smartest Giant in Town, double-page spread 3 – 4, March 2009

The children’s giggling and whispering accompany the turn of the page: they have probably made out the giraffe wearing George’s scarf. Almost immediately a child talks about this observation but the background noise makes it unintelligible. Still, judging from the teacher’s comment, we can deduce that this child mentioned the scarf but no more (the teacher’s question suggests that the child did not yet say whose scarf it is, so the child can’t have related it to George’s scarf). Another child steps in quickly and explains displaying a clear understanding of the situation. At the same time, the children seem busy scanning the picture for information as comments in turns 6 and 8 suggest. Once more, there is [End of Page 30] astonishment (6). One boy has noticed another lady giant and talks about his discovery. There are other visual details here that are not mentioned by the children at that moment: Hansel and Gretel, one of the three pigs, Hans in Luck, a dwarf, and a hare to name but a few. We have to assume that not all of these intertextual references are found immediately with the children concentrating on reaching a basic understanding of the storyline during this first encounter with the story. Yet, the boy’s comment on the other lady giant points out that there are many different layers in this picturebook that can be explored. There is a richness of visual stimuli. Multiple readings of the picturebook are needed to discover all these visual clues, and in turn these visual clues could provide an invaluable source for discussion.

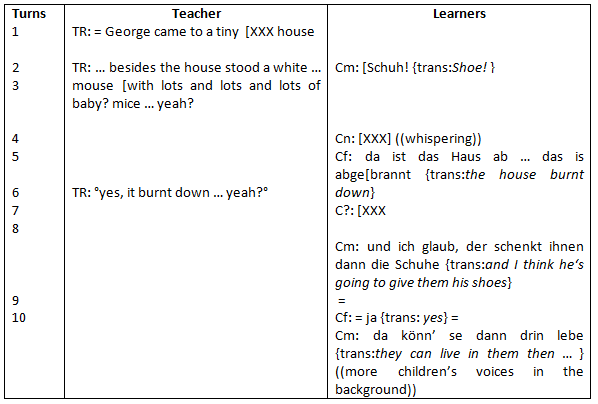

At the end of this episode with the giraffe, the children have experienced all the recurring narrative features: the problem in the form of an animal in need, the problem’s solution which involves George giving away one piece of his new clothing, the accompanying dialogue and song. However, in the following episode with the goat, children do not yet offer any comments on future events. It is only after experiencing the narrative pattern one more time that the children start making accurate predictions as Extract 3 on the following page illustrates.

This extract is related to the episode with the mouse family on double spread 7. The teacher here is immediately interrupted by the children who want to express what they see – clearly a sign of high levels of engagement. The children are busy constructing meaning from what they are looking at (2, 5), and predicting what might happen next using their knowledge about the narrative structure (8-10). Rather than waiting for a response from the teacher, they now seem to continue their line of thought unprompted. Before listening to this part of the story, they have constructed a version of the following events, which is accurate and does not rely on an understanding of the text they are going to be presented with.

The impact of the pictures on reaching an understanding of the plot is of great significance: they provide a scaffolding device that helps the children sustain interest. Rich language that would otherwise be incomprehensible can be decoded enabling the children to experience extended and complex discourse in the foreign language. [End of Page 31]

Apart from some follow-up activities such as a matching pairs task on George’s song and the writing of a card to say thank you to someone, George’s song was practised in different ways involving copying the teacher’s language and joint speaking in the English lesson the following week, which was the last lesson before the Easter Holidays. The story was not read aloud again. Thus, the children’s first encounter with the picturebook was also the only time the children experienced the whole text in the classroom. Furthermore, the children were unlikely to have come across the English version outside school.

