|

Intercultural Education, Picturebooks and Refugees: Approaches for Language Teachers

|

Download PDF |

Abstract

Picturebooks can be used as a means of teaching a range of intercultural issues as well as enriching learners’ linguistic and literacy skills. As windows and mirrors, picturebooks can be a powerful vehicle in the classroom in terms of intercultural education for all learners, including those working through the medium of a second language. This article explores the potential of teaching the topic of refugees through picturebooks. While developing the traditional forms of literacy, reading and writing, strategies can also be used to promote critical literacies and intercultural education. Critical multicultural analysis of these picturebooks examines the complex web of power in our society, the interconnected systems of race, class and gender and how they work together. A framework is presented for analysing one picturebook through a series of activities that help learners and teachers to critically interrogate the topic of refugees with empathy and understanding.

Keywords: refugees, asylum seekers, picturebooks, intercultural education, critical multicultural education

Anne Dolan (PhD) is a lecturer in primary geography education at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, Ireland. Her research interests include primary geography, use of children’s literature in education, participatory approaches to education and lifelong learning. She is the author of You, Me and Diversity: the potential of picturebooks for teaching development and intercultural education. [End of Page 92]

Introduction

Within the intercultural theme of migration, there has been a significant increase in children’s literature that deals with the issue of seeking asylum in a foreign country (Hope, 2008). Refugees are defined according to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention as those who have fled their country and are unable to return due to a ‘well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion’. An ‘asylum seeker’ is someone who is seeking protection but whose claim for refugee status has not yet been assessed. While it is important for asylum seekers and refugees to see their stories feature in classrooms, it is also important for indigenous learners to hear these stories and to learn about the experiences of others. These stories are important for showing that refugee children are ordinary children in extraordinary circumstances (Hope, 2008).

Quality picturebooks facilitate the development of language learning: linguistic abilities and communication skills. They have the capacity to enhance moral reasoning skills, emotional intelligence and empathy by humanizing the teaching of English (Ghosn, 2013). Picturebooks can introduce first language (L1) and second language (L2) learners to a range of complex issues in an accessible manner. In the case of L2 learners, who are often older when they are introduced to a second language, they are ready developmentally and cognitively for the complex social issues portrayed in some picturebooks. This article presents the potential of teaching the topic of refugees through picturebooks. The picturebooks shared allow teachers to develop the traditional forms of literacy, i.e. reading and writing. However, a more critical exploration of the portrayal of refugees in picturebooks also enables teachers to promote intercultural education and to develop critical literacies in the classroom.

Intercultural Education

Intercultural education aims to enable the child to develop as a social being through living and co-operating with others, thus contributing to the development of a cohesive multicultural society. It is an important part of every child’s educational experience [End of Page 93] whether the child is in a school characterised by ethnic diversity, in a predominantly mono-ethnic school, or whether the child is from the dominant or minority culture. Intercultural education has two key dimensions. First, it is an education that respects, celebrates and recognises the normality of diversity in all areas of human life. It sensitises the learner to the idea that humans have naturally developed a range of different ways of life, customs and worldviews and that this breath of human life enriches all of us. Second, it is an education that promotes equality and human rights, challenges unfair discrimination and promotes the values upon which equality is based (NCCA, 2005, p. 3). On the basis of a review of key scholars in intercultural education and global education, Short (2009) defines intercultural education as an orientation in which learners:

- explore their cultural identities and develop a conceptual understanding of culture;

- develop an awareness and respect for different cultural perspectives as well as the commonality of human experience;

- learn about issues that have personal, local and global relevance and significance;

- value the diversity of cultures and perspectives within the world;

- demonstrate responsibility and commitment to making a difference in the world;

- develop into inquiring, knowledgeable, and caring human beings who take action to create a better and more just world.

Numerous authors have argued that a considered use of multicultural literature in the classroom has the potential to promote intercultural competencies and to equip students to live in an increasingly diverse society (see Dolan, 2014). Language and talk are two fundamental aspects of intercultural education. In a L2 classroom, multicultural literature can serve the dual functions of language development and an appreciation of social justice issues.

