| Integrating Environmental Awareness in ELT Through Picturebooks

Ana Cecilia Cad, Susana Liruso and Pablo E. Requena |

Download PDF |

Abstract

This paper provides a report of classroom experiences that provide insight into the use of a picturebook to raise students’ environmental awareness in an ELT primary context in Argentina. It describes how a picturebook can help build reading comprehension in a second language and foster learning across the curriculum mediated by literature. First, we discuss how picturebooks can contribute to ELT and to raising students’ awareness of environmental citizenship. Then, we present two pedagogical interventions with children aged 9 to 11 years old that made use of a teacher-produced picturebook dealing with the environmental issue of wildfire devastation. Through examples of children’s performance in activities that accompanied the reading events, we illustrate how children can make use of non-linguistic resources to understand linguistic input in a second/foreign language and interpret the meaning of a story. The experiences also reveal a teacher-initiated approach to facilitate reflection about environmental issues through picturebooks.

Keywords: picturebook, environmental citizenship, pedagogical experiences, ELT, materials

Ana Cecilia Cad is a teacher of English as a foreign language. She holds an MA in Applied Linguistics from the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. She currently teaches at the School of Language, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina and in teacher education at a tertiary institution in Córdoba, Argentina.

Susana Liruso holds an MA in Applied Linguistics and TESOL from King’s College, London University. At present she lectures at postgraduate level at the School of Languages, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. She has been directly involved in language teacher education for 30 years.

Pablo E. Requena is a teacher of English as a foreign language. He received an MA in Spanish and a Ph.D. in Spanish Linguistics and Language Science from Penn State University. He currently teaches at the University of Texas in San Antonio, USA.

Introduction

Historically, pictures have been used in young children’s books to provide enjoyment as well as to aid in the development of literacy and in the process of learning content subjects. Still, one particular format has proven versatile in the exploitation of multimodal material (text and images) across the curriculum: the picturebook. Of particular importance are picturebooks that not only use both pictures and words to create meaning, but also offer an innovative and enriching experience through timely topics that are of great importance in elementary education (Bintz, 2011). In ELT, picturebooks help contextualize words, expressions and concepts and foster a thinking response in the target language, English (Mourão, 2016). Therefore, picturebooks are ideal second/foreign language teaching and learning tools that can approach local as well as global concerns, such as environmental preservation.

The world is experiencing an environmental crisis that impacts both global and local ecosystems. Environmental citizenship education could play a role in improving or maintaining environmental quality. As a consequence, educational programmes are introducing topics to develop awareness and sensitivity towards these issues. For example, educational guidelines in Argentina (the context where the experiences described in this contribution take place) align with the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 proposed by UNESCO and the National Law of Integral Environmental Education (27.621), which include respect towards biodiversity, active citizen participation, value education, and care for the environment and preservation as key components that promote environmental citizenship.

The present study describes two pedagogical interventions with Argentinian elementary students of English as a foreign language using a teacher-made picturebook that addresses the environmental issue of fire devastation. Through a depiction of the pedagogical strategies and student productions, this contribution thus illustrates how a teacher-generated picturebook can be used to approach a pressing issue while promoting meaningful language teaching and learning experiences in the ELT classroom.

Picturebooks and ELT

Despite individual differences, children are capable of processing and integrating more than one mode of communication at a time (Xiao et al., 2002) and picturebooks can create a unique visual and linguistic experience. Through multiple modes of communication, these artifacts guide reading comprehension, which increases their pedagogical potential (Arizpe & Styles, 2015; Serafini, 2014). Research on primary school children’s responses to picturebooks reports that even children who are very young or not fluent in English as a second language are able to make sense of and infer information from fairly complex multimodal material (Arizpe & Styles, 2002). Such a holistic approach that uses linguistic and visual (pictorial) information can make a narration more accessible to students, increasing their involvement with the material and engaging their emotions as a result of story comprehension (Reyes-Torres et al., 2020).

Picturebooks have other merits and advantages that attract foreign language teachers. They provide a literary experience, and an appreciation of literature across the curriculum is encouraged by official documents in Argentina (NAP, 2005). Several scholars agree that picturebooks are literary forms that contain pictures, written language and design elements as interconnected features (Nikolajeva, 2010; Scott, 2010; Serafini & Reid, 2022). Picturebooks have always carried images with strong connotations that call upon metaphoric construction (Chaves, 2013). These aspects of design become particularly meaningful when young learners cannot interpret words and have to rely on other semiotic cues to understand the plot of the story. Besides, the multiplicity of non-verbal resources can help children establish meaningful connections between design elements and words.

