|

Who Are You? Racial Diversity in Contemporary Wonderland Rebecca Ciezarek |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Since its publication in 1865, Alice in Wonderland has established itself as a flexible text, translated into over 150 languages, and adapted across various media. In English-language adaptations, alterations to text and images have created a multitude of retellings, yet one aspect of the original story remains: that Alice is visually established as a Caucasian child. This paper examines three picturebook adaptations of Wonderland for how each of the new narratives reflects their culturally diverse readerships. The study of these adaptations is connected to research on literacy development, and culturally diverse classrooms, which show how diverse literature benefits all readers. With the 150th anniversary of Wonderland’s publication in 2015, this paper has a dual aim: to showcase the potential of Wonderland to act as an effective tool within classrooms to foster a sense of inclusion, and to demonstrate how future adaptations of Wonderland can be created which visually mirror their global readers.

Key words: Wonderland, racial diversity, adaptation, language, picturebooks.

Rebecca Ciezarek is a 3rd year PhD candidate at Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia, writing a thesis on contemporary picturebook adaptations of Alice in Wonderland. She has had work published in Screen Education, The Conversation, and the Journal of Language, Literature and Culture. Rebecca teaches Gender Studies and Children’s Texts at Victoria University. [End of Page 4]

Introduction

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has become one of the most translated and adapted stories in English literature. Carroll’s words and Tenniel’s illustrations have been reimagined, reorganized, and often removed, by new authors and illustrators who aim to create new versions of the story to suit changing audiences. Whether the change is focused around a particular scene or character (either physical depiction, or significance to the story), the physicality of Wonderland as a place, or narrative style and theme, Wonderland’s position as a work of imagination continues to inspire in terms of its possibility for transformation. Despite Wonderland’s nineteenth-century origins, there are elements of the story that project a sense of timelessness, and the opportunity to transcend language, social systems, and expectations of childhood. This sense of timelessness is reflected in the growing number of adaptations of the story, across the world, and across media. However, in conventional literary retellings of the story, despite the thousands of adaptations published since Carroll’s original story first moved out of copyright, one aspect remains largely unchanged: the representation of Alice as a Caucasian child.

When so much of Wonderland has been changed, it is worth considering why this element of Carroll’s story appears to be largely untouchable, and what this can mean for Wonderland’s culturally diverse child readers. This paper explores how contemporary picturebook adaptations of Wonderland can be used as part of multicultural education, using Banks’ (2010, p. 238) Additive Approach, whereby content, concepts, themes and minority perspectives are added to the curriculum without changing its structure. An awareness of Critical Race Theory is also embedded in the arguments presented here, as a method of highlighting the continuing privilege of white people, leading to the subsequent ‘othering’ of people of color (Hughes-Hassell, Barkley, & Koehler 2009, p. 5). Three Wonderland picturebook adaptations have been selected for this discussion, and all present racially diverse Alices, within culturally diverse contexts. These books are defined as ‘literary adaptations’ of Carroll’s story, as all three have been altered to make the story suitable for new audiences, and for a new purpose: to offer racially diverse protagonists. What this paper aims for is that through a discussion of these three stories, ideas of who Alice is can be expanded upon and reflect the diversity of readership in English language classrooms. Two of the adaptations re-tell Carroll’s story wholly or partly using dual [End of Page 5} languages, with differing results for readers: to create a community of readers who share the same language, and to provide other readers with insights into what makes diverse cultures unique.

Changing Alices and Literacy Development

Carroll’s Alice was influenced by a young child friend, named Alice Liddell, who was from a traditional White and well-positioned British family. Carroll’s choice of inspiration for his title character is not the focus here, beyond the fact that this Alice marked the beginning of what was to become an Alice industry (Susina, 2011), one which continues to revolve around perceived notions of who Alice should be. This notion positions the Alice who enters Carroll’s Wonderland, even when reinterpreted by a new author or illustrator, as not only White, but most often blonde. This is the continuing narrative of Wonderland, which remains even when much of the original story has transformed. With Carroll’s Wonderland not indicating Alice’s race, the principal reason for her continuing representation as Caucasian is arguably the previously mentioned perceived notion of who Alice should be, based on preceding images of a White-skinned Alice. Harris (1995, p. 277) discusses how ‘Whiteness is privileged, even in those instances when an alternative interpretation is warranted or valid’. This is arguably the case for Wonderland adaptations, considering the impact and influence of the story on a global scale. The history of Wonderland adaptations, however, is not adequate reason to forgo the potential for racial diversity, and instead contributes to the issue of the lack of diversity in children’s literature.