Refugees

Today there are refugees in countries all over the world. Many people are not able to avail of the protection of their state and therefore require the protection of the global community. According to the UN Refugee Agency, there are more than 15 million refugees in the world today. Refugees are a reminder of the failure of societies to exist in [End of Page 94] peace and our responsibility to help those forced to flee. Flight often follows an abuse and violation of human rights as well as various forms of social breakdown, including war. These issues are linked to concepts such as justice, equality, tolerance, freedom and minority rights. Refugee and asylum-seeker issues are constantly in the media, yet many people are unaware of the reasons why people seek refuge in a new country. Sometimes, the media misrepresents migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, creating stereotypes and fuelling myths and misunderstandings. At a time when one in every 100 people in the world has been forced to flee persecution, violence or war, it is important for all citizens, including our young learners, to understand the complex issue of seeking refuge.

Picturebooks Featuring Refugee Stories

Picturebooks about refugees and asylum seekers address a range of universal emotions, including fear, grief and confusion. Several picturebooks pay homage to the resilience of children placed in difficult situations. These books provide ideal teaching opportunities for exploring issues such as compassion, empathy, tolerance, justice, conflict resolution and a respect for human rights. Reasons why refuge and asylum are sought are often misunderstood and many people do not realise how much suffering is endured by asylum seekers and refugees including children. With a view to highlighting a number of titles which fall into the category of picturebooks about refugees and asylum seekers, I will briefly describe six titles which could be suitable for L2 learners approximately 12 years old and above.

Picturebook 1: The Colour of Home

The Colour of Home (Hoffman & Littlewood, 2002) tells the story of Hassan, a child refugee from Somalia, who has witnessed things no child should ever see. When he arrives in England, everything is so different that he is unable to respond to his new classmates’ friendliness why not check here. His teacher invites him to paint a picture and Hassan is able to communicate his experiences in Somalia by first painting bright images related to happy [End of Page 95] memories, which are then spoiled by the representation of his home set afire and his uncle shot to death. Slowly, through the picture and with the help of a translator, his teacher and classmates begin to understand his story and help him build a new life a long way from his first home. Vibrant watercolour, imitating the bright and happy colours associated with Somalian light and its colourful fabrics, contrasts with darker more menacing hues. Red and black represent anger and war, various tones of brown and grey help the reader see Hassan’s sadness and loss. The verbal text is permeated with both descriptions and dialogue and contains no repetition, but is easy enough for learners who are at A2 level of English; in most cases, the illustrations support the readers’ understanding of the words.

Picturebook 2: The Silence Seeker

Another perspective on asylum seekers is provided in The Silence Seeker (Morley & Pearce, 2009). Joe is a small boy living in a city somewhere in England. The story is narrated in the first person, and describes Joe’s quest to find a quiet place for his new neighbour, who, according to his mother, is an asylum seeker. Joe thinks the boy is a ‘silence seeker’, especially when Mum tells him he needs peace and quiet. The story shows a friendship developing between the two boys as Joe comes to realise that he cannot find a peaceful and quiet place for his new friend. Young readers are introduced to the threats and tensions that make Joe’s search for silence so difficult, such as noisy teenagers or grumbling homeless people. Joe’s new friend disappears as quickly as he has arrived and Joe is left wondering about his noisy city and the importance of silence.

The illustrations, digitally created, show Joe’s busy urban neighbourhood with roadworks, flyovers and overhead airplanes. The reader can almost hear the city noises and see the flashing lights. The verbal text is simpler than that of the previous picturebook, and from Joe’s relentless quest for silence, repetition emerges in both the visual and the accompanying verbal text. Again this would be suitable for A2-level learners with ample opportunity for discussion around the reasons Joe’s ‘silence seeker’ sits on the step with [End of Page 96] his eyes closed and doesn’t speak, as well as the problems associated with the characters that disrupt Joe’s world, such as the homeless, jobless youths and noisy teenagers.

Picturebook 3: Gervelie’s Journey: A Refugee Diary

Gervelie’s Journey: A Refugee Diary (Robinson, Young, & Allan, 2009) is based on the true-life story of Gervelie, who was born in 1995 in the Republic of Congo. Her mother and father had a nice house in a suburb of Brazzaville. When fighting broke out two years after Gervelie’s birth, her father’s political connections put the family in grave danger and they were forced to flee. Gervelie’s Journey follows the family from Congo to the Ivory Coast, and then to Ghana, across Europe, and finally to England. The book also contains some important background information about the Republic of Congo and its recent history.