In a nutshell, picturebooks can play an important role in fostering second/foreign language acquisition thanks to the ways in which written language and design elements interconnect (Nikolajeva, 2010; Scott, 2010; Serafini & Reid, 2022). These artifacts constitute powerful tools to promote comprehension in ELT.

Environmental Citizenship

There is nowadays ‘a reconceptualization of language education as an important contributor to a number of educational missions’ (Byram & Wagner, 2018, p. 149). Among those missions, promoting citizenship stands out since it is vital to the success of life in society. Environmental citizenship refers to citizens’ respectful behaviour towards the environment that sparks from the belief that there should be a fair distribution of environmental goods and that people should engage in the development of sustainability policy. In other words, this definition stresses the relevance of citizens’ active participation in building a sustainable future (Dobson, 2010). Promoting environmental citizenship is an important aspect to explore environmental problems at a local and global scale, and to foster civic engagement among students.

There is a strong connection between early environmental education and young learners’ willingness to engage in activities that promote pro-environmental values and encourage them to adopt a hands-on approach to tackling environmental issues (Ampuero et al., 2015). Young students tend to show more willingness to participate in individual and collective actions (such as those called for in the systematic instruction of Environmental Citizenship) that may positively contribute to their community (Činčera et al., 2020). To promote successful student engagement in environmental education, Kyburz-Graber (2013) proposes that educational approaches should be: a) participatory: activities should foster collaboration and engagement; b) constructive: students should participate in the construction of meaning and solutions; c) critical: the task should favour questioning social reality and d) reflective: activities that promote the reflection on causes and consequences of different issues and their potential solutions.

Different educational initiatives around the world are actively pursuing environmental citizenship. For example, in 2018 The European Network for Environmental Citizenship (ENEC) defined ‘Education for Environmental Citizenship’ (EEC) as

the type of education which cultivates a coherent and adequate body of knowledge as well as the necessary skills, values, attitudes and competences that an environmental citizen should be equipped with in order to be able to act and participate in society as an agent of change in the private and public sphere, on a local, national and global scale, through individual and collective actions, in the direction of solving contemporary environmental problems, preventing the creation of new environmental problems, in achieving sustainability as well as developing a healthy relationship with nature (ENEC, 2018).

One of the working groups within the ENEC mentions ‘Identification of good examples and best practices that lead to environmental citizenship in primary formal education’ as one of their objectives. Examples of efforts in the European context abound. For instance, Monte and Reis (2021) offer a Pedagogical Model of Education for Environmental Citizenship in primary education. One of the several main objectives includes recognizing and identifying the consequences of environmental changes such as wildfires. Many similar programmes and efforts are also being pursued in the Americas. For instance, in 2011 the US Department of Education created the Green Ribbon Schools (ED-GRS) recognition award to promote, among other things, ‘effective sustainability education, including robust environmental education that engages STEM, civic skills and green career pathways’ (Green Strides, n.d.). Particular programmes and initiatives are being developed by individual states, districts, and schools, such as an environmental citizenship programme at The Nueva School in California (The New School, n.d.).

Similar programmes have been developed in Australia through the document entitled Educating for a Sustainable Future: A National Environmental Education Statement for Australian Schools (2005). This document states the purpose of environmental education and explains its implementation in Australian schools. It specifies the roles of teachers, schools, their communities and the education. Other programmes launched by the Australian government have been Living Sustainably: The Australian Government’s National Action Plan for Education for Sustainability (2009) and, the Sustainability Curriculum Framework (2010). These plans aimed at providing Australians with knowledge and skills to live sustainably (GEEP, n.d.).

In Latin America, in the early 2000s, local governments implemented projects that were articulated with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and supported the Latin American Global Environmental Citizenship Project. Similar initiatives were launched by the Peruvian Ministry of Environment’s 2009 Environmental Citizenship Prize, Brazil’s Secretariat of Institutional Articulation and Environmental Citizenship and Chile’s Youth National Environmental Citizenship Day (Latta & Wittman, 2010). In 2019, Argentina manifested its increasing ambition to address environmental literacy and citizenship through its national law (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, n.d.).

In Argentina, where the experiences described in this paper took place, official documents (NAP, 2005) recommend for primary education to treat subjects in an interdisciplinary way under the umbrella of citizenship. Accordingly, citizenship is approached across disciplines like social studies, natural sciences and language in articulated ways. The topic of fires is particularly important because during dry seasons, Argentina experiences significant fire events that can have devastating effects on people, animals, trees and houses. There are fire protection laws and there is also a fire prevention tax since the province is financially responsible for the prevention and extinction of wildfires. It is a concern deeply rooted in the local community, therefore efforts should be made to make children aware of the damage and to educate them to prevent wildfires in the region.

