| Intercultural Narratives for In-Depth Learning

Introduced by Alyssa Lowery |

Download PDF |

When I wrote the editorial for Recommended Reads at this time last year on the topic of ‘Children in Zones of Conflict’, I hoped so fervently that the historical moment in which we then found ourselves would be short-lived. Now, the level of conflict and unease in our global community seems to have multiplied substantially, and we global citizens find ourselves facing an uncertain future. The political, historical, and social realities of other nations and cultures are indelibly fixed in our consciousness, further cementing the importance of intercultural education as part of the English curriculum. Aptly, Janice Bland emphasizes the integral place of ‘compelling stories, with opportunities for different cultural perspectives’ in ‘help[ing] students’ imagination, creativity and critical literacy to work outside of the constraining ideological, cultural context of a specific classroom and social group’ (2022, p. 228).

This issue is the second to draw on contributions from the 2024 Reading for In-Depth Learning (RidEL) Conference in Bodø, Norway, where several presenters shared work related to intercultural competence and literature. The four recommended reads highlighted here offer a diverse and thought-provoking journey into intercultural narratives that challenge and deepen our understanding of humanity. From historical fiction to community-driven picturebooks, these texts present stories that move beyond mere representation and instead invite readers to engage critically and empathetically with the lived experiences of others through Byram’s dimensions of intercultural citizenship: ‘savoir être (attitudes of curiosity and inquisitiveness), savoirs (knowledge of the ways of life in a given society or context…), savoir comprendre (skills of interpreting and relating those savoirs), savoir apprendre/savoir faire (skills of discovery and interaction) and savoir s’engager (critical cultural awareness)’ (Porto, 2017). In choosing to focus on intercultural narratives for deep reading, we acknowledge both the transformative potential of literature and the necessity of guiding students through stories that may challenge their assumptions or elicit strong emotional responses. Each of the featured books in this issue uniquely balances the gravity of difficult themes with the enduring hope that arises from human connection, community, and resistance.

Warren Binford and Michael Garcia Bochenek’s Hear My Voice/Escucha mi Voz is a powerful bilingual picturebook that documents the harrowing experiences of child refugees detained at the southern border of the United States. Through first-hand testimonies accompanied by evocative illustrations, the book highlights the crisis and voices of children faced with the dehumanizing experience of detention. As Sissil Lea Heggernes points out, this text is not just a documentation of suffering but a call to reflect on how we engage with stories of displacement in the classroom. In fostering critical and visual literacy, students can better understand the intersection of human rights and narrative agency, grappling with questions of representation and empathy.

The Nakano Thrift Shop by Hiromi Kawakami, recommended by Tara McIlroy, offers a contrasting yet equally profound exploration of everyday life in Tokyo. Through the mundane interactions at a second-hand shop, the novel subtly unpacks themes of friendship, loss, and resilience. The ordinary becomes a vessel for deep reflection, making it an excellent text for encouraging learners to consider how intercultural literature can evoke both familiarity and dissonance. The text’s reflective nature promotes critical engagement while also allowing students to experience the immersive quality of ‘reading as transportation’ (Stockwell, 2009).

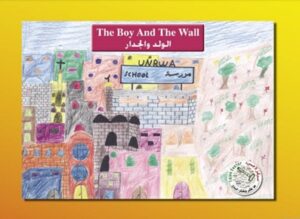

From Palestine, Amahl Bishara’s The Boy and the Wall offers a strikingly different perspective, as children’s voices blend with visual storytelling to narrate life in the Aida Refugee Camp. Nayr Ibrahim’s recommendation highlights how the book’s dual-language presentation and community-driven creation give it a unique power to convey both resilience and resistance. The narrative’s structure, moving from freedom to enclosure, challenges readers to confront the reality of children growing up behind walls while maintaining a spirit of imagination and agency.

Finally, Winifred Conkling’s Sylvia & Aki takes us to mid-twentieth-century America, where two girls – one of Mexican descent and one Japanese American – find their lives intertwined by the injustices of segregation and internment. Through her careful blend of historical accuracy and emotional resonance, Conkling creates a space for readers to confront the impact of discriminatory policies while connecting to the lived realities of the protagonists. The story serves as a compelling reminder that intercultural narratives not only recount past injustices but also illuminate ongoing struggles for equity and inclusion.