Narrated in Gervelie’s own voice and illustrated through photographs and watercolours, it gracefully depicts her family’s long journey, life in a new country, and her hopes for the future. The illustrations, which create a scrapbook effect, present Gervelie’s story in a realistic and sensitive manner. While international refugee statistics are difficult to comprehend, this picturebook provides a personal testimony that has the potential to generate empathy and understanding in many classrooms. The verbal text is suitable for learners who have reached B1 level of English.

Picturebook 4: Azzi in Between

Endorsed by Amnesty International, UK, Azzi in Between (2012) was written and illustrated by Sarah Garland after spending time with refugees in New Zealand. Told from a child’s perspective, Azzi in Between is a sensitive story about Azzi and her family, who are forced to flee their country to survive. The cover image for Azzi in Between shows a little girl clutching her teddy bear as she looks cautiously behind her while walking through a war torn landscape. [End of Page 97]

This sets the scene for what is to come, in an unspecified Middle Eastern country at war. The war is depicted in shades of grey that contrast with the bright colours in Azzi’s home life. The impact of the war on the family gradually erupts when Azzi’s father, a doctor, receives a phone call warning the family they must leave. Grandma stays behind, as Azzi and her parents make a hurried departure and begin their terrifying journey. The bewildering newness of everything at their destination, including food, language and school, is exasperated by the fact that Azzi also desperately misses her grandmother. Azzi helps her family to overcome some of their sadness when she plants bean seeds from home in the school garden. With the arrival of Grandma, Azzi settles into her new home and supports family members to become accustomed to their new life.

Presented in graphic novel format with simple sentences under each panel and the occasional dialogue in speech bubbles, the clear, emotive illustrations will support learners at an A2 language level to understand the book’s message. Its central message about the plight of refugees is also informative for adolescents and adults.

Picturebook 5: The Island

The Island (Greder, 2007) presents an interesting perspective on refugees or visitors to a new place. A lone man is washed up on the shores of a remote and fortress-like island. The islanders’ response to the stranger is at first grudgingly accommodating although certainly not kind. Soon their irrational fear of the stranger leads the islanders to send the man back to sea. It is a metaphorical account of the way in which prejudice and fear create artificial barriers between people. Barriers become entrenched over time and can create exclusion zones in the name of self-protection. This book offers insights into why detention centres and refugee camps have become so prevalent throughout the world and why refugees are often greeted with expressions of fear and mistrust.

Using charcoal and dark shades, the ominous illustrations powerfully communicate the emotions of the story. The darker tones against a stark white background convey a frightening and partially symbolic depiction of the treatment of refugees. The restricted [End of Page 98] palette of colours employed by Greder also appears to reflect the limited worldview of the islanders as they struggle to deal with the visitor in their midst. The verbal text is simple, but the illustrations are loaded with visual messages and contradictions, which make this particular picturebook suitable for learners over 15 years old with at least B1 level of English, so they can discuss the depth of meaning found in this haunting picturebook.

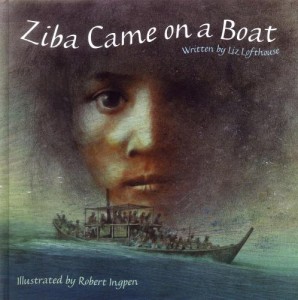

Picturebook 6: Ziba Came on a Boat

Based on actual accounts of Afghani refugees living in Australia, Ziba Came on a Boat (Lofthouse & Ingpen, 2007) tells the story of how a girl and her family experience the desperately high social and economic costs of war and conflict. The story is based on the boat journey to Australia and flashback memories to Ziba’s village life with other family members and friends before escaping war-torn Afghanistan.

