| Recommended Reads | Download PDF |

Literature Exploring Refugee Experiences

Introduced by David Valente

The inherent potential of children’s literary formats with characters’ voices that elicit empathetic responses from children and teenagers has received significant scholarly attention. This includes the affordances of such literature for what Bishop (1990) refers to as ‘windows’ on other worlds; however, as Johnson, Koss and Martinez (2018) maintain, there remains insufficient focus on ways that young readers can be supported in moving beyond windows to venture ‘through sliding glass doors’. Bland (2020) conceptualizes this specifically in relation to refugee literature as a strong emotional connection to the characters and events which leads to a meaningful shift in the reader’s perspective. She highlights how ‘a stirring literary portrayal of the refugee experience can provide a kind of magical mirror, drawing us into a different world where we encounter others with empathy’ (p. 69).

The recommended reads in this issue illuminate refugee experiences via four very different formats: a picturebook, a verse novel, a graphic novel and an information book. They can be meaningfully used in English language education, selected according to children’s and teenagers’ ages and language levels, as well as connected to particular curricular goals and themes. Furthermore, these books act as bridges of understanding between the characters’ worlds and the young readers’ own cultural identities, made accessible in the English language classroom by the rich variety of pedagogical devices outlined by the four contributors in this feature.

However, in order to enable readers to transcend intercultural comparison and go ‘through sliding glass doors’, learners of English should also be encouraged to reflect deeply on ideological questions regarding cultural appropriation and authenticity of experience. As the authors of the formats are not themselves refugees, Delanoy’s proposal of ‘text ensembles’ (2018, p. 152) can be used to alleviate the effects of a single story and potential cultural (mis)appropriation by ensuring genuine refugee voices and experiences are clearly audible alongside the books. Involving children and teenagers in compiling text ensembles by engaging in research online is empowering and has the potential to translate into impactful social justice actions. As Cory-Wright (2016) demonstrates, teenagers have used social media such as Instagram to argue for gender equality and YouTube to speak out against human trafficking, compelling evidence of a desire to participate, take a stand and go boldly ‘through sliding glass doors’.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Retrieved May 5, 2020 from https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf

Bland, J. (2020). Using literature for intercultural learning in English language education. In M. Dypedahl, & R. Lund. (Eds.), Teaching and Learning English Interculturally. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, pp. 69-89.

Cory-Wright, K. (2016). Intercultural competence in secondary English language education – 30 years of change. Children & Teenagers Pearl Anniversary Edition, IATEFL Young Learners and Teenagers Special Interest Group Publication. Faversham: IATEFL, pp. 50-53.

Retrieved May 5, 2020 from https://yltsig.iatefl.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/5464bcdd-9dc1-492e-ab83-6c7af1064498.pdf

Delanoy, W. (2018). Literature in language education: Challenges for theory building. In J. Bland. (Ed.), Using Literature in English Language Education. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 141-157.

Johnson, N.J., Koss, M.D., & Martinez, M. (2018). Through the Sliding Glass Door: #EmpowerTheReader. The Reading Teacher. 71(5), 569-577.

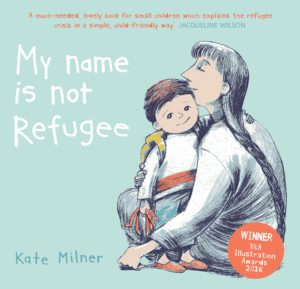

Milner, Kate (2017). My name is not Refugee.

Edinburgh: The Bucket List.

Recommended by Sónia Ferreirinha

Imagine that your town or city is no longer safe, and you are suddenly forced to leave. Ask yourself: What shall I take? How far will I need to walk? Can I speak a new language? What things would remind me of home? These are some of the thought-provoking questions children encounter in Kate Milner’s award-winning (Klaus Flugge Prize, 2018 and V&A Student Illustrator of the Year, 2016) picturebook, My name is not Refugee. The plot centres on a mother and child who leave their country due to the dangers of war and compassionately shares the mother’s explanations of what might happen on their journey. Milner’s use of this relatable parent-child dialogue and her powerful illustrations, successfully anchor the refugee crisis within the child’s world and, in turn, make it comprehensible and accessible for young readers.

