| Reading Risky Texts – Using a Guided Reading Approach to Introduce Interculturality and Ideology in India

Jennifer Thomas, Anandita Rao and Sujata Noronha |

Download PDF |

Abstract

Reading a risky text with adolescents within the context of a school poses many challenges. This essay describes how the pedagogy of guided reading and the notions of critical literacy and multimodality were used to foster deeper understanding of interculturality and critical thinking about ideology among a group of 11 to 15-year-old Indian students using Markus Zusak’s novel The Book Thief during the pandemic years of 2020-21. The text was risky for the target group because of the themes of death and loss that abounded at the time in India in the midst of the second wave of the global pandemic. It was also risky because The Book Thief, with complex themes around ideological control and persecution, asks readers to negotiate a potentially diverse range of complicated thoughts that the educators (present authors) desired to open up against the landscape of Indian politics. Intercultural texts of this kind remain marginal in the Indian school curriculum. In discussing why this text was chosen, and describing activities that were designed to enable multimodal learning, the article provides a framework for guided reading explorations of other risky texts that can promote an understanding of interculturality and ideology among students in meaningful ways.

Keywords: guided reading, risky texts, interculturality, language learning

Jennifer Thomas is an educator who leads the library programme at Sharon English High School, Mumbai. Jennifer’s research focuses on aspects of how children learn English in an ESL context. More recently Jennifer has been exploring how the library can support diverse learners to become readers.

Anandita Rao is a Library Educator at Bookworm, a library-based organization in Goa, India. Anandita works closely with the library collection which shapes her continued understanding of children’s books and literature, and has the privilege of working on library practice with different communities in Goa.

Sujata Noronha is an educator and the Founder Director of Bookworm – a library-based organization in Goa, India. Sujata’s research focuses on how to decolonize library practices to make libraries more inclusive especially for diverse communities entering into formal literacy in India.

Introduction – Background to the Project

Literature allows educators to move beyond literacy basics, or functional literacy, and towards an expanded vision of literacy where readers not only understand what they are reading but also come to see its relevance to their lives and are able to ‘use, critique and navigate’ written worlds effectively (Menon, 2018). Unfortunately, literature of this kind, ‘remains marginal in school libraries, in reading lists and in teachers’ planning, in L1 and L2 contexts’ (Dolan, 2014, p. 107). It is no different in Indian schools, where reading literature is not privileged, library collections are limited and literature in various forms are included only in ‘textbooks’ that are often rigidly prescribed by the state. The Indian scholar Krishna Kumar writes, ‘In the ordinary Indian school, the textbook dominates the curriculum. The teacher is bound by the textbook since it is prescribed, and not just recommended by state authorities’ (Kumar, 1986, p. 1309). When students aged between 11 and 15 years concluded a presentation based on the guided reading workshop that Bookworm Library (Goa) had conducted for students of Sharon School (Mumbai) on Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief, a school leader communicated the following:

A thing that amazed me was the book you selected and the topic which the book dealt with. Everywhere, I could hear about death. We always try to shy away from death. It was lovely that you took this theme up and engaged with the negative emotions and the negative characters in this story. It was so nice to see the students opening up and sharing about this. (A. Thomas, personal communication, June 9, 2021)

The sessions were conceptualized and conducted by a team of three library educators from Bookworm, a library-based organization in Goa, India, with a vision to inspire and develop a love for reading as a way of life, nurturing humane engagement in everyone. Through Bookworm’s community and school engagements, there is a conscious objective of creating a safe space for dialogue around themes that are often resisted or challenged in society. As a means of nurturing more humane views and ways of interaction, the focus of library sessions is located within texts that provide the opportunity to experience books as both mirrors of one’s own experience and windows (Bishop, 1990).