The beautiful illustrations by Robert Ingpen capture Ziba’s emotions as she recalls her recent past during the monotonous boat journey: her family working in the village, the coming war and hopes for a better future. Ziba’s memories focus on universal childhood scenes, such as reading schoolbooks and helping her mother set the dinner table, as well as more culturally specific activities, like carrying water jugs back to her mud-brick home. The incongruity between what the lyrical text relates, as it describes her memories in positive terms, and the haunting pictures created in sombre, ochre tones, provides opportunities for interrogation by older learners to discuss the portrayal of refugees through the visual and written messages of the book. This is a picturebook for slightly older learners who have reached B1 level of English.

Comparing and Contrasting Picturebooks

One useful way to critically interrogate the issue of refugees through picturebooks is to compare and contrast how the issues are depicted in a number of books. Among the six picturebooks discussed in this article, Ziba Came on a Boat and Gervelie’s Journey: A [End of Page 99] Refugee Diary are based on real life events. Azzi in Between is a fictional story which draws on the authors own experience of working among refugee families. The Island, The Colour of Home and The Silence Seeker all deal with the theme of refugees through fictional representations. While comparisons of stories and cognitively based reading comprehension strategies often prioritise the written word, it is important to remember that the visual components of picturebooks are equally, if not more, important. These picturebooks about refugees can be compared through the use of their multimodal meaning systems for communicating their stories, that is the use of visual images, design elements and written language. The following guide (adapted from Young & Serafini, 2011, p. 119) helps the reader to consider a range of peritextual features when reviewing picturebooks. This guide can be used by teachers to compare two or more of the selected picturebooks highlighted in this article.

A framework for comparison:

Questions about the different features of picturebooks dealing with refugee stories

1. Cover

- What do you notice on the cover of the picturebook?

- What are the most important features on the cover?

- What is the title of the book? What does this title mean to you?

- Has the book won any awards? Are they displayed on the cover?

- What colours dominate the cover design?

- What is in the foreground? What is in the background? What is the significance of the placement?

- Are there any visual images in the background to consider?

- What refugee clues (if any) are provided on the cover?

2. Representation of asylum seekers and refugees

- Are asylum seekers and/or refugees represented on the cover? How are they portrayed?

- Is the main character looking at you? How does this affect you?

- If the character is looking at you, what might he/she be demanding from you? [End of Page 100]

- Is the character looking away or at someone or something else? How does this affect you?

- Is this asylum seeker or refugee character a historical figure or fictional? How do you know?

3. Setting

- What setting is portrayed on the cover and other illustrations?

- Describe the setting in geographical terms, e.g. find its location on a map.

- When do you think this story is taking place?

- What visual and textual clues are provided on the cover, jacket, and within the authors’ note?

- How is the setting important in the context of this picturebook about refugees?

- How is colour, texture, and motif used to represent the setting of the story?

4. Illustration style

- Are the illustrations realistic, folk art, surreal, or impressionistic?

- How might the style of illustration add to the mood or theme of the book?

- How does the style contribute to the understanding of a refugee’s experience?

5. End pages

- What do you notice about the end pages?

- Do the end pages contain a visual narrative?

- Do the end pages contribute to the visual continuity of the picturebook?

- Do the end pages represent the story of refugees in any way?

6. Book jacket (where book jackets are included)

- What information is contained in the front and back book jacket?

- How does the jacket information (if any) help to establish historical background information for the story?

- How does this information help you to understand the story?

- What clues are given about the historical facts (if any) and fictional aspects being presented? [End of Page 101]

7. Title page

- What information is included on the title page?

- Was a visual image included on the title page?

- Is the image within the story? If so, what is the significance?

- If the image is not within the story, what symbolic meaning does it hold?

Critical Multicultural Analysis in Theory

The use of multicultural children’s literature in the classroom is recommended both for general literacy and for second language education. Multicultural literature can also develop learners’ critical thinking skills, intercultural understanding and lead to a more nuanced understanding of the power relations underpinning our society. Critical literacy is informed by the work of Paulo Freire, who believed that ‘reading the world always precedes reading the word and reading the word implies continually reading the world’ (Freire & Macedo, 1995, p. 35). Critical multicultural analysis comes from the same philosophical family as critical literacies. According to Botelho and Rudman (2009), ‘critical’ refers to maintaining the power relations of class, race and gender at the centre of all investigations concerning children’s literature, thus connecting reading to broader issues of social justice. ‘Multicultural’ refers to the diverse historical and cultural experiences within these layers of power relations. Botelho and Rudman describe critical multicultural analysis as ‘powerful literacy’ because ‘it utilizes literacy for “reading” the discourses that have created us, as well as aligning ourselves with subjectivities (ways of being in the world) and discourses that will mobilize us towards democratic participation in society’ (p. 65).