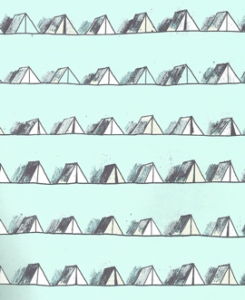

My name is not Refugee has several affordances for the English language classroom with children aged 9 to 12. The language and images clearly convey the meaning of new vocabulary and offer many opportunities for personalized questioning while reading aloud. It can also be used by English teachers for intercultural learning and the development of empathy with the refugee experience. Starting from children’s own familiar experiences and guiding them to gradually recognize the refugee experience, teachers can show the illustration on the back cover and ask, What are these? When do we use them? Have you ever stayed in a tent? Why? When? Why are there so many tents in the picture? Where do you think it is? Why? Before reading, we can make use of the think-pair-share technique to ask the children what they would put in their own bag for a very long journey. They can draw the items and use their drawings to notice and compare the items in the child’s travel bag while reading.

I highly recommend this picturebook for the meaningful journey it takes children on whilst raising their awareness of war and conflict around the world and the impact on people’s everyday lives.

Sónia Ferreirinha is a primary English teacher, a teacher trainer and a board member of the Portuguese Association of Teachers of English – APPI. She is also Director of the APPI CPD Centre and Coordinator of APPI Young Learners Special Interest Group – APPInep.

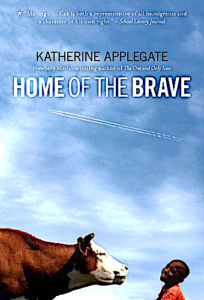

Applegate, Katherine (2008). Home of the Brave.

New York: Square Fish.

Recommended by Heidi Haavan Grosch

What does it mean to call a place home? For Kek, a ten-year-old boy who has lost most of his immediate family during the Sudanese civil war, this means redefining home in Minnesota USA – a world apart from his early childhood experiences. In his new life with his aunt and cousin, Kek learns to negotiate wonders such as a washing machine, chocolate milk, and grocery stores. At school, he joins an English as an additional language class and learns what it means to become American. He misses the familiar cattle herding of rural Sudan, so when he sees a decrepit cow alone in a field, he knows he can help. Gol, the cow, becomes a symbol of starting anew and helps Kek as much as he helps her. The message of Applegate’s verse novel is that for refugees, hope comes in many forms and for the young reader, Kek’s character serves as an important and timely reminder that the world does not always have to be a dark place.

Applegate uses colourful language for Kek’s dialogue, he sees an airplane as a ‘flying boat’ (p.10) and the metaphors and similes of the verses help to situate his new experiences in more familiar contexts. A pile of papers becomes a termite mound (p. 56) and chocolates, jewels in the sand (p. 119), enabling children to shift perspective by seeing through words what Kek is feeling. The African proverbs used to introduce each verse can be explored by children in groups for the messages they convey. Verses can also be used as springboards to inspire and scaffold children’s creative writing such as ‘hope is…’ (p. 246) or ‘hunger is…’ (p. 150), and ‘once there was…’ (p. 64).

The book is accessible and relevant for lower secondary learners of English who could do project work around Kek’s background as a member of the Nuer people in South Sudan. Raising children’s awareness of the ‘Lost Boys of Sudan’ also provides rich context such as working with short clips from the 2003 PBS documentary of the same name https://pbsinternational.org/programs/lost-boys-of-sudan/ Collaborative online research, where children investigate and orally present the work of international organizations such as Kiva https://www.kiva.org/ and the UN Refugee Agency https://www.unhcr.org/, can foster deeper understanding, empathy and a new perspective on the global refugee situation.

Heidi Haavan Grosch has been using children’s literature as a teacher and performing artist for almost four decades. She currently works in teacher education at Nord University, Norway and collaborates closely with local primary and secondary schools. Her YouTube channel CyberBridge: tips and tricks for teachers in grades 1-10 is now in its third season.

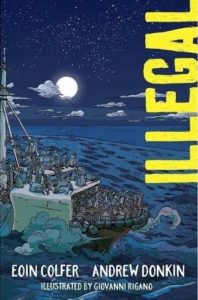

Colfer, Eoin & Donkin, Andrew (2017). Illegal.

London: Hodder Children’s Books.

Recommended by Liz Hibberd

Illegal is a graphic novel by the Children’s Laureate of Ireland, Eoin Colfer and children’s author and graphic novelist, Andrew Donkin, illustrated by comics artist, Giovanni Rigano. The plot powerfully charts the journey of 12-year-old Ebo as he leaves his home in Niger to find his siblings and make a new life elsewhere with more opportunities and less poverty. The fictional story follows Ebo as he leaves his village and travels across the Sahara to Libya and on to Europe. Throughout, he experiences hardships and challenges, making choices and decisions which no child should ever have to face. Putting his life in the hands of traffickers and as the title suggests, he relies on working illegally to make enough money for his passage.