Extract 3, Storytelling Session The Smartest Giant in Town, March 2009

Interviews with children

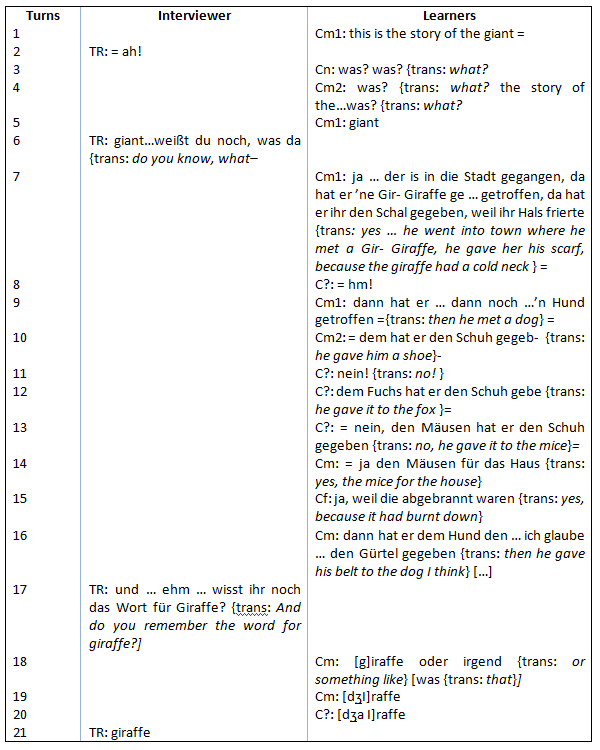

In two of the three interviews conducted twelve months later, three cards showing a different scene from The Smartest Giant in Town were chosen by children to talk about. In each case, individual children displayed a partial knowledge of the storyline as shown in Extract 4.

There is a bewildered ‘what?’ coming from more than one child (3, 4). However, one child does remember, and his comment acts as a prompt (7). The others start to [End of Page 32] reactivate their knowledge as well and together the children jointly reconstruct the storyline helping each other out as they go along (9-17).

Extract 4: Interview with Children, March 2010 [End of Page 33]

In these extracts, the percentage of child talk is higher than during the storytelling session, and children clearly respond to each other’s remarks (7-16). There is also some English embedded in the children’s responses (1, 4, 18-20). One child remembers the English title of the picturebook (1), another picks up parts of it, but does not seem to recognize the word ‘giant’ (4). Later on, in turn 7, a child refers to ‘giraffe’ using its German pronunciation, then again in turns 18-20, the children try to remember the correct pronunciation of the word ‘giraffe’, but they have difficulties, which is something that also occurred in the other interview during which cards featuring scenes from The Smartest Giant in Town were chosen.

Summary of Findings

Children’s response to the picturebook

One finding that can be drawn from the analysis of classroom discourse during the storytelling session with The Smartest Giant in Town is that children’s verbal responses demonstrate the children’s high level of interest in the picturebook. They responded by expressing astonishment at the visual stimuli on turning the page, which is reminiscent of Bader’s (1976) description of a picturebook as an art form that ‘hinges on the interdependence of pictures and words, on the simultaneous display of two facing pages, and on the drama of the turning page’ (1976, p. 1). The picturebook triggered interest in the children, which motivated them to stay attentive and engaged in constructing meaning and discovering more about the story, which was evident in their assumptions about the developing narrative.

Pictorial representation and children’s understanding of the story

The extracts from classroom discourse show that learners used visual clues to understand the plot, and once they unlocked the narrative code, the children in this study also made accurate predictions about the evolving storyline. The pictorial representation acted as a scaffolding device enabling them to make sense of a story told in the foreign language, although the complexity and richness of the language used in the picturebook was well beyond their command of the foreign language at the time. However, the visual images not [End of Page 34] only led to the learners’ following the plot and actively constructing meaning from them, they also encouraged learners to tolerate extended input in the foreign language. Exposure to extended input in the foreign language, however, has been found lacking in secondary EFL classrooms in one of the recent studies on CLIL classrooms (Dalton-Puffer, 2007). In her study, Dalton-Puffer argues convincingly that if we want students to make extended statements and be able to talk about complex concepts, students need to be exposed to extensive input of the same sort. Storytelling sessions, in which primary school children listen attentively for 15 or 20 minutes, could be seen as a very first step in that direction. Picturebook reading can help to prepare students for extended and complex classroom talk and may also lay the foundations for rich output.

Longer-term impact of first encounter with the picturebook

The analysis of interview data has shown that there was some longer-term impact of the first encounter with the picturebook. On seeing pictures depicting scenes from The Smartest Giant in Town, children were able to jointly reconstruct the plot 12 months after the storytelling session. If children can successfully retrieve the storyline and therefore the situation in which words in the foreign language have been used, they are equipped with a meaningful context that will support their vocabulary learning as well. Provided that the teacher creates opportunities for the children to read the story again and to notice new words (Nation, 2001; Schmidt & Frota, 1986), children are very likely to expand their vocabulary as has been found in L2 research (Elley and Mangubhai, 1983).