Considering the great diversity of topics that picturebooks can bring into the primary classroom, they can be used across a wide range of curriculum areas (Hsaio, 2010; Pantaleo, 2008). Given such potential for addressing environmental citizenship, we describe in this paper two experiences in which a picturebook was employed to deal with an environmental issue and English as a second language to primary school students in Argentina. We will first discuss the picturebook and then share the classroom experiences in which students further developed their reading in the foreign language by interpreting both the visual and verbal semiotic resources, and engaged in awareness by being part of activities that promoted collaboration among peers, construction of meaning, questioning and reflection.

Environmental Citizenship through Picturebooks: The Picturebook Fear, force, _____

The reading material used for the experiences was a picturebook called Fear, force, ____ (Liruso, 2022, see picturebook in PDF format https://bit.ly/3E7ikQZ. This compact, teacher-produced book has the basic elements of a fictional narrative – characters, setting and event – and as such can be considered a story (Narančić Kovač, 2021). Chatman (1978) states that all narratives share the same basic structure: the elements of the storyworld – characters, events, happenings and setting – and that the story is told by a narrative discourse. The main character of the story is a red and orange giant that metaphorically represents fire. In the story, it is possible to see how the giant walks around the forest creating destruction in its wake. Op de Beeck (2018) establishes that picturebooks can be recognized by their material characteristics. Liruso’s work can be recognized by its handheld format, limited pages and few words and pictures per page and spread. Besides, the sequence displayed page-to-page presents interdependent meaning cues that enable the reader to understand the potential destruction that fire may cause around forests.

Liruso’s work is an 8-page narration in which pictures and images intertwine in a symbiotic relationship to create meaning. The reader needs to rely on the interpretation of the pictures to fully understand the meaning of the text. For example, the meaning realization of the word giant is constrained by its illustration that leads the reader to interpret the word as fire. In picturebooks, imagery plays an important role in the understanding of the message, as it can clarify, complement, enhance, or even contradict the meaning of the verbal text (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006; Nodelman, 1988). For Mourão (2012), this interdependence ranges along a continuum from a simple showing and telling of the same information to a more complex showing and telling of different, even contradictory information. Those books that can be located toward the complex end of the picture-word dynamic generate a gap between the meaning conveyed by words and pictures. This gap poses a challenge for ‘young learners to search for, and in the classroom negotiate for, understanding and meaning’ (Bland, 2013, p. 32), providing what Halliwell (1992) calls ‘realistic opportunities for interaction and talk, instinctive in children at this age’ (p. 5).

Image and text relationships

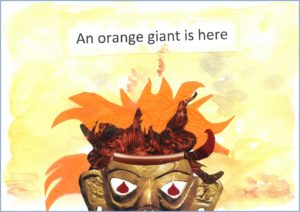

The images of the picturebook were crafted using a collage technique. Additionally, watercolours create the visual environment, the background to the story. In picturebooks, colour can be strategically used to create a particular mood, provide cues to understanding the emotional states of characters, make particular objects or characters stand out, establish connections between characters, objects and/or events (Lewis, 2001; Moebius, 1986; Nodelman, 1988) and contribute to the development of a character, setting or plot (Martinez et al., 2020). The character that stands out is presented on the first page (see Figure 1). The text that accompanies the image reads ‘An orange giant is here’. A colour, orange, and the name of a huge figure, ‘giant’, are used instead of the object fire.

The concept of fire, then, is metaphorically configured both visually and linguistically. The whole metaphor is a personification. Children are familiar with personification since they are used to animals and inanimate objects showing human characteristics in stories and fables (Aesop, La Fontaine).

Figure 1. From Liruso, Susana (2022). Force, Fear, _____.

Presenting fire with this high range of suggestiveness, we believe, indicates the setting and establishes mood in a forceful way. Predominant background colours are red, orange and yellow when the giant is present. The choice of this colour palette conveys the presence of fire in a particular setting. As the sequence of the picturebook advances, pale yellow and different gradations of black and grey are used to convey the destruction and feelings of desolation brought about by forest fires. The main character, a giant, a tongue of fire, and a dust column have been built using different materials like magazine clips and cardboard paper to add extra meaning, colour and texture to the story. The choice of colour and different texture also highlights the presence of the fire and the readers’ attention is easily captivated by this character, which is important to understand in its development in the narrative.