I concur with McGillis (1997; 2013) that all reading is political. Critical analysis should identify which political or ideological position is presented in a text and should involve the reader clarifying his/her own ideological position. Botelho and Rudman (2009) suggest a multilayered analysis of children’s literature that demonstrates how different lenses shape the interpretation of text. These lenses can include i) a literary approach, involving an examination of the technical aspects of the presentation, e.g. plot, character [End of Page 102] development, use and choice of words, use of text and illustrations; ii) a reader response approach, which involves the reader in the process of co-constructing meaning in conjunction with the text; iii) a feminist approach that critiques literature on the basis of gender, whereby feminine and masculine traits are constructed by society, exploring the way female and male characters are portrayed and the power dimension which underpins the relationships between them; a multicultural approach, referring to how different cultures are depicted; iv) a critical multicultural analysis, which examines the location, construction and negotiation of power and power relations. Reading picturebooks with a critical multicultural lens helps the reader to discover their own power through the ability to make choices, assert an opinion and ask questions.

Critical Multicultural Analysis in Practice

Dolan (2014) proposes a framework of ‘Respect-Understanding-Action’ for promoting critical multicultural analysis. The framework is based on multimodal approaches for learners to structure their responses to the themes presented in a picturebook. The development of respect includes self-respect and respect for others. Teachers provide opportunities for learners to share knowledge about their own cultural background with their classmates. The goal is to create a climate of respect for diversity through learning to listen with kindness and empathy to the experiences of their peers. Through understanding, teachers move from celebrating diversity to an exploration of how diversity has impacted on different groups of people. Learners are exposed to issues related to the history of racism, sexism, classism, homophobia and religious intolerance, and how these forms of oppression have affected different communities. The historical roots of oppression and how they have had an impact upon the lived experiences and material conditions of people today are also made evident. Finally, through action, teachers and learners work on concrete actions which they can deliver in response to an issue discussed in a picturebook. Opportunities are provided for learners to teach others about global and justice issues. This allows them to become advocates by raising awareness amongst peers, teachers, family and community members. [End of Page 103]

‘Respect-Understanding-Action’ in practice

Teachers can build very effective educational programmes and literacy strategies using the picturebooks described in this article and the simple framework of Respect-Understanding–Action. The picturebook Gervelie’s Journey: A Refugee Diary (Robinson, Young & Allan, 2009) is suggested here as an exemplar for curriculum making.

Respect 1: Reflecting on personal life stories. Learners are invited to reflect on their own life stories to date. A range of creative media can be used such as drawings, photography and poetry. Photographs from home can be shared with the class and scrapbooks or a montage can document life stories. Learners may be invited to document some of the highs and lows they have experienced. Personal reflections can be shared with the class in a respectful manner.

Respect 2: Reflecting on our reactions to being told that we had to leave our homes suddenly. Ask learners to decide upon what they would bring with them if they had to leave their homes suddenly. Use the following narration to prompt thinking:

Imagine you are living in a country where war has been declared. Invasion is happening. Bombs are falling. The sound of artillery is rapidly growing louder. You can smell the acrid stink of explosives. People are crying and screaming. You have one minute to stuff your backpack and dash out of your home. What will you take with you?

Learners could make a list and share their ideas through pictures from magazines, collage or written responses. After discussing these items, ask learners to think about what and whom they could not bring with them.

Respect 3: Share the Picturebook: Gervelie’s Journey: A Refugee Diary. Read the story and show the illustrations from the book. Ask learners for their initial reactions.

Respect 4: Questioning Gervelie. Ask students to listen carefully to Gervelie’s story again and to suggest a list of questions they would like to ask her. [End of Page 104]

Respect 5: Respond with drawings. Invite learners to draw the events and characters from Gervelie’s story. They could create a storyboard, drawing the sequence of events as they occur in the story.