Together, these texts remind us that intercultural narratives are more than stories from distant places – they are mirrors reflecting our collective humanity. By inviting learners to read deeply and think critically about these stories, we foster not only linguistic competence but also intercultural awareness and a commitment to justice. As you explore the recommendations in this issue, I hope you will find inspiration to integrate these narratives into your own teaching practice, challenging your students to read both widely and deeply.

References

Bland, J. (2022). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury Academic.

Porto, M. (2017). ‘Yo antes no reciclaba y esto me cambio por completo la consiencia’: Intercultural citizenship education in the English classroom. Education 3-13, 46(3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1259247

Stockwell, P. (2009). Texture: a cognitive aesthetics of reading. Edinburgh University Press.

Binford, Warren & Bochenek, Michael Garcia (2021)

Hear My Voice/Escucha Mi Voz

Workman Publishing Company

Recommended by Sissil Lea Heggernes

Hear my Voice/Escucha mi Voz (Binford & Bochenek, 2021) was on my desk for a month before I managed to open it. I knew it would be a painful read, and it is, but also an important and beautifully illustrated one. Forty-one percent of all refugees globally are between the ages of 0 and 17 (UNHCR, 2022), and this bilingual English/Spanish picturebook documents the situation of child and young adult refugees detained on the border between the USA and Mexico.

These refugees made headlines when it became known to the world that the first Trump administration routinely detained and separated children from their families. A team of inspectors led by international children’s advocate Warren Binford visited the Clint Detention Facility in Texas to oversee the human rights situation. The visits resulted in this book where the words are rendered verbatim from interviews with sixty-one Latinx children and young adult refugees. Their experiences are brought to life through pictures by seventeen Latinx illustrators.

The peritext of Hear my Voice/Escucha mi Voz provides information about the rights of child immigrants in detention, reflection questions for readers and suggestions for how to help. While picturebooks frequently introduce the main character on the first spread with a picture, the reader is here met by an illustration of a name list. The names are blotted out, leaving only the initial letter, reminiscent of a system where the children are anonymized and dehumanized (Heggernes, 2023). Yuyi Morales’s impactful illustration on the second spread depicts six children, the oldest one at seventeen carrying her infant son of six months. They hold the reader’s gaze as they state their ages. The consecutive spreads show families fleeing from gang violence, crossing the border only to be kept in unsanitary and overcrowded cells where the children go hungry. A particularly heartbreaking illustration by Salomón Duarte Granados shows a girl being torn apart from her sister, leaving her ‘all alone’ (Binford & Bochenek, 2021). However, it also shows the children’s attempts at taking care of one another, and their hopes and dreams for the future.

Even if the book provides brutal glimpses into the children’s experiences, Binford still describes it as a children’s book, as it attempts to capture the child perspective. It requires mediation by thoughtful adults, for example English language teachers working with democracy and citizenship with intermediate and advanced learners. The rich and varied illustrations lend themselves to critical analysis of the power balance between the young refugees and the representatives of the system. Such an activity can increase both the learners’ critical and visual literacy. However, while reading literature about challenging circumstances, children also need to maintain hope that change is possible (McAdam et al., 2020). Learners can consequently be encouraged to consider how the young refugees take agency and attempt to remedy their own situation. Published in 2021, the recent political development both in the USA and globally testifies to the urgency of hearing the voices of children who are forced to flee from their homes. Proceeds from the sale of Hear my Voice/Escucha mi Voz benefit children who migrate.

Bibliography

Binford, Warren & Bochenek, Michael G. (2021). Hear My Voice/Escucha mi voz: The Testimonies of Children Detained at the Southern Border of the United States. Workman Publishing Company.

References

Heggernes, S. L. (2023). Enacting democracy with refugee voices through a picturebook in English language teaching. In O. B. Øien, S. L. Heggernes, & A. M. F. Karlsen (Eds.), Flerstemmige perspektiver i norsk utdanningsforskning : spenninger og muligheter (pp. 11–31). Cappelen Damm akademisk. → https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23865/noasp.212

McAdam, J. E., Ghaida, S. A., Arizpe, E., Hirsu, L., & Motawy, Y. (2020). Children’s literature in critical contexts of displacement: Exploring the value of hope. Education sciences, 10(12), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120383

UNHCR. (2022). Global trends report. https://www.unhcr.org/media/40152

|

Sissil Lea Heggernes is Associate Professor in English Language Teaching at Oslo Metropolitan University. Her PhD study from 2021 explores English language students’ intercultural learning through texts, with a particular focus on the role of picturebooks. Her research interests include children’s literature, visual analysis, critical thinking, dialogic learning, and language teachers’ professional development. |

