| Multimodal Texts to Facilitate In-Depth English Learning

Introduced by Alyssa Magee Lowery |

Download PDF |

This year’s convergence of passionate and knowledgeable researchers in the field of literature for English language education in Bodø, Norway, not only brought opportunities for dissemination of exciting research, but for encounters with excellent works of literature recommended by experts from around the world. In the Reading for in-depth English Learning (RidEL) conference, session after session, panel after panel, and keynote after keynote came with introductions to a variety of texts that could facilitate in-depth English language learning as well as engagement with interculturality, diversity, and critical literacy.

The texts recommended in this issue span genre and format, spotlighting the role of multiple literacies in the English language classroom. In Compelling Stories for English Language Learners: Creativity, Interculturality and Critical Literacy (2022), Janice Bland highlights the largely multimodal nature of contemporary engagements with English, noting,

While literary narratives in the written word have long coexisted with the older modalities of oral and pictorial storytelling, the combinations of linguistic, visual, aural, spatial and gestural semiotic modes in global communications via the internet means that students’ literacy practices are now principally multimodal (p. 18).

Reading for in-depth learning, then, must be understood to include literary literacy as well as many additional types of reading skills. Bland highlights functional, visual, information, media, and critical literacies in addition to literary literacy (pp. 18–22), all of which contribute to deep reading and communion between reader and text.

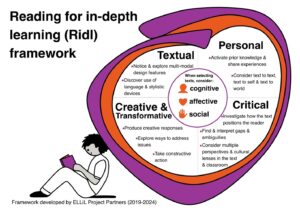

The Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework (2023) on which this year’s conference was based places textual, personal, critical, and creative and transformative dimensions as central sites of deep cognitive, affective, and social engagement with texts.

Figure 1: The Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework

The texts recommended in this issue employ a broad definition of ‘Reads’, though the ‘Recommended’ component is as hearty as ever. All four invite teachers and learners in English language classrooms to deeply explore multiple modes of textuality, to connect personally with narrative, to critically consider content and positionality, and to respond creatively to engaging stories.

The Magic Fish, a graphic novel presented by Colin Haines, harnesses the dual modes of visual and linguistic to tell a compelling and affirming story about the power of narrative across generations and homelands. Daniel Finds a Poem, a traditional picturebook recommended by Heidi Haaven Grosch, evokes the concept of poetry, facilitating visual literacy and literary literacy while challenging readers to consider the poems we might all find in our daily lives. Hike, a wordless picturebook introduced by Alyssa Magee Lowery, invites readers to co-construct a visual narrative, perhaps experimenting with their own linguistic resources to make meaning. Finally Wish, a popular animated film introduced by Jade Dillon Craig, combines literary, visual, aural and critical literacies as it engages with concepts of power, agency, and political action. Though they differ in form, all four contributions constitute excellent starting points for the facilitation of in-depth reading.

References

Bland, J. (2022). Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy. Bloomsbury.

ELLiL Project Partners (2023). Reading for in-depth learning (Ridl) framework. English Language and Literature – In-Depth Learning. https://site.nord.no/ellil/reading-for-in-depth-learning/

Nguyen, Trung Le (2020)

The Magic Fish

New York: Random House Graphic

Recommended by Colin Haines

Trung Le Nguyen’s debut graphic novel, The Magic Fish is a semi-autobiographical account of coming out. In it, Tiến, the son of Vietnamese refugees to the United States, wants to tell his parents that he is gay. The only problem is he doesn’t know how. As he puts it, he doesn’t ‘know the Vietnamese words for it’ (p. 172).

Central to The Magic Fish are issues of language, tradition, and identity – and how all three intersect. Tiến and his mother communicate in both Vietnamese and English, though their communication lacks, in his mother’s words, balance: she speaks mostly Vietnamese, her son speaks mostly English (p. 3). Nevertheless, they communicate largely through the fairy tales they tell each other, a tradition they have carried on since Tiến was a child. Fairy tales provide not only language practice for both mother and son, but stories and characters that are easily recognized across cultures. The Magic Fish includes two versions of the Cinderella story, for example, the German ‘Allerleirauh’ and the Vietnamese ‘Tâm Cám’. Also included is ‘The Little Mermaid’, albeit in modified form. As Tiến’s mother notes, fairy tales ‘can change, almost like costumes’. Nevertheless, as she also points out, ‘I imagine the script stays the same, but the context always shifts’ (p. 5). Ultimately, she proves herself wrong as she changes not just the context, but the script itself in the novel’s final tale. Whereas most traditional fairy tales encode heterosexual romance, Tiến’s mother changes the script to include a gay ending. In this way, she is able to communicate to her son her acceptance of his sexuality.