The cover is white with only a red band and an incomplete title. Children need to read the story in order to complete the title. This visual strategy contributes to children’s engagement with the text. The fact that the readers were asked to do something with the title shaped the reading experience because it ignited curiosity. A filling-the-gap activity is very familiar to children learning English and thus enables participation right from reading the cover. In Liruso’s picturebook, the narrative unfolds temporally and spatially. Still, the use of other narrative techniques such as closeups, long shots and bird’s eye views allows the reader to manipulate the pages and its timing (Op de Beeck, 2018). Some of the visual techniques employed by the illustrator involved the use of a close-up to introduce the main character. This technique is particularly useful since the giant stands for fire and, by bringing its picture to the foreground, the readers’ attention is focused on the character and they are more likely to explore the giant’s orange hues and flame-shape hair that, in turn, may contribute to their understanding of the visual metaphor. Besides, as McClintock (2016) points out the size and shape of illustrations is all about creating a sense of time, movement, emotion and place’ (p. 32). Thus, presenting the main character through a close-up, the reader is invited to spend time analysing and interpreting its features while developing an emotional response to the text. Specific details like the image of a big tongue creates a vivid scene. Fear, force, fire is presented at the beginning as a portrait – the enormous head of the fire giant, a powerful image of contact, and moves towards a landscape of a devastated forest with the giant at a distance, an image of offer, to end with the disappearance of fire, just a white empty space that symbolizes devastation.

Focusing the readers’ attention

Different features of the picturebook design were used to focus the children’s attention. Long-shots are used for the reader to focus not only on the giant but also on the dust, ashes and destroyed forest. In addition, close-ups invite the reader to spend time exploring the scene. According to Dowd Lambert (2018), larger pictures create ‘the perception of expanding a given moment in time as it invites the reader to linger on that larger picture’ (p. 29). The design of the illustration and written word in each spread invites the reader to take time to absorb the meaning of the events and actions they are witnessing. The absence of frames also invites the readers into the picture (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2006), which would engage them in connecting cognitively and emotionally with the topic, creating a greater sense of intimacy in the reading.

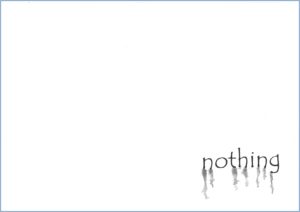

The use of certain fonts against particular backdrops ‘combines to fix the reader’s attention on the single bit of text’ (Dowd Lambert, 2018, p. 33). For instance, at the end of the picturebook, the word nothing is placed against a white background (see Figure 2), which seems to represent the sense of emptiness and void created after a fire causes significant destruction in a community. The place in which the text is located and its typographic features, such as form and size, are important aspects of the layout. Serafini and Clausen (2012) state that ‘the typography of written language not only serves as a conduit of verbal narrative […] it serves as a visual element and semiotic resource with its own meaning potentials’. (p.23) The shape of the word nothing conveys the action of melting and disappearing. In this way, the reader’s attention is focused on the meaning potential of the word ‘nothing’ and prompts other meaning realizations, such as void, destruction and desolation.

Figure 2. From Liruso, Susana (2022). Force, Fear, _____.

Topics reflecting local and global environmental concerns

In terms of topic, as Kümmerling-Meibauer (2018) states, picturebooks are bound to the specific cultural, political, pedagogical and aesthetic conditions of their time. Some titles that cover more challenging topics, or provide opportunities of approaching topics from a different perspective, are suitable for older primary learners and encourage a more active role on the part of the learner, who is capable of making sense of the words they read and the pictures they see. Picturebooks reflect the times as well as their author’s and illustrator’s cultures. Liruso’s picturebook conveys current environmental concerns about local forest fires. Even when the book responded to the need of a specific reality of a community, the message conveyed is universal. The decision to write the story comes from the need to work with materials that suit the local context but it is not restricted to it. As Op de Beeck (2018) states ‘childhood is a period of first encounters with cultural information’ (p. 23). This material could pave the way to deal with the topic of bushfires in a transdisciplinary fashion, such as in English and instruction in the Natural Sciences. Environmental issues are a topic of the Argentinian curricula and receive particular attention during the dry season in this and other areas of the country.

Environmental Citizenship through Picturebooks: Two ELT Classroom Experiences

Within the ELT content, picturebooks provide students with meaningful input and promote language use through the learners’ interpretation of the picturebooks, words and design. These books can provide authentic opportunities for learners to interpret the verbal and visual texts and respond to them in English. In the description of our experiences, there will be an emphasis on how visual as well as verbal texts were employed to promote language development by prompting learners’ responses to a text.

Experience N° 1

Context. This experience took place in a fifth-grade classroom of a semi-private school where students (ages 9-10) have one 40-minute class period of English as a second language every week. They had received this exposure for three years. An estimation from observation and information from the course teacher suggested the general language level was A2 according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001), however probably lower in L2 production. The students speak Spanish as a native language. The two researchers were in charge of telling the story and carrying out the activities. Neither of them were the teachers of the course. One was the author-illustrator of the picturebook.

