| Nicola Daly

Language, Identity and Diversity in Picturebooks: An Aotearoa New Zealand Perspective New York: Routledge, 2025, 129 pp. ISBN: 978-1-032-53403-9 Reviewer: Nayr Ibrahim

|

Download PDF |

Overview of Picturebooks in ELT

Picturebooks in English Language Teaching (ELT) are powerful tools for fostering authentic language experiences, encouraging intercultural understanding and addressing underrepresentation. Hence, it is fitting that the main theme running through Daly’s Language, Identity and Diversity in Picturebooks: An Aotearoa New Zealand Perspective is Sims Bishop’s (1990) ‘mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors metaphor’, as it explores the linguistic diversity of the Aotearoa New Zealand context through its picturebooks, histories and languages. The book mainstreams the (multi)linguistic aspect of picturebooks while exploring Indigenous stories, themes and knowledges and provides the reader, the researcher and the teacher with the scaffolds and terminology to express the multilingual identity of children’s literature.

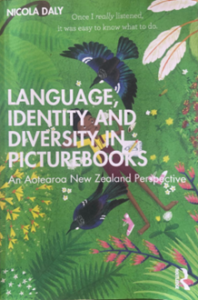

Foregrounding the ‘picture’ in picturebooks, the front cover shown above acts as an invitation to Aotearoa through the very distinctive features of its landscape: the evergreen forests, fern leaves, white toetoe fronds, yellow kōwhai flowers, póhutukawa (aka ‘Christmas tree’) branches and the two tūī birds in flight. The boy lying on the green grass is not reading but dreaming, imagining, creating, listening – a clear reference to the impact of stories beyond a book’s physicality. This front cover is a full-page illustration from the picturebook, The Bomb/Te Pōhū, written by Sacha Cotter and illustrated by Josh Morgan who gave Routledge permission to use the image. The Bomb/Te Pōhū was Supreme Winner of the Margaret Mahy Book of the Year, New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults in 2019.

A Walkthrough of the Content and Structure

The book consists of eight chapters, including the introduction and conclusion, and is divided into two parts. Part 1, Linguistic Landscapes and Language Hierarchies, addresses picturebooks as artefacts with a focus on their multimodality, textual-visual encounters and design decisions, with far-reaching implications for addressing language hierarchies, revitalization and the positioning of minority and indigenous languages. Part 2, Pedagogical Potential of Picturebooks, explores dual language picturebooks as pedagogical resources from a social justice, identity and diversity perspective.

As a book about dual-language picturebooks in a multilingual society, in which an Indigenous language has had to fight to survive, it is only fitting that the Māori language is present. Te Reo Māori appears in the title and numbering of each chapter and always precedes English. For example, Tahi (1) He Timatatanga – Introduction opens with the author’s pepeha, a traditional Māori introduction that honours connection to the land and its ancestors. These carefully chosen design elements are deliberate decisions that contribute to sustaining the revitalization efforts of Te Reo Māori, increasing the status of the Indigenous language that is positioned as a prestigious language alongside English, and compelling academic engagement with dual-language children’s literature.

This introductory chapter gives a detailed historical overview of children’s literature in Aotearoa New Zealand, interweaving the publishing, educational, policy and academic fields, including researching and teaching children’s literature at universities. Daly describes the waves of support for the revitalization of the Māori language as a distinctive Māori New Zealand voice that emerged in the 1980s. This journey includes significant milestones in the form of key publications, for example, the dual-language classic, Kuia and the Spider (1981) by Patricia Grace and Robyn Kahukiwa; the role of key literary figures, such as Joy Cowley; the establishment of Huia Publishers in 1991, dedicated to publishing books in Te Reo Māori, which impacted positively on the number of books published in the language; and the burgeoning and yet inconsistent academic study of children’s literature. Daly concludes the chapter with a defense of her focus on researching the language(s) of picturebooks, while acknowledging the interconnection of word and picture to fully tell the story: ‘It is the involvement of images that allows (or requires) the languages used to be brief and succinct and also allows the inclusion of several languages, as the images support meaning-making if a language is unfamiliar’ (p. 13).

The next two chapters take the reader into the picturebooks themselves. Chapter Rua (2), focusing on Māori words in predominantly English texts (translingual picturebooks) explores how and why the increasing presence of Māori words supports the visibility and revitalization of Te Reo Māori. It also increases knowledge of cultural practices, instigates curiosity in the language and its sounds and consolidates a national identity for New Zealanders inside and outside the country. A particularly valuable contribution is the ‘Typology of Dual-Language Picturebooks’ (p. 34) in chapter Toru (3), which offers a clear terminology and framework, accompanied by a pictorial explanation, of dual-language picturebook types. The chapter then explores the design decisions from the author, publisher and readers’ perspectives, through a linguistic landscape lens, amply exemplified with bilingual picturebooks from New Zealand.

Chapter Wha (4) explores the interaction between linguistic landscapes and language hierarchies in two international locations: the Marantz Picturebook Collection, at Kent State University (USA) and the Internationale Jugendbibliothek (IJB) in Munich. Daly’s quantitative study of 211 dual-language Spanish English picturebooks in the Marantz collection highlights the dominance of English. Despite the presence of Spanish, its positioning in terms of the space given to the language, the order of the languages and the size, colour and typeface of the text relegate Spanish to a secondary position with a mere symbolic informational function. Daly’s investigation of 24 multilingual picturebooks at the IJB highlighted, once again, the predominance of dominant European languages targeting a domestic audience. An interesting aspect of these multilingual books was the presence of different scripts, which were mostly a decorative element rather than a meaningful orthography. Daly emphasizes the importance of considering the developing attitudes of children confronted with these language hierarchies that do not decentre and destabilize the status quo of dominant versus minority languages. Daly ends Part 1 with design suggestions for authors, publishers and designers, to avoid privileging one language over another, especially when one is a minoritized language.

