| Teachable Texts: Recommendations for Embracing an Expanded Notion of Text in ELT | Download PDF |

Introduced by David Valente

Readers may notice a change to the title of our regular ‘Recommended Reads’ feature, which for this issue we are calling ‘Teachable Texts’. In the current feature, we focus on a range of recommendations to help teachers to consider and engage deeply with a wider concept of ‘text’. Janice Bland’s (2023) handy glossary in her latest monograph provides an encompassing definition which states that ‘a text is an artefact that is used for communication and carries meaning that is often open to interpretation’ (p. 316). This reflects a contemporary, expanded understanding of text as richly multimodal, transcending any sole reliance on books and thus recognizing the value of learners’ creative encounters with multimodal texts in English language education. Likewise, national curricula in a variety of contexts similarly embrace this notion, exemplified here in Norway’s Curriculum for English,

Language learning takes place in the encounter with texts in English. The concept of text is used in a broad sense: texts can be spoken and written, printed and digital, graphic and artistic, formal and informal, fictional and factual, contemporary and historical. The texts can contain writing, pictures, audio, drawings, graphs, numbers and other forms of expression that are combined to enhance and present a message (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2020, p. 3).

Such a multitude of text types, however, can present challenges for educators as they approach the selection of texts for ELT. Based on six key text selection references, Annika Kolb and Marita Schocker (2021) have developed a useful checklist to support this process, including criteria focused on a text’s content, language, intercultural learning affordances, and its potential to act as a springboard for follow-up tasks. The authors also include a further category which tends to be insufficiently considered in ELT – and yet when selecting multimodal texts is crucial – that is, the text’s aesthetic quality. The contributors to this issue of Children’s Literature in English Language Education have clearly prioritized this category in their selections, which include a television series, a song and music video, an animated film, and a website images collection. When considering the aesthetic quality of texts, Kolb and Shocker (2021, p. 137) provide the following questions for teachers:

- Is the text humorous, moving or surprising through its language, images, animations etc.?

- Does the text inspire the children’s creativity and imagination?

- What literary or cinematic devices (e.g., rhythm, rhyme, contrasts, metaphors, repetition, close-ups, music) does the text contain? Do they support anticipation and memorization and add to the enjoyment of the text?

- What is the quality of the visuals and/or animations? Do they add new levels of meaning beyond the verbal text? Do they expand the understanding of the narrative? Do they inspire discussions?

- Does the text promote multiple literacy?

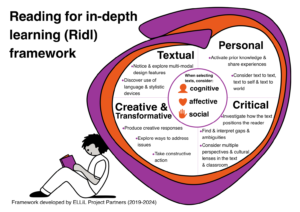

Once suitable texts have been chosen for various school grades, the subsequent challenge relates to teachability and the design of lessons around texts for their English learning affordances. Therefore, it follows that pedagogies are also multimodal, as Lim et al. (2022) highlight, when crafting lessons, educators should engage in ‘weaving together a series of knowledge representations into a cohesive tapestry and in so doing make apt selection of meaning-making resources to design the students’ learning experience’ (p. 1). To help teachers, student teachers and teacher educators to create this ‘cohesive tapestry’, a group of scholars from the English Language and Literature for in-depth Learning project have recently developed a flexible framework for planning lessons around texts (ELLiL Project Partners, 2023). The framework comprises four central dimensions: textual, personal, critical and creative / transformative (see Figure 1). And teacher educators who use this issue’s recommendations during their courses may wish to ask (student) teachers to map the suggested activities to these four dimensions.

Figure 1. Reading for in-depth learning framework

Finally, it is important to highlight that in making these recommendations for beyond-the-book extensions in school contexts, the implication is not that we should replace literary texts. Rather the suggestions demonstrate ways that educators can supplement their work with literary texts through creative connections to the types of texts that children and teenagers encounter in out-of-school contexts. Here, the goal is to implement Werner Delanoy’s (2018) pedagogical proposal of a ‘text ensemble’ whereby diverse perspectives can be fostered through learners’ exposure to and engagement with a collection of narrative texts – literary and otherwise – on a challenging topic or theme. For researchers and teacher educators with an interest in this approach, an upcoming conference which is closely connected to this journal, entitled Reading for in-depth English Learning: Texts in and beyond the classroom (RidEL 2024) would be worthwhile. Please visit the conference website for more information: https://site.nord.no/ridel/

References

Bland, J. (2023). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350190016

Delanoy, W. (2018). Literature in language education: Challenges for theory building. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using literature in English language education: Challenging reading for 8–18 year olds (pp. 141–57). Bloomsbury Academic.