Experience. One of the researchers conducted the lessons while the other researcher took down field notes, recorded student exchanges during group work discussions and also took photographs of students’ productions. The researcher in charge of note-taking, the observer, was present throughout the class intervention and took on a more active role on only two occasions when children turned to her to ask for words in English.

Before the students began to read the story, some key vocabulary (e.g., fear, heat, go away) was explicitly taught by means of pictures to allow learners to incorporate vocabulary that would help them talk about the story using English. This also paved the way for the interpretation of figurative language, (e.g., tongue of fire). Then a copy of the picturebook was handed over to pairs of students to read on their own. They were instructed to read the story and complete the blank of the title with one word. As students read the story, the teacher of the course as well as the researchers walked around the classroom and observed how the students made meaning of what they read, relying on picture interpretation when they were not sure of the meanings conveyed by words. Students worked collaboratively in the interpretation of the story as the members of the pairs tried to interpret the gaps created between words and pictures. From the information collected by the observer, as she listened to the negotiation between pairs of readers, it was noticeable that students’ interpretations were heavily influenced by the specific colours in the picturebook. Colours like red, orange and yellow were clearly associated with fire.

The shape and texture of the illustration of dust made it simple for students to understand the expression ‘vomit dust’. The different degrees of grey might have contributed to the understanding of concepts like ‘nothing’, which is what is left after a fire, since children pointed to the fact that there were no trees and no grass. The white background also contributed to creating a sense of emptiness since there was no imagery that guided interpretation. Some students turned to the observer to ask: ‘What happened here?’. Through different questions like ‘What happens when there is a fire in the forest?’, the observer could guide the interpretation of the students. Once the reading concluded, the following questions to check the general understanding of the text were asked: ‘How did you complete the title?’, ‘What’s the story about?’, ‘Why do we call it giant?’. Time was taken to discuss the metaphorical meaning of the picture and the word ‘giant’. Some interpretations pointed to the fact that the metaphorical character (see Figure 1) seems to have ‘fire in the eyes’, that it ‘looks angry’ and the discussion continued in English and in Spanish as children explained that ‘somebody furious, angry can cause damage’. They also said that a ‘giant’ smashes everything, cannot be stopped and is very strong.

Further questions stimulated students to summarize the story. Understanding the ending is important, and there are clear clues: the scene moves from a bright palette of red and orange to a greyish colour and finally ends in an empty page with the word ‘nothing’. The most important questions were: ‘Can you describe what happens?’, ‘What happens when the giant goes away?’, ‘How do you feel?’. As was stated, students were able to answer the questions using simple sentences and Spanish in some instances, which were later repeated in English by the researcher in charge of carrying out the experience. By answering these questions, students could develop a reflective eye to start making sense of a reality that is part of the context where they live.

In this way, the story laid the ground for the discussion of the global environmental issue of fires in their local context. Students brought up the topic of the wind extending fires, the destruction of plants and the toxic smell and powder of ash that can be experienced in their city and is dramatically illustrated in the picturebook. They produced instances of language such as this ‘It is very sad to see black trees, all quemados (burnt)’, ‘the air is very toxic and bad for people’, ‘when it’s seco (dry) fires in the hills are dangerous’.

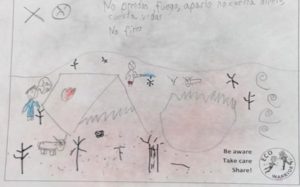

After that, a map of Argentina was shown and students were asked to identify the areas of the country in which fires tend to occur with more frequency and have the most devastating results. Students were able to identify the areas – but had they not known, this could have been the stepping stone for a web search on the occurrence of fires in Argentina in the last five years. In this particular case it was not necessary since students were very aware, especially of the forest fires in their region and in the north-eastern region that was declared an ecological and environmental disaster zone. By exploring their local reality and tapping into students’ feelings and emotions, it is possible to convincingly show how important it is to take action to revert current environmental crises. Students took the role of eco-warriors and thought about possible actions that could work as potential solutions to forest fires. Then, students created posters (see Figure 3) to share their ideas about the actions all children from their school could take to be part of a solution within their communities. By crafting these posters, students could reflect on the causes and consequences of forest fires, and on the ways in which they could become part of the solution. This accords with the concept of active citizenship as discussed earlier (see Ampuero et al., 2015). The example of students’ work in Figure 2 shows not only traces of the picturebook design as the student attempted to recreate the defused colour of the background, and the burnt tress in pitch black, but also – by means of a cross and an angry face and words in both Spanish and English – an emphasis on the importance of avoiding fires.