Sharon School is a neighbourhood school in the city of Mumbai, Maharashtra, India with classes from grades 1 to 10. Students come from multilingual backgrounds where English is not the first or second language. However, the medium of instruction in the school is English and three Indian languages are also taught. Though it is not a state-funded school, it is regulated by the rules of the state education department and therefore follows the state board curriculum. The academic implication of this regulation is that the school is bound to follow the state-prescribed syllabus. India has a strong textbook culture (Kumar, 1986) where teachers rarely deflect from or augment the syllabus with other resources. For the past few years, however, the school has taken efforts to infuse a love of reading through the school library. A new space for the library was created just one year before the global pandemic with professional development and mentoring support from Bookworm. This allowed students open access to books. During the pandemic months, when schools remained closed, city laws allowed the school to reopen the library and it slowly emerged as a bridge between the school and the student community.

The workshop presented an experience of a text offering intercultural opportunities for students in an Indian school, to not only think about the story – historical fiction with themes of death and loss – but also about political ideologies and how they play out in everyday homes. A related objective was to also explore and strengthen ELT practices within a context where English is not the first language but is the language of instruction, in the hope that it would foster language learning and critical reading skills among students. This essay describes how the pedagogy of guided reading, interculturality, critical literacy and multimodal learning shaped the design and delivery of sessions, while also examining how students responded to these sessions.

The Guided Reading Workshop

The reading intervention was organized as a guided reading workshop (https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/readingviewing/Pages/teachingpracguided.aspx). This was offered as an online, vacation workshop between May and June 2021 and could be largely located within the space of the library efforts at the school. The participant group who signed up for this workshop included 20 students in the age group of 11 to 15 years. It was designed and delivered as a five-week-long workshop where students met with the library educators from Bookworm once a week for two hours and additionally on a Sunday for a voluntary reading circle. All interactions between participants and facilitators were in English. A multimodal approach to response was critical in planning the sessions as it would be offered online and pre-adolescent students, with unknown reading fluency and limited access to resources, were likely to enrol in the workshop.

We define library educators as educators who work and facilitate library-based programmes but who adopt a dialogic stance as compared to teachers, who are more directive and tend to often be looked upon as ‘the sage on stage’. This workshop was conceptualized and led by library educators from Bookworm and two library educators from Sharon School apprenticed to the workshop through regular participation and observation.

This project unfolded against a complex sociopolitical landscape in India – school closure due to forced lockdowns, rising nationalism, protests for citizenship by marginalized communities in India, economic downswings, advanced technologies being deployed for profit, election manipulation, fascist ideas rising, climate change and a devastating pandemic affecting everyone, rich and poor, in the country. It was in these ‘dark’ times and a suggestion from the school library educator to demonstrate engagement with a risky story (Damico, 2012) that led to reflecting and selecting The Book Thief by Markus Zusak.

The reasons for selecting the text were both multiple and specific, including:

- Theme of the story in close alignment with power of literature and act of reading,

- The context of the story as a window and mirror on parts of contemporary India,

- The treatment of story in the book, which lent itself to multimodal exploration,

- The opportunity to challenge the students to read above their ‘level’ in a guided reading workshop.

The next section discusses the theoretical framework that informed the design of the workshop and how interculturality was explored through a literary text like The Book Thief.

Theoretical Framework

Risky texts are said to refer to stories that deal with difficult social issues, which, according to context, may be lacking in the curriculum of particular subjects and are therefore not typically explored in elementary or secondary school classrooms (Damico, 2012). They are risky because they can pose psychological and emotional risks for readers as they are called to negotiate complicated thoughts and feelings ranging from despair to shame and anger to hostility (Robertson, 1997). These feelings emerge from immersion in the storyworld by reading (fictionalized) survival accounts and could stem from complexities of empathizing with characters in the story. Reading about issues like enslavement, discrimination, genocide of indigenous people and the Holocaust can help students learn the historical significance of these events, enabling them to make connections with their own lives and the injustices in the contemporary world. In the Indian school system, with a strong textbook culture, students are not exposed to risky stories of this nature. Secondly, the term also signals challenges a teacher facilitating such a text may face or experience when called upon to listen, understand and respond to potentially complicated responses from students. Risky stories, however, also present fertile ground for inquiry-based learning and critical literacy practices, where literature can enable readers to explore four dimensions – disrupting the commonplace; interrogating multiple perspectives; focusing on sociopolitical issues, and taking action and promoting social justice (Lewinson et al., 2002). The guided reading approach presented a robust framework to open up and engage students with texts of this nature.