ELLiL Project Partners (2023). Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework. https://site.nord.no/ellil/reading-for-in-depth-learning/

Kolb, A., & Schocker, M. (2021). Teaching English in the primary school. Klett Kallmeyer.

Lim, F. V., Toh, W., & Nguyen, T. T. H. (2022). Multimodality in the English language classroom: A systematic review of literature. Linguistics and Education, 69, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2022.101048

Utdanningsdirektoratet (2020). Læreplan i engelsk. ENG01-04. https://www.udir.no/lk20/eng01-04

|

Oseman, Alice (2022-ongoing) Heartstopper Directed by Euros Lyn, See-Saw Films Recommended by Houman Sadri |

The television series, Heartstopper seems, at first glance, to be an odd text to recommend. This is not because of its subject matter – the love between two secondary school boys and the relationships of the group of teenagers in their orbit is to some extent commonplace in the current YA zeitgeist – nor a result of its intertextual status as a series of hefty graphic novels by Alice Oseman that started life as a periodical webcomic. The real reason that recommending this text initially seems strange is its fundamental ubiquity. The runaway success of the graphic novels led to the commissioning of a Netflix adaptation directed by Euros Lyn – which is, refreshingly, also written by Oseman – and this appears to have granted the tale of Nick, Charlie, and their friends a sort of modern classic status. It is likely that any secondary classroom is already populated by young people who know, or have heard about, this text (or at least its adaptation). The odds are equally high that they have enjoyed it. So why bother?

The simple answer is that unlike what seems to be the case for many YA romances, Heartstopper never settles for the obvious or expected plot beats or contrivances. The more complex answer, though, is that Heartstopper never seems to be addressing a constructed or theoretical audience, as much as it appears to be presenting an idealized version of lived experience. Heartstopper ‘sees’ its audience, and cares about them to boot. This is rare and needs unpacking. Peter Hollindale’s (1997) definition of a children’s author as someone ‘who on purpose or accidentally uses a narrative voice and language that are audible to children’ (p. 29) is important to bear in mind when approaching the text. Nick and Charlie, the protagonists, are at different stages in their understandings of their own sexualities. As the narrative opens, Charlie is out, because of bullying endured the previous year, while Nick is unaware of his bisexuality, and is to all intents and purposes a heterosexual, rugby-playing lad. At this juncture, the reader would be forgiven for expecting explicit bullying to be central to the narrative, and for Nick to be seen to undergo a monomythical ‘Refusal of the Call’ (Campbell, 1993, p. 59) in his own personal hero’s journey. Crucially, neither of these things happen. Certainly, Charlie is treated poorly by certain boys in his year, but the reader is asked to sympathize with both parties (if not equally), and to understand that while such behaviour is recidivist, the putative bully can correct his behaviour. Meanwhile, though volume one of the graphic novel ends with Nick fleeing his first kiss with Charlie (Oseman, 2019, pp. 258-263), this cliff-hanger is resolved very quickly, not to mention romantically, at the start of the next volume (Oseman, 2019, p. 276).

These aspects of the text are important for several reasons. Firstly, and perhaps most tellingly, the undercutting of YA romance tropes and clichés demonstrate Oseman’s determination not only to avoid telling the same old story that her audience has read or watched many times before, but also to actively avoid insulting their intelligence. While YA tropes have gone a long way to help construct the late childhoods of several generations of readers, real life is less likely to fit a formula. Equally, of course, everyone’s sexualities are different, and Nick, Charlie and their circles offer neither easy pigeonholing nor, crucially, the impossibility of evolution. On top of this, the happy, romantic ending to volume two wherein Charlie and Nick are confirmed as a loving couple is not an ending at all: despite the love and support of both his partner and his family, Charlie is still seen to be suffering from an eating disorder. Love does not conquer all, but a support structure is vital, and saves lives. Also important are the supporting characters and their progressions, perhaps most notably the characters of Elle – a newly-transitioned girl – and Tai – her male best friend and romantic interest – whose relationship is never portrayed as anything other than that of two teenagers exploring their feelings for one another, and as such is never sensationalized.