Respect 6: Country Fact File. Ask students to conduct research on the Republic of Congo to find out about the conflict that took place in the 1990s. Suggest using headings such as ‘population’, ‘economy’, ‘interesting facts’, ‘culture’, ‘human rights’.

Understanding 1: Create a sculpture. Ask for a volunteer to become a stone to be sculpted. Explain that following directions from the class, learners will create a sculpture of Gervelie. Together students decide which image of Gervelie to sculpt from the story and give instructions. This could be repeated by groups of learners each working with a student to be sculpted. Each group presents its sculpture, justifying what has been created. This should be followed by class discussion about the representation of the sculptures, the decisions which informed their creation and the response of those viewing the sculptures.

Understanding 2: Create a photograph. Ask students to examine the photographs and illustrations in this picturebook and decide on a title. In groups, ask learners to choose a scene from the story, e.g. Gervelie arriving at the airport in Luton, England, and invite leaners to role-play this moment. Instruct them to ‘freeze’ at a certain point to create their own still image from the story. Learners can discuss what might happen next.

Understanding 3: Filmstrip. Ask learners to identify the characters in the story such as Gervelie, her mum, dad and auntie. Divide the class into pairs. One student in each pair is Gervelie and the other becomes one of the characters from the story. Each pair decides on one or two lines of dialogue and an appropriate action. They practice this and show it to the class. Discuss with the class the chronological order of these scenes, and create a sequence of scenes which illustrate the development of Gervelie’s story. These scenes can come together as a virtual filmstrip, which is then preformed for the rest of the class. It can also be recorded on a camcorder for further discussion and analysis.

Understanding 4: A role-play. Many educators have used role-play as a powerful medium for helping learners to empathize with characters in a story and to consider the [End of Page 105] story from their own perspective. Amnesty International has developed a role-play called ‘Time to Flee’ [i], where students watch an immigration scenario. Ask for volunteers to role-play the Immigration Officer and a refugee. The refugees have to decide which items to bring with them. Each refugee has to prove that their story is genuine when they meet the Immigration Officer. The role-play is then followed by a discussion and a re-reading of the Refugee Diary. This activity will generate more insightful discussion and provides an opportunity for learners to discuss feelings and emotions related to the role-play experience.

Understanding 5: Hot Seating. Ask a volunteer to take on the role of Gervelie as the rest of the class then ask questions about her life. This activity builds upon earlier questions (Respect 4: Questioning Gervelie), so questions should now be more critical, insightful and informed.

Understanding 6: Moving Debate. Place signs ‘agree’ and ‘disagree’ on opposite sides of the room. Read out debatable statements about Gervelie’s story such as ‘Gervelie should/should not be allowed to travel to this country’ and ‘People in this country do not know enough about the experiences of refugees’. Ask pupils to stand on the appropriate side of the room according to how they feel about the statement and to explain their decision. If learners are unsure or if they feel they do not have sufficient knowledge then they can stand in the middle of the room. Each learner must be able to articulate a reason for where they choose to stand.

Discuss with learners any actions they would like to take in response to this true story.

Action 1: Project work. Ask learners to identify more information they would like to find out about Gervelie in particular and refugees in general. Discuss how such information can be sourced. Share some of the conclusions from this project with other classes, with parents and with the local media.

Action 2: Write a letter. Write to Gervelie and/or to the author and illustrator, expressing personal reactions to the story. Authors and illustrators are generally interested in feedback from readers. [End of Page 106]

Action 3: Find out about organisations. Find out about organisations which provide services for refugees such as Amnesty International and the Refugee Council. Create a poster for each of these organisations and display it in school corridors.

Action 4: Invite a refugee. If appropriate, invite a locally based refugee into the classroom to tell his/her story and to talk about the experience of settling into this county.

Action 5: Problem Solving. Ask students to create a list of problems identified in Gervelie’s story and to suggest potential solutions. For example, Gervelie found it difficult to settle into her new school in England. Learners could suggest strategies which could be adopted by a class and a school to welcome a new child.

Action 6: Personal reflection. Ask learners if their opinions about refugees have changed in any way after learning about Gervelie’s story. What can be done to help children like Gervelie in their schools, in their country and internationally? What can be done to challenge some of the persistent stereotypes that represent refugees in children’s literature and in society today?