As Barbara Tannert-Smith (2023, p. 22) has noted, The Magic Fish is structurally complex. Not solely a matter of the way in which fairy tales are interspersed into what is otherwise a coming out story, the narrative also interjects the past into the present; Tiến’s mother is continually beset by memories of Vietnam and the family she left behind. Ultimately, she returns to that country, briefly, when her mother dies. To differentiate between these stories, however, is fairly straightforward. The colour palette changes depending on each: red (and shades of red) represent the present; gold, the past; and blue represents a fairy tale being read or retold by mother or son. As the canny reader will soon discover, connections across stories abound. The aunt in ‘Allerleirauh’ saves the day, just as Tiến’s mother’s aunt gives her niece advice and a new way of thinking upon her return to Vietnam. Tiến’s parents’ Catholic faith provides inspiration and succour when they flee Vietnam, though the Church acts differently when addressing Tiến’s sexuality.

Due to its complexity and, at times, adult themes, The Magic Fish is perhaps best suited to adolescents and/or young adults, ages thirteen and up. Nor is it limited to this audience; as Tannert-Smith (2023, pp. 22-23) points out, it also functions well for more adult readers of English.

Bibliography

Nguyen, T. L. (2020). The Magic Fish. Random House Graphic.

References

Tannert-Smith, B. (2023). ‘And now this story is ours’: Fairy tale and collage in Trung Le Nguyen’s The Magic Fish. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 61(1), 22−29.

| Colin Haines is Associate Professor of English at Oslo Metropolitan University, where he teaches children’s and young adult literature to pre- and in-service teachers of English. He is the author of “Frightened by a Word”: Shirley Jackson and Lesbian Gothic (Uppsala Universitet, 2007), as well as articles on children’s and young adult literature. |

Archer, Micha (2016)

Daniel Finds a Poem

London: Nancy Paulsen Books

Recommended by Heidi Haavan Grosch

Daniel Finds a Poem by Micha Archer embraces the dance between image and text. Beautifully illustrated with the author/illustrator’s signature collage, this picturebook takes us through a week in a park with young Daniel who asks, ‘what’s poetry?’ (Archer, 2016). His daily encounters with the animals and insects he finds there, open his eyes to seeing in a new way. For example, Spider says, ‘to me poetry is when morning dew glistens’, evoking an awareness that dew drops gather in the early morning to quench the thirst of a spider as well as outline the intricacies of the spider’s web. The descriptive language in the simple text utilizes poetic devices such as alliteration (‘in the shade of the slide’), onomatopoeia (‘crisp leaves crunch’) and the use of the senses (‘sun-warmed sand’). Archer writes in ‘Discovering the concept of poetry with Daniel Finds a Poem’ that she thinks of poetry as ‘a painting moment with words’ (Archer, 2024b) and believes it can be found everywhere. This is certainly true for Daniel who ends his week gazing out on a sunset-painted pond: ‘That looks like poetry to me’ (Archer, 2016).

Daniel Finds a Poem lends itself well to both listening to and writing poetry, inspiring action and participation and perhaps empowering a closer relationship to the natural world. Younger learners can take on the persona of the creatures they meet in the pages or learn the days of the week. Older learners can use these short poems as model texts, writing poems of their own inspired by the animals and insects they encounter in nature.

Archer’s use of colour and pattern is influenced by the folk art, crafts, and architecture of the countries she has visited and lived in, and as a former kindergarten teacher herself, she often works with educators on how to incorporate art into their own classrooms. Working in oil, watercolours, pen and ink, and collage, both digitally and on paper, her illustrations echo the style of Ezra Jack Keats, known for works such as The Snowy Day (Keats, 1962). In 2017 Daniel Finds a Poem won the Ezra Jack Keats award, and in her 2017 acceptance speech, Archer credited her decision to set Daniel Finds a Poem in a city park to Keats, ‘who made books in which children who live in cities could feel seen and celebrated’ (Archer, 2017). She also credits her early work in collage compositions to him. The illustrations in this picturebook can easily inspire all ages of children to create their own. They could, like Archer, create homemade stamps to then use to paint the paper for the final collage. I recommend watching Archer’s video on her process (2015), ‘How does she do that?’

Daniel Finds a Poem is the first book Micha Archer both wrote and illustrated, and since its publication her repertoire has grown to include two new books about Daniel: Daniel’s Good Day (Archer, 2019) and What’s New Daniel (Archer, 2024a). I encourage English language teachers to explore her work, using both the words and pictures to open doors to discovery, imagination and connection with the natural world for themselves as well as the children they work with.

Bibliography

Archer, M. (2016). Daniel Finds a Poem. Nancy Paulsen Books.

Archer, M. (2019). Daniel’s Good Day. Nancy Paulsen.

Archer, M. (2024a). What’s New Daniel. Nancy Paulsen Books.

Keats, E. (1962). The Snowy Day. Viking.