Figure 3. A student’s poster.

Experience N° 2

Context. This experience was developed with two groups of sixth graders at a state-run primary school where students (aged 11) follow a schedule of two hours of English as a foreign language every week (in the form of a single 120-minute class period). The previous year they had completed the same schedule. An estimation of the proficiency level of these students was about A2 level according to the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001). Students speak Spanish as a native language. One of the researchers was in charge of reading the story. It was not a regular lesson but a special narration session in the framework of the celebration of World Book Day on 23 April which is an annual event that takes place during a whole week to celebrate books and to promote reading.

Experience. On this occasion, children followed the story listening to the teacher- researcher as they read the images and the text. When they encountered unknown words, in most cases they were able to discover their meaning or infer aspects of their meaning with the help of the illustrations and semantically related words. For example, children did not immediately recognize the word ‘giant’, but by looking at the picture, they said ‘monster’. While these two words do not mean the same, the implication is clear, children understood that ‘giant’ must be somebody to be afraid of, somebody that can cause destruction. In what may be the most popular fairy tale about giants, Jack and the Beanstalk, they can eat humans and need to be escaped from. Therefore, the way giants are typically displayed can lead children to bring the meaning of the word ‘giant’ closer to the meaning of ‘monster’. The same happened with the word ‘tongue’ which is presented as a close-up that practically takes up the whole page. This illustration produced lots of comments (admiration, surprise) among the children, it was clear that it caused an emotional impact. They pointed to their tongue and a few students offered the L1 equivalent.

Some pages of the picturebook contain blanks to fill in. For example, in one instance, the story goes ‘when the fire goes away everything is sad and …’, the page is full of black blotches that children interpreted very well and completed with ‘black’ or even ‘black and grey’. The process observed dovetails with Rosenblatt’s (1982) definition of reading as a two-way transaction between the reader and the text that occurs at a particular time and under particular circumstances. This engagement stirs up memories, activating areas of consciousness for the reader who brings to mind experiences, whatever they may be, ‘of language and of the world’ (p. 268). In so doing, the reader establishes ideas about the current text – either fitting them into his/her existing understanding or revising thinking/comprehension to make way for new ideas and concepts. Besides, it was possible to witness the co-construction of meaning when students attempted to understand new vocabulary by providing synonyms, near synonyms or its equivalent in Spanish.

After reading the story the question, ‘What’s the story about?’, was asked for general comprehension and to foster reflection about the causes and consequences of fire. Students participated saying short sentences or words, using Spanish at times to reconstruct the story. It was a good opportunity to work with metaphoric language. From the sentence ‘The wind is its friend’ referring to the fire, children were asked to explain why the wind could be taken as a friend. They were able to explain that the wind can extend a fire and provided other examples using the metaphor: ‘Hot weather is its friend’, ‘Dry grass is its friend’, etc.

Following Callow’s (2016) observation that ‘[v]isual literacy not only involves talking about images but also creating them’ (p. 11), using a scene of fire from the picturebook as a generic frame, young learners were invited to create a new story with characters to nest into the big story. The scene chosen (the one where the giant is dancing in the heat) was enlarged and transferred to a cardboard poster and used as the scenery where the action would take place. Children were next provided with magnetic cards with new characters – a girl, boy, dog, horse and fireman – to create a new story within the setting of the fire in the forest. They worked in groups and then told the stories using the cards and the poster. The cards could be moved around the poster as the action unfolded. All the stories created by the children exemplified neglect as the cause of fire (e.g., tossing away a burning cigarette butt outside) and a good action as a way of solving the problem (e.g., calling the firefighters, saving an animal trapped by the fire), as these examples illustrate:

Student A: ‘Dos niños, Kevin y Mila ven un perro very sad y muy quemado. Más allá

había humo… fire! fire! Agarraron su caballo, Walter, y fueron a buscar a los firemen para apagar el fuego. Fire is a monster’.

[Translation: ‘Two children, Kevin and Mila see a dog very sad and burnt. A little farther, there was smoke… fire! fire! They took their horse Walter and went to look for the firemen to put out the fire. Fire is a monster’.]

Student B: ‘A fire in the forest. Un niño y una niña vieron un caballo correr.

Fueron a ver y… Oh… FIRE, an orange and red fire, very big. Llamaron a

los bomberos y cuando vinieron salvaron a un perrito, Black, a little

dog’.

[Translation: ‘A fire in the forest. A boy and a girl saw a horse running. They went to see and… Oh FIRE, an orange and red fire, very big. They called the firemen and when they came they saved a dog, Black, a little dog’.]