Alice’s journeys into Wonderland are ‘marked by near constant shifts and changes to both her bodily form and her social standing’ (Jaques & Giddens, 2013, p. 153). This paper does not aim to suggest that adapters of Wonderland are incorrect to present their Alice as Caucasian, as ‘all children, from all cultures and in all places, need to see books that reflect themselves and their experiences’ (Galda & Cullinan 2002, p. 275). Rather the paper questions the social narratives which influence authors and illustrators to otherwise willingly alter much of Carroll’s story, with the exception of Alice’s race. These social narratives have affects which reach into classrooms where adaptations of Wonderland can be found. [End of Page 6]

As bodily changes are essential to the story of Alice’s adventure, it makes sense for this potential to be used as a way of representing and including racially diverse characters. For such a well-known and adapted story, which offers much to children’s literacy development, it is a wasted opportunity not to embrace the potential Wonderland offers to showcase racial diversity through its title character, as one of the ways inclusive teaching can be achieved is through the presence of content on the histories, cultures, contributions, experiences, perspectives, and issues of different ethnic groups (Manning & Baruth, 2004, p. 210). This is how content can be made meaningful to students; however, meaning can also be made through seeing anew familiar faces in well-known literature.

How meaningful a book is to a child can be dependent on recognition of themselves within the story, and research shows that content which is meaningful to students improves their learning (Manning & Baruth, 2004, p. 210). As identified by Meier (2003, pp. 246-47), ‘books are not meaningful to children who do not see themselves represented in them [and] there is no more essential task for teachers in preschool and kindergarten classrooms than to help make books meaningful in children’s lives’. When personal meaning cannot be made, this can result in the learning experience within the classroom being more valuable for certain students, giving an advantage to children who come from cultures that are reflected within literature. Hefflin and Barksdale-Ladd (2001, p. 810) put forward a similar argument, describing how when readers ‘frequently encounter texts that feature characters with whom they can connect, they will see how others are like them and how reading can play a role in their lives. A love of reading will result’. This then leads to Galda and Cullinan’s (2002, p. 335) contention that ‘reading literature helps children learn to like to read; children then read more, and, in the process, become better readers and better language users’. When children are exposed to literature that as a collective tells different kinds of stories, the acceptance and appreciation of diversity expands, and all children benefit.

Adaptation and Diversity

Hutcheon and O’Flynn (2013, p. 95) cite the adapter’s deeply personal, as well as culturally and historically conditioned reasons for selecting a certain work to adapt and the particular way to do so. The culturally conditioned history of Western literature is one with [End of Page 7] a distinct bias towards White, able-bodied men, with regard to authors, characters, and implied readers. This is the acutely controlled past within which adapters approach Wonderland and create new versions, establishing unconscious parameters which dictate who should be represented, based on who has always been represented. That these parameters continue without question has negative impacts on the learning experience of young children, as outlined by Boutte, Hopkins, and Waklatsi (2008, p. 955). The authors explain that ‘without ongoing narratives that include diverse voices, White students will likely feel affirmed [that their status is the ‘norm’] and also internalize the message that the worldviews, values, and perspectives of people of color are abnormal’. In an analysis of transitional books, Hughes-Hassell et al (2009, p. 12) similarly cite that the message which comes from a lack of books featuring diversity, is that ‘it is better to be white’. Within an American context, Ramsey (2004, pp. 4-5) explains how on one hand children are learning that all people are ‘created equal’, and that there is a sense of ‘common good’, yet children are also learning in their daily experiences that ‘some groups are valued more than others and that it is acceptable to exclude people’. Exclusion and othering are connected to invisibility, which is in turn connected to value. If, as identified by Bryant (cited in Hutcheon & O’Flynn 2013, p. 95 [original emphasis]), adaptations are the ‘material evidence of shifting intentions’, then they also contain the possibility to shift ideas of value: who is valuable in a society, and who is visible.

Hutcheon and O’Flynn (2013, p. 4) emphasize the pleasure of recognition within a context of adaptation, along with remembrance, and change. Recognizing oneself in a piece of literature is discussed by C. Myers (2014), who draws attention to what he calls the ‘apartheid of children’s literature’, where despite the ‘bemoaning’ about diversity statistics, and publishers emphasizing their ‘commitment to diversity’, readers still find that characters of color ‘are limited to the townships of occasional historical books that concern themselves with the legacies of civil rights and slavery but are never given a pass card to traverse the lands of adventure, curiosity, imagination or personal growth’ (C. Myers, 2014, n. p.). This is a particularly poignant comment which strongly connects to Wonderland, in terms of the universality of the story, and the adventure, curiosity, and imagination it embodies. Cohen (1995, p. 140) discusses the universality of both Alice books, and how they can ‘affect all children of all places at all times in a similar way’. The [End of Page 8] affect comes from the emotional connection children can make with the stories, and how ‘they [the Alice books, R. C.] tell the child that someone does understand; they offer encouragement, a feeling that the author is sharing their miseries and is holding out a hand, a hope for their survival as they pass from childhood into adulthood’ (Cohen 1995, p. 140). The potential outcomes from this shared connection described by Cohen is explored by Hughes-Hassell et al (2009, p. 13) and defined as ‘text-to-self connections, a critical part of becoming proficient readers’. If this is what the stories can offer, and children can recognize themselves in the emotional journey Alice embarks on, it stands to reason that recognition can be further enhanced through a physical identification.

