| What Do You Do With Hands Like These? Close Reading Facilitates Exploration and Text Creation Lindsey Moses |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This article shares instructional ideas to enhance language and literacy experiences involving the reading and writing processes of young bilinguals (Spanish and English) in Colorado, USA when engaging with informational texts. Informational texts provide language scaffolds for young bilinguals because they build on their background knowledge about the world around them. Drawing on their recognition of real-world concepts found in informational texts, teaching ideas that enrich both academic and social vocabulary are shared. These teaching ideas suggest moving beyond the read aloud and individual reading of informational texts; they suggest instead teaching young learners to ‘read like writers’ and utilize Jenkins and Page’s What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? (2003) as a mentor text. This article includes relevant research, teaching ideas and classroom examples for scaffolding a close reading, ultimately resulting in intercultural explorations as the children share their writing about their home contexts.

Keywords: English Language Learners (ELLs), Close Reading, Informational Text, Mentor Text

Lindsey Moses (PhD) is an Assistant Professor in Literacy in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University. Her research interests include sociocultural perspectives on language and literacy instruction and learning among young bilinguals. [End of Page 44]

Introduction

Children’s literature can play a vital role in English language education by providing access to imagined worlds and relatable experiences, intensifying information about the world with exposure to rich language in quality literature. As English language learners (ELLs) engage in literary experiences, there is an opportunity to spark a love for language and literacy while simultaneously enhancing English language acquisition. Teachers can facilitate these interactions by thoughtfully selecting quality literature, planning detailed and meaningful instruction, providing guided practice and support, and facilitating independent exploration to connect the reading and writing experiences. This article shares instructional ideas to enhance language and literacy experiences involving the reading and writing processes for young bilinguals when engaging with the informational picturebook What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? (Jenkins & Page, 2003). All the ideas were tried out in a first-grade class of 24 six to seven-year-olds in Colorado, US. The first and home language of the bilingual young learners was Spanish.

Literature Review

Reading comprehension can be challenging for bilinguals, as documented by standardized assessments (NCES, 2011). This has been linked to limited target culture background knowledge and underdeveloped vocabulary in English (Bradley & Bryant, 1983; Hulme, Muter, Snowling, & Stevenson, 2004; National Research Council, 1997). Informational texts provide opportunities to build and improve what Jim Cummins (1979, pp. 121-129) has described as BICS and CALP: Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) during classroom conversations, and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) as the young bilinguals build on their background knowledge and gain an understanding of content vocabulary. As can be seen later in the Teaching Ideas section, the exploration of a mentor text with close readings can facilitate deeper understanding and meaningful conversations. Multiple researchers have documented the benefits of this type of engagement found in dialogic interactions and meaningful and authentic literary experiences (Schweinhart & Weikart, 1998; Beach & Myers, 2001; Gutierrez, Baquedano-Lopez & Tejada, 1999), yet the majority of instruction for ELLs remains focused on [End of Page 45] isolated skill instruction that emphasizes rote memorization (Allington, 1991; Darling-Hammond, 1995).

Engagement with informational texts has been reported to motivate young learners and encourage overall literacy development (Caswell & Duke, 1998). The definition of informational texts includes multiple sub-genres such as expository texts, literary non-fiction, almanacs, hybrid texts (e.g. The Magic School Bus series) and picturebooks. Substantial benefits have been documented for children who receive increased exposure, access and knowledge about informational texts (Pappas, 1991; Purcell-Gates, Duke & Martineau, 2007). In particular, bilinguals need reading material that is comprehensible at approximately their level of English language proficiency (Krashen, 1985; Rigg & Allen, 1989). The images, headings, text features, structure and length of informational texts provide optimal input (Greenlaw, Shepperson, & Nistler; Richard-Amato, 1996). With this optimal input, young bilinguals are able to construct meaning with informational text and can benefit from understanding literacy as an integration of reading, writing, speaking, listening, viewing and visually representing. This type of thoughtful exposure to and exploration of genres can provide a connected and supportive vision of reading and writing in English.

Duke (2003) reports that young learners who are exposed to particular genres, like informational texts, are able to reproduce them more successfully. The documented paucity of instruction and scarcity of interaction with informational texts in primary classrooms (Duke, 2003; Jeong, Gaffney, & Choi, 2010) puts children who are learning English at a disadvantage for gaining content knowledge, engaging in authentic literacy practices, acquiring academic and social vocabulary and writing in multiple genres. Utilizing engaging informational texts, scaffolding genre explorations, and providing opportunities for text creation with intercultural connections is one way to facilitate content knowledge and language acquisition.