The guided reading pedagogy was explored to support the reading of The Book Thief, a text that was risky in the Indian context and above the reading level of the group and therefore needed scaffolding. In this approach students have the opportunity to talk, think and read their way through a text in the company of more proficient readers (adults) (Department of Education, Victoria, 1997). This approach is different from traditional reading pedagogy, which involves instruction and checking comprehension through questions, but is often criticized for not promoting an aesthetic or critical reading of literature (Bland, 2018; Short, 2022). Guided reading is informed by Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development and Bruner’s (1986) notion of scaffolding learning, which helps develop greater control over the reading process through the development of reading strategies that assist decoding and construction of meaning. It is an interactive process. Strategies involve, but are not limited to, frontloading new vocabulary, highlighting language structures or literary devices such as symbolism and foreshadowing while also promoting different levels of comprehension (literal, inferential, evaluative). The teacher guides or ‘scaffolds’ students as they read and gradually withdraws support once the strategies have been practised and internalized.

Both Bruner (1986, 1990) and Geertz (1973) held that human beings are culture makers and in participating in culture they complete themselves. Culture is therefore the water all humans swim in and it is in its confluence with other waters (other cultural groups) that one’s own understanding expands. Cultural windows and mirrors are now well accepted metaphors for using literature with students and this formed the basis of exploration with a text in the guided reading workshop. Geertz (1973) defines culture as ‘the shared patterns that set the tone, character and quality of people’s lives’ (p. 216). Bruner (1990) argued that the aim of meaning making was to discover and to describe formally the meanings that human beings created out of their encounters with the world, and then to propose hypotheses about what meaning-making processes were implicated.

The time period of being locked down during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, afforded the opportunity to expand opportunities for interculturality by reading a ‘window’ text (one that is set in the time period of World War II and in a faraway country – Germany). Moreover, it is also a ‘mirror’ text (one that we argue reflects the ideology of the ‘Hindu nation’ and cultural hegemony formation in India, a time of heightened state control and restrictions imposed by the pandemic). This compelled participants and authors of this paper to form a thought collective (Fleck, 1933, see https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/fleck/).

It is in this way that the guided reading workshop became a strategic act towards interculturality rooted in exploring ideology. Interculturality is one way in which respectful interaction between people from different cultural backgrounds can be promoted. In the absence of direct interaction, the text allowed students to enter another cultural context through the storyworld of the characters. While interculturality typically enables integration, solidarity and coexistence between individuals (Gabriela, 2019), this guided reading experience also enabled students to draw parallels between the storyworld and their lived experience of the global pandemic, and interrogate their present cultural context to some extent.

Working with The Book Thief (2006)

The Book Thief is organized in a way that provides an attractive entry point to students of varying fluency. This text was at a higher reading level than what the students usually encountered in the school curriculum. A dialogic pedagogy was thus central to the session design, to open up safe spaces to begin some much-needed conversations on the language of the text as well as the ideas presented therein. The educators wished for students to go beyond the phoneme and grapheme level of the text and see reading literature as a social practice, as having ‘grand conversations’ about social issues that are important in present times (Peterson & Eeds, 2007). The next step involved brainstorming ideas on what would constitute evidence for these results. The multimodal literacies framework enabled educators to design a variety of artifacts (as shown in Table 1) that students could create to reflect their learning. Finally, detailed learning plans were drawn up on a session-by-session basis using the backward design approach (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Students’ responses and reading pace informed the design of subsequent sessions. This iterative design process enabled educators to keep reflecting on what social practices instituted around discussion of the text was effective and how reading could be made more effective for students at varying levels of comprehension, pace and interest.