Adaptations can act as potential methods of engaging in larger social critiques, and ‘are not backdated but rather updated to shorten the gap between works created earlier and contemporary audience’ (Hutcheon & O’Flynn 2013, p.146, emphasis added). The inclusion gap is highlighted by a study conducted by the Cooperative Children’s Book Centre (CCBC) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison which found that of the 3200 picturebooks, children’s novels and non-fiction texts the library received in 2013, 93 contained a main or significant secondary character who is African or African American, 34 with American Indian characters, 69 with Asian Pacific, or Asian Pacific American characters, and 57 with Latino characters. This translates to approximately 92 per cent of the library’s 2013 book intake containing narratives where the most substantial characters are either Caucasian, or non-human. More troubling however is the 2003 CCBC report that shows figures higher than the 2013 report. These results suggest that diversity in children’s literature is declining, in spite of continuing research which affirms that ‘culturally authentic children’s literature engages the imagination and enhances the language skills of minority children’ (Pirofski, 2001, n.p.). It also suggests that despite the rise of multiculturalism in the West, which was created as a ‘vehicle for replacing older forms of ethnic and racial hierarchy with new relations of democratic citizenship’ (Kymlicka, 2012, p. 2), there remains a deficiency in the literary canon, and a continuing hierarchy confirmed by the underrepresentation of racial diversity. With readers around the world embracing the story of Wonderland, and being able to enjoy the written narrative, illuminated in their own language, how is it be explained that despite the universality of the text, the images remain predominantly mono-racial? [End of Page 9]

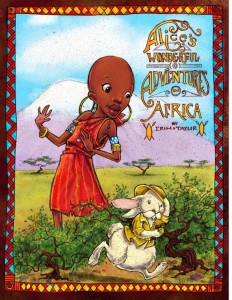

Erin Taylor’s Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa

Figure 1. Front cover of Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa by Erin Taylor

Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa was self-published in 2012, and inspired by Taylor’s time spent living in South Africa and Botswana. The story is set in an unspecified area of Africa, and Taylor’s Alice is a young African girl. As with the two other adaptations discussed in this paper, one of the ways Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa differs from other literary adaptations of Wonderland is the location of Alice’s adventure. Alice moves, not through a Wonderland, a Dreamland, or a Looking-Glass world, but through a real place. Young readers of Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa can look on a map and see where Alice is in comparison to them, they can read about the African jungle, or Savannah, and find out more about the languages spoken, and the cultural stories and behaviors enacted by the characters Alice meets. The story operates then as a type of educational tool, introducing children to both the diversity and difference of African cultures. In this way, Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa connects with Galda and Cullinan’s (2002, p. 7) contention that ‘literature entertains and it informs’. Literature ‘enables young people to explore and understand their world. It enriches their lives and widens their horizons’ (Galda & Cullinan, 2002, p. 7). It is important to remember when reading Taylor’s adaptation however, that because of its amalgamation of African cultures, it does not distinguish between the peoples of Africa. Pinto (2009, p. 103) describes how Africa is not one culture or people, but a ‘myriad of peoples and tribes, […] home to a great many cultures and to a thousand or more languages’. These distinctions need to be highlighted; otherwise the power of re-situating a new Alice in a new, real Wonderland is diminished. The Africa depicted in the story however can also be viewed as a Wonderland in terms of the characters, and the physical transformations Alice experiences. The narrative is a [End of Page 10] combination of both Alice books, and African cultural and ancestral stories, and this allows Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa to act as a fantastical story juxtaposed with realism.

Figure 2: Opening 14, Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa. Erin Taylor, 2012

Figure 2: Opening 14, Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa. Erin Taylor, 2012

There is no mention in Taylor’s written narrative of Alice’s appearance. Her clothing is described, as she uses it as a place to store the pieces of mushroom which play a significant part in the story. Beyond this, it is the illustrations which show the reader who this adapted Alice is. Her skin is dark brown; she has full lips, and wears large gold hoops pierced through the top of her ears. She is barefoot, and is clothed in a kikoi, an African sarong, made of red fabric, woven with gold thread. Two of the most striking features of Alice are her red eyes, and bald head. This particular feature of the illustrated Alice creates an intriguing scene with the Hare at his Tea Party, when he tells Alice, ‘Yah hair needs plaiting’ (Taylor, 2012). A change in perspective from the Hatter’s original comment of ‘Your hair wants cutting’, yet curious as Alice has no hair to either cut or plait (Carroll, 2003 [1865], p. 60). Although the story is written in English, the reader learns [End of Page 11] Alice speaks Swahili, and various words of African origin are interspersed throughout the narrative. However, Taylor’s (2012) Alice is bilingual, and in order to converse with several of the characters she meets in Wonderland, Alice is required to speak English.

Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa (2012) relies on an interconnected written and visual narrative to tell the story of Alice’s adventures through the African jungle and savannah. Sipe (2012, p. 5) discusses how in picturebooks two different sets of languages are created: ‘the language (in the usual sense) of the sequence of words and the language of the sequence of pictures’. The relating of words and illustration work to enhance a child reader’s understanding of not only the story, but also the foreign elements of African culture referred to throughout the written narrative. However, without the illustrations, readers of Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa would still remain aware of how this adventure differs from Alice’s in Carroll’s Wonderland. The written narrative is punctuated with words from the Swahili language. As Alice wanders through her African wonderland, she greets the creatures she meets by saying ‘Jambo’, which the reader is informed is a Swahili welcome (Taylor, 2012). A translation can also be derived from Alice’s shift to English when the first creature she attempts to converse with, the mouse in the pool of tears, does not respond to her initial greeting, and she tries to elicit a response with ‘Hello’. Alice’s bilingual skills are further demonstrated when she meets the Hatter and Hare at their tea party. She is admonished by the Hatter for seating herself at the table without being invited, and responds with ‘Sikitiko – I’m sorry’, and in farewell as she leaves the party, Alice says ‘Asante, thank you’ (Taylor, 2012). Incorporating multiple languages within a picturebook acknowledges the diversity of its readership, and shows an awareness of our global society. As described by Robles de Meléndez and Beck (2013, p. 251), ‘language is one characteristic that defines human diversity’, and can be used in literature for young children to demonstrate both this diversity, and the similarities across cultures. This benefits child readers, whether they encounter examples of cultural diversity in their daily lives, or their lived experience is dominated by one hegemonic culture.

Replacing objects and aspects of the environment, physically, and by name, to reflect Alice’s changed location is a further way the written narrative establishes Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa as an alternative Wonderland. The bank on which Alice sits with her sister, and where she first sights the White Rabbit, has been replaced with the [End of Page 12] ‘vast land of Africa’, and rather than becoming restless while listening to a story, as the sun rises Alice has been hard at work collecting firewood (Taylor, 2012). The reader learns that Alice lives in an Enkang, a Maasai word for village, and fantasizes about running away to have her own adventures where she will be free from the responsibilities of home. One of these responsibilities is to watch over the goats, and this is where another alteration of the story occurs in order to better fit with Alice’s repositioning as a young, African girl. Her cat Dinah, whose reference by Alice causes some grief to the animals of Wonderland in Carroll’s story, has been transformed into a favored goat.

Through the inclusion of African languages and descriptions and illustrations of objects of African origin, one of the ways Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa speaks to its readership is by acting as a source of information, a teacher of African cultures. At the Hatter and Hare’s tea party, the sleeping Dormouse is woken by Alice, who insists it tell her a story. The story the Dormouse shares belongs to the Asante peoples of the former Gold Coast, now Ghana, and tells a story of Anansi the spider, described by Marshall (2007, p. 31) as a ‘trickster figure and culture hero’ who appears in many myths. This story is ‘Anansi Owns All Tales That are Told’, telling of how he duped the Sky God to become the owner of all the tales in the world (Pinto, 2009, p. 103).

While clearly recognizable as Carroll’s story, Taylor’s adaptation offers more than a conventional retelling. This is done through resituating the adventure within different cultures, and recreating Alice as a citizen of the culture now presented as Wonderland. Goodman and Melcher (1984, p. 200), within an educational context, discuss the ‘growing awareness of the interrelatedness of the peoples of the world’. Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa demonstrates this awareness, and how it is possible to use Wonderland as a tool to showcase diversity in children’s literature.

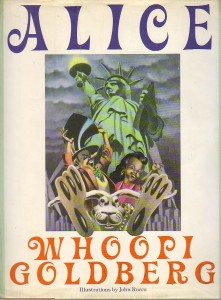

Whoopi Goldberg’s Alice

Figure 3. Front cover of Alice by Whoopi Goldberg.

Goldberg’s Alice (illustrated by John Rocco) was published in 1993, six years before the made-for-TV film adaptation of Wonderland Goldberg starred in. Alice is not a straightforward adaptation of Wonderland, but rather familiar elements of Carroll’s story have been interspersed within an essentially new narrative. Goldberg’s story begins in New Jersey, although the majority of the action takes place in New York City. Alice’s adventure [End of Page 13] is not precipitated by the arrival of the White Rabbit, the subsequent curiosity about him, and Alice’s literal stumble into Wonderland. Instead, Alice’s motivation is primarily based on greed, with her desire to claim a curious prize that a letter in the mail has informed her she has won. The prize can be found at 4444 Forty-fourth Street, New York, and Alice’s adventure there, which she undertakes with her imaginary friend, a version of the White Rabbit, and a Mad-Hatter styled character named Robin, sees her traversing stereotypical New York sights such as the subway, Park Avenue, China Town, and the Statue of Liberty.