Herein lies both the crux of Heartstopper’s success, and the ways in which it can work in the English subject environment, especially in grades 5-10. Oseman never writes down to her audience: she is writing to herself, about experiences that are universal to young people irrespective of sexual orientation. It is an idealized view, of course, but Oseman believes in love, in romance (in all senses of that word), and in the intrinsic goodness of the universe, even going so far as to promise a happy ending to the story. In a YA landscape in which successive series and trilogies seem to revel in inflicting pain and hardship on their young protagonists, this is refreshing and progressive. More to the point, it allows LGBTQIA+ youth to read texts in which their actual lives are reflected, and which are speaking directly to them, while simultaneously giving young people who have little or no experience of or exposure to anything but the heteronormative an insight into queer life, joy, and the challenges of growing up not straight. Perhaps the best use of Heartstopper in the English language classroom is as a prism through which to observe and understand others, the better to foster empathy, understanding and confidence. Sometimes, as it turns out, the world is a good place.

Bibliography

Oseman, Alice (2019–2021). Heartstopper (Vol. 1–4). Hachette Children’s Books.

References

Campbell, J. (1993). The hero with a thousand faces. Fontana Press.

Hollindale, P. (1997). Signs of childness in children’s books. Thimble Press.

Houman Sadri is an associate professor of English at the University of South-Eastern Norway, where he is currently responsible for the English programme on the 5-year master’s degree. He is the Managing Editor of MAI: Feminism and visual culture (https://maifeminism.com/) and most recently edited a special issue devoted to feminist discourse in comics (https://maifeminism.com/issues/focus-issue-ten-comics-graphic-novels/). He is also a contributor to Key terms in comics studies (Palgrave, 2022).

|

Gambino, Childish (2018) This is America Composed and produced by Donald Glover and Ludwig Göransson RCA Records Recommended by Claire Steele and Sarah Smith |

This is America needs little introduction having amassed more than 876 million views on YouTube. Childish Gambino’s song and music video is a graphic counter-narrative and commentary on American culture, history, and society which skilfully forces the listener-viewer to confront issues connected to race, gun violence, and the toxicity of pop culture. Metaphors and symbolism abound in this powerful call to action which has helped spark conversations about race, society, and politics in the USA and beyond since its release. The video expertly juxtaposes the innocent with the violent (a gospel choir singing and dancing elatedly before being brutally gunned down) to underscore how Black art is used (read: exploited) as a distraction from racism and gun violence. Its genius lies in the blurring of virtual violence (the enjoyment of an entertainment video showing Black people getting shot) and real violence (the reality of gun crime in the USA), which ultimately renders the viewer-listener complicit.

Considering its challenging themes, creative lyrics, and rich visual symbolism This is America is an excellent text to unpack, analyse and interpret in the upper-secondary English language classroom (with learners circa 15 – 17). This thought-provoking music video can be used to prompt a multitude of interpretations and reactions and can enable learners to explore social justice issues while making connections to their own experiences, contexts, and cultures. The video references historical and contemporary events including police brutality, the history of racism and oppression, and the Black Lives Matter movement – through its symbolism of dances / poses, characters, background actions and the abrupt gunshot scenes. In the opening scene for example, Gambino adopts a pose reminiscent of the Jim Crow slave caricature from nineteenth century minstrel shows and shoots a gun wildly. The minstrel shows were a racist depiction of Black slaves, mostly performed by white actors in blackface make-up, which mocked African American cultures. While Gambino dances and entertains us in the foreground, violence and police brutality provide a chilling backdrop. The video scenes exemplify how pop culture perpetuates racist tropes and stigmatizes Black communities, instead of confronting social justice themes such as institutionalized police brutality, and underscores the crucial role of the Black Lives Matter movement in raising awareness of the country’s racist and oppressive history.