| Journal Making | Each participant stitched together their own journal that was sustained throughout the course of the workshop, and provided an anchor for many as the text itself increased in weight and thought. This idea was inspired by the books created for Liesel Meminger by Max Vandenberg in the story. |

| A Timeline | The Book Thief consists of 10 parts, in addition to the prologue and epilogue. For each part that was read, each student chose four key events that captured that part for them, and created their own accordion timeline that was added to from time to time. This idea was drawn from Hans Hubermann’s accordion playing in the novel. |

| Character Analysis | Character descriptions that were built on, and further shaped after every new reading. |

| Cover Page Art | The cover page of the journal was worked on last. In following Max’s book creation in the story, where he paints over Mein Kampf with white paint, each participant chose a newspaper article that evoked negative feelings for them. They painted over words or left others unpainted to depict ideas they would like to resist like religious intolerance, hate crimes and inequality. |

| Sentence Identification | Sentences from each part that was read that struck someone were gathered together because of what those sentences evoked.

Students were also encouraged to draw images that came to mind based on certain evocative sentences. |

| Book Covers | Book covers were designed by the students based on descriptions of other books stolen by Liesel Meminger within this story, which prompted students to visualize and recreate cover images. |

| Summaries and Presentations | Individually, each participant chose chapters to read and present back to the group, as a process of making sense of what was read and sharing back. |

| Sky Paintings | Inspired by Liesel’s description of the sky to Max, who could not see the sky as he was hiding in the basement, the students created paintings based on evocative descriptions of the sky by other students. |

| Creating Poetry | Inspired by Charles Causley’s (2000) poem ‘I am the Song’ (p. 386), students created their own poem based on what stayed with them at the end of the guided reading workshop. |

Table 1. Activities facilitated as part of the guided reading process

Most students in Indian classrooms have encountered ideas on World War II as short paragraphs within social studies curricula. The Book Thief assumes a much wider knowledge of the sociopolitical situation in Germany at the time. This was presented in the form of a brief pre-story about the rise of the National Socialist Party (NSDAP) in Germany, the making of Adolf Hitler, economic and political context and the relationship of Germany with ‘Allied’ countries. When the students encountered the political leanings of Liesel’s family vis-à-vis the ruling German party, the background knowledge helped them understand why Liesel’s mother would send her away to live with a foster German family. As the sessions unfolded, students also participated in a read-aloud of picturebooks such as The Lily Cupboard by Shulamith Levey Oppenheim, The Butterfly by Patricia Polacco, and Rose Blanche by Christophe Gallaz, illustrated by Roberto Innocenti, which provoked them to ask questions about why Jews were fleeing and hiding. It was this background knowledge about the economic, political and ideological position that helped the students understand the danger of hiding a Jew in the basement. These conversations also allowed the group to reflect on the political and ideological positions emerging in India, especially about ‘purity’ ‘race’ and ‘religion’.

Interculturality cannot be explored in the absence of perspective-taking. The role of Death as the narrator in The Book Thief lent itself perfectly to this. There is Death as a witness, as an internal character, as a conversant with the reader, and as a narrator of Liesel’s story. The use of this craft of writing enabled the students to ‘read’ from different points of view and get at least a 180-degree reading of the situation. Death was for the first time a beloved character for the group and it was affirming to note how from tentative talk about death as absence, death became alive in conversations. This was in some ways a balm to all the students in the group as many students and adults had experienced news and fear about death around the pandemic. Hinton et al. (2014) wrote that contextualization is crucial ‘How and why individuals acted as they did is tied to what was going on in the world around them – that cannot be separated. Knowing and understanding that context and the chronology of that context allows the reader to have a true understanding of the characters in the novel’ (pp. 22-27).

At the beginning of the workshop, each participant chose one character, and followed that character through the story, building and shaping their own understanding of this character, as more facts, and experiences emerged from the text. This seemingly simple activity strengthened empathetic reading, perspective-taking and understanding as students began to predict responses and outcomes based on how deeply they had internalized and understood the condition of the chosen character. When Rudy dies in the book, it was not just tragic for the students who had selected Rudy but also for Rudy’s friends like Liesel and the Hubermans who knew Rudy as a boy. Many students were dismayed that he died but all of them understood that the plot and period had to provide victims and the story must go on.