Goldberg’s Alice is a young African-American girl. She wears gold hoops in her ears, and is dressed in a pink T-shirt and jeans, clothes which reflect her ‘real girl’ persona. Alice’s hair is dark and wavy, and pinned back off her face. Her skin is brown and so are her eyes. The reader knows Goldberg’s Alice is African-American because the illustrations tell us so; race does not influence the story. While Goldberg’s motivations to recreate Alice as an African American girl can only be assumed (possibly her own background), her film work around the time when Alice was published demonstrates a record of being involved with films which aim to create a dialogue around ideas of diversity, particularly with regard to race in America.1 Although these films deal with race in more overt ways than Alice, a similar level of social consciousness can be detected in the way Alice’s racial identity is not highlighted. In a discussion of racial privilege and disadvantage, Ramsey (2004, p. 71) emphasizes that ‘Whiteness is the “invisible norm” that sets the standards for everyone else’s experience’. It is a socially constructed standard which is similarly described by Green, Sonn, and Matsebula: ‘White people do not experience the world through an awareness of racial identity or cultural distinctiveness, but rather experience whiteness and white cultural practices as normative, natural, and universal, therefore invisible’ (2007, p. 396). [End of Page 14]

By recreating Alice as an African American child, set within an everyday experience (albeit with nonsensical elements), and producing a story where this child just is, rather than being made a historical, political, or racially stereotyped figure, Goldberg is challenging this invisible norm of Whiteness. Within the multicultural classroom, this kind of challenge benefits all children, including those who identify as being part of mainstream culture. For students of color, the inclusion of literature where they can see themselves reflected in the characters halts the marginalization of their lived experience. And for mainstream students, it removes their ‘false sense of superiority’ (Banks & Banks, 2010, p. 234), and enhances social equity within the school, an essential characteristic of democratic institutions (Gutmann, 2004).

As previously identified, Alice does not follow Carroll’s original plot, but rather takes familiar elements to create a new story. However this Alice knows where she is headed, and a conscious decision is made to go to the ‘Wonderland’ of New York, although as a place, it is as unfamiliar as the original Wonderland. New York’s buildings are described as ‘being so tall they seemed to bend over their heads’, and the streets are full of people and taxis (Goldberg, 1993, p. 12). Although New York is a real city, the potentially fantastical elements are embellished in order to better connect with Wonderland’s nonsensical narrative. Alice’s ride on the subway is described as ‘like nothing else in the world; full of different kinds of people, and graffiti colors that become kaleidoscopic when the train is moving quickly’ (Goldberg, 1993, p. 20). One of Alice’s key experiences in Carroll’s original story is her physical transformations, and this is referenced in Alice to describe a claustrophobic encounter Alice has in a diner. The building shrinks to the size of a ‘Roach Motel’, and the customers surrounding Alice and her companions get bigger and ‘stretchier’ as they move in closer, chanting about Alice in unison (Goldberg, 1993, p. 18). This transformation is a new idea and positions Alice even more firmly than in Carroll’s Wonderland, as the totem of normality in this fantastical world.

What Alice (1993) does with Carroll’s Wonderland is recreate the story in a contemporary setting, in a real place, with a new Alice. Goldberg’s Alice shares some of the personality traits exhibited by Carroll’s Alice – a sense of adventure, courage, and an ability to adapt to different situations – and these shared traits are important when it comes [End of Page 15] to adapting a character as well-known as Alice, in a way she has never been seen before. Through using characteristics which make Alice seem universal, it is easier to see how Alice can indeed be any girl. In a discussion on making literature meaningful within the classroom, Morley and Russell (1995, p. 261) describe how ‘the cultures explored in certain books may be foreign to [some] children, but the common bonds of humanity are very evident’. Alice’s adventure crosses time and cultural boundaries, as evidenced by its continued publication around the world, and one of the reasons for its continued popularity is the chord Alice strikes with young readers.

Nancy Sheppard and Donna Leslie’s Alitji in Dreamland

Alitji in Dreamland was first published in 1975, and reprinted to coincide with the 125th anniversary of the publication of Carroll’s story. Written by Nancy Sheppard and illustrated by Donna Leslie, it is a more unusual adaptation because the story is told in English, but has also been translated by Sheppard into Pitjantjatjara, a language spoken by Indigenous communities living in Central Australia, which includes South Australia and parts of the Northern Territory.

Figure 4. Front cover of Alitji in Dreamland by Nancy Sheppard and Donna Leslie.

The Wonderland in Alitji in Dreamland is created with references to Australian flora and fauna, with most characters re-written to reflect Australian culture. Two of the clearest examples of this are the White Rabbit who has become a White Kangaroo carrying a dilly-bag and a digging-stick, and the Caterpillar, who is now a Witchety Grub. Despite these factual references, Alitji’s adventure still takes place in a Wonderland, entered by following the White Kangaroo down a hole, and emerging at the end by awakening from a dream. Alitji comments at one point ‘how [End of Page 16] pleasant it was in my own country’, emphasizing for the reader that the land she is currently moving through is not her reality. Colors found in the natural world are used for the illustrations, with an emphasis on reds, oranges, and yellows. These colors reflect traditional Aboriginal art, and the connection Aboriginal Australians have with the land.

