| Recommended Reads | Download PDF |

John Burningham

27 April 1936 – 4 January 2019

It was with much sadness that we heard the news of John Burningham’s death in early January this year. He was a highly regarded picturebook illustrator who contributed enormously to the evolution of picturebook making as we know it today. It is for this reason we decided to dedicate this issue of Recommended Reads to his picturebooks.

Maurice Sendak, Burningham’s contemporary, described his work as ‘stunning, luscious, sexy, hilarious and mysterious and frequently just plain nuts’ (2009, p. 7). Together, in the early ‘60s and from their different continents, they took the world by storm, benefiting from what has been called a post-war ‘graphic explosion … a new world of children’s books’ (p. 8). Burningham’s first book, Borka (1963), came at a time when publishers were willing to take risks with an expanding book market and possibilities for new approaches to colour lithography allowing artists to replicate their distinctive painterly styles (Alderson, 2009, p. 9). But Burningham was not just an incredible artist, he was skilled at ‘wedding’ image and word to enhance the ‘startling, comic [even] absurd adventures’ found in his picturebook narratives (Alderson, 2009, p. 10). In an interview for the Magic Pencil Exhibition he said: ‘I feel that above all my audience is not just children, it’s much broader than that, it’s people. And whilst I’m working towards simplification, I’m trying to steer away from childish things’ (Blake & Rose, 2002, p. 62).

Burningham’s books combine words and pictures to reflect the worlds of both childhood and adulthood; he does not speak, write or paint down to children, but treats them with respect. In his autobiography, he writes:

There is a misconception that picture books for children should be packed with colour and decoration on every page. This is rather like saying a successful piece of music should be crammed full of loud notes. It’s the juxtaposition and build-up of sound that make music interesting. (Burningham, 2009, p. 127).

His picturebooks may not be a natural choice in the English language classroom, but the four recommendations here make suggestions for their inclusion. They come from [end of page 87]

colleagues who have founded the ‘Picturebooks in European Primary English Language Teaching’ (PEPELT) project, which can be followed on social media.

References

Alderson, B. (2009). John Burningham’s Children’s Books. In J. Burningham, John Burningham. London: Random House Books.

Blake, Q. & Rose, A. (Eds.) (2002). Magic Pencil: Children’s Book Illustration Today. 2002. London: The British Council/The British Library.

Burningham, J. (2009). John Burningham. London: Random House Books.

Picturebooks in European Primary English Language Teaching (PEPELT). https://www.facebook.com/PEPELT21/

Sendak, M. (2009). Foreword. In J. Burningham, John Burningham. London: Random House Books.

Burningham, John (1973). Mr Gumpy’s Motor Car.

London: Puffin Books.

Recommended by Gail Ellis

In this sequel to Mr Gumpy’s Outing (1970), Mr Gumpy sets off for a ride in his motor car, but it is not long before some children and a number of animals ask if they can come along too. ‘All right,’ said Mr Gumpy. ‘But it will be a squash’. As it’s a nice day, Mr Gumpy decides to drive across the fields, but the sky clouds over, the rain comes down, and the car gets stuck in the mud. ‘Some of you will have to get out and push’ says Mr Gumpy, but nobody wanted to and there was excuse after excuse echoing those in The little Red Hen. ‘Not me’, said the goat. ‘I’m too old’. ‘Not me’, said the calf. ‘I’m too young’, etc. But in the end, they all had to get out [end of page 88] to help, ‘They pushed and shoved and heaved and strained and gasped and slipped and slithered and squelched’.

What delightful child-friendly language typical of that found in children’s picturebooks! I checked if any of these onomatopoeic, alliterative words featured in the combined vocabulary lists of the Cambridge Assessment Young Learner tests, Movers, Starters and Flyers. Only push appears. So we can see that picturebooks expose children to rich authentic language in meaningful contexts anchored in the child’s world. Once the car is out of the mud, the sun starts to shine, and they go for a swim. ‘Goodbye’, said Mr Gumpy. ‘Come for a drive another day’. The story carries a strong message about teamwork, sharing and helping others.