Kawakami, Hiromi (2017)

Translated by Allison Markin Powell

The Nakano Thrift Shop

New York: Europa Editions

Recommended by Tara McIlroy

The Nakano Thrift Shop by Hiromi Kawakami (2017) is a book suitable for teen readers looking for an immersive and reflective reading experience. The book explores themes of friendship, growing and relationships while also addressing bullying, gender dynamics, anxiety, regret and ageism. The interactions between characters in the story may lead to lasting friendships, love, or, as in real life, unexpected outcomes. International readers of the English translation may be intrigued by curious details about daily life in Tokyo, including its food and culture.

The three main characters of the story are Mr Nakano, the thrift shop owner; Hitomi, the sales assistant; and Takeo, the delivery driver. Seen through the eyes of Hitomi, the book follows their daily interactions working together in a second-hand shop in a Tokyo suburb. The narrative is filled with misinterpretations, missing details, and moments that could have unfolded differently. Contemporary readers will perhaps see their own friendships and interactions with others reflected in the ordinary lives of this novel.

Those who describe themselves as keen readers often find themselves lost in books, forgetting time and place as they read. This experience, drawing on Gerrig (1993), is what Stockwell (2009) refers to as the reading metaphor ‘reading as transportation’, occurring when readers feel completely carried away by a book. Further exploring the concept of metaphors of reading, Nuttall and Harrison (2020) identify ‘reading as eating’ as a way in which readers describe eagerly devouring enjoyable texts. Reviewing Goodreads comments for metaphors of reading can show how books are enjoyed or disliked by readers. As an instructional strategy for prompting discussions of reading preferences and critique, reviewing reader comments can help learners express their own ideas and preferences.

When considering using The Nakano Thrift Shop (2017) in the language classroom, teachers could consider excerpts of the text as examples of descriptive writing, cultural artefacts or language study. The novel, in the English version, can be used for in-class discussions or as an independent reading assignment. As the novel has been translated into different languages from the original Japanese, comparison of versions is possible as a classroom exercise. Course design could consider different aspects of literary competences (Alter & Ratheiser, 2019) including empathetic, aesthetic and stylistic, cultural and discursive as well as interpretative competences. Cultural and discursive competence can, for instance, mean reviewing and critical reviews, which can be developed through analyzing literary reviews and reader responses on platforms such as Goodreads.

Interpretative competence can be fostered by inviting students to infer meaning and consider what is left ‘unsaid’ in a text. For example, teachers could ask learners to try and understand the thinking of the protagonists from different perspectives at different points in the story, considering and questioning the decisions of characters.

Critical reading is part of the Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework, suitable with this text with learners of intermediate levels and above. One potential intertextual approach could involve comparing The Nakano Thrift Shop with other contemporary Japanese fiction, such as Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata or Ms Ice Sandwich by Mieko Kawakami. Post-reading activities might include discussions on the global popularity of Japanese fiction in translation, as well as broader conversations on literary trends and cross-cultural storytelling.

The Nakano Thrift Shop offers a reflective and culturally rich reading experience for international readers, making it an excellent choice for both independent and classroom reading. The book’s exploration of human relationships and accessible narrative style allows readers to connect with its characters and themes in meaningful ways. With its potential for literary discussion and cross-cultural insights, the novel is a valuable addition to any reading list for teen and young adult readers.

Bibliography

Kawakami, Hiromi, trans. Allison M. Powell (2017). The Nakano Thrift Shop. Europa Editions.

Kawakami, Mieko, trans. Louise H. Kawai (2018). Ms Ice Sandwich. Pushkin Press.

Murata, Sayaka, trans. Ginny T. Takemori (2018). Convenience Store Woman. Granta Books.

References

Alter, G. & Ratheiser, U. (2019). A new model of literary competences and the revised CEFR descriptors, ELT Journal, 73(4), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccz024

ELLiL Project Partners (2023). Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework. English Language and Literature – In-Depth Learning. https://site.nord.no/ellil/reading-for-in-depth-learning/

Gerrig, R. J. (1993). Experiencing narrative worlds: On the psychological activities of reading. Yale University Press.