Thus, students could reflect on a global topic such as forest fires and transfer this knowledge to refer to their local reality by means of the stories created.

Conclusion

This article describes the use of a teacher-generated picturebook in two ELT classrooms in Argentina. Two interventions sought to promote environmental awareness with emphasis on the issue of wildfires at the same time that they provided opportunities for foreign language learning through an introduction to a picturebook as a literary text in the ELT class. Three conclusions can be drawn from these experiences.

First, the experiences exemplified how the ELT classroom can be a space where young learners can address a pressing issue of our time and of their own experience. Not only is care for the environment a timely topic, but wildfires impact the local community of the participating students every year. Government agencies, education departments and other entities around the world recognize the need to educate the young about environmental citizenship. However, it is not always clear how to implement such recommendations when faced with a lack of resources and materials. The experiences described here in a Latin American context illustrate a type of ‘bottom-up’ effort to implement environmental education in the ELT classroom. Lack of available materials were compensated through a teacher-generated picturebook and carefully crafted activities were designed to elicit reflection and raise awareness.

But beyond environmental citizenship, the experiences also created opportunities for children to communicate about wildfires, acquire new words in the target language, and participate in a literary experience around a picturebook. The narrative exposed children to new vocabulary (e.g., giant) and allowed children to rely on non-linguistic resources to interpret metaphorical language (e.g., the tongue of fire). From a language learning perspective, these experiences contextualized vocabulary acquisition by connecting it to memorable content and to creative production by the children. But work with the picturebook also exposed children to a multimodal literary format. The use of colour in the background of the picturebook helped the students understand when the fire was present and when it left. The combination of font and white background appealed to the students’ emotions and contributed to their understanding of the meaning of ‘nothing’ and ‘destruction’. In this way, through affordances of picturebooks, key words like ‘flames’, ‘fire’, ‘vomit’ not only were understood but evoked emotional reactions, which hopefully contributed to making this experience with a picturebook a long-lasting one.

Contextualized second/foreign language education requires high levels of involvement by teachers. Highly engaged teachers may be agents of change and introduce interdisciplinary connections to address issues that impact students’ lives. This contribution has hopefully illustrated how picturebook creation and exploitation in the ELT classroom can lead to contextualized language instruction while promoting environmental citizenship.

Bibliography

McClintock, Barbara (2016). Emma and Julia Love Ballet. Scholastic.

Liruso, Susana. Force, Fear, _____. (2022) Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1jcbbkTyFt9fDWyzzlWu37qpENQ5FR1m1/view?usp=sharing

References

Ampuero, D. A., Miranda, C., & Goyen, S. (2015). Positive psychology in education for sustainable development at a primary-education institution. Local Environment, 20(7), 745-763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.869199

Arizpe, E. & Styles, M. (2002). ¿Cómo se lee una imagen? El desarrollo de la capacidad visual y la lectura mediante libros ilustrados. Lectura y Vida, 23, 20-29.

Arizpe, E. & Styles, M. (2015). Children reading picturebooks: Interpreting visual texts. Routledge.

Australian Government, Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (2009). Sustainability curriculum framework: A guide for curriculum developers and policy makers. Commonwealth of Australia. https://cpl.asn.au/sites/default/files/journal/Sustainability%20Curriculum-Framework.pdf

Australian Government, Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (2010).

Bintz, W. P. (2011). ‘Way-In’ books encourage exploration in middle grades classrooms. The Middle School Journal, 42(3), 34-45.

Bland, J. (2013). Children’s literature and learner empowerment: Children and teenagers in English language education. Bloomsbury.

Byram, M., & Wagner, M. (2018). Making a difference: Language teaching for intercultural and international dialogue. Foreign Language Annals, 51(1), 140-151. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12319

Callow, J. (2016). Viewing and doing visual literacy using picture books. Practical Literacy: The Early and Primary Years, 21(1), 9-12.

Chatman, S. (1978). Story and discourse. Cornell University Press.

Chaves, M. (2013). La metáfora visual en el álbum infantil ilustrado. Eme, 1, 62-71.

Činčera, J. M., Romero-Ariza, M., Zabic, M., Kalaitzidaki, M., & Díez Bedmar, M. C. (2020). Environmental citizenship in primary formal education. In A. C. Hadjichambis, P. Reis, D. Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, J. Činčera, J. Boeve-de Pauw, N. Gericke, & M.-C. Knippels (Eds.), Conceptualizing environmental citizenship for 21st century education (pp. 163-177). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20249-1_11

Council of Europe (2001). The common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching and assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Dobson, A. (2010). Environmental citizenship and pro-environmental behaviour: Rapid research and evidence review. Sustainable Development Research Network.