Most informational texts for young readers involve multiple modes for interpretation, and children must attend to visual cues in addition to printed text. While there has historically been a focus on decoding, the notion of literacy has been expanded to encompass more than printed letters and text (The New London Group, 1996; Kress, 2010; [End of Page 46] Narey, 2009). As the current literacy demands require sophisticated meaning construction and navigation of complex texts, ‘one must reconceptualize the reader as reader-viewer attending to the visual images, structures and designs of multi-modal texts along with printed text’ (Serafini, 2012, p. 152). The following teaching ideas for a close reading of a mentor text provide considerations for language and literacy development for young bilinguals. In addition, the independent exploration and text creation facilitates opportunities for intercultural explorations as the children share their writing.

Teaching Ideas: Close Reading, Guided Exploration and Text Creation

The following ideas suggest moving beyond the read aloud and individual reading of informational texts, teaching young learners to utilize the picturebook What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? as a mentor text. A mentor text (Wood Ray, 2006) serves as a model for students to analyse and explore in preparation for writing in a specific genre. In this way, young learners’ experiences of a close reading, guided exploration and text creation can be supported. Close reading requires multiple exposures to a text in order to comprehend, reflect and critique. The initial reading is intended to support comprehension and general understanding of the picturebook. The second reading includes reflection and analysis about how the text is structured, how information and evidence are presented. The third reading draws on the knowledge constructed from the first two readings to support a critique of text content and aesthetics, and discover connections to other texts and the children’s lives. In the following sections, documented classroom experiences with the mentor text What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? are shared. Suggestions are provided for scaffolding vocabulary, supporting critical thinking, and studying the non-fiction genre in order to connect to writing. Finally, ideas for independent exploration and creation of informational text are provided that encourage ELLs autonomy and connections to their home contexts. This lesson was taught with an elementary classroom, but it could easily be adapted to work with other grades (a similar lesson sequence with this text has been used in a college writing course). The vocabulary and scaffolding can be adjusted according to the young learners’ language and literacy proficiency levels. [End of Page 47]

Initial reading

The first reading began by drawing attention to the cover and asking the young learners what they noticed. The teacher provided time for discussion related to the visual design elements, title, author and illustrator, and told the children that they would be paying particular attention to what the author and illustrator did. As the book was read aloud, the teacher drew attention to the information about tails, feet, eyes, ears, mouths and noses. What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? is perfect for supporting language and literacy acquisition because it makes use of repetitive text with the question preceding the facts about each body part, encouraging the children to guess the animals. The pages can be read as an interactive read aloud, and the young learners invited to chime in:

What do you do with feet like these?

If you’re a chimpanzee, you feed yourself with your feet.

If you’re a gecko, you use your sticky feet to walk on the ceiling.

If you’re a mountain goat, you leap from ledge to ledge. (Jenkins & Page, 2003).

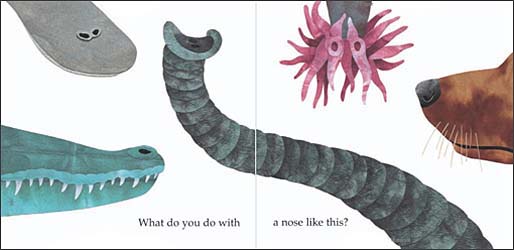

Figure 1: Illustration from What do you do with a tail like this? Steve Jenkins and Robin Page. Copyright 2003 by Steve Jenkins and Robin Page. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. [End of Page 48]

Next, the teacher pointed to the illustrations, inviting the children to talk about how other animals used the same body part. The teacher encouraged them in sharing ideas in their first language. Providing time for this discussion helped lower their affective filter (Krashen, 1982), as the young learners felt less intimidated to consequently express their thinking in English. After the read aloud was completed, the teacher turned to the reference section at the end of the story and explained to the children that this section included additional information about the animals in the text. She asked them to share with partners what they had learned, and together they brainstormed the different body-part categories and entered them on a chart utilizing visual cues.

Second reading

For the second reading, the young learners built on their prior discussion about the text, information in the text and newly acquired vocabulary. In order to do this, the teacher revisited the chart made during the first reading to provide additional vocabulary support to scaffold the reflection. She told the ELLs they were going to be rereading What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? – but this time they should keep the following questions in mind as they participated in the read aloud:

- How is the text organized?

- How is information presented?

- How is the information in the illustrations explained?