The video’s symbolism and visual metaphors can be readily explored with teenagers in the English language classroom using critical thinking and visual literacy analysis to help students situate the social justice issues in a global context. For example, there is a scene that shows teenagers looking down upon the chaos and violence with masks on and recording everything on their cell phones and each time the protagonist shoots a gun, someone comes to gently take it from him, covering it with a red cloth. The entire video is filmed in an old warehouse that looks remarkedly like a prison. As the video’s style combines music / dance, visuals, and lyrics to create a complex, multi-layered text, adolescents have an opportunity to explore different modes of communication and their contributions to meaning making. In ELT particularly, learners can apply visual and media literacy to enhance their language learning, an example being the juxtaposition of beat / rhythm with lyrics, choreography, and visuals in the opening scene. Here the music is cheerful, associated with African chanting, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah… go, go away’ as the protagonist dances playfully to this rhythm. As he moves to the foreground and the camera pans out to him and a guitarist, he strikes the Jim Crow pose, pulls out a gun and shoots. From here the music changes to deep beats, rapping ‘This is America’ with the character now dancing arrogantly.

Overall, the video critiques the USA’s historical and contemporary culture to illuminate its flaws, which can act as a springboard to classroom discussions about social justice, equality, and human rights. There is also space to explore these challenges in other countries, thereby giving learners a window to relate and connect to the topics as global citizens. It is noteworthy that during the past five years, alternative versions of the song and music video have been produced, which include This is … Nigeria / Sierra Leone / Barbados / Malaysia / Iraq / Australia to name several. Learners could collaborate to collate and analyse some of these versions as well as craft a version for their own countries and in turn, question stereotypes and single-story portrayals of nations.

The song’s clever, evocative lyrics offer fertile ground for language learning by engaging students in reflections about Childish Gambino’s views of the lived experiences of Black people, particularly those of Black men in the USA. These verbal descriptions objectify and zoomorphoses Gambino’s subject, ‘You just a Black man in this world. You just a barcode’ and ‘I kenneled him in the backyard. No, probably ain’t life to a dog’. The text, therefore, has huge potential for pedagogical tasks, for example, the mention of barcodes occurs at the end of the video where the protagonist is running scared. In groups, learners can brainstorm how barcodes might relate to Gambino’s commentary on US society / history, as well as the significance of the repetition of the adverb ‘just’. Used in this context, it denotes ‘of a lesser worth than another’ and learners could consider which social groups are pejoratively referred to as ‘just an XYZ person’ in their own contexts. This could lead into a pyramid discussion about ways to help shift this kind of harmful, marginalizing perspective.

Teachers could show learners the following lyrics before they watch the music video, ‘Look how I’m geeking out, I’m so fitted, I’m on Gucci, I’m so pretty…’ and ask them to ponder how the lines might link to the song’s title. Next, working in A/B pairs they watch this specific clip only: Student As look at the dancing (who and how) and Student Bs look at what is happening in the background. After viewing and sharing ideas with their partners, students can contemplate the underlying messages about America. The teacher could then write or draw symbols from the video on the board, for example, a red cloth, the school uniforms, the children recording videos on their cell phones and the two gold chains worn by the protagonist. Here students can consider how the symbols relate to their own ideas about the USA. After playing the video, the teacher can ask students if their thoughts have changed, and why. As an extension task, students could share ideas about what they think would be featured in the foreground and in the background if this music video were made about their own country. Finally, groups could find other music videos (in English and/or their other languages) with themes related to their national contexts to share with the whole class.

If teachers decide to use this music video during upper secondary English lessons, it is important to bear in mind that images of people being shot can be traumatic for some learners. We recommend warning students and parents / caregivers in advance and giving the students a choice about watching while also sharing the pedagogical reasons why this song and music video was selected. The apparent contradictions present in the song / video help convey powerful messages about the dangers of pop culture consumption, in particular its violence and unwillingness to directly tackle social justice issues. We should be exploring such topics in the secondary English language classroom to develop students’ critical thinking skills, to encourage activism, and to help foster greater awareness of the toxic messages and imagery that we are bombarded with daily.