The layout of the pages places the verbal text on the verso page with the colour illustrations generally on the opposite recto page. There are a few double spreads where the illustrations cross the pages to convey a sense of movement as the drive progresses. The illustrations are in John Burningham’s familiar style of ink line drawing and delicate pastel colours and synchronize with the words to support primary-aged children in understanding the story. It’s a picturebook which fits nicely into any topic sequence related to farm animals or the weather. The story has a clear sequence of events with plenty of dialogue in the form of short phrases, so it lends itself well to being acted out. Story notes are available in the first edition of The Storytelling Handbook (Ellis & Brewster, 1991).

References

Ellis, G. & Brewster, J. (1991). The Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. 1st ed. Penguin Books Ltd.

Gail Ellis has over 30 years’ experience as a teacher, teacher educator and manager. Her recent publications include Tell it Again! and Teaching Children How to Learn. Her main interests are picturebooks in ELT, young learner ELT management, inclusive practices and children’s rights. Gail is co-founder of the PEPELT project. [end of page 89]

Burningham, John (2003). The Magic Bed.

London: Penguin Random House.

Recommended by Anneta Sadowska

The Magic Bed is a beautifully illustrated story by John Burningham. Georgie is a lonely child who lives with his grandmother and two adults – Frank and a nameless woman. We don’t know if they are his parents, but we can clearly see that it is the granny who runs the household. When Georgie outgrows his baby bed, Frank takes him to an antique shop, and they buy a new bed. They are told by the shop assistant that it is a magical bed, and they find an inscription on the headboard saying that the magic word will make the bed fly. We, the readers, are never told the magic word, but we are encouraged to find our own magic words.

Georgie discovers the magic word which allows him to fly to different places, where he goes on many adventures. This is where the illustrations become colourful and warm. Georgie becomes the centre of attention. The night-time expeditions bring much-needed colour into his life, which is reflected in the artwork. The story ends dramatically when his granny throws away his magic bed, to replace it with an ordinary one, but fortunately Georgie’s adventures had given him the courage to go to the dump, retrieve his bed and soar off into the unknown, celebrating the power of imagination.

The Magic Bed is a perfect book for cross-curricular and integrated English language education. It can be used for literacy development, children can brainstorm their own magic words and even magic spells. They can work with a map in geography and talk about the time zones and distance they would need to travel to get to the destinations they would like to reach. While doing science they could describe the varying biomes and habitats. Art and design lessons can provide an opportunity to explore different materials prompted by the illustrations which include mixed-media. Finally, children could design their own magic bed as a pre-reading or post-reading activity which would provide ample opportunities for speaking activities and practicing presentation skills. [end of page 90]

Anneta Sadowska-Martyka is a psychologist, teacher trainer and a primary English teacher in Warsaw, working with children aged 6–12. In 2008, she was awarded The European Language Label for her programme ‘Sharing Stories about Cooperation’ based around picturebooks. Anneta is currently working on developing a course for teenagers, using picturebooks to foster social and emotional intelligence. Anneta is co-founder of the PEPELT project.

Burningham, John (1996). Courtney.

London: Red Fox

Recommended by Tatia Gruenbaum

Courtney is the story of two children who beg their parents for a dog. Finally, the parents give in, but instead of following their parents’ advice to select a pedigree dog, the children choose Courtney, a dog from the local dog shelter. Upon their return home, Courtney receives a rather frosty reception from the parents as they do not consider her a ‘proper dog’. By the next morning Courtney has disappeared, only to return a few hours later with a large trunk. From that moment on, life changes for both the parents and the children, as Courtney clearly is no ordinary dog. She can cook, play the violin, juggle, clean the house and when fire breaks out, it is Courtney who rescues the baby from the flames. Then one day Courtney is gone and so is the trunk. After weeks of searching, the family finally gets used to life without Courtney again. However, one summer holiday when the children get into trouble out on the open sea in their small rubber boat, they are miraculously pushed ashore. Perhaps, in the end, Courtney never was far away. [end of page 91]

As so often happens, I came across this picturebook by chance. The rather unusual almost square format of this book and the large image of a dog pulling an old-fashioned trunk caught my attention. Throughout the book, the illustrations on each page continue to play this central role, a minimal setting focusing on depicting the characters and their activities. Burningham’s illustrations are large and detailed, and colour is used only to accentuate; the white background adds lightness to the page. The verbal text is concise, and the font is unusually large, which makes it easy for shared read-alouds. Interestingly enough, page by page, the positioning of the text alternates from bottom to top, which adds an implicit rhythm to the act of reading.