Analysis

Each session was planned to encourage active participation in different modes – reading, watching, talking, playing, painting and writing. Language is first and foremost a social meaning-making process, best learnt in the presence of others. Coming together, communicating and sharing thoughts and feelings became crucial as the sessions unfolded. The educators created a safe space for all, using simple strategies: students addressed everyone, including the educators, by their name, there was careful listening to each other’s questions and comments, an additional reading circle was opened up on Sundays for those who wanted to read the text together.

Among the participants, there were those who listened and those who talked, those who used the chat box to chat privately with educators or with the group, and those who engaged through materials that they brought and showed. There was a space for everyone’s voice that was created, the quieter ones through chat/private chat, the confident ones through raised hands and voicing out. And there was the space for different paces, times for quiet reflection, times of intense discussion, and times of high energy games. Typically, in our context, teachers often need to be fully present and in control of discussions while interacting with a group of individuals. But as library educators, the facilitators adopted a dialogic stance to create an environment of mutual trust and sharing. In the online mode, students were encouraged to go into Zoom breakout rooms, independently work on short tasks, and collaborate to present in-depth responses. Trusting the students to explore content together ensured that the interaction was not always teacher-led, it emphasized the spirit of collaboration and sharing. In the later sessions, students also created artifacts (art, multimedia presentations) that reflected their voices and thoughts.

The texts employed in this unit for intercultural learning served as windows and mirrors (Bishop, 1990) for different readers at different times. One of the early dialogues The Book Thief opened up was on the issue of smoking cigarettes and Liesel rolling cigarettes for her foster father, Hans. Students asked ‘Doesn’t that make Hans a bad man? Why is Liesel in his house? Will she be safe?’ The book provided many opportunities like this for students’ moral reasoning to develop and research shows that this ability improves in students when they work through ethical dilemmas in literature. In deferring a moral judgment on smoking and attempting to understand it through a discussion about the period the book is set in, the weather in that context, the understanding of society about smoking – the aspect of interculturality across time become clear to the students; the dialogue that unfolded indicated to students that they could ask risky questions and they would not be judged. In fact, they were likely to get more information and make more connections.

Many aspects, like locating the text historically, looking at the larger geopolitical context of the times through multimodal presentations, audio visuals and picturebooks about the time, place and period invited students into the learning experience with literature. As they read, students began noticing differences in physical features of Max, a Jew and how the colour of their hair and eyes was used to profile the Jewish community under the Nazi regime. Understanding such aspects of race through the Holocaust experience enabled the students to begin to grasp ideas of racial prejudice and the dangers of stereotyping. Activities like finding a newspaper article which evoked negative emotions in them, painting over it (like Max in the story) and using it to cover their journals further urged them to draw parallels with the present regime in India, thereby compelling them to think more carefully about ideology and power. This impact is captured well in a comment by a reader:

In just a month I feel like I went to Germany, during 1933, the time of Hitler’s dominance. The novel selected by the team is so wonderful that it made me sentimental. Each event, each character in the book felt so heartwarming. A message I learnt during Reading with Bookworm these sessions (sic) that I would love to share is ‘If your heart feels something is wrong, oppose it!’ A warm ‘thank you!’ to the Bookworm team. Their efforts have somewhere broadened our thoughts. (Gala & Joshi, 2021)

The guided reading approach was specifically adopted as an approach to scaffold students who were reading at a higher grade level than they usually did. In addition to the safe spaces for dialogue, the language scaffolds too were crucial in ensuring comprehension, which eventually led to expression in multimodal ways. Vocabulary games highlighted linguistic aspects that would otherwise have gone unnoticed. While these games gave students opportunities to practice basic skills of spelling and expression of meaning, the journal making, timeline creation and character mapping gave them opportunities to put this vocabulary into use and play with language in new ways.