Claire Steele and Sarah Smith are the co-founders and directors of eltonix, an educational consultancy focused on teacher development (www.eltonix.com). They are interested in developing critical and creative thinking, exploring social justice themes in the classroom, and supporting students with special educational needs and disabilities, in particular ADHD. Their publications include Steele, C. & Smith, S. (2021). Through participation to empowerment. English Teaching Professional, 137, 58–60. Sarah (she/her) and Claire (they/them) have worked as teachers and teacher educators in several countries. Sarah is currently based in Greece and Claire is based in Portugal.

|

Caby Hugo, Devise Zoé, Dupriez Antoine, Kubiak Aubin & Lermytte Lucan (2020) Migrants Produced by the Pôle 3D School, France Recommended by Wendy King |

Migrants is an animated film, beautifully crafted by five students at the Pôle 3D School in France. It has been highly praised with over 300 nominations and awards as official selections at film festivals, including wins for Best Animation Short (Saturnia Film Festival, 2022), Save the Earth Competition (Short Shorts Film Festival, 2021) and a BAFTA (Student Film Award for Animation, 2021). The film depicts the story of a mother polar bear and her cub who are forced to leave their pale blue Arctic home due to climate change and arrive as refugees in a very colourful land populated by brown teddy bears who do not welcome them, and eventually force them to leave. The narrative has a strong emotional appeal and would be well suited to students learning English from school grade 5 upwards. I have also used this film successfully while working on multimodal texts with student teachers undertaking university teacher education programmes.

The themes in Migrants can be used to explore numerous challenging topics in English language education, including the impact of climate change, the treatment of refugees and other vulnerable groups, coping with limited resources, family relationships and divergent approaches to unfamiliar situations. Some children or adolescents in the English language classroom may be refugees or migrants themselves and so this text provides a potential opportunity for students to connect to the story of polar bears and/or possibly to that of the brown teddy bears. Regarding the creative style, the film ends by juxtaposing animation with real-life footage, and the visual of a knitted polar bear toy washed up on the shore is especially evocative. Adolescent learners may make intertextual connections between this powerful imagery and photographs in news articles about Aylan Kurdi’s death, the two-year-old Syrian boy of Kurdish ethnicity who tragically drowned as his family tried to reach safety (Smith, 2015).

The Ridl framework (ELLiL Project Partners, 2023) referred to in the Introduction, highlights the importance of selecting texts based on their potential to engage learners on cognitive, affective, and social levels. Migrants has multiple affordances for deep engagement and provides teachers with several opportunities to extend learners’ topic-related lexis (such as migrant, immigrant, migration, refugees, global warming, to melt, glaciers, alienation, xenophobia, nationalism, protectionism). To foster the personal dimension of the framework, students might participate in a think-pair-share activity about their own experiences of feeling excluded or not welcome as a newcomer in different situations. Questions a class might then discuss include: How did being excluded make you feel? Why might school students sometimes reject newcomers? This discussion can lead into an initial viewing of the film, whereby the students complete a graphic organiser to identify the characters, settings, and plot. A more challenging viewing task could be for students to adopt the role of ‘symbols detectives’ and after the first viewing, they can work in pairs to share thoughtful feelings (Ratner, 2000) about the narrative’s many symbols.

To help develop secondary learners’ deep viewing competences, signpost tasks suggested by Kylene Beers and Robert Probst (2012) such as ‘contrasts and contradictions’ would be valuable for the second and third viewings. Students could work collaboratively to note the contrasts and contradictions that they see and hear, which focuses them on textual aspects such as colour and music, the two different habitats, the numerous differences between the bears including attitudes of the younger and the older ones, and importantly, the contrasting style of the film’s ending with the rest of the narrative. Students should be encouraged to interpret the significance of the contrasts, emphasizing that there are no ‘correct’ answers as they contemplate their ideas. They could discuss questions such as: Why do the polar bears walk on four legs and the brown bears on two? Why are the cubs more curious and less afraid than the adult bears? Why do the brown bears refuse to share their food? Why is the end of the film real and the rest animated? Are the actions of the brown bears fair (why or why not)? Next, groups of students could complete T-chart posters with these two columns: ‘Contrasts we noticed’ and ‘What we think this might mean’. Finally, they can share their posters as a gallery walk to notice further contrasts among different groups’ interpretations.