The teacher read the introduction and first section about noses and asked the children to discuss what they noticed about the way the text was organized. The children identified the following characteristics:

- On the first double-page spread there is a question about what you can do with a nose like this and illustrations of animal noses;

- On the following double-page spread there are illustrations of entire animals and what they do with their noses;

- The animal illustrations are all accompanied by an explanation: ‘If you’re a (name of animal), you use your nose to…’ [End of Page 49]

Figure 2: Illustration from What do you do with a tail like this? Steve Jenkins and Robin Page. Copyright 2003 by Steve Jenkins and Robin Page. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

The children found the repetitive organizational structure clear, so the teacher continued to scribe their comments onto a wall chart as they successfully identified the patterns in the text. After this examination and response, the class continued reading the text and making notes on a wall chart so that they could see and easily revisit the concepts. This second reading provided opportunities for ELLs to develop and recycle content-specific vocabulary while also encouraging a great deal of talk with peers. This type of low anxiety interaction facilitates the development of BICS and CALP (Cummins, 1979) while simultaneously introducing children to close reading and ‘reading like a writer’.

Third reading

To begin the third reading, the teacher reminded the young learners to ‘read like a writer’ because they would be using this book as a mentor text to create a class book in the informational text genre. During the third reading, the children referred to and drew on the information from the first two readings (charts on content, charts on organization, charts on information) in order to support their critique of the following:

- The quality of the text with regard to arrangement of content

- The quality of the text with regard to aesthetics [End of Page 50]

- Connections to other texts and the children’s lives

The teacher created three new charts with a heading for each of the bullet points and explained to the children that they would be considering these aspects during the reading. After reading the first of the text, she asked them to talk to a peer about the arrangement of content. Some responses included that the author and illustrator wanted to share information about how animals use their body parts, they wanted to make the information interesting by using illustrations, or they wanted the reader to seek more information about intriguing animals. When discussing the quality of the text with regard to aesthetics, the teacher wanted to encourage the ELLs to move beyond, ‘I like the book’. She asked them to share with partners and the class what writing and illustrative techniques they found enhanced the quality of this informational text. The teacher encouraged the young leaners to closely analyse the visual design elements as well as typography and illustrative techniques and documented their noticings on the chart. For the completion of the third reading the teacher asked them to discuss connections to other texts and to their own lives. She reminded students that their connections to other texts could include both narrative and informational texts. The teacher then documented the class discussion on the final chart.

Guided Exploration and Book Creation

This section provides an example of class book creation. The guided exploration and creation built on the children’s receptive understanding, analysis and reflection in order to support their expressive production in writing. The teacher again revisited the charts from the close readings and asked the ELLs to reflect on their noticings. She explained they would be using the information gained from the close reading as a mentor text to each create their own page for a class book. The teacher explained that their illustrative techniques could be similar to those found in the mentor text, or other options included photography, charcoal, oil pastels, watercolor, markers, paint, computer drawing programs, etc. As a class, they brainstormed ways that they use their body parts when they are in school. Table 1 shows the student-generated ideas. [End of Page 51]

Table 1

| Question | ELLs responses |

| What do you do with hands like these? | write, paint, draw, clap, count, build |

| What do you do with ears like these? | listen to stories, listen to friends, listen to the teacher, listen for the bell |

| What do you do with eyes like these? | read, watch my friends, watch my teacher, watch the ball |

| What do you do with feet like these? | put them crisscross on the carpet, walk down the hall, line up, dance, run, kick the ball |

| What do you do with mouths like these? | talk, read, sing, laugh |

The young learners then broke into groups according to the question and number of generated responses. They each created an individual page that included a photograph of themselves using their featured body part and a sentence about their photograph and response to the question. Figure 3 is a photograph of Maria (pseudonym) drawing and writing and was accompanied by the following text, ‘If you’re Maria, you use your hands to write and draw’.

If you’re Maria, you use your hands to write and draw.

All of the contributions were compiled into a class book that became part of the classroom library. The children focused their first book on body parts and the classroom, [End of Page 52] but many adaptations of this could be created by altering the topic, format, illustrative technique, etc.

Independent Exploration and Creation

Once the class book was completed with guided practice, the teacher invited the young learners to experiment with independent exploration and creation by creating their own individual books. Many children chose to do this around their family, utilizing the same format of body parts. The teacher encouraged them to create bilingual texts, when possible, in order to share their work and home contexts with both their school and home communities. Other children created books about athletic teams/clubs, community centres, after school programs, and community spaces. When the children had completed their books, they had an author celebration in small or whole group settings depending on their comfort level. The options for self-selected topics were endless, and it allowed the children to feel their home and out-of-school experiences were valued and had a place in their literary development in the school setting.