In Sheppard’s book, Alice has been renamed Alitji, and she is a young, Aboriginal Australian girl. Her skin is brown, her hair is black, and decorated with berries, which Alitji wove through her strands to help alleviate some of her boredom from listening to her sister tell a story – an alternative to Carroll’s Alice considering whether to get up and make a daisy-chain. Alitji does not wear clothes or shoes, and neither do other Indigenous characters who appear in the story. Similar to the African Wonderland of Taylor’s story, Sheppard’s Australian Wonderland is set in postcolonial times, and the adaptation of the Hatter and March Hare’s Tea Party is used to highlight the racial tension and conflict which arise when two opposing cultures clash. The Hatter and Hare become a Horse and Stockman, and in an interpretation of the previously mentioned comment by the Hatter, advising Alice her hair wants cutting, the Stockman tells Alitji, ‘Your skin is very dark. You ought to wash yourself’. Alitji responds, as described by Sheppard, ‘with dignity’, by saying, ‘My skin is always dark, even after washing’ (Sheppard 1992, p. 63). This is an impressive adaptation of the Tea Party scene, which speaks not only to the historical marginalized Indigenous Australian experience, but can also be taken as a commentary on the historical White-washing of children’s literary characters.

Dreamland (1992) closely follows Carroll’s narrative, including each scene and character in the order in which they appear in Wonderland. However, as explained by Minslow (2009, p. 220), ‘Sheppard has transformed the Victorian dress, housing, kinship, and connections to the natural environment to better reflect what she conceptualizes as those specific to Aboriginal culture and society’. In place of Alice listening to her sister read while sitting on a riverbank, Alitji is sitting in a creek-bed with her sister, and they are playing a story-telling game. This shift is an example of Carroll’s story being altered to reflect a new cultural characteristic – the significance of oral storytelling in Aboriginal culture. The essence of the scene remains, while being sympathetic to its new readership. Shavit (2009, p. 115) describes this occurring when ‘the model of the original text does not exist in the target system, [then] the text is changed by deleting or by adding such elements [End of Page 17] as will adjust it to the integrating model of the target system’. This clearly occurs with the translation of the story into the Pitjantjatjara language, but also in the translation of objects and places which reflect changes in the childhood experience from Victorian England, to contemporary Australia.

Much has been written about Wonderland’s contemporary references to, and parodies of, social mores, expectations of childhood, public figures, and previous literature (Cohen, 1995; Empson, 1935; Gardner, 2001; Haughton, 2003; Susina, 2011). In order to amuse nineteenth- century children, Carroll needed to create connections throughout the narrative which they could personally relate to. This is why some aspects of the story may be problematic for twenty-first century children. These in-jokes, references, and witticisms all work to establish a community between Carroll, his readers, and the story, where membership can only be gained through embarking on the adventure laid out within the pages of the book. As discussed by William Myers (2014) ‘books transmit values. They explore our common humanity’. Carroll did well enough to balance contemporary references for his then audience, with timeless references so the story can still be enjoyed 150 years later; however, this concept of creating an intimate community is also clear in Dreamland.

The Australian and Aboriginal Australian references throughout Dreamland work to fashion the land in which Alitji experiences her adventure, but by doing so, it also fashions a particular readership, who all share a particular knowledge and awareness. A shared knowledge and awareness is significant for this particular community of child readers, as they are largely absent from mainstream children’s literature. William Myers (2014) questions what the message is when some children are not represented in children’s books. Aboriginal Australian children belong to one of the oldest cultures in the world, yet are also a part of one of the most marginalized within their own country: a result of the ‘decimation of Aboriginal populations, [and] destruction of Aboriginal culture’, following the British colonization of Australia (Purdie, Dudgeon & Walker, 2010, p. 5). This marginalization has manifested in high rates of unemployment, lower average income, high rates of arrest and imprisonment, poor health, low education and low life expectancy – all indicators of the consequences of entrenched institutionalized racism (Dudgeon et al., cited in Purdie, Dudgeon & Walker, 2010, p. 22). Aboriginal Australians are largely [End of Page 18] invisible in public life, with the exception of negative stereotyped images which result in further marginalization. What Dreamland does is put Indigenous culture at the forefront of Wonderland by employing elements of Indigenous culture within a traditional setting, and using traditional language, to retell a familiar English story.

The meticulous changes to characters, place, and language throughout the narrative indicate the intended audience for Dreamland was Aboriginal Australian children. This differs from Taylor’s (2012) adaptation, where the impression is created that it was written for children for whom Africa is a foreign place. The language of Dreamland assumes knowledge, rather than provides instruction, and is not simply a translation of Carroll’s story into another language, but an example of the story being appropriated for a new culture. Wilson (1992, pp. 101-102) identifies Dreamland as the forty-fourth language translation of Wonderland, and describes how this adaptation demonstrates the ‘universality of Lewis Carroll’s imagination’. By making Wonderland culturally relevant for a new audience, Dreamland creates a sense of inclusion for children who can culturally now relate to Alice’s adventure, while simultaneously revealing how flexible all aspects of the narrative are, written and visual.