A particular affordance of a well-selected animated film such as this one, is that it can function as an accessible vehicle to explore a challenging topic such as the plight of climate refugees. Nevertheless, while the film’s characters are clearly fictional, a key goal of in-depth learning should be to connect the text’s themes to the real-world (Bland, 2023). Therefore, to enable students to move toward transformative action, they could plan concrete ways to support refugees in their school community and/or town. In my teaching context in Quebec, for example, we could knit hats for students who have arrived from warmer climates as dealing with harsh winters can be very difficult, so this is a hands-on way for students to welcome new classmates. Another idea is to invite guest speakers to the English classroom to share their various migration experiences, and by brainstorming a range of sensitive questions before each visit, students can raise their awareness of how migration experiences are varied – beyond the single story of the fictional bears.

An extension task could involve students carrying out some research online to find out more about the causes of the bears’ migration and share their ideas on ways to prevent global warming. Action-taking prompts might include: 1. What can we do as a school to help reduce global warming? 2. What can families do at home? 3. What actions can our local community take? In addition, there are also a range of creative ideas in Kieran Donaghy’s (2022) Film English lesson plan based on Migrants which would be worthwhile trialling and adapting with different school grades. With student teachers, the film could also function as a springboard text to consider the complex issues facing migrant workers and refugees and the impact of government policies, which might ultimately prompt kinds of action-taking which are both political and practical.

References

Beers, K. & Probst, R. E. (2012). Notice and note: Strategies for close reading. Heinemann.

Bland, J. (2023). Deep reading for in-depth learning. In M. M. Echevarría (Ed.), Rehumanizing the languages and literatures curriculum (pp. 81–99). Peter Lang.

Donaghy, K. (2022, January 24). ‘Migrants’ lesson plan. Film English. https://film-english.com/2022/01/24/migrants-lesson-plan/

ELLiL Project Partners (2023). Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework. https://site.nord.no/ellil/reading-for-in-depth-learning/

Ratner, C. (2000). A cultural-psychological analysis of emotions. Culture & Psychology, 6 (1), 5–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X0061001

Smith, H. (2015, September 2). Shocking images of drowned Syrian boy show tragic plight of refugees. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/shocking-image-of-drowned-syrian-boy-shows-tragic-plight-of-refugees

Wendy King is a lecturer in English teacher education at Bishop’s University in Quebec, Canada. She worked as a high school English teacher for 30 years and as the Language Arts Consultant for a local school board for a decade. Throughout this period and in her ongoing university work, Wendy has championed the teaching of deep reading and creative responses to multimodal texts.

|

Daunt, Sam (2017-ongoing) Once Upon a Picture https://www.onceuponapicture.co.uk Curated Images Website Trailer Recommended by Heidi Haavan Grosch and David Valente |

As the International Telecommunication Union (2020) highlights, ‘The internet has transformed how we live. It is entirely integrated into the lives of children and young people, making it impossible to consider the digital and physical worlds separately’ (p. ii). English language educators in school settings therefore have an important responsibility to foster critical visual literacy through the selection of teaching materials which integrate the digital world in an intentional and responsible way. Learners need regular opportunities during their lessons including in English classes, to focus deeply on images, to contemplate potential meanings thoughtfully and to develop a critical stance. To enable students to engage deeply with images in English, we should also equip them with relevant language to share their diverse interpretations.