The aesthetic role of language was made visible through a simple painting activity (see Figure 1) in one of the online sessions. Max Vandenberg is a Jew in hiding in The Book Thief who can only occasionally see the sky, which prompts Liesel to describe the sky to him in words that Max visualizes and illustrates. Inspired by Max’s questions on the sky, each participant observed the sky outside their window and represented it on paper using different art supplies. It is heartening to note how the memory of an aesthetic stance of reading (Rosenblatt, 1976) continues to stay with the students as demonstrated in a recent comment by one of the participants from this group, a whole year later, to his classmates during library hour. In eliciting the features of the horror genre, the theme of death came up in the classroom discussion. The participant took the floor towards the end of the session and recommended that if anyone wants to know more about death, they must read The Book Thief where Death thinks in colours and describes many things, so beautifully and with so many emotions. This is a striking intertextual connection affirming the positive role of multimodal activities.

Figure 1. Sky paintings that students created based on evocative descriptions of the sky by other students

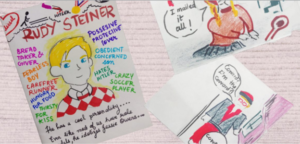

Initially, students struggled with summarizing a chapter clearly and concisely, often re-telling it to the last detail. As sessions progressed, students gradually began to identify key events, highlight conflicts and share their reflections in comprehensive summaries. The timeline and journal entries they maintained (see Figure 2), further helped them hone these summarizing skills with care and attention. The character map of Rudy as represented by a student (Figure 3) demonstrates that students were reading with understanding, they were making inferences and were also able to synthesize information appropriately.

Figure 2. Journal entries

Figure 3. Character Map

Following one character’s story also helped participants engage with the plot at a deeper level and this engagement was demonstrated in the character maps they drew as well as the thought-provoking questions they posed each other in the final game of hot-seating that was played. This is a post-reading conversational game where readers assume a character identity and respond in role to questions posed to their character revolving around the plot, events and feelings. In a culminating session, a character reveal was organized, where each participant came dressed as or brought along with them something that encompassed their character in some way. As each character emerged through a spotlighted video, everyone guessed the character, and asked thoughtful, playful and thought-provoking questions to the character personas, such as:

‘Did you miss your family, Max?’

‘What made you like stealing books, Liesel?’

How did it feel to be alone in the basement, Max?’

‘Why did you scold (everyone) so much, Rosa?’

‘How does it feel when you take someone’s soul, Death?’

Weeks of being immersed into the thoughts, feelings and experiences of each individual in the story, provoked a genuine manifestation of each character, as readers had walked through their lives in so many ways now. Death was a favourite among many, and it was interesting to explore and imagine what Death looked like as Zusak keeps this as a mystery throughout the book.

None of this would have been possible without the dialogic, humanizing stance that the educators adopted. In the banking model of education, the teacher presents reality as something static, compartmentalized and predictable. There is extreme polarity in the teacher to student relationship where the teacher considers themself to be superior and is seen to bestow the learner with the gift of knowledge. Projecting such absolute ignorance onto others is a characteristic of the ideology of oppression as it seeks to maintain the status quo in society (Freire, 1970/2000). The banking model of education is built on the idea of a submersion of consciousness where reality is anesthetized, and creative power is inhibited. Freire outlined another model of education that he called problem-posing education, which supports an emergence of consciousness among learners through a critical intervention of reality. This guided reading experience demonstrated how a facilitator could bring the world closer to students through the ‘word’ and help them examine that the ‘world’ is not static but a reality in process and in transformation through discussions on ideology and power. Importantly, culture is also not static, compartmentalized or predictable.

Conclusion

This paper highlights the affordances of a guided reading approach to reading a text with opportunities for interculturality with a group of students with diverse abilities. This approach supported the educators to design for and explore twin objectives of language learning and interculturality. Though English was not the first language of the students, the session framework and the dialogic stance of the educators helped the students to comprehend the text, make intercultural connections and think critically about the world around them. Ghosn (2013, p. 46) suggests that, ‘vicarious story experiences, if frequent and intense enough, might shape brain circuits for empathy, leading the reader to identify and empathize with an ever-widening circle of people’. These were some of the big affordances of the guided reading approach that the library educators experienced to varying degrees with this group of learners.