Giving a face to the many children experiencing this harsh reality around the globe, the book explores the complex and nuanced reasons why people flee their homes and undertake perilous journeys. It does so unflinchingly, but also with considerable humanity, while the captivating visual panels present the young reader with an accessible vehicle to explore illegal child labour. The authors successfully avoid being didactic and instead, ask the reader to take time to listen without making snap judgements of the characters. Ending with the stark reminder that in 2015, one million people crossed to Europe via the Mediterranean, as well as the entreaty – with particular resonance for the current pandemic – every person is first and foremost a human being.

Written from Ebo’s perspective and via his thoughts, the sparse language and accompanying illustrations clearly communicate the plot and spark the readers’ curiosity. We could use this graphic novel with English learners, aged circa 15 to 17 as a springboard for perspective shifting. Teenagers could work in groups to carry out collaborative web-based research, thereby developing information literacy. This would lend itself to a jigsaw type communication activity where groups each take a different aspect, such as: ways to improve refugees’ situations in their home countries, the challenges and barriers they face while travelling, the discrimination encountered on arrival in new countries. After researching, learners can create information posters / infographics to share their discoveries in a learner-centred and engaging manner. To enable teenagers to challenge the rhetoric and propaganda associated with trafficking and forced child labour, teachers could supplement work on Illegal in English lessons with freely downloadable lesson plans from The NO Project, https://www.thenoproject.org/lesson-plans/ in particular, Something Doesn’t Feel Right, Cocoa Truth, Gold Costs More Than Money, Carpet of Dreams, The Letter. I recommend this graphic novel for its affordances as a story of resilience, heartbreak and determination. It highlights the plight of refugee children around the world in a teen-accessible manner whilst shining a light on one child’s journey, expertly weaving despair, hope and reality.

Liz Hibberd currently works for two charities supporting refugees and asylum seekers in Manchester, United Kingdom. She delivers social activities to provide those seeking sanctuary with the space and opportunity to engage with the local community, develop positive networks and promote wellbeing. Liz previously worked in refugee camps in Ethiopia, France and Greece.

Rosen, Michael & Young, Annemarie (2016). Who are Refugees and Migrants? What Makes People Leave their Homes? And Other Big Questions.

London: Wayland.

Recommended by Rebecca Warren

Why do people leave their homes? What is culture and how do we share it? What human rights should everyone have? These are some of the ‘big questions’ explored in Michael Rosen’s and Annemarie Young’s colourful information book about what it means to be a migrant and refugee. It is appropriate for secondary learners aged 13-17 and could be used in English lessons via a CLIL-type approach. The non-fiction text is written in a similar style to a school textbook and includes seventeen sections each on a different topic including international migration, asylum, human rights, identity, culture, integration and global citizenship. Topics are illustrated by vivid photographic images of the refugee experience, such as contemporary images of Syrian families fleeing the war and crossing the Mediterranean Sea, and historical images of Jewish children persecuted during World War Two. Each section includes unique case studies about people and/or their relatives who have migrated to the United Kingdom on a forced or voluntary basis, making the book an ideal vehicle for intercultural learning in ELT. Some of these case studies include famous people in the media, writers and athletes to show the significant contributions migrants and refugees can make to a country that welcomes and nurtures them, and thereby to develop empathy on the part of the reader.

The book can be used as a catalyst for meaningful project work in secondary English lessons. For example, students can research their own family histories or create case studies about people who have left their countries to seek refuge in another, using the book style and layout as a template for presenting this research. Students could also interview or make vox pops about people at school or in their community who migrated to their country, either on a forced or voluntary basis. Students could create a presentation, film, poem or story about the Human Rights Convention or another topic from the book, to share with students in other classes.

At the end of each section of the book, there are prompt questions for readers to think deeply about and discuss. These can used in ELT for pyramid discussion or debates, thus encouraging students to use the topics to analyze different sides of an argument, develop and express their own opinions and ideas. In summary, Rosen and Young’s book provides teachers with an engaging resource to enable teenagers to critically think about these increasingly significant issues in the context of English language learning.

Rebecca Warren is a teacher, youth worker and researcher. She has worked with refugees and asylum seekers for ten years in the United Kingdom and Thailand. Rebecca is completing doctoral research into the educational experiences of young refugees in Bangkok, Thailand. She is also a curriculum advisor for Cedar Learning Centre, a school for young refugees unable to access mainstream education.