References

Archer, M. (2015). How does she do that? [Video]. Micha Archer’s Homepage. http://www.michaarcher.com

Archer, M. (2017, February 23). Press Release: 2017 Ezra Jack Keats Book Award winners announced. Ezra Jack Keats Foundation. http:// www.ejkf.org/2017/02/press-release-2017-ezra-jack-keats-book-award

Archer, M. (2017, March 29). Micha Archer reads Daniel Finds a Poem. Nathaniel Rasmussen YouTube Channel. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZC80z2geqk

Archer, M. (2024b). Discovering the concept of poetry with Daniel Finds a Poem. Brightly. http://www.readbrightly.com/discovering-concept-poetry-daniel-finds-poem/

| Heidi Haavan Grosch is Assistant Professor in the teacher education program at Nord University, Norway and has spent most of her career working with children. She constantly finds inspiration from the world around her which inspires her teaching, learning, writing and art which she shares every Monday: http:// www.youtube.com/@HeidiMondayMusings. |

Buck, Chris & Veerasunthorn, Fawn (2023)

Wish

Walt Disney Animation Studios

Recommended by Jade Dillon Craig[1]

Acting as a closing bookend to Disney’s first 100 years of animated features, Wish (2023) tells the story of Asha, a heroic citizen of Rosas, a nation founded on the power of wish fulfillment by a magician named Magnifico. Immigrants flock to Rosas to have a chance to see their heart’s desires granted, and they entrust their deepest wishes to Magnifico’s care on their eighteenth birthdays, forgetting them entirely unless they are lucky enough to be chosen as a rare grantee. When Asha discovers that Magnifico is hoarding wishes with no intention of granting any that he perceives as any potential threat to his power, she undertakes a quest to restore the wishes of Rosas’ people and grant them the agency to pursue their own dreams and goals without the intervention of a tyrant.

Studies on multiliteracies and the evolution of new media suggest that ‘we should combine language-based theory with semiotics and other visual theories if we are to give an adequate and contemporary meaning to the term “literacy” in the 21st century’ (Donaghy, 2019, p. 4). Among the many advantages in general to the use of film in the EFL/EAL classroom are the opportunity to foster critical thinking, broaden pupils’ literacy skills in English, and engage in comprehensive discussions that increase language output. Furthermore, as Kieran Donaghy (2019) notes, ‘using films from the target language culture in the language classroom is a powerful way to help language students understand different cultures and intercultural relationships’ (p. 8).

As a feature film from a popular studio, Wish has the potential to reframe language learning in the contemporary EFL/EAL classroom through increased motivation and language immersion, fostering language acquisition through authentic texts and encouraging cultural understanding (Hameed, 2016; King, 2002). It affords pupils the opportunity to develop their visual literacy skills and critical media literacy abilities through in-depth learning and engagement with multimodality. ‘Reading’ film allows pupils to express their own imaginative understanding of the text and creates room for both language input and output. Whether implicitly or explicitly, film harnesses critical thinking and the ability to express those thoughts in the target language.

Wish (2023) is a rich source text for the EFL/EAL classroom, engaging with politics and civics, and requiring critical engagement with the concept of power, aiding in development of pupils’ critical thinking. The film supports visual, critical, and media literacies which develops multiliteracy skills. Lastly, Wish features contextualized dialogue and exaggerated animated body language and facial expressions which harnesses language skills. Wish might reasonably be used in the upper primary or lower secondary years with activities adjusted to students’ levels of comprehension. The themes of self-determination and civic responsibility can be approached at a range of levels, and the engaging musical components and comedic elements can entertain viewers of any age. To use Wish to approach visual and narrative literacy, teachers might isolate particular frames or scenes for close reading. In this film in particular, two ideas are (1) to compare the mise-en-scène in Magnifico’s dungeon workroom to the one belonging to the Wicked Queen in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, considering the semiotics of power and evil, or (2) to analyze the scene in which Simon’s wish is granted and revealed to uncover how viewers are meant to understand it as a dangerous turn of events. Teachers of older students might also use the film interdisciplinarily to introduce concepts of civil disobedience and justice, pairing the film with focal questions related to the responsibilities and rights of governments and the governed. Wish stands to offer an engaging and rich literary encounter for teachers and students alike.

Bibliography

Buck, C., & Veerasunthorn, F. (Directors). (2023). Wish [Film]. Walt Disney Animation Studios.

References

Donaghy, K. (2019). Using film to teach languages in a world of screens. In C. Herrero, & I. Vanderschelden (Eds.), Using film and media in the language classroom: Reflections on research-led teaching (pp. 3−16). Multilingual Matters.