Sam Daunt’s curated images website, Once Upon a Picture is valuable in contributing to these goals as it provides a free-to-access resource comprised of over 500 high quality artistic images, including many by renowned picturebook illustrators such as Quentin Blake, Shaun Tan, and Anthony Browne. The images featured on this site have been included with permission of the artists and this resource was born out of Daunt’s teaching experiences when using pictures with children to tell stories and help develop their visual literacy. Daunt shares some rationales for the pedagogical use of images in the ‘More’ section of the website, explaining that images ‘are immediate; they stimulate the imagination and promote creativity … children who often sit back are able and willing to contribute.’ The resource is a treasure trove especially when working with English learners in grades 5 – 7 who are transitioning from upper elementary to lower secondary school. Accompanying the site is a freely downloadable reading guide with sample pedagogical activities and links to useful resources.

The image banks from Once Upon a Picture can be used by English language teachers as individual visual prompts, almost like ‘sophisticated’ flashcards, or as curated collections arranged according to fictional characters, non-fiction events and themes which encourage in-depth learning. The structure of each collection follows a similar pattern, providing teachers with suggested questions for each image. These questions encourage English learners-as-viewers to examine the images closely, engage in discussions using meaningful lexis, and apply visual literacy skills. The questions can also function as prompts for learners’ collaborative creative writing.

Taking the Character collection as an example, there are 19 full-colour images such as The Jar Wizard, illustrated by Sean Andrew Murray; this sour-looking armoured knight is covered in glass jars filled with colourful, unnamed substances. Speculative questions such as ‘Who is he?’ and ‘Why is he carrying all those jars?’ provide an opportunity for learners to interpret and suggest possible stories behind the images. Matt Dixon’s Cliff seemingly depicts a rugged rock, or is it a monster? This is for each group of learners to decide and questions like these open the classroom space for discussions about images from multiple perspectives. An elderly woman gazes into the pages of a book, her younger self reflected in Jungho Lee’s Fall, and here, the questions prompt learners to collaboratively write stories about the woman’s life – offering some excellent practice of narrative tenses. At the beginning of this collection, ‘20 questions to get to know a character’ are suggested accompanied by a useful pre-viewing lead-in activity for learners before they start to look at the images. Throughout this process of exploring these visual stories, learners can also raise their awareness of varied literary conventions.

The questions that accompany each image offer additional springboards for productive language tasks. They can scaffold fiction and non-fiction creative writing and/or act as contexts for building spoken dialogues. For example, learners can interview the character in an image, create a news report about the setting, or imagine themselves as a particular character and write a monologue as a kind of internal dialogue or an ‘I am…’ poem expressed from the character’s point of view. The questions are easily differentiated as learners with less proficiency in English can use fewer or simpler words when describing the images and those with more advanced speaking and writing skills can incorporate metaphors and similes. During our university teacher education courses, we encourage our student teachers to select an image and explain to the group which school grade they might use it with as well as the learning purposes. This sharing includes both target linguistic aims and wider educational goals.

The images and prompts on this website offer concrete tools for class work with language as learners-as-viewers are inspired to respond to what they see, using their own words, through dialogue, narration, or reflection. Talking about what they see and explaining why they have interpreted an image in a particular way, provides learners with valuable linguistic stretching as well as training for critical thought for encounters with images, especially those on social media and the world outside school. In our experience, regularly discussing the lenses through which we view images can help create an environment of compassionate interaction and foster students’ willingness to take risks in the ELT classroom. Once Upon a Picture is also on Facebook (http://www.facebook.com/onceuponapicture) and Twitter (http://twitter.com/ouapicture).

Reference

International Telecommunication Union. (2020). Guidelines for parents and educators on child online protection. ITU Publications. Available: https://www.itu-cop-guidelines.com/_files/ugd/24bbaa_4d94c1654ee44aae8976bb39645fced9.pdf

Heidi Haavan Grosch is an assistant professor of English teacher education at Nord University in Levanger, Norway. As she wanders through storyworlds with children in an elf forest on a Christmas tree farm, or with (student) teachers in the university or school classroom, she uses images extensively. Heidi’s YouTube channel CyberBridge helps inspire teachers of English to engage with story including reading images, words and the imaginative spaces in-between.

David Valente is a PhD research fellow at Nord University, Norway where he specializes in English teacher education for grades 1–10. He is the reviews editor for Children’s Literature in English Language Education and the Communications Director for the Early Language Learning Research Association (ELLRA). His research interests are children’s literature, interculturality and in-service teacher education.