Nuttall, L., & Harrison, C. (2020). Wolfing down the Twilight series: Metaphors for reading in online reviews. In H. Ringrow & S. Pihlaja (Eds.), Contemporary media stylistics (pp. 35–60). Bloomsbury.

Stockwell, P. (2009). Texture: a cognitive aesthetics of reading. Edinburgh University Press.

| Tara McIlroy (PhD) is Associate Professor at the Center for Foreign Language Education and Research, Rikkyo University, Tokyo. Previously a high school English literature teacher, she is currently an active practitioner and researcher interested in developing language courses using literature. |

Bishara, Amahl (2005)

The Boy and the Wall

Bethlehem, Palestine: Lajee Center

Recommended by Nayr Ibrahim

The Boy and the Wall / لصبي والجدار (2005) is a dual language English-Arabic community published picturebook written by Amahl Bishara, with Nidal al-Azraq, and illustrated by the children at the Lajee Centre in the Aida Refugee Camp in Bethlehem, Palestine. This picturebook is a collective effort between the author and the refugee children, giving the children equal status as creators, and thus positioning the child illustrators as central to the narrative of their own lived experiences. The Boy and the Wall was the winner of the Psychologists for Social Responsibility’s Josephine ‘Scout’ Wollman Fuller Award, 2008. Bishara’s acceptance speech at the award ceremony highlights the importance of giving children a sense of purpose (the older teenagers created the book for the young children) and agency in that ‘all of this work gave the children themselves the tools to be the leaders and caregivers in the community’.

The story describes how a boy’s life is affected by the construction of what has come to be known as ‘the separation or apartheid wall’, which started in 2004 near the camp. The picturebook includes twelve colourful illustrations created by children in a combination of drawing and collage, including the front cover. The children’s illustrations start with an open, natural space, where children ‘play soccer, find turtles, and pick flowers’. This space gradually becomes dominated by the wall, depicted on every illustrated page. Despite its menacing presence, it slowly blends into the illustrations. However, the child characters, created with collage, playfully and actively acknowledge and transcend the wall as they fly colourful kites that can be seen beyond the wall, dancing so loudly that they can be heard over the wall, and read books in an airy school community that make them travel, through their imaginations, beyond their enclosed realities. The text is a rhythmic dialogue between a mother and her child as the boy tries to find solutions for overcoming the caging in (Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2019) of his play spaces by the concrete wall: ‘Perhaps I will become an onion patch, so that when the soldiers throw tear gas, my friends can be soothed by my onions’. ‘If you become an onion patch’, said his mother, ‘I will become the warm, rich soil in which you grow’. The mother’s recurrent conditional statements maintain an undercurrent of displacement, while demonstrating her steadfast love for her son and for Palestinian culture and traditions.

Children’s literature has engaged with the refugee experience through the challenging themes of displacement, separation from the land, belonging and non-belonging, and its socio-emotional/psychological effects (Weir, Khan & Marmot, 2023), while simultaneously promoting ‘empathy and the understanding of suffering and the imperative to flee’ (Bland, 2022, p. 101). However, this book does not fall into despair. Despite the lack of facial features of the child characters, creating a distance with the reader, they fill the space with their normal child play, skipping, running, dancing, climbing, transforming these everyday activities into an affirmation of belonging and overcoming. This creative narrative of resistance allows them to escape the cage emotionally, visually, and narratively, yet there is no resolution and no closure. What is special, and simultaneously contradictory about this picturebook, is that it is anchored in a community that is displaced in its place of belonging, with a wide-reaching message of resilience and hope.

Classroom-based activities can include language development for story engagement, such as using the first conditional to continue the rhythmic dialogue structure between mother and child. In pairs, children imagine and role play other play-based, active and aesthetic learning activities that could help them escape the physical enclave in spirit and in imagination. The lack of a neat ending to the story is also an invitation for artistic interactions with the collage, where children can draw facial features reflecting the characters’ emotions, on each page. From an interdisciplinary perspective, a collage art project can include illustrating their invented dialogues and displaying them in the classroom or the school, inviting discussions about children in the refugee crisis. Even though this book is not easily available, through the collection of illustrations by young artists, the presence of Arabic on the page and its representation of internally displaced children, it is a powerful historical and authentic resource of engaging English language learners in discussions of lived resistance (Morrison, 2024).

Bibliography

Bishara, Amahl (2005) The Boy and the Wall / لصبي والجدار. Lajee Centre.

References

Bland, J. (2022). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury.