Hameed, P. F. M. (2016). Short films in the EFL classroom: Creating resources for teachers and learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 5(2), 215−219. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.5n.2p.215

King, J. (2002). Using DVD feature films in the EFL classroom. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 15(5), 509−523. https://doi.org/10.1076/call.15.5.509.13468

| Jade Dillon Craig is Associate Professor of Children’s Literature at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway. She is the author of From How to Catch a Star to Now: Theorising Oliver Jeffers’ Picturebooks (under contract with Routledge) and co-editor of Family in Children’s and Young Adult Literature (Routledge, 2023). She has published several book chapters and articles related to children’s literature, Alice studies, fairy tales, and visual texts for young readers. |

Oswald, Pete (2020)

Hike

London: Walker Books

Recommended by Alyssa Magee Lowery

Pete Oswald’s Hike is a wordless picturebook rich with detail, compelling in narrative, and well-suited to English language learners in the lower and upper primary years. It follows a parent and child on a much-anticipated hike, inviting readers to co-construct narrative as the family plans and packs, travels from the city to the forest, takes on several challenges, enjoys one another’s company, participates in a family tradition, and returns home to reflect on the journey. Noting his own childhood experiences hiking through the wilderness with family, Oswald grounds his reasoning for the book’s wordlessness in its potential for the kind of personal engagement that feeds in-depth reading. Speaking with Let’s Talk Picturebooks (Schuit, 2020), he explains, ‘Ever since I was young, I’ve always loved wordless picturebooks because I could put my own spin on the story. I like it when books leave room for the reader. Empowering the reader to make the story personal seemed appropriate for this book’.

Oswald offers the example of the design of the child character as a site for personal interpretation. ‘Ultimately, my goal was to make a universal story that everyone can relate to. So I tried to make the child more gender neutral. Since this is a wordless book I didn’t have to say “he” or “she”’ (Schuit, 2020). In this regard, as in many others, the wordless nature of the book indeed ‘leaves room for the reader’, as Oswald says, and invites the reader to become part of the meaning-making process. Readers of Hike are presented with opportunities to read deeply, engaging in the co-construction of narrative that Evelyn Arizpe (2014) emphasizes as a form of ‘active participation’ (p. 96). In her list of ‘the main demands that wordless picturebooks make of readers’, she includes, ‘Readers must find and re-create the story by searching for clues, bits of information, and any details that provide continuity and elaborate a hypothesis about the different connections between pictures’ (p. 96). For Hike, this is especially fulfilled through a strand of the narrative that sees parent and child planting a conifer at the top of the mountain and photographing themselves with it, later placing the picture in an album alongside similar photos that appear to be from several successive generations who completed the same hike with the same goal.

Wordless picturebooks have immense potential for facilitating in-depth reading, requiring readers to engage at the textual level through deep reading of ‘facial expressions, gestures, setting, events, actions, and motives…inferred from the sequence of images’ (Serafini, 2014, p. 25). In sequences like the one in Hike featuring the parent-child duo crossing a fallen tree over a stream, readers must exercise these visual literacy skills, pairing that information with their own personal experiences to understand the feelings of the main characters. They also support critical reading, requiring readers to support their interpretations of the narrative in a case where meaning is ambiguous and even unfixed (Louie & Sierschynski, 2015). The Visual Thinking Strategy described in this issue by Shaun Nolan is an equally compelling strategy for interpretation of a wordless narrative for English language learning as readers draw on their available language resources to read the language of image and express their findings in English.

Hike is a fantastic first text for any English language teacher interested in introducing wordless picturebooks to readers. While it provides opportunities for interpretation, it remains grounded in experiences that may be familiar or relatable to many readers who may already possess some of the relevant English vocabulary to describe or analyze its illustrations. An expanded library might benefit from even more abstract or mysterious texts, but Hike is a splendid place to begin.

Bibliography

Oswald, P. (2020). Hike. Walker Books.

References

Arizpe, E. (2014). Wordless picturebooks: Critical and educational perspectives on meaning-making. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), Picturebooks: Representation and narration (pp. 91–106). Routledge.

Louie, B., & Sierschynski, J. (2015). Enhancing English learners’ language development using wordless picture books. The Reading Teacher, 69(1), 103−111.

Schuit, M. (2020, February 13). Let’s Talk Illustrators #131: Pete Oswald. Let’s Talk Picture Books. https://www.letstalkpicturebooks.com/2020/02/lets-talk-illustrators-130-pete-oswald.html

Serafini, F. (2014). Exploring wordless picture books. The Reading Teacher, 68, 24−26.

| Dr Alyssa Magee Lowery is Associate Professor of Children’s Literature and Young Learners at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). Her chief research interests are children’s literature and media in use, cultural studies and the study of popular culture for children and families, and the teaching of English as an additional language through authentic children’s media. She is the project leader of eBLINK.no, a resource for Norwegian teachers of primary school Englishand has recent publications in Bookbird. |

[1] The conference presentation on which this contribution is based was given with Alyssa Magee Lowery at RidEL.