The cover of a dog pulling a large trunk sets the scene for this mystery story. Throughout the book, the illustrations and story entice children to speculate and perhaps solve the mystery of who Courtney is, where Courtney has gone and if in the end Courtney rescued the children. Evidence can be found in the images, but a careful eye is required. There are some wonderful opportunities for including this in ELT. Apart from Courtney, no names have been given to any of the characters, so children can think about possible names and create short dialogues to act out the story. A mystery story like this needs a sequel, so children could create short ‘Courtney sequels’, combining creative thinking with language learning. There is also a deeper message: the dog nobody wanted turns out to be a protecting, life-long friend who nevertheless suddenly leaves. Perhaps this can stimulate discussion about unusual friendships, feelings of rejection and acceptance. Courtney might not be one of John Burningham’s best-known books, but it is certainly one worth considering for ELT with older primary children.

Tatia Gruenbaum is a Lecturer at the Avans University of Applied Sciences in Breda, the Netherlands, and a PhD student at University College London Institute of Education. Her research is centred on the use of picturebooks as a tool in primary teacher education in the Netherlands. Tatia Gruenbaum is also the founder of a successful not-for-profit English children’s book project called The Little English Library and co-founder of the PEPELT project. [end of page 92]

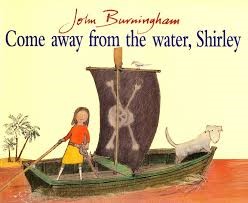

Burningham, John (1977). Come Away from the Water, Shirley.

London: Red Fox

Recommended by Sandie Mourão

Come Away from the Water, Shirley is about a trip to the seaside by Shirley and her parents. Interestingly, Burningham describes his book as ‘a commentary on the way one carries on as a parent’ (Burningham, 2009, p. 127) and successfully gets his message across by creating an ironic juxtaposition between the illustrations on facing pages. On the left-hand page, Shirley’s parents sit on deckchairs and have a rather boring day – knitting, reading the newspaper and snoozing. The illustrations are in Burningham’s sketchy style with coloured crayons and pastel colours. On the facing right-hand page, Shirley has the most amazing adventures with a stray dog – they row out to a pirate ship, are made to walk the plank, escape with a treasure map, find treasure and return to the beach with gold and silver. Here the illustrations are richer and more painterly in style, and fill the frame that surrounds them. The verbal text, which remains on the left page, contains the uninteresting remarks and warnings called out by Shirley’s mother: ‘Of course, it’s far too cold for swimming Shirley’ or ‘Don’t stroke that dog Shirley, you don’t know where he’s been’. By showing the illustrations on facing pages, the two stories are contrasted: ‘On one level the pictures are funny, but on another they demonstrate the tragic lack of communication between parents and their children’ (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 1999, p. 167).

This picturebook is rarely chosen for the ELT classroom, for the words do not match the images and teachers may be unsure how it might be shared. However, this is its very strength! The semantic gap between words and images allows for an active reader, one who will have to make sense of both modes to really enjoy the book. We can share this kind of picturebook with slightly older primary learners, who have a little more language, and encourage them to talk about the facing pages, ‘How are they different?’ Here children may [end of page 93] notice the different illustrative styles and colours, but also that each focuses on the different characters. ‘What do they think the author-illustrator is trying to do?’ – here they might talk about real, adult worlds and imaginary, child worlds. They may even share their own sea-side adventures – real or imaginary.

The front cover gives us a clue as to Shirley’s exciting day, as do the maps on the endpapers, which can be revisited and giggled over. The title page shows Shirley and the dog triumphantly holding up their pirate flag, with swords and pistols around their waists. These peritextual features can be used to support predictions, inference making and meaningful use of English. Children can think about where in the story the front cover and title page illustrations fit, or come up with possible dialogues between Shirley and the dog. They may even want to write Shirley’s story.

References

Burningham, J. (2009). John Burningham. London: Random House Books.

Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (1999). Metalinguistic awareness and the child’s developing concept of irony: the relationship between pictures and text in iconic picture books. The Lion and the Unicorn, 23(2), 157-183.

Sandie Mourão (PhD) is a researcher at Nova University Lisbon, where she is investigating children’s literature and intercultural citizenship in primary English education. She is co-editor of the CLELEjournal and co-founder of the PEPELT project. [end of page 94]