In Part 2, Chapter Rima (5), Supporting Identity and Diversity, explores two overall themes. First, Daly describes the creation of a New Zealand Picturebook Collection, which reflects national identity through the themes of family or intergenerational whānau, Māori traditions, beliefs and lifestyles, while connecting to other cultures and addressing universal themes. The second theme explores the positive impact of picturebooks in the home languages of refugee children and Pacific communities: children demonstrate higher levels of engagement and increased confidence and express joy at seeing their home language in books. A pedagogical intervention in a Pacific kindergarten highlights the importance of the teacher’s belief in the power of picturebooks and how the books can help empower children’s voices, even when the teacher does not share the same cultural background. Daly acknowledges the difficulty in sourcing picturebooks about minoritized groups and stresses the need to move the spotlight onto these books by encouraging or demanding diversity from large established publishers and creating awards that focus on such picturebooks.

Chapter Ono (6) Dual-language Picturebooks and Adults, explores the adult response to picturebooks in three tertiary settings. Firstly, a study with teacher educators in New Zealand looked at ‘why’ and ‘how’ they used picturebooks, which included connecting with the child in the adult learner, modelling pedagogy, making links to community, culture and language, developing visual analytical skills and discussing social and cultural issues. A weekly picturebook club at the University of Arizona underscored pre-service teachers’ lack of awareness of such picturebooks. In the third study, pre-service teachers on a bachelor’s degree course responded to the use of picturebooks as a resource for exploring language contact, such as translanguaging. Furthermore, student and educators’ responses highlight key features of picturebooks, such as brevity and clarity of the text as well as the supporting role of illustrations for understanding. Chapter Whitu (7) Dual-language Picturebooks and Children, focuses on language learning and learning about language with children in primary and kindergarten contexts and their parents. Various studies highlight techniques for using these texts to support multilingualism and multiliteracy, such as translanguaging, linguistic mediation, multimodal reading, and metalinguistic activities. A key aspect of this chapter is the parents’ voice, in acknowledging the knowledge they have and their own journey of discovery of dual-language picturebooks and ways they can support Te Reo Māori in the family context.

Final thoughts and conclusion

The concluding chapter refers to another metaphor that I particularly appreciated. Dual language picturebooks are described as a trojan horse, as they are seen as ‘harmless and inert [yet] can bring powerful ideas into homes and classrooms’ (p. 111). Through multiple studies across varied contexts, Daly highlights an important aspect of multilingual picturebooks: the multilinguistic landscape as a research and pedagogical lens to address inequalities, power imbalances and linguistic hierarchies in society. By embedding Te Reo Māori into the very fabric of the publication, Daly not only normalizes the presence of multiple languages in academic publishing but elevates the Indigenous language through culturally sensitive and sustaining approaches in the interconnections of text, picture and design.

Daly’s research journey – spanning international collaborations, academic projects, and personal connections – emphasizes the value of intercultural exchanges and transknowledging (Heugh, 2021). For New Zealand readers, the book acts as a mirror, reflecting their national identity and linguistic heritage. For non-New Zealand readers, it serves as a window, offering access to an often-overlooked multilingual and Indigenous context. This duality underscores the universality of the book’s themes, making it a significant contribution to global children’s literature and education.

If there are any shortcomings, I would tentatively suggest the need for more explicit classroom strategies to systematically integrate dual-language books into everyday teaching practices, with a greater emphasis on the visual elements of picturebooks, particularly Indigenous scripts and illustrations. I would also recommend a deeper discussion around the publisher’s design decisions, for example, the importance of maintaining the integrity of the front cover illustration as a sign of respect and acknowledgement of whenua, place, and iwi, people. In the version currently available on the Routledge website I am dismayed at the presence of a dark blue band across the illustration, cutting it in half, covering up part of the iconic references to Aotearoa. This is reminiscent of a western band-aid insensitively and unceremoniously plastered on an Indigenous scene, colonizing the very essence of the publication, for what purpose, I wonder!

While the book is not explicitly tailored for ELT, its insights are invaluable for educators and researchers in the field. It advocates multilingualism, Indigenization, and equity in education – essential values for contemporary classrooms. I would advocate for more of these ‘trojan horses’ to enrich the ELT landscape and foster a deeper appreciation of linguistic and cultural diversity.

Bibliography

Cotter, Sacha, illus. Josh Morgan (2019). The Bomb/Te Pōhū. Huia Publishers.

References

Heugh, K. (2021). Southern multilingualisms, translanguaging and transknowledging in inclusive and sustainable education. In Harding-Esch, P. with Coleman, H. (Eds). Language and the Sustainable Development Goals (pp. 37–48) British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/L024_EnglishforEducationSystems_DakarConferenceProceedings_Web_FINAL_April2021.pdf

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors, Perspectives: A Review Journal of the Cooperative Services for Children’s Literature 6(3), ix-xi. https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf

Nayr C. Ibrahim is Associate Professor of English Subject Pedagogy at Nord University, Norway and leader of Nord’s Children’s Literature in ELT Research Group. She is also treasurer of the Early Language Learning Research Association and co-author of Teaching children how to learn, Delta Publishing. Her research interests include early language learning, learning to learn, bi/multilingualism, language and identity, children’s literature, and children’s language rights.