Dowd Lambert, M. (2018). Picturebooks and page layout. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 28-37). Routledge.

Global Environmental Education Partnership (GEEP) (n.d.). Australia. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://thegeep.org/learn/countries/australia

Green Strides (n.d.) About. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://greenstrides.org/about

Halliwell, S. (1992). Teaching English in the primary classroom. Longman.

Hsaio, C. (2010). Enhancing children’s artistic and creative thinking and drawing performance through appreciating picture books. Jade, 29(2), 143-152.

Kyburz-Graber, R. (2013). Socioecological approaches to environmental education and research: A paradigmatic response to behavioral change orientations. In R. B. Stevenson, M. Brody, J. Dillon, & A. E. J. Wals (Eds.), International handbook of research on environmental education (pp. 23-32). Routledge.

Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2018). Introduction: Picturebook research as an international and interdisciplinary field. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 1-8). Routledge.

Latta, A., & Wittman, H. (2010). Environment and citizenship in Latin America: A new paradigm for theory and practice. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 89, 107-116.

Lewis, D. (2001). Reading contemporary picturebooks: Picturing text. Routledge.

Martinez, M., Harmon, J., Hillbrun-Arnold, M., & Wilbrun, M. (2020). An investigation of color shifts in picturebooks. Journal of Children’s Literature, 46(1), 9-22.

Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible (n.d.). Educación Ambiental: Ley de Educación Ambiental Integral. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.argentina.gob.ar/ambiente/educacion-ambiental/ley-de-educacion-ambiental

Moebius, W. (1986). Introduction to picture book codes. Word & Image 2(2), 141-158.

Monte, T., & Reis, P. (2021). Design of a pedagogical model of education for environmental citizenship in primary education. Sustainability 13(11), 6000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116000

Mourão, S. (2012). English picturebook illustrations and language development in early years education[Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Aveiro].

Mourão, S. (2016). Picturebooks in the primary EFL classroom: Authentic literature for an authentic response. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 4(1), 25-43.

Narančić Kovač, S. (2021). A semiotic model of the nonnarrative picturebook. In N. Goga, S. H. Iversen, & A. S. Teigland (Eds.), Verbal and visual strategies in nonfiction picturebooks: Theoretical and analytical approaches. Scandinavian University Press. https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215042459-2021-04

NAP (2005) Núcleos de aprendizajes prioritarios. Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología, República Argentina. www.bnm.me.gov.ar/giga1/documentos/EL000972.pdf

Nikolajeva, M. & Scott, C. (2006). How picturebooks work. Routledge.

Nikolajeva, M. (2010). Interpretive codes and implied readers of children’s literature. In T. Colomer, B. Kümmerling-Meibauer & C. Silva-Díaz (Eds.), New directions in picturebook research (pp. 27-40). Routledge.

Nodelman, P. (1988). Words about pictures: The narrative art of children’s picture books. University of Georgia Press.

Op de Beeck, N. (2018) Picture-text relationships in picturebooks. In B. Kümmerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The Routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 19-27). Routledge.

Pantaleo, S. (2008). Exploring student response to contemporary picturebooks. University of Toronto Press.

Reyes-Torres, A., Portalés-Raga, M., & Bonilla-Tramoyeres, P. (2020). Multimodalidad e innovación metodológica en la enseñanza del inglés. El álbum ilustrado como recurso literario y visual para el desarrollo del conocimiento. Revista Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada a la Enseñanza de Lenguas, 14(28), 54-77.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1982). The literary transaction: Evocation and response. Theory into Practice, 21, 268-277.

Scott, C. (2010). Frame-making and frame-breaking in picturebooks. In T. Colomer, B. Kümmerling-Meibauer & C. Silva-Díaz et al. (Eds.), New directions in picturebook research (pp. 101-112). Routledge.

Serafini, F., & Clausen, J. (2012). Considering typography as a semiotic resource in contemporary picturebooks. Journal of Visual Literacy 31(2), 22-38.

Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the visual: An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. Teachers College Press.

Serafini, F., & Reid, S. (2022). Analyzing picturebooks: Semiotic, literary, and artistic frameworks. Visual Communication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14703572211069623

The European Network for Environmental Citizenship (ENEC) (2018). Defining ‘Education for Environmental Citizenship’. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from http://enec-cost.eu/our-approach/education-for-environmental-citizenship/

The New School (n.d.). Environmental Citizenship. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.nuevaschool.org/about/notably-nueva/environmental-citizenship

Xiao, B.; Girand, C., & Oviatt, S. (2002, September). Multimodal integration patterns in children [Conference presentation]. 7th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, Denver, Colorado, United States.