Conclusion

This paper goes some way to exploring how the uniform presentation of Alice across literary adaptations is at odds with the flexibility of the story, and what this can mean for Wonderland’s culturally diverse child readers. In his book Ways of Seeing (1972), Berger describes how seeing comes before words. Referring to childhood, Berger goes on to state that ‘the child looks and recognizes before it can speak’ (1972: 7). This ability to absorb information using visual cues taps into the idea that the hegemonic aspects of a culture are established by what and who is most visible. There is a clear connection here with racial diversity, discussed by Ramsey (2004, p. 81), exploring how children ‘absorb prevailing attitudes about race as they grow up. By the preschool years, children begin to express stereotypes of groups’. Diversity, and its acceptance or rejection, are part of the socially constructed experience of childhood, therefore the learned outcome will depend on what the child is exposed to, at home and in the classroom. [End of Page 19]

Harris (1995, p. 276) states that ‘books are powerful. They can serve as catalysts for the greater good or they can bolster the tyranny of a few’. It is a sentiment similarly expressed by Swadener, Dunlap, and Nespeca: ‘[Literacy] has overt sociopolitical meanings and functions and has been used to define, exclude, oppress, and alienate, as well as to clarify, include, empower, and connect children and families to their community’ (1995, p. 267). The power of Wonderland lies with its universality, but its potential is not being embraced by adapters. Wonderland offers opportunities to encourage cultural and language diversity through the racial representation of Alice, and act as an effective tool in multicultural classrooms by showing a familiar story in new ways. Purdie, Dudgeon, & Walker (2010, p. 17) highlight how developmental psychology and social learning theory show there are ‘mechanisms by which children acquire the particular stereotypes of their culture’. The examples the authors provide involve both direct instruction, ‘that particular racial groups are “dirty” or “can’t be trusted”’ and ‘unconscious inferences’ generated from observing the behavior and attitudes exhibited around them (Purdie, Dudgeon & Walker 2010, p. 17). How these mechanisms can be immobilized is outlined by García Coll, and Vázquez García (cited in García Coll, Lamberty, Jenkins, McAdoo, Crnie, Wasik. & Vázquez García 1996, p. 1899), who state that if: that certain environmental conditions and socialization patterns, such as de-emphasizing in-group/out-group distinctions, providing positive models, and reducing social distance, can contribute to reducing the development of prejudicial attitudes in children.

Particularly key for this paper is the emphasis by García Coll et al. (1996) on positive, integrative models, as this involves what a child can see, and therefore establish connections with. These positive models of racial diversity are missing in conventional adaptations of Wonderland. The 150th anniversary of Wonderland’s publication occurs in 2015, and the hype surrounding Carroll’s story will be widespread. This anniversary creates a vehicle for adapters and teachers to showcase Wonderland, and demonstrate why this story has endured when many others have not. There is also an opportunity to play with the potential for racial diversity by using illustrated representations of Alice such as those introduced here in the classroom. There is nothing wrong with the thousands of White Alices who are already a part of the global world of Wonderland adaptations, but [End of Page 20] why not expand on the creativity and flexibility Wonderland offers, and give child readers a new face to look at. [End of Page 21]

Notes

- The Color Purple (1985), The Long Walk Home (1990), Sarafina! (1992), Made in America (1993), Corrina, Corrina (1994), The Associate (1996), Cinderella (1997 – an adaptation with an African American Cinderella), Our Friend Martin (1999).

Bibliography

Primary texts

Carroll, L. (2003 [1865]). Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. J. Tenniel (illus.). London: Penguin Books.

Goldberg, W. (1993). Alice. J. Rocco (illus.). London: Pavilion Books.

Sheppard, N. (1992). Alitji in Dreamland: Alitjinya Ngura Tjukurmankuntjala. D. Leslie (illus.). East Roseville: Simon & Schuster.

Taylor, E. (2012). Alice’s Wonderful Adventures in Africa, http://erintaylorillustrator.com/about/ and http://alicesadventuresinafrica.blogspot.de

Secondary texts

Banks, J. A. (2010). Approaches to multicultural curriculum reform. In J. A. Banks & C. A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives (7th ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 233-256.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books.

Boutte, G. S., Hopkins, R. & Waklatsi, T. (2008). Perspectives, voices, and worldviews in frequently read children’s books. Early Education and Development, 19(6), 941-962.

Cooperative Children’s Book Centre. (2014). Children’s Books by and about People of Color Published in the United States. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved from http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp.

Cohen, M. (1995). Lewis Carroll: A Biography. New York: Random House.

Empson, W. (1935). Some Versions of Pastoral. London: Chatto & Windus.

Galda, L. & Cullinan, B. E. (2002). Literature and the Child (5th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. [End of Page 22]

García Coll, C., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., McAdoo, H. P., Crnie, K., Wasik, B. H. & Vázquez García, H. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891-1914.