Implications for teaching

One conclusion that can be drawn from this study with regard to teaching is that for any visible advances of word learning, The Smartest Giant in Town would have to be read numerous times. Would children be bored with repeated encounters of the same picturebook? What we have seen by looking at The Smartest Giant in Town is that picturebooks can provide a rich visual experience. Visual images may go beyond the meaning of the text, may question the events as told in the text, and they may add new layers of meaning (Mariott, 1998). There is a lot to discover and in this picturebook, in particular, there are other fairy tale characters roaming the streets in the illustrations. [End of Page 35] Accepting children’s comments, which stray from the verbal narrative, but which are related to these illustrations, means highlighting intertextual connections. This will sensitize our learners to the fact that texts very often refer to other texts. If we can get primary school children to understand this, we would help them to be better readers at secondary level. We would add a contextual dimension to our teaching – something that Kramsch (1993) suggests is needed to develop fluency in reading: ‘If it is the ability to recognize prior texts that makes for fluency in reading, then teaching reading in a foreign language requires a contextual dimension that is lacking in most traditional approaches’ (Kramsch, 1993, p. 122). Our foreign language learners need to be able to identify intertextual links in texts written in the foreign language and they have to learn how to interpret them within the context of the foreign culture.

In this way, picturebooks can create affordances in the foreign language classroom (van Lier, 2004) and can contribute to the learning process provided that we remember that reading picturebooks in the classroom can be a joyful enterprise, and that the illustrations and the children’s L1 can contribute to the language learning experience.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all the teachers and children who invited me into their classrooms, and to my supervisor Geoff Hall for his comments on this paper.

Bibliography

Donaldson, J. & Scheffler, A. (2002). The Smartest Giant in Town. London: Macmillan.

London, J. & Remkiewicz, F. (1994). Froggy Gets Dressed. New York, London, Victoria, Toronto and Auckland: Puffin.

References

Arizpe, E. & Styles, M. (2003). Children Reading Pictures. Interpreting Visual Texts. Abingdon: Routledge.

BAAL. (2006). Recommendations on good practice in Applied Linguistics. Retrieved from http://www.baal.org.uk/dox/goodpractice_full.pdf

Bader, B. (1976). American Picturebooks from Noah’s Ark to the Beast Within. New York: Macmillan Publishing. [End of Page 36]

Cameron, D. (2001). Working with Spoken Discourse. London: Sage.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cresswell, J.W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Classrooms, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamin.

Davis, K.A. (1995). Qualitative theory and methods in applied linguistics research. TESOL Quarterly 29:3, 427-453.

Doonan, J. (1993). Looking at Pictures in Picture Books. Bath: Thimble Press.

Drew, I. (2009). Using the early years literacy programme in primary EFL Norwegian classrooms. In M. Nikolov (Ed.), Early Learning of Modern Foreign Languages. Processes and Outcomes. Bristol/Buffalo/Toronto: Multilingual Matters. pp. 108-119.

Elley, W.B. (1989). Vocabulary acquisition from listening to stories. Reading Research Quarterly XXIV:2, 174-187.

Elley, W.B. & Mangubhai, F. (1983). The impact of reading on second language learning. Reading Research Quarterly 19, 53-67.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Mariott, S. (1998). Picture books and the moral imperative. In J. Evans (Ed.), What’s in a Picture? Responding to Illustrations in Picture Books. London: Sage. pp. 1-24.

Moon, J. (2000). Children Learning English. Oxford: Macmillan Heinemann.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ochs, E. (1979). Transcription as theory. In E. Ochs & B. Schieffelin (Eds.), Developmental Pragmatics 10:1, 43-72.

Rebenstorff, H. (2009). Story Circle: The Smartest Giant in Town. Englisches Literaturprojekt. 3.-4. Klasse. Kempen: BVK.

Schmidt, R.W. & Frota, S. (1986). Developing basic conversational ability in a second language: a case study of an adult learner of Portuguese. In R. Day (Ed.), Talking to Learn: Conversation in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. pp. 237-326. [End of Page 37]

van Lier, L. (2004). The Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning: A Sociocultural Perspective. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Watson-Gegeo, K.A. (1988). Ethnographic inquiry into second language acquisition and instruction. Paper presented at the TESOL Convention, 9 March, Chicago. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal

Appendix

Transcription conventions (adapted from Dalton-Puffer, 2007):

{trans: tailor English translation of an utterance

… natural occurring pause within utterances

… … deliberate or prolonged pause

[…] transcription has been shortened

((whispering)) additional information about the style of the utterance or the specific situation

= latching (as one speaker stops, another continues)

? rising intonation

! strong emphasis and falling intonation

. falling intonation

, low rising intonation suggesting imminent continuation

but- abrupt cut-off

°red° decreased volume

again marked stress

[v]here phonetic transcription

XXX unintelligible speech

(shop) utterance that is difficult to recognize

Y used instead of a participant’s/speaker’s name

[ onset of simultaneous speech

Capital letters are used for individual words that need to be capitalized according to English or German spelling rules. Capitalization is not used at the beginning of sentences, since the transcription regards speakers’ contributions as utterances rather than grammatical sentences.

[End of Page 38]