Conclusion

Repeated close readings provide multiple benefits for young bilinguals. The repeated exposure to language and academic vocabulary assists in language acquisition in authentic ways because it is presented in context with supporting visuals and discussion. The comprehensible input, as a result of the images and the ability to draw on background knowledge about the world, scaffolds participation and comprehension. As seen in the lesson with first graders, ELLs were able to move beyond comprehension and recall in order to utilize the text as a mentor for creating their own writing about personal experiences. The young bilinguals had the opportunity to revisit the text on multiple occasions using different lenses of analysis and critique in order to ‘read like a writer’ and gain deeper meaning. These experiences were further enhanced by the large amounts of discussion in low anxiety settings that supported receptive and expressive development in English. [End of Page 53]

Informational texts can provide opportunities for this type of engagement with numerous themes, topics and text structures that can be used as mentors for exploration, text creation and connection to the world outside of school. Encouraging the use of their home language and English, in both discussions and individual book creations, demonstrates a value for children’s home language, culture and experiences. This provides opportunities for intercultural explorations and discussion about their lives. Additionally, it invites parents who may or may not speak English to participate in the creation and feel valued in the school community. Young bilinguals, as seen with these first graders, benefit from meaningful interactions with text, repeated readings, emphasis on vocabulary and language, critical thinking and analysis, and opportunities to speak, listen, read, write, view and visually represent. Engaging young learners with language and literacy in these contexts – with quality informational texts like What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? – helps set them up for linguistic and literary success.

Bibliography

Jenkins, S. & Page, R. (2003). What Do You Do With a Tail Like This? Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Cole, J., &, Degen, B. (1986- ). The Magic School Bus. New York: Scholastic Inc. http://www.scholastic.com/magicschoolbus/books/index.htm

References

Allington, R. L. (1991). Children who find learning to read difficult: School responses to diversity. In E. H. Hiebert (Ed.), Literacy for a Diverse Society: Perspectives, Practices, and Policies (Vol. 237-252). New York: Teachers College Press.

Bradley, L., & Bryant, P. E. (1983). Categorizing sounds and learning to read: A causal connection. Nature, 301(5899), 419-421.

Beach, R., & Myers, J. (2001). Inquiry-Based English Instruction: Engaging Students in Life and Literature. New York: Teachers College Press.

Caswell, L., & Duke, N. K. (1998). Non-narrative as a catalyst for literacy development. Language Arts, 75(2), 108-117. [End of Page 54]

Cummins, J. (1979) Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic interdependence, the optimum age question and some other matters. Working Papers on Bilingualism, No. 19, 121-129.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1995). Inequality and access to knowledge. In J. A. Banks & C. A. M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education (pp. 465-483). New York: Macmillan.

Duke, N. K. (2003). 3.6 minutes per day: The scarcity of informational texts in first grade. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(2), 202-224.

Greenlaw, M. J., Shepperson, G. M., & Nistler, R. J. (1992). A literature approach to teaching about the Middle Ages. Language Arts, 69, 200-204.

Gutierrez, K., Baquedano-Lopez, P., & Tejeda, C. (1999). Rethinking diversity: Hybridity and hybrid language practices in the third space. Mind, Culture, and Activity: An International Journal, 6(4), 286-303.

Hulme, C., Muter, V., Snowling, M., & Stevenson, J. (2004). Phonemes, rimes, vocabulary, and grammatical skills as foundations of early reading development: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 40(5), 665-681.

Jeong, J., Gaffney, J., & Choi, H. (2010). Availability and use of informational texts in second, third and fourth-grade classrooms. Research in the Teaching of English, 44(4), 435-456.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Available from:

www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_practice.pdf

Krashen, S. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. New York: Longman.

Kress, G. (1997). Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy. New York, NY: Routledge.

Narey, M. (Ed.). (2009). Learning Through Arts-Based Early Childhood Education. New

York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

National Center for Education Statistics (2011). The Nation’s Report Card: Reading 2011

(NCES 2012-457). Institute of Education Statistics, U. S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C. Available from http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pdf/main2011/2012457.pdf [End of Page 55]

National Research Council. (1997). Improving Schooling for Language-Minority Children. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Pappas, C. (1991). Fostering full access to literacy by including information books. Language Arts, 68(6), 449-462.

Purcell-Gates, V., Duke, N. K., & Martineau, J. A. (2007). Learning to read and write genre specific text: Roles of authentic experience and explicit teaching. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(1), 8–45.

Richard-Amato, P. A. (1996). Making it Happen: Interaction in the Second Language Classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Longman.

Rigg, P., & Allen, V. G. (Eds.). (1998). When They Don’t All Speak English: Integrating the ESL Student into the Regular Classroom. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Schweinhart, L. J., & Weikart, D. P. (1998). Why curriculum matters in early childhood education. Educational Leadership, 55(6), 57-60.

Serafini, F. (2012). Expanding the four resources model: reading visual and multi-modal texts. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 7(2), 150-164.

The New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Available from: www.pwrfaculty.net/summer-seminar/files/2011/12/new-london-multiliteracies.pdf

Wood Ray, K. (2006). Study Driven: A Framework for Planning Units of Study in the Writing Workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. [End of Page 56]