Conclusion

In this article, I have discussed issues relating to multicultural literature through the example of children’s picturebooks about refugee experiences. Hope (2008) argues that such literature provides an ideal context for sharing the stories, feelings and fears. Unfortunately, literature of this type remains marginal in school libraries, on reading lists and in teachers’ planning (Dolan, 2014), both in the L1 and the L2 contexts. This article discusses picturebooks which embrace the refugee experience, serving the education of all learners about experiences of persecution, flight and resettlement, while also reassuring refugee readers that there is new life and hope for the future in an adopted country. Books on this sensitive topic must be well written, properly researched and realistically illustrated. They must depict refugees in a positive, realistic manner.

Multicultural literature can provide a mirror and a window for learners as they view the world through different lenses and reflect upon it in a new light. This article takes the theme of refugees to illustrate the potential of picturebooks as a means of teaching critical [End of Page 107] literacy in a way which recognizes power, the unequal distribution of resources in our society, and the perspective of the protagonist. However, simply increasing students’ access to multicultural literature is not sufficient in itself as a strategy for engaging with global and justice perspectives. In many situations, educators struggle with development concepts and do not move beyond superficial descriptions of lifestyles in exotic places. In some cases, reading more about the world can negatively influence the development of intercultural understanding as negative stereotypes are reinforced. Hence, it is important for educators to choose books with maximum potential for exploring global and justice perspectives. They need to be well-versed themselves in the complexities of these perspectives and the political frameworks underpinning these concepts. Students need to be assisted, encouraged and challenged to engage with the issues raised by picturebooks in an affirmative, effective and age-appropriate manner. Appropriate pedagogical choices need to be made, which include highlighting issues such as perspective, power and voice through questions such as ‘Whose story is being told?’ and ‘Whose story is missing?’ Picturebooks about refugee experiences are an invaluable resource both for L1 and L2 learners. The picturebooks highlighted in this article can contribute to enhancing the development of critical thinking skills and intercultural learning for all learners.

Bibliography

Garland, S. (2012). Azzi in Between. London: Francis Lincoln Children’s Books.

Greder, A. (2007). The Island. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Hoffman, M. (2003). The Colour of Home. K. Littlewood (Illus.). London: Frances Lincoln Ltd.

Lofthouse, L., (2007). Ziba Came on a Boat. R. Ingpen (Illus.). San Diego, CA: Kane Miller Books.

Morley, B. (2009). The Silence Seeker C. Pearce (Illus.). London: Tamarind Publishers.

Robinson, A., & Young, A. (2009). Gervelie’s Journey: A Refugee Diary. J. Allan (Illus.). London: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books. [End of Page 108]

References

Botelho, M. J., & Rudman, M. K. (2009). Critical Multicultural Analysis of Children’s Literature: Mirrors,Windows, and Doors. New York: Routledge.

Dolan, A.M. (2014). You, Me and Diversity: the Potential of Picturebooks for Teaching Development and Intercultural Education. London: IOE Press and Trentham Books.

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Ghosn, I. (2013). Humanizing teaching English to young learners with children’s literature. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal, 1(1), 39-57.

Hope, J. (2008). ‘One day we had to run’: The development of the refugee identity in children’s literature and its function in education. Children’s Literature in Education, 39(4), 295-304.

McGillis, R. (2013). Voices of the Other: Children’s Literature and the Postcolonial Context., New York: Taylor & Francis.

McGillis, R. (1997) Learning to read, reading to learn; or engaging in critical pedagogy. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 22(3), 126-132.

NCCA. (2005). Intercultural Education in the Primary School: Guidelines for Schools. Dublin: NCCA. Available at: http://www.ncca.ie/uploadedfiles/Publications/Intercultural.pdf

Short, K. G. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 47(2), 1-10. Available at: http://wowlit.org/Documents/LangandCultureKitDocs/22CriticallyReadingtheWorld.pdf

Young, S., & Serafini, F. (2011). Comprehension strategies for reading historical fiction picturebooks. The Reading Teacher, 65(2), 115-124. Available at: http://goo.gl/c0pkwd [End of Page 109]