Gardner, M. (2001). The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition. London: Penguin Books.

Goodman, J. & Melcher, K. (1984). Culture at a distance: An anthroliterary approach to cross-cultural education. Journal of Reading, 28(3), 200-207.

Green, M. J., Sonn, C. C. & Matsebula, J. (2007). Reviewing Whiteness: Theory, research, and possibilities. South African Journal of Psychology, 37(3), 389-419.

Gutmann, A. (2004). Unity and diversity in democratic multicultural education: Creative and destructive tensions. In J.A. Banks (Ed.), Diversity and Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 71-96.

Harris, V. J. (1995). Afterword: ‘May I Read This Book?’ Controversies, dilemmas, and delights in Children’s Literature. In S. Lehr (Ed.), Battling Dragons: Issues and Controversy in Children’s Literature. Portsmouth: Heinemann Publishing, pp. 275-284.

Haughton, H. (2003). Notes to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. London: Penguin Books.

Hefflin, B. R. & Barksdale-Ladd, M. A. (2001). African American children’s literature that helps students find themselves: Selection guidelines for Grades K-3. The Reading Teacher. 54(8), 810-819.

Hughes-Hassell, S., Barkley, H. A & Koehler, E. (2009). Promoting equity in children’s literacy instruction: Using a Critical Race Theory framework to examine transitional books. School Library Media Research, 12. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/aaslpubsandjournals/slr/vol12/SLMR_PromotingEquity_V12.pdf

Hutcheon, L. & O’Flynn, S. (2013). A Theory of Adaptation (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Jaques, Z. & Giddens, E. (2013). Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass: A Publishing History. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

Kymlicka, W. (2012). Multiculturalism: Success, Failure and the Future. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute/Transatlantic Council on Migration. Retrieved from http://www.upf.edu/dcpis/_pdf/2011-2012/forum/kymlicka.pdf [End of Page 23]

Manning, M. L. & Baruth, L. G. (2004). Multicultural Education of Children and Adolescents (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education.

Marshall, E. Z. (2007). Liminal Anansi: Symbol of order and chaos. An exploration of Anansi’s roots amongst the Asante of Ghana. Caribbean Quarterly, 53(3), 30-40.

Meier, T. (2003). ‘Why Can’t She Remember That?’ The importance of storybook reading in multilingual, multicultural classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 57(3), 242-252.

Minslow, S. G. (2009). Can Children’s Literature Be Non-Colonising? A Dialogic Approach to Nonsense. (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). The University of Newcastle, Newcastle.

Morley, J. A. & Russell, S. E. (1995). Making literature meaningful: A classroom/library partnership. In S. Lehr (Ed.), Battling Dragons: Issues and Controversy in Children’s Literature. Portsmouth: Heinemann Publishing, pp. 253-271.

Myers, C. (2014, March 15). The apartheid of Children’s Literature. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/opinion/sunday/the-apartheid-of-childrens-literature.html.

Myers, W. D. (2014, March 15). Where are the people of color in children’s books? The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/opinion/sunday/where-are-the-people-of-color-in-childrens-books.html?_r=0

Pinto, C. F. (2009). The animal trickster – an essential character in African tales. In K. Kumpulainen and A. Toom (Eds.), The Proceedings of the 19th Annual Conference of the European Teacher Education Network. Helsinki: European Teacher Education Network, pp. 99-109. Retrieved from http://www.eten-online.org/modules/newbb/dl_attachment.php?attachid=1266750631&post_id=211

Pirofski, K. I. (2001). Multicultural literature and the children’s literary canon. Critical Multicultural Pavilion, EdChange Project. Retrieved from http://www.edchange.org/multicultural/papers/literature.html

Purdie, N., Dudgeon, P. & Walker, R. (2010). Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice. Commonwealth of Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research, the Kulunga Research Network, and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research. Retrieved from http://aboriginal.telethonkids.org.au/media/54847/working_together_full_book.pdf. [End of Page 24]

Ramsey, P.G. (2004). Teaching and Learning in a Diverse World (3rd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

Robles de Meléndez, W. & Beck, V. (2013). Teaching Young Children in Multicultural Classrooms: Issues, Concepts, and Strategies (4th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Shavit, Z. (2009). Poetics of Children’s Literature. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Sipe, L. R. (2012). Revisiting the relationships between text and pictures. Children’s Literature in Education, 43(1), 4-21.

Susina, J. (2011). The Place of Lewis Carroll in Children’s Literature. New York: Routledge.

Swadener, B. B., Dunlap, S. K. & Nespeca, S. M. (1996). Family Literacy and Social Policy: Parent perspectives and policy implications. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 11(3), 267-283.

Wilson, B. K. (1992). Notes to Alitji. In N. Sheppard, Alitji in Dreamland: Alitjinya Ngura Tjukurmankuntjala. East Roseville: Simon & Schuster, pp. 101-103. [End of Page 25]