Morrison, H. (Ed.). (2024). Lived resistance against the war on Palestinian children. University of Georgia Press

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (2019). Incarcerated childhood and the politics of unchilding. Cambridge University Press.

Weir, H., Khan, M. & Marmot, A. (2023) Displaced children’s experience of places and play: A scoping review, Children’s Geographies, 21(3), 502–517.

| Nayr Correia Ibrahim is Associate Professor of English Subject Pedagogy (Nord University), leader of CLELT (Nord Research Group For Children’s Literature in ELT) and on the executive committee of ARCLEN (Association for Research on Children’s Literature in English in Norway). Nayr works with children’s literature through a social justice, multilingual, intercultural and decolonial lens. |

Conkling, Winifred (2013)

Sylvia & Aki

New York: Yearling

Recommended by Alyssa Lowery

Sylvia & Aki (Conkling, 2013) is a historical fiction novella that weaves together the real stories of Sylvia Mendez and Aki Munumitsu, two girls whose lives were deeply affected by racist governmental policies in 1940s America. Sylvia, whose father Gonzalo Mendez is suing the Westminster School District for Mexican children’s rights to attend schools with their White peers, finds her life intersecting with that of Aki Munumitsu when the Mendez family rents the Munumitsu’s asparagus farm while the Munumitsus are interned at Poston Japanese Internment Camp during World War II. The chapters alternate narration between the two girls, bringing the similarities of their experiences to the forefront and offering a compelling look at the costs of inequitable public policy.

Authors of historical fiction must concern themselves with accuracy, described by Laura Saxton (2020) as ‘a text’s adherence to established—or agreed upon—historical fact’ (p. 128), and authenticity, which Saxton describes as primarily concerned with the fictive elements of the genre. The attempt to leave readers with ‘an impression of whether it captures the past’ (Saxton, 2020, p. 128) is made largely through elements of the narrative that ‘imagine that person’s thoughts, motives, emotions, and the minutiae of their lives’, which can be challenging to assess (Saxton, 2020, p. 129). In the case of Sylvia & Aki, readers are in the capable and conscientious hands of Winifred Conkling, a journalist by training who largely writes adult nonfiction and who has made her methodology extremely transparent in the novella’s afterword and bibliography. In addition to several personal interviews with Mendez and Munumitsu, she cites court records (from which the courtroom scenes in the narrative are drawn directly) alongside several articles and books about the era she describes.

The book’s main characters find their lives transformed by prejudice, discrimination, and deep hurt, and their experiences are made accessible by a writing style especially well-suited to English language learners who are just beginning to approach more lengthy books. The chapters themselves are rather short, and the language itself is evocative, but digestible for those with a still-developing English vocabulary. Early in the novel, Sylvia finds Aki’s Japanese doll, hidden away in the bedroom where Sylvia now sleeps. Attempting to mimic the grace of the doll’s hands, she contemplates her memories of the hands of the school secretary who turned her away from registration at Westminster School as well as those of her father who works hard on the asparagus farm. Turning her attention to her own, she muses, ‘Her hands belonged to her and no one else; no two existed like them anywhere on earth. Yet others used their own hands to hold her and her brothers back and even wave them away’ (Conkling, 2013, p. 34). Passages like this one achieve literary symbolism through approachable language, meeting the needs of learners who are ready to engage with the realities of injustice while still developing English language comprehension.

The novella presents an important historical reality that seems especially crucial to study in an era when inequity, division, and injustice are visibly shaping public policy across the globe. In the case of the USA in particular, where this novella is set, it is essential for the world to hold in memory the historical truths that may soon be removed from American classrooms. The true stories of Mendez vs. Westminster, the landmark case that opened the door for the desegregation of American schools, and of the internment of Japanese American citizens who had committed no crimes and faced no juries must be told and acknowledged as a part of the horrible lineage of racism that plagues the nation. Sylvia & Aki offers a fantastic entry point for the intercultural awareness and global citizenship at a time when we as an international community cannot afford to lose either.

Bibliography

Conkling, Winifred (2013). Sylvia & Aki. Yearling.

References

Saxton, L. (2020). A true story: Defining accuracy and authenticity in historical fiction, Rethinking History 24:2, pp. 127–144. DOI: 10.1080/13642529.2020.

| Alyssa Magee Lowery is a former schoolteacher and current Associate Professor of Children’s Literature and Young learners at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Her particular research interests relate to popular media for children, young adults, and families. |