In this process the library educators learnt a few things that could be considered as guidelines for similar workshops. It is important to know the students, provide them with a choice (in this case to attend or not) and trust that children can engage with complex ideas and emotions. It would be helpful to assess the larger world around the student to ensure one picks a text that they can relate to. It would also be helpful to get a sense of their reading history and language levels and skills before choosing the text. It is important to find a text or an ensemble of texts that will trigger and enable multimodal pathways of reading response. If the facilitator/educator loves the selected text(s), it only makes the experience of reading in a community more enriching. It is critical to devote time to planning, reflecting and reviewing whilst the process is ongoing. Most importantly, trust the students’ responses to direct the next steps, interact with other colleagues who work with the students, and have fun.

What stayed with the young students from the text, what did they carry away with them and did it help them find some solace in this fractured world that they inhabit? Some answers can be found in the poem that the students composed at the end of the workshop, inspired by Charles Causley’s poem (2000) ‘I am the Song’ (p. 386)

I am the day that began your birth

I am the heart that lives in death

I am the hope that warms the sun

I am the stories that students met

I am the book that calls the thief

I am the shiver that chills the snow

I am the apple that grows the leaf

I am the chimes for the wind to blow

I am the music that plays the man

I am the land that caught the bombs

I am the pages that turn the hand

Bibliography

Causley, Charles (2000). I am the Song. In Paul Cookson (Ed.), The Works (p. 386). Macmillan Publishers Limited.

Gallaz, Christophe, illus. Roberti Innocenti (1985). Rose Blanche. Creative Editions.

Oppenheim, Shulamith Levey, illus. R. Himler (1992). The Lily Cupboard. HarperCollins Publishers.

Polacco, Patricia (2000). The Butterfly. Philomel Books.

Zusak, Markus (2006). The Book Thief. Alfred A. Knopf.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6(3), ix–xi.

Bland, J. (2018). Popular culture head on: Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games. In J. Bland (Ed.), Using Literature in English Language Education: Challenging Reading for 8–18 Year Olds (pp. 175-192). Bloomsbury.

Bruner J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press.

Damico, J. S. (2012). Reading with and against a risky story: How a young reader helps enrich our understanding of critical literacy. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 6(1), 4-17.

Department of Education, Victoria (1997). Teaching readers in the early years. Addison Wesley Longman Australia.

Dolan, A. M. (2014). Intercultural education, picture books and refugees: Approaches for language teachers. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 2(1), 92-109. https://clelejournal.org/intercultural_education_picturebooks_and_refugees/

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum. (Original work published 1970)

Gabriela, B. V. (2019). Interculturality. De Euston96. Retrieved May 14, 2022, from https://www.euston96.com/en/interculturality/

Gala, R., & Joshi, J. (2021, June 24). Guided reading with bookworm. Sharon English School. http://sharonschool.in/reading-with-bookworm/

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. Basic Books.

Ghosn, I. K. (2013). Humanizing teaching English to young learners with student’s literature. Children’s Literature in English Language Education 1(1), 39-57.

Hinton, K., Yonghee, S., Colón-Brown, L., & O’Hearn, M. (2014). Historical fiction in English and social studies classrooms: Is it a natural marriage? English Journal, 103(3), 22-27.

Kumar, K. (1986). Textbooks and educational culture. Economic and Political Weekly, 21(30), 1309-1311. https://www.epw.in/journal/1986/30/perspectives/textbooks-and-educational-culture.html

Lewinson, M., Flint, A.S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382-392

Menon, S. (2018). Supporting early language and literacy through students’ literature. http://eli.tiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/BhashaBoli_English.pdf

Robertson, J. P. (1997). Teaching about worlds of hurt through encounters with literature: Reflections on pedagogy. Language Arts, 74(6), 457-466

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1976). Literature as exploration. Noble & Noble.

Peterson, R. and Eeds, M. (2007). Grand conversations: Literature groups in action (Rev. ed.). Scholastic.

Short, K. (2022). Foreword, story as life-changing learning. In J. Bland, Compelling stories for English language learners: Creativity, interculturality and critical literacy (pp. 12-14). Bloomsbury.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wiggins, Grant & McTighe, Jay. (2005). Backward design. In G. Wiggins & J. McTighe (Eds.), Understanding by design (2nd ed., pp